Abstract

SMAD4 is localized to chromosome 18q21, a frequent site for loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in advanced stage colon cancers. Although Smad4 is regarded as a signaling mediator of the TGFβ signaling pathway, its role as a major suppressor of colorectal cancer progression and the molecular events underlying this phenomenon, remain elusive. Here, we describe the establishment and use of colon cancer cell line model systems to dissect the functional roles of TGFβ and Smad4 inactivation in the manifestation of a malignant phenotype. We found that loss of SMAD4 and retention of intact TGFβ receptors could synergistically increase the levels of VEGF, a major pro-angiogenic factor. Pharmacological inhibition studies suggest that overactivation of the TGFβ-induced MEK-Erk and p38-MAPK auxiliary pathways are involved in the induction of VEGF expression in SMAD4 null cells. Overall, SMAD4 deficiency was responsible for the enhanced migration of colon cancer cells with a corresponding increase in MMP9, enhanced hypoxia-induced GLUT1 expression, increased aerobic glycolysis and resistance to 5′-fluoruracil-mediated apoptosis. Interestingly, Smad4 specifically interacts with HIF1α under hypoxic conditions providing a molecular basis for the differential regulation of target genes to suppress a malignant phenotype. In summary, our results define a molecular mechanism that explains how loss of the tumor suppressor Smad4 promotes colorectal cancer progression. These findings are also consistent with targeting TGFβ-induced auxiliary pathways, such as MEK-ERK, p38-MAPK and the glycolytic cascade, in SMAD4-deficient tumors as attractive strategies for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Smad4, Chromosome 18q21, LOH, VEGF, GLUT1, colon cancer

Introduction

Colon cancer is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, accounting for more than 50,000 cancer deaths per year (1). There has been significant progress in understanding the familial predisposition to colon cancer and it has been exploited as an excellent model to understand the multi-step progression of human cancer (2, 3). On the other hand, since the majority of colon cancer cases are of sporadic origin and often diagnosed at an advanced stage, it remains a major form of cancer fatality. There has been little progress made in elucidating the molecular basis for the conversion of a benign form of the cancer to a more malignant and metastatic form, which accounts for the majority of colon cancer deaths. Thus, the delineation of the key genetic and epigenetic alterations that promote malignancy of colon cancer is important not only for prognosis and clinical surveillance of affected individuals but also for devising treatment strategies to block the dissemination of cancer cells and effectively eradicate tumors.

Resistance to growth inhibition by TGFβ is common in a variety of human cancers, emphasizing the importance of intracellular pathways mediated by this polypeptide to the neoplastic process (4, 5). Early investigations to understand the molecular basis of this resistance were concentrated at the level of TGFβ receptors and uncovered, lack of expression (6–8) and inactivation by point mutations of the TGFβ receptor type II (RII) (9–11). Subsequently, evidence for TGF-β receptor type I (RI) mutations was also reported (12). A major breakthrough in understanding the genetic basis of TGFβ insensitivity to growth emerged with the isolation of the SMAD4 gene as a target tumor suppressor gene localized to frequent homozygous deletions affecting 18q21.1 in pancreatic carcinomas (13). Since LOH at chromosome 18q has long been established as a late event during colon cancer progression (2), our studies were the first to report that SMAD4 mutations or deletions occurred in 30% of colon cancers that exhibited loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for chromosome 18q (14). Additional confirmations in numerous follow up studies also showed that a high frequency of LOH at 18q was associated with an increase in the frequency of SMAD4, and less frequently SMAD2 or DCC mutations (14–17).

When tumors corresponding to different stages of colon cancer were intrerrogated for SMAD4 inactivation arising from deletions or point mutations, there was a strong correlation between the higher frequency of SMAD4 gene mutations and distant metastases relative to non-metastatic forms of colon cancer (14, 15, 18–21). Additional credence was also derived from studies with mouse models where a dramatic increase in malignant progression of intestinal polyps in cis-compound heterozygotes [i.e., APC(+/−) SMAD4 (+/−) compared to the simple APC (+/−) heterozygotes] was observed (22, 23). Overall, studies using both human tumors and animal models corroborated the notion that disabling TGFβ signaling pathway at the level of Smad4 may be a critical late event in multi-step colon cancer progression.

Here we provide molecular evidence supporting that genetic defects in SMAD4 and increased TGFβ levels in colon cancer cells are associated with transition to malignancy with the acquisition of angiogenic and metastatic potential. These findings form a molecular basis for the creation of model systems harboring a SMAD4 defect to aid in the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets for colon cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

Isogenic HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− colon cancer cell lines [(a kind gift from Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins)] were maintained in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 0.4mg/ml G418, 0.1mg/ml hygromycin B and 10% FBS. SW620 colon cancer cell line and 293FT cell line were obtained from ATCC and were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Whenever necessary, cells were cultured in a Napco 8000WJ hypoxic incubator (Thermo) to maintain hypoxic (1% O2) conditions.

Antibodies and reagents

The following antibodies and reagents were used in this study: VEGF (BD Biosciences), Smad4 (Santa Cruz) anti-HA (Roche), β-actin and anti-Flag (Sigma), Smad2, P-Smad2, Erk, P-Erk (p42/44), Akt, P-Akt, p38MAPK, P-p38MAPK and cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling) and GLUT1 (Abcam). We also used protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz), inhibitors for MEK (PD98059) and p38 MAPK (SB203580) (Calbiochem) and 5′-fluorouracil (5′-FU) (Sigma).

