Abstract

Background

Despite ongoing clinical trials, the optimal time for delivery of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMCs) following myocardial infarction (MI) is unclear. We compared the viability and effects of transplanted BMCs on cardiac function in the acute and sub-acute inflammatory phases of MI.

Methods and Results

The time-course of acute inflammatory cell infiltration was quantified by FACS analysis of enzymatically digested hearts of FVB mice (n=12) following LAD ligation. Mac-1+Gr-1high neutrophil infiltration peaked at day 4. BMCs were harvested from transgenic FVB mice expressing firefly luciferase (Fluc) and green fluorescent protein (GFP). Afterwards, 2.5×106 BMCs were injected into the left ventricle of wild-type FVB mice either immediately (Acute BMC) or 7 days (Sub-acute BMC) after MI, or after a sham procedure (n=8 per group). In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) showed an early signal increase in both BMC groups at day 7, followed by a non-significant trend (P=0.203) towards improved BMC survival in the Sub-acute BMC group that persisted until the BLI signal reached background levels after 42 days. Compared to controls (MI + saline injection), echocardiography showed a significant preservation of fractional shortening at 4 weeks (Acute BMC vs saline; P<0.01) and 6 weeks (both BMC groups vs saline; P<0.05), but no significant differences between the two BMC groups. FACS analysis of BMC injected hearts at day 7 revealed that GFP+ BMCs expressed hematopoietic (CD45, Mac-1, Gr-1), minimal progenitor (Sca-1, c-kit), and no endothelial (CD133, Flk-1) or cardiac (Trop-T) cell markers.

Conclusion

Timing of BMC delivery has minimal effects on intramyocardial retention and preservation of cardiac function. In general, there is poor long-term engraftment and BMCs tend to adopt inflammatory cell phenotypes.

Keywords: Bone marrow mononuclear cells, myocardial infarction, delivery timing, bioluminescent imaging

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the principal cause of heart failure and its prevalence continues to increase1. Due to the low regenerative capacity of the human heart, myocardial infarction (MI) leads to an irreversible loss of cardiomyocytes and ventricular remodeling. In recent years, treatment with autologous bone marrow-derived stem cells has been suggested to reduce myocardial damage in patients with MI2. Although different bone marrow cell subpopulations have been proposed to aid to cardiac repair, unfractionated autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMCs) were used as donor cells in the majority of clinical trials, mainly because of the ability to safely and quickly isolate these cells. The mononuclear part of the bone marrow includes a heterogeneous mixture of cells with varying percentages of hematopoietic stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells, mesenchymal stem cells, side population cells, as well as adult myeloid and lymphoid cells3.

The potential mechanism(s) by which transplanted BMCs can improve cardiac function remains a subject of debate. Beyond these mechanical considerations, several basic technical issues remain to be clarified, such as the optimal cell type, route of delivery, and timing of cell transplantation. Following acute MI, a robust inflammatory response occurs that is necessary for healing and scar formation and contributes to cardiac remodeling4. The benefits of BMC transplantation in the acute phase after MI may thus be jeopardized by the local inflammation that renders the myocardium a hostile environment for the injected cells. On the other hand, experimental studies have demonstrated that BMC transplantation can lead to a reduction of cardiomyocyte apoptosis5, suggesting that early timing of cell delivery might be the most efficient. Clearly, the optimal time point for cell delivery after myocardial infarction remains unknown.

To date, very few studies have addressed the timing of BMC transplantation, and those studies have relied on post-mortem analysis such as real-time PCR6 and immunohistochemistry7. These methods are highly dependent on the chosen time points of animal sacrifice and provide only a limited “snapshot” representation rather than a complete picture of cell survival over time. To overcome these issues, our group has been developing and validating imaging techniques for tracking transplanted stem cells in vivo8. In this study, we investigated the viability and effects of transplanted BMCs on cardiac function in the acute and sub-acute inflammatory phases of MI using molecular imaging techniques. In addition, we analyzed the phenotype of BMCs transplanted into acute inflammatory myocardium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic L2G animals expressing Fluc-GFP

The donor group consisted of male L2G85 mice (8 weeks old), which were bred on FVB background and ubiquitously expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) and firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter genes driven by a β-actin promoter as previously described9. Recipient animals consisted of syngeneic, female FVB/NJ mice (8 weeks old, Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animal care was provided in accordance with the Stanford University School of Medicine guidelines and policies for the use of laboratory animals.

Preparation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMCs)

BMCs were harvested from the long bones of male L2G85 transgenic mice (n=12) and isolated by centrifugation in a density cell separation medium (Ficoll-Hypaque; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) prior to intramyocardial injection.

BMC proliferation assay

Proliferation was determined by the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. 5×105 BMCs were plated in 100 μl IMDM (10% FBS) into a 96-well plate in triplicates and were incubated under normoxic (95%O2/5%CO2) and hypoxic (1%O2/5%CO2/94%N2) conditions for 32 hours. 20 μl of MTT was added to each well, followed by incubation for an additional 4 hours. Absorbance was determined with a multi-well absorbance reader (Genios, Tecan Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) at 490 nm using Magellon v6.2 software.

