Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important intra-neuronal signaling intermediates in angiotensin II (AngII)-related neuro-cardiovascular diseases associated with excessive sympathoexcitation, including hypertension and heart failure. ROS-sensitive effector mechanisms, such as modulation of ion channel activity, indicate that elevated levels of ROS increase neuronal activity. Nitric oxide, which may work to counter the effects of ROS, particularly superoxide, has been identified as a signaling molecule in angiotensin-1-7 (Ang-(1-7)) stimulated neurons. This review focuses on recent studies that have revealed details on the AngII-activated sources of ROS, the downstream redox-sensitive effectors, Ang-(1-7)-stimulated increase in nitric oxide, and the neuro-cardiovascular (patho)physiological responses modulated by these reactive species. Understanding these intra-neuronal signaling mechanisms should provide insight for the development of new redox-based therapeutics for the improved treatment of angiotensin-dependent neuro-cardiovascular diseases.

Introduction

Traditionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical are thought of as toxic by-products of cellular respiration. However, it is now well-accepted that these reactive species, primarily O2•− and H2O2, act as important intracellular signaling intermediates following stimulation of various plasma membrane receptors [1;2]. A collection of kinases, phosphatases, ion channels, and transcription factors among other cellular proteins have all been identified as redox-sensitive proteins [3]. Activation or inhibition of these signaling proteins by ROS, which can occur rapidly and transiently, suggests that cells and tissues can respond to small changes in the oxidative environment and do not need to be under “oxidative stress” for (patho)physiological responses to occur.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS), by acting on numerous organ systems, works to maintain cardiovascular and body fluid homeostasis. In central neurons, angiotensin II (AngII) activates the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) to induce a cascade of intra-neuronal signaling events that ultimately leads to changes in membrane potential and an increase in neuronal firing [4]. Activation of neurons in cardiovascular control brain regions, such as the subfornical organ (SFO), paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and rostral ventral lateral medulla (RVLM), results in stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, which mediates, at least in part, the cardiovascular complications associated with hypertension and heart failure [5;6]. Accumulating evidence over the past 8–10 years has established that AngII increases levels of ROS, particularly O2•−, in neurons which contribute to the increase in neuronal activation [7–13]; thus, identifying O2•− as a sympatho-excitatory molecule in the brain.

Although AngII is considered to be the primary effector peptide of the RAS, it is now appreciated that angiotensin-1-7 (Ang-(1-7)), which is generated by angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cleaving the carboxyl terminus phenylalanine residue from AngII, plays an important role in controlling cardiovascular function [14]. In the brain, Ang-(1-7) increases nitric oxide (NO•) levels via activation of the Mas receptor (MasR) and the angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R) [15;16]. NO• in the central nervous system (CNS) acts as a sympatho-inhibitory molecule [16;17]. Considering the reaction between O2•− and NO• is diffusion limited it is plausible that the balance between these two radicals is critical in the maintenance of sympathetic output. This review will focus on recent studies that have clarified the sources of O2•− in AngII-stimulated neurons, the downstream signaling mechanisms modulated by ROS, the counter-balance between the Ang-(1-7)-NO• and AngII-O2•− signaling pathways, and the neuro-cardiovascular responses mediated by these reactive species. In addition, the development of new redox-based therapeutics will be discussed.

