Abstract

Most therapeutic agents used in clinical practice today were originally developed and tested in animal models so that drug toxicity and safety, dose-responses and efficacy could be determined. Retrospective analyses of preclinical intervention studies using animal models of different diseases demonstrate that only a small percentage of the interventions reporting promising effects translate to clinical efficacy. The failure to translate therapeutic efficacy from bench to bedside may be due, in part, to shortcomings in the design of the clinical studies; however, it is becoming clear that much of the problem resides within the preclinical studies. One potential strategy for improving our ability to identify new therapeutics that may have a reasonable chance of success in well-controlled clinical trials is to identify the most relevant mouse models IBD and pharmacologic strategies that most closely mimic the clinical situation. To begin this process, we present a critical evaluation of the different mouse models and pharmacological approaches that may be used in intervention studies as well as discuss emerging issues related to study design and data interpretation of preclinical studies.

Keywords: small molecules, therapeutics, biologics, cytokines, cell-based therapy, T-cells, regulatory T-cells, blood flow

Introduction

No single year generated more excitement within the inflammatory bowel disease community than did 1993. In October of that year, the journal Cell published three different studies demonstrating that ablation of the T-cell receptor, IL-2 or IL-10 gene resulted in the development of chronic colitis in these genetically-engineered mice(1-3). One month later, International Immunology published a study by Powrie and coworkers who reported that adoptive transfer of antigen inexperienced (naïve) CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells into lymphopenic mice induced a chronic and unrelenting colitis in the recipients(4). These four studies initiated a frenzy of research activity to determine how genetic alterations or immunological manipulations of very different molecular and cellular pathways could converge to produce a common disease phenotype. In many respects, these studies provided a much needed “jump-start” to what was, at that time, an active but relatively small research community investigating the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms responsible for the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). Indeed, virtually all experimental studies performed prior to 1993 used chemically-induced, self-limiting models of intestinal inflammation that were similar in concept to the animal models originally described by Kirsner and colleagues more than 50 years ago(5-7). The generation of genetically-engineered and immune-manipulated mice that developed chronic gut inflammation attracted large numbers of investigators from diverse scientific backgrounds who began to employ these new models to identify the immunopathogenetic mechanisms involved in chronic intestinal inflammation as well as define the pathways and cellular mediators responsible for tolerance and immune regulation. The number of investigators and the amount of information obtained using these models have grown unabated over the past seventeen years.

Currently there are more than 50 mouse models of intestinal inflammation with the large majority of these mice expressing acute or chronic colitis (Table 1)(8-14). A few of these mouse models have been characterized in sufficient detailed that they are beginning to be used in preclinical studies to test the efficacy of new drug therapies targeted for IBD. Historically, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies have not used disease-specific approaches for developing novel therapeutics to treat certain chronic inflammatory diseases choosing instead to develop “generic” anti-inflammatory medications to test in a variety of preclinical animal models of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), multiple sclerosis (MS) and IBD. Virtually all of the previous, and most of the current preclinical studies have relied heavily on the use of chemically-induced models of IBD. Although a reasonable approach given the simplicity and inexpensive nature of these erosive/self-limiting models, it is becoming increasingly apparent that some of these models are rather poor predictors of efficacy in chronic models of IBD and/or clinical trials. A quick survey of PubMed reveals that >1,000 studies have been published using the two most popular models of experimental colitis (e.g. dextran sulfate sodium and trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid models). Of these, more than 400 studies have reported significant protective or anti-inflammatory activity of novel small molecules, biologics, immune manipulations or genetic alterations. Yet, few if any of these potential “targets” or therapeutic agents have been evaluated in animal models of chronic intestinal inflammation. This is an important point to note because when attempted, few studies have been able to translate the promising anti-inflammatory activities of novel therapeutics observed in chemically-induced models to mouse models of chronic gut inflammation(15-19). Furthermore, the failure to translate preclinical data into clinically-effective medications is also becoming of increased concern. A good example of the disparity between preclinical studies and clinical efficacy can be found in the literature describing the development of the different leukotriene B4 receptor antagonists and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors for the treatment of various inflammatory disorders including IBD. Although these novel anti-inflammatory agents appeared to be quite promising in preclinical experiments using erosive models of colitis in rodents, investigators failed to demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory/protective effects in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) when evaluated in blinded, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical studies(20;21). Compounding the problems associated with the predictive value of certain preclinical models, is the fact that CD and UC are complex, multifactoral diseases that may not respond to anti-inflammatory or immune-modifying agents that are efficacious in autoimmune diseases such as RA or MS. The well-established anti-inflammatory activity of the soluble tumor necrosis-α (TNF-α) receptor antagonist entanercept (Enbrel) in human RA but not in CD highlights these complexities and the different pathogenetic mechanisms involved in these two chronic inflammatory disorders(22).

TABLE 1.

Representative Mouse Models of Small and Large Bowel Inflammation

| Acute/Self-Limiting Inflammation |

Chronic Inflammation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Induction | Immunological Induction |

T-Cell Transfer | Genetic | Spontaneous | Bacterial |

| DSS | CD40 mAb | CD45RBhigh→RAG (SB+C) | IL-2−/− | SAMPl/Yit (SB) | H. hepaticus |

| TNBS/EtOH | WT→CD3ε tg | IL-10−/− | C3H/HeJBr | ||

| Oxazolone/EtOH | TCR−/− | ||||

| Indomethacin (SB) | Gαi2−/− | ||||

| Mdrla−/− | |||||

| TNFΔARE (SB) | |||||

| STAT3−/− | |||||

| STAT4 tg | |||||

| CD40L tg | |||||

| A20−/− | |||||

| TGFβ1−/− | |||||

| N-Cadherin DN | |||||

| GPx 1&2−/− | |||||

| EP4−/− | |||||

| R59D-JAB tg (SOCS-1 tg) | |||||

| WASP−/− | |||||

| MUC2−/− | |||||

| IL10R2−/− × TGFβR DN | |||||

| IEC/IKK−/− | |||||

| Tbet−/− × RAG−/− (TRUC) | |||||

| CD4+/TGFβRII DN | |||||

| IL-7 tg | |||||

Compiled from references cited in the text. SB signifies mouse models expressing small bowel inflammation whereas SB+C designates small bowel and colonic inllammation. All other are models of colitis. tg=transgenic; DN=dominant negative.

It would seem clear that the “one size fits all” philosophy for drug development may not represent the best approach for developing new therapeutics targeted for IBD. If this is true, then what would be an alternative approach? One potential strategy for improving our ability to discover new therapeutics that may have a reasonable chance of success in well-controlled clinical trials is to identify the most relevant mouse models IBD and pharmacologic strategies that most closely mimic the clinical situation. Indeed, this type of strategy has been ongoing in the stroke community for more than 10 years(23;24). To begin this process, we present a critical evaluation of the different mouse models and pharmacological approaches that may be used in intervention studies as well as discuss emerging issues related to study design and data interpretation of preclinical studies.

Mouse Models of IBD

There are now several dozen mouse models of IBD that may be grouped into the acute/self-limiting and chronic models of small and/or large bowel inflammation(Table 1)(8-10;12). Because of the large number of mouse models expressing different types of inflammation in the small and/or large bowel, investigators are confronted with the daunting task of deciding which of these mouse models is/are appropriate to use for pharmacologic intervention studies. In reality, there is no single best model of IBD however the choice of an animal model should depend upon the specific questions being posed. Unfortunately, it appears that many of the pharmacological studies choose animal models based upon their simplicity, rapid onset of inflammation and expense. Therefore it is not surprising that the most popular models of intestinal inflammation are the acute, self-limiting models of colitis induced by rectal or oral administration of noxious polymers and/or organic acids.

