Abstract

Norepinephrine (NE) is a strong modulator and/or activator of spinal locomotor networks. Thus noradrenergic fibers likely contact neurons involved in generating locomotion. The aim of the present study was to investigate the noradrenergic innervation of functionally related, locomotor-activated neurons within the thoraco-lumbar spinal cord. This was accomplished by immunohistochemical colocalization of noradrenergic fibers using dopamine-β-hydroxylase or NEα1A and NEα2B receptors with cells expressing the c-fos gene activity-dependent marker Fos. Experiments were performed on paralyzed, precollicular-postmamillary decerebrate cats, in which locomotion was induced by electrical stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region. The majority of Fos labeled neurons, especially abundant in laminae VII and VIII throughout the thoraco-lumbar (T13-L7) region of locomotor animals, showed close contacts with multiple noradrenergic boutons. A small percentage (10–40%) of Fos neurons in the T7-L7 segments showed colocalization with NEα1A receptors. In contrast, NEα2B receptor immunoreactivity was observed in 70–90% of Fos cells, with no obvious rostrocaudal gradient. In comparison with results obtained from our previous study on the same animals, a significantly smaller proportion of Fos labeled neurons were innervated by noradrenergic than serotonergic fibers, with significant differences observed for laminae VII and VIII in some segments. In lamina VII of the lumbar segments, the degree of monoaminergic receptor subtype/Fos colocalization examined statistically generally fell into the following order: NEα2B = 5-HT2A ≥ 5-HT7 = 5-HT1A > NEα1A. These results suggest that noradrenergic modulation of locomotion involves NEα1A/NEα2B receptors on noradrenergic-innervated locomotor-activated neurons within laminae VII and VIII of thoraco-lumbar segments. Further study of the functional role of these receptors in locomotion is warranted.

Keywords: immunocytochemistry, ceruleospinal, mesencephalic locomotor region, activity-dependent labeling

neurons within the spinal cord are densely innervated by noradrenergic fibers originating from the locus ceruleus, the more diffuse, adjacent subcerulear nucleus and the Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, which provide the primary sources of catecholamine innervation of the lumbar spinal cord in the cat (Jones and Friedman 1983; Maeda et al. 1973; Stevens et al. 1982). A number of studies have examined the synaptic relation of noradrenergic fibers on various identified spinal neurons (e.g., Doyle and Maxwell 1993; Hammar and Maxwell 2002; Hammar et al. 2004; Maxwell et al. 2000) and the distribution of noradrenergic receptor subtypes within the spinal cord (Giroux et al. 1999; Roudet et al. 1993–1995; Stone et al. 1998; Uhlén et al. 1997; Wada et al. 1996). However, no studies have examined these relationships with respect to spinal locomotor neurons. Because norepinephrine (NE) or its precursor L-dihydroxy-phenylalanine (L-DOPA) may induce or modulate ongoing locomotor activity (Barbeau et al. 1987; Barbeau and Rossignol 1991; Chau et al. 1998; Grillner and Zangger 1979; Jankowska et al. 1967; Kiehn et al. 1992, 1999), it is likely that noradrenergic fibers innervate locomotor neurons and through the release of NE influence their activity. Although it can be expected that most noradrenergic innervation is synaptic in nature (Doyle and Maxwell 1991, 1993; Hagihira et al. 1990), some studies have documented significant nonsynaptic noradrenergic terminations in spinal tissue (Doyle and Maxwell 1993; Hammar and Maxwell 2002; Rajaofetra et al. 1992; Ridet et al. 1993) similar to that seen for serotonergic projections (e.g., Jankowska et al. 1997; Marlier et al. 1991; Ridet et al. 1993). Extrasynaptic overflow of norepinephrine within the spinal cord has also been observed following electrical stimulation of the locus ceruleus (Hentall et al. 2003) and the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR; Noga et al. 2006, 2007), providing additional evidence that descending noradrenergic pathways likely use volume transmission (Agnati et al. 1995) as a means to control spinal neurons. In the locus ceruleus, norepinephrine may diffuse up to 10 μm from the site of release before interacting with autoreceptors and transporters (Callado and Stamford 2000), indicating that the spatial requirements of nonsynaptic noradrenergic transmission are not as strict as those involved in synaptic transmission.

This study continues the examination of thoraco-lumbar neurons (Noga et al. 2009) centrally activated to produce locomotor activity in the absence of cyclical sensory feedback from moving limbs, i.e., during fictive locomotion (Noga et al. 1995, 2003). It documents the distribution of these locomotor-activated neurons with soma and proximal dendrites that are innervated by or in close proximity (apposed) to noradrenergic terminals and examines whether they possess postsynaptic adrenergic NEα1A and NEα2B receptors. Pharmacological studies indicate that both NEα1 and NEα2 receptors are involved in the initiation and/or modulation of hindlimb locomotor activity in the cat (Barbeau and Rossignol 1991; Brustein and Rossignol 1999; Chau et al. 1998; Delivet-Mongrain et al. 2008; Giroux et al. 2001; Marcoux and Rossignol 2000) and rodent (Gordon and Whelan 2006; Majczyński et al. 2006; Sqalli-Houssaini and Cazalets 2000; see also Kiehn et al. 1999). These receptor subtypes were chosen for a variety of reasons. NEα1A (Wada et al. 1996) and NEα2B postsynaptic receptors (Smith et al. 1995) predominate in the rat and human spinal cord, respectively, and are found in abundance in intermediate and ventral laminae in the lumbar region (Day et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1995) where locomotor activated neurons predominate (Dai et al. 2005). In contrast, a substantial proportion of NEα2A receptors may be expressed on primary afferent and other central terminals (Riedl et al. 2009; Stone et al. 1998) and may be involved in presynaptic regulation of NE release (Li et al. 2000; Umeda et al. 1997). The middle-lower lumbar segments were chosen for immunohistochemical processing since they contain neurons believed to be involved in the production of hindlimb locomotion (Dai et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2000; Noga et al. 1995). The lower thoracic/upper lumbar segments were also taken for comparison since this area is known to play a major role in generating locomotion in the rat (Bertrand and Cazalets 2002; Cazalets et al. 1995; Kjaerulff and Kiehn 1996). We used fluorescent c-fos gene expression (Fos immunohistochemistry: Herdeen and Leah 1998) as a marker of neuronal activity in large populations/chains of neurons following MLR induced fictive locomotion (Dai et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2000; Noga et al. 2009) and dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DβH)-immunoreactivity to label noradrenergic fibers (Doyle and Maxwell 1991, 1993; Hartman 1973).

The results demonstrate that substantial numbers of locomotor-activated spinal neurons in thoraco-lumbar segments are innervated by or are in close proximity to noradrenergic boutons and possess NEα2B receptors. A smaller percentage of locomotor-activated neurons colocalize with the NEα1A receptor. The data reveal an anatomical basis for noradrenergic modulation and activation of hindlimb locomotor activity and support the concept that MLR evoked locomotion is mediated by the parallel activation of descending reticulospinal (Noga et al. 2003) and monoaminergic (Noga et al. 2006, 2007, 2008) pathways. They also indicate that laminae VII and VIII are likely sites for noradrenergic influences (via NEα1A and NEα2B receptors) on the centrally activated locomotor network in the cat. Preliminary results were reported previously (Johnson et al. 2002).

METHODS

Animal Preparation/Stimulation and Data Collection

Experiments were carried out on adult cats (Felis silvestris catus) in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23; revised 1996) and following local approval by the University of Miami's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The number of animals used, and their pain and distress, was minimized. The experimental analysis was carried out tissue obtained from the same animals as in our previous publication (Noga et al. 2009), where the details of the experimental preparation, stimulation, and data collection are described. In all experiments reported here, there was a 10-h interval between decerebration and perfusion to minimize the Fos expression resulting from surgery.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen tissue sections of 30-μm thickness were sectioned coronally with a sliding microtome and collected in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Optimization of the immunohistochemical procedures was achieved using a small group of sections randomly collected from the rostral half of each lumbar segment or from cervical segments and by performing a primary antibody dilution series. In addition, for the preadsorption control, tissue sections were incubated only with preimmuno serum without the primary antibodies. Immunoreactivity was totally absent after omission of the primary antibodies. A group of equally spaced sections was processed with immunohistochemical procedures to label Fos and DβH fibers (18 sections each for a total of 540 μm). To visualize Fos, the sections were prewashed in 0.1 M PBS, rinsed in 0.3% H2O2 and PBS, and then blocked in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum (NGS) albumin (S-1000: Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at room temperature. They were then incubated for 48 h in rabbit polyclonal anti-Fos protein IgG (PC38–100U: Oncogene Research Products/Calbiochem, San Diego, CA: generated against synthetic peptide sequence corresponding to amino acids 4–17 of human c-fos and recognizing the ∼55 kDa c-fos and ∼62 kDa v-fos proteins), 1:2,500 in 0.2 M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% NGS albumin at 4°C. Sections were incubated overnight with mouse monoclonal anti-DβH IgG (MAB308: Chemicon International, Temecula, CA: generated against purified bovine DβH), 1:500 in 0.3% Triton X-100, and 5% NGS at 4°C. Each secondary antibody was conjugated to a different fluorophore (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA): Alexa 488 (green) for Fos (1:500; goat anti-rabbit, A-11008) and Alexa 594 (red) for DβH (1:500; goat anti-mouse, A-11005). Incubations were for 90 min in 0.1 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% NGS. Incubations with each secondary antibody were performed following each primary (Fos protocol first). A number of sections were also incubated for 15 min in NeuroTrace 640 Nissl (blue) in PBS (1:100) at room temperature. For NEα1A receptor immunocytochemistry, sections blocked in 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) albumin (S30: Chemicon International) were either reacted with rabbit polyclonal anti-Fos IgG (as above) or with mouse monoclonal anti-Fos IgG (sc-8047: Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA: raised against a recombinant protein corresponding to amino acids 210–335 mapping at the carboxy terminus of Fos p62 of human origin) 1:300 in 5% NDS. Following incubation with their secondary antibody (see below), they were subsequently incubated with affinity purified goat polyclonal anti-NEα1A receptor (sc-1477; Santa Cruz Biotechnology: generated against a peptide mapping at the C-terminus of the human α1A-adrenergic receptor; cloned α1c and redesignated α1a/c) 1:100 in 5% NDS (24–48 h at 4°C). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa 488 for Fos (1:500, donkey anti-rabbit, A-21206 or 1:200, donkey anti-mouse, A-21202; 3% NDS) and Alexa 594 (1:200; donkey anti-goat, A-11058; 3–5% NDS). Incubations were for 90–180 min in 0.1 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100. For NEα2B receptor immunocytochemistry, sections blocked in 10% NDS and reacted with the mouse monoclonal anti-Fos IgG (1:300 in 5% NDS) were incubated with affinity purified goat polyclonal anti-NEα2B receptor (sc-1479; Santa Cruz Biotechnology: generated against a peptide mapping at the C-terminus of the human α2B-adrenergic receptor) 1:100 in 5% NDS (24–48 h at 4°C). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa 488 for Fos (1:500; donkey anti-rabbit, A-21206; 3% NDS) and Alexa 594 (1:200; donkey anti-goat, A-11058; 3–5% NDS). Incubations were for 90 min in 0.1 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100. Sections were mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides, dried for 1 h at room temperature, and coated with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and then coverslipped and stored at 4°C.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Sections were examined primarily with Zeiss Axioline microscopes using fluorescence microscopy. Cells were mapped using Neurolucida software. Cell counts were done using stereologic cell counting methods (Stereo Investigator 5.0, Microbrightfield Bioscience, Williston, VT) giving estimates of cell number per segment in different laminae. Confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM510, with Ar multiline and HeN1 564) was used to examine the spatial orientation of the noradrenergic terminals apposing selected cells.

