Abstract

Objective

To determine if valproic acid (VPA)-associated ALF (VPA-ALF) explains the poor outcomes following liver transplantation (LT) in children.

Study design

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data of pediatric patients who underwent LT for VPA-ALF and ALF secondary to other drugs (nonVPA- drug-induced acute liver failure [DIALF]) were analyzed. Pre- and post-transplant variables and post-LT survival were compared between VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF.

Results

Seventeen children were transplanted for VPA-ALF. Of those, 82% died within one year of LT. Pre- and post-transplant parameters of VPA versus nonVPA-DIALF were comparable with two exceptions. Median alanine aminotransferase at transplant was remarkably lower in VPA-ALF compared with nonVPA-DIALF (45 versus 1179 IU/L, P=0.004). One-year survival probability was worse in VPA-ALF than nonVPA-DIALF (20% versus 69%, P<0.0001). Median post-LT survival time for VPA-ALF was 2.8 months.

Conclusion

Children who underwent LT for VPA-ALF had significantly lower survival probability than those with nonVPA-DIALF. Current data suggest that VPA-ALF in children represents an “unmasking” of mitochondrial disease. VPA-ALF should be a contraindication for LT, even in the absence of a documented mitochondrial disease.

Keywords: Children, valproic acid, mitochondria, seizure, hepatotoxicity, POLG1

Drug-induced acute liver failure (DIALF) is a well-known complication of valproic acid (VPA) treatment; this occurs primarily in children younger than 2 years (1–4). Mechanisms involved in VPA-associated hepatotoxicity and ALF include generation of toxic VPA metabolites (e.g. 2-n-propyl-4-pentanoic acid), inhibition of mitochondrial β-oxidation, depletion of hepatic free CoA reserves, carnitine deficiency and inborn mitochondrial disorders (5–10).

Liver transplantation (LT) is an ultimate treatment for DIALF with one-year patient survival probabilities of 76% for ALF associated with acetaminophen and 82% for ALF associated with antituberculosis agents and antibiotics (4). However, a lower post-LT survival was observed in children who developed DIALF due to antiepileptics, particularly VPA-associated ALF (VPA-ALF) (4, 11, 12). Regardless of LT and good hepatic graft function, children who developed VPA-ALF had continuing neurological deterioration after LT (11, 12). Although the cause is unclear, inborn mitochondrial dysfunction is postulated as a major risk factor for VPA-ALF (6, 12–14) and poor survival after LT (12). Moreover, Delarue et al (11) suggested that children with Alpers-Hutterlocher syndrome (15, 16), an inborn mitochondrial defect, who developed ALF on VPA therapy were often misdiagnosed as VPA-ALF and eventually had a poor outcome after LT. Indeed, children who develop ALF not related to VPA, but secondary to a mitochondrial defect, were shown to have reduced survival after LT (17–21). Thomson et al (18) suggested that ALF induced by a mitochondrial cytopathy be a contraindication for LT.

Herein, we report a child heterozygous for POLG1 mutations who developed VPA-ALF and improved without LT. We have previously shown that being younger than 18 years and undergoing LT for antiepileptic-induced ALF were independent risk factors for post-LT mortality (4). Therefore, in addition to the case presentation, we analyzed data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) to determine if children transplanted for VPA-ALF had lower survival probability after LT compared with children transplanted for ALF secondary to other drugs (nonVPA-DIALF).