Surgical model for acute and subacute myocardial infarction

Female FVB mice (8 weeks old) were intubated with a 20-gauge angiocath (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. Cincinnati, OH) and placed under general anesthesia with isoflurane (2%). Myocardial infarction (MI) was created by ligation of the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery with 8-0 ethilon suture through a left anterolateral thoracotomy as described10. In the acute MI model (n=8 animals), both the infarct and peri-infarct regions were injected with 25 μl containing 2.5×106 cells or saline immediately following MI using a Hamilton syringe with a 30-gauge needle. In the subacute model (n=8 anaimls), BMCs were injected after re-thoracotomy on day 7 following MI. Control group underwent sham surgery without LAD ligation followed by BMC injection (n=8 animals). To address the issue of whether cell survival is affected by injecting lower cell number, an additional group of animals (n=4) was injected at the peri-infarct region immediately following MI with 25 μl containing 1×106 cells. All surgical procedures were performed in a blinded fashion by one micro-surgeon (G.H.) with many years of experience on this model.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell and/or myocardial tissue

Freshly isolated BMCs were washed and incubated with conjugated primary antibody for 45 min at 4°C. For tissue analysis, hearts were surgically explanted, minced and digested for 2 hours in Collagenase D (2 mg/mL; Worthington Biochemical) at room temperature in RPMI 1640 media (Sigma Chemical Co.) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies). Myocardial cell suspensions were run through a 70-m cell strainer, washed in FACS buffer (PBS 2% FCS) and incubated with conjugated primary antibody for 45 min at 4°C. For Troponin T staining, a 30-min incubation in cell permeabilization buffer was performed prior to antibody incubation. Finally, cells were washed, incubated with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) cell viability solution (eBiosciences), and analyzed on a FACSCalibur system (BD Biosciences). The number of events was set at 20,000. Next, live cells were gated from dead cells and debris based on negative 7-AAD cell viability solution staining, as well as on side and forward scatter characteristics. The following antibodies were used in this study: APC-conjugated CD45 (clone: 30-F11), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5) and C-kit (2B8); Phycoerythin (PE)-conjugated Mac-1 (M1/70), Flk-1 (Avas 12α1) (BD Biosciences), Sca-1 (D7) and CD133 (13A4) (eBioscience); purified goat-anti Troponin T-C (C-19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by Alexa Fluor 647 Chicken Anti-Goat IgG (Molecular probes).

In vivo optical bioluminescence imaging (BLI)

BLI was performed using the IVIS 200 (Xenogen, Alameda, CA, USA) system. Recipient mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in the imaging chamber. After acquisition of a baseline image, mice were intraperitoneally injected with D-Luciferin (400 mg/kg body weight). Mice were imaged on days 2, 4, 7, and weekly until sacrifice at week 6. BLI signal was quantified in units of maximum photons per second per centimeter square per steridian (photons/s/cm2/sr) and presented as Log[photons/s/cm2/sr].

Echocardiography to assess left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS)

Echocardiography was performed using the General Electric Vivid 7 Dimension imaging system equipped with a 13-MHz linear probe (General Electric, Milwaukee). Animals were induced with isoflurane, received continuous inhaled anesthetic (1.5%–2%) for the duration of the imaging session, and were imaged in the supine position. Echocardiography was performed by an independent operator (J.A.G.) blinded to the study conditions. M-mode short axis views of the left ventricle were obtained and archived. Analysis of the M-mode images was performed using GE built-in analysis software. Left ventricular end diastolic diameter (EDD) and end-systolic diameter (ESD) were measured and used to calculate fractional shortening (FS) by the following formula: FS = (EDD – ESD)/EDD.

Ex vivo TaqMan PCR

In our protocol, the transplanted cells were derived from male mice and were transplanted into female recipients, which facilitate quantification of male cells in the explanted female hearts by tracking the Sry locus found on the Y chromosome. Animals were sacrificed and hearts (n=3 per group) were explanted, minced, and homogenized in 2 mL DNAzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The DNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA was quantified on a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and 500 ng DNA was processed for TaqMan PCR using primers specific for the Sry locus. RT-PCR reactions were conducted in iCylcer IQ Real-Time Detection Systems (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Detection levels were compared to a standard curve to assess the number of viable cells per sample. All samples were conducted in triplets.

Tissue collection, immunofluorescence staining, and histological analysis

Explanted hearts were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours at room temperature and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Tissue was frozen in optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT compound, Sakura Finetek) and sectioned at 5 μm on a cryostat. Serial sections were blocked and incubated with rat anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11) (BD Biosciences) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by goat anti-rat Alexa 594 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min. Sections were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Molecular Probes) and analyzed with a Leica DMRB fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems, Frankfurt, Germany). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining (Sigma) was performed according to established protocols.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were done by independent sample t-tests. BLI results were analyzed with a 3×8 repeated-measures ANOVA with group and days as fixed factors, with days as the repeated factor. A Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used for non-sphericity. Differences were considered significant for P-values <0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software for Windows (SPSS)

