Abstract

The process of associating items encountered over time and across variable time delays is fundamental for creating memories in daily life, such as for stories and episodes. Forming associative memory for temporally discontiguous items involves medial temporal lobe structures and additional neocortical processing regions, including prefrontal cortex, parietal lobe, and lateral occipital regions. However, most prior memory studies, using concurrently presented stimuli, have failed to examine the temporal aspect of successful associative memory formation to identify when activity in these brain regions is predictive of associative memory formation. In the current study, functional MRI data were acquired while subjects were shown pairs of sequentially presented visual images with a fixed interitem delay within pairs. This design allowed the entire time course of the trial to be analyzed, starting from onset of the first item, across the 5.5-s delay period, and through offset of the second item. Subjects then completed a postscan recognition test for the items and associations they encoded during the scan and their confidence for each. After controlling for item-memory strength, we isolated brain regions selectively involved in associative encoding. Consistent with prior findings, increased regional activity predicting subsequent associative memory success was found in anterior medial temporal lobe regions of left perirhinal and entorhinal cortices and in left prefrontal cortex and lateral occipital regions. The temporal separation within each pair, however, allowed extension of these findings by isolating the timing of regional involvement, showing that increased response in these regions occurs during binding but not during maintenance.

Keywords: functional magnetic resonance imaging, human, perirhinal, lateral occipital, encoding

when navigating through the world, people encounter a stream of information. Items that are deemed important will be attended to, and associations will be made between these related items to create more robust memory for the event. What factors predict which associated items will be later remembered? Prior studies using concurrently presented stimuli focused mainly on which regions are involved in forming associations. This approach, however, represents a very limited view of associative memory formation in the real world and misses an important aspect of encoding the stream of information one encounters. Thus recent studies have delved more deeply into associative memory formation to examine how items are linked and encoded across a delay (Hales and Brewer 2010; Hales et al. 2009; Konkel et al. 2008; Murray and Ranganath 2007; Qin et al. 2007, 2009; Sommer et al. 2005a,b; Staresina and Davachi 2009; Takeda et al. 2005). These studies have reported the involvement of medial temporal lobe (MTL) structures as well as additional neocortical regions, including prefrontal cortex (PFC), medial frontal cortex, parietal cortex, and lateral occipital/inferior temporal regions in forming associative memories for temporally discontiguous items. To address how regions cooperate in and contribute to forming these memories, investigation of the time course of activity across the entire encoding event is essential; in humans, however, examination of these temporal components has only recently gained attention.

Beyond these questions regarding the timing of regional contribution to memory formation, fundamental disagreement remains about the specific involvement of MTL substructures in associative memory formation. Although several neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies have reported the involvement of the parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) in associative memory encoding (Chua et al. 2007; Davachi et al. 2003; Davachi and Wagner 2002; Eichenbaum et al. 2007; Gold et al. 2006; Hales and Brewer 2010; Hales et al. 2009; Kirwan and Stark 2004; Murray and Ranganath 2007; Pihlajamaki et al. 2003; Qin et al. 2007, 2009; Staresina and Davachi 2010; Taylor et al. 2006; Tendolkar et al. 2007), studies have suggested functional distinctions between PHG substructures based on associative versus item encoding (Achim and Lepage 2005; Aminoff et al. 2007; Davachi 2006; Peters et al. 2007; Sommer et al. 2005a; Staresina and Davachi 2008, 2009), novel object perception versus spatial processing (Pihlajamaki et al. 2003), encoding versus retrieval process (Daselaar et al. 2006), and context-dependent learning versus explicit recognition memory (Preston and Gabrieli 2008). These results support the separable contribution of particular MTL substructures to different aspects of memory encoding and retrieval.

Many neuroimaging studies have reported that anterior regions of the MTL, such as perirhinal cortex (PRC), entorhinal cortex (ERC), anterior parahippocampal cortex (PHC), and anterior hippocampus, are involved in the formation of associative memories (Aminoff et al. 2007; Chua et al. 2007; Jackson and Schacter 2004; Mayes et al. 2007; Peters et al. 2007; Pihlajamaki et al. 2003; Rauchs et al. 2008; Sperling et al. 2003; Staresina and Davachi 2006, 2009, 2010; Taylor et al. 2006), whereas more posterior regions of the PHC and hippocampus are involved in visual item memory (Kirchhoff et al. 2000; Peters et al. 2007; Rauchs et al. 2008). Such findings, however, are not universal. Some studies have suggested that the locus for associative memory formation is the hippocampus, whereas item memory formation preferentially involves PRC (Chua et al. 2007; Diana et al. 2007; Eichenbaum et al. 2007; Staresina and Davachi 2009).

Recently, studies have started addressing this discrepancy by looking more closely at the specific types of associations being made. In a recent review, Mayes et al. (2007) provided support for PRC involvement in within-domain associative encoding and hippocampal involvement in between-domain associative encoding based on human psychological and functional imaging studies as well as human and animal lesion studies. Additional studies have also supported this distinction in PRC and hippocampal contribution to associative encoding, where PRC is involved in forming associations that are unitized or regarding item-related details (such as item-color associations) and the hippocampus is involved in forming domain-general or item-context associations (Diana et al. 2007; Staresina and Davachi 2008, 2010).

Extensive anatomical research of the cortical projections to MTL substructures also supports a functional dissociation within PHG. Tracing studies in the macaque monkey have indicated that PRC receives cortical inputs that are distinct from inputs to PHC (Suzuki and Amaral 1994). ERC receives the majority of its inputs from PRC and PHC but also receives projections from additional neocortical regions, including superior temporal gyrus and orbitofrontal cortex. Similar results have been reported using retrograde tracing in the rat, where PRC and postrhinal cortex each receive distinct cortical and subcortical inputs (Furtak et al. 2007). The anatomical evidence of distinct cortical inputs to PRC and PHC suggests and supports functional differences between anterior and posterior regions of the PHG.

Results from electrophysiological studies in monkeys provide further support for involvement of anterior parahippocampal regions, such as PRC and ERC, in associative memory. Neurons in inferotemporal cortex showed “associative” responses, while monkeys performed a visual paired-associates task (Higuchi and Miyashita 1996; Sakai and Miyashita 1991). In these studies, neurons were identified as “pair coding” if, after training, they showed a preferential response to a stimulus and to its associated pair. Neurons were identified as “pair recall” if, having shown a strong response to a stimulus, the neuron also fired strongly in the period following the presentation of the pair of the stimulus. These responses were identified only in monkeys with an intact entorhinal and perirhinal region. Although anterior PHG lesions ablated the associative memory responses, they did not diminish neuronal responses to individual stimuli (Higuchi and Miyashita 1996).