Methods

Case presentation

An 18-month-old boy with a history of a seizure disorder developed ALF in the setting of valproic acid (VPA) therapy. He was healthy for his first year of life with the exception of a delay in motor and language milestones. At one year, he presented with generalized seizures and was treated with phenobarbital. Three months prior to presentation, VPA and oxcarbazepine were added for refractory seizures. Somnolence that occurred one month prior to his presentation was attributed to high VPA levels. One week prior to referral, he was admitted for persistently elevated VPA levels, liver dysfunction and pancytopenia. At that time, he had an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 240 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 91 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase level of 3084 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level of 212 IU/L, total bilirubin level of 4.8 mg/dL, direct bilirubin level of 2.0 mg/dL, ammonia level of 91 µmol/L, prothrombin time (PT) of 21.2 seconds, white blood cell count of 4.2 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 10 g/dl and platelet count of 29 × 109/L. Phenobarbital and VPA were discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests revealed an international normalized ratio (INR) of 10.7, total bilirubin level of 9.3 mg/dL, AST level of 56 IU/L and ALT level of 32 IU/L. Because of clinical concern for ALF, he was transferred for evaluation for LT. Upon arrival, he was sleepy but interactive. Oral carnitine therapy was initiated. Further evaluation included normal ferritin, triglyceride, creatine phosphokinase levels and acyl carnitine profile. A mitochondrial disorder was suspected. A skeletal muscle biopsy was unremarkable. Liver biopsy revealed many hepatocytes with expanded eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (oncocytic change), early bridging fibrosis, widespread and spectacular bile ductular proliferation and neocholangiolization of hepatocytes. Electron microscopy demonstrated hepatocytes with markedly increased numbers of mitochondria essentially filling the cytoplasm and pushing the nucleus to the periphery of the cell. The mitochondria varied in shape and size with increased flocculent granular matrix obscuring the normal pattern of cristae. Dense matrical granules normally present were sparse. Two distinct heterozygous missense mutations in DNA POLG1 were detected (E1143G and G888D). Electron transport chain analysis showed partial deficiencies in the mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes I and IV with the patient having 23–30% of complex I and 13–17% of complex IV (both compared with respective controls corrected for low citrate synthase activity). These findings confirmed the presence of a mitochondrial disorder. In light of the POLG-based mitochondrial disorder and in consideration of the generally poor prognosis of LT following VPA-ALF, he was declined as a candidate for transplant. The patient's family endorsed this recommendation. Somewhat surprisingly, his liver and bone marrow disease resolved after discontinuation of VPA and initiation of carnitine therapy. One year after presentation, he has no clinical evidence of significant liver disease.

Analysis of OPTN data

The analysis was based on OPTN data as of August 25, 2009. Standard Transplant Analysis and Research (STAR) dataset files that contain pre- and post transplant data of pediatric patients who were transplanted between October 01, 1987 and June 25, 2008 were analyzed. The focus of this investigation was VPA-ALF. Because the majority of children with VPA-ALF were younger than 8 years of age, subsequent analyses excluded children who were older than 7 years and transplanted for a diagnosis other than DIALF. The pre- and post-transplant variables included in the analysis were recipient status at transplant, diagnosis, age, sex, race or ethnicity, recipient life support at registration and transplant, grade III or grade IV encephalopathy at transplant, dialysis in the week prior to transplant, days from transplant to death or last follow-up, post-transplant status at last follow-up, serum total bilirubin, serum creatinine, serum albumin, serum ALT, INR, cold and warm ischemia time, days on the LT waiting list, ABO blood type, donor type (cadaveric or living) and type of liver (split or whole).

The analysis was performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA) (22). The survival plot was drawn using Minitab® Statistical Software (Minitab Inc, State College, PA) (23). Chi-square and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests were used to assess differences between children who underwent LT due to VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF for categorical and not normally distributed quantitative variables, respectively. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Survival time was defined as the time from first transplant to death. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the survival function. Log-rank test was used to compare survival functions between children who underwent LT for VPA-ALF and other drugs.

RESULTS

There were a total of 98 patients younger than 18 years who underwent LT for DIALF in the U.S. since 1987 and 17 were transplanted for VPA-ALF (Table I). Fifteen of 17 children with VPA-ALF were less than 8 years of age. Therefore, comparative analyses were focused on children less than 8 years of age. Similar results were obtained when the entire cohort was analyzed. Forty-two of 98 children were less than 8 years; of these, 15 (36%) underwent LT for VPA-ALF and 27 (64%) for nonVPA-DIALF.

Table 1.

