Abstract

It has recently been argued that shared environmental influences are moderate, identifiable, and persistent sources of individual differences in most forms of child and adolescent psychopathology, including antisocial behavior. Unfortunately, prior studies examining the stability of shared environmental influences over time were limited by possible passive gene-environment correlations, shared informants effects, and/or common experiences of trauma. The current study sought to address each of these limitations. We examined adolescent self-reported antisocial behavior in a 3.5 year longitudinal sample of 610 biological and adoptive sibling pairs from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS). Results revealed that 74–81% of shared environmental influences present at time 1 were also present at time 2, whereas most non-shared environmental influences (88–89%) were specific to a particular assessment period. Such results provide an important constructive replication of prior research, strongly suggesting that shared environmental contributions to antisocial behavior are systematic in nature.

Keywords: antisocial behavior, shared environment, stability, non-shared environment

Behavioral genetic research has historically concluded that the more important environmental influences on psychological and behavioral outcomes result in differences between siblings (referred to as non-shared or child-specific environmental influences) (Plomin & Daniels, 1987). By contrast, environmental influences that create similarities between siblings (referred to as shared or family-wide environmental influences) appear to make little to no meaningful contribution to these same outcomes (i.e., they are indistinguishable from zero). This argument has been based primarily on findings from twin and adoption studies, which have converged in suggesting that estimates of non-shared environmental influences are moderate to large across virtually all psychological and behavioral outcomes examined to date, including personality, cognitive abilities, and several forms of psychopathology.

Given the sheer magnitude and consistency of these non-shared environmental effects, it is thus rather surprising that efforts to identify them have largely failed, even when using very large samples and methodologies specifically designed to identify non-shared environmental sources of variance (Neiderhiser, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2007; Plomin, Asbury, & Dunn, 2001). Indeed, specific non-shared environmental factors typically account for no more than 2% of the variance in the outcome (Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000). Recent theorists have accordingly suggested that, rather than being a function of important and identifiable environmental influences that serve to differentiate siblings, the non-shared environment is largely comprised of idiosyncratic and/or transient environmental influences with negligible long-term explanatory power (Rutter, Silberg, O’Connor, & Simonoff, 1999; Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000). Consistent with this more recent conceptualization, longitudinal data suggest that non-shared environmental influences rarely persist over time, but instead appear to be largely specific to a given assessment period (Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Krueger, 2006; Rutter et al., 1999; Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000). In sum, there is now growing evidence that non-shared environmental influences may be less important than was originally proposed.

By contrast, more recent work has suggested that shared environmental influences are more important than was initially suggested. Burt (2009b) outlined several reasons for researchers to reconsider the relevance of the shared environment. First, the conclusion that shared environmental influences are indistinguishable from zero was almost exclusively based on studies of adults. Recent studies of child and adolescent antisocial behavior, regardless of assessment technique, have consistently revealed moderate and statistically significant effects of shared environmental influences (Buchanan, McGue, Keyes, & Iacono, in press; Burt, 2009b).

Second, shared environmental influences in childhood and adolescence appear to be identifiable (Rutter et al., 1999). For example, several independent studies using different samples and methodological designs have now suggested that the association between parental divorce and adolescent behavior problems is largely shared environmental in origin (Burt, Barnes, McGue, & Iacono, 2008; D’Onofrio et al., 2007; D’Onofrio et al., 2005; O’Connor, Caspi, DeFries, & Plomin, 2000), as is the association between the parent-child relationship and adolescent externalizing, at least in part (Burt, Krueger, McGue, & Iacono, 2003; Burt, McGue, Krueger, & Iacono, 2007; McGue, Sharma, & Benson, 1996; Pike, McGuire, Hetherington, Reiss, & Plomin, 1996). Moreover, these measured environmental factors typically account for moderate proportions (e.g., 25%) of the shared environmental variance. Shared environmental influences thus appear to be identifiable sources of environmental variance, particularly relative to non-shared environmental influences.