Electrophysiological studies in monkeys have also examined delay period activity in PFC and MTL regions during associative encoding of temporally discontiguous stimuli. Fuster et al. (2000) recorded extracellularly from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) while monkeys performed a sound-color associative encoding task. They reported that cells in DLPFC exhibited correlated firing for associated colors and tones and that some of these cells also showed increased firing during the delay between tones and their associated colors (Deco et al. 2005; Fuster et al. 2000). Electrophysiological results in rats and monkeys are inconsistent, however, regarding MTL activity during short-delay maintenance. Some studies have reported MTL activity during short-delay maintenance (Cahusac et al. 1989; Watanabe and Niki 1985; Young et al. 1997), whereas others have reported very rare or no MTL activity during the delay period (Hampson and Deadwyler 2003; Vidyasagar et al. 1991). Human lesion and imaging studies looking at working memory also report mixed results of MTL involvement in delay period maintenance (Axmacher et al. 2007; Cave and Squire 1992; Ezzyat and Olson 2008; Grady et al. 1998; Habeck et al. 2005; Hannula et al. 2006; Hartley et al. 2007; Kessler and Kiefer 2005; Monk et al. 2002; Nichols et al. 2006; Olson et al. 2006a; Petit et al. 1998; Picchioni et al. 2007; Piekema et al. 2006; Ranganath et al. 2004; Ranganath and D'Esposito 2001; Shrager et al. 2008; Stern et al. 2001). Although delay period activity has been examined in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of working memory, the few studies that have looked at associative encoding of temporally discontiguous stimuli have focused on subsequent memory effects during the encoding of the items (Hales and Brewer 2010; Hales et al. 2009; Konkel et al. 2008; Murray and Ranganath 2007; Qin et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2009; Sommer et al. 2005a,b; Staresina and Davachi 2009; Takeda et al. 2005). One exception is a study that examined associative and item encoding of temporally discontiguous stimuli, which showed increased PFC activity during the delay between paired items relative to the delay between unpaired items (Hales et al. 2009). This study, however, only examined successfully encoded paired and unpaired items; therefore, intrapair delay period activity has yet to be explored in relation to subsequent associative memory.

The current study examines the time course of activity across the entire associative encoding event of two temporally discontiguous items. MTL and PFC activity during this associative encoding task were examined using rapid event-related fMRI, and the subsequent associative and item memory for the visual stimuli were determined using a postscan recognition test. By presenting each item individually and controlling for item memory strength, brain activity in response to successful associative binding could be isolated. Based on previous findings, the prediction was that anterior MTL regions, such as PRC, ERC, and anterior hippocampus, and PFC regions would show increased activity for successful associative binding. In addition, subsequent associative memory effects were predicted to occur in frontal regions during both maintenance (following presentation of the first item of the pair) and binding (once the second item of the pair was presented); however, subsequent associative memory effects were predicted to occur in anterior MTL regions only during binding with no difference during maintenance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Fifteen healthy volunteers (mean age 26.6 ± 3 yr, 7 males) were recruited from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) community and the surrounding area. All subjects gave informed consent approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board and had normal or corrected vision.

Stimuli.

Two hundred ninety color images of everyday objects were used as stimuli in this experiment. While subjects were in the scanner, 250 of the images were presented sequentially; a plus sign was presented during the interitem delay to link each set of two images and reduce cross-pair binding. During the postscan recognition test for item memory, the remaining 40 stimuli were included as foils. Images were acquired from Rossion and Pourtois color Snodgrass images (Rossion and Pourtois 2004) and the Hemera object library (Hemera Technologies).

Experimental procedure.

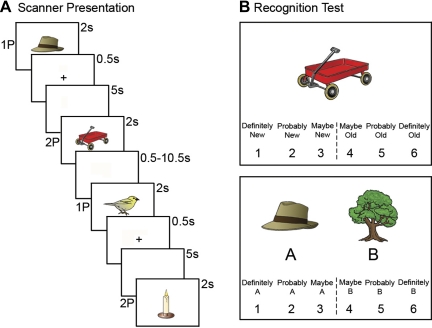

During the associative encoding task in the scanner, subjects were shown pairs of sequentially presented individual images, with each image presented for 2 s (Fig. 1A). All items were paired pseudorandomly to remove obvious semantic relationships between pairs. Between the two images of a pair, a fixed interitem delay of 5.5 s was used with a plus sign presented in the center of the screen for the first 0.5 s of the delay followed by a blank screen for the remaining 5 s. Between pairs were jittered intertrial intervals (ITIs) ranging between 0.5 and 10.5 s. The ITIs were calculated to optimize the study design for modeling the hemodynamic response to trials (Dale 1999; Dale and Buckner 1997). Subjects were told to remember all individual images. Subjects were also instructed to associate the image that preceded the plus sign (1P) with the image that followed the plus sign (2P) and to remember the items as a pair. By separating the 2P item from the instruction to associate (plus sign), this design allowed for isolation of the response to associative binding. Subjects were given a button box and asked to press a left or right button if the image represented a living or nonliving object, respectively, to make sure that subjects were attending to each image. One hundred twenty-five image pairs were presented to subjects in the scanner across five 383-s runs. Each image was presented once, and objects in each pair were unrelated.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. A: example of the encoding task used in the scanner illustrating the sequential presentation of 4 stimuli in pairs of 2 (1P-2P and 1P-2P). Each stimulus was presented for 2 s. After the 1P stimulus, a plus sign cued the association of the preceding stimulus (1P) with the following stimulus (2P). The plus sign was presented for 0.5 s, followed by a 5-s interitem delay. A jittered intertrial interval lasting 0.5–10.5 s separated each 2P stimulus from the next 1P stimulus. B: example of the postscan recognition test. Subjects were shown 2P stimuli previously viewed during the encoding task as well as novel stimuli, and they were asked to rate their confidence that the picture (e.g., wagon) was new or that it was shown during the scan (old) on a scale from “1, definitely new” to “6, definitely old.” If the target stimulus was included in the encoding task, a follow-up question was provided where subjects were shown 2 choice stimuli, A and B (both of which were previously shown during encoding), and were asked to rate their confidence that the target stimulus was paired with image A (e.g., hat) or B (e.g., tree) on a scale from “1, definitely A” to “6, definitely B.”

After the encoding task in the scanner, subjects completed a self-paced postscan recognition test to examine subsequent item and associative memory. Subjects were shown all stimuli previously viewed during the encoding task that followed the plus sign (2Ps) as well as 40 novel stimuli that were used as foils for the item memory question. For each of the 165 stimuli, subjects were asked to rate their confidence that the picture was new or that it was shown during the scan (old) on a “1, definitely new” to “6, definitely old” scale (Fig. 1B). For trials in which the object was previously viewed during encoding, subjects were given an immediate follow-up question in which they were shown two choice images, A and B (both of which were previously shown during encoding), and asked to rate their confidence that the picture was paired with image A or B on a “1, definitely A” to “6, definitely B” scale (Fig. 1B). All 125 2P images from the encoding task were judged in this manner; the 40 novel items were also judged in the same manner, but without a follow-up question. This recognition test lasted ∼30 min.

fMRI parameters.

Subjects were scanned using a 3T GE scanner at the Keck Center for Functional MRI at UCSD. Functional images were acquired using gradient-echo, echo-planar, T2*-weighted pulse sequence (repetition time = 2.5 s; one shot per repetition; echo time = 30; flip angle = 90°; bandwidth = 31.25 MHz). Forty slices covering the brain were obtained perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampus with 4 × 4 × 4-mm voxels. Field maps were acquired to measure and correct for static field inhomogeneities (Smith et al. 2004). A T1-weighted structural scan was acquired in the same plane and with the same voxel size as the functional scans. A high-resolution structural scan was also acquired sagittally using a T1-weighted (1 × 1 × 1-mm) inversion recovery prepared fast spoiled gradient recalled sequence.

Data analysis.