Plasmid construction

To generate the pBabe-puro-TGFβRII-HA plasmid, TGFβRII-HA cDNA was excised from pCEP4-Zeo/Hyg-TGFβRII-HA plasmid (24), using BamHI/HindIII digestion followed by Klenow enzyme reaction to generate a blunt-end DNA fragment and then ligated into SnaBI-digested, pBabe-puro vector. To generate the pBabe-puro-Smad4-Flag plasmid, Smad4-Flag cDNA was excised from a PRK5-Smad4-Flag plasmid (25) using EcoRI/HindIII digestion followed by Klenow enzyme reaction and then ligated into SnaBI-digested pBabe-puro vector. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing.

Viral production and infection of target cells

Retrovirus was generated by cotransfection of pBabe-puro empty vector or pBabe-puro-Smad4-Flag or pBabe-puro-TGFβRII-HA along with pVSV-G (envelope) and pVSV-GP (packaging) plasmids in 293FT cells. Target cells were infected overnight with 4ml of virus-containing medium in the presence of 10μg/ml polybrene. The next day, cells were cultured in fresh medium and allowed to grow for another 24h. After replacing with fresh medium, cells were selected with 2μg/ml puromycin for 7–10 days, pooled and used for further assays.

Western Blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (26).

Transient transfections and luciferase reporter assays

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates (Corning) overninght prior to transfection. Transfections of firefly luciferase reporter and Renilla luciferase (internal control) plasmids were performed using Fugene (Roche). Transfected cells were allowed to grow overnight prior to TGFβ treatments. Firefly luciferase reporter activity was measured with a dual luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using a Monolight 3010 luminometer (BD Biosciences) at 570nm. Expression was calculated as the ratio of arbitrary firefly luciferase units normalized to Renilla luciferase. These experiments were independently repeated three times and each treatment consisted of triplicate samples.

Drug and inhibitor treatments

HCT116 cells were seeded in 6-well or 12-well plates 24h prior to any treatment. Cells were pre-treated 30 min before the beginning of each experiment with 20μM MEK inhibitor (PD98059), 20μM p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580) (Calbiochem) or 1μg/ml 5′fluorouracil (Sigma).

Wound healing assays

Cells were grown to confluency and a wound was introduced using a sterile Q-tip. The ability of cells to migrate was monitored at different time points using a light microscope. Images were captured using a Nikon E4300 digital camera to monitor the cell migration rate.

ELISA assays

Cells were seeded and allowed to grow for 24h. Culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium and cells were allowed to grow for another 36h. After collecting the conditioned medium, cells were washed again with 1ml of serum-free medium, pH 5.0, to enhance the release of VEGF bound to the VEGF receptors on the cell membrane. This medium was pooled with the previously harvested conditioned medium and concentrated five times by centrifugation (7500 × g for 15min) using an Amicon 50K filter unit (Millipore). Secreted VEGF was quantified using a human VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Lactate Assay

Equal numbers of HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− cells were plated and allowed to grow for 24h under normoxic conditions. The amount of lactate in the culture media secreted by the cells was measured using a lactate assay kit (Biovision), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Oxygen consumption assay

The oxygen consumption rates were measured as described in supplementary methods.

Zymogram assays

Conditioned medium from cells was collected as described above. The activity of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) was assessed by resolving the concentrated conditioned media on 10% gelatin native zymogram gels (Novex) followed by coomassie blue staining.

Protein co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed following co-transfection of PRK5-Smad4-Flag along with pCDNA3-HIF1αAA or pCDNA3-HIF2αAA vectors in HCT116 cells. Cells were cultured under 1% O2 conditions for 5h and then were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS and 5mM EDTA), containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Immunoprecipitation was performed using either anti-mouse IgG or anti-Flag antibodies in 300 μl total cell lysate using 30 μl protein A/G-agarose beads followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. The immune complexes were washed five times with 1ml lysis buffer and analyzed by Western blotting.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed paired t-test was performed for statistical analysis of luciferase assays. A p value of less than 0.05 (indicated by the * symbol in respective figures) was considered statistically significant. Error bars represent ± standard error (S.E.) values.

Results

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms that drive colon cancer progression to malignancy and metastasis, we hypothesized that loss of Smad4 function along with TGFβ overexpression and intact TGFβRII contribute to the acquisition of malignant properties of colon cancer cells. Here, we describe the use of model cell lines to dissect the molecular basis for angiogenic and metastatic phenotypic properties resulting from SMAD4 deficiency that promote colon cancer progression.

Development and characterization of colon cancer cell line model systems

To test our hypothesis, we first generated appropriate colon cancer cell line model systems. We used two independent colon cancer cell lines, HCT116 and SW620, to examine the contribution of SMAD4 defect in colon cancer.