Finally, extant research also suggests that shared environmental influences may persist over time (at least during childhood and adolescence), further implying that these environmental influences make consequential contributions to externalizing prior to adulthood. For example, in one of the largest longitudinal twin studies to date (i.e., data at four waves was available for over 1,000 twin pairs), Bartels and colleagues (2004) examined etiological stability and change in internalizing and externalizing spectrum problems across ages 3, 7, 10, and 12. At each age, shared and non-shared environmental proportions of variance were significant and ranged between 15 and 35% (Bartels et al., 2004). Critically, however, non-shared environmental influences were largely (and, in some cases, exclusively) age-specific, accounting for only 6–10% of the stability in these behaviors. By contrast, shared environmental influences accounted for 37–43% of the stability in internalizing and externalizing problems. Shared environmental influences thus appear to be relatively stable sources of environmental variance as well, particularly when compared to non-shared environmental influences.

Such findings are collectively consistent with the notion that, although they may dissipate by adulthood, the shared environment is a moderate, persistent, and identifiable source of individual differences in externalizing behaviors prior to adulthood. However, more research is needed to confirm this conclusion, and particularly the persistence or stability of the shared environment over time, as shared environmental influences are confounded with passive gene-environment correlations (i.e., passive rGE) in traditional twin studies. Passive rGE reflect the fact that the environment provided to one’s biological children reflects the genetically influenced preferences and tendencies of the parent. Because parents share genes with their biological children, the child’s genes are then correlated with his environmental experiences. As an example, if conflictual parent-child relationships are in part a function of the parent’s tendency to be antisocial, and if antisocial behavior has a genetic component, then biological parents and children could share both the genes for the antisocial behavior and the corresponding tendency to be conflictual in their relationships. Accordingly, in biological families (such as those used in child-based twin designs), passive rGE can mimic shared environmental influences (Neiderhiser et al., 2004), when the origins are in fact a function of common parent-child genes. Fortunately, the role of passive rGE in shared environmental effects can be easily evaluated by comparing adoptive and biological siblings. Because adoptive siblings do not share genes with their adoptive family members, passive rGE are entirely eliminated, providing a “direct” estimate of shared environmental influences.

To date, however, we know of only two longitudinal adoption studies (Huizink, van den Berg, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2007; van der Valk, Verhulst, Neale, & Boomsma, 1998) examining the origins of the stability of externalizing behaviors. Both studies examined participants from a sample of internationally-adopted Dutch adolescents (aged 10–15 years at intake; N = 221 unrelated sibling pairs and 111 biologically related sibling pairs that had been adopted into the same home). Approximately 75% of the participants were assessed again roughly three years later. Externalizing behaviors at both assessments were assessed using the parent-report Child Behavior Checklist. Van der Valk et al. (1998) found that shared environmental influences present at time 1 remained relatively stable over time, accounting for 35%–47% of the shared environmental variance present at time 2. Comparable results were not explicitly presented for non-shared environmental influences, although the proportions of covariance accounted for the non-shared environment were not statistically significant (whereas those for shared environmental influences were significant at p<.05). Huizink et al. (2007) conducted similar analyses, additionally examining a time 3 assessment (conducted roughly 13 years after the initial assessment). They found that shared environmental influences were significant and could be modeled as a common factor across all three assessments, results that clearly highlight the stability of these effects over time. Non-shared environmental influences, by contrast, again appeared to be assessment-specific.

The results of the Huizink et al. (2007) and van der Valk et al. (1998) studies thus offer additional support for the contention that shared environmental influences persist over time whereas non-shared environmental influences are rather transient. Even so, there are two key aspects of these studies that limit our ability to make any firm conclusions. First, the sample in question consisted of international adoptees who were placed in their adoptive homes rather late in life (average age at placement was 2.89 years for non-biologically related siblings and 4.95 years for biologically related siblings) and who had typically experienced changes in caretaking, physical abuse, and/or physical neglect prior to placement (although likely with differing levels of severity and chronicity). Accordingly, the stable shared environmental influences observed in these data could also reflect the consequences of these common trauma experiences across siblings. Second, parental reports of externalizing were examined at assessments 1 and 2. This is important because analysis of parental-reports involves correlating a given parent’s report of each of the two children. Given this, “shared informant variance” could underlie the finding of shared environmental stability. It would thus be important to constructively replicate findings of shared environmental stability using adolescent self-reports, the latter of which necessarily involve correlating the reports of two separate informants (i.e., correlating sibling A’s self-report with sibling B’s self-report).