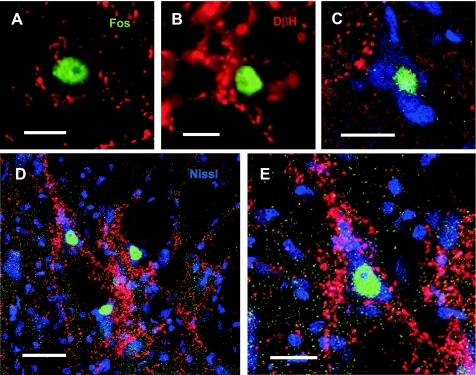

Fos-positive neurons needed to be intimately surrounded by noradrenergic terminals (juxtaposed or in close contact) to be considered as being innervated by noradrenergic fibers. Criteria used to define this relationship were: 1) the presynaptic element must be a swelling of the axon; 2) the postsynaptic element must contain a Fos positive nucleus; 3) the presynaptic and postsynaptic elements should be juxtaposed with little or no intervening space between them, i.e., the structures should be resolvable by minimal focusing adjustments (see also Alvarez et al. 1998; Jankowska et al. 1995; Pearson et al. 2000). In cases where Nissl-stained sections were analyzed, and their somas were clearly observed, the presence of close contacts was unequivocal (Fig. 1C). In sections without Nissl-staining, cells were scored as being in close contact when the orientation of DβH-immunoreactive fibers and terminals delineated a somal space surrounding the Fos positive nucleus (Fig. 1, A and B). The concurrence between the percentage of colocalized NEα2B receptor and DβH contacted Fos positive cells validates the reliability of this method (see results).

Fig. 1.

Representative immunocytochemical identification of locomotor-activated neurons by Fos nuclear labeling (green), juxtaposed to fibers and varicosities (red) stained positive for DβH. Cells in A and B are located in lamina VII of lumbar (L6) and thoracic (T13) segments, respectively. Cells in C–E have additionally Nissl-stained (blue) cytoplasm. Multiple contacts can be seen on the soma and proximal dendrites of cells in D (higher magnification in E), and approximate, but do not contact the soma of the cell in C. Cells are located in lamina VII of L2 (D and E) and L4 (C) segments. Confocal images are in A and C (optical slice) and D and E (projections); fluorescence microscope image is in B. Scale bars: 20 μm (A, C, and E), 10 μm (B), 40 μm (D).

Differences in the number of DβH innervated cells per section between control and locomotor cats 1 and 2 (LC1, LC2) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni corrected post hoc test. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance level of P ≤ 0.05. Paired-samples t-tests (with Bonferroni corrections to compensate for multiple comparisons) were made to compare means of two variables for a single group in comparisons between noradrenergic and serotonergic innervations and receptor colocalizations (see also Noga et al. 2009). Statistical tests were made using Systat statistical software, version 12.0 (Point Richmond, CA) or SPSS statistical software, version 18.0 (PASW Statistics 18, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Four-limbed locomotion was evoked by stimulation of the MLR in both experimental animals, for a total of ∼3.25–4.50 h over a period of ∼5 to 6.5 h as described previously (Noga et al. 2009). The brainstem and spinal cord viability was comparable in control and locomotor cats since the control animal was also capable of four-limbed locomotion, but was stimulated only briefly (∼1 min), 7 h before perfusion.

DβH/Fos Immunohistochemistry

Numerous spinal neurons identified by their Fos labeled nuclei were observed in the locomotor cats (Fig. 1). In the majority of cases, fibers and varicosities stained positive for DβH were juxtaposed to these neurons. The terminals of noradrenergic axons were often seen in clusters, coursing across the soma with multiple boutons/fiber in close proximity to the surface (Fig. 1, A, B, D, E). In other cases, noradrenergic terminals were not in observed in close apposition to Fos stained cells and were not scored as contacting these neurons (Fig. 1C). The relationship of DβH fibers and neurons staining positive for Fos was examined in multiple spinal sections, and maps of the noradrenergic innervation of these neurons for thoracolumbar segments T13-L7 were constructed for control and locomotor animals (Fig. 2).

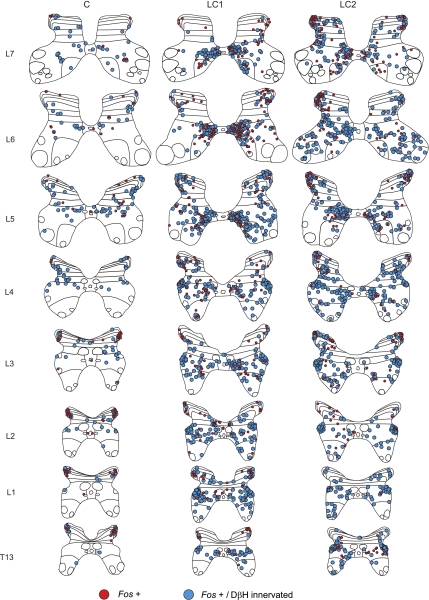

Fig. 2.

Maps showing the distribution of Fos immunoreactive neurons with or without noradrenergic contacts in the T13-L7 thoraco-lumbar spinal segments of control (C) and locomotor cats 1 (LC1) and 2 (LC2). Fos positive cells with noradrenergic contacts are indicated with blue circles. Those without are indicated with red circles. Each diagram includes all labeled cells from 18 sections of that segment. Each dot represents 1 labeled cell in this and other figures. In the control animal, labeled cells were lightly scattered in the dorsal horn and intermediate zone. Many of these neurons showed noradrenergic contacts. Substantially more cells were seen in animals undergoing fictive locomotion than in the control. Greatest numbers of contacted cells were observed in lamina VII, with a tendency for these cells to cluster in medial areas in lower lumbar segments. The spinal laminae illustrated for each segment in this and other figures are identified according to the classification of Rexed (1954).

Nonlocomotor control experiment.

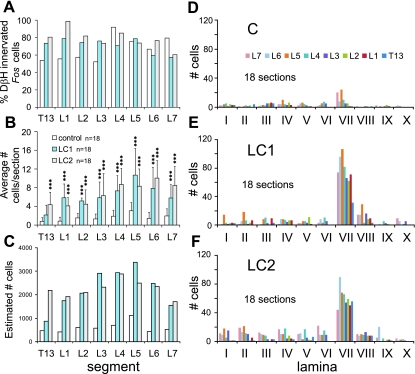

Spinal segments in the control animal showed small numbers of neurons containing Fos labeled nuclei (Fig. 2). The percentage of Fos positive cells innervated by noradrenergic fibers was between 50% and 90% (Fig. 3A) with upper segments (T13-L3) showing a slightly lower percentage overall. Most of these cells were found scattered in the dorsal horn with additional cells in intermediate zone areas and few within the ventral horn (Figs. 2 and 3D). The average number of innervated cells in each section was typically below three (Fig. 3B). Estimates of their total number in each segment (as determined from the number of cells found in each series of cut sections and projected over the entire length of the segment) were typically under 700, with an estimated peak of 1,000 for the L5 lumbar segment (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Percentage and distribution (segmental and laminar) of noradrenergic innervated Fos immunoreactive neurons observed within the T13-L7 thoraco-lumbar segments of control and locomotor animals. The percentage of noradrenergic innervated Fos labeled cells observed in each segment of LC1, LC2, and C cats is compared in A. Approximately 60–100% of the cells showed noradrenergic contacts. The total number of cells per section (mean ± SD) for each segment is illustrated in B. Middle and caudal lumbar segments showed the largest number of labeled cells per section (peaking in L5 and L6 lumbar segments for LC1 and LC2, respectively). The total number of innervated cells per section was significantly greater in cats undergoing locomotion (***P < 0.001) than in the control, with the exception of the T13 segment for LC1 (see results). The number of locomotor-activated neurons estimated for each segment (taking into account the length/volume of each segment) is plotted in C. According to this estimate, the number of noradrenergic-contacted neurons peaks in the L4 and L5 lumbar segments of locomotor animals. The laminar distributions of noradrenergic innervated neurons within the different segments from locomotor and control animals are shown in D–F. The number of noradrenergic innervated Fos immunoreactive neurons was dramatically and significantly increased in lamina VII of locomotor animals (all segments) compared with control values (with largest numbers found in L5/L6 lumbar segments). This increase was significantly greater in cats undergoing locomotion (***P < 0.001) than in the control.