RESULTS

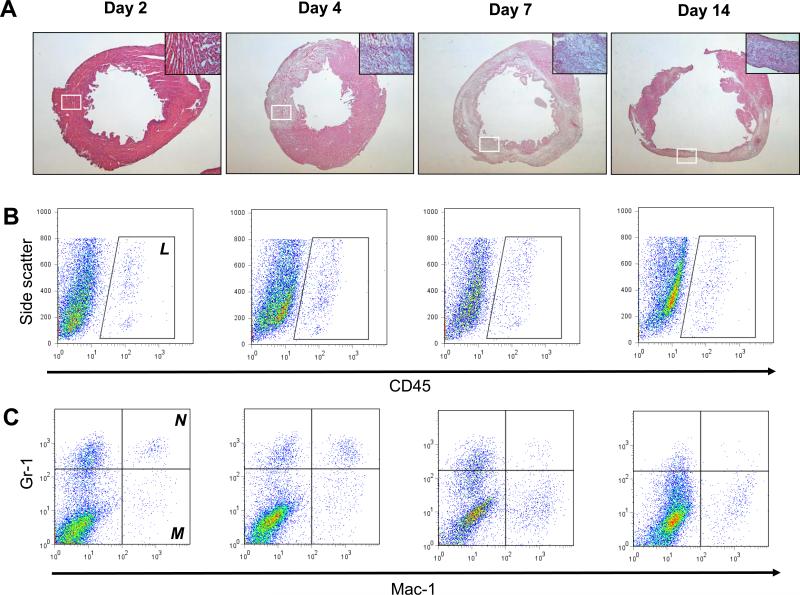

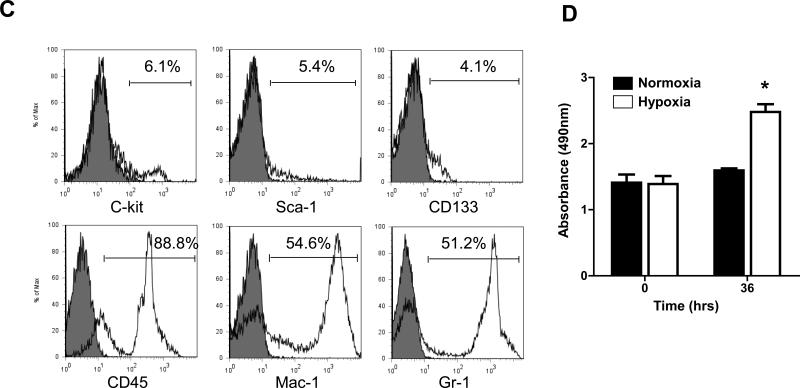

Quantification of acute myocardial inflammation following myocardial infarction in mice

Acute MI triggers an acute inflammatory phase, dominated by infiltrating neutrophils that produce reactive oxygen species and proteases that cause cardiomyocyte injury. This is followed by a proliferative phase, in which infiltrating macrophages produce cytokines and growth factors that stimulate fibroblast proliferation and neovascularization11. After inducing MI in our mice, conventional histology showed a robust and progressive infiltration of inflammatory cells into the infarcted area over time, followed by scar formation and subsequent remodeling of the left ventricle (Fig 1A). To determine the transition of the inflammatory into proliferative phase, we performed a quantitative analysis of intra-myocardial infiltrating cell subsets using flow cytometry of enzymatically digested hearts. MI was created by LAD ligation in FVB mice (n=12), which were sacrificed on days 2, 4, 7, and 14 following MI (n=3 per group). Progressive infiltration of CD45+ infiltrating leukocytes was found to peak on day 4 and day 7 following MI (Fig 1B and D). More specifically, early infiltration of Mac-1+Gr-1high neutrophils was found to peak on day 4 (Fig 1C and D), whereas Mac-1+Gr-1low macrophages infiltrated the heart most predominantly on day 7 (Fig 1C and D). These findings demonstrate that in our murine model, transition of the aforementioned phases occurs between days 4 and 7 following MI.

Figure 1. Quantification of myocardial inflammation following LAD ligation in FVB mice.

(a) H&E staining performed on sections of the left ventricle at different time-points following LAD ligation shows increasing infiltration of mononuclear cells over time leading to ventricular remodeling (Magnification: 16x). Higher magnification images (200x) taken from the area within the white boxes are shown in the upper right corner of each image. (b) Corresponding panels of flow cytometric analysis show that intramyocardial infiltration of CD45+ leukocytes reaches a maximum at 4 to 7 days following LAD ligation. (c) More specifically, infiltration of Mac-1+Gr-1high neutrophils (N) peaks on day 4, whereas Mac-1+Gr-1low macrophages (M) peak on day 7 following LAD ligation. (d) Graphical representation of infiltration of inflammatory cell subsets. (Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM))