The current study sought to fill these gaps in the literature, so as to more definitely support or refute claims of persistent shared environmental influences on adolescent antisocial behavior over time. We examined a longitudinal sample of just over 600 biological and adoptive sibling pairs, the latter of whom were placed in their adoptive homes shortly after birth (the average age of placement was younger than five months). In this way, we sought to rule out common experiences of trauma in late-adopted youth as an explanation for any shared environmental influences we might observe. We also focused specifically on adolescent self-reports of their delinquent behaviors, an approach that has not yet been used in any existing longitudinal adoption studies (to our knowledge). As noted above, the use of self-reports is critical for the identification of shared environmental influences, as it necessarily circumvents the issue of “shared informant variance”. Finally, we conducted a series of analyses that allowed us to specifically evaluate the etiological stability of antisocial behavior over time, and in this way, more definitively examine the persistence (or lack thereof) of shared and non-shared environmental influences.

METHODS

Participants in the current study participated in the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (i.e., SIBS), a longitudinal population-based study of adoptive and biological adolescent siblings and their parents. Adoptive families living in the Minneapolis/St. Paul greater metropolitan area were contacted based on records for the three largest adoption agencies in Minnesota (averaging between 600 and 700 placements a year), and were selected to have 1) an adopted adolescent placed as an infant and first assessed between the ages of 11 and 19 years, and 2) a second non-biologically related adolescent sibling falling within the same approximate age range. Adopted adolescents had a mean age of placement of 4.8 months (SD = 4.7 months). Although biological siblings were selected to have gender and age composition similar to that of the adopted siblings, biological and adoptive families were otherwise not matched so as to obtain representative samples of both family-types (Stoolmiller, 1998). Other eligibility requirements for all families included living within driving distance of our Minneapolis-based laboratory, participating siblings no more than 5 years apart in age, and the absence of cognitive or physical handicaps (as indicated by parental report) that would preclude completion of our daylong assessment.

Among eligible families, 63% of adoptive and 57% of biological families participated. There were no significant differences between participating and non-participating adoptive families in parental education, occupational status, and marital dissolution (McGue et al., 2007). There were also no significant differences between participating and non-participating biological parents in terms of paternal education, paternal and maternal occupational status, or rate of divorce, although participating mothers were significantly more likely to have a college degree (44%) than non-participating mothers (29%). Among participating families, adoptive parents were less likely than non-adoptive parents to be diagnosed with lifetime Drug Abuse or Dependence, but there were no significant differences in the rates of major depressive disorder, nicotine dependence, antisocial personality disorder, or alcohol dependence (see McGue et al., 2007). However, as compared to non-adoptive parents, adoptive parents typically had a higher occupational status and were more likely to have a college education (44% versus 64%, respectively).

The sample examined here consisted of 406 adoptive and 204 biological families. Of the adoptive families, some (n=124) also contained a non-adopted child, who was biologically related to his or her parents, but not to the target adoptee. Roughly 38% of the sample consisted of opposite-sex sibling pairs. A little over half of the sample was female (55%). The adoptive and biological parents (and therefore, the biological adolescents) were broadly representative of the ethnic composition of the Minnesota population at the time they were born; approximately 95% were Caucasian. However, due to predominantly international adoptions in Minnesota, the adopted adolescents were 67% Asian-American, 21% Caucasian, 2% African-American, 2% East Indian, 3% Hispanic/Latino, 4% mixed race, and 1.1% other ethnicities. Participants were invited to participate in a follow-up visit an average of 3 to 4 years following their intake assessment. Our sample retention at follow-up was excellent, with a participation rate of 94%. At intake, participants ranged in age from 10 to 18 years (average 14). At follow-up, participants ranged in age from 14 to 22 years (average 18).