Locomotion experiments.

The locomotor task produced a clear increase in Fos labeled cells in the intermediate zone and ventral horns (laminae VII and VIII) (Fig. 2). Groupings of neurons were apparent in medial areas of gray matter of lower (L5–7) lumbar segments, although cells could also be seen at more lateral locations in these segments. At more rostral locations, cells in the intermediate zone were more spread out, blending into lamina VIII of the ventral horn. As described before (Dai et al. 2005), labeling of the motor nuclei was rare, indicating that most motoneurons do not express Fos in response to repetitive activation in this model. Noradrenergic immunoreactive boutons innervated (Fig. 1, A–C) the majority (∼60–100%) of Fos immunoreactive spinal neurons (Fig. 3A), with no obvious trends throughout the thoraco-lumbar segments. The average number of Fos labeled cells/section in close contact with noradrenergic fibers (calculated from 18 sections from each segment) increased with locomotor activity (Fig. 3B). The average number of innervated cells per section was highest in mid/low lumbar segments (10 to 11 cells/section) and decreased rostrally. Expressed as a percentage, the amount of innervated Fos labeled neurons/section from the T13-L7 segments (listed respectively) of each locomotor animal increased substantially in comparison with the control: LC1: 179%, 600%, 244%, 338%, 288%, 249%, 442%, and 197%; LC2: 464%, 393%, 200%, 375%, 359%, 173%, 596%, and 263%. The ANOVA demonstrated that the number of innervated cells per section was significantly different between control and locomotor cats. F-values ranged between 12.0 for L3 to 29.7 for L6 and were all highly significant (P < 0.000). A Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that the number of innervated cells per section was significantly greater in locomotor animals than in the control animals in all but one segment (T13 of LC1) (Fig. 3B). Taking the length of each individual segment into consideration (7–15 mm), the average number of innervated cells per section and a section thickness of 30 μm, we estimated that the overall number of contacted Fos cells within the T13-L7 segments of locomotor animals ranged between ∼900 and 3,400 neurons/segment (Fig. 3C), with highest values in midlumbar segments.

The laminar distributions of noradrenergic innervated neurons within the different segments from both locomotor and control animals are plotted in Fig. 3, D–F. In locomotor animals, the largest number of innervated cells was found in lamina VII, with peak values in the L5 and L6 lumbar segments for LC1 and LC2, respectively. An ANOVA demonstrated that the number of innervated cells per section in lamina VII was significantly different between control and locomotor cats. F-values ranged between 8.0 for L2 to 22.4 for L1 and were all highly significant (P < 0.000 for all but L2, which was significant at P < 0.001). A subsequent Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that the number of lamina VII innervated cells per section in each locomotor cat was significantly greater than control in all segments (Table 1) but usually not significantly different from each other. Increased numbers of innervated Fos labeled neurons were also found in other laminae of locomotor animals compared with control but were most consistent for lamina VIII. An ANOVA revealed significant differences in L3–6 lumbar segments. F-values ranged between 4.0 for L4 to 6.9 for L5 (P < 0.05 to P < 0.01). Bonferroni post hoc analyses revealed significantly more innervated lamina VIII neurons in the L3, 5, and 6 segments for LC1 and in L3 and four segments of LC2 compared with that seen in the control (Table 2). No significant differences between locomotor animals were observed for the number of innervated lamina VIII cells per section. Fos labeling of neurons within the dorsal horn neurons was generally higher in LC2 but not consistent in LC1. The labeling appeared to be somewhat weaker, however, and may have been related to the slight movements observed during MLR stimulation in both locomotor animals when the paralytic temporarily wore off (see Noga et al. 2009).

Table 1.

Multiple comparisons-number DβH innervated Fos cells/section: lamina VII

| Segment | Control (n = 18) | LC1 (n = 18) | LC2 (n = 18) | ANOVA F statistic, P value | Control vs. LC1* | Control vs. LC2* | LC1 vs. LC2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T13 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 1.72 ± 1.73 | 3.11 ± 2.27 | 15.1, P < 0.000 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.05 |

| L1 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 3.94 ± 2.61 | 2.78 ± 1.52 | 22.4, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | ns |

| L2 | 0.28 ± 0.46 | 3.44 ± 3.69 | 3.28 ± 2.63 | 8.0, P < 0.001 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | ns |

| L3 | 0.28 ± 0.57 | 3.67 ± 2.65 | 3.00 ± 2.17 | 14.0, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.001 | ns |

| L4 | 0.56 ± 0.78 | 4.56 ± 2.59 | 3.67 ± 2.72 | 15.8, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | ns |

| L5 | 1.28 ± 0.83 | 5.94 ± 2.88 | 3.78 ± 2.60 | 18.2, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.05 |

| L6 | 0.44 ± 0.62 | 5.33 ± 3.42 | 5.00 ± 2.66 | 20.4, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | ns |

| L7 | 1.11 ± 0.96 | 4.11 ± 2.69 | 2.47 ± 2.03 (n = 15) | 9.2, P < 0.000 | P < 0.000 | P < 0.05 | ns |

Values are means ± SD; ANOVA: F and P values;

Bonferroni corrected post hoc comparisons; ns, not significant.

Table 2.

Multiple comparisons - number DβH innervated Fos cells/section: lamina VIII

| Segment | Control (n = 18) | LC1 (n = 18) | LC2 (n = 18) | ANOVA F statistic, P value | Control vs. LC1* | Control vs. LC2* | LC1 vs. LC2* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T13 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.17 ± 0.51 | 0.44 ± 0.62 | 3.1, ns | na | na | na |

| L1 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.50 ± 0.62 | 0.44 ± 0.98 | 3.0, ns | na | na | na |

| L2 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.44 ± 0.98 | 0.44 ± 0.70 | 1.7, ns | na | na | na |

| L3 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.89 ± 0.96 | 0.72 ± 0.96 | 5.5, P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.05 | ns |

| L4 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.17 ± 0.38 | 0.50 ± 0.86 | 4.0, P < 0.05 | ns | P < 0.05 | ns |

| L5 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.61 ± 2.20 | 0.56 ± 0.62 | 6.9, P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | ns | ns |

| L6 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.78 ± 1.00 | 0.44 ± 0.70 | 5.5, P < 0.01 | P < 0.01 | ns | ns |

| L7 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.78 ± 1.06 | 0.53 ± 1.13 (n = 15) | 3.2, ns | na | na | na |

Values are means ± SD; ANOVA: F and P values;

Bonferroni corrected post hoc comparisons; na, not applicable.

NEα1A Receptor/Fos Immunohistochemistry and Colocalization

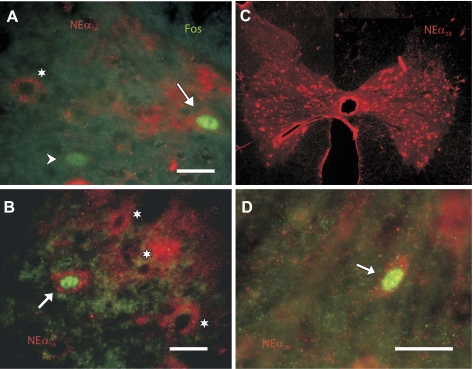

NEα1A receptors were colocalized with neurons staining positive for Fos (Fig. 4, A and B). Receptor staining was spread diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of soma and proximal dendrites (at or near the surface and intracellularly) and was not observed within the nucleus. The occurrence and location of double-stained neurons was documented for multiple sections from thoraco-lumbar segments of LC1 and 2. Figure 5A illustrates the maps of NEα1A/Fos labeled neurons for LC1. Double-labeled neurons were observed primarily in lamina VII and occasionally in laminae VIII and X. Approximately a quarter of the total number of Fos labeled neurons (from all laminae) showed colocalization (24.1 ± 7.6%, mean ± SD; range ∼10–40%) with no obvious rostrocaudal distribution (Fig. 5B). Similarly, low percentages of double-labeled cells were observed in LC2 (Fig. 5B). Plots of the laminar distributions of Fos stained neurons with and without NEα1A immunoreactivity (Fig. 5, C and D) also indicate that the majority of double-labeled cells are found in lamina VII. Double-labeled neurons comprised 27% and 34% of the total number of lamina VII Fos labeled cells from lumbar and thoracic segments of LC1, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Adrenergic NEα1A and NEα2B receptor localization in the lumbar spinal cord. Representative immunocytochemical images of locomotor-activated neurons identified by Fos nuclear labeling (green) with (arrows) or without (arrowhead) colocalized NEα1A (A and B) and NEα2B (D) receptors (red). Cells staining for receptor or Fos alone are indicated by asterisks or arrowheads, respectively. All cells are located in lamina VII of T10 (A), T12 (B), and L3 (D) thoraco-lumbar segments. Photomontage of NEα2B receptor stained neurons from a single section of the L3 lumbar segment of LC1 is shown (C). Immunoreactive neurons are localized primarily to intermediate zone and ventral horn locations. Confocal images are in A and B (optical slices); fluorescence microscopic images are in C and D. Scale bars: 20 μm in A, B, and D.