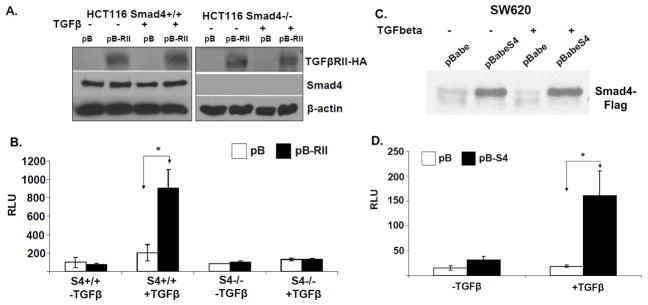

First, we took advantage of a pair of isogenic HCT116 cells that are either SMAD4 proficient (+/+) or deficient (−/−), due to somatic deletions of both SMAD4 alleles engineered by homologous recombination (24). Since these isogenic HCT116 cell lines harbor a mutation in the TGFβRII which inactivates its kinase activity (27), we stably restored the expression of wild-type TGFβRII using retroviral gene transduction. The following stable colon cancer cell lines were generated: HCT116 SMAD4+/+ pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA as well as the isogenic SMAD4−/− pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Establishment and verification of HCT116 and SW620 colon cancer model cell lines.

A. Western blotting of total cell lysates isolated from HCT116 SMAD4+/+ pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA as well as the isogenic SMAD4−/− pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA cells for detection of exogenously expressed TGFβRII-HA. B. SBE4-Luc luciferase reporter assay in the HCT116 cell lines. Cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ for 5h before lysis. C. Western blotting analysis of total cell lysates isolated from the stable SW620-pB and isogenic SW620-pBSMAD4 cells for detection of exogenously expressed Smad4-Flag. D. SBE4-Luc luciferase reporter assays in SW620 cells. Cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ for 5h before lysis.

Secondly, we stably restored the expression of wildtype Smad4 in the SW620 colon cancer cell line, with previously reported metastatic potential (28), as these cells harbor a deletion and a nonsense mutation in each of the two SMAD4 alleles. In both systems, TGFβRII and Smad4 expression were verified by Western blotting (Figure 1A & C) and the restoration of an intact TGFβ signaling pathway was confirmed by Smad-binding element luciferase (SBE4-Luc) reporter assays (Figure 1B & D). Treatment of HCT116 SMAD4+/+ pB-RII and SW620-pBSmad4 cells with TGFβ resulted in transactivation of the luciferase reporter. These steps enabled us to generate two isogenic pairs of in vitro model systems ideal to study the relationship between TGFβ signaling and/or SMAD4 status and the malignant properties of colon cancer cells.

Smad4 suppresses VEGF expression in colon cancer cells

To investigate the expression of genes involved in the biological effects of Smad4-mediate suppression of colorectal tumorigenesis, we first examined the effects of Smad4 on the expression of VEGF, a well established regulator of angiogenesis and metastasis, overexpressed in a wide variety of human tumors (29, 30).

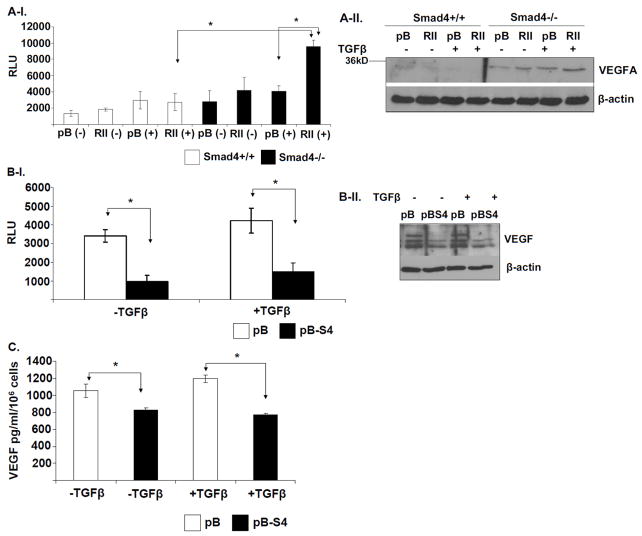

We performed VEGF-Luc reporter assays in the HCT116 cell line model system to assess the effects of Smad4 and TGFβRII status on VEGF transcription. Upon treatment with TGFβ following serum starvation, HCT116 SMAD4−/− cells with restored TGFβRII expression exhibited increased VEGF promoter activity compared to the SMAD4+/+ cells (Figure 2A-I). These results were also consistent with the VEGF protein levels (Figure 2A-II). To independently confirm these findings, we also used the SW620 system. As predicted, restoring Smad4 expression in these cells resulted in significantly reduced VEGF promoter activity (Figure 2B-I) and corresponding reduction in VEGF protein levels (Figure 2B-II).

Figure 2. Smad4 suppresses VEGF expression in colon cancer cells.

A-I. Four groups of the indicated engineered HCT116 cell lines were either mock- treated or treated with 5ng/ml TGFβ for 24h. SBE4-Luc luciferase reporter assays were performed in the Mock- or TGFβ-treated HCT116 SMAD4+/+ (WT) pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA cells, mock- or TGFβ-treated SMAD4−/− (S4-) pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA cells. A-II. Western blotting was used to detect VEGF protein levels in corresponding total cell lysates. B-I. SW620-pB and isogenic SW620-pBSMAD4 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with mock or 5ng/ml TGFβ for 24h. SBE4-Luc luciferase reporter assay was performed in the corresponding SW620 cells. Samples were measured in triplicates and the experiment was independently performed three times. II. Western blotting of total cell lysates was used to detect VEGF protein levels in the same four samples as indicated. C. Smad4 expression suppresses VEGF secretion from the SW620 cells. SW620-pB and SW620pBSmad4 cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM medium for 24h in the absence (-) or presence (+) of 5ng/ml TGFβ. Secreted VEGF was quantified by ELISA assay for VEGF in the conditioned media collected from each cell line. Results are presented as the average of triplicate measurements.