Reactive oxygen species and AngII intra-neuronal signaling

The first evidence suggesting that ROS signaling in the brain contributes to the maintenance of sympathetic output came from studies where superoxide dismutase (SOD) protein microinjected into the RLVM of anesthetized pigs moderately decreased baseline sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) [18]. SOD, which catalyzes the dismutation of O2•− to H2O2 and oxygen, is endogenously expressed as three different proteins: 1) copper/zinc SOD (CuZnSOD or SOD1), which is primarily localized in the cytoplasm, but also present in the mitochondria [19]; 2) manganese SOD (MnSOD or SOD2), which is strictly expressed in mitochondria matrix; 3) extracellular SOD (ecSOD or SOD3), which, as its name suggests, is found extracellular. Previous studies have demonstrated that CuZnSOD or MnSOD overexpression in the SFO via adenoviral-mediated gene transfer virtually abolishes the central AngII-induced increase in MAP [11]. In addition, the characteristic dipsogenic response mediated by central AngII administration is significantly attenuated by overexpression of CuZnSOD or MnSOD [11]. These data indicate that intracellular O2•−, perhaps generated in both the cytosol and mitochondria, is a critical signaling molecule mediating the physiological responses of central AngII. Further studies using chronic hypertensive animal models, including slow-pressor AngII infusion [12] and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [20], and SOD overexpression in different cardiovascular control regions of the brain, including the SFO and RVLM, corroborate these initial findings. In addition, studies using models of chronic heart failure (CHF) where AngII signaling in the brain is elevated have shown that increased O2•− scavenging in the SFO, RVLM, and PVN attenuates the deleterious sympathoexcitation associated with this disease [21–24]. Suggesting a role for extracellular O2•−, Lob et al recently reported that deletion of ecSOD in the SFO augments the hypertensive response to peripheral AngII infusion [25]. Together, these studies indicate that O2•− signaling in the CNS mediates the AngII-induced increase in SNA and contributes to the pathogenesis of AngII-dependent neuro-cardiovascular disorders.

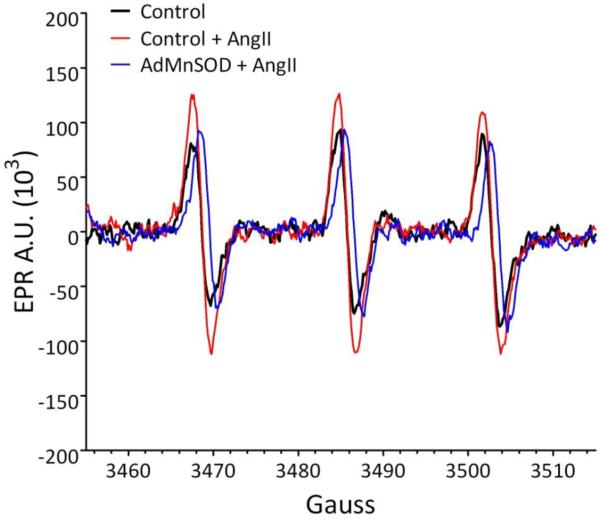

The obvious next question in this line of research was: What is/are the AngII-activated source(s) of O2•− in the CNS? Initial studies using non-specific inhibitors of NADPH oxidase, such as apocynin, diphenylene iodonium (DPI), and dominant-negative Rac1, indicated that, similar to peripheral cell types, NADPH oxidase is a primary source of O2•− in AngII-stimulated neurons [8;26;27]. A more recent study using siRNA technology and the silencing of specific NADPH oxidase (Nox) homologs not only confirmed the initial studies, but uncovered divergent roles for two of the Nox homologs – Nox2 and Nox4. Silencing Nox2 or Nox4 alone in the SFO significantly attenuates the central AngII-induced pressor response, while silencing both Nox2 and Nox4 together abolishes this response [28]. In contrast, silencing Nox2, but not Nox4 significantly attenuates the central AngII-induced dipsogenic response [28]. Although the reason for the differential role of Nox2 versus Nox4 in mediating central AngII-induced physiological responses remains unclear, one possible explanation may be the different subcellular locations of these Nox homologs. Nox2 is traditionally thought to reside in the plasma membrane, although in central neurons this has not been conclusively demonstrated, while recent studies using peripheral cell types report Nox4 is be localized to mitochondria [29;30]. In a central catecholaminergic neuronal cell line (CATH.a neurons), Nox4 also appears to be mitochondrial localized, as we recently reported (Zimmerman M.C., Hypertension 2010, 56:e58, abstract 27, American Heart Association High Blood Pressure Research 2010 Scientific Session, Washington DC, October 2010). Considering overexpression of the mitochondrial-targeted MnSOD virtually abolishes the AngII-induced increase in intra-neuronal O2•− as measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (Figure 1) and in the brain MnSOD overexpression inhibits the central AngII-induced physiological responses to a similar extent as the primarily cytoplasmic localized CuZnSOD [11], it seems likely that mitochondria are also an important source of O2•− in AngII stimulated neurons. In fact, Yin et al, recently reported that AngII increases mitochondrial O2•− levels in CATH.a neurons and that this increase in mitochondrial O2•− mediates the AngII-induced activation of a redox-sensitive kinase, calcium/calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII), and the AngII-induced inhibition of neuronal potassium current (Ik) [10]. These studies and others [7;8;31] clearly demonstrate the both NADPH oxidase and mitochondria are important sources of O2•− in AngII-stimulated neurons. Additional studies are needed to determine the potentially important link between these two sources of O2•− in mediating the (patho)physiological responses of AngII in the CNS.