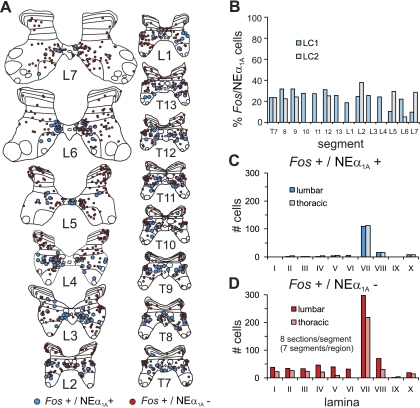

Fig. 5.

Segmental and laminar distribution of NEα1A labeled locomotor-activated neurons. Maps of Fos immunoreactive neurons colocalized with or without NEα1A receptors from the T7-L7 thoraco-lumbar segments of locomotor cat LC1 are shown in A. Fos positive cells with NEα1A receptors are indicated with blue circles; those without receptors are indicated with red circles. Each diagram includes all labeled cells from 8 sections of that segment. The percentage of Fos labeled cells colocalizing NEα1A receptors for the different segments of LC1 is plotted in B (blue bars). Percentages from 8 measured segments of LC2 (gray bars) are also plotted. The percentage varied between ∼10% and 40% (24.1 ± 7.6%, mean ± SD) without any apparent rostro-caudal distribution. The laminar distribution of double-labeled and Fos-labeled cells without NEα1A receptors from LC1 is illustrated in C and D, respectively. Data are categorized into lumbar and thoracic regions. Largest numbers of cells of both types were found in lamina VII in thoracic and lumbar regions.

NEα2B Receptor/Fos Immunohistochemistry and Colocalization

Sections from thoraco-lumbar segments (T7-L7) of LC1 were processed for Fos and NEα2B receptor immunoreactivity (Fig. 4, C and D). In reconstructed whole sections of spinal cord, numerous labeled neurons were observed in ventral laminae (V-X) rather than more dorsal laminae (I-IV), although this was not quantified. Receptor staining was spread diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of the soma and could be seen to extend into the proximal dendrites (as observed for NEα1A receptors), especially in larger cells. In contrast with that observed for NEα1A receptors, most Fos immunoreactive cells were positive for the receptor (Fig. 6A). Approximately 70–90% (77.8 ± 8.0%, mean ± SD) of all locomotor activated neurons showed colocalization, with no obvious trends in rostrocaudal distribution (Fig. 6B). Similar percentages of double-labeled cells were observed in segments examined for LC2 (Fig. 6B). Laminar distributions are illustrated in Fig. 6, C and D. The majority of double-labeled cells in thoracic and lumbar segments were found in laminae VII, comprising 88% and 86% of the total number of lamina VII Fos labeled cells in those segments, respectively. A large percentage of Fos labeled neurons in lamina VIII and X of thoracic and lumbar neurons were also double-labeled (88% and 90% for lamina VIII and 59% and 76% for lamina X thoracic and lumbar segments, respectively).

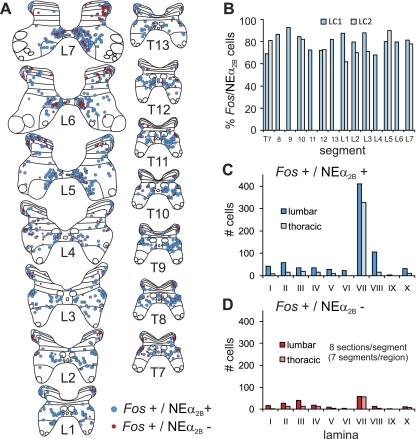

Fig. 6.

Segmental and laminar distribution of NEα2B immunoreactive locomotor-activated neurons. Maps of Fos immunoreactive neurons colocalized with or without NEα2B receptors from the T7-L7 thoraco-lumbar segments of locomotor cat LC-1 are shown in A. Fos positive cells labeled with or without NEα2B receptors are indicated with blue and red circles, respectively. Each diagram includes all labeled cells from 8 sections of that segment. The percentage of Fos-labeled cells colocalizing NEα2B receptors for different segments of LC1 (blue bars) and LC2 (gray bars) is plotted in B. Note that the percentage ranged between ∼70% and 90% (77.8 ± 8.0%, mean ± SD), without any apparent rostro-caudal distribution. The laminar distribution of double-labeled and Fos-labeled cells without NEα2B receptors is illustrated in C and D, respectively. Data are categorized into lumbar and thoracic regions, with an equal number of sections and segments for each category. Largest numbers of cells of both types were found in lamina VII.

Comparison Between Noradrenergic and Serotonergic Innervation/Receptor Colocalization

The tissue obtained in the present study was derived from the same animals used in our previous publication (Noga et al. 2009), allowing us to make statistical comparisons on the same animals using paired samples t-tests. Comparisons of noradrenergic and serotonergic innervation of locomotor-activated neurons (from thoracolumbar segments T13-L7) are illustrated in Fig. 7. In general, a significantly lower percentage of Fos labeled cells were innervated by noradrenergic than serotonergic fibers in nearly all segments examined. The average number of noradrenergic innervated Fos cells per section found in either all laminae, in lamina VII, or in lamina VIII (Fig. 7, B–D, respectively) was also generally lower than the number of serotonergic innervated cells in the corresponding laminae. Significant differences were noted for select segments (L3, L4, L6, and L7 for all laminae; L7 for lamina VII; and L3, L4, and L6 for lamina VIII). Statistical comparisons of noradrenergic (NEα1A and NEα2B) and serotonergic (5-HT7, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT1A) receptor colocalization (Noga et al. 2009) of locomotor-activated neurons are illustrated in Fig. 8. In this analysis, we examined LC1 since only this animal afforded the most complete evaluation of all segments and receptor subtypes examined in this and our previous study (Noga et al. 2009) and since the percentages of colocalization of receptors are similar for both locomotor animals in those segments for which this was examined (Figs. 5 and 6 in this study and Fig. 8 in Noga et al. 2009). The percentage of Fos cells (mean ± SD) colocalized with the different monoaminergic receptors in each of the segments of the thoracic (T7–13), lumbar (L1-L7), or thoracolumbar (T13-L7) regions is shown in Fig. 8A. Comparison of lumbar and thoracic regions within each receptor group indicated that there was a significantly higher percentage of 5-HT7 receptor labeling in the lumbar cord than in the thoracic cord as described previously (Noga et al. 2009). The reverse was true for NEα1A receptors. In the lumbar cord, a significantly higher percentage of Fos labeled cells colocalized NEα2B, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT7 receptors than 5-HT1A receptors, with the least significant being NEα1A receptors. A similar order was observed for the thoracolumbar cord segments. Comparisons between the average number (means ± SD) of Fos cells in 8 sections per segment in the indicated spinal regions colocalized with each receptor for lamina VII are shown in B. Comparison of lumbar and thoracic regions within each receptor group indicated that there was a significantly higher number of 5-HT7 and NEα2B receptor labeling in lamina VII of the lumbar cord than in the thoracic cord. In lamina VII of the lumbar segments, the monoaminergic receptor subtype colocalization examined statistically fell into the following order: NEα2B = 5-HT2A ≥ 5-HT7 = 5-HT1A > NEα1A. A similar order was observed for the thoracolumbar region: NEα2B = 5-HT2A > 5-HT7 > NEα1A (no thoracic region samples were analyzed for the 5-HT1A receptor).

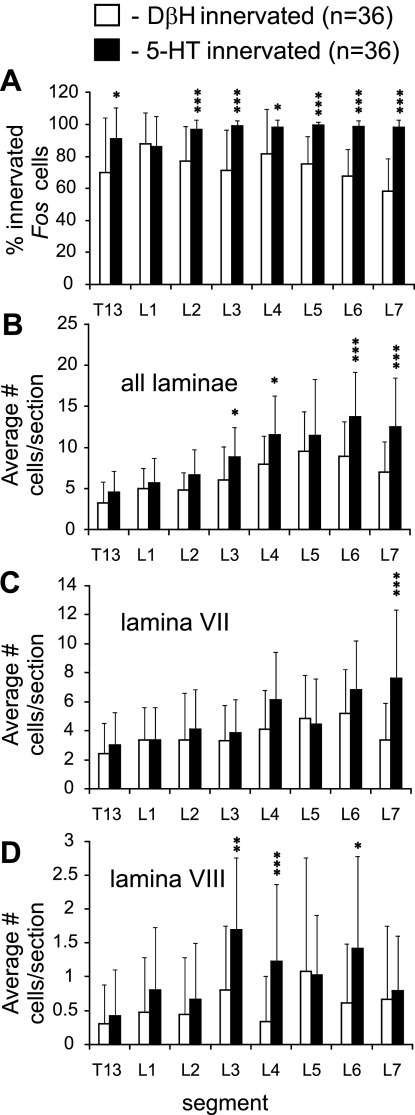

Fig. 7.