After functional data from each run were field map corrected (Smith et al. 2004), slices were temporally aligned and coregistered using a three-dimensional image alignment algorithm, voxels outside the brain were eliminated using a threshold mask of the functional data, and functional runs were corrected for motion and concatenated, all using the AFNI suite of programs (Cox 1996). A 4.0-mm FWHM Gaussian filter was also applied to smooth the functional data from each run. A general linear model was constructed using multiple regression analysis; six motion regressors obtained from the registration process were included along with eight behavioral regressors based on subsequent memory performance. Subjects' behavioral trials were sorted on the basis of accuracy and subject ratings of item memory confidence and associative memory confidence. On the basis of item memory confidence, trials were divided into four outcomes: high-, medium-, and low-confidence hits (“definitely,” “probably,” or “maybe old”, respectively) and misses (“definitely,” “probably,” or “maybe new,” together). Associative memory was defined as successful (associative) or unsuccessful (item only) on the basis of testing responses. Associative trials were those in which the subject indicated the correct pair with responses of “definitely” or “probably.” Item-only trials were those in which the subject indicated the incorrect pair with responses of “definitely” or “probably” or made any “maybe” judgment. For each outcome, a hemodynamic response function was derived from the fMRI data using signal deconvolution with TENT basis functions and a defined time window of 22.5 s following the onset of each 1P stimulus (Cox 1996). Multiple linear regression analyses were used to examine activity only during the encoding of items that were later remembered with high confidence, with separate measures for when targeted associative information was remembered (associative) or forgotten (item only). These were the only two conditions used for analysis; therefore, all discussions of associative and item-only trials are referring to trials with high-confidence item memory with associative memory or high-confidence item memory without associative memory.

Structural and functional data were transformed into Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux 1998) by AFNI using nearest-neighbor interpolation (Cox 1996) after standard landmarks, including the anterior and posterior commissures, were manually defined on the anatomical scans. Whole brain voxelwise t-tests (2-tailed) carried out across all 15 subjects were conducted to examine which brain regions showed more activity for associative versus item-only memory encoding. Difference during each time period of the event (i.e., 1P, delay, 2P) was examined separately. To correct for multiple comparisons and yield a whole brain significance value of P < 0.01 corrected for all comparisons (based on Monte Carlo simulations), functional clusters of least five contiguous voxels were identified in this condition. The average hemodynamic response function was extracted for each cluster of interest.

To improve MTL alignment between subjects, the region of interest large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping (ROI-LDDMM) alignment technique (Miller et al. 2005) was applied. Bilateral hippocampus and subregions of PHG, including PRC, ERC, and PHC, were defined for each subject on Talairach transformed images. Previously described landmarks were used to define PRC and ERC (Insausti et al. 1998) and PHC (Stark and Okado 2003). These defined anatomical regions of interest for each subject were normalized using ROI-LDDMM to a modified model of a previously created template segmentation (Kirwan et al. 2007). Functional imaging data, after being corrected for spatial distortions with the use of field maps acquired during each subject's scanning session (Smith et al. 2004), underwent the same ROI-LDDMM transformation as was applied to the anatomical data. Active voxels in the associative minus item-only condition, P < 0.05, that were located in the MTL were identified using a mask of the anatomically defined MTL substructures.

RESULTS

Behavioral analysis.

Analyses were focused on trials in which 2P stimuli were recognized with high confidence [61 ± 5% (SE) of all trials]. Of these strongly remembered stimuli, the correct associative pair was identified with medium to high confidence at a rate of 76% (±5% SE; associative condition), and the correct associative pair was not identified or was identified with low confidence at a rate of 24% (±5% SE; item-only condition). Subjects' memory performance was generally accurate, leading to a large number of associative trials, with a mean of 59.9 (±7.3 SE) trials per subject. There were fewer comparison trials in which the subject confidently remembered the item but forgot the association; this item-only condition had a mean of 16.2 (±3.0 SE) trials per subject. Behavioral results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Behavioral results

| Memory Question | Memory Outcome | Percentage of Trials | Average Trials/Subject |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | High confidence | 61 ± 5* | 76.1 ± 6.1 |

| Association | Associative | 76 ± 5† | 59.9 ± 7.3 |

| Item only | 24 ± 5† | 16.2 ± 3.0 |

Values are means ± SE.

Value is a percentage of all trials.

Value is a percentage of high-confidence item trials.

fMRI analysis.

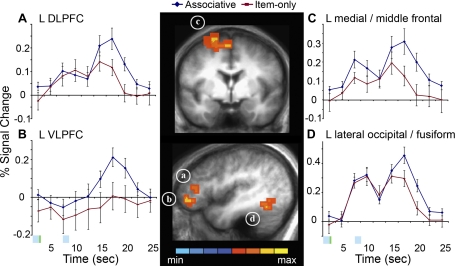

By holding item memory strength constant, brain regions with selective involvement in the successful formation of associative memory could be isolated. These associative memory binding regions were identified where the size of the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response was greater during the encoding of the 2P stimulus when the association was remembered than when it was forgotten (associative minus item-only trials). Regions identified by this contrast (P < 0.01, corrected) are listed in Table 2. Left frontal regions, including DLPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), middle frontal cortex, and medial frontal cortex, as well as left lateral occipital/fusiform cortex, showed increased activity during associative trials relative to item-only trials; this increase was present not during the encoding of the 1P stimulus or during the interitem delay but only once the 2P stimulus was presented and the two items could be associated (Fig. 2, A–D). Left DLPFC, medial/middle frontal cortex, and lateral occipital/fusiform cortex each showed a response to both the 1P and 2P stimulus for the associative and item-only trials, with a larger response to the 2P stimulus only in the associative trials. Left VLPFC, however, only responded to the 2P stimulus during associative trials, with no response during item-only trials. No significant clusters were identified in the reverse contrast during binding (item-only trials > associative trials, P < 0.01, corrected). Associative memory analyses were also performed focusing on the 1P and delay time periods of the encoding event, and there were no regions showing greater activity for associative trials relative to item-only trials during either time period. The only region showing significant subsequent associative memory effects during the delay period was located in right superior temporal gyrus, which showed greater suppression during associative trials relative to item-only trials; no regions showing significant subsequent associative memory effects were identified during the encoding of the 1P item.

Table 2.

Significantly active brain regions for associative vs. item-only trials

| Brain Region | Cluster Volume (mm3) | x | y | z | t Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P < 0.01* | |||||

| Left medial/middle frontal (BA 6) | 1,984 | −18 | −1 | 56 | 4.6394 |

| Left lateral occipital (BA 19) | 1,216 | −46 | −57 | −4 | 4.0167 |

| Left dorsolateral prefrontal (BA 46) | 704 | −38 | 31 | 12 | 4.3769 |

| Left ventrolateral prefrontal (BA 47) | 512 | −42 | 35 | −4 | 4.7694 |

| Right superior parietal/postcentral (BA 7) | 320 | 14 | −45 | 72 | 4.3278 |

| P < 0.05† | |||||

| Left entorhinal cortex | 128 | −17 | −18 | −20 | 2.7346 |

| Left perirhinal cortex | 128 | −25 | 1 | −26 | 2.6658 |

P values indicate significantly active brain regions for associative vs. item-only trials. Coordinates correspond to the voxel of maximum intensity for each cluster (see text).

Values are corrected for multiple comparisons.