Figure 1.

Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of the mitochondrial-localized MnSOD (AdMnSOD) in cultured neurons inhibits the AngII-induced increase in O2•− levels, as measured by EPR spectroscopy. Non-infected (control) or AdMnSOD-infected catecholaminergic neurons (CATH.a neurons) were loaded with the O2•− sensitive, cell permeable spin probe 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine (CMH) and stimulated with AngII (100 nM). AngII significantly increased the EPR amplitude in control neurons (red line) as compared to non-treated neurons (black line), indicating an increase in O2•− levels. This increase in O2•− was virtually abolished in neurons overexpressing MnSOD (blue line), suggesting mitochondria are a primary source of O2•− in AngII-stimulated neurons. A.U. = arbitrary units.

Although it is generally well-accepted that AngII intra-neuronal signaling is mediated, at least in part, by ROS, the downstream redox-sensitive effector mechanisms are yet to be fully elucidated. Few studies both in vivo and in vitro have demonstrated that the AngII-induced increase in O2•− modulates intracellular Ca2+ signaling by inducing the influx of extracellular Ca2+ [8;13]. Additional evidence obtained from neurons in culture indicate that AngII-induced increase in O2•− controls activity of K+ channels [7;10]. By regulating these ion channels and controlling membrane potential, O2•− is believed to play a critical role in increasing the neuronal firing rate of AngII-stimulated neurons. In fact, Raizada and colleagues using NADPH oxidase inhibitors and O2•− scavengers have shown this to be the case [7]. However, it remains unclear if O2•− acts directly on an ion channel protein to control ion flux or if it acts on a signaling protein which in turn controls channel activity. Indicating the latter may be true, at least in regards to K+ channel activity, and as mentioned earlier, increased scavenging of mitochondrial O2•− via MnSOD overexpression in cultured neurons significantly attenuates the AngII-induced activation of CaMKII [10]. Interestingly, CaMKII has recently been identified as a redox-sensitive protein [32] and previous studies have shown that CaMKII is required for the AngII-induced inhibition of neuronal Ik [33;34]. Additional studies are needed to identify other AngII modulated redox-sensitive proteins that are either ion channel subunits or upstream signaling proteins that control channel activity. Once identified as redox-sensitive it will be ideal to determine which amino acids, likely cysteine and/or methionine residues, in the protein are being oxidized/reduced to modulate activity.