Statistical comparisons of noradrenergic and serotonergic innervation (Noga et al. 2009) of locomotor-activated neurons. Eighteen sections from each locomotor animal LC1 and LC2 were grouped together for each of the thoracolumbar (T13-L7) segments (for a total of 36 measures) and comparisons (paired samples T tests, with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons) made between NE innervated and 5-HT innervated groups. The percentage of noradrenergic and serotonergic innervated Fos cells for each segment (mean ± SD) of locomotor animals grouped together is compared in A. In nearly all segments, a significantly larger percentage of Fos cells were innervated by serotonergic fibers. Comparisons between the average number (mean ± SD) of noradrenergic and serotonergic innervated cells/section for all laminae, lamina VII, and lamina VIII are shown in B, C, and D, respectively. In general, serotonergic innervation was more predominant in all segments examined and significantly greater than noradrenergic innervation in select segments (L3, L4, L6, and L7 for all laminae; L7 for lamina VII; and, L3, L4, and L6 for lamina VIII). Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

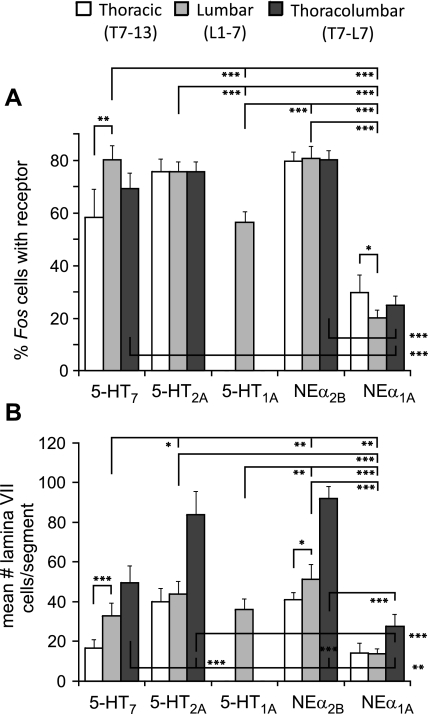

Fig. 8.

Statistical comparisons of noradrenergic and serotonergic receptor colocalization (Noga et al. 2009) of locomotor-activated neurons. Eight sections from each segment of the thoracolumbar spinal cord were grouped together into thoracic (T7–13), lumbar (L1-L7), or thoracolumbar (T7-L7) regions and comparisons (paired samples T tests, with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons) made for each of the serotonergic (5-HT7, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT1A) and noradrenergic (NEα1A and NEα2B) receptors for LC1. Comparisons of the percentage of Fos cells (mean ± SD) with the different receptors in each of the regions are shown in A. Comparisons between the average number (mean ± SD) of Fos cells per segment colocalized with each receptor for lamina VII are shown in B. Only statistically significant differences are indicated. Significance levels: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that most locomotor-activated neurons in the thoraco-lumbar spinal cord of the cat are innervated by descending noradrenergic fibers and that many of these neurons are immunoreactive for subtypes (NEα1A and NEα2B) of two of the major noradrenergic receptor classes implicated in the control of locomotion. The study thus provides an anatomical basis at the spinal level for the noradrenergic activation/modulation of locomotion as documented for intact, acute, or chronically spinalized cats (Barbeau and Rossignol 1991; Barbeau et al. 1987; Chau et al. 1998; Giroux et al. 2001; Kiehn et al. 1992; Marcoux and Rossignol 2000), rabbits (Viala and Buser 1969), adult rats (Majczyński et al. 2006), and the neonatal rodent (Gordon and Whelan 2006; Kiehn et al. 1999; Sqalli-Houssaini and Cazalets 2000; Taylor et al. 1994). The importance of this fact is underscored by the observations that: 1) cells in the locus ceruleus, subceruleus, and Kölliker-Fuse nuclei receive afferent projections from the MLR or its anatomical equivalent (Edwards 1975; Sotnichenko 1986; Steeves and Jordan 1984) and 2) noradrenergic neurons in the locus ceruleus increase their activity and may become rhythmically active during locomotion (Rasmussen et al. 1986). Taken together with our preliminary observations that stimulation of the MLR increases activity-dependent labeling of noradrenergic brainstem neurons (Noga et al. 2008) and modulates the spinal release of NE during locomotion (Noga et al. 2006, 2007), the results of the present study are consistent with the idea of a noradrenergic component to the central pathways controlling locomotor activity (Hägglund et al. 2010; Noga et al. 1988, 1991, 2003, 2009).

Segmental and Laminar Distribution of Noradrenergic Innervated Locomotor-Activated Neurons

Most (60–100%) Fos positive spinal neurons from the thoraco-lumbar (T13-L7) segments (located primarily in laminae VII and VIII) were contacted by noradrenergic immunoreactive terminals (Figs. 3A). This distribution is consistent with the ubiquitous nature of the noradrenergic innervation of the spinal cord. Descending noradrenergic terminals are distributed to all levels of the spinal cord and, although terminating throughout the spinal gray matter, they densely innervate neurons in the medial part of laminae VII and VIII as well as neurons in the intermediolateral cell column and lamina X (Clark and Proudfit 1991; Fuxe et al. 1990; Grzanna and Fritschy 1991; Rajaofetra et al. 1992). The similar segmental and laminar distribution of noradrenergic (Fig 3, B and C) and serotonergic innervated locomotor neurons (Noga et al. 2009) reaffirms the idea that these cells are involved in the central generation of locomotion in the cat (Dai et al. 2005; Noga et al. 1995). This idea is supported by observations that: 1) MLR stimulation evokes the largest field potentials within laminae VII and VIII of the L4-L6 segments (Noga et al. 1995); 2) spinal lesions below caudal L5 (Grillner and Zangger 1979) or within L3 or L4 (Langlet et al. 2005; Marcoux and Rossignol 2000) abolish locomotor capabilities in spinal animals; 3) injections of clonidine and yohimbine into the L3-L6 segments are sufficient to induce or block spontaneous/sensory-evoked walking, respectively (Delivet-Mongrain et al. 2008; Marcoux and Rossignol 2000); and 4) the midlumbar segments are the leading ones for the production of rhythmic oscillations in the cat (Deliagina et al. 1983).

Significant numbers of locomotor-activated neurons in laminae VII and VIII of rostral lumbar and caudal thoracic segments are also contacted by noradrenergic fibers and/or colocalize NEα1A and NEα2B receptors (Figs. 2, 5, 6). These data, along with similar data demonstrating serotonergic innervation and receptor colocalization in these locations (Noga et al. 2009), affirm the distributed nature of locomotor networks described for both cat (Dai et al. 2005; Noga et al. 2009) and rat (Cazalets et al. 1995; Cowley and Schmidt 1997; Kjaerulff and Kiehn 1996). In the high decerebrate cat, injections of the NEα2 noradrenergic antagonist yohimbine into individual thoracolumbar segments T10-L2 will block spontaneous treadmill locomotion (Delivet-Mongrain et al. 2008) although locomotor activity can still be evoked by exteroceptive stimulation. There is preliminary evidence that neurons in these locations of the cat are also sensitive to 5-HT via action at 5-HT7 receptors (Schmidt and Jordan 2000) similar to that observed in the rodent (Liu and Jordan 2005; Liu et al. 2009). Because most locomotor neurons in these areas colocalize 5-HT7 or 5-HT2A receptors (Noga et al. 2009), it is likely that both 5-HT and NE modulate the activity of the same cells (see Functional considerations below).

Candidate Neuronal Populations Innervated by Noradrenergic Fibers

The use of Fos expression as an activity-dependent marker for visualization of large populations of functionally related, locomotor-activated neurons has been discussed previously (Dai et al. 2003). Some populations of neurons do not express Fos following somatosensory stimulation (Strassman et al. 1993) nor under the experimental conditions used in the present study, indicating that caution is warranted for the interpretation of negative results. In the paralyzed artificially ventilated animal, Fos is not expressed in alpha motoneurons—which require additional loading of hindlimb muscles (Omori et al. 2005), nor in Clarke's Column where dorsospinocerebellar neurons are located—as would be expected if their rhythmicity depended upon intact afferent inflow from the moving limb (Poppele et al. 2003). Despite this, many candidate interneuronal populations fit with the overall pattern of Fos expression observed following locomotor induction seen in this and other studies (Dai et al. 2003, Huang et al. 2000; Noga et al. 2009). Additional candidate interneuronal populations to those already described (Dai et al. 2003) include: 1) Hb9 neurons (Wilson et al. 2005), located in medial lamina VIII/ventral lamina X; 2) V0 cells of lamina VIII (Lanuza et al. 2004), which express Fos following drug-induced locomotion; and 3) cholinergic interneurons (Zagoraiou et al. 2009), which may be a subset of the neurons observed previously (Huang et al. 2000). Further study is warranted to determine whether any of these neuronal groups are present in the cat spinal cord and, if so, whether they are innervated by noradrenergic terminals and/or possess NE receptors.

Nature of Noradrenergic Contacts on Locomotor-Activated Neurons.

The terminals of noradrenergic axons were often seen in clusters, coursing across the soma and proximal dendrites of locomotor-activated neurons with multiple boutons/fiber in close proximity to their surface (Fig. 1). Although we did not determine whether these contacts were synaptic, they are close enough to influence the neurons via volume transmission (Agnati et al. 1995) (see introduction). Both synaptic and nonsynaptic noradrenergic terminals have been described in dorsal horn (Doyle and Maxwell 1991, 1993; Hagihira et al. 1990; Rajaofetra et al. 1992; Ridet et al. 1993) and intermediate zone laminae of midlumbar segments (Hammar and Maxwell 2002), supporting this possibility.

Noradrenergic Receptor Subtypes of Locomotor-Activated Neurons

Staining for both NEα1A and NEα2B receptor subtypes was found diffusely throughout the cytoplasm of the soma and proximal dendrites (at or near the surface and intracellularly), indicating that the neurons make the protein. Intracellular labeling of many receptor proteins subtypes has been reported elsewhere (see Rosin et al. 1996), including NEα1A receptors in lumbar motoneurons (Tartas et al. 2010) and NEα2B receptors in spinal and hippocampal neurons (Patrick A. Carr, U. North Dakota, personal communication). The data are consistent with NEα1A and NEα2B receptor mRNA expression within the spinal cord (see below: Day et al. 1997; Smith et al. 1995). As discussed by Rosin et al. (1996), intracellular immunoreactivity could represent either a newly synthesized or posttranslationally modified receptor before its insertion in the plasmalemma or receptor that has been internalized for recycling or degradation. A more detailed ultrastructural analysis will be required to determine where the receptors are inserted into the membrane.