Acute/Self-Limiting Models of Colonic Inflammation

The dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) model of acute/self-limiting colitis is by far, the most popular mouse model of IBD. Oral administration of this sulfated polysaccharide to rats, mice, hamsters or guinea pigs induces an acute colitis that is reminiscent of UC. Animals develop bloody diarrhea and weight loss over a period of several days depending upon the specific strain of animal(25). Histopathological inspection the colon reveals extensive infiltration of PMNs, monocytes and macrophages as well as frank ulcerations, goblet cell loss and occasional crypt abscesses(26-29). It is clear that much of the acute inflammatory response induced by oral administration of DSS arises from the nonspecific disruption or injury of the colonic epithelium. Although enteric bacteria have been suggested to contribute to gut pathology, other studies demonstrate that luminal bacteria play little role in DSS-induced inflammation and may actually play a protective role in this model(30-33). Exactly how DSS “injures” the epithelium is not known however it has been demonstrated that only specific molecular weights of DSS are able to induce colitis. For example, 5,000 MW DSS induces cecal inflammation and proximal colitis whereas the 40,000 MW polymer induces more distal bowel inflammation. Higher MW polymers (500,000 MW) do not induce colonic inflammation(34). These data suggest that smaller polymers of DSS may gain access to the baslolateral/intercellular space of the epithelium where they injure/disrupt the colonic epithelium. We propose, that the negatively charged sulfate residues may act to chelate or bind specific divalent cations (e.g. calcium and magnesium) that are required for maintaining normal epithelial cell tight junction integrity as well as for promoting epithelial cell-basement membrane attachment. The degree of sulfation of DSS is a critical determinant for inducing colonic inflammation(34). Because of significant differences in responses to DSS among the various mouse strains(25), the concentrations and/or time of exposure of DSS must be determined for each strain. In general, ad libitum administration of 2-5% DSS-containing drinking water induces diarrhea, rectal bleeding and weight loss within 4-8 days. Of note, DSS administration induces robust colitis in T- and B-cell deficient SCID or recombinase activating gene-1 (RAG-1−/−) mice demonstrating that the adaptive immune system plays no role in the pathogenesis of the inflammation(35;36). Not surprisingly, macrophage- and PMN-derived IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are increased in the inflamed colons in this model. Another interesting observation that has been made using this model is that DSS may interfere with colonic epithelial cell proliferation and mucosal repair by creating an “M1” inflammatory response(37). Infiltration and activation of macrophages with IFN-γ and/or LPS induces an M1 cytokine profile which is characterized by the production of large amounts of reactive oxygen and nitrogen metabolites as well as IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6. It has been suggested that one or more these inflammatory mediators directly or indirectly suppresses colonic mucosal barrier repair(37).

A second model of acute/self-limiting colitis that has been used by a number of different laboratories is the trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) model. This chemically-induced model was originally developed for use in rats(26); however, it has received wide-spread use for inducing colitis in mice over the past 10-15 years(27). Colonic inflammation is induced by the intrarectal administration of the hapten TNBS dissolved in 50% ethanol (EtOH). It has been proposed that EtOH is required to “break” the mucosal barrier thereby allowing TNBS to enter the colonic interstitium where it interacts with amino groups on colonic and possibly enteric bacterial proteins. This covalent modification or “haptenization” of colonic proteins is proposed to induce a localized, immunological response akin to the classical delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction. It should be noted however that only a few of the published studies using the TNBS/EtOH method actually perform an initial pre-sensitization with the hapten (ie skin painting) that is normally required to induce a classical DTH reaction(38). The immunological similarities and differences of colonic inflammation-induced in the absence or presence of prior sensitization have not been adequately investigated. It should be noted that neutralized solutions of TNBS (pH 7.4) in the absence of EtOH is in fact quite toxic to intestinal epithelial cells(28;37;39) In addition, we have found intrarectal administration of unbuffered TNBS dissolved in distilled water (pH 1.5) is sufficient to injure the mucosa and induce colitis in rats (unpublished data). Thus, the requirement for EtOH is not readily apparent. Nevertheless, this model does induce a Th1 (and possibly Th2) inflammation characterized by production of significant amounts of IL-2, INF-γ, TNF-α and IL-12 as well as by the infiltration of PMNs, macrophages and lymphocytes. A few studies have suggested that CD4+ T-cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of TNBS-induced colitis(40). This model has been useful in identifying different cytokines and inflammatory mediators responsible for leukocyte infiltration as well as mediators that appear to interfere with epithelial repair(9;41-43). It should be noted that the inflammation induced by intrarectal administration of TNBS/EtOH is highly dependent upon mouse strain thereby requiring a substantial amount of time to optimize concentrations and volumes of TNBS/EtOH in order to reproducibly induce robust colitis without significant mortality(38).

When one is evaluating the suitability of the DSS or TNBS models for use in pharmacologic studies, it is important to review a few of the basic tenets that have emerged from studies using these types of mouse models of IBD. First, it must be appreciated that oral or rectal administration of a damaging agent induces an acute, self-limiting inflammatory response via the nonspecific injury to the colonic epithelium. The magnitude of this initial insult cannot be modulated unless the concentration and/or delivery of the noxious chemical has been inadvertently altered. This seemingly obvious, yet frequently overlooked fact, has important ramifications when interpreting data from pharmacologic studies where a drug or intervention alters water consumption and/or enhance colonic fluid/bicarbonate secretion (see Pharmacological Approaches). Another important principle that has emerged from studies using these models is that certain pro-inflammatory mediators interfere with mucosal wound repair. It is becoming increasingly appreciated that PMN-, DC- and/or macrophage-derived cytokines/mediators interfere with normal epithelial cell reparative processes(37;41-46). Thus, any intervention that promotes epithelial cell restitution/proliferation and barrier repair or abrogates pathways that interfere with epithelial barrier repair will be observed as having “anti-inflammatory” activity in these erosive models(45-47). Indeed, these are the most likely mechanisms involved in the protective effects observed when leukocytes are prevented from migrating to the colonic interstitium or when specific inflammatory mediators are blocked or neutralized. A third important principle related to most, if not all of the chemically-induced models is that colonic inflammation may not require the adaptive immune system. There is no question that this is true for the DSS model(35;36); however, the role of the adaptive immune system in the conventional TNBS/EtOH model where a pre-sensitization protocol is not used, is somewhat more controversial. The evidence implicating CD4+ T-cells as important mediators of disease pathogenesis in this TNBS model is largely indirect and derived from studies demonstrating that ex vivo-activated lamina propria T-cells produce copius amounts of Th1 cytokines and that administration of mAbs directed toward IL-12, CD40L or IFN-γ attenuate TNBS/ETOH-induced colitis(10;48). In addition, it has been reported that colitis can be induced in healthy wild type mice by adoptive transfer of CD4+ T-cells obtained from the colons of TNBS/EtOH-treated mice with active colitis(40). Although compelling, these studies are difficult to interpret since the recipient animals were also exposed to luminal TNBS/EtOH. Furthermore, other laboratories have demonstrated that intrarectal administration of TNBS/EtOH to lymphopenic SCID or RAG-1−/− mice induces colonic inflammation that is histopathologically indistinguishable from that induced in wild type mice suggesting that lymphocytes are not required for the induction of colitis in this model(49). In one of the few studies where mice were pre-sensitized to TNBS via skin painting one week prior to intrarectal administration of TNBS/EtOH, it was found that colonic inflammation was reduced by approximately 50% in RAG−/− mice compared to wild type animals suggesting that lymphocytes may be important for some but not all of the inflammation induced in this variation of the conventional TNBS model(50). The reasons for these differences are not readily apparent but most probably reflect highly variable nature of this model as well as the different methods used for disease induction. Therefore, it is imperative that the investigator carefully consider and define mouse strain, concentrations of TNBS and/or EtOH and method for induction of colitis. Taken together, the literature suggest that despite their limitations, both the DSS and TNBS models are quite useful for evaluating novel therapeutics designed to promote epithelial restitution and proliferation as well as mucosal wound repair in the presence of an acute inflammatory response. Their usefulness for evaluating the role that the adaptive immune system plays in disease pathogenesis and/or drug efficacy appears to be limited.