Values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons (active voxels for associative vs. item-only trials overlap with anatomically defined medial temporal lobe substructures).

Fig. 2.

Activity in left frontal and lateral occipital regions predicts the successful associative binding of items. Statistical activation maps for regions showing increased activity during binding (P < 0.01, corrected for multiple comparisons) for associative trials compared with item-only trials are overlaid on sagittal and coronal slices of mean anatomical scan images across all 15 subjects. Functional clusters located in left (L) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC; A), ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC; B), medial/middle frontal cortex (C), and lateral occipital/fusiform cortex (D) were used for time-course analyses. Graphs depict the time course of percent signal change in these regions for each condition beginning with the onset of the first stimulus of each pair, 1P. The blue bar represents the time of stimulus presentation, and the green bar represents the time of associative instruction presentation (plus sign). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

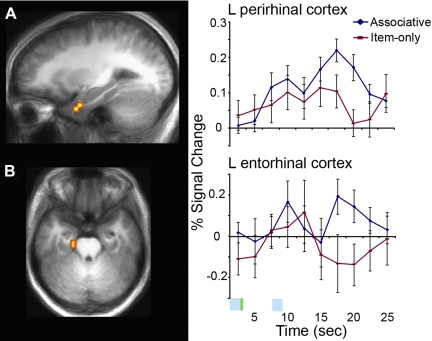

To examine the specific contribution of MTL regions to the successful binding of associative information, we isolated active voxels from the associative memory contrast (associative minus item-only trials, P < 0.05) that overlapped with the anatomically defined MTL substructures. These active voxel clusters were located in left PRC and left ERC (Fig. 3, A and B, and Table 2). Because of the size of the active voxel clusters in these small anatomical regions, these clusters did not survive cluster size-based correction for multiple comparisons and therefore were reported as uncorrected values. Similar to the activity reported in left frontal regions and lateral occipital/fusiform, left PRC and ERC showed a greater response during the encoding of 2P stimuli only when associative binding was successful. There were no voxels in MTL regions during the delay period showing greater activity for associative trials relative to item-only trials.

Fig. 3.

Activity in left perirhinal and entorhinal cortex predicts the successful associative binding of items. Statistical activation maps for regions showing increased activity during binding (P < 0.05, uncorrected) for associative trials compared with item-only trials are overlaid on sagittal and axial slices of mean anatomical scan images across all 15 subjects. Graphs depict the time course of percent signal change in left perirhinal (A) and entorhinal (B) cortices for each condition beginning with the onset of the first stimulus of each pair, 1P. These clusters were isolated from voxels functionally defined in the contrast of associative memory trials relative to item-only memory trials (P < 0.05) that were located in anatomically defined MTL regions, left perirhinal and entorhinal cortices. The blue bar represents the time of stimulus presentation, and the green bar represents the time of associative instruction presentation (plus sign). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

General item subsequent memory effects have been extensively explored in prior studies (beginning with Brewer et al. 1998 and Wagner et al. 1998), and such analyses were not the focus of the current study. Nevertheless, noted is the single activation predictive of high-confidence subsequent item (only) memory (P < 0.01) in right lateral occipital/fusiform cortex. These findings of both item and associative memory effects in lateral occipital/fusiform cortex complement results from a previous study (Hales and Brewer 2010) that found this area to be the only region of overlap between subsequent associative and item memory contrasts.

DISCUSSION

The current study identified subsequent memory effects in the MTL, PFC, and lateral occipital/fusiform cortex during associative encoding of temporally discontiguous images. Left frontal and lateral occipital cortices, like left PRC and ERC, showed increased activity during successful associative binding. Activity in these regions during the interitem delay, however, did not predict subsequent associative memory.

PRC/ERC involvement in associative memory formation.

When item memory strength was controlled for, subsequent associative memory effects for image pairs were found in left PRC and ERC in the present study. These results complement multiple studies that have reported the involvement of PRC, ERC, and other anterior regions of the MTL in successful associative encoding (Aminoff et al. 2007; Chua et al. 2007; Haskins et al. 2008; Jackson and Schacter 2004; Mayes et al. 2007; Peters et al. 2007; Pihlajamaki et al. 2003; Rauchs et al. 2008; Sperling et al. 2003; Staresina and Davachi 2009, 2010; Taylor et al. 2006). A recent study examining MTL activity for a visual associative memory task in which subjects saw objects presented against one of two backgrounds (providing source information) found increased right PRC activity for correct source encoding (Peters et al. 2007). The present finding of increased PRC activity during associative encoding has been supported in other studies examining memory for source information (Tendolkar et al. 2007), picture pairs (Pihlajamaki et al. 2003), word pairs (Jackson and Schacter 2004), and visual landmarks and their specific contexts (Rauchs et al. 2008), and the current study extends the involvement of the PRC to include the formation of associative memory for temporally discontiguous items.

Some studies, however, have reported PRC involvement only in item, and not associative, memory and instead highlight a separable role of the hippocampus in associative memory formation. A study examining the encoding of face-name pairs reported increased activity in anterior hippocampal formation for associative memory, whereas PRC activity was only increased for successful memory for the face items (Chua et al. 2007). Staresina and Davachi (2008) examined the function of PRC and the hippocampus during the encoding of item/color associations with or without additional associated context information. Both PRC and the hippocampus showed increased activity for subsequently remembered item/color associations, whereas the hippocampus showed an additional increase in activity when the context was also remembered in the association. The authors concluded that PRC may contribute to item-level associative encoding, whereas the hippocampus may be responsible for domain-general, including contextual, associative encoding (Staresina and Davachi 2008). Nevertheless, the interpretation of PRC involvement in item-level encoding is complicated, since this activity may also represent increased response to associative encoding within a domain; such findings are consistent with the results of the current study, which reports greater activity in PRC and ERC during associative encoding of two visual objects, which are of the same domain.

A recent study, in which subjects were shown two words and instructed either to encode the two words as a single novel compound word or to encode the two words in a sentence, has provided a possible explanation for the seemingly different roles attributed to PRC (Haskins et al. 2008). Increased activity was seen in left PRC during the encoding of the words as a single unit compared with encoding the words as two separate words in a sentence. The results of Haskins et al. (2008) suggest that PRC is involved in the associative encoding of items that can be represented as a single unit. This concept of PRC involvement when associated items are unitized has also been discussed in a recent review (Diana et al. 2007). To further examine the process of unitization in associative memory encoding, another recent study used fragmented objects that needed to be unitized when forming memory for the object and for the association between the object and its color (Staresina and Davachi 2010). PRC showed increased activity when the object was remembered relative to forgotten and even greater activity when the object-color association was subsequently remembered. A recent study described a possible model for how temporally discontiguous items could be associated, where neocortical working memory regions maintain the percept for an item across a delay period, allowing for concurrence between that active representation and a later one for associative binding (Hales and Brewer 2010). This model provides a possible mechanism for how a unitized association could be formed for temporally discontiguous items based on concurrent percepts of the two items at the time of binding. Nevertheless, the present study only suggests left PRC and ERC involvement in successful associative encoding; future investigation is needed to examine whether this involvement specifically predicts memory for a unitized percept that includes both objects or for a more flexible association of two separate items. In addition, these findings do not exclude the involvement of PRC in successful item encoding, but rather provide further evidence for PRC and ERC activity predicting successful associative encoding.