Spinal NEα1A receptors.

Approximately 10–40% of Fos immunoreactive neurons (localized primarily to lamina VII) colocalize the NEα1A receptor, with no obvious rostrocaudal gradient across the T7-L7 thoraco-lumbar cord. This distribution is consistent with quantitative ligand binding autoradiography in these areas using [3H]prazosin, a nonspecific NEα1 receptor antagonist (Giroux et al. 1999; Roudet et al. 1993; Wada et al. 1996). Of the various NEα1 receptor subtypes known (NEα1A, NEα1B and NEα1D: Calzada and De Artiñano 2001), the NEα1A receptor subtype comprises approximately 70% of the total population of NEα1 receptors in the dorsal and ventral horns (Wada et al. 1996). NEα1A receptor mRNA expression also predominates throughout the spinal cord (Day et al. 1997). In the lumbar cord, the strongest NEα1A receptor mRNA expression is found in laminae VIII and IX, with moderate labeling in laminae V-VII and X (Day et al. 1997). Because NEα1 receptor density increases following noradrenergic denervation of the spinal cord (Giroux et al. 1999; Roudet et al. 1993, 1995), a postsynaptic origin for this receptor is likely.

The localization of NEα1A receptor immunoreactivity to locomotor-activated neurons is in keeping with pharmacological studies indicating a role for NEα1 receptors in locomotor activity. Studies to date have used drugs that act nonselectively on the NEα1 receptor (Bylund et al. 2010). In the early spinal cat, intrathecal administration of methoxamine, a full agonist at NEα1A and NEα1D receptors, with about a 20-fold greater potency at the NEα1A subtype (Minneman et al. 1994) induces locomotion with good weight support and increased extensor output (Chau et al. 1998). The activity is blocked by prazosin, a NEα1 receptor inverse agonist (Bylund et al. 2010) with weaker antagonist action at NEα2B and NEα2C receptors (Marjamaki et al. 1993). In late spinal cats, methoxamine improves the regularity of stepping, interlimb coupling, and endurance and increases extensor output and duration (Brustein and Rossignol 1999; Chau et al. 1998). Although these later effects may be due, in part, to actions on motoneurons (Day et al. 1997; Giroux et al. 1999; Lee and Heckman 1999; see also Rank et al. 2011), it is likely that effects are also due to actions on spinal commissural and Ia inhibitory interneurons whose activation by Ia muscle afferents or reticulospinal inputs are well known to be modulated by NEα1 receptor agonists (Hammar and Jankowska 2003; Hammar et al. 2004, 2007). It is possible that some of the NEα1A immunoreactive neurons observed in mid- and caudal lumbar segments of the present study are part of these latter two groups of neurons. Both cell types are rhythmically active during MLR evoked fictive locomotion (Matsuyama et al. 2004; Noga et al. 1987). Furthermore, commissural neurons within L4/5 lumbar segments are activated by stimulation within the cuneiform nucleus and the MLR (Jankowska and Noga 1990; Matsuyama et al. 2004) possibly via activation of reticulospinal neurons (Bannatyne et al. 2003; Matsuyama et al. 2004; Noga et al. 1995, 2003).

Spinal NEα2B receptors.

The present study is the first to show NEα2B receptor expression in the lumbar spinal cord of the cat using immunohistochemical methods. The high degree of colocalization (70–90%) within functionally defined spinal locomotor activated neurons of laminae VII and VIII of thoraco-lumbar segments (Fig. 6, A and C) indicates that this receptor subtype may be important in the initiation and/or modulation of locomotion. Preliminary evidence obtained in our laboratory (unpublished results) using pharmacological antagonism of NEα2B receptors in the cat further supports this idea.

Early studies first identified NEα2 receptors as a class within the spinal cord of both cat and rat (e.g., Howe and Yaksh 1984; Simmons and Jones 1988) and indicated that most receptors are localized postsynaptically rather than on terminals of descending noradrenergic fibers (Giroux et al. 1999; Roudet et al. 1994) or primary sensory afferents (Howe et al. 1987). To date, studies examining the spinal location of NEα2 receptor subtypes (NEα2A/D, NEα2B, and NEα2C: Fairbanks et al. 2009) have only been reported for the rat and human. In the postnatal and adult rat, NEα2A and NEα2C receptor mRNAs are found in abundance in dorsal and ventral horn neurons, whereas very few neurons contain NEα2B mRNAs (Nicholas et al. 1993; Shi et al. 1999; Huang et al. 2002). Autoradiographic (Uhlén et al. 1997) and immunohistochemical (Rosin et al. 1996) studies generally support these results (Riedl et al. 2009; Stone et al. 1998). In contrast with the rat, postsynaptic NEα2A and NEα2B receptor mRNAs are found in abundance in the adult human spinal cord (Smith et al. 1995), whereas NEα2C mRNA levels are relatively low. In the lumbar cord, NEα2B receptor mRNA is observed in the superficial dorsal horn and especially in laminae V-X, a distribution that is consistent with their localization to locomotor-activated neurons observed in the present study (Fig. 4C).

Pharmacological locomotor studies, using drugs that act on the NEα2 receptor as a class (Bylund et al. 2010; Jasper et al. 1998), are in keeping with the proposed role of NEα2B receptors in locomotor activity. In the intact cat, intrathecal injection of clonidine at the midlumbar level decreases the step cycle duration and increases the regularity of stepping (Giroux et al. 2001), whereas yohimbine, the NEα2 antagonist, disrupts spontaneous locomotion. In the high decerebrate cat, microinjection of yohimbine into the L3 or L4 segments blocks spontaneous and exteroceptive-evoked treadmill locomotion (Delivet-Mongrain et al. 2008) and spontaneous locomotion when injected into the T10-L2 or L5–7 segments. Studies on spinal cats (Barbeau and Rossignol 1991; Barbeau et al. 1987; Chau et al. 1998; Giroux et al. 2001; Marcoux and Rossignol 2000) also demonstrate a potential role for NEα2 receptors in the control of locomotor activity at all stages of injury (acute through chronic) as would be expected from the continued presence of the receptors following chronic spinal transection (Giroux et al. 1999). Although the effects of some noradrenergic drugs may be due to direct effects on motoneuron excitability (Tremblay and Bedard 1986), it is most likely that the induction and modulation of ongoing locomotor activity by NEα2 receptor drugs are due to action on postsynaptic receptors on pattern generating neurons in mid-to-caudal lumbar segments. Pharmacological studies in rats, which lack NEα2B receptors, have revealed differences in the locomotor initiating capabilities of NE and its various receptor agonists. In the in vitro neonatal rat, NE evokes only nonlocomotor rhythmic activity (Gabbay and Lev-Tov 2004; Kiehn et al. 1999; Sqalli-Houssaini and Cazalets 2000), which is mimicked by NEα1, but not NEα2, receptor agonists. However, NE may modulate ongoing or spontaneous locomotor activity, speeding up the rhythm by NEα1 receptor agonists and slowing down the rhythm by NEα2 agonists that are more selective for NEα2A receptors (Sqalli-Houssaini and Cazalets 2000; see also Gordon and Whelan 2006). In contrast, administration of the noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and adrenergic precursor L-DOPA initiates and/or facilitates locomotion in intact and spinal rats (Navarrete et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 1994). Conversely, intrathecal administration of yohimbine impairs spontaneous hindlimb locomotor activity in intact rats, leading to trunk instability or total paralysis (Majczyński et al. 2006). Whether this effect is due to action at NEα2 receptors or 5-HT1A receptors (Bylund et al. 2010), which are also found on locomotor-activated neurons (Noga et al. 2009), is unclear.

Functional Considerations

Multiplicity of monoaminergic innervation/receptor localization on locomotor neurons: implications for control of spinal function.

The majority of locomotor-activated neurons seen in this and our previous study (Noga et al. 2009) are innervated by noradrenergic and serotonergic fibers. Convergent serotonergic and noradrenergic innervation has been described previously for premotor group II interneurons, commissural interneurons, and ventral spinocerebellar tract neurons in the midlumbar segments of the cat (Hammar and Maxwell 2002; Hammar et al. 2004; Maxwell et al. 2000). Close appositions are observed across the whole surface of these neurons, but the contacts may be differentially distributed, with highest percentages of such appositions on proximal dendrites and with the total number of serotonergic contacts often far exceeding noradrenergic contacts at the level of the soma. This may explain our observation that significantly fewer Fos cells are innervated by noradrenergic than serotonergic fibers. Nevertheless, the high rates of serotonergic and noradrenergic innervation and NEα2B, 5-HT7, and 5-HT2A receptor expression (Noga et al. 2009) indicate that locomotor-activated neurons likely possess multiple monoaminergic receptor subtypes and allow us to predict that many lamina VII or VIII neurons will express all or some combination of these receptors. A multiple receptor expression may even include those receptors observed at lower frequencies in locomotor populations, such as NEα1A and 5-HT1A (Noga et al. 2009). Interestingly, both NEα1 and 5-HT2 receptor agonists have similar actions on afferent evoked locomotor activity (significantly decrease the frequency and increase the duration of the burst) in the neonatal mouse (Gordon and Whelan 2006). Quipazine (a 5-HT2 receptor agonist) may also enhance locomotor-like movements induced by l-DOPA (Guertin 2004; Landry and Guertin 2004; McEwen et al. 1997), and synergistic locomotor effects with 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A/7 receptor agonists have also been reported (Courtine et al. 2009). Spinal-level interactions on the same neurons may also explain why combining clonidine with cyproheptadine (a mixed antagonist with action at 5-HT2A/C receptors) synergistically enhances locomotion in persons with chronic incomplete spinal cord injury (Fung et al. 1990).