MEASURES

DSM-IV Symptom Count

We assessed the two symptom dimensions (i.e., criterion A and C) that comprise DSM-IV Antisocial Personality Disorder. We specifically examined the sum of endorsed or partially-endorsed criterion C symptoms at time 1 (i.e., symptoms of Conduct Disorder or CD; available on 1,189 participants) and the sum of endorsed or partially-endorsed criterion A symptoms at time 2 (i.e., the adult-specific antisocial behavior (AAB) symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder; available on 935 participants, as those participants younger than 16 at time 2 were not administered the AAB interview). All participants were assessed in-person by trained bachelor and masters-level (from psychology and related disciplines) interviewers for DSM-IV mental disorders. Siblings were interviewed by separate interviewers. CD was assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-Revised (DICA-R) (Reich, 2000; Welner, Reich, Herjanic, Jung, & Amado, 1987). Of the 13 possible symptoms of CD, only symptom 9 (“has forced someone into sexual activity with him or her”) was not assessed. AAB was assessed (as part of the Antisocial Personality Disorder interview) via the Structured Clinical Interview for personality disorders (SCID-II) (Spitzer, Williams, Gibbon, & First, 1987). Supplementary probes and questions (e.g., age of onset, frequency of behavior) were added to both interviews to ensure complete coverage of each symptom. The reporting period for CD was infancy until age 15 (the age cut-off specified in the DSM-IV), while the reporting period for AAB was since age 15. The reporting periods thus did not overlap across intake and follow-up in these data.

Our focus on CD at intake but AAB at follow-up allowed us to accommodate (at least some of) the developmental change in antisocial behavior from early- and mid-adolescence through late-adolescence/emerging adulthood, while maintaining a focus on clinically-meaningful levels of these behaviors. In particular, the behavioral manifestation of antisocial behavior changes rather dramatically from childhood to adulthood. As children, antisocial youth are likely to lie, steal, destroy property, set fires, and to be physically cruel. By early adolescence, these same youth are also likely to be truant from school, break curfew, and run away from home, behaviors that are quite rare prior to adolescence (Loeber & Hay, 1997; Renk, 2008). While some of these behaviors continue to characterize antisocial individuals in adulthood (e.g., stealing, lying, and physical cruelty), others are either no longer applicable (e.g., truancy, breaking curfew) or are expressed less frequently (e.g., fire setting). The DSM-IV captured (some of) this developmental change in its diagnostic criteria for Antisocial Personality Disorder (i.e., CD is assessed until age 15, while AAB is assessed since age 15).

Following the interview, a clinical case conference was held in which the evidence for every symptom was discussed by at least two advanced (second year and beyond) clinical psychology doctoral students. As necessary, audio tapes from the interview were replayed or the participant was re-contacted for clarification. As actual diagnoses were not used in the current study, duration rules were excluded. Symptoms judged to be definitely present (i.e., they were clinically significant in both severity and frequency) were counted as one full symptom. Symptoms judged to be probably present (i.e., they were clinically significant in either severity or frequency, but not both) were counted as half of a symptom. The reliability of the consensus process was good, with kappas of 0.79 for diagnoses of CD and .82 for “diagnoses” of AAB.

Symptom counts, rather than diagnoses, were used primarily to increase statistical power, as diagnostic prevalence rates in community-based sample are lower than in clinically-referred samples. Also, available data indicate that patterns of genetic and environmental influence are similar for categorical and dimensional models of psychopathology (Eaves et al., 1997; O’Conner, McGuire, Reiss, Hetherington, & Plomin, 1998; Sherman, McGue, & Iacono, 1997; Silberg et al., 1996; Slutske et al., 1997).

Delinquency Questionnaire

We also administered 21 items from the Delinquent Behavior Index (DBI) (Burt & Donnellan, 2008; Burt et al., 2007; Farrington & West, 1971; Gibson, 1967). Items assessed minor (e.g., skipping school) and more serious (e.g., using a weapon in a fight) delinquent behaviors. Participants were asked whether they had engaged in each behavior “as an adolescent” (0=no; 1=yes), after which items were summed. Higher scores thus reflect endorsement of more delinquent behaviors. If fewer than two items were missing, items were prorated and added to the scale score. The scale demonstrated good internal consistency reliability, with alphas of .87 and .89 at intake and follow-up, respectively. Those participants aged 19+ years at follow-up completed a reduced assessment that did not include the DBI. The DBI was thus available on 1,181 adolescents at time 1, but only 752 participants at time 2.