In addition to human imaging studies, the importance of PRC and ERC in associative encoding has been explored and supported by electrophysiological and lesion studies in nonhuman primates (Buckley and Gaffan 1998; Buckmaster et al. 2004; Fujimichi et al. 2010; Higuchi and Miyashita 1996; Miyashita and Chang 1988; Miyashita et al. 1998; Murray et al. 1993; Murray and Richmond 2001; Sakai and Miyashita 1991; Yanike et al. 2009; Yoshida et al. 2003). Sakai and Miyashita (1991) examined neuronal activity in anterior inferotemporal (IT) cortex in macaque monkeys while they performed a paired-associates task. After memorizing pairs of Fourier descriptors, monkeys were shown one image of a pair (cue) and were then shown two simultaneous patterns, one of which was the cue's pair. During this memory task, the authors conducted extracellular recordings of single neurons in anterior IT cortex and discovered the presence of associative memory-coding neurons (Sakai and Miyashita 1991). A follow-up study examined the importance of intact connections between PRC/ERC and IT cortex for the formation of the associative memory representation in IT (Higuchi and Miyashita 1996). Monkeys received anterior commissural transection and were then trained on the previously described visual paired-associates task. After the PRC and ERC were unilaterally lesioned, there was no longer evidence of associative memory coding in anterior IT cortex. The authors concluded that the integrity of PRC and ERC is necessary for the formation of associative memory representations for picture pairs in IT cortex (Higuchi and Miyashita 1996).

The presence of increased activity in PRC and ERC in humans during the encoding of visual paired-associates reported in the present study is in line with such electrophysiological and lesion data from nonhuman primates; however, despite all of the support from primate research for the function of PRC in associative encoding, determining the timing of PRC involvement in associative encoding events would be difficult, because monkeys require multiple presentations of the event to learn the task and association. Yanike et al. (2009) recorded from PRC in monkeys learning new associations of a scene and an eye-movement location, and particular location-scene associations were selected in which a significant difference in cell firing rate was measured between the first 5–10 trials and the last 5–10 trials. The authors found PRC cells involved in learning this association that changed their firing rate during the scene, the delay period, or both; however, regardless of the time period of firing rate change, the monkey had already learned the association. In the present study, since all stimuli are presented only once, the only time period at which the association can be known is after the second stimulus is presented and the associated items can be bound. Therefore, the current study allows examination of the temporal component of PRC involvement in associative encoding that cannot be addressed in primate studies that involve repeated presentation of events during learning.

Recent studies have reported prestimulus MTL activity that is predictive of subsequent recollection of incidentally or intentionally encoded words (Gruber and Otten 2010; Guderian et al. 2009; Park and Rugg 2010). Although the current study did not find delay period MTL activity differences between the conditions of interest (associative and item-only trials), these prior studies would suggest the presence of increased MTL activity just before the onset of subsequently remembered 2P items. It should be noted that since the 2P item was subsequently remembered in both conditions, this activity might be expected to be similar in these trial conditions of interest.

Subsequent associative memory effects in left PRC and ERC were only seen in the current study at the time that the 2P stimulus was presented and the association could be formed; there was not a subsequent associative memory effect during the delay period between the 1P and 2P stimuli. Whether the MTL is involved in the maintenance of stimuli over a short delay is an active area of research without consensus. Human lesion and imaging studies looking at working memory report mixed results of MTL involvement in delay period maintenance; however, there is a common distinction across most of these studies. MTL involvement in delay period maintenance is often reported in studies that used nonverbal stimuli, such as faces or abstract pictures (Axmacher et al. 2007; Ezzyat and Olson 2008; Grady et al. 1998; Hannula et al. 2006; Hartley et al. 2007; Monk et al. 2002; Nichols et al. 2006; Olson et al. 2006a; Picchioni et al. 2007; Piekema et al. 2006; Ranganath et al. 2004; Ranganath and D'Esposito 2001; Shrager et al. 2008; Stern et al. 2001), whereas MTL involvement in delay period maintenance is not often reported in studies that used verbal stimuli, such as words or nameable objects (Cave and Squire 1992; Habeck et al. 2005; Hales et al. 2009; Kessler and Kiefer 2005; Petit et al. 1998; Shrager et al. 2008; Talmi et al. 2005), although exceptions to this dissociation exist (Cabeza et al. 2002; Campo et al. 2005; Mencl et al. 2000; Olson et al. 2006b; Oztekin et al. 2009; Tesche and Karhu 2000). Although some researchers argue that the presence of MTL activity during delay period maintenance suggests MTL involvement in working memory, it is also possible that there is a categorical difference between maintaining verbalizable and nonverbalizable stimuli over a short delay and that working memory load capacity for these two types of stimuli is different. Therefore, maintenance of nonverbalizable stimuli may engage brain regions involved in long-term memory encoding, such as MTL regions, even for short delays.

This reasoning has been supported in studies examining working memory processing during a delayed match-to-sample task and subsequent long-term recognition memory (see Hasselmo and Stern 2006 for review; Schon et al. 2004, 2005). These studies have shown that the involvement of MTL structures in active maintenance is correlated with subsequent long-term memory recognition. A recent study has additionally probed this effect by showing that MTL activity is further modulated by working memory load in a task involving the maintenance of two or four unfamiliar, trial-unique complex visual outdoor scenes (Schon et al. 2009). Stern and colleagues (2001) also provide an alternative explanation for the presence of MTL activity during short delays in some studies, but not in others, as a distinction between the maintenance of familiar information versus novel information. Although PFC and parietal regions are commonly isolated for maintaining familiar representations during working memory delays, additional structures, including PRC/ERC, are recruited for creating a novel representation for maintenance (Hasselmo and Stern 2006). The current results, using verbalizable stimuli depicting simple common objects and showing no maintenance activity in the MTL, are in line with studies that have provided distinctions regarding MTL activity during short-delay maintenance of verbalizable (or possibly familiar) and nonverbalizable (or possibly novel) stimuli.

Frontal involvement and functional dissociation in associative memory formation.

In the current study, left DLPFC, VLPFC, and medial/middle frontal cortex all showed increased activity during the encoding of 2P stimuli that were subsequently recognized along with their corresponding associative pair (associative trials) compared with subsequently recognized 2P stimuli with forgotten associative information (item-only trials; Fig. 2, A–C). This finding of increased frontal activity for successful associative encoding is consistent with previous imaging, electrophysiology, and patient studies (Achim and Lepage 2005; Davachi and Wagner 2002; Dolan and Fletcher 1997; Geuze et al. 2008; Jackson and Schacter 2004; Kapur et al. 1996; Montaldi et al. 1998; Murray and Ranganath 2007; Pihlajamaki et al. 2003; Qin et al. 2007; Sperling et al. 2003; Staresina and Davachi 2006, 2010; Weyerts et al. 1997). Although these separate regions of the left frontal lobe all showed a subsequent associative memory effect, the response time course across the entire encoding event was categorically different in left VLPFC relative to left DLPFC and left medial/middle frontal cortex. Left DLPFC and medial/middle frontal cortex responded to both the 1P and 2P stimuli during associative and item-only trials, although the response to the 2P stimulus was larger for associative trials relative to item-only trials. Left VLPFC, however, only showed a response to the 2P stimulus for associative trials, with no response to the 1P stimulus or to either stimulus for item-only trials. Even though all three frontal regions predicted successful associative encoding, left VLPFC showed an increase in activity only during associative encoding, which is consistent with prior findings of selective VLPFC participation in associative memory formation (Blumenfeld et al. 2010; Blumenfeld and Ranganath 2006, 2007; Murray and Ranganath 2007; Tanabe and Sadato 2009; Wager and Smith 2003).