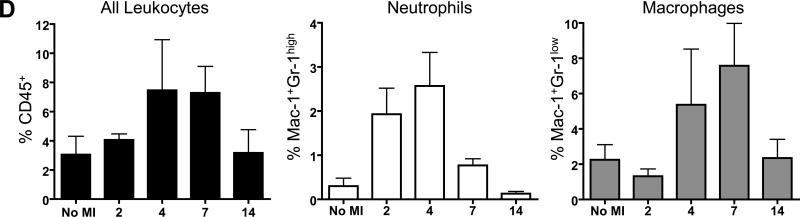

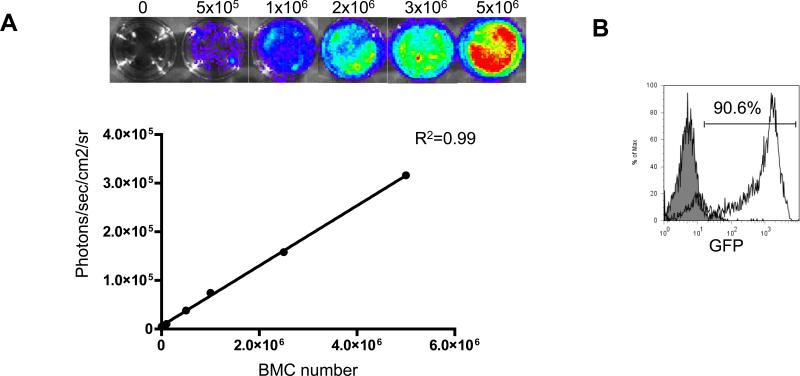

Characterization of Fluc+GFP+ BMCs

We have previously validated in vivo BLI as a reliable tool to monitor BMC engraftment into ischemic myocardium12. BLI measurements correlate highly with post-mortem methods of donor cell detection12, 13. BMC harvested from transgenic L2G85 mice (FVB background) exhibit a linear relationship between Fluc expression and BMC number (Fig 2A), as well as a strong expression of GFP (Fig 2B). FACS analysis confirmed the presence of stem/progenitor cells as well as adult hematopoietic cells within the BMC population (Fig 2C). The proliferation capacity of BMC was tested in vitro. Under hypoxic conditions, the cells showed robust proliferation when compared to BMCs kept under normoxic conditions (Fig 2D).

Figure 2. Characterization of firefly luciferase (Fluc) and green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive BMCs.

(a) Ex vivo BLI shows a linear relationship between cell number and fluc reporter gene activity. (b) There is robust expression of GFP by BMCs. (c) Further characterization of the BMC subsets shows low numbers of stem/progenitor cells (Sca-1, c-kit, CD133) and high numbers of adult hematopoietic cells (CD45, Mac-1, Gr-1). (d) Viability and proliferation capacity of transgenic BMCs were confirmed in vitro. After 36 hours under hypoxic conditions, BMCs proliferated significantly more compared to BMCs that were maintained under normoxic conditions (*P<0.01, error bars indicate SEM)