The chemically-induced models have been promoted as animal models to study the role of the innate immune system in colonic inflammation. This is true for the most part, however, their requirement for a damaging agent to induce the colonic inflammation renders these models more susceptible to unanticipated effects of different drugs/therapeutics thereby leading to a misinterpretation of data (See Pharmacological Approaches). One model of acute/self-limiting colitis that does not require the use of noxious chemicals to induce colonic inflammation is the CD40 mAb model (Table 1)(51). Acute colitis can be induced in lymphopenic RAG-1−/− mice by a single injection (ip) of agonistic CD40 mAb. The mice develop rapid weight loss and diarrhea within the first 4 days with splenomegaly, hepatopathy and lymphadenomegaly of the mesenteric lymph nodes apparent by day 7. Histological inspection of the colons obtained from these mice at 7 days post mAb treatment reveals marked epithelial hyperplasia and extensive leukocyte (PMN, monocyte) infiltration within the lamina propria as well as goblet cell depletion, and epithelial cell destruction(51). Colitis persists for 10 days and is completely resolved by 3 weeks following treatment with the CD40 mAb. It is proposed that CD40 ligation initiates an inflammatory cascade that begins with the activation of different myeloid cells including dendritic cells (DCs) and monocytes to produce IL-23 and IL-12. These cytokines then promote the release of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-6 by DCs and macrophages as well as enhance the production of IFN-γ by natural killer cells(51). Thus, this model offers investigators an alternative model for studying the pathogenesis of innate immune cell-mediated colitis induced by an immunological manipulation rather than by administration of exogenous chemicals.

Mouse Models of Chronic Colitis

A major limitation in understanding the pathogenetic mechanisms responsible for the induction and perpetuation of chronic intestinal inflammation prior to the mid-1990s was the availability of rodent models that developed chronic intestinal inflammation. Although no single animal model completely recapitulates the clinical and histopathological characteristics of human IBD, a number of different mouse models of chronic small bowel and/or colonic inflammation have been developed over the past 15 years that have greatly advanced our understanding of disease pathogenesis (Table 1). Data obtained from a number of studies using a variety of different chronic models have revealed several recurring themes. First, chronic gut inflammation is mediated by T-cells. Second, commensal enteric bacteria drive gut inflammation by providing continuous antigenic and adjuvant stimulation. Third, defective immune-regulation promotes chronic inflammation and finally, the genetic background of the animal modulates disease onset, severity and phenotype. Taken together, these studies suggest that chronic intestinal inflammation develops as a result of a dysregulated immune response to components of the normal enteric flora(52-54). Thus, it is reasonable to propose that mouse models of chronic gut inflammation are in general, more relevant to human IBD than are acute/self-limiting models. Of the many models of chronic gut inflammation that have been developed, only a few of these models have been used by sufficient numbers of investigators to yield detailed information on the penetrance, severity and pathogenesis of the inflammation. Three models of chronic colitis that are readily available to all investigators are the T-cell transfer, IL-10-deficient (IL-10−/−) and multidrug resistance pump 1a-deficient (Mdr1a−/−) models (Table 1).

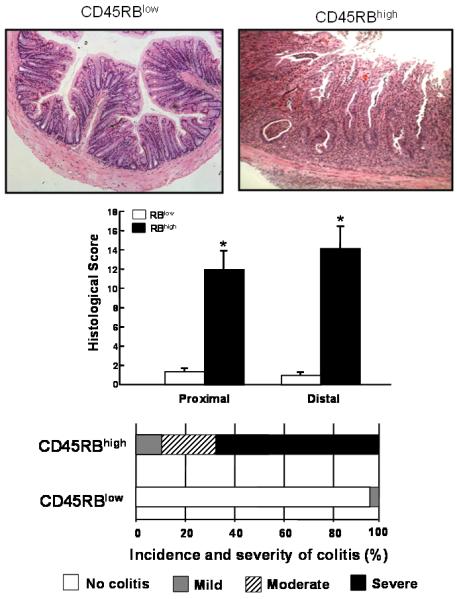

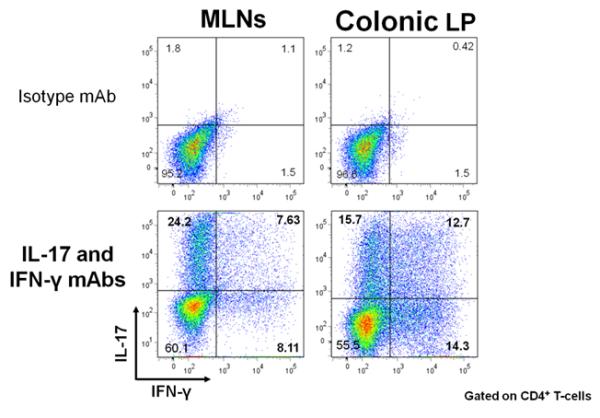

The prototypical and best-characterized model of chronic colitis induced by disruption of T-cell homeostasis is the CD45RBhigh T-cell transfer model(Table 1)(4;55). Adoptive transfer of antigen inexperienced (ie naïve) CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells from healthy wild type mice into syngeneic, lymphopenic recipients induces a chronic and unrelenting pancolitis at 5-8 weeks following T-cell transfer(Figure 1)(4;55;56). There is good evidence to suggest that in the absence of regulatory T-cells (Tregs; CD4+Foxp3+), naïve T-cells undergo enteric antigen-driven priming, polarization and expansion to yield large numbers of colitogenic effector cells such as Th1 and Th17 cells within the gut-draining mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and colon(4;53;55;56). Because naïve T-cells will, by default, convert to disease-producing effector cells in the absence of Tregs, virtually any T-cell deficient recipient (e.g. RAG-1−/−, RAG-2−/−, nude, SCID, CD3−/−, TCRβ−/− × TCRδ−/−, etc) can be used as recipients(53;55;57). We have found that Balb c SCID mice develop a slightly more rapid and severe form of colitis than do the C57Bl/6 RAG-1−/− mice. In addition, we have observed that the presence of B-cells delays modestly the onset but not severity of colitis supporting the concept that B-cells may act o suppress colonic inflammation in mice(56;58;59). Histopathological analysis of colons obtained from mice with active disease reveals transmural inflammation, epithelial cell hyperplasia, PMN and mononuclear leukocyte infiltration, occasional crypt abscesses and epithelial cell erosions (Figure 1). Depending upon the strain of the donor and recipient, reconstituted mice exhibit varying degrees of weight loss and diarrhea/loose stools. Historically, the T-cell transfer model has been described as a Th1 model of colitis because of the large increase in IFN-γ production within the inflamed tissue(56). However, we and others have found that the inflammation induced in this model represents a mixed Th1/Th17 inflammation because CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes and colonic lamina propria of colitic mice produce both cytokines (Figure 2). The major advantages of this model are that one can examine the earliest immunological events associated with the induction of gut inflammation as well as the time-dependent induction of disease. Furthermore, chronic colitis can be attenuated by treatment with a variety of different pharmacologic, immunologic, biologic and antibiotic treatment protocols (Table 2)(9;60-67). In addition, this model has been proven to be very useful to study the role that Tregs play in suppressing or limiting the onset and/or severity of colonic inflammation(68;69). Importantly, te Velde and coworkers have found, using genome-wide gene expression profiling of inflamed colons, that the pattern of gene expression in the CD45RBhigh T-cell transfer model most closely reflects the altered expression profile observed in human IBD when compared to the chemically-induced models of colitis(18).

Figure 1.

Adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells into RAG-1−/− recipients induces chronic colitis. Histopathological analysis of RAG-1−/− injected (ip) with 5×105 CD4+CD45RBlow (RBlow) or CD4+CD45RBhigh (RBhigh) T-cells. At 8 weeks following T-cell transfer, animals were euthanized and colonic inflammation was quantified by blinded histopathological analysis using our published scoring criteria(55). Reproduced from Ostanin et. al., Am. J. Physiol, 2009 (55) with permission from the Am. Phys. Soc

Figure 2.

Adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells into RAG-1−/− recipients induces a mixed Th1/Th17 colitis. Mononuclear cells from MLNs and colonic lamina propria (LP) of colitic mice at 8 weeks post T-cell transfer were activated in vitro, permeabilized and stained with isotype control or IL-17 and IFN-γ mAbs. Representative intracellular staining for the 2 cytokines within CD4+ cells is shown. Reproduced from Ostanin et. al., Am. J. Physiol, 2009 (55) with permission from the Am. Phys. Soc.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacological Studies Using Mouse Models of Chronic Gut Inflammation

| Model | Therapeutic | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| IL-10−/− | TNF/TNFR antisense | Yes |

| IL-6/IL-6R mAb | Yes | |

| IFNγ/IFNγR mAb | depends on timing |

|

| IL-12/1L-23 mAb | Yes | |

| CD45RBhigh→ SCID/RAG |

OX40L mAb | Yes |

| B7-H1 mAb | Yes | |

| CD70 mAb | Yes | |

| Anti-angiogenic peptide | Yes | |

| FTY 720 | Yes | |

| FasL mAb | No | |

| Dexamethasone/Prednisolone | Yes | |

| Azathioprine | No | |

| Su1fasalazine/5-ASA | No | |

| Cyclosporine | No | |

| Tacrolimus | No | |

| TNF/TNFR mAb | Yes | |

| Integrin mAbs (β7. MAC-1. LFA-1, α4) |

Yes | |

| IL-6/IL-6R mAb | Yes | |

| IFNγ/IFNγR mAb | Yes | |

| IL-12/IL-23 mAb | Yes | |

| TNFΔARE | Integrin mAb (β7) | Yes |

| TNF/TNFR mAb | Yes | |

| SAMP1/Yitc | Dexamethasone | Yes |

| TNF/TNFR mAb | Yes | |

| Integrin mAbs (β7, MAC-1, LFA-1, α4) |

Yes | |

| IL-6/IL-6R mAb | Yes | |

| IFNγ/IFNγR mAb | Yes | |

| IL-12/EL-23 mAb | Yes | |

| CCR9 mAb | Yes |

Compiled from references presented in the text.

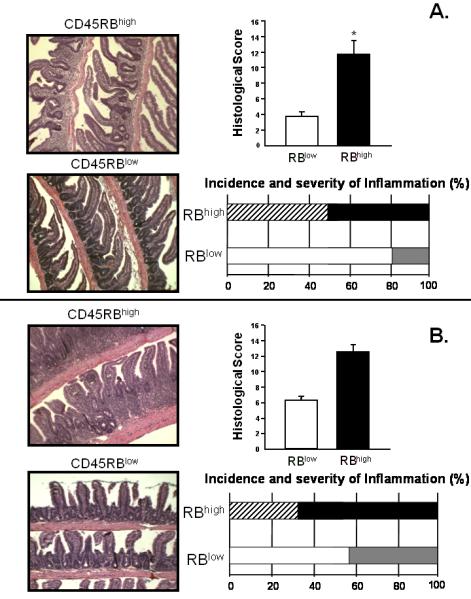

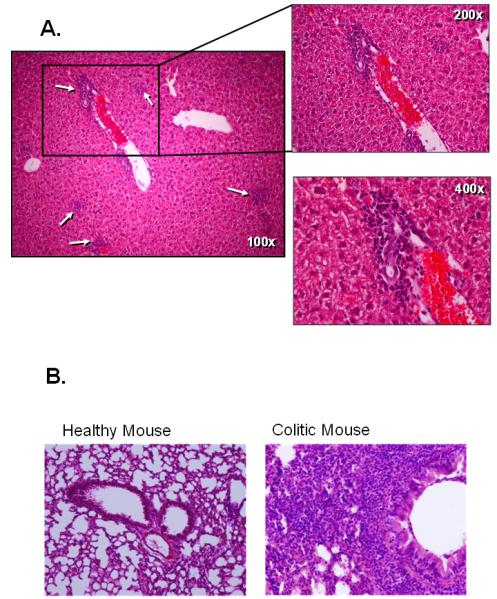

The original reports describing this model suggested that the inflammation was largely confined to the colon however more recent data demonstrates that the transfer of naïve T-cells into RAG-1−/− (or TCRβ−/− × δ−/−) mice induces both colitis and small bowel inflammation(Figure 3)(56;70;71). We and others have found that the small intestine of these reconstituted RAG-1−/− mice exhibited loss of Goblet and Paneth cells along the entire length of small intestine, which was most noticeable in the distal portion(56). This model may prove useful for investigators who wish to ascertain whether the immunological mechanisms responsible for colitis are similar to those that induce inflammation of the small intestine. The reasons for the relative paucity of reports by other laboratories describing small intestine inflammation in this model are not known however most of the original studies used SCID recipients whereas we have used RAG-1−/− mice. It is well-known that SCID mice are “leaky” in that they can begin to develop B-cells with age which may influence the development of intestinal inflammation. In addition to the small intestine, reconstitution of RAG-1−/− mice with naïve T-cells induces chronic liver and lung inflammation. We have observed extensive periportal and lobular lymphocytic inflammation, hepatocellular necrosis but no bile duct damage (Figure 4A)(55;72). In addition, we have found that virtually all colitic mice develop chronic bronchitis/pulmonary inflammation (Figure 4B)(72). In many cases (>60%) we observed confluent inflammation merged together between small and medium sized bronchi. Varying degrees of perivascular lymphocytic cuffing were also observed in virtually all of the mice however few PMNs were observed and vasculitis was absent.

Figure 3.

Histopathology, incidence and severity of jejunal (A.) and ileal (B.) inflammation in RAG-1−/− reconstituted with CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells or CD4+CD45RBlow T-cells. Note the villus blunting, bowel wall thickening and inflammatory infiltrate in the mice injected with CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells. Reproduced from Ostanin et. al., Am. J. Physiol, 2009 (55) with permission from the Am. Phys. Soc.

Figure 4.

Adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells into RAG-1−/− recipients induces chronic liver and lung inflammation. A. Histopathology of the liver. Note the periportal and intralobular inflammatory infiltrate composed primarily of mononuclear cells. Reproduced from Ostanin et. al., Am. J. Physiol, 2009 (55) with permission from the Am. Phys. Soc. B. Histopatholgoy of lungs obtained from healthy wild type or RAG-1−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells (8 wks post transfer). Virtually all colitic mice presented with chronic bronchitis/pulmonary inflammation with the majority of these animals exhibiting confluent inflammation merged together between small and medium sized bronchi (unpublished data)(72). Varying degrees of perivascular lymphocytic cuffing were also observed in most of the mice however few PMNs were observed and vasculitis was absent.

A second, widely-used model of chronic colitis is the IL-10−/− model. Mice with targeted disruption (i.e. deletion) of the IL-10 gene develop spontaneous pancolitis and cecal inflammation by 2-4 months of age(1;73). Histopathological analysis of colons obtained from mice with active disease show many of the same characteristics as those observed in human CD including transmural infiltration of mononuclear leukocytes, T-cells and plasma cells. The genetic background of the mouse is a major modifier of disease with disease penetrance and severity occurring to a much greater extent in 129SvEv IL-10−/− than in C57Bl/6 or Balb/c IL-10−/− animals. The advantage of using the IL-10−/− model is that it is a well-established Th1 model of transmural colitis and cecal inflammation that can be attenuated by administration of various pharmacologic, immunologic, biologic, antibiotic and probiotic agents (Table 2)(9). However, the onset and severity of disease is variable and in some cases requires many months to develop.

A third model of chronic colitis that is receiving increasing attention is the multidrug resistance pump 1a-deficient (Mdr1a−/−) mouse(74). Mdr1a is a P-glycoprotein expressed on the surface of several different cell populations including intestinal epithelial cells, T-cells, monocytes, macrophages, natural killer cells, dendritic cells and brain microvascular endothelial cells. This transport protein pumps small amphiphilic and hydrophobic molecules across the cell membrane in an ATP-dependent manner. Interestingly, Mdr1a−/− mice develop a moderate to severe colitis beginning at 12-15 weeks of age when housed under specific pathogen-free conditions(74). The colonic inflammation can be significantly reduced by administration of antibiotics demonstrating yet another model of IBD where inflammation is dependent upon the presence of commensal bacteria. Histopathological analysis of colons obtained from these mice reveals an inflammation that is similar in many respects to human UC. There is substantial thickening of the mucosa, extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lamina propria and occasional crypt abscesses and ulcerations. The mechanisms by which ablation of the Mdr1a gene induces chronic gut inflammation are not known at the present time however, it is known that the induction of colitis in these mice is dependent upon defective Mdr1a activity on the intestinal epithelial cells and not the lymphocytes(75). It may be that the lack of intestinal epithelial cell Mdr1 results in increased accumulation of enteric antigens within these cells. Antigen-loaded cells could then process and present these microbial antigens to T cells immediately underlying the epithelium thereby priming the T cells to become “hyper-reactive” to the enteric microbiota and drive colonic inflammation(74;75). More recent studies have demonstrated a significant dysregulation of expression of cytokines and chemokines prior to onset of colitis in young Mdr1a−/− mice. These data suggest that the intestinal immune system in these mice may be in a continuous state of immune activation and thus are particularly susceptible to induction of chronic gut inflammation(74). Another interesting aspect of this model is that mdr1a gene is located on chromosome 7q21.1 which is one of the chromosomes that has been shown to be associated with both CD and UC susceptibility(74).

