Abstract

Objective

The aim of our prospective study was to assess the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of children with mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and the impact of clinical symptoms on HRQOL.

Methods

Sixty-seven patients with primary MVP aged 8–18 years were studied and compared with 31 healthy children. All children completed the polish version of KIDSCREEN-27. For searching occurrence and frequency of 18 clinical symptoms, authors’ questionnaire was used.

Results

The statistically significant difference was found only for one from five searching dimensions of HRQOL—physical well-being. In the remaining studied aspects of HRQOL, no statistically significant differences were found in comparison with the healthy children. The statistically significant moderate correlation between the number and frequency of clinical symptoms and physical well-being was found.

Conclusions

In children with MVP, the lower self-assessment is observed mainly in evaluation of their health and own physical activity. The remaining studied dimensions of HRQOL are comparable with the healthy children. However, within the population of children suffering from MVP, the frequency of clinical symptoms impact upon the different HRQOL dimensions. Thus, MVP represents a heterogeneous population. Whether there are impairments of HRQOL largely depend on the severity and frequency of clinical symptoms.

Keywords: Mitral valve prolapse, Quality of life, Children, KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire

Introduction

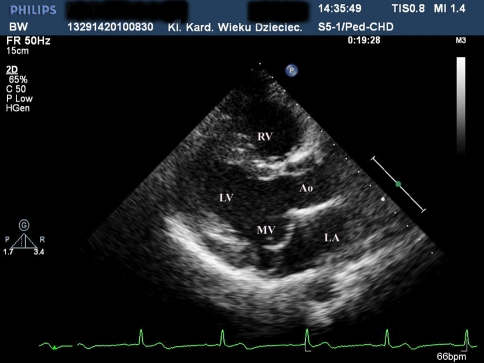

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is the most common heart defect in population. The prevalence of MVP is about 0.6–2.5%. The occurrence increases with age, and the highest is in young woman. MVP is diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiography when displacement of mitral valve leaflet(s) above the annulus into the left atrium during a systole is present (Fig. 1). The clinical symptoms of the disease are connected with instability of the autonomic nervous system.

Fig. 1.

Two-dimensional echocardiographic long axis parasternal view of mitral valve prolapse. MV mitral valve, LV left ventricle, LA left atrium, RV right ventricle, Ao aorta

Such a large population of patients becomes a problem of social significance, and it is extremely important to determine the influence of MVP as a chronic disease on patients. That is why our trial to evaluate the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children with MVP was undertaken.

There are many publications concerning MVP in adult patients, but no study on their quality of life has been found. The literature concerning HRQOL of children with heart defects is not very extensive; the authors analyzed the problem of patients with serious conditions, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, transposition of the great arteries, pulmonary atresia, tetralogy of Fallot and non-complex heart defects, like ventricular or atrial septal defect [1–3].

The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of life of children with MVP and the impact of clinical symptoms on HRQOL.

Methods

The prospective study (with the Institutional Bioethical Committee approval) included 67 subsequent patients with MVP, 47 girls and 20 boys aged 8–18 years (average 13.9 ± 2.61 years) and 31 healthy volunteers as a control group matched for sex and age with the study group. All patients with MVP were in NYHA class I. Mitral regurgitation was recorded in 63 children, grade I in 48, II in 11, III in 4. In all patients, sinus rhythm in ECG and in 19 patients, arrhythmia (11 supraventricular, 8 ventricular) in Holter ECG were found. Six patients were on beta-blockers. Diagnostic work-ups included anamnesis, 2D-echocardiography, authors’ questionnaire concerning clinical symptoms and KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire (polish version for kids 8–18 years) [4, 5]. KIDSCREEN-27 comprises 27 questions measuring five dimensions: physical well-being (5 questions concerning the sense of health, the level of a child’s physical activity, vital energy and fitness), psychological well-being (7 questions regard positive emotions, moods and life satisfaction), parents and autonomy (7 questions examining: relationships between children and parents, the atmosphere at home, the sense of self-determination and satisfaction with the financial status), peers and social support (4 questions evaluate the child’s relations), school environment (4 questions explore a child’s cognitive skills, mental concentration capability and school emotions).