Effects of timing of BMC delivery following MI on cell viability

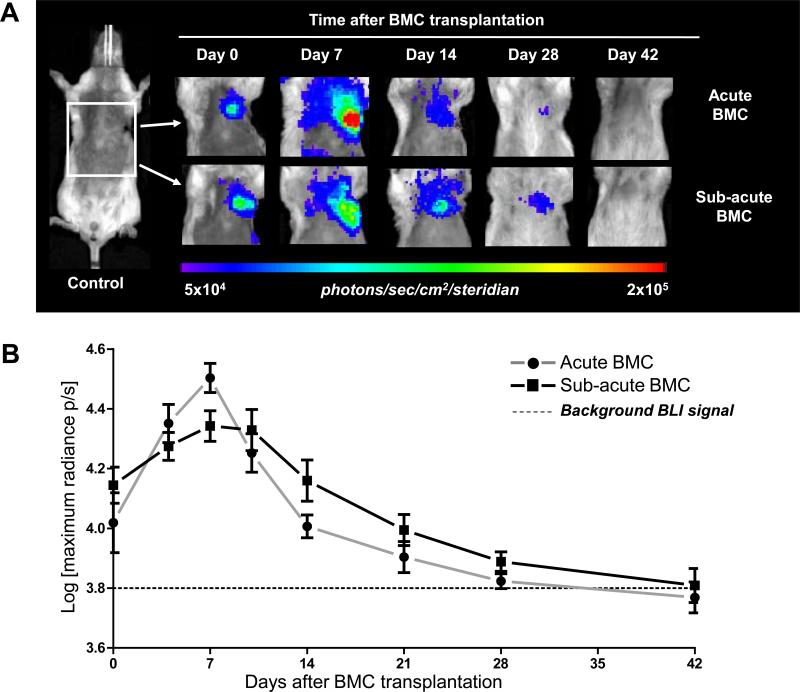

To determine whether the survival of transplanted BMCs depends on the timing of delivery, FVB mice (n=24) were randomized into the following groups: (1) LAD ligation + immediate BMC injection (Acute BMC); (2) LAD ligation + BMC injection at 7 days post-MI (Sub-acute BMC); and (3) Sham surgery + BMC injection (BMC control). In vivo BLI showed an early signal increase in both BMC groups on day 7 (Acute BMC: 4.50±0.05 vs Sub-acute BMC: 4.34±0.05 Log[photons/s/cm2/sr]), similar to validated findings in our previous study12. Although there was a highly significant effect of day (P<<.0001), there was no significant effect of group (P=0.717) nor group-by-day interaction (P=0.357). These results suggest that, independent of timing of delivery, intramyocardial retention of BMCs is limited to ~6 weeks following transplantation. In addition, we injected lower cell number (1×106, n=4) into the peri-infarct region immediately following MI. BLI data showed 2.44±0.7×104 (day 2), 5.68±1.34×104 (day 4), 5.70±0.6×104 (day 7), 4.63±0.9×104 (day 10), 6.45±2.01×104 (day 14), 4.23±0.4×104 (day 21) 2.45±0.2×104 (day 28), 1.73±0.3×104 (day 35), and 1.58±0.2×104 photons/s/cm2/sr (day 42). Overall, the cell survival followed a similar trend to that observed with transplantation of higher cell number (2.5×106). Specifically, an early signal increase followed by a progressive decline of BLI signal to background levels by ~day 42. Thus, the poor donor cell survival also does not appear to be dependent on the number of cells that were injected.

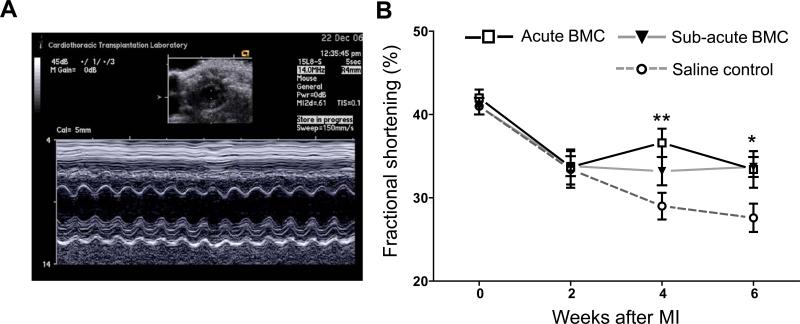

Ex vivo quantification of BMC survival

To confirm BLI findings and to rule out the possibility that BMC death might have been caused by recipient immune response towards the reporter gene, we performed LAD ligation on an additional set of female FVB mice, which were randomized to receive 2.5×106 non-labeled (wild-type) BMCs from male FVB donors (n=6) or saline (Negative control, n=3). BMC-injected animals were sacrificed at 24 hours (Positive control) and 6 weeks (n=3 per group). Their hearts were processed for quantitative TaqMan PCR analysis. Consistent with BLI data, only background levels of BMCs were detected between 6-week BMC-injected hearts and saline-injected hearts, demonstrating that no male donor BMCs could be detected intramyocardially at the 6 week time-point. In comparison, drastically higher BMC numbers were found in 24 hour relative to 6 week BMC-injected hearts (Fig 3C).

Figure 3. Longitudinal in vivo tracking of transplanted BMCs.

(a) Representative BLI images of BMC transplanted animals either acutely (Acute BMC, upper panels) or 7 days after MI (Sub-acute BMC, lower panels) show proliferation of the cells early after transplantation. Thereafter, in both groups the BLI signal decreases gradually over time to reach background levels at day 42. Color scale bar values are in photons/s/cm2/sr. (b) Graphical representation of longitudinal BLI shows increased signal intensity in both BMC groups at day 7, followed by a non-significant trend towards improved BMC survival in the Sub-acute BMC that persisted until BLI signal reached background levels at day 42 day. (c) Ex vivo quantitative TaqMan PCR detected similar levels of BMCs when comparing negative control (Neg) and 6-week BMC-injected heartsIn contrast, drastically more male BMCs were found in the 2 hour positive control (Pos) hearts (n=3 per group). (Error bars indicate SEM).

Effects of timing of BMC delivery on preservation of cardiac function

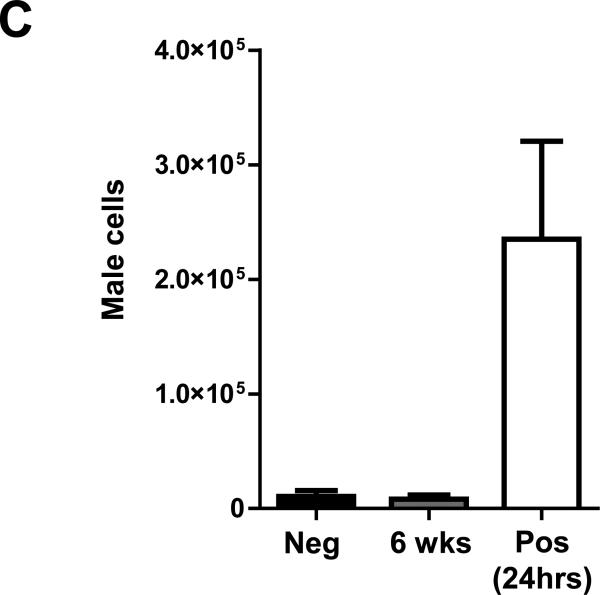

Preservation of cardiac performance was analyzed by echocardiography performed pre-operatively (base-line) and every 2 weeks following MI in the Acute and Subacute BMC animals, and compared to a control group receiving LAD ligation + saline injection (FVB, n=8). A representative M-mode tracing used for analysis is shown in Figure 4A. A significant preservation of fractional shortening was seen in BMC groups at 4 weeks (Acute BMC: 33.2±1.7% vs saline: 29.0±1.6%; P<0.01) and 6 weeks (Acute BMC: 33.7±1.2%; Sub-acute BMC: 33.4±2.2% vs saline: 27.6±1.7%; P<0.05 for both BMC groups vs. saline) following MI. However, no significant differences in cardiac contractility were found between both BMC groups during the 6-week study period (Fig 4B). Similarly, no significant difference in end-systolic and/or end-diastolic diameter were found between BMC groups at the time-points measured (data not shown).