As described above, most of the in vivo and in vitro studies to date implicating O2•− as a key intra-neuronal signaling intermediate in AngII-stimulated neurons have utilized SOD overexpression or SOD mimetics. Although concluding that O2•− is an important signaling intermediate when SOD overexpression inhibits the AngII-mediated response is a reasonable interpretation, it must be considered that the H2O2 produced by the efficient scavenging of O2•− by SOD may have an inhibitory effect on AngII signaling. In fact, H2O2 is considered by many to be more of a signaling molecule as compared to O2•− because it is more diffusible and it has been demonstrated to oxidize cysteine and methionine residues [3;32], which in turn can be reduced by appropriate reductases. Few studies have addressed the hypothesis that AngII increases H2O2 levels in cells overexpressing SOD; however, a recent study showed that CuZnSOD inhibition decreases H2O2 levels and attenuates growth factor-induced oxidation of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP) [35]; thus, suggesting that CuZnSOD-produced H2O2 does act as a signaling molecule to modulate activity of downstream effectors. In contrast, in a myocardial infarct-induced heart failure model the improved cardiac performance observed in mice overexpressing CuZnSOD in the PVN was not affected when both CuZnSOD and the H2O2 scavenging enzyme catalase were overexpressed together [22]. This study suggests that CuZnSOD-produced H2O2, at least in the PVN, is not involved in inhibiting the intra-neuronal signaling mechanism(s) that drives the deleterious sympathoexcitation in this model of heart failure. However, it should be noted that although catalase does efficiently scavenge H2O2, it is primarily localized to peroxisomes and thus it is possible that catalase overexpression may not scavenge H2O2 produced in other subcellular compartments. As such, additional studies using other H2O2 scavenging enzymes, like glutathione peroxidases and peroxiredoxins, that are present in other subcellular locations are needed to distinguish the importance, or lack thereof, of H2O2 in central AngII-mediated cardiovascular responses.

Nitric oxide and Ang-(1-7) intra-neuronal signaling

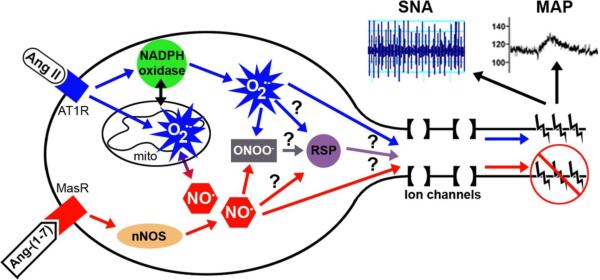

In contrast to the hypertensive actions of AngII via activation of the AT1 receptor, including vasoconstriction and sympathoexcitation, Ang-(1-7) acts through the MasR to induce vasodilation and sympathoinhibition [15;17;36]. In the vasculature, the Ang-(1-7) vasodilatory action is believed to be dependent on an increase in NO• [37;38]. In the brain, it has also be shown that Ang-(1-7) increases NO• levels [39]. In addition, overexpression of ACE2, which cleaves AngII to Ang-(1-7), in the brain prevents the development of hypertension induced by peripheral AngII infusion by, at least in part, increasing nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and NO• [15]. In cultured neurons, Ang-(1-7) increases NO• levels, which mediates activation of K+ current [40]. Ang-(1-7)-induced increase in neuronal K+ current is directly opposite to the inhibition of K+ current induced by AngII (discussed above); thus, suggesting that O2•−-dependent signaling induced by AngII directly opposes that of NO•-dependent signaling induced by Ang-(1-7) (Figure 2). Interestingly, in SHRs the central AngII-induced pressor response is attenuated when Ang-(1-7) and AngII are administered simultaneously [41]. Although the downstream effectors of O2•− and NO• modulated by AngII and Ang-(1-7), respectively, may work to counteract each other, it is tempting to speculate that O2•− and NO• counter-balance each other directly, especially considering the reaction of these two radicals is diffusion limited. However, if this reaction is indeed the mechanism by which AngII and Ang-(1-7) counteract each other, the effects of the reaction product, peroxynitrite (ONOO−), must be investigated. To date, we are unaware of any studies linking AngII and Ang-(1-7) signaling in neurons to changes in ONOO− and/or the downstream signaling targets, if any, of ONOO−.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of AngII and Ang-(1-7) intra-neuronal signaling involving an increase in O2•− and NO•, respectively. AngII, acting through the AT1 receptor (AT1R), has been shown to increase O2•− from both NADPH oxidase and mitochondria (mito), while Ang-(1-7) signaling through the MasR leads to nNOS activation and an increase in NO•. NO• and O2•− react in a diffusion-limited manner to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO−). Previous studies indicate that the AngII-induced increase in O2•− modulates ion channels to increase neuronal firing rate leading to an increase in sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) and mean arterial pressure (MAP). While other studies suggest that the Ang-(1-7)-induced increase in NO• leads to sympatho-inhibition. Future studies (indicated by ?) are needed to determine if O2•−, NO•, and/or ONOO− act on redox-sensitive proteins (RSP) that control ion channel activity or if these reactive species act directly on ion channel proteins to regulate ion flux and neuronal activity.