Since VEGF is a secreted growth factor which can mediate the angiogenic program of tumors in an autocrine and paracrine fashion, we hypothesized that SMAD4-deficient cells secrete more VEGF compared to SMAD4-proficient cells. ELISA assays confirmed that restoration of Smad4 expression in SW620 caused the suppression of VEGF secretion (Figure 2C). Overall, these studies demonstrated that Smad4 suppresses VEGF expression in the colon cancer cells.

Activation of auxiliary signaling pathways by TGFβ results in VEGF upregulation in SMAD4 deficient cells

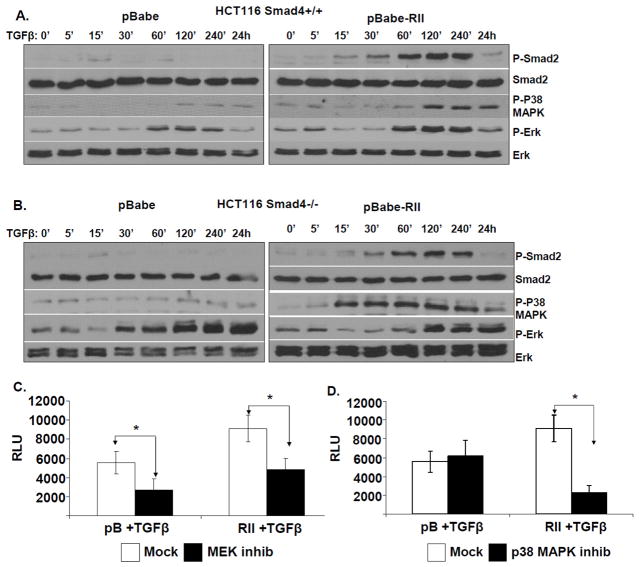

It is well known that TGFβ can potently activate Smad-dependent as well as Smad-independent signaling pathways (31). Therefore, we hypothesized that the effects of Smad4 loss on VEGF expression might be mediated through activation of auxiliary signaling pathways. To test this, we examined the effects of Smad4 and TGFβRII status on the kinetics of TGFβ-activated signaling pathways. The four groups of HCT116 cells (proficient and deficient in Smad4 and with or without TGFβRII restoration) were serum-starved overnight and then treated with TGFβ for various time points as indicated in Figure 3. The kinetics of the major downstream TGFβ-activated signaling pathways that have been shown to be involved in cancer progression was determined by Western blotting. We observed increased phosphorylated MAPK in the presence of RII indicating the likely reconstitution of auxiliary signaling pathways. Interestingly, TGFβ treatment caused prolonged activation of the MEK-Erk pathway in the SMAD4 −/− cells compared to the SMAD4 +/+ cells in a TGFβRII status independent manner (Figure 3A & B). Furthermore, the retention of wild-type TGFβRII appeared to be necessary for the TGFβ-induced activation of the p38-MAPK pathway in both SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4 −/− cells and exhibited a much earlier activation in the SMAD4-deficient cells compared to SMAD4-proficient cells in response to TGFβ (Figure 3A & B). While the MEK-Erk pathway remained consistently overactive, a similar early activation of the p38-MAPK pathway was also observed in the SMAD4-deficient SW620 cells in response to TGFβ (Supplementary Figure S1). The hyperactivity of the MEK-Erk pathway in both SMAD4-deficient and proficient SW620 cells may be derived from other genetic differences between SW620 and HCT116.

Figure 3. Involvement of MEK-Erk and p38MAPK pathways in the upregulation of VEGF in SMAD4 defective cells.

A. HCT116 SMAD4+/+ pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA as well as B. SMAD4−/− pBabe and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA cells were serum-starved overnight and then treated with 2 ng/ml TGFβ for the indicated time periods. Western blotting of total cell lysates was used to monitor the kinetics of Smad2, Erk and p38MAPK phosphorylation. C & D. HCT116 SMAD4−/− pBabe and pBabe-RII-HA cells were cultured in serum-free medium and transfected with VEGF-luc and Renilla plasmids for 16h. Cells were then treated either with mock (DMSO) or with pharmacological inhibitors against MEK kinase (PD98059-20μM) (C) or p38 MAPK (SB203580–20μM) (D) for 30 min prior to mock- or TGFβ treatment (5 ng/ml) for an additional 24h. The samples were measured in triplicates and the experiment was independently performed three times.

Both MEK-Erk and p38-MAPK pathways have been implicated in the regulation of VEGF expression in cancer cells (32, 33). Since our data suggested that these pathways become overactive in SMAD4-deficient colon cancer cells in response to TGFβ, we decided to test whether VEGF upregulation is mediated through these signaling cascades. We found that pharmacological inhibition of MEK-Erk and p38-MAPK pathways in SMAD4 −/− cells suppressed VEGF promoter activity, as indicated by VEGF-Luc reporter assays (Figure 3C & D). Consistent with our signaling pathway kinetics data, treatment with the MEK inhibitor suppressed VEGF activation in both SMAD4 −/− pB and SMAD4 −/− pBTGFβRII cells (Figure 3C), whereas p38-MAPK inhibition suppressed VEGF expression only in the SMAD4 −/− pBTGFβRII cells (Figure 3D). In conclusion, these studies suggest that SMAD4 loss in the presence of functional TGFβRII results in an increase in VEGF expression caused, at least in part, by TGFβ-induced overactivation of the MEK-Erk and p38-MAPK signaling pathways.