Figure 4. Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac function.

(a) Representative M-mode echocardiogram at the level of the papillary muscle from which left ventricular diameters were measured. (b) Echocardiography revealed a significant preservation of left ventricular fractional shortening at 4 weeks in the Acute BMC group and 6 weeks in both BMC groups compared to saline control animals. No significant difference in cardiac performance was found between Acute and Sub-acute BMC animals. (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, error bars indicate SEM).

BMCs delivered into acute inflammatory environment adopt adult hematopoietic phenotypes

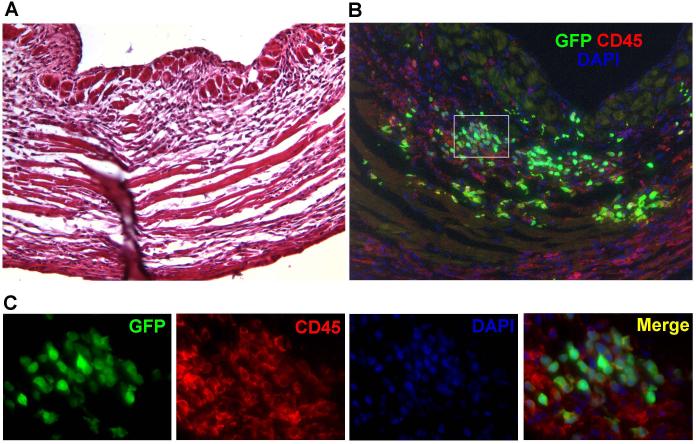

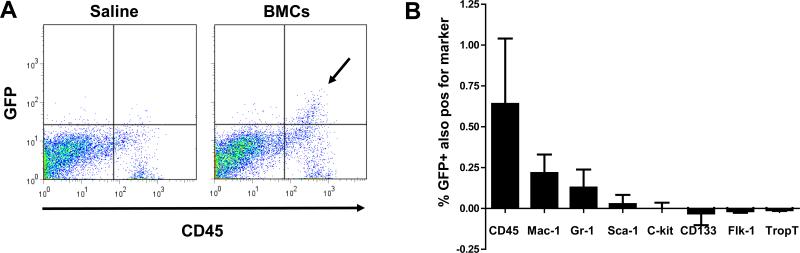

In the first week following injection, BLI imaging showed a significantly higher proliferation rate of donor BMCs that were delivered into acute inflammatory myocardium, as compared to BMCs delivered into sub-acute inflammation (Fig 3A and B). Since BMCs represent a heterogeneous cell population, we aimed to investigate the phenotype of transplanted BMC at 7 days following injection into acute myocardial inflammation. LAD ligation + acute BMC (n=4) or saline (n=3) injection was performed in an additional set of FVB mice, which were sacrificed for heart procurement at 7 days post-transplant. Conventional H&E staining of sections of the left ventricle showed robust mononuclear cell infiltration and early signs of scar formation consistent with MI (Fig 5A). Immunofluorescent staining on a corresponding section revealed the presence of intramyocardial mononuclear cells, which appeared to be mostly of GFP+ donor origin (Fig 5B). Interestingly, the majority of cells which were GFP+ also co-expressed the pan-leukocyte marker CD45 (Fig 5B and C, controls included in supplemental Fig 1). Next, we performed a systematic flow cytometric analysis on explanted hearts following enzymatic digestion (n=3 per group). Figure 6A shows representative flow cytometry panels confirming that the majority of GFP+ donor BMCs (upper two quadrants) co-expressed CD45 (upper right quadrant, arrow). Serial analysis showed that GFP+ donor BMCs expressed CD45, Mac-1 and Gr-1, and minimal numbers of Sca-1 and c-kit, and remained negative for CD133, Flk-1 and/or Troponin (Trop)-T (Fig 6B). These results suggest that at 7 days following acute delivery, some of the donor BMCs adopted an adult hematopoietic phenotype, but showed no significant differentiation into endothelial (progenitor) cell (CD133 and Flk-1) and/or cardiomyocyte (Trop-T) lineages.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical analysis of BMC transplanted hearts.

(a) H&E staining of the left ventricular wall shows mononuclear cell infiltrates and scar formation consistent with myocardial infarction. (b) Immunofluorescent staining on a corresponding section reveals an abundant presence of GFP+ BMCs (green) within the infarcted myocardium, which is rich in CD45+ inflammatory cells (red). The majority of the GFP+ cells coexpressed CD45, confirming an inflammatory phenotype. Counterstaining was performed with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). (c) High power views of the selected area (Fig 2B white square) reveal that the vast majority of donor BMCs express CD45 and retain round shapes with large nuclei, representing an inflammatory phenotype.