The large majority of mouse models displaying chronic colitis require the participation of the adaptive immune system for expression of disease. However, recent evidence suggest that innate immune cell activation alone is capable of inducing and perpetuating chronic intestinal inflammation(51;76;77). For example, Maloy et. al have developed a mouse model of innate immune cell-mediated chronic colitis that is induced by associating lymphopenic RAG−/− animals with the Helicobacter hepaticus (Hp)(51;77). Although Hp does not normally induce chronic gut inflammation in healthy/immunocompetent mice, introduction of this gram negative, spiral bacterium into RAG−/− animals establishes a life-long colonization that ultimately induces chronic cecal and colonic inflammation (typhlocolitis)(51;76;77). This IL-23-driven inflammation is characterized by epithelial cell hyperplasia and extensive infiltration of PMNs and monocytes which is more severe in the cecum than in the colon(77;78). A recent variation of this model has been described in which chronic colitis can be induced in immunocompetent mice by combining the introduction of Hp with systemic administration of a mAb to IL10R(79-81). Another, interesting model of innate immune cell-driven chronic colitis was recently described by Garrett and coworkers(76). These investigators demonstrated that ablation of T-bet (a T-box transcription factor family member) in RAG−/− mice results in the development of spontaneous and communicable colitis that is similar to human UC. The colonic inflammation in these T-bet−/− × RAG-2−/− ulcerative colitis (TRUC) mice is characterized by remarkable PMN and monocyte inflammation, crypt abscesses, bowel wall thickening, erosions and ulcerations. These investigators also demonstrated colonic epithelial barrier disruption prior to the onset of active colitis. The fact that colitis is communicable and will develop in wild type mice when housed with TRUC mice suggest the selection of a colitogenic microbiota that develops in response to immune defects(76). This model may represent an important new addition to IBD investigators who wish to investigate relationship among the innate immune system, mucosal barrier function and chronic gut inflammation.

Models of Chronic Small Bowel Inflammation

In addition to the well-characterized models of chronic colitis, two models of spontaneous small bowel inflammation are gaining increasing interest for studying the immunopathology of Crohn’s ileitis as well as for evaluating new drug therapies. One model is the TNF-over-expressing TNFΔARE mouse. These mice were developed by targeted deletion of a 69 base pair region of the AU-rich elements in the 3′ UTR region of the TNF-α gene(82). The deletion results in increased TNF-α mRNA stability and enhanced TNF-α protein production. Mice possessing the deletion in the homozygous state (TNFΔARE/ΔARE) display severe and rapid wasting and die within 1-3 months of age. These mice are runted in appearance, exhibit alopecia-like lesions and develop chronic and degenerative inflammatory arthritis. Interestingly, there appears to be a gene dosage effect as heterozygote littermates (HET; TNFΔARE/ARE) develop a slower onset of disease and live at least 7-8 months. Histopathological analysis of the GI tract of both TNFΔARE/ΔARE and their HET littermates at 2-3 weeks of age reveals inflammation within the terminal ileum. Lesions consist of villous blunting (and broadening) associated with the transmural infiltration of acute and chronic inflammatory cells, including mononuclear leukocytes, plasma cells and PMNs. In general, severe ileitis is observed by 3 weeks of age in TNFΔARE/ΔARE mice and 8 weeks in the HETs. This transmural inflammation extends deep into the muscular layers of the bowel wall, displaying characteristics of Crohn’s ileitis. In fact, older mice (4–7 months of age) begin to display granulomatous lesions similar to what is seen in CD. The inflammation observed in this model can be treated with several biologics and immune-modifying drugs used in human medicine (Table 2). This model offers the unique opportunity to examine the immunopathological mechanisms underlying TNF-induced ileitis and arthritis with the possibility of identifying new therapeutic strategies to treat patients with CD.

The SAMP1/Yit model of chronic ileitis is another model that is gaining increasing popularity and is readily available to interested investigators. As with TNFΔARE/ΔARE mice, these animals are useful for studying the underlying mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s ileitis and preclinical evaluation of new drug therapies. This model of spontaneous ileitis was originally generated by >20 generations of brother–sister mating of a senescence-accelerated mouse line(83). SAMP1/Yit mice are unique in that 100% of these animals develop spontaneous ileitis at ~30 weeks of age without any genetic, immunological or environmental manipulation. Histopathological analysis of these mice reveal robust and chronic ileitis that is similar in many respects to human CD. The segmental inflammation is localized to the terminal ileum, displays transmural involvement and occasional granulomas. Chronic ileitis can be adoptively transferred by CD4+ T-cells to SCID or RAG−/− recipients suggesting that activated CD4+ T-cells may home specifically to and recognize antigens within the terminal ileum(84). Over the past few years, it was found that with further brother–sister matings for an additional 20 generations, a new phenotype emerged in which chronic ileitis developed by 10 weeks of age with the occurrence of perianal disease, ulceration and fistula in a small subset of these mice. This substrain has been renamed SAMP1/YitFc and has been propagated through continued brother–sister mating(85). Studies using the SAMP1/YitFc model have shown that immune-blockade of Th1- polarizing cytokines or certain T-cell adhesion molecules attenuate the severity of ileitis (Table 2). Thus, both the TNFΔARE/ΔARE and the SAMP1/YitFc mice provide the investigator with the unique ability to investigate the underlying immune-pathological mechanisms responsible for the development of ileal inflammation. An interesting yet perplexing observation that is common to virtually all mouse models of chronic small and/or large bowel inflammation is the lack of frank ulcerations with overt intestinal bleeding. The reasons for this are not known at the present time but are worthy of investigation. In summary, it is clear that at least 5 well-characterized mouse models of chronic small and/or large bowel inflammation are readily available for use in pharmacological studies.

Pharmacological Approaches: Concepts and Considerations

The selection of a mouse model that more closely mimics the immunopathology of CD or UC is an important first step for evaluating novel drug therapies targeted for IBD. An equally important decision to be made is the pharmacological approach that will be used to deliver the therapeutic agent. In order to identify the most appropriate method to deliver the drug that will provide the best indicator for clinical efficacy, it is important to discuss some basic pharmacologic concepts that bear directly on how and when therapeutic agents should be administered.