Each question had 5 possible responses judging by the intensity of an attitude, e.g. not slighty/moderately/commonly/very/extremely or by the frequency never/seldom/sometimes/often/always.

MVP was diagnosed according to AHA/ACC guidelines [6, 7].

A questionnaire of 18 clinical symptoms: chest pain, heart palpitation, vertigo, collapse, fainting, dyspnea, headache, anxiety attacks, panic attacks, sudden mood changes, fatigue, concentration difficulties, decreased exercise tolerance, oral dryness, cold drenching sweats, gastrointestinal ailments, sleep disorders, disposition to depression was applied. The number and frequency of symptoms (every day/every week/every month/every 3 months) were assessed.

For quality measures, the frequencies of their occurrence and errors were determined on the basis of the binomial distribution. The results were compared with the modified t-test. Analyzing the nuisance of the studied symptoms, the cumulative frequency of their prevalence was determined starting from their everyday frequency and proceeding to the next coded frequencies. Linear correlation coefficients were calculated for series of dependencies. Sum scores per scale were calculated and transformed into values between 0 (worst) and 100 (best possible response pattern). Correlations were calculated for the study group for different frequency occurrences of clinical symptoms. Straight lines were fitted by the method of least squares with diagnosed MVP.

Results

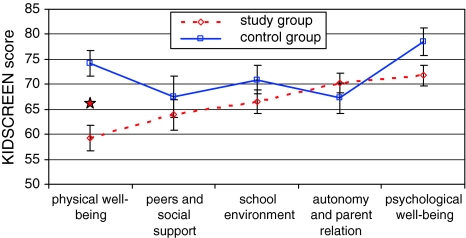

Mean scoring obtained in each of the five parts of KIDSCREEN questionnaire is presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between the study and control groups were found in the dimension of physical activity and health to disadvantage of children with MVP in comparison with healthy children (mean scoring, respectively, 59.2; 74.2). The differences in psychological well-being were close to statistically significance.

Table 1.

Results of KIDSCREEN scoring of children with mitral valve prolapse and controls

| Children with MVP | Control group | P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | ||||

| Physical well-being | 10 | 100 | 59.2 | 21.3 | 35 | 95 | 74.2 | 14.5 | 0.001 |

| Peers and social support | 0 | 100 | 63.9 | 25.6 | 25 | 100 | 67.6 | 23.0 | 0.503 |

| School environment | 6 | 100 | 66.5 | 20.0 | 44 | 100 | 70.9 | 15.7 | 0.278 |

| Autonomy and parent relation | 29 | 100 | 70.2 | 16.1 | 25 | 96 | 67.3 | 16.9 | 0.414 |

| Psychological well-being | 7 | 96 | 71.8 | 16.7 | 25 | 100 | 78.5 | 15.3 | 0.061 |

Fig. 2.

Mean scoring obtained in KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire

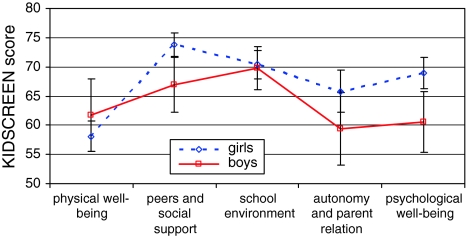

Correlation between age and dimensions of KIDSCREEN in the study group revealed r ranged from −0.02 to −0.29 when abs(r) >0.2 was statistically significant with P < 0.05 (Table 2). Age had a major influence on the evaluation of psychological well-being, autonomy and parent relation and school environment by children with MVP. No statistical differences of the results between girls and boys were found (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Correlation (r) between age and dimensions studied in KIDSCREEN questionnaire in the study group

| Physical well-being | Psychological well-being | Autonomy and parent relation | Peers and social support | School environment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.18 | −0.25 | −0.21 | −0.02 | −0.29 |

Fig. 3.