Both similar and opposing effects of NE or 5-HT receptor agonists on the responses of identified neurons to either segmental or descending inputs have been reported (Bras et al. 1990; Hammar and Jankowska 2003; Hammar et al. 2004, 2007; Jankowska et al. 2000). Postsynaptically, the net effect of transmitter action is likely to depend on the receptor subtype affinities, the overall type and number of bound receptor, and the G proteins expressed since transduction mechanisms for the receptor subtypes are multiple, often differ, and may be opposing or complementary to each other (Bylund et al. 2010; Raymond et al. 2001). Selectivity of action would be greater in instances where receptor subtypes were few, spatially compartmentalized to match specific afferent terminations, where neurotransmission was confined to the synaptic cleft and if there were physical or functional compartmentalization of the signaling components into microdomains (Raymond et al. 2001). Under conditions of diffuse extracellular monoaminergic neurotransmission (see introduction) control of spinal neuronal excitability and responsiveness in cells with multiple receptor subtypes would be dependent upon transmitter concentrations and receptor affinity. Low transmitter concentrations would be selective for higher affinity receptors such as NEα2B, NEα2A, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT7 and less so for lower affinity receptors such as NEα1A and 5-HT2A (Bylund et al. 2010, Martin et al. 2010). Selection of neuronal response would then depend upon the dynamic regulation of transmitter levels both temporally and spatially. Although the diffuse nature of the monoaminergic system has been considered a shortcoming of descending control of sensorimotor systems (e.g., Heckman et al. 2008), relatively high extracellular concentrations of monoamines are observed in well defined loci of the spinal cord during some steady state conditions (Noga et al. 2004), so it is possible that the activity of some neurons may be independently modulated. In this way, the monoaminergic system may be flexible, allowing for both broad-based and specific control of spinal neuronal pathways, depending upon behavioral state and functional requirements (Noga et al. 2007; Xie et al. 2009).

Human studies/clinical significance.

In spinally injured human, the response to nonselective noradrenergic drugs is variable (Dietz et al. 1995; Norman and Barbeau 1993; Norman et al. 1998; Rémy-Néris et al. 1999, 2003; Stewart et al. 1991) and depends upon the degree and level of spinal cord injury (SCI) and upon complex interactions or influences from surviving monoaminergic neurons (Brustein and Rossignol 1999; Fung et al. 1990; McEwen et al.1997; Shapiro 1997; Wiesendanger et al. 1984). This variability probably stems from changes in receptor expression (density, distribution, and binding affinity) (Gao and Ziskind-Conhaim 1993; Roudet et al. 1994), intrinsic receptor activity (Murray et al. 2010; Rank et al. 2011), and in properties of pattern generating neurons, which may have altered sensitivity to monoamines (Norreel et al. 2003). Success with pharmacological treatments will ultimately depend upon the balance of excitation and inhibition of spinal neurons/circuits that either facilitate or interfere with pattern generation and expression as studied by others (e.g., Edgerton et al. 2008; Van de Crommert et al. 1998). Ideally, pharmacological strategies should incorporate postsynaptic facilitation of locomotor generating neurons without excessively diminishing afferent facilitation. The identification of NEα2B receptors on functionally identified, locomotor-activated neurons in the present study provides a potential functional basis for selective pharmacological targeting of postsynaptic (NEα2B) and presynaptic (NEα2A) mechanisms in spinally injured human. This possibility is in keeping with the demonstration of NEα2B receptor mRNA expression in human lumbar spinal cord (Smith et al. 1995) and the fact that NEα2 receptor binding densities return to near control values in chronic spinal transection injuries (Giroux et al. 1999).

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS-46404, the State of Florida, and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Frydel for assistance in the use of StereoInvestigator and Neurolucida, Dr. E. Widerström-Noga for statistical analysis, A. Blythe and F. Sanchez for graphics assistance, and Dr. I. D. Hentall for comments on the article. Current address for D. M. G. Johnson: National Institute of Mental Health, 10 Center Dr., Bethesda, MD 20892. Current address for A. Pinzon: Department of Pediatrics, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136.

REFERENCES

- Agnati LF, Zoli M, Strömberg I, Fuxe K. Intercellular communication in the brain: wiring versus volume transmission. Neurosci 69: 711–726, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez FJ, Pearson JC, Harrington D, Dewey D, Torbeck L, Fyffe REW. Distribution of 5-hydroxytryptamine-immunoreactive boutons on α-motoneurons in the lumbar spinal cord of adult cats. J Comp Neurol 393: 69–83, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannatyne BA, Edgley SA, Hammar I, Jankowska E, Maxwell DJ. Networks of inhibitory and excitatory commissural interneurons mediating crossed reticulospinal actions. Eur J Neurosci 18: 2273–2284, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau H, Julien C, Rossignol S. The effects of clonidine and yohimbine on locomotion and cutaneous reflexes in the adult chronic spinal cat. Brain Res 437: 83–96, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau H, Rossignol S. Initiation and modulation of the locomotor pattern in the adult chronic spinal cat by noradrenergic, serotonergic and dopaminergic drugs. Brain Res 546: 250–260, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Cazalets JR. The respective contribution of lumbar segments to the generation of locomotion in the isolated spinal cord of newborn rat. Eur J Neurosci 16: 1741–1750, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras H, Jankowska E, Noga B, Skoog B. Comparison of effects of various types of NA and 5-HT agonists on transmission from group II muscle afferents in the cat. Eur J Neurosci 2: 1029–1039, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustein E, Rossignol S. Recovery of locomotion after ventral and ventrolateral spinal lesions in the cat. II. Effects of noradrenergic and serotonergic drugs. J Neurophysiol 81: 1513–1530, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Bond RA, Eikenburg DC, Hieble JP, Hills R, Minneman KP, Parra S.Adrenoceptors. (Online). http://www.iuphar-db.org/DATABASE/FamilyMenuForward?familyId=4 [15 Feb. 2010]