Bioavailability and Route of Administration

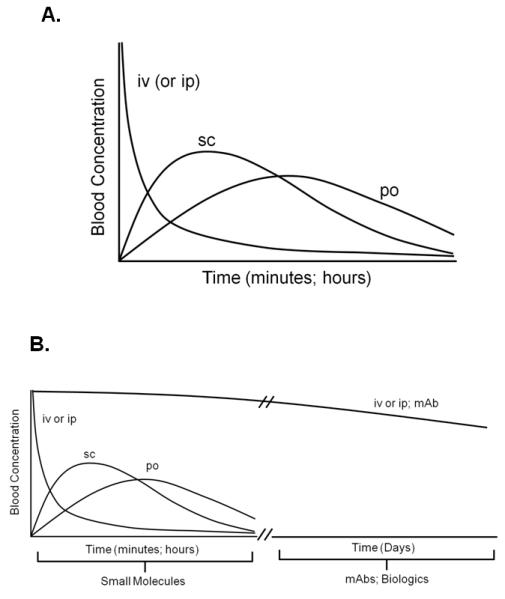

Bioavailability is a pharmacological term used to describe the fraction of an administered dose of drug (unchanged) that reaches its site of action or biological fluid from which the drug can access its site of action(86). Generally, the bioavailability of a drug is calculated from the time course of appearance of the drug in the systemic circulation (blood) which represents the sum of the processes of absorption, distribution and elimination of the therapeutic agent(86). Several factors influence the bioavailability including the physical properties of the drug (lipophilicity, size, solubility etc.), drug formulation, dose and route of administration. Although several options are available to the investigator for route of administration of a therapeutic agent, it is important to appreciate the advantages and limitations of these different routes especially if the compound is to be delivered over several days or weeks. Figure 5 illustrates how the route of administration affects the time course of drug concentration in the blood. Intravenous (iv) administration of a small molecule will produce a maximum blood concentration (Cmax) virtually instantaneously with its rate of disappearance dependent upon its rate of clearance and metabolic stability. Although a reasonable route of administration for acute studies, it would not be appropriate for dosing mice over a period of several days or weeks due to the increase risk of local (injection site) and systemic adverse reactions. Subcutaneous (sc) administration of this same drug will achieve Cmax within 15-20 minutes following injection. Indeed, this route of drug administration has been used for a variety of studies that require dosing of animals over many days or even weeks. Again, one must be aware of the limitations of chronic sc injections including limitations of injection volume as well as injection site necrosis and pain. It has been our experience that mice can be dosed (sc) daily for 6 weeks without inducing injection site necrosis provided that the injection site is alternated to different areas of the back and shoulders.

Figure 5.

Time course of drug concentration in blood. A. Time course of drug concentration in blood following intravenous (iv), intraperitoneal (ip), subcutaneous (sc) or oral (po) administration of a small molecule. B. Blood concentration-time curve for iv or ip administration of a monoclonal antibody (mAb; MW=150,000).

One of the least stressful routes of administration for chronic dosing of mice is oral (po) administration. There are several methods by which a drug may be delivered via this route. Orally administered drugs will generally achieve Cmax within 1-2 hours. Small molecules may be compounded with powdered chow and then ingested ad libitum; however, accurate determinations of drug delivery and dosing is tedious and time consuming. Alternatively, quantifiable delivery of a drug to the animal may be accomplished by intragastric gavage using commercially-available, silicone tipped gavage needles. We have found that mice can be gavaged with a small volume of vehicle or drug (0.25 ml) once per day for 6 weeks without any noticeable effects on the onset or severity of the colonic inflammation (data not shown). A cursory assessment of the literature reveals surprising few studies reporting therapeutic efficacy of novel small molecules when evaluated in mouse models of chronic intestinal inflammation. The reasons for this are not clear but may relate to the short circulating half-life (t1/2) of some small molecules and limitations for chronic dosing of the drug. Of course, it should always be remembered that targets and mechanisms controlled by a given target may be functionally different in mouse vs. human. One deliver system that can be used to deliver a known and constant amount of drug over a period of 1-2 weeks is by surgical implantation of osmotic pumps into the mice. The obvious limitations with this type of delivery system are the cost, host response to surgery, effects of surgery on gut inflammation and need to replace the pumps multiple times for chronic studies. Finally, it should be noted that the paucity of published studies reporting efficacy of small molecules in mouse models of IBD may simply represent failure to report negative data (see section on Study Design and Data Interpretation).

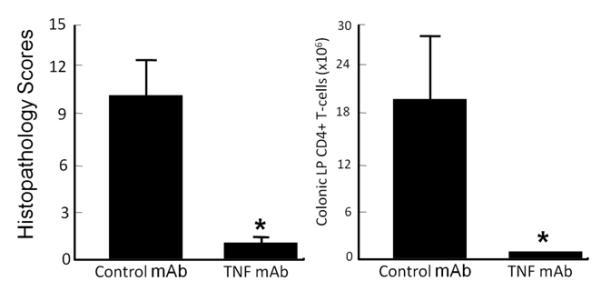

In contrast to the paucity of intervention studies using small molecules, there is a growing literature reporting some rather dramatic therapeutic effects of certain “biologics” in mouse models of chronic small and/or large bowel inflammation. Indeed, most of these studies report protective/anti-inflammatory activity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against specific cytokines, leukocyte adhesion molecules or lymphocyte accessory proteins(9). The significant protective effects of observed with specific mAbs may be related in part to their extended circulating t1/2 when administered iv or ip (Figure 5B). The t1/2 for proteins such as IgG possessing molecular weights of ~150,000 are in the order of several days thereby allowing for only once or twice weekly administration. This is clearly illustrated with biweekly administration (ip) of a mAb directed against mouse TNF-α (t1/2=4.6 days at 5mg/kg) over a period of 6-8 weeks (Figure 6). However, these biologics may be plagued with unwanted side effects, high cost and loss of efficacy over time.

Figure 6.

Administration of an anti-mouse TNF mAb attenuates chronic colitis. TNF mAb (Centocor) or an isotype control mAb was injected (ip) into RAG−/− mice beginning 2 wks following transfer of CD4+CD45RBhigh T-cells. Treatment continued biweekly (100 μg/injection) for 6 wks. At 8 wks, mice were euthanized, colons were removed for blinded histopathological and flow cytometric analyses.

Unanticipated Effects of Drugs

A major limitation with the use of the erosive (chemically-induced) models of colitis in pharmacological studies is their susceptibility to unanticipated effects by certain drugs. As discussed earlier, these models require luminal administration of a noxious agent to damage the colonic mucosa thereby inducing an acute inflammatory response. Thus, any situation that alters the delivery or effective concentration of the damaging agent will alter the inflammatory response(38;87). For example, if a drug inadvertently decreases water consumption in mice receiving DSS in their drinking water, the delivery/effective concentration of DSS will be reduced and thus the initial insult to the colonic mucosa will be decreased(87). This will result in less inflammation thereby leading the investigator to the erroneous conclusion that the drug possesses significant anti-inflammatory activity. Likewise, any drug that enhances colonic fluid/bicarbonate secretion will dilute and/or neutralize luminally-administered acids/solvents (e.g. TNBS/EtOH) and solvents (e.g. EtOH) thereby reducing the initial colonic injury and its subsequent inflammatory response. Therefore, it is critical to anticipate and account for these types of nonspecific effects. One of the best examples of how unanticipated pharmacological activities of certain drugs may affect the interpretation of data obtained in chemically-induced as well as chronic models of gut inflammation can be found in the nitric oxide (NO) literature. Numerous studies have been published demonstrating that chronic gut inflammation is associated with the upregulation of the inducible form of NO synthase (iNOS) and the sustained overproduction of NO(88). In addition, studies have demonstrated that administration of certain NOS inhibitors attenuated the gut inflammation observed in different models of acute and chronic colitis suggesting that NO is an important proinflammatory mediator(88;89). However, it soon became apparent that certain nonspecific NOS inhibitors were also potent vasoconstrictors due to their propensity to inhibit endothelial NOS (eNOS) as well as iNOS(89). Endothelial NOS-derived NO is a potent vasodilator that maintains proper vascular tone(90). These observations, coupled to well-known physiological principle dictating that delivery of inflammatory cells and mediators to tissue is a blood flow-dependent process, prompted a reevaluation of the original interpretation regarding the pathogenetic role of NO in acute and chronic inflammation. Indeed, much of the anti-inflammatory activity originally observed following administration of NOS inhibitors is now thought to be due to reductions in intestinal blood flow and the consequent decrease in delivery of inflammatory cells to the tissue(89). Finally, there is a growing appreciation of how a drug may alter the commensal enteric flora and thus may alter the induction and/or perpetuation of small bowel or colonic inflammation. As mentioned previously, the vast majority of chronic models require the presence of commensal bacteria to drive the intestinal inflammation. Even subtle alterations in enteric flora may have dramatic effects on the induction of disease in these mouse models. Thus, any drug that inadvertently reduces/alters the bacterial populations within the gut may be viewed as possessing anti-inflammatory activity.