Involvement of lateral occipital cortex in associative encoding.

Increased left lateral occipital/fusiform activity was seen selectively for successful associative encoding in the present study. Lateral occipital cortex is commonly cited for its involvement in object recognition (Doehrmann et al. 2010; Grill-Spector et al. 2001; Malach et al. 1995; Murray et al. 2004), and some recent studies have described its specific role in visual imagery (Deshpande et al. 2010; Kaas et al. 2010; Lacey et al. 2010; Schendan and Stern 2008) and in object maintenance (Ferber et al. 2005; Harrison and Tong 2009). Lateral occipital cortex has also been found to play a role in the encoding of object-location source information (Cansino et al. 2002). In addition, a study examining lateral occipital-hippocampal correlations found increased functional correlations during rest following an associative encoding task with high subsequent memory performance (Tambini et al. 2010). As an extension of these findings of lateral occipital involvement in associative memory, the current study showed that increased lateral occipital activity during encoding selectively predicted subsequent associative memory for object pairs, even when controlling for the memory strength of the item being encoded. Increased lateral occipital activity at the time of associative binding might reflect the creation of a newly unitized percept that, when accessed at retrieval, supports associative memory performance; however, further investigation is needed to test such a putative underlying mechanism.

The current study confronts missing information regarding the time course of regional involvement in the associative encoding of temporally discontiguous visual objects pairs. Although the importance of PRC and ERC in associative memory formation has been well established in primate lesion and electrophysiology studies, such studies could not have answered questions about when these regions are involved in the successful encoding event. By temporally separating the subjects' exposure to each item of a pair and by showing subjects each pair only once, the current study extends prior studies, demonstrating that increased activity in left PFC, lateral occipital cortex, and anterior MTL happens once the pair is completed and predicts successful associative encoding of temporally discontiguous visual object pairs when item memory strength is controlled. Although some of these regions showed delay activity suggestive of object maintenance, this activity is simply part of attempting to encode the association and is not sufficient to show subsequent associative memory effects. The increase of activity in these frontal, lateral occipital, and MTL regions might represent binding and mnemonic storage of the new percept that incorporates the pair of stimuli or a conceptual or verbal association that links the objects.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant K23 NS050305 and the Departments of Neurosciences and Radiology at University of California, San Diego. J. B. Hales is supported by the National Science Foundation through the Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Achim AM, Lepage M. Neural correlates of memory for items and for associations: an event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Cogn Neurosci 17: 652–667, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminoff E, Gronau N, Bar M. The parahippocampal cortex mediates spatial and nonspatial associations. Cereb Cortex 17: 1493–1503, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axmacher N, Mormann F, Fernandez G, Cohen MX, Elger CE, Fell J. Sustained neural activity patterns during working memory in the human medial temporal lobe. J Neurosci 27: 7807–7816, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld RS, Parks CM, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Putting the pieces together: the role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in relational memory encoding. J Cogn Neurosci 23: 257–265, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld RS, Ranganath C. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex promotes long-term memory formation through its role in working memory organization. J Neurosci 26: 916–925, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld RS, Ranganath C. Prefrontal cortex and long-term memory encoding: an integrative review of findings from neuropsychology and neuroimaging. Neuroscientist 13: 280–291, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JB, Zhao Z, Desmond JE, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD. Making memories: brain activity that predicts how well visual experience will be remembered. Science 281: 1185–1187, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MJ, Gaffan D. Perirhinal cortex ablation impairs configural learning and paired-associate learning equally. Neuropsychologia 36: 535–546, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster CA, Eichenbaum H, Amaral DG, Suzuki WA, Rapp PR. Entorhinal cortex lesions disrupt the relational organization of memory in monkeys. J Neurosci 24: 9811–9825, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Dolcos F, Graham R, Nyberg L. Similarities and differences in the neural correlates of episodic memory retrieval and working memory. Neuroimage 16: 317–330, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahusac PM, Miyashita Y, Rolls ET. Responses of hippocampal formation neurons in the monkey related to delayed spatial response and object-place memory tasks. Behav Brain Res 33: 229–240, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo P, Maestu F, Ortiz T, Capilla A, Fernandez S, Fernandez A. Is medial temporal lobe activation specific for encoding long-term memories? Neuroimage 25: 34–42, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansino S, Maquet P, Dolan RJ, Rugg MD. Brain activity underlying encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cereb Cortex 12: 1048–1056, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave CB, Squire LR. Intact verbal and nonverbal short-term memory following damage to the human hippocampus. Hippocampus 2: 151–163, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua EF, Schacter DL, Rand-Giovannetti E, Sperling RA. Evidence for a specific role of the anterior hippocampal region in successful associative encoding. Hippocampus 17: 1071–1080, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 29: 162–173, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 8: 109–114, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Buckner RL. Selective averaging of rapidly presented individual trials using fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 5: 329–340, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daselaar SM, Fleck MS, Cabeza R. Triple dissociation in the medial temporal lobes: recollection, familiarity, and novelty. J Neurophysiol 96: 1902–1911, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr Opin Neurobiol 16: 693–700, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L, Mitchell JP, Wagner AD. Multiple routes to memory: distinct medial temporal lobe processes build item and source memories. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 2157–2162, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L, Wagner AD. Hippocampal contributions to episodic encoding: insights from relational and item-based learning. J Neurophysiol 88: 982–990, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deco G, Ledberg A, Almeida R, Fuster J. Neural dynamics of cross-modal and cross-temporal associations. Exp Brain Res 166: 325–336, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande G, Hu X, Lacey S, Stilla R, Sathian K. Object familiarity modulates effective connectivity during haptic shape perception. Neuroimage 49: 1991–2000, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: a three-component model. Trends Cogn Sci 11: 379–386, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehrmann O, Weigelt S, Altmann CF, Kaiser J, Naumer MJ. Audiovisual functional magnetic resonance imaging adaptation reveals multisensory integration effects in object-related sensory cortices. J Neurosci 30: 3370–3379, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan RJ, Fletcher PC. Dissociating prefrontal and hippocampal function in episodic memory encoding. Nature 388: 582–585, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 30: 123–152, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzyat Y, Olson IR. The medial temporal lobe and visual working memory: comparisons across tasks, delays, and visual similarity. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 8: 32–40, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber S, Humphrey GK, Vilis T. Segregation and persistence of form in the lateral occipital complex. Neuropsychologia 43: 41–51, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimichi R, Naya Y, Koyano KW, Takeda M, Takeuchi D, Miyashita Y. Unitized representation of paired objects in area 35 of the macaque perirhinal cortex. Eur J Neurosci 32: 659–667, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furtak SC, Wei SM, Agster KL, Burwell RD. Functional neuroanatomy of the parahippocampal region in the rat: the perirhinal and postrhinal cortices. Hippocampus 17: 709–722, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM, Bodner M, Kroger JK. Cross-modal and cross-temporal association in neurons of frontal cortex. Nature 405: 347–351, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuze E, Vermetten E, Ruf M, de Kloet CS, Westenberg HG. Neural correlates of associative learning and memory in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res 42: 659–669, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JJ, Smith CN, Bayley PJ, Shrager Y, Brewer JB, Stark CE, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Item memory, source memory, and the medial temporal lobe: concordant findings from fMRI and memory-impaired patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9351–9356, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Bookstein F, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI, Haxby JV. Age-related changes in regional cerebral blood flow during working memory for faces. Neuroimage 8: 409–425, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill-Spector K, Kourtzi Z, Kanwisher N. The lateral occipital complex and its role in object recognition. Vision Res 41: 1409–1422, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber MJ, Otten LJ. Voluntary control over prestimulus activity related to encoding. J Neurosci 30: 9793–9800, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guderian S, Schott BH, Richardson-Klavehn A, Duzel E. Medial temporal theta state before an event predicts episodic encoding success in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5365–5370, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habeck C, Rakitin BC, Moeller J, Scarmeas N, Zarahn E, Brown T, Stern Y. An event-related fMRI study of the neural networks underlying the encoding, maintenance, and retrieval phase in a delayed-match-to-sample task. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 23: 207–220, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales JB, Brewer JB. Activity in the hippocampus and neocortical working memory regions predicts successful associative memory for temporally discontiguous events. Neuropsychologia 48: 3351–3359, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales JB, Israel SL, Swann NC, Brewer JB. Dissociation of frontal and medial temporal lobe activity in maintenance and binding of sequentially presented paired associates. J Cogn Neurosci 21: 1244–1254, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Temporal firing characteristics and the strategic role of subicular neurons in short-term memory. Hippocampus 13: 529–541, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula DE, Tranel D, Cohen NJ. The long and the short of it: relational memory impairments in amnesia, even at short lags. J Neurosci 26: 8352–8359, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SA, Tong F. Decoding reveals the contents of visual working memory in early visual areas. Nature 458: 632–635, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley T, Bird CM, Chan D, Cipolotti L, Husain M, Vargha-Khadem F, Burgess N. The hippocampus is required for short-term topographical memory in humans. Hippocampus 17: 34–48, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins AL, Yonelinas AP, Quamme JR, Ranganath C. Perirhinal cortex supports encoding and familiarity-based recognition of novel associations. Neuron 59: 554–560, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Mechanisms underlying working memory for novel information. Trends Cogn Sci 10: 487–493, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Miyashita Y. Formation of mnemonic neuronal responses to visual paired associates in inferotemporal cortex is impaired by perirhinal and entorhinal lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 739–743, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Juottonen K, Soininen H, Insausti AM, Partanen K, Vainio P, Laakso MP, Pitkanen A. MR volumetric analysis of the human entorhinal, perirhinal, and temporopolar cortices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 19: 659–671, 1998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson O, 3rd, Schacter DL. Encoding activity in anterior medial temporal lobe supports subsequent associative recognition. Neuroimage 21: 456–462, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas A, Weigelt S, Roebroeck A, Kohler A, Muckli L. Imagery of a moving object: the role of occipital cortex and human MT/V5+. Neuroimage 49: 794–804, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Tulving E, Cabeza R, McIntosh AR, Houle S, Craik FI. The neural correlates of intentional learning of verbal materials: a PET study in humans. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 4: 243–249, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler K, Kiefer M. Disturbing visual working memory: electrophysiological evidence for a role of the prefrontal cortex in recovery from interference. Cereb Cortex 15: 1075–1087, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff BA, Wagner AD, Maril A, Stern CE. Prefrontal-temporal circuitry for episodic encoding and subsequent memory. J Neurosci 20: 6173–6180, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, Jones CK, Miller MI, Stark CE. High-resolution fMRI investigation of the medial temporal lobe. Hum Brain Mapp 28: 959–966, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan CB, Stark CE. Medial temporal lobe activation during encoding and retrieval of novel face-name pairs. Hippocampus 14: 919–930, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkel A, Warren DE, Duff MC, Tranel DN, Cohen NJ. Hippocampal amnesia impairs all manner of relational memory. Front Hum Neurosci 2: 15, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey S, Flueckiger P, Stilla R, Lava M, Sathian K. Object familiarity modulates the relationship between visual object imagery and haptic shape perception. Neuroimage 49: 1977–1990, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malach R, Reppas JB, Benson RR, Kwong KK, Jiang H, Kennedy WA, Ledden PJ, Brady TJ, Rosen BR, Tootell RB. Object-related activity revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging in human occipital cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 8135–8139, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes A, Montaldi D, Migo E. Associative memory and the medial temporal lobes. Trends Cogn Sci 11: 126–135, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mencl WE, Pugh KR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Fulbright RK, Constable RT, Skudlarski P, Katz L, Marchione KE, Lacadie C, Gore JC. Network analysis of brain activations in working memory: behavior and age relationships. Microsc Res Tech 51: 64–74, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MI, Beg MF, Ceritoglu C, Stark C. Increasing the power of functional maps of the medial temporal lobe by using large deformation diffeomorphic metric mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9685–9690, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y, Chang HS. Neuronal correlate of pictorial short-term memory in the primate temporal cortex. Nature 331: 68–70, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita Y, Kameyama M, Hasegawa I, Fukushima T. Consolidation of visual associative long-term memory in the temporal cortex of primates. Neurobiol Learn Mem 70: 197–211, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Zhuang J, Curtis WJ, Ofenloch IT, Tottenham N, Nelson CA, Hu X. Human hippocampal activation in the delayed matching- and nonmatching-to-sample memory tasks: an event-related functional MRI approach. Behav Neurosci 116: 716–721, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaldi D, Mayes AR, Barnes A, Pirie H, Hadley DM, Patterson J, Wyper DJ. Associative encoding of pictures activates the medial temporal lobes. Hum Brain Mapp 6: 85–104, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Gaffan D, Mishkin M. Neural substrates of visual stimulus-stimulus association in rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci 13: 4549–4561, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Richmond BJ. Role of perirhinal cortex in object perception, memory, and associations. Curr Opin Neurobiol 11: 188–193, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LJ, Ranganath C. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex contributes to successful relational memory encoding. J Neurosci 27: 5515–5522, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MM, Michel CM, Grave de Peralta R, Ortigue S, Brunet D, Gonzalez Andino S, Schnider A. Rapid discrimination of visual and multisensory memories revealed by electrical neuroimaging. Neuroimage 21: 125–135, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols EA, Kao YC, Verfaellie M, Gabrieli JD. Working memory and long-term memory for faces: Evidence from fMRI and global amnesia for involvement of the medial temporal lobes. Hippocampus 16: 604–616, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Moore KS, Stark M, Chatterjee A. Visual working memory is impaired when the medial temporal lobe is damaged. J Cogn Neurosci 18: 1087–1097, 2006a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Page K, Moore KS, Chatterjee A, Verfaellie M. Working memory for conjunctions relies on the medial temporal lobe. J Neurosci 26: 4596–4601, 2006b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oztekin I, McElree B, Staresina BP, Davachi L. Working memory retrieval: contributions of the left prefrontal cortex, the left posterior parietal cortex, and the hippocampus. J Cogn Neurosci 21: 581–593, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Rugg MD. Prestimulus hippocampal activity predicts later recollection. Hippocampus 20: 24–28, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Suchan B, Koster O, Daum I. Domain-specific retrieval of source information in the medial temporal lobe. Eur J