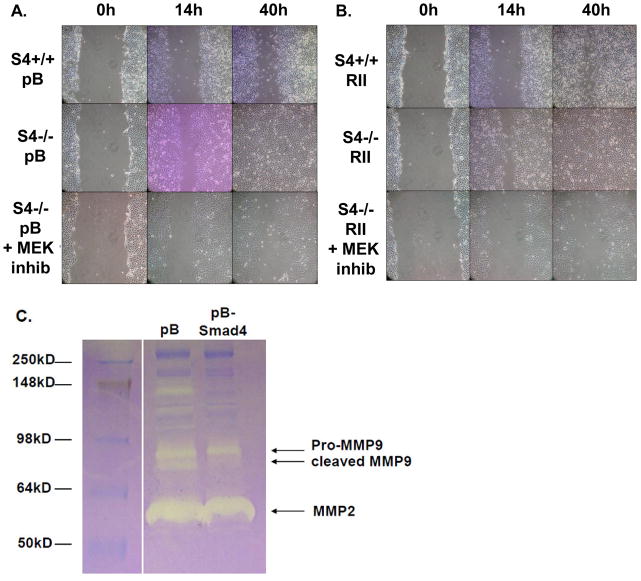

SMAD4 loss causes increases in cell motility and MMP9 activity

To evaluate the effects of Smad4 deficiency on the migratory properties of colon cancer cells, we performed wound healing assays. We found that HCT116 SMAD4−/− cells migrated into the cell-free areas and completely closed the wound in 40h, while the migration rate of HCT116 SMAD4+/+ cell was significantly reduced (Figure 4). Interestingly, the accelerated migration of SMAD4-deficient cells appeared to be independent of the status of TGFβ RII (Fig 4A & B). Since SMAD4 loss was found to enhance TGFβ-induced Erk phosphorylation (Figure 3A), we hypothesized that overactivation of this pathway might be involved in the acquisition of pro-migratory properties. Consistent with this notion, treatment of SMAD4−/− cells with MEK inhibitor suppressed the cell migration (Figure 4A & B). These data suggest that SMAD4 loss enhances the migration rate of HCT116 cells and that activation of the MEK-Erk pathway might be involved in this process.

Figure 4. Smad4 suppresses colon cancer cell migration and MMP9 activity.

HCT116 SMAD4+/+ pBabe and SMAD4−/− pBabe (A) as well as pBabe-TGFβRII-HA and pBabe-TGFβRII-HA cells (B) were grown to confluency and then a cell-free area was introduced using a sterile Q-tip. Cells were either mock-treated or treated with 20μM MEK kinase inhibitor (PD98059) 30 minutes prior to introduction of the cell scratch. The ability of the cells to migrate into the cell-free area was monitored over time. Images show representative examples of three independent experiments. C. SW620-pB and SW620-pBSMAD4 cells were cultured in serum-free medium for 36h. Conditioned medium was collected and concentrated by centrifugation. Equal protein-containing samples were analyzed by zymogram gel assays. The gelatinolytic activities of MMP2, pro-MMP9 and cleaved MMP9 were detected by coommassie blue staining as clear bands on the gel at molecular weights corresponding to 60kD, 97kD and 85kD, respectively.

The invasion of cancer cells from the primary tumor site into the blood stream, a process known as intravasation, is a critical step required for the metastatic dissemination. It could be aided by not only the acquisition of a more migratory phenotype, but also through the upregulation of matrix metalloprotease (MMP) enzymes involved in the degradation of the extracellular matrix. To test whether SMAD4 status affects the activity of such enzymes, we performed zymogram assays using conditioned media from the parental SMAD4-deficient and SMAD4-reconstituted SW620 cells. Restoration of Smad4 expression suppressed the MMP9 activity in these cells (Figure 4C) supporting the notion that Smad4 acts to inhibit both the migratory and invasive properties of colon cancer cells.

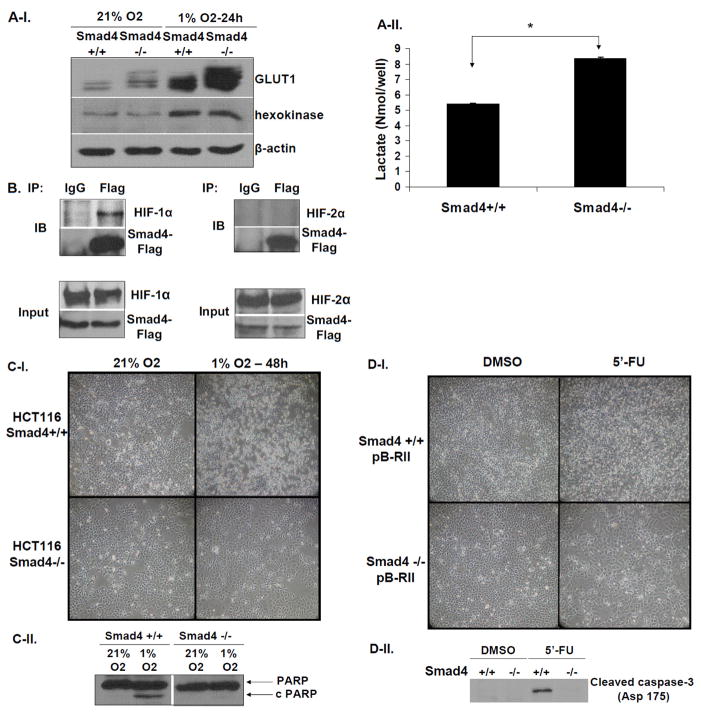

SMAD4 loss suppresses hypoxia-induced cell death, induces aerobic glycolysis and promotes 5′-fluorouracil resistance of colon cancer cells