- Callado LF, Stamford JA. Spatiotemporal interaction of α2 autoreceptors and noradrenaline transporters in the rat locus coeruleus: implications for volume transmission. J Neurochem 74: 2350–2358, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada BC, De Artiñano AA. Alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes. Pharmacol Res 44: 195–208, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalets JR, Borde M, Clarac F. Localization and organization of the central pattern generator for hindlimb locomotion in newborn rat. J Neurosci 15: 4943–4951, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau C, Barbeau H, Rossignol S. Effects of intrathecal α.1- and α.2-noradrenergic agonists and norepinephrine on locomotion in chronic spinal cats. J Neurophysiol 79: 2941–2963, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark FM, Proudfit HK. The projection of noradrenergic neurons in the A7 catecholamine cell group to the spinal cord in the rat demonstrated by anterograde tracing combined with immunocytochemistry. Brain Res 547: 279–288, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Gerasimenko Y, Van Den Brand R, Yew A, Musienko P, Zhong H, Song B, Ao Y, Ichiyama RM, Lavrov I, Roy RR, Sofroniew MV, Edgerton VR. Transformation of nonfunctional spinal circuits into functional states after the loss of brain input. Nature Neurosci 12: 1333–1342, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. Regional distribution of the locomotor pattern generating network in the neonatal rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 77: 247–259, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Noga BR, Douglas JR, Jordan LM. Localization of spinal neurons activated during locomotion using the c-fos immunohistochemical method. J Neurophysiol 93: 3442–3452, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day HEW, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H. Distribution of α1a-, α1b- and α1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord. J Chem Neuroanat 13: 115–139, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deliagina TG, Orlovsky GN, Pavlova GA. The capacity for generation of rhythmic oscillations is distributed in the lumbosacral spinal cord of the cat. Exp Brain Res 53: 81–90, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delivet-Mongrain H, Leblond H, Rossignol S. Effects of localized intraspinal injections of a noradrenergic blocker on locomotion of high decerebrate cats. J Neurophysiol 100: 907–921, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Colombo G, Jensen L, Baumgartner L. Locomotor capacity of spinal cord in paraplegic patients. Ann Neurol 37: 574–582, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle CA, Maxwell DJ. Ultrastructural analysis of noradrenergic nerve terminals in the cat lumbosacral spinal dorsal horn: a dopamine-β-hydroxylase immunocytochemical study. Brain Res 563: 329–333, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle CA, Maxwell DJ. Direct catecholaminergic innervation of spinal dorsal horn neurons with axons ascending the dorsal columns in cat. J Comp Neurol 331: 434–444, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Courtine G, Gerasimenko YP, Lavrov I, Ichiyama RM, Fong AJ, Cai LL, Otoshi CK, Tillakaratne NJK, Burdick JW, Roy RR. Training locomotor networks. Brain Res Rev 57: 241–254, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SB. Autoradiographic studies of the projections of the midbrain reticular formation: descending projections of nucleus cuneiformis. J Comp Neurol 161: 341–358, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks CA, Stone LS, Wilcox GL. Pharmacological profiles of alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonists identified using genetically altered mice and isobolographic analysis. Pharmacol Ther 123: 224–238, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung J, Stewart JE, Barbeau H. The combined effects of clonidine and cyproheptadine with interactive training on the modulation of locomotion in spinal cord injured subjects. J Neurol Sci 100: 85–93, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, Tinner B, Bjelke B, Agnati LF, Verhofstad A, Steinbusch HGW, Goldstein M, Kalia M. Monoaminergic and peptidergic innervation of the intermedio-lateral horn of the spinal cord. I. Distribution patterns of nerve terminal network. Eur J Neurosci 2: 430–450, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay H, Lev-Tov A. Alpha-1 adrenoceptor agonists generate a “fast” NMDA receptor-independent motor rhythm in the neonatal rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 92: 997–1010, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao BX, Ziskind-Conhaim L. Development of chemosensitivity in serotonin-deficient spinal cords of rat embryos. Dev Biol 158: 79–89, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux N, Reader TA, Rossignol S. Comparison of the effects of intrathecal administration of clonidine and yohimbine on the locomotion of intact and spinal cats. J Neurophysiol 85: 2516–2536, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux N, Rossignol S, Reader TA. Autoradiographic study of α1- and α2-noradrenergic and serotonin1A receptors in the spinal cord of normal and chronically transected cats. J Comp Neurol 406: 402–414, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IT, Whelan PJ. Monoaminergic control of cauda-equina-evoked locomotion in the neonatal mouse spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 96: 3122–3129, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Zangger P. On the central generation of locomotion in the low spinal cat. Exp Brain Res 34: 241–261, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanna R, Fritschy JM. Efferent projections of different subpopulations of central noradrenaline neurons. Prog Brain Res, edited by Barnes CD, Pompeiano O. New York: Elsevier, 1991, p. 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin PA. Synergistic activation of the central pattern generator for locomotion by L-beta-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine and quipazine in adult paraplegic mice. Neurosci Lett 358: 71–74, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hägglund M, Borgius L, Dougherty KJ, Kiehn O. Activation of groups of excitatory neurons in the mammalian spinal cord or hindbrain evokes locomotion. Nature Neurosci 13: 246–252, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihira S, Senba E, Yoshida S, Tohyama M, Yoshiya I. Fine structure of noradrenergic terminals and their synapses in the rat spinal dorsal horn: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res 526: 73–80, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar I, Bannatyne BA, Maxwell DJ, Edgley SA, Jankowska E. The actions of monoamines and distribution of noradrenergic and serotonergic contacts on different subpopulations of commissural interneurons in the cat spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 19: 1305–1316, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar I, Jankowska E. Modulatory effects of α1-, α2-, and β-receptor agonists on feline spinal interneurons with monosynaptic input from group I muscle afferents. J Neurosci 23: 332–338, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar I, Maxwell DJ. Serotonergic and noradrenergic axons make contacts with neurons of the ventral spinocerebellar tract in the cat. J Comp Neurol 443: 310–319, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar I, Stecina K, Jankowska E. Differential modulation by monoamine membrane receptor agonists of reticulospinal input to lamina VIII feline spinal commissural interneurons. Eur J Neurosci 26: 1205–1212, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman BK. Immunofluorescence of dopamine-β-hydroxyase. Application of improved methodology to the localization of the peripheral and central noradrenergic nervous system. J Histochem Cytochem 21: 312–332, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman CJ, Hyngstrom AS, Johnson MD. Active properties of motoneurone dendrites: diffuse descending neuromodulation, focused local inhibition. J Physiol (Lond) 586.5: 1225–1231, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentall ID, Mesigil R, Pinzon A, Noga BR. Temporal and spatial profiles of pontine-evoked monoamine release in the rat's spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 89: 2943–2951, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdeen T, Leah JD. Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: control of gene expression by Jun, Fos, and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res Rev 28: 370–490, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe JR, Yaksh TL. [3H]ρ-aminoclonidine binding to multiple α2-adrenoceptor sites in homogenates of cat frontal cortex and cat spinal cord. Eur J Pharmacol 106: 547–559, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe JR, Yaksh TL, Go VLW. The effect of unilateral dorsal root ganglionectomies or ventral rhizotomies on α2-adrenoceptor binding to, and the substance P, enkephalin, and neurotensin content of, the cat lumbar spinal cord. Neurosci 21: 385–394, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A, Noga BR, Carr PA, Fedirchuk B, Jordan LM. Spinal cholinergic neurons activated during locomotion: localization and electrophysiological characterization. J Neurophysiol 83: 3537–3547, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Stamer WD, Anthony TL, Kumar DV, St. John PA, Regan JW. Expression of α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes in prenatal rat spinal cord. Dev Brain Res 133: 93–104, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Hammar I, Chojnicka B, Hedén CH. Effects of monoamines on interneurons in four spinal reflex pathways from group I and/or group II muscle afferents. Eur J Neurosci 12: 701–714, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Jukes MGM, Lund S, Lundberg A. The effect of DOPA on the spinal cord. VI. Half-centre organization of interneurons transmitting effects from the flexor reflex afferents. Acta Physiol Scand 70: 389–402, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Maxwell DJ, Dolk S, Dahlström A. A confocal and electron microscopic study of contacts between 5-HT fibres and dorsal horn interneurons in pathways from muscle afferents. J Comp Neurol 387: 430–438, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Maxwell DJ, Dolk S, Krutki P, Belichenko PV, Dahlström A. Contacts between serotoninergic fibres and dorsal horn spinocerebellar tract neurons in the cat and rat: a confocal microscopic study. Neurosci 67: 477–487, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Noga BR. Contralaterally projecting lamina VIII interneurons in middle lumbar segments in the cat. Brain Res 535: 327–330, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper JR, Lesnick JD, Chang LK, Yamanishi SS, Chang TK, Hsu SAO, Daunt DA, Bonhaus DW, Eglen RM. Ligand efficacy and potency at recombinant α2 adrenergic receptors. Agonist-mediated [35S]GTPγS binding. Biochem Pharmacol 55: 1035–1043, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DMG, Riesgo MI, Pinzon A, Noga BR. Monoaminergic innervation of locomotor activated cells in cat spinal cord. Soc Neurosci Abstr 65.15, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE, Friedman L. Atlas of catecholamine perikarya, varicosities and pathways in the brainstem of the cat. J Comp Neurol 215: 382–396, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Hultborn H, Conway BA. Spinal locomotor activity in acutely spinalized cats induced by intrathecal application of noradrenaline. Neurosci Lett 143: 243–246, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Sillar KT, Kjærulff O, McDearmid JR. Effects of noradrenaline on locomotor rhythm-generating networks in the isolated neonatal rat spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 82: 741–746, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff O, Kiehn O. Distribution of networks generating and coordinating locomotor activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: a lesion study. J Neurosci 16: 5777–5794, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry ES, Guertin PA. Differential effects of 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptor agonists on hindlimb movements in paraplegic mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 28: 1053–1060, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlet C, Leblond H, Rossignol S. Mid-lumbar segments are needed for the expression of locomotion in chronic spinal cats. J Neurophysiol 93: 2474–2488, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanuza GM, Gosgnach S, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Goulding M. Genetic identification of spinal interneurons that coordinate left-right locomotor activity necessary for walking movements. Neuron 42: 375–386, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Heckman CJ. Enhancement of bistability in spinal motoneurons in vivo by the noradrenergic α1 agonist methoxamine. J Neurophysiol 81: 2164–2174, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhao Z, Pan HL, Eisenach JC, Paqueron X. Norepinephrine release from spinal synaptosomes: auto-α2-adrenergic receptor modulation. Anesthesiol 93: 164–172, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Jordan LM. Stimulation of the parapyramidal region of the neonatal rat brain stem produces locomotor-like activity involving spinal 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A receptors. J Neurophysiol 94: 1392–1404, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Akay T, Hedlund PB, Pearson KG, Jordan LM. Spinal 5-HT7 receptors are critical for alternating activity during locomotion: in vitro neonatal and in vivo adult studies using 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice. J Neurophysiol 102: 337–348, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Pin C, Salvert D, Ligier M, Jouvet M. [Catecholamine containing neurons in the pontine tegmentum and their pathways in the cat.] Brain Res 57: 119–152, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majczyński H, Cabaj A, Slawińskiska U, Górska T. Intrathecal administration of yohimbine impairs locomotion in intact rats. Behav Brain Res 175: 315–322, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, Rossignol S. Initiating or blocking locomotion in spinal cats by applying noradrenergic drugs to restricted lumbar spinal segments. J Neurosci 20: 8577–8585, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjamaki A, Luomala K, Ala-Uotila S, Scheinin M. Use of recombinant human alpha 2-adrenoceptors to characterize subtype selectively of antagonist binding. Eur J Pharmacol 246: 219–226, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlier L, Sandillon F, Poulat P, Rajaofetra N, Geffard M, Privat A. Serotonergic innervation of the dorsal horn of rat spinal cord: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. J Neurocytol 20: 310–322, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR, Hoyer D, Andrade R, Barnes N, Baxter G, Bockaert J, Branchek T, Cohen ML, Dumuis A, Eglen RM, Göthert M, Hamblin M, Hamon M, Hartig PR, Hen R, Herrick-Davis K, Hills R, Humphrey PPA, Latté KP, Maroteaux L, Middlemiss DN, Mylecharane E, Peroutka SJ, Saxena PR, Sleight A, Villalon CM, Yocca F. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors (Online). http://www.iuphar-db.org/DATABASE/FamilyMenuForward?familyId=1 [15 Feb. 2010]

- Matsuyama K, Nakajima K, Mori F, Aoki M, Mori S. Lumbar commissural interneurons with reticulospinal inputs in the cat: morphology and discharge patterns during fictive locomotion. J Comp Neurol 474: 546–561, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell DJ, Riddell JS, Jankowska E. Serotonergic and noradrenergic axonal contacts associated with premotor interneurons in spinal pathways from group II muscle afferents. Eur J Neurosci 12: 1271–1280, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen ML, Van Hartesveldt C, Stehouwer DJ. l-DOPA and quipazine elicit air-stepping in neonatal rats with spinal cord transections. Behav Neurosci 111: 825–833, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minneman KP, Theroux TL, Hollinger S, Han C, Esbenshade TA. Selectivity of agonists for cloned α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Mol Pharmacol 46: 929–936, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]