Results of KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire for boys and girls in the study group

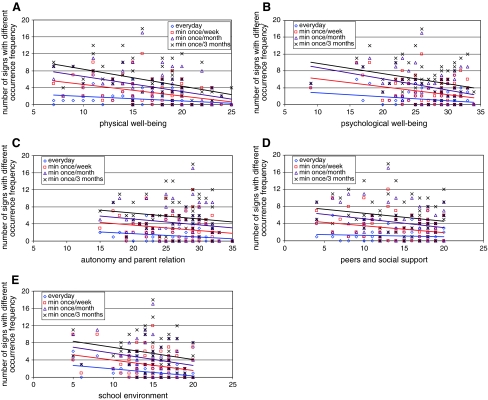

The statistically significant moderate correlation was found between the nuisance (number and frequency) of symptoms and physical well-being in the study group (r −0.27 to −0.44; P 0.01–0.001) (Fig. 4a). The correlation coefficients between the nuisance of symptoms and HRQOL were: for psychological well-being, r −0.26 to −0.35, autonomy and parent relation r −0.16 to −0.21, peers and social support r −0.08 to −0.24, school and environment r −0.24 to −0.31 (Fig. 4b–e).

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the nuisance (number and frequency) of analyzed clinical symptoms and all KIDSCREEN-27 dimensions (a physical well-being, b psychological well-being, c autonomy and parent relation, d peers and social support, e school environment). Straight lines fitted by the method of least squares represent correlations (r)

Discussion

The research on quality of life in various groups of patients reveals the scale of a problem, allows to identify the limitations of disease, needs and problems of patients and enables to achieve comprehensive medical care and multidisciplinary approach.

The results of published studies showed that children with congenital heart disease have problems in various HRQOL domains. Uzark et al. [8] found that one in five children with cardiovascular disease reports significantly impaired psychosocial quality of life, including children with mild or surgically corrected heart defects. Available results of studies analyzing the impact of severity of disease on HRQOL are discrepant. Arafa et al. [9] revealed that severity of illness and type of heart defect were associated significantly with poorer HRQOL. Contrary to the study by Krol et al. [10] showed that HRQOL in children with congenital heart disease was not influenced by severity of disease. Similarly, DeMaso et al. [11] found a lack of significant relationship between the severity of congenital heart defect and quality of life.

Our analysis of KIDSCREEN-27 results revealed lower self-assessment of quality of life of children with MVP in all investigated dimensions, except for parent and autonomy. However, the result differences were statistically significant only for health and own physical activity evaluation. Comparing the results of quality-of-life evaluation between girls and boys within the study group, no statistically significant difference was obtained. Bissegger et al. [12] studying 3,710 participants aged between 9 and 17 years from seven European countries proved that there is a correlation between the quality-of-life assessment and age and sex. Younger children assessed their quality of life higher, while over 12 years of age, this self-evaluation deteriorated in most dimensions, and this relation was more distinct for girls than for boys. It is believed that HRQOL is higher in children than in adults [13, 14]. It should be pointed out that there are also cultural and social issues resulting in differences in QOL studies from various countries [15].

Diagnoses of any heart defect cause anxiety and can induce symptoms. Despite MVP appearing to be a mild congenital heart anomaly in most children and prognoses well, children and parents are fearful. Our research reveals the importance of the study on HRQOL and cooperation between physicians and patients as well as comprehensive information.

Marino et al. [16] compared opinions of children with heart defects, their parents and doctors. They pointed out different domains of HRQOL, which were influenced by the disease.