Antioxidant therapeutic strategies for angiotensin-related neuro-cardiovascular diseases

Most of the clinical trials designed to test the therapeutic efficacy of antioxidant vitamins, such as Vitamin C and E, in cardiovascular diseases have failed [42–46]. Although the reasons for these failed trials are not completely understood, there are a few hypotheses that seem reasonable: 1) The antioxidant vitamins may not target the tissue, cells, or subcellular compartments where the ROS are being primarily generated; 2) The antioxidant vitamins may not scavenge the specific ROS driving the pathophysiological condition; 3) The antioxidant vitamins may not efficiently scavenge the ROS driving the pathophysiological condition and thus some of the ROS are still available to carry out their detrimental signaling. To overcome these potential pitfalls of antioxidant vitamin therapy, numerous groups have developed small molecule antioxidants that have SOD-like and/or catalase-like activity and in most cases these new redox-based therapies have been beneficial in various cardiovascular disease animal models [47–49]. In addition, recent advances in nanotechnology have lead to the development of new cell permeable delivery systems for endogenous antioxidant proteins, including SOD and catalase [50–52]. For example, we recently reported that CuZnSOD protein electrostatically wrapped with a synthetic poly(ethyleneimine)-poly(ethyleneglycol) (PEI-PEG) polymer is taken up by central neurons and inhibits AngII signaling in vitro and in vivo [53]. It is tempting to speculate that these new small molecule and nanomedicine-based antioxidants will be therapeutically efficacious because they posses specific ROS scavenging activities and may be designed to target specific tissues, cells, and even subcellular compartments.

Conclusions

A large collection of literature over the past decade has clearly identified O2•− as an important AngII intra-neuronal signaling intermediate which leads to an increase in neuronal activity and elevated sympathetic output. More recent studies suggest NO• is a key signaling molecule in Ang-(1-7) stimulated neurons which may counteract the signaling events of AngII and O2•− (Figure 2). Future studies are needed to fully elucidate the cross-talk between AngII-O2•− and Ang-(1-7)-NO• intra-neuronal signaling and the downstream redox-sensitive proteins (RSP) involved in controlling neuronal firing rate, sympathetic outflow, and the pathogenesis of neuro-cardiovascular diseases, like hypertension and heart failure. Perhaps more importantly, future studies are needed to identify new redox-based therapeutics that not only works in animal models, but also in patients suffering from these prevalent diseases.

Acknowledgements

M.C.Z. is supported by NIH grants (R01HL103942 and P20RR021937) and an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (0930204N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Clempus RE, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc.Res. 2006;71:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 ••.D'Autreaux B, Toledano MB. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2007;8:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A comprehensive review of ROS signaling through chemical reactions focused on ROS pathway specificity and mechanism that control the specificity.

- 3.Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol.Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sumners C, Fleegal MA, Zhu M. Angiotensin AT1 receptor signalling pathways in neurons. Clin.Exp.Pharmacol.Physiol. 2002;29:483–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson SH, Wyss JM. Neurohormonal regulation of the sympathetic nervous system: new insights into central mechanisms of action. Curr.Hypertens.Rep. 2008;10:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zucker IH. Novel mechanisms of sympathetic regulation in chronic heart failure. Hypertension. 2006;48:1005–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000246614.47231.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 ••.Sun C, Sellers KW, Sumners C, Raizada MK. NAD(P)H oxidase inhibition attenuates neuronal chronotropic actions of angiotensin II. Circ.Res. 2005;96:659–666. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000161257.02571.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study clearly demonstrated that the AngII-induced inhibition of neuronal K+ current and increase in neuronal firing rate is mediated by superoxide generated by NADPH oxidase.