Recipient and Donor Characteristics of 17 Children Transplanted for VPA-ALF in the US

| Recipient Characteristics | Donor Characteristics | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age | Sex | Serum Total Bilirubin at Transplant (mg/dL) | Serum Creatinine at Transplant (mg/dL) | ALT at Transplant (IU/mL) | Life Support at Transplant | Grade III or IV encephalopathy at transplant | Status 1, 1A, 1B | Days on the Liver Waiting List | Post-LT Survival Status at last follow-up | Months until Death | Number of LT | Cold Ischemia Time (hour) | Warm Ischemia Time (minute) | Donor Type | Type of Liver |

| 1 | 7 | Male | 33.0 | 0.9 | 27 | Yes | U | Yes | 14 | Death | 8 | 1 | 15 | 81 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 2 | 3 | Female | 28.2 | 0.2 | 40 | Yes | U | No | 8 | Death | 3 | 2 | 10 | 51 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 3 | 1 | Female | 24.7 | 0.2 | 44 | Yes | U | No | 5 | Death | 1 | 1 | 7 | 35 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 4 | 1 | Male | 21.7 | 0.1 | 46 | Yes | U | No | 5 | Death | 1 | 1 | 12 | 89 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 5 | 13 | Female | 32.7 | 0.4 | U | Yes | Yes | Yes | 30 | Death | 6 | 1 | 13.7 | 60 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 6 | 2 | Female | 8.2 | 0.6 | 101 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | Death | 4 | 1 | U | U | Living | Split |

| 7 | 6 | Male | 30.3 | 0.5 | U | Yes | No | Yes | 6 | Death | 2 | 2 | 16 | 25 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 8 | 2 | Male | U | 0.2 | U | No | No | Yes | 3 | Death | 15 | 1 | 6 | 26 | Cadaveric | Split |

| 9 | 4 | Male | 1.0 | 3.9 | U | Yes | U | Yes | 1 | Death | 1 | 2 | 8 | U | Cadaveric | Split |

| 10 | 1 | Male | 9.9 | 0.4 | U | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | Death | 73 | 1 | 6.4 | 46 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 11 | 16 | Female | 6.1 | 0.9 | 27 | No | U | No | 84 | Death | 1 | 1 | 5 | 70 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 12 | 4 | Female | 21.1 | 0.2 | 71 | No | U | Yes | 8 | Death | 2 | 1 | 10 | 55 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 13 | 3 | Male | 31.1 | 0.3 | 35 | No | U | No | 20 | Death | 3 | 2 | 10 | 148 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 14 | 1 | Female | 3.6 | 0.3 | 1520 | Yes | U | Yes | 0 | Death | 4 | 1 | U | 35 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 15 | 6 | Female | 23.4 | 1.1 | 61 | No | U | Yes | 10 | Death | 9 | 1 | 14 | 47 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 16 | 4 | Female | 18.8 | 0.5 | 26 | Yes | U | Yes | 3 | Death | 2 | 1 | 7.58 | 85 | Cadaveric | Whole |

| 17 | 3 | Female | 10.0 | 0.3 | U | No | Yes | No | 8 | Death | 117 | 1 | 6 | U | Cadaveric | Split |

U: Unknown

Table II shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of 42 children less than 8 years and transplanted for DIALF. Although median serum total bilirubin level was similar in both groups, median ALT levels were remarkably lower in the VPA-ALF compared with nonVPA-DIALF group (ALT=45, interquartile range [IQR]=36 versus ALT=1179, IQR=2243 IU/L, P=0.004) (Table II). INR at the time of transplant was reported only in one child (patient # 9 in Table I) in the VPA-ALF group (INR=1.9) and in 6 children who underwent LT for nonVPA-DIALF (median INR=2.3, IQR=1.3).

Table 2.

Recipient and Donor Characteristics of 42 Children who were less than 8 Years of Age and Transplanted for VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF1,2

| VPA-ALF N=15 | nonVPA-DIALF N=27 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 (36) | 27 (64) | |||

| Sex-no. (%) | 0.581 | |||

| Female | 8 (53) | 12 (44) | ||

| Male | 7 (47) | 15 (56) | ||

| Race or Ethnicity-no. (%) | 0.139 | |||

| White | 12 (80) | 15 (56) | ||

| Black | 3 (20) | 4 (15) | ||

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 7 (26) | ||

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | ||

| ABO Blood Type-no. (%) | 0.167 | |||

| A | 9 (60) | 11 (41) | ||

| B | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | ||

| AB | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | ||

| O | 5 (33) | 12 (44) | ||

| Dialysis Prior Week to Transplant-no. (%) | 0.493 | |||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | ||

| No | 6 (40) | 12 (44) | ||

| Unknown | 9 (60) | 13 (48) | ||

| Post LT Survival Status at Last Follow-up-no. (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Alive | 0 (0) | 18 (67) | ||