Prophylactic vs Therapeutic Administration

One of the most important pharmacological decisions that can be made when attempting to mimic the clinical situation using animal models of disease, is the timing of administration of the therapeutic agent. The literature is full of examples reporting the beneficial effects of different therapeutics when administered prior to the onset of gut inflammation. In fact, the large majority of these studies use pretreatment protocols i.e. prophylactic administration of a therapeutic agents to test their ability to prevent or attenuate the induction of disease. Although an important first step for any pharmacological study, it is essential to follow up these studies with dosing protocols that treat established disease. However, few studies report the efficacy of novel therapeutics at reversing preexisting intestinal inflammation. We, as well as others contend that one of the best predictors of clinical efficacy of a drug is its ability to reverse established disease in at least two different animal models of chronic intestinal inflammation(91). A good example of how the timing of administration of a therapeutic agent in preclinical studies may be useful for predicting clinical efficacy (or lack thereof) can be found in the original studies investigating the efficacy of recombinant IL-10. A number of animal studies have demonstrated that exogenous IL-10 administration potently suppresses the induction of inflammation in both chemically-induced and chronic models of colitis. For example, it has been shown that the daily administration of IL-10 attenuates DSS- and TNBS/EtOH-induced colitis(92;93). Furthermore, daily injections of IL-10 prevented/attenuated the onset of chronic inflammation that develops in IL-10−/− and T-cell transfer models of chronic colitis in mice as well as in the peptidoglycan-polysaccharide-induced model of chronic granumolatous enteritis in rats(94-96). Given these dramatic protective effects using both acute and chronic models, there was great interest in testing this regulatory cytokine in patients with CD. Unfortunately, IL-10 administration was found to be ineffective when tested in randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trials in patients with active CD(97-99). At first glance these studies appeared to suggest that the preclinical data failed to translate to the clinic. However, when one revisits and critically evaluates the original animal studies, a different conclusion may be drawn. Although recombinant IL-10 was effective at preventing/attenuating induction of disease, it failed to attenuate preexisting colonic inflammation(73;96). Thus, it appears that the preclinical studies were in fact reliable predictors for the lack of effect of recombinant IL-10 in treating patients with active CD. This one example reinforces the importance of not only using a relevant model of human IBD but also emphasizes the need to replicate the pharmacological approach used to treat patients with CD or UC.

Study Design and Data Analysis: Lessons Learned from the Stroke Community

The IBD community is not alone in its efforts attempting to identify ways to facilitate the translation of preclinical data into new drug therapies. The stroke community has been dealing with this dilemma for more than 20 years. Greater than 1,000 drugs have been tested in a variety of rodent models of ischemic stroke with ~500 drugs or interventions reporting significant neuroprotective effects(100;101). And yet, only thrombolysis (tissue plasminogen activator; tPA) has been shown to significantly improve outcome when administered within 3 hours of stroke onset. Aspirin also possesses some neuroprotective activity, however it is much less effective than tPA and must be administered within 48 hours following stroke(101). Because of the abject failure to translate efficacy from bench to bedside, a group of investigators in both academia and industry convened a meeting more than 10 years ago to formulate recommendations for preclinical evaluation of potential neuroprotective drugs with the hope of identifying new therapeutic agents that may have a reasonable chance of success in appropriately designed clinical trials. The Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) published their consensus report in 1999 providing specific recommendations for preclinical development of acute stroke interventions(23). Unfortunately, during the intervening 10 years since the publication of the original recommendations, several more clinical trials have failed the bench to bedside progression for new drug therapies. This prompted the STAIR to meet and reevaluate the original recommendations in an effort to ascertain whether additional recommendations may be required to ensure “robust and reproducible” preclinical research with the hopes of identifying effective stroke therapies(24). The updated STAIR report reiterated support for the original recommendations as well as provided additional recommendations that included the elimination of randomization and assessment bias, a priori defining inclusion/exclusion criteria, performing power and sample size calculations, and disclosing conflicts of interest (Table 3)(24). These new recommendations arose in part, from several published studies that used systematic review and meta-analyses of data extracted from numerous reports demonstrating neuroprotection of different therapeutic agents in animal models of ischemic stroke. Statistical analyses of these studies revealed that the presence or absence of randomization of animals to the different treatment groups and blinding of drug assignment and/or outcome analyses represented the major determinants of drug efficacy(24;101-103). It was found that the efficacy of a drug was significantly and in some cases, dramatically lower in studies where animals were randomized into the different treatment groups prior to induction of stroke(24;102;103). Similarly, drug efficacy was found to be substantially less when drug assignment and/or outcome analysis were blinded(24;102;103). Indeed, only 36% of the preclinical stroke studies examined reported random allocation of animals with only 11% and 29% of these studies reporting allocation concealment or blinded outcome analyses, respectively(100;101).

TABLE 3.

Updated STAIR Recommendations for Preclinical Stroke Studies*

| Randomization | The method by which animals are allocated to the different groups should be described. |

| Sample Size Calculation | The method for how sample size of each group is calculated should be described. |

| Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | The criteria for including as well as excluding animals from data analyses should be described. All randomized animals should be accounted for in data presentation unless clearly delineated. |

| Allocation Concealment | The method for allocation concealment should be described. Allocation is concealed if the investigator responsible for the treatment and follow up care of animals is unaware of the treatment identity. |

| Blinded Assessment of Outcome | The assessment outcome is blinded if the investigator responsible for quantifying outcomes (e.g. histopathology) is unaware of animal treatment group. |

| Reporting Conilicts of Interest and Study Funding |

Presence or absence of any perceived conflict of interest should be reported. |

Table modified from Fisher et al. (24).

Another aspect of the experimental design that was viewed to be deficient in the large majority of preclinical studies was the reporting of power and sample size calculations. Although power analysis is critically important for calculating the minimum number of animals that are needed to identify significant differences between groups, it is almost never reported (or performed). The ability to identify significant differences between groups is related to the number of animals in each group, the expected differences between groups and the expected variance. However, systematic review of numerous preclinical studies reported that only 3% of the publications evaluated used any sort of power analysis(24;101). It should be noted that most federal and local funding agencies are now requesting that investigators perform a power analysis to determine the minimum number of animals required for their proposed experiments. Another problem associated with all preclinical studies (including experimental IBD) that is only now beginning to be addressed is publication bias. The large disparity between publications reporting significant drug efficacy vs. those reporting no effect or neutral results has been known for many years to be a major problem in the reporting of clinical trials however its impact in preclinical studies is only now beginning to be quantified(104). Recent work by Sena et. al. found that publication bias was highly prevalent in experimental stroke(104). Based upon their analyses, it was estimated that the published efficacy for several different drugs used in preclinical studies was overstated by at least 30% with the efficacy of some drugs inflated by more than 50%(104). In addition, these investigators determined that only 2% of the 525 publications analyzed reported no significant effects on infarct volume. Finally, Seno and coworkers estimated that at least one in seven experiments were completed but not published. Statisticians refer to this phenomenon as the “file drawer problem”(105). An extreme example of how this problem may create substantial publication bias is if one assumes that journals contain the 5% of studies performed that report significant results whereas 95% of the remaining studies that found no significant (ie neutral) effect remain in the file drawers of the investigators. The practice of publishing only positive-outcome data creates a misrepresentation of the data and clearly leads to erroneous conclusions with respect to drug efficacy. It is not hard to understand how this has happened when one realizes that “positive” data are much more likely to be published than are neutral data. In fact, one is hard pressed to find published, preclinical evaluations of new drug therapies reporting neutral data in the top-tiered journals. Publication bias is not unique to the experimental stroke community and undoubtedly exists in all animal studies attempting to translate preclinical data into new drug therapies(106).

Conclusions

Most therapeutic agents used in clinical practice were originally developed and tested in animal models so that drug toxicity and safety as well as dose-responses and efficacy could be determined. Retrospective analyses of preclinical intervention studies using different disease models demonstrate that few interventions/therapeutics reporting promising effects translate to clinical efficacy with only 10% of these therapeutic agents approved for use in patients(106;107). It is becoming increasingly recognized that the failure to translate therapeutic efficacy from bench to bedside may be due to significant deficiencies associated with the design of the preclinical studies. Many of these problem areas have been described in detail in the stroke literature; however it is clear that most of these same shortcomings exist in preclinical studies focused on IBD therapies. In order to facilitate and possibly even accelerate the development of new drug therapies targeted for use in IBD, it is imperative that the most relevant animal models, pharmacological strategies and study design be identified and used for preclinical intervention studies.