Since increased glycolytic rates have been correlated with chemoresistance of colon cancer cells (34), we hypothesized that loss of Smad4 might affect the expression of enzymes associated with the glycolytic pathway under hypoxic conditions that mimic the microenvironment of advanced tumors. Indeed, SMAD4-deficient cells exhibited higher levels of the major glucose transporter GLUT1, but not hexokinase, when cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions, compared to SMAD4-proficient cells (Figure 5A-I). In addition, SMAD4 deficient cells secrete significantly higher levels of lactate compared to SMAD4+/+ cells (Figure 5A-II) indicating enhanced rate of aerobic glycolysis. Interestingly, we also found that Smad4 physically interacts with HIF1α, but not HIF2α, under hypoxic conditions (Figure 5B) suggesting that it may negatively regulate HIF1α-mediated GLUT1 expression. Furthermore, this phenomenon was also not associated with altered oxygen consumption rate (Supplementary Figure S2) indicating that mitochondrial function and oxidative respiration is not involved. Consistent with these findings, SMAD4-null cells were resistant to hypoxia-induced cell death compared to their wild type counterparts (Figure 5C). Overall, these observations suggested that the increase in GLUT1 protein levels, due to SMAD4 loss, may be correlated to an increased rate of aerobic glycolysis and survival under hypoxic conditions.

Figure 5. SMAD4 deficiency correlates with increased GLUT1 levels and resistance to hypoxia-induced cell death and 5′-fluorouracil treatment.

A-I. Loss of SMAD4 increases GLUT1 protein levels. Western blotting for detection of GLUT1 protein levels in protein lysates isolated from HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− grown under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions for 24h. A-II. Lactate secretion from HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− cells growing under normoxic conditions. B. Smad4 physically interacts with HIF1α but not with HIF2α under hypoxic conditions. HCT116 SMAD4+/+ cells were transiently co-transfected with PRK5-SMAD4-Flag and pCDNA3-HIF1αAA vectors or PRK5-SMAD4-Flag and pCDNA3-HIF2αAA vectors, respectively, for 16h and cultured under hypoxic conditions for an additional 5h. Total cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse IgG antibody (mock) or mouse anti-Flag antibody and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting to detect either HIF1α or HIF2α. C. Representative examples of light microscopy images (C-I) and Western blotting for detection of the cleaved PARP (C-II) in HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− grown in normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic conditions (1% O2). D. Representative examples of light microscopy images (D-I) and Western blotting for detection of the cleaved caspase-3 (Asp 175) (D-II) from total cell lysates of HCT116 SMAD4+/+ and SMAD4−/− cultures which were either treated with either mock (DMSO) or 5′-fluorouracil (5′-FU) (1μg/ml) for 72h.

Based on these observations and the literature suggesting that chromosome 18q loss results in resistance to a commonly used drug for colorectal cancer treatment, 5′-fluorouracil (5′-FU) (35), we hypothesized that SMAD4 deficiency might be responsible for this effect. Treatment of HCT116 SMAD4+/+ cells with 5′-FU for 72h resulted in profound induction of apoptosis, corroborated by the presence of cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 5D-I & II). On the contrary, there was almost undetectable level of apoptosis in SMAD4−/− cells suggesting that SMAD4 defect results in the acquisition of 5′-FU resistance in colon cancer (Figure 5D-I & II).

Discussion

TGFβ overexpression and SMAD4 mutations or deletions have been directly correlated with colon cancer metastasis. Several pathological and genetic studies suggested that chromosome 18q loss is a critical event during colorectal cancer progression and that the SMAD4 tumor suppressor is the primary target for inactivation (2, 14). Subsequent reports have established that allelic loss of chromosome 18q is directly correlated with liver metastasis of colorectal cancer and poor prognosis (36, 37). Despite the strong genetic evidence for the association between SMAD4 inactivation and advanced stage of colon cancer, the molecular basis remains elusive.

To examine if SMAD4 inactivation is a major switch that favors tumor malignancy and propensity for angiogenesis and metastasis of colon cancer, we elected to use cell line model systems to investigate both the molecular basis and cellular properties associated with SMAD4 inactivation and concurrent increase in the TGFβ levels, conditions that mimic the advanced stage colorectal tumors. Since the pairs of cell lines studied are genetically identical, except for their SMAD4 status, we reasoned that comparing the properties and gene expression patterns should help to better understand the role of SMAD4 in tumor maligancy.

Here we show that Smad4 loss enhances VEGF expression synergistically with TGFβ, whereas expression of Smad4 suppresses VEGF levels in colon cancer cells. These results are consistent with a previous report using the pancreatic cancer cell line, Hs766T, harboring homozygous deletion in both SMAD4 alleles, in which the restoration of Smad4 expression was found to suppress angiogenesis and xenograft tumor growth by inhibiting VEGF expression (38). We also found that SMAD4 deficiency prolonged TGFβ-mediated Erk-phosphorylation and activation in HCT116 cells. The fact that Erk signaling is initially activated by TGFβ and eventually turned off at 24h in SMAD4+/+ cells, suggests that a phosphatase may act to revert phosphorylation to the basal levels. Our results are also consistent with hyperactivation of Ras-mediated Erk signaling and progression into undifferentiated carcinoma upon inhibition of Smad4 in transformed keratinocytes (39).