- 8.Wang G, Anrather J, Huang J, Speth RC, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. NADPH oxidase contributes to angiotensin II signaling in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J.Neurosci. 2004;24:5516–5524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1176-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G, Anrather J, Glass MJ, Tarsitano MJ, Zhou P, Frys KA, Pickel VM, Iadecola C. Nox2, Ca2+, and protein kinase C play a role in angiotensin II-induced free radical production in nucleus tractus solitarius. Hypertension. 2006;48:482–489. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000236647.55200.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 •.Yin JX, Yang RF, Li S, Renshaw AO, Li YL, Schultz HD, Zimmerman MC. Mitochondria-produced superoxide mediates angiotensin II-induced inhibition of neuronal potassium current. Am.J.Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C857–C865. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00313.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study clearly demonstrated that AngII increases superoxide levels in neuron mitochondria and that scavenging mitochondrial superoxide inhibits AngII-induced electrophysiological responses in cultured neurons.

- 11 ••.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Lang JA, Sinnayah P, Ahmad IM, Spitz DR, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates the actions of angiotensin II in the central nervous system. Circ.Res. 2002;91:1038–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043501.47934.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first study demonstrating that both CuZnSOD and MnSOD overexpression in the brain via adenovirus-mediated gene transfer attenuates the pressor and dipsogenic response of central AngII; thus, indicating superoxide is a key signaling intermediate in central AngII-induced cardiovascular responses.

- 12.Zimmerman MC, Lazartigues E, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Hypertension caused by angiotensin II infusion involves increased superoxide production in the central nervous system. Circ.Res. 2004;95:210–216. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000135483.12297.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman MC, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Superoxide mediates angiotensin II-induced influx of extracellular calcium in neural cells. Hypertension. 2005;45:717–723. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153463.22621.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ. Angiotensin-(1-7) and the renin-angiotensin system. Curr.Opin.Nephrol.Hypertens. 2007;16:122–128. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328031f362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15 ••.Feng Y, Xia H, Cai Y, Halabi CM, Becker LK, Santos RA, Speth RC, Sigmund CD, Lazartigues E. Brain-selective overexpression of human Angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 attenuates neurogenic hypertension. Circ.Res. 2010;106:373–382. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study showed that increased levels of Ang-(1-7) in the brain via ACE2 overexpression increases nitric oxide.

- 16 •.Gironacci MM, Vatta M, Rodriguez-Fermepin M, Fernandez BE, Pena C. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces norepinephrine release through a nitric oxide mechanism in rat hypothalamus. Hypertension. 2000;35:1248–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.6.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study demonstrated that a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism mediated that inhibitory action of Ang-(1-7) in the central nervous system.

- 17.Patel KP. Role of paraventricular nucleus in mediating sympathetic outflow in heart failure. Heart Fail.Rev. 2000;5:73–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1009850224802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18 ••.Zanzinger J, Czachurski J. Chronic oxidative stress in the RVLM modulates sympathetic control of circulation in pigs. Pflugers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. 2000;439:489–494. doi: 10.1007/s004249900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first study to show that SOD injected into the RVLM inhibits baseline sympathetic nerve activity.