ANALYSES

Structural equation modeling of these data is based on the difference in the proportion of genes shared between full biological siblings (i.e., BIO), who share 50% of their segregating genetic material plus their family/common environment, and adoptive siblings (i.e., ADOP), who share only their family/common environment. Making use of these differences, BIO and ADOP sibling correlations are compared to estimate the relative contributions of additive genetic effects (A), shared environmental effects (C), and non-shared environmental effects plus measurement error (E) to the variance within observed behaviors or characteristics (i.e., phenotypes). Larger BIO than ADOP correlations are indicative of genetic mediation. Shared environmental influences are implied by equivalent BIO and ADOP correlations, and by ADOP correlations significantly greater than zero. Indeed, because they do not share segregating genetic material, significant associations between ADOP siblings function as a “direct” estimate of shared environmental influences.

We made use of a standard bivariate decomposition model, in which the variance within and the covariance between antisocial behavior at each assessment were decomposed into their genetic and environmental components. We also computed genetic and environmental correlations, which specify the proportion of genetic and environmental influences that persist over time. A shared environmental correlation of 1.0 would indicate that all shared environmental influences persist across assessments, whereas a correlation of zero would indicate no shared environmental overlap. This model thus enabled us to explicitly estimate the extent to which shared and non-shared environmental influences contribute to the stability of antisocial behavior over time.

Because of missing data, we made use of Full-Information Maximum-Likelihood raw data techniques (FIML), which produce less biased and more efficient and consistent estimates than techniques like pairwise or listwise deletion in the face of missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987). To adjust for positive skew in the data (skewness ranged from 1.6–3.3), the measures were log-transformed prior to model-fitting (skew following transformation ranged from 0.1–1.6). Mx (Neale, Boker, Xie, & Maes, 2003) was used to fit models to the transformed raw data. When fitting models to raw data, variances, covariances, and means of those data are freely estimated by minimizing minus twice the log-likelihood (−2lnL). The −2lnL under this unrestricted baseline model is then compared with −2lnL under more restrictive biometric models. This yields a likelihood-ratio χ2 test of goodness of fit, which is converted to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; BIC=χ2−Δdf(lnN); N=610 pairs), a fit index that measures model fit relative to parsimony (Raftery, 1995). Better fitting models have smaller BIC values.

RESULTS

There were moderate to large associations across measures of antisocial behavior, both within and across time. The DBI at time 1 was correlated .50 with CD at time 1 and .46 with AAB at time 2. The DBI at time 2 was correlated .32 with CD at time 1 and .53 with AAB at time 2. The means for each measure are presented in Table 1, separately by adoption status. Of the 1,189 participants with CD data, 34.3% reported at least one symptom of CD, and 4.6% reported 3 or more symptoms (i.e., 2.2% of girls and 7.5% of boys). Of those with 3 or more symptoms of CD, 59.9% reported 3 or more symptoms of AAB (as a reminder, 3 symptoms of CD and 3 symptoms of AAB are required for a diagnosis of ASPD).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and sample sizes associated with the antisocial behavior measures.

| Variable | ADOPTIVE YOUTH | NON-ADOPTIVE YOUTH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

| CD1 | 0.50 | 0.95 (n=668) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 0.60 | 1.25 (n=521) | 0.0 | 9.0 |

| DBI1 | 3.02 | 3.57 (n=664) | 0.0 | 20.0 | 2.89 | 3.71 (n=517) | 0.0 | 20.0 |

| AAB2 | 1.08~ | 1.39 (n=529) | 0.0 | 7.0 | 0.93~ | 1.31 (n=406) | 0.0 | 7.0 |

| DBI2 | 4.13* | 4.31 (n=429) | 0.0 | 21.0 | 3.50* | 3.76 (n=323) | 0.0 | 20.0 |

Note. DBI1 and CD1 represent the Delinquency Behavior Index and the Conduct Disorder symptom count at intake, respectively. DBI2 and AAB2 represent the Delinquency Behavior Index and the Adult Antisocial Personality Disorder symptom count at follow-up, respectively. Means, standard deviations, and ranges are presented separately for adoptive and non-adoptive youth. The DBI ranges from 0 to 21, CD ranges from 0 to 14 symptoms, and AAB range from 0 to 7 symptoms.

indicates mean differences across adoption status are significant at p<.05.

indicates mean differences across adoption status are marginally significant at p<.10.