Figure 6. Ex vivo phenotyping of donor BMCs confirms inflammatory phenotype.

(a) Representative flow cytometry panels of saline (left) and BMC (right) injected hearts at 7 days after acute BMC delivery. At this time-point GFP+ BMCs (arrow) co-express CD45, confirming their inflammatory phenotype. (b) Serial flow cytometric analysis reveals that BMCs that were GFP+ (upper half of plot) predominantly express inflammatory cell markers (CD45, Mac-1, Gr-1), rather then stem cell (Sca-1, c-kit), endothelial progenitor cell (CD133, Flk-1) or cardiomyocyte (TropT) markers. Data are presented as percentage of GFP+ cells also positive for the markerreduced by background staining. (Error bars indicate SEM).

DISCUSSION

Despite ongoing clinical trials, the optimal time-point of BMC delivery following acute MI remains a point of debate. A review of current literature reveals few studies that have systematically addressed the issue of timing of BMC transplantation14. This study was designed to determine the effects of timing of BMC delivery following acute MI in a standardized mouse LAD ligation model. Specifically, we have demonstrated that: (1) BMC transplantation in either acute or sub-acute myocardial infarction has a mildly positive effect on cardiac preservation, confirming earlier findings in animals models15 and clinical trials2; (2) retention of BMC engraftment and preservation of cardiac function are not critically dependent on the timing of delivery; and (3) injection of BMCs into the inflammatory environment of myocardial infarction leads to early proliferation of donor cells, some of which adopt adult hematopoietic phenotypes.

Earlier studies from our laboratory using in vivo BLI of transplanted BMCs revealed that the cells can effectively home in on and engraft into infarcted myocardium12, 13. Although the present study confirms the therapeutic effect of BMC transplantation in the setting of acute MI, it also clearly shows that delivery of the cells in the time-window following the hostile acute inflammatory phase (7 days after MI) does not result in extended long-term survival of donor BMCs. In addition, no significant differences were found in the preservation of cardiac function between BMCs injected groups during a 6-week period of observation.

To our knowledge, timing of BMC delivery has thus far not been investigated in experimental models. However, other cell populations, such as BM-derived mesenchymal stem cells7 and fetal cardiomyocytes16, showed therapeutic improvements in rat models when delivered in a the time-window of 1 to 2 weeks following MI. Most likely, the different observations made in our study are the results of the different cell populations used for transplantation. To represent the present clinical situation, we specifically used unfractionated BMCs. In addition to the survival data, we show that some of the BMCs that engraft intramyocardially seem to be of adult hematopoietic cell phenotype, rather than bone marrow-derived endothelial, endothelial progenitor, or cardiac cells, at least following acute delivery at the time-point tested. These findings strengthen the hypothesis that preservation of cardiac performance by BMC transplantation might be attributable to modulation of the natural process of myocardial inflammation and infarct healing17. These experiments, however, only provide insight into the phenotype of the transplanted GFP+ donor BMCs, not at the endogenous BMC recruitment process, paracrine action of these cells, or their potential capability to activate resident progenitor cells that may aid in the cardiac repair process.

Investigations aimed to reveal the mechanism(s) by which stem cells might preserve cardiac function have been plenty. Early reports pointed toward the myocardial regeneration by repopulation of BM-derived endothelial cells and/or cardiomyocytes18; however, subsequent studies failed to support those observations19. Other proposed mechanisms include donor-host cell fusion and neovascularization by either vasculogenesis and/or secretion of paracrine factors leading to angiogenesis and arteriogenesis20. Recently, studies have focused on additional mechanisms of action of transplanted BMCs, which could be by a direct paracrine effect on the inflammatory cascade. Burchfield et al. recently reported evidence that BMCs mediate cardiac protection by release of the immunomodulatory cytokine IL-10, leading to decreased intramyocardial accumulation of T-lymphocytes, which translated into reduced LV remodeling21. Similarly, Ciulla et al. found transplanted BMCs to reduce serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are known to contribute to myocardial apoptosis, necrosis, and scar formation22. These findings, combined with the results presented in the present study, suggest that BM progenitors could ameliorate LV remodeling following MI by continuing to differentiate along the hematopoietic lineage.