| Death | 15 (100) | 9 (33) | ||

| Life Support at Registration-no. (%) | 0.115 | |||

| Yes | 9 (60) | 9 (35) | ||

| No | 6 (40) | 17 (65) | ||

| Life Support at Transplant-no. (%) | 0.107 | |||

| Yes | 10 (67) | 11 (41) | ||

| No | 5 (33) | 16 (59) | ||

| Grade III or IV Encephalopathy at Transplant-no. (%) | 0.871 | |||

| Yes | 3 (20) | 6 (27) | ||

| No | 2 (13) | 3 (14) | ||

| Unknown | 10 (67) | 13 (59) | ||

| Number of Transplants-no. (%) | 0.047 | |||

| 1 | 11.0 (73) | 23.0 (85) | ||

| 2 | 4.0 (27) | 1.0 (4) | ||

| 3 | 0.0 (0) | 3.0 (11) | ||

| Status 1, 1A, 1B-no. (%) | 0.433 | |||

| Yes | 10 (67) | 21 (78) | ||

| No | 5 (33) | 6 (22) | ||

| Donor Type-no. (%) | 0.929 | |||

| Cadaveric | 14 (93) | 25 (93) | ||

| Living | 1 (7) | 2 (7) | ||

| Type of Transplanted Liver-no. (%) | 0.195 | |||

| Split | 4 (27) | 3.0 (11) | ||

| Whole | 11 (73) | 24.0 (89) | ||

| Age (yr) | 3.0 (3) | 4.0 (3) | 0.097 | |

| Serum Total Bilirubin at Transplant (mg/dL) | 21.4 (18) | 16.2 (14) | 0.356 | |

| Serum Albumin at Transplant (mg/dL) | 3.3 (1) | 2.9 (1) | 0.975 | |

| Serum Creatinine at Transplant (mg/dL) | 0.3 (0) | 0.5 (0) | 0.318 | |

| ALT at Transplant (IU/mL) | 45.0 (36) | 1179.0 (2243) | 0.004 | |

| Days on the Liver Waiting List | 5.0 (6) | 4.0 (10) | 0.746 | |

| Cold Ischemia Time (hr) | 10.0 (5) | 7.5 (4) | 0.117 | |

| Warm Ischemia Time (min) | 49.0 (48) | 48.0 (45) | 0.825 |

Acetaminophen, isoniazid, propylthiouracil, gancyclovir and cefprozil, iron, phenytoin, carbamazepine, pemoline, a chemotherapy drug, dactinomycin, halothane, isoflorane, risperdal and two unknown drugs.

Chi-square and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests were used to assess differences between children who underwent LT due to VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF for categorical and not normally distributed quantitative variables, respectively. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Quantitative variables were reported as median (interquartile range).

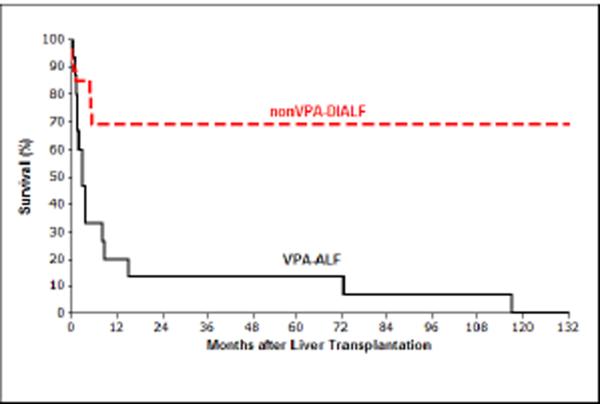

Children with VPA-ALF who underwent LT had significantly worse survival compared with children transplanted for nonVPA-DIALF (P<0.0001) (Figure). There were no long-term survivors in children who underwent LT for VPA-ALF (Table I). One-year survival probabilities for children who underwent LT for VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF were 20% and 69%, respectively (Figure). The median survival time after LT for children who had VPA-ALF was 2.8 months. The median survival time for the nonVPA-DIALF group could not be calculated; but 69% survived the first 5 months, and only one additional child in this group died, 17 years after transplantation. Fourteen of 17 children who were transplanted for VPA-ALF died in the first year after LT (Table I).