- 19.Okado-Matsumoto A, Fridovich I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu,Zn-SOD in mitochondria. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:38388–38393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan SH, Tai MH, Li CY, Chan JY. Reduction in molecular synthesis or enzyme activity of superoxide dismutases and catalase contributes to oxidative stress and neurogenic hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2006;40:2028–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao L, Wang W, Li YL, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, Zucker IH. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ.Res. 2004;95:937–944. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146676.04359.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Infanger DW, Cao X, Butler SD, Burmeister MA, Zhou Y, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Silencing nox4 in the paraventricular nucleus improves myocardial infarction-induced cardiac dysfunction by attenuating sympathoexcitation and periinfarct apoptosis. Circ.Res. 2010;106:1763–1774. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23 •.Lindley TE, Doobay MF, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Superoxide is involved in the central nervous system activation and sympathoexcitation of myocardial infarction-induced heart failure. Circ.Res. 2004;94:402–409. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000112964.40701.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study clearly demonstrated that increase scavenging of superoxide in the brain via CuZnSOD overexpression decreases sympathetic drive in a myocardial infarction-induced heart failure.

- 24.Lindley TE, Infanger DW, Rishniw M, Zhou Y, Doobay MF, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Scavenging superoxide selectively in mouse forebrain is associated with improved cardiac function and survival following myocardial infarction. Am.J.Physiol Regul.Integr.Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1–R8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00078.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25 •.Lob HE, Marvar PJ, Guzik TJ, Sharma S, McCann LA, Weyand C, Gordon FJ, Harrison DG. Induction of hypertension and peripheral inflammation by reduction of extracellular superoxide dismutase in the central nervous system. Hypertension. 2010;55:277–83. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study to show that extracellular superoxide in the brain plays a role in the regulation of systemic blood pressure by, at least in part, controlling sympathetic output.

- 26.Chan SH, Hsu KS, Huang CC, Wang LL, Ou CC, Chan JY. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced pressor effect via activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Circ.Res. 2005;97:772–780. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185804.79157.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmerman MC, Dunlay RP, Lazartigues E, Zhang Y, Sharma RV, Engelhardt JF, Davisson RL. Requirement for Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase in the cardiovascular and dipsogenic actions of angiotensin II in the brain. Circ.Res. 2004;95:532–539. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000139957.22530.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson JR, Burmeister MA, Tian X, Zhou Y, Guruju MR, Stupinski JA, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. Genetic silencing of Nox2 and Nox4 reveals differential roles of these NADPH oxidase homologues in the vasopressor and dipsogenic effects of brain angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2009;54:1106–1114. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ago T, Kuroda J, Pain J, Fu C, Li H, Sadoshima J. Upregulation of Nox4 by hypertrophic stimuli promotes apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac myocytes. Circ.Res. 2010;106:1253–1264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30 ••.Block K, Gorin Y, Abboud HE. Subcellular localization of Nox4 and regulation in diabetes. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2009;106:14385–14390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906805106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The first study to show that Nox4, one of the NADPH oxidase catalytic subunit homologs, is localized to mitochondria; thus, suggesting a direct link between NADPH oxidase- and mitochondrial-derived ROS.

- 31.Nozoe M, Hirooka Y, Koga Y, Araki S, Konno S, Kishi T, Ide T, Sunagawa K. Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species mediate sympathoexcitation induced by angiotensin II in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. J.Hypertens. 2008;26:2176–2184. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830dd5d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O'Donnell SE, ykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun C, Sumners C, Raizada MK. Chronotropic action of angiotensin II in neurons via protein kinase C and CaMKII. Hypertension. 2002;39:562–566. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun C, Du J, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Modulation of delayed rectifier potassium current by angiotensin II in CATH.a cells. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2003;310:710–714. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juarez JC, Manuia M, Burnett ME, Betancourt O, Boivin B, Shaw DE, Tonks NK, Mazar AP, Donate F. Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is essential for H2O2-mediated oxidation and inactivation of phosphatases in growth factor signaling. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008;105:7147–7152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709451105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Pinheiro SV, Sampaio WO, Touyz R, Santos MJ. Angiotensin-(1-7) and its receptor as a potential targets for new cardiovascular drugs. Expert.Opin.Investig.Drugs. 2005;14:1019–1031. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brosnihan KB, Li P, Tallant EA, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-(1-7): a novel vasodilator of the coronary circulation. Biol.Res. 1998;31:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38 ••.Ferrario CM, Ahmad S, Joyner J, Varagic J. Advances in the renin angiotensin system focus on angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-(1-7) Adv.Pharmacol. 2010;59:197–233. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(10)59007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The actions of ACE2 and Ang-(1-7), and the opposing actions of Ang-(1-7) as compared to AngII are discussed in this review.