In this research, correlation between the higher number and frequency of clinical symptoms prevalence and lower physical well-being was found. We observed weaker, but also negative correlations between the number and frequency of symptoms and the remaining dimensions. The better self-evaluation of the quality of life in children with MVP in every analyzed aspect was related to the lower number and occurrence of clinical symptoms. However, it needs to be emphasized that the studied group comprises patients with frequent and numerous symptoms, who assessed their health condition as good or very good. A question needs to be asked why children with similar symptoms evaluate their quality of life so discordantly. The low intensity of symptoms, the fact that children interested in the surroundings pay small attention to disease or they are capable to adjust to experienced symptoms and function well despite of them, should be considered. The attitude of adults also plays an important role in this issue. If a child after comprehensive tests is ascertained by a doctor that the prognosis of the heart defect is good and parents do not treat their child with exaggerated over-protectiveness, then the child feels safe and deals with the symptoms much better.

Conclusions

In children with MVP, the lower self-assessment is observed mainly in evaluation of their health and own physical activity. The remaining studied dimensions of quality of life are comparable with the healthy children. However, within the population of children suffering from MVP, the frequency of clinical symptoms impacts upon the different HRQOL dimensions. Thus, MVP represents a heterogeneous population. Whether there are impairments of HRQOL largely depend on the severity and frequency of clinical symptoms.

Study limitations

The study group consisted of subsequent patients referred to the cardiologist due to various reasons (e.g. heart murmur, symptoms, control visits, athletes screening), in whom the diagnosis of MVP was established. Therefore, the group does not represent the whole population of children with MVP. Epidemiologic population study would be of great value for generalization of the results.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- HRQOL

Health-related quality of life

- MVP

Mitral valve prolapse

- AHA/ACC

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology

References:

- 1.Mellander M, Berntssin L, Nilsson B. Quality of life in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Acta Pediatrica. 2007;96:53–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldbeck L, Melches J. The impact of the severity of disease and social disadvantage on quality of life in families with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiology in the Young. 2006;16:67–75. doi: 10.1017/S1047951105002118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekman-Joelsson BM, Berntsson L, Sunnegardh J. Quality of life in children with pulmonary atresia and intact ventricular septum. Cardiology in the Young. 2004;14:615–621. doi: 10.1017/S1047951104006067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravens-Sieberer U, Gosch A, Erhart M, et al. The KISDSCREEN questionnaires. Quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents. Handbook. Lengerich, DC: Pabst Science Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robitail S, Ravens-Sieberer U, Simeoni MC, et al. Testing the structural and cross-cultural validity of the KIDSCREEN-27 quality of life questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:1335–1345. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines from the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006;114:84–231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2008;118:e573–e576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uzark K, Jones K, Slusher J, et al. Quality of life in children with heart disease as perceived by children and parents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1060–1067. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arafa MA, Zaher SR, El-Dowaty AA, et al. Quality of life among parents of children with heart disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2008;6:91. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krol Y, Grootenhuis MA, Destree-Vonk A, et al. Health related quality of life in children with congenital heart disease. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:251–260. doi: 10.1080/0887044021000058076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMaso DR, Beardslee WR, Silbert AR, et al. Psychological functioning with cyanotic heart defects. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1990;11:289–294. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199012000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisegger C, Cloetta B, von Rueden U, et al. Health-related quality of life: Gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Sozial- und Präventivmedizin. 2005;50:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s00038-005-4094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravens-Sieberer U, Görtler E, Bullinger M. Subjective health and health behavior of children and adolescents–a survey of Hamburg students within the scope of school medical examination. Gesundheitswesen. 2000;62:148–155. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-10487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simeoni MC, Auquier P, Antoniotti S, et al. Validation of a French Heath-related quality of life instrument for adolescents: The VSP-A. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9:393–403. doi: 10.1023/A:1008957104322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robitail S, Simeoni MC, Ravens-Sieberer U, et al. Children proxies’ quality-of-life agreement depended on the country using the European KIDSCREEN-52 questionaire. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marino B, Tomlinson R, Drotar D, et al. Quality-of-Life concerns differ among patients, parents, and medical providers in children and adolescents with Congenital and Acquired Heart disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123:708–715. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]