Neurosci 26: 1333–1343, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit L, Courtney SM, Ungerleider LG, Haxby JV. Sustained activity in the medial wall during working memory delays. J Neurosci 18: 9429–9437, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picchioni M, Matthiasson P, Broome M, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Mathes B, Fletcher P, Williams S, McGuire P. Medial temporal lobe activity at recognition increases with the duration of mnemonic delay during an object working memory task. Hum Brain Mapp 28: 1235–1250, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekema C, Kessels RP, Mars RB, Petersson KM, Fernandez G. The right hippocampus participates in short-term memory maintenance of object-location associations. Neuroimage 33: 374–382, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamaki M, Tanila H, Hanninen T, Kononen M, Mikkonen M, Jalkanen V, Partanen K, Aronen HJ, Soininen H. Encoding of novel picture pairs activates the perirhinal cortex: an fMRI study. Hippocampus 13: 67–80, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston AR, Gabrieli JD. Dissociation between explicit memory and configural memory in the human medial temporal lobe. Cereb Cortex 18: 2192–2207, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Piekema C, Petersson KM, Han B, Luo J, Fernandez G. Probing the transformation of discontinuous associations into episodic memory: an event-related fMRI study. Neuroimage 38: 212–222, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Rijpkema M, Tendolkar I, Piekema C, Hermans EJ, Binder M, Petersson KM, Luo J, Fernandez G. Dissecting medial temporal lobe contributions to item and associative memory formation. Neuroimage 46: 874–881, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Cohen MX, Dam C, D'Esposito M. Inferior temporal, prefrontal, and hippocampal contributions to visual working memory maintenance and associative memory retrieval. J Neurosci 24: 3917–3925, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, D'Esposito M. Medial temporal lobe activity associated with active maintenance of novel information. Neuron 31: 865–873, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauchs G, Orban P, Balteau E, Schmidt C, Degueldre C, Luxen A, Maquet P, Peigneux P. Partially segregated neural networks for spatial and contextual memory in virtual navigation. Hippocampus 18: 503–518, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Pourtois G. Revisiting Snodgrass and Vanderwart's object pictorial set: the role of surface detail in basic-level object recognition. Perception 33: 217–236, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Miyashita Y. Neural organization for the long-term memory of paired associates. Nature 354: 152–155, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schendan HE, Stern CE. Where vision meets memory: prefrontal-posterior networks for visual object constancy during categorization and recognition. Cereb Cortex 18: 1695–1711, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Atri A, Hasselmo ME, Tricarico MD, LoPresti ML, Stern CE. Scopolamine reduces persistent activity related to long-term encoding in the parahippocampal gyrus during delayed matching in humans. J Neurosci 25: 9112–9123, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Hasselmo ME, Lopresti ML, Tricarico MD, Stern CE. Persistence of parahippocampal representation in the absence of stimulus input enhances long-term encoding: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study of subsequent memory after a delayed match-to-sample task. J Neurosci 24: 11088–11097, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon K, Quiroz YT, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE. Greater working memory load results in greater medial temporal activity at retrieval. Cereb Cortex 19: 2561–2571, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrager Y, Levy DA, Hopkins RO, Squire LR. Working memory and the organization of brain systems. J Neurosci 28: 4818–4822, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, Suppl 1: S208–S219, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer T, Rose M, Glascher J, Wolbers T, Buchel C. Dissociable contributions within the medial temporal lobe to encoding of object-location associations. Learn Mem 12: 343–351, 2005a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer T, Rose M, Weiller C, Buchel C. Contributions of occipital, parietal and parahippocampal cortex to encoding of object-location associations. Neuropsychologia 43: 732–743, 2005b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R, Chua E, Cocchiarella A, Rand-Giovannetti E, Poldrack R, Schacter DL, Albert M. Putting names to faces: successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. Neuroimage 20: 1400–1410, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Davachi L. Differential encoding mechanisms for subsequent associative recognition and free recall. J Neurosci 26: 9162–9172, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Davachi L. Mind the gap: binding experiences across space and time in the human hippocampus. Neuron 63: 267–276, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Davachi L. Object unitization and associative memory formation are supported by distinct brain regions. J Neurosci 30: 9890–9897, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Davachi L. Selective and shared contributions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex to episodic item and associative encoding. J Cogn Neurosci 20: 1478–1489, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark CE, Okado Y. Making memories without trying: medial temporal lobe activity associated with incidental memory formation during recognition. J Neurosci 23: 6748–6753, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern CE, Sherman SJ, Kirchhoff BA, Hasselmo ME. Medial temporal and prefrontal contributions to working memory tasks with novel and familiar stimuli. Hippocampus 11: 337–346, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki WA, Amaral DG. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices of the macaque monkey: cortical afferents. J Comp Neurol 350: 497–533, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Naya Y, Fujimichi R, Takeuchi D, Miyashita Y. Active maintenance of associative mnemonic signal in monkey inferior temporal cortex. Neuron 48: 839–848, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. A Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Talmi D, Grady CL, Goshen-Gottstein Y, Moscovitch M. Neuroimaging the serial position curve. A test of single-store versus dual-store models. Psychol Sci 16: 716–723, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambini A, Ketz N, Davachi L. Enhanced brain correlations during rest are related to memory for recent experiences. Neuron 65: 280–290, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe HC, Sadato N. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activity associated with individual differences in arbitrary delayed paired-association learning performance: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience 160: 688–697, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KI, Moss HE, Stamatakis EA, Tyler LK. Binding crossmodal object features in perirhinal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8239–8244, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tendolkar I, Arnold J, Petersson KM, Weis S, Anke BD, van Eijndhoven P, Buitelaar J, Fernandez G. Probing the neural correlates of associative memory formation: a parametrically analyzed event-related functional MRI study. Brain Res 1142: 159–168, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesche CD, Karhu J. Theta oscillations index human hippocampal activation during a working memory task. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 919–924, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar TR, Salzmann E, Creutzfeldt OD. Unit activity in the hippocampus and the parahippocampal temporobasal association cortex related to memory and complex behaviour in the awake monkey. Brain Res 544: 269–278, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging studies of working memory: a meta-analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 3: 255–274, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AD, Schacter DL, Rotte M, Koutstaal W, Maril A, Dale AM, Rosen BR, Buckner RL. Building memories: remembering and forgetting of verbal experiences as predicted by brain activity. Science 281: 1188–1191, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Niki H. Hippocampal unit activity and delayed response in the monkey. Brain Res 325: 241–254, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyerts H, Tendolkar I, Smid HG, Heinze HJ. ERPs to encoding and recognition in two different inter-item association tasks. Neuroreport 8: 1583–1588, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanike M, Wirth S, Smith AC, Brown EN, Suzuki WA. Comparison of associative learning-related signals in the macaque perirhinal cortex and hippocampus. Cereb Cortex 19: 1064–1078, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Naya Y, Miyashita Y. Anatomical organization of forward fiber projections from area TE to perirhinal neurons representing visual long-term memory in monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4257–4262, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young BJ, Otto T, Fox GD, Eichenbaum H. Memory representation within the parahippocampal region. J Neurosci 17: 5183–5195, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]