- 39.Zhang Y, Lu J, Shi J, Lin X, Dong J, Zhang S, Liu Y, Tong Q. Central administration of angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates nitric oxide release and upregulates the endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Neuropeptides. 2008;42:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang RF, Yin JX, Li YL, Zimmerman MC, Schultz HD. Angiotensin-(1-7) Increases Neuronal Potassium Current via a Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanism. Am.J.Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hocht C, Opezzo JA, Gironacci MM, Pena C, Taira CA. Hypothalamic cardiovascular effects of angiotensin-(1-7) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Regul.Pept. 2006;135:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song Y, Cook NR, Albert CM, Van DM, Manson JE. Effects of vitamins C and E and beta-carotene on the risk of type 2 diabetes in women at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a randomized controlled trial. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2009;90:429–437. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43 ••.Bruckdorfer KR. Antioxidants and CVD. Proc.Nutr.Soc. 2008;67:214–222. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108007052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is a comprehensive review summarizing the results of clinical trials using antioxidant vitamins. Discussion as to why most of these trials have failed is included.

- 44.Lonn E, Bosch J, Yusuf S, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Arnold JM, Ross C, Arnold A, Sleight P, Probstfield J, Dagenais GR. Effects of long-term vitamin E supplementation on cardiovascular events and cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1338–1347. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoogwerf BJ, Young JB. The HOPE study. Ramipril lowered cardiovascular risk, but vitamin E did not. Cleve.Clin.J.Med. 2000;67:287–293. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.67.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCance DR, Holmes VA, Maresh MJ, Patterson CC, Walker JD, Pearson DW, Young IS. Vitamins C and E for prevention of pre-eclampsia in women with type 1 diabetes (DAPIT): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:259–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60630-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47 •.Day BJ. Catalytic antioxidants: a radical approach to new therapeutics. Drug Discov.Today. 2004;9:557–566. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This comprehensive review discusses the newly developed catalytic antioxidants that have been shown to have beneficial effects in numerous cardiovascular disease model systems.

- 48.Batinic-Haberle I, Reboucas JS, Spasojevic I. Superoxide dismutase mimics: chemistry, pharmacology, and therapeutic potential. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2010;13:877–918. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simonsen U, Christensen FH, Buus NH. The effect of tempol on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and blood pressure. Pharmacol.Ther. 2009;122:109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddy MK, Labhasetwar V. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of superoxide dismutase to the brain: an effective strategy to reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2009;23:1384–1395. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-116947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Y, Haney MJ, Klyachko NL, Li S, Booth SL, Higginbotham SM, Jones J, Zimmerman MC, Mosley RL, Kabanov AV, Gendelman HE, Batrakova EV. Polyelectrolyte complex optimization for macrophage delivery of redox enzyme nanoparticles. Nanomedicine.(Lond) 2011;6:25–42. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yi X, Zimmerman MC, Yang R, Tong J, Vinogradov S, Kabanov AV. Pluronic-modified superoxide dismutase 1 attenuates angiotensin II-induced increase in intracellular superoxide in neurons. Free Radic.Biol.Med. 2010;49:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53 •.Rosenbaugh EG, Roat JW, Gao L, Yang RF, Manickam DS, Yin JX, Schultz HD, Bronich TK, Batrakova EV, Kabanov AV, Zucker IH, Zimmerman MC. The attenuation of central angiotensin II-dependent pressor response and intraneuronal signaling by intracarotid injection of nanoformulated copper/zinc superoxide dismutase. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5218–5226. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first study to demonstrate that nanoformulated CuZnSOD is taken up by neurons and inhibits AngII intra-neuronal signaling both in vitro and in vivo.