Independent-samples t-tests indicated that adoptive youth reported slightly higher levels of AAB and delinquency than did non-adoptive youth (Cohen’s d = .11 and .16, respectively), results that are consistent with prior research (as reviewed in Keyes, Sharma, Elkins, Iacono, & McGue, 2008; Rueter, Keyes, Iacono, & McGue, 2009). However, this difference was found only at time 2, and was not present at time 1. As expected, self-reported levels of DBI delinquency increased significantly over time in both adoptive and non-adoptive youth (both p<.001). Changes in mean levels of CD/AAB were not examined here, as they cannot be meaningfully compared.

This increasing level of antisocial behavior over time within participants was also observed across participants. In particular, chronological age was positively associated with all measures of antisocial behavior (r’s ranged between .15 and .39, all p<.01). In short, self-reported antisocial behavior increased with age, regardless of the measure examined. Similarly, male youth consistently reported higher levels of antisocial behavior than did female youth (r’s ranged between .17 and .25, all p<.001). The Kruskal-Wallis test (a non-parametric version of a one-way ANOVA) was used to compute the strength of the relationship between the antisocial behavior variables and ethnicity. No association was observed for any variable (p-values ranged from .12 to .92). Given these findings, all subsequent analyses were conducted on age-and sex-residualized scores.

SIBLING SIMILARITY

Prior to multivariate model-fitting analyses, intraclass, within-person, and cross-sibling cross-time correlations were calculated for BIO and ADOP siblings (see Table 2) using the double entry method. The within-person correlations index phenotypic associations across time within each person in the sample. These correlations were moderate to large (i.e., .34 to .56) across sibling-type and diagnostic interview and self-report measures, indicating that antisocial behavior evidences at least a moderate amount of stability over time.

Table 2.

Intraclass Correlations for Biological (BIO) and Adoptive (ADOP) Siblings.

| Measures | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD at time 1 and AAB at time 2 | ||||

| 1. CD, twin A | --- | .42* | .22* | .18* |

| 2. AAB, twin A | .34* | --- | .18* | .32* |

| 3. CD, twin B | .13* | .16* | --- | .42* |

| 4. AAB, twin B | .16* | .23* | .34* | --- |

| DBI at times 1 and 2 | ||||

| 1. DBI at time 1, twin A | --- | .56* | .42* | .29* |

| 2. DBI at time 2, twin A | .51* | --- | .29* | .35* |

| 3. DBI at time 1, twin B | .20* | .15* | --- | .56* |

| 4. DBI at time 2, twin B | .15* | .18* | .51* | --- |

Note. CD, AAB, and DBI represented Conduct Disorder symptoms, Adult Antisocial Personality Disorder symptoms, and the Delinquent Behavior Index, respectively. ADOP sibling correlations are below the diagonals, and BIO sibling correlations are above the diagonals.

The cross-sibling, cross-time correlations are important in the context of the present study, as they permit us to preliminarily examine the origins of stability over time. These correlations were calculated using, for example, the CD symptom count of one sibling and the AAB symptom count of his or her co-sibling. Shared environmental influences on stability are implied by equivalent BIO and ADOP correlations, and by ADOP correlations that are significantly greater than zero. Results are clearly suggestive of shared environmental influences on stability over time, for both CD/AAB and the DBI. The cross-sibling, cross-time correlation for ADOP siblings was significantly greater than zero for both CD/AAB (r = .16) and the DBI (r = .15), highlighting the presence of shared environmentally-mediated stability over time. Moreover, the BIO cross-sibling, cross-time correlations for both CD/AAB and the DBI were statistically equivalent to their corresponding ADOP correlations. Such findings imply that shared environmental influences play an instrumental role in the stability of antisocial behavior over time.