Interestingly, our data also showed that increased TGFβ-mediated activation of MEK-Erk and p38-MAPK pathways combined with SMAD4 loss, at least in part, mediates VEGF upregulation. This is in aggreement with studies showing that Erk kinase is required for VEGF upregulation in colon carcinoma cells upon serum starvation (32) as well as that p38-MAPK activation by heregulin-beta-1 is required for VEGF induction in endothelial cells (33). Our studies also found that SMAD4 inactivation in colon cancer cells enhances their migratory and invasive properties consistent with a previous report showing that restoration of Smad4 expression reversed the invasive phenotype of pancreatic cancer cells (40).

Clinical studies have shown that patients retaining heterozygosity at the 18q locus benefit significantly better from treatment with 5′fluorouracil than patients with LOH at this site (34). Moreover, chromosome 18q loss and absence of TGFβRII mutations were found to correlate with low survival rates in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (41). These clinical data are consistent with our findings using HCT116 cells harboring SMAD4 loss and intact TGFβRII status, which cooperate to induce VEGF expression. Other studies also showed a direct correlation between low levels of Smad4 in tumors and worse outcome following surgery and treatment with 5′-fluorouracil in colon cancer patients (42).

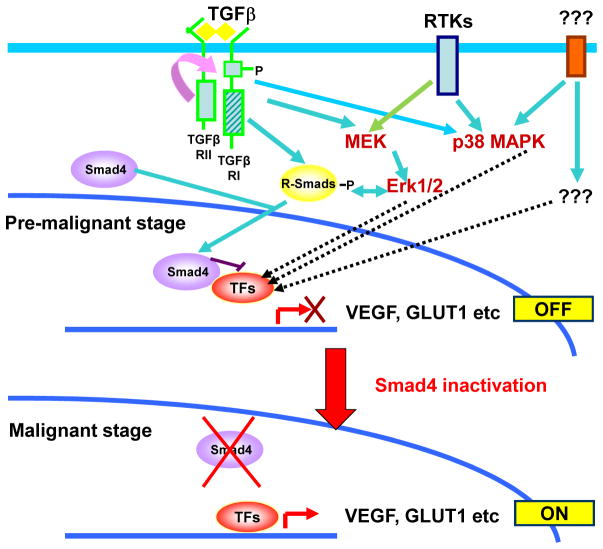

Elevated glycolytic rates, even under normoxic conditions, also known as the “Warburg effect” (43) have been correlated with the acquisition of chemoresistance in cancer cells (44, 45) and HIF1α is established as a major transcriptional regulator of the glucose transporter GLUT1 (46). Interestingly, we found that SMAD4-deficient cells exhibit increased levels of GLUT1 expression and lactate secretion as well as resistance to 5′-FU-mediated apoptosis. Since SMAD4 deficiency did not affect oxidative respiration (Figure S1), we conclude that increased glycolysis aided by the robust glucose transport contributes to the growth advantage and enhanced survival of these cells. The fact that there was physical interaction between Smad4 and HIF1α suggests a mechanistic basis for these observations. Based on these findings we propose that Smad4 may negatively regulate HIF1α-induced GLUT1 expression and the rate of aerobic glycolysis, providing a molecular link to explain the acquisition of chemoresistance in colorectal tumors harboring chromosome 18q deficiency (Figure 6).

Figure 6. SMAD4 inactivation promotes transition to malignancy in colon cancer.

Transition of pre-malignant colon cancer cells to malignancy is blocked by functional Smad4 due to inhibition of transcription factors (TFs) such as the HIF1α or other molecular events that are activated downstream of oncogenic signaling pathways and cross-talking TGFβ signaling events involved in promoting malignant properties. The inactivation of Smad4 during colon cancer progression removes the block in transition from the pre-malignant to the malignant stage by allowing accumulation of factors such as GLUT1 and VEGF.