Acknowledgements

Some the of work reported in this manuscript was supported by a grant from the NIH (PO1-DK43785, Project 1, Animal Models Core and Histopathology Core). We would like to thank Drs. Beverly A. Moore and Dave Shealy (Johnson and Johnson, PRDUS) for their helpful comments.

Reference List

- 1.Kuhn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, et al. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mombaerts P, Mizoguchi E, Grusby MJ, et al. Spontaneous development of inflammatory bowel disease in T cell receptor mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:274–282. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, et al. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, et al. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C. B-17 scid mice. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1461–1471. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirsner JB, ELCHLEPP J. The production of an experimental ulcerative colitis in rabbits. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1957;70:102–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirsner JB, ELCHLEPP JG, GOLDGRABER MB, et al. Production of an experimental ulcerative “colitis” in rabbits. Arch Pathol. 1959;68:392–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraft SC, Fitch FW, Kirsner JB. HISTOLOGIC AND IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL FEATURES OF THE AUER “COLITIS” IN RABBITS. Am J Pathol. 1963;43:913–927. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:260–276. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell JR, Viney JL. Overview of mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease and their use in drug discovery. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2009;47:5.57.1–5.57.19. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0557s47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:514–521. doi: 10.1172/JCI30587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Mouse models of intestinal inflammation as tools to understand the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2021–2026. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JH, Weaver CT. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1327–1339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chidlow JH, Jr., Langston W, Greer JJ, et al. Differential angiogenic regulation of experimental colitis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2014–2030. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegmund B, Lehr HA, Fantuzzi G. Leptin: a pivotal mediator of intestinal inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2011–2025. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegmund B, Sennello JA, Lehr HA, et al. Development of intestinal inflammation in double IL-10- and leptin-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:782–786. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0404239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Te Velde AA, de KF, Sterrenburg E, et al. Comparative analysis of colonic gene expression of three experimental colitis models mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:325–330. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vowinkel T, Anthoni C, Wood KC, et al. CD40-CD40 ligand mediates the recruitment of leukocytes and platelets in the inflamed murine colon. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:955–965. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkey CJ, Dube LM, Rountree LV, et al. A trial of zileuton versus mesalazine or placebo in the maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. The European Zileuton Study Group For Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:718–724. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts WG, Simon TJ, Berlin RG, et al. Leukotrienes in ulcerative colitis: results of a multicenter trial of a leukotriene biosynthesis inhibitor, MK-591. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:725–732. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandborn WJ. Strategies for targeting tumour necrosis factor in IBD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:105–117. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.STAIR Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke. 1999;30:2752–2758. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40:2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahler M, Bristol IJ, Leiter EH, et al. Differential susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G544–G551. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.3.G544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris GP, Beck PL, Herridge MS, et al. Hapten-induced model of chronic inflammation and ulceration in the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:795–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, et al. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada Y, Marshall S, Specian RD, et al. A comparative analysis of two models of colitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1524–1534. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91710-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okayasu I, Hatakeyama S, Yamada M, et al. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukata M, Michelsen KS, Eri R, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 is required for intestinal response to epithelial injury and limiting bacterial translocation in a murine model of acute colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1055–G1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hans W, Scholmerich J, Gross V, et al. The role of the resident intestinal flora in acute and chronic dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:267–273. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitajima S, Morimoto M, Sagara E, et al. Dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in germ-free IQI/Jic mice. Exp Anim. 2001;50:387–395. doi: 10.1538/expanim.50.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, et al. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitajima S, Takuma S, Morimoto M. Histological analysis of murine colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium of different molecular weights. Exp Anim. 2000;49:9–15. doi: 10.1538/expanim.49.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dieleman LA, Ridwan BU, Tennyson GS, et al. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis occurs in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1643–1652. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90803-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieglstein CF, Cerwinka WH, Sprague AG, et al. Collagen-binding integrin alpha1beta1 regulates intestinal inflammation in experimental colitis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1773–1782. doi: 10.1172/JCI200215256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seno H, Miyoshi H, Brown SL, et al. Efficient colonic mucosal wound repair requires Trem2 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:256–261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Te Velde AA, Verstege MI, Hommes DW. Critical appraisal of the current practice in murine TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:995–999. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000227817.54969.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grisham MB, Volkmer C, Tso P, et al. Metabolism of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid by the rat colon produces reactive oxygen species. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:540–547. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90036-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, et al. Experimental granulomatous colitis in mice is abrogated by induction of TGF-beta-mediated oral tolerance. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2605–2616. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han X, Ren X, Jurickova I, et al. Regulation of intestinal barrier function by signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b. Gut. 2009;58:49–58. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pereira-Fantini PM, Judd LM, Kalantzis A, et al. A33 antigen-deficient mice have defective colonic mucosal repair. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:604–612. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson A, Keely S, Karhausen J, et al. Mucosal protection by hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibition. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:145–155. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edelblum KL, Washington MK, Koyama T, et al. Raf protects against colitis by promoting mouse colon epithelial cell survival through NF-kappaB. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:539–551. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frey MR, Edelblum KL, Mullane MT, et al. The ErbB4 growth factor receptor is required for colon epithelial cell survival in the presence of TNF. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:217–226. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, et al. Antibodies to interleukin 12 abrogate established experimental colitis in mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1281–1290. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fiorucci S, Mencarelli A, Palazzetti B, et al. Importance of innate immunity and collagen binding integrin alpha1beta1 in TNBS-induced colitis. Immunity. 2002;17:769–780. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Lierop PP, de HC, Lindenbergh-Kortleve DJ, et al. T-cell regulation of neutrophil infiltrate at the early stages of a murine colitis model. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:442–451. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uhlig HH, McKenzie BS, Hue S, et al. Differential activity of IL-12 and IL-23 in mucosal and systemic innate immune pathology. Immunity. 2006;25:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng T, Wang L, Schoeb TR, et al. Microbiota innate stimulation is a prerequisite for T cell spontaneous proliferation and induction of experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1321–1332. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powrie F. T cells in inflammatory bowel disease: protective and pathogenic roles. Immunity. 1995;3:171–174. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powrie F, Read S, Mottet C, et al. Control of immune pathology by regulatory T cells. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;252:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ostanin DV, Bao J, Koboziev I, et al. T cell transfer model of chronic colitis: concepts, considerations, and tricks of the trade. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G135–G146. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90462.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ostanin DV, Pavlick KP, Bharwani S, et al. T cell-induced inflammation of the small and large intestine in immunodeficient mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G109–G119. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00214.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanai T, Kawamura T, Dohi T, et al. TH1/TH2-mediated colitis induced by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD45RBhigh T lymphocytes into nude mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:89–99. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000197237.21387.mL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Takedatsu H, et al. Chronic intestinal inflammatory condition generates IL-10-producing regulatory B cell subset characterized by CD1d upregulation. Immunity. 2002;16:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mizoguchi E, Mizoguchi A, Preffer FI, et al. Regulatory role of mature B cells in a murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Int Immunol. 2000;12:597–605. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hirano D, Kudo S. Usefulness of CD4+CD45RBhigh. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:169–181. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08293fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dan N, Kanai T, Totsuka T, et al. Ameliorating effect of anti-Fas ligand MAb on wasting disease in murine model of chronic colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G754–G760. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00071.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujii R, Kanai T, Nemoto Y, et al. FTY720 suppresses CD4+CD44highC. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G267–G274. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00496.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanai T, Totsuka T, Uraushihara K, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 suppresses the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;171:4156–4163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leon F, Contractor N, Fuss I, et al. Antibodies to complement receptor 3 treat established inflammation in murine models of colitis and a novel model of psoriasiform dermatitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:6974–6982. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Z, Geboes K, Colpaert S, et al. Prevention of experimental colitis in SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells by blocking the CD40-CD154 interactions. J Immunol. 2000;164:6005–6014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manocha M, Rietdijk S, Laouar A, et al. Blocking CD27-CD70 costimulatory pathway suppresses experimental colitis. J Immunol. 2009;183:270–276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Totsuka T, Kanai T, Uraushihara K, et al. Therapeutic effect of anti-OX40L and anti-TNF-alpha MAbs in a murine model of chronic colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G595–G603. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00450.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]