BIVARIATE MODELS

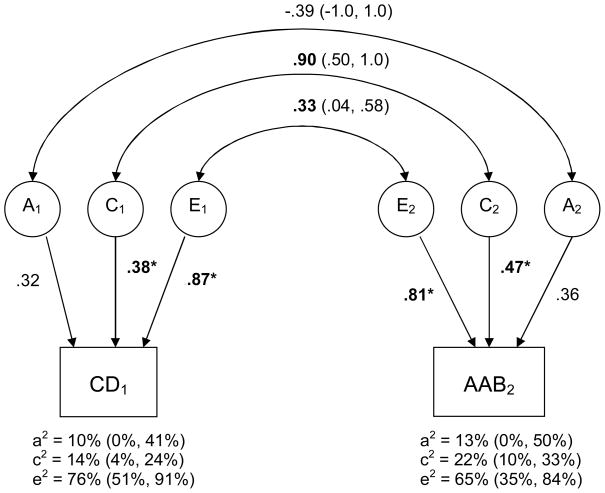

We tested an ACE bivariate model for both CD/AAB and the DBI, in which the variance attributable to genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and non-shared environmental plus measurement error (E) factors were all estimated. We first discuss results for CD/AAB (-2lnL = 5838.45 on 2109 df, BIC = −3840.31).1 As seen in figure 1, genetic influences on CD and AAB were found to be small (10–13% of the variance) and non-significant in these data, suggesting the presence of only minimal genetic effects. By contrast, there were small-to-moderate and significant shared environmental influences on CD and AAB, accounting for 14 – 22% of the variance. Non-shared environmental influences constituted the largest proportion of variance in both CD and AAB, contributing more than 60% of their individual variances.

Figure 1. Standardized Estimates of Additive Genetic (A), Shared Environmental (C), and Non-shared Environmental (E) Contributions to CD and AAB Over Time.

Note. Standardized estimates of the genetic and shared environmental contributions to the variance within and the covariance between Conduct Disorder (CD1) at time 1 and Adult Antisocial Behavior (AAB2; i.e., adult symptoms of ASPD) at time 2 are illustrated. Path coefficients were squared to index the percentage of variance accounted for (these percentages are indicated below their respective phenotypes, followed by their 95% confidence intervals in brackets). * and bold font indicates that the path is significant at p<.05. Genetic and environmental correlations (and their 95% confidence intervals) are indicated via the double-headed arrows in the upper portion of the diagram. Confidence intervals that do not overlap with zero indicate statistical significance at p<.05.

Importantly, however, the pattern of etiological influence at any given time point did not extend to sources of stability over time. The non-shared environmental correlation (rE = .33) was quite small, indicating that only 10.9% (i.e., .332 = 10.9%) of the non-shared environmental influences contributing to CD also contribute to AAB several years later. In other words, the vast majority of these large non-shared environmental effects (i.e., 89.1%) were specific to a given assessment period. The genetic correlation was similarly small and not significant (rA = −.39), indicating that the genetic contributions to CD did not meaningfully overlap with those for AAB. By contrast, the shared environmental correlation was estimated to be .90, suggesting that 81% of the shared environmental effects contributing to CD also contributed to AAB several years later. Moreover, when we computed the proportion of time 2 variance in AAB that is a function of time 1 variance (e.g., rC2 * c22), we found that while non-shared environmental influences on CD accounted for 7.1% of the total phenotypic variance in AAB, shared environmental influences on CD accounted for 17.9%. Such results imply that shared environmental influences, while less prominent than non-shared environmental effects at any given assessment, evidence far more stability over time.