In summary, our studies provide direct evidence for a molecular basis to explain an association between a Smad4 defect and progression to malignant colon cancer (Figure 6). The model systems described here may help to uncover novel biomarkers for advanced stage colon cancer to improve prognostic evaluations and identify effective targets for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Bert Vogelstein, Joan Massague, William Kaelin and Robert Weinberg for generously providing cell lines and reagents. These studies were supported by a grant to ST from the NIH (CA101773).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Cancer-susceptibility genes. Gatekeepers and caretakers. Nature. 1997;386:761–63. doi: 10.1038/386761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiagalingam S, Cheng K-h, Foy RL, Lee HJ, Chinnappan D, Ponte JF. TGF-beta and its Smad connection to cancer. Current Genomics. 2002;3:449–76. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun L, Wu G, Willson JK, et al. Expression of transforming growth factor beta type II receptor leads to reduced malignancy in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26449–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimchi A, Wang XF, Weinberg RA, Cheifetz S, Massague J. Absence of TGF-beta receptors and growth inhibitory responses in retinoblastoma cells. Science. 1988;240:196–99. doi: 10.1126/science.2895499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park K, Kim SJ, Bang YJ, et al. Genetic changes in the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) type II receptor gene in human gastric cancer cells: correlation with sensitivity to growth inhibition by TGF-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8772–76. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markowitz S, Wang J, Myeroff L, et al. Inactivation of the type II TGF-beta receptor in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Science. 1995;268:1336–38. doi: 10.1126/science.7761852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parsons R, Myeroff LL, Liu B, et al. Microsatellite instability and mutations of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5548–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grady WM, Myeroff LL, Swinler SE, et al. Mutational inactivation of transforming growth factor beta receptor type II in microsatellite stable colon cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:320–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim IY, Ahn HJ, Zelner DJ, et al. Genetic change in transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) receptor type I gene correlates with insensitivity to TGF-beta 1 in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science. 1996;271:350–53. 14. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thiagalingam S, Lengauer C, Leach FS, et al. Evaluation of candidate tumour suppressor genes on chromosome 18 in colorectal cancers. Nat Genet. 1996;13:343–46. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyaki M, Kuroki T. Role of Smad4 (DPC4) inactivation in human cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;306:799–804. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riggins GJ, Thiagalingam S, Rozenblum E, et al. Mad-related genes in the human. Nat Genet. 1996;13:347–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiagalingam S, Laken S, Willson JK, et al. Mechanisms underlying losses of heterozygosity in human colorectal cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051625398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyaki M, Iijima T, Konishi M, et al. Higher frequency of Smad4 gene mutation in human colorectal cancer with distant metastasis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3098–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maitra A, Molberg K, Albores-Saavedra J, Lindberg G. Loss of Dpc4 expression in colonic adenocarcinomas correlates with the presence of metastatic disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1105–11. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64625-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salovaara R, Roth S, Loukola A, et al. Frequent loss of SMAD4/DPC4 protein in colorectal cancers. Gut. 2002;51:56–59. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinacher-Schick A, Baldus SE, Romdhana B, et al. Loss of Smad4 correlates with loss of the invasion suppressor E-cadherin in advanced colorectal carcinomas. J Pathol. 2004;202:412–20. doi: 10.1002/path.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson MC, Martin JS, Cousins FM, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Akhurst RJ. Defective haematopoiesis and vasculogenesis in transforming growth factor-beta 1 knock out mice. Development. 1995;121:1845–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takaku K, Oshima M, Miyoshi H, Matsui M, Seldin MF, Taketo MM. Intestinal tumorigenesis in compound mutant mice of both Dpc4 (Smad4) and Apc genes. Cell. 1998;92:645–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S, Buckhaults P, Zawel L, et al. Targeted deletion of Smad4 shows it is required for transforming growth factor beta and activin signaling in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2412–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Feng X, We R, Derynck R. Receptor-associated Mad homologues synergize as effectors of the TGF-beta response. Nature. 1996;383:168–72. doi: 10.1038/383168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao F, Ponte JF, Papageorgis P, et al. hBub1 deficiency triggers a novel p53 mediated early apoptotic checkpoint pathway in mitotic spindle damaged cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:627–35. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.7.7928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carethers JM, Pham TT. Mutations of transforming growth factor beta 1 type II receptor, BAX, and insulin-like growth factor II receptor genes in microsatellite unstable cell lines. In Vivo. 2000;14:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhawan P, Singh AB, Deane NG, et al. Claudin-1 regulates cellular transformation and metastatic behavior in colon cancer. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1765–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI24543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren RS, Yuan H, Matli MR, Gillett NA, Ferrara N. Regulation by vascular endothelial growth factor of human colon cancer tumorigenesis in a mouse model of experimental liver metastasis. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1789–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI117857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi Y, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Ellis LM. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3964–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung YD, Nakano K, Liu W, Gallick GE, Ellis LM. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation is required for up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by serum starvation in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4804–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong S, Grijalva R, Zhang L, et al. Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer cells by the heregulin-beta1-activated p38 signaling pathway enhances endothelial cell migration. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1727–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin YK, Yoo BC, Hong YS, et al. Upregulation of glycolytic enzymes in proteins secreted from human colon cancer cells with 5-fluorouracil resistance. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:2182–92. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barratt PL, Seymour MT, Stenning SP, et al. DNA markers predicting benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil in patients with colon cancer: a molecular study. Lancet. 2002;360:1381–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:213–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka T, Watanabe T, Kazama Y, et al. Chromosome 18q deletion and Smad4 protein inactivation correlate with liver metastasis: A study matched for T-and N- classification. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1562–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarte-Waldhoff I, Volpert OV, Bouck NP, et al. Smad4/DPC4-mediated tumor suppression through suppression of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9624–29. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iglesias M, Frontelo P, Gamallo C, Quintanilla M. Blockade of Smad4 in transformed keratinocytes containing a Ras oncogene leads to hyperactivation of the Ras-dependent Erk signalling pathway associated with progression to undifferentiated carcinomas. Oncogene. 2000;19:4134–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duda DG, Sunamura M, Lefter LP, et al. Restoration of SMAD4 by gene therapy reverses the invasive phenotype in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:6857–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe T, Wu TT, Catalano PJ, et al. Molecular predictors of survival after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1196–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104193441603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alhopuro P, Alazzouzi H, Sammalkorpi H, et al. SMAD4 levels and response to 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6311–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JW, Dang CV. Cancer’s molecular sweet tooth and the Warburg effect. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8927–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertout JA, Patel SA, Simon MC. The impact of O2 availability on human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:967–75. doi: 10.1038/nrc2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu RH, Pelicano H, Zhou Y, et al. Inhibition of glycolysis in cancer cells: a novel strategy to overcome drug resistance associated with mitochondrial respiratory defect and hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:613–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A. Regulation of glut1 mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9519–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.