Figure.

Among children who were 7 years or younger, those with VPA-ALF who underwent LT had significantly worse survival compared with children who were transplanted for nonVPA-DIALF (P<0.0001). One-year survival probabilities for children who underwent LT for VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF were 20% and 69%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Drug-induced liver injury is an important cause of ALF in children and frequently necessitates LT (4, 24). Antiepileptic medications constitute a large portion of all causes of DIALF (4). In particular, VPA is associated with severe hepatic complications (25, 26). DIALF secondary to VPA is distinct from other forms of DIALF. In particular, these patients have minimal elevation in serum aminotransaminases, suggesting that hepatocellular necrosis is not a major part of the pathophysiology. Liver dysfunction and perhaps encephalopathy may be more related to the toxicity of intermediate metabolites (10, 27, 28). As such, this may be more reversible than other forms of liver failure, especially if the offending agent is stopped and treatment with carnitine is instituted in a timely fashion (27, 29–31).

Our analysis demonstrates clearly that VPA-ALF results in a significantly worse outcome following LT compared with nonVPA-DIALF. Strikingly, there were no long-term survivors among patients receiving LT following VPA-ALF (maximum survival of 119 months in one patient), and patients with nonVPA-DIALF had a long-term survival approaching 70%, consistent with prior studies (4, 24). Several authors reported a poor outcome following LT for VPA-ALF (4, 11, 12, 32). Some of these were due to progressive neurological deterioration despite adequate hepatic function post-transplant (11, 12). Thomson et al (32) reported 5 children between ages of 15 months and 3 years who underwent LT for VPA-ALF, subsequently had severe neurological deterioration after LT and died in one to eleven months post LT. Authors reported that these children had characteristic features of Huttenlocher variant of Alpers' syndrome (15, 16, 32). Kayihan et al (12) described a 13-year-old girl who developed ALF 5 months after initiation of VPA treatment. Following LT, her neurological status deteriorated rapidly and she died 6 months after transplant with reportedly normal liver function (12). She was suspected to have the Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome, attributed to mutations in POLG1 (12, 13, 15, 16). Delarue et al (11) reported a 3-year-old child who developed ALF due to Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome misdiagnosed as VPA-ALF and died 4 months after LT despite normal liver function. McFarland et al (13) reported two children who developed VPA-ALF and completely recovered after discontinuation of VPA. Authors suggested that VPA-associated hepatotoxicity might be reversible in children with a POLG1 mutation, particularly in those with E1143G substitution (13). Our patient had this favorable mutation. We hypothesize that post-LT poor outcomes in children transplanted for VPA-ALF are most likely related to an underlying systemic disease, such as a mitochondrial disorder, which is not corrected by LT. It is possible that LT and post-LT immunosuppressive therapy may accelerate the extrahepatic manifestations of mitochondrial disease (12).

Children with mitochondrial disorders can present with new onset or suddenly worsening seizures (9). These seizure disorders are often rapidly progressive and require escalating antiepileptic therapy, which may include VPA (9). As mitochondrial disorders are often difficult and time-consuming to diagnose and are a relatively rare cause of seizures in children, they are often not diagnosed prior to initiation of antiepileptic therapy (9). Genetic analyses are used more frequently to diagnose mitochondrial disorders, especially those that are based in the genomic rather than mitochondrial DNA (9, 33). Certain mutations, like POLG1 [POLG mutations were found to be associated with Alpers' syndrome (34–36)] seem to predispose patients to marked toxicity from VPA (13) and are associated with a poor long-term neurologic prognosis, especially in males (37). A recent study in adults revealed a strong association between POLG mutations and VPA hepatotoxicity (38).

Our retrospective study has limitations. We were not able to confirm the presence of a mitochondrial defect in children transplanted for VPA-ALF and who died soon after LT. In addition, data regarding pre-LT encephalopathy, INR and post-LT course as well as the cause of death was either missing or limited. Four patients required early re-transplantation presumably for graft related complications. Post transplant graft function, potential impact of re-transplantation as well as graft related morbidity, infectious or technical complications on patients with early post transplant mortality were not analyzed. We did not perform a multivariate survival analysis controlling for potential post-LT confounders (eg, pretransplant laboratory parameters, cold and warm ischemia times, donor liver, type of transplanted liver) as the number of children who were transplanted for VPA-ALF were limited to only 17. Nonetheless, univariate analysis did not show significant differences in pre- and post-LT variables between the VPA-ALF and nonVPA-DIALF groups except in serum ALT levels (Table II).