The clinical relevance of this study is significant. A recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of BMC transplantation in patients suffering from acute MI found no significant difference in global LV function when the cells were delivered in either less than 5 days or 5 to 30 days window period2. The present study provides similar conclusions to the the majority of clinical studies analyzed by Abdel-Latif et al2. Specifically, long-term survival and modest therapeutic efficacy of BMCs seem to be relatively independent of timing of cell delivery. Clinically significant improvements of cardiac function in patients suffering from acute MI may be achieved by repeated cellular transplants, both in the acute and sub-acute phases of myocardial inflammation. Further studies will be needed to test this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jarrett Rosenberg (Department of Radiology, Stanford University School of Medicine) for his assistance with statistical analysis.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported in part by NIH HL089027, HL099117, and Burroughs Wellcome Foundation Career Award in Biomedical Sciences (to J.C.W), Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Fellowship (JP), and by the ESOT-Astellas Study and Research Grant (RJS)

Footnotes

In the majority of clinical trials investigating cardiac stem cell-based therapy, autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMCs) have been the most common chosen cell type. However, a clinical controversy exists regarding the optimal time point to transplant BMCs following myocardial infarction (MI). In the acute phase following MI, a robust inflammatory response occurs which may jeopardize the viability of transplanted cells compared to the subacute phase. Yet the majority of cardiomyocyte apoptosis actually occurs in the earlier stages following MI. Experimental studies have demonstrated that BMC transplantation can lead to a reduction of cardiomyocyte apoptosis, which points to the importance of determining the exact timing of optimal cell delivery. In this study, we address this critical issue by using molecular imaging technology to investigate the viability of transplanted BMCs in both acute and sub-acute MI settings and to determine their subsequent effects on cardiac recovery.

Journal Subject codes: [4] Acute Myocardial Infarction, [31] Echocardiography, [33] Other diagnostic testing

DISCLOSURES: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern SM, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wilson M, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Latif A, Bolli R, Tleyjeh IM, Montori VM, Perin EC, Hornung CA, Zuba-Surma EK, Al-Mallah M, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow-derived cells for cardiac repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:989–997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimmeler S, Burchfield J, Zeiher AM. Cell-based therapy of myocardial infarction. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2008;28:208–216. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.155317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nian M, Lee P, Khaper N, Liu P. Inflammatory cytokines and postmyocardial infarction remodeling. Circulation research. 2004;94:1543–1553. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000130526.20854.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circulation Research. 2006;98:1414–1421. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225952.61196.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller-Ehmsen J, Krausgrill B, Burst V, Schenk K, Neisen UC, Fries JW, Fleischmann BK, Hescheler J, Schwinger RH. Effective engraftment but poor mid-term persistence of mononuclear and mesenchymal bone marrow cells in acute and chronic rat myocardial infarction. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2006;41:876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu X, Wang J, Chen J, Luo R, He A, Xie X, Li J. Optimal temporal delivery of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in rats with myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang SJ, Wu JC. Comparison of imaging techniques for tracking cardiac stem cell therapy. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1916–1919. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao YA, Wagers AJ, Beilhack A, Dusich J, Bachmann MH, Negrin RS, Weissman IL, Contag CH. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:221–226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swijnenburg RJ, Tanaka M, Vogel H, Baker J, Kofidis T, Gunawan F, Lebl DR, Caffarelli AD, de Bruin JL, Fedoseyeva EV, Robbins RC. Embryonic stem cell immunogenicity increases upon differentiation after transplantation into ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 2005;112:I166–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular Research. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Bogt KE, Sheikh AY, Schrepfer S, Hoyt G, Cao F, Ransohoff KJ, Swijnenburg RJ, Pearl J, Lee A, Fischbein M, Contag CH, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Comparison of different adult stem cell types for treatment of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2008;118:S121–129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheikh AY, Lin SA, Cao F, Cao Y, van der Bogt KE, Chu P, Chang CP, Contag CH, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Molecular imaging of bone marrow mononuclear cell homing and engraftment in ischemic myocardium. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2007;25:2677–2684. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartunek J, Wijns W, Heyndrickx GR, Vanderheyden M. Timing of intracoronary bone-marrow-derived stem cell transplantation after ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Nature Clinical Practice. 2006;3(Suppl 1):S52–56. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamihata H, Matsubara H, Nishiue T, Fujiyama S, Tsutsumi Y, Ozono R, Masaki H, Mori Y, Iba O, Tateishi E, Kosaki A, Shintani S, Murohara T, Imaizumi T, Iwasaka T. Implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells into ischemic myocardium enhances collateral perfusion and regional function via side supply of angioblasts, angiogenic ligands, and cytokines. Circulation. 2001;104:1046–1052. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.093817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li RK, Mickle DA, Weisel RD, Rao V, Jia ZQ. Optimal time for cardiomyocyte transplantation to maximize myocardial function after left ventricular injury. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2001;72:1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathur A, Martin JF. Stem cells and repair of the heart. Lancet. 2004;364:183–192. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC. Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature. 2004;428:668–673. doi: 10.1038/nature02460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beeres SL, Atsma DE, van Ramshorst J, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. Cell therapy for ischaemic heart disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2008;94:1214–1226. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.149476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burchfield JS, Iwasaki M, Koyanagi M, Urbich C, Rosenthal N, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Interleukin-10 from transplanted bone marrow mononuclear cells contributes to cardiac protection after myocardial infarction. Circulation Research. 2008;103:203–211. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciulla MM, Montelatici E, Ferrero S, Braidotti P, Paliotti R, Annoni G, De Camilli E, Busca G, Chiappa L, Rebulla P, Magrini F, Lazzari L. Potential advantages of cell administration on the inflammatory response compared to standard ACE inhibitor treatment in experimental myocardial infarction. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2008;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.