In summary, in the setting of a child with a progressive seizure disorder and ALF following VPA therapy, we suggest that VPA therapy be discontinued and carnitine be initiated while an evaluation for a presumed mitochondrial disorder is undertaken (6, 11–13, 17–21, 39, 40). Given the poor outcome of LT following DIALF from VPA, we suggest that VPA-ALF should be a contraindication for LT, even in the absence of a documented mitochondrial disease.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Jean-Pierre Raufman, M.D. (Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Maryland School of Medicine) for his valuable input in our manuscript.

The project described was supported in part by Grant Number 1 K23 DK089008-01 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (to Ayse L. Mindikoglu, M.D., M.P.H.) and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the NIH.

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abstract of this manuscript entitled “Valproic Acid-Induced Acute Liver Failure in Children: Analysis of 20 Years of Liver Transplant Experience in the United States” was presented at the 61st Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases held in Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 29 to Nov 2, 2010 and published in Hepatology 2010; 52 (Suppl): 77A (Abstract # 59).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryant AE, 3rd, Dreifuss FE. Valproic acid hepatic fatalities. III. U.S. experience since 1986. Neurology. 1996;46:465–469. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dreifuss FE, Langer DH. Hepatic considerations in the use of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 1987;28(Suppl 2):S23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb05768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dreifuss FE, Santilli N, Langer DH, Sweeney KP, Moline KA, Menander KB. Valproic acid hepatic fatalities: a retrospective review. Neurology. 1987;37:379–385. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mindikoglu AL, Magder LS, Regev A. Outcome of liver transplantation for drug-induced acute liver failure in the United States: analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:719–729. doi: 10.1002/lt.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fromenty B, Pessayre D. Inhibition of mitochondrial beta-oxidation as a mechanism of hepatotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;67:101–154. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krahenbuhl S, Brandner S, Kleinle S, Liechti S, Straumann D. Mitochondrial diseases represent a risk factor for valproate-induced fulminant liver failure. Liver. 2000;20:346–348. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponchaut S, van Hoof F, Veitch K. In vitro effects of valproate and valproate metabolites on mitochondrial oxidations. Relevance of CoA sequestration to the observed inhibitions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;43:2435–2442. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90324-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponchaut S, Veitch K. Valproate and mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:199–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90404-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debray FG, Lambert M, Mitchell GA. Disorders of mitochondrial function. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:471–482. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328306ebb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva MF, Aires CC, Luis PB, Ruiter JP, Ijlst L, Duran M, Wanders RJ, et al. Valproic acid metabolism and its effects on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation: A review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delarue A, Paut O, Guys JM, Montfort MF, Lethel V, Roquelaure B, Pellissier JF, et al. Inappropriate liver transplantation in a child with Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome misdiagnosed as valproate-induced acute liver failure. Pediatr Transplant. 2000;4:67–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2000.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kayihan N, Nennesmo I, Ericzon BG, Nemeth A. Fatal deterioration of neurological disease after orthotopic liver transplantation for valproic acid-induced liver damage. Pediatr Transplant. 2000;4:211–214. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2000.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McFarland R, Hudson G, Taylor RW, Green SH, Hodges S, McKiernan PJ, Chinnery PF, et al. Reversible valproate hepatotoxicity due to mutations in mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma (POLG1) Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:151–153. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.122911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appleton RE, Farrell K, Applegarth DA, Dimmick JE, Wong LT, Davidson AG. The high incidence of valproate hepatotoxicity in infants may relate to familial metabolic defects. Can J Neurol Sci. 1990;17:145–148. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100030353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpers BJ. Diffuse progressive degeneration of gray matter of cerebrum. Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1931;25:469–505. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huttenlocher PR, Solitare GB, Adams G. Infantile diffuse cerebral degeneration with hepatic cirrhosis. Arch Neurol. 1976;33:186–192. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500030042009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubern B, Broue P, Dubuisson C, Cormier-Daire V, Habes D, Chardot C, Devictor D, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation for mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders: a study of 5 children. Transplantation. 2001;71:633–637. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200103150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson M, McKiernan P, Buckels J, Mayer D, Kelly D. Generalised mitochondrial cytopathy is an absolute contraindication to orthotopic liver transplant in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;26:478–481. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199804000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WS, Sokol RJ. Mitochondrial hepatopathies: advances in genetics and pathogenesis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1555–1565. doi: 10.1002/hep.21710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sokal EM, Sokol R, Cormier V, Lacaille F, McKiernan P, Van Spronsen FJ, Bernard O, et al. Liver transplantation in mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158(Suppl 2):S81–84. doi: 10.1007/pl00014328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabinowitz SS, Gelfond D, Chen CK, Gloster ES, Whitington PF, Sacconi S, Salviati L, et al. Hepatocerebral mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome: clinical and morphologic features of a nuclear gene mutation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAS software . The data analysis for this paper was generated using SAS software, Version 9.2 of the SAS System for Windows. [Google Scholar]; Copyright © 2002–2008 SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

- 23.Minitab 15 Statistical Software . State College PM, Inc.; 2007. Computer software. www.minitab.com. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russo MW, Galanko JA, Shrestha R, Fried MW, Watkins P. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure from drug induced liver injury in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1018–1023. doi: 10.1002/lt.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parra J, Iriarte J, Pierre-Louis SJ. Valproate toxicity. Neurology. 1996;47:1608. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konig SA, Siemes H, Blaker F, Boenigk E, Gross-Selbeck G, Hanefeld F, Haas N, et al. Severe hepatotoxicity during valproate therapy: an update and report of eight new fatalities. Epilepsia. 1994;35:1005–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raskind JY, El-Chaar GM. The role of carnitine supplementation during valproic acid therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:630–638. doi: 10.1345/aph.19242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siemes H, Nau H, Schultze K, Wittfoht W, Drews E, Penzien J, Seidel U. Valproate (VPA) metabolites in various clinical conditions of probable VPA-associated hepatotoxicity. Epilepsia. 1993;34:332–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coulter DL. Carnitine, valproate, and toxicity. J Child Neurol. 1991;6:7–14. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell S. Carnitine as an antidote for acute valproate toxicity in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:206–210. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32805e879a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sztajnkrycer MD. Valproic acid toxicity: overview and management. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2002;40:789–801. doi: 10.1081/clt-120014645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson MA, Lynch S, Strong R, Shepherd RW, Marsh W. Orthotopic liver transplantation with poor neurologic outcome in valproate-associated liver failure: a need for critical risk-benefit appraisal in the use of valproate. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:200–203. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00936-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murayama K, Ohtake A. Children's toxicology from bench to bed--Liver Injury (4): Mitochondrial respiratory chain disorder and liver disease in children. J Toxicol Sci. 2009;34(Suppl 2):SP237–243. doi: 10.2131/jts.34.sp237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naviaux RK, Nguyen KV. POLG mutations associated with Alpers' syndrome and mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:706–712. doi: 10.1002/ana.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen KV, Ostergaard E, Ravn SH, Balslev T, Danielsen ER, Vardag A, McKiernan PJ, et al. POLG mutations in Alpers syndrome. Neurology. 2005;65:1493–1495. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000182814.55361.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen KV, Sharief FS, Chan SS, Copeland WC, Naviaux RK. Molecular diagnosis of Alpers syndrome. J Hepatol. 2006;45:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horvath R, Hudson G, Ferrari G, Futterer N, Ahola S, Lamantea E, Prokisch H, et al. Phenotypic spectrum associated with mutations of the mitochondrial polymerase gamma gene. Brain. 2006;129:1674–1684. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stewart JD, Horvath R, Baruffini E, Ferrero I, Bulst S, Watkins P, Fontana RJ, Day CP, Chinnery PF. POLG determines the risk of sodium valproate induced liver toxicity. Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.23891. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lheureux PE, Penaloza A, Zahir S, Gris M. Science review: carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity - what is the evidence? Crit Care. 2005;9:431–440. doi: 10.1186/cc3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lheureux PE, Hantson P. Carnitine in the treatment of valproic acid-induced toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009;47:101–111. doi: 10.1080/15563650902752376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]