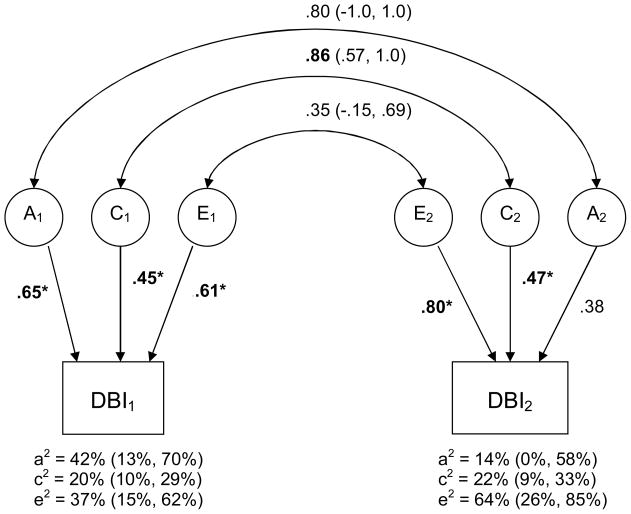

Results were very similar for the DBI (−2lnL = 5163.51 on 1919 df, BIC = −3565.65). As seen in figure 2, genetic influences at times 1 and 2 were found to be small-to-moderate (14 – 42% of the variance), although they were significantly greater than zero only at time 1. Shared environmental influences, by contrast, were found to be consistently moderate in magnitude, accounting for 20–22% of the variance. Non-shared environmental influences were again rather large, particularly at time 2, where they accounted for 64% of the variance. As before, however, the pattern of etiological influence on the DBI at any given time point did not extend to its stability over time. Neither the genetic nor the non-shared environmental correlations were significantly greater than zero, indicating that these effects do not meaningfully persist over time. Indeed, the vast majority of non-shared environmental effects (i.e., 87.7%) were found to be specific to a given assessment period. The shared environmental correlation, by contrast, was estimated to be .86, suggesting that 74% of the shared environmental effects contributing to the DBI persisted over time. Finally, when we computed the proportion of DBI variance at time 2 that is a function of time 1 variance, we again found that while non-shared environmental influences at intake accounted for 7.8% of the total phenotypic variance at follow-up, shared environmental influences at intake accounted for 16.3%.

Figure 2. Standardized Estimates of Additive Genetic (A), Shared Environmental (C), and Non-shared Environmental (E) Contributions to Delinquency Over Time.

Note. DBI1 and DBI2 represent delinquency, as assessed via the Delinquency Behavior Index, at times 1 and 2, respectively. Standardized estimates of the genetic and shared environmental contributions to delinquency over time are illustrated. Path coefficients were squared to index the percentage of variance accounted for (these percentages are indicated below their respective phenotypes, followed by their 95% confidence intervals in brackets). * and bold font indicates that the path is significant at p<.05. Genetic and environmental correlations (and their 95% confidence intervals) are indicated via the double-headed arrows in the upper portion of the diagram. Confidence intervals that do not overlap with zero indicate statistical significance at p<.05.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of the present study was to examine the persistence (or lack thereof) of shared and non-shared environmental influences on adolescent antisocial behavior over time in a longitudinal sample of biological and adoptive sibling pairs. We examined two measures of these behaviors, each based on a different assessment strategy: the self-report DBI questionnaire and an in-person interview assessing child and adult symptoms of Antisocial Personality Disorder. Results revealed that, as predicted, the shared environment made important contributions to the stability of antisocial behavior over time, and did so across both measures of antisocial behavior. Most shared environmental influences present at time 1 were also present at time 2 (i.e., 74–81%), whereas the vast majority of non-shared environmental influences (88–89%) were specific to a given assessment period. Furthermore, shared environmental influences present at time 1 accounted for 16–18% of the total phenotypic variance in antisocial behavior at time 2, while non-shared environmental influences present at time 1 accounted for only 7–8% of the total variance at time 2. Such results provide an important extension of previous twin and adoption studies (Bartels et al., 2004; Huizink et al., 2007; van der Valk, et al., 1998), as they firmly suggest that passive genotype-environment correlations, common experiences of trauma, and shared informant effects do not explain earlier findings of shared environmental stability over time. Instead, shared environmental influences on adolescent antisocial behavior appear to relatively persistent and systematic in nature.

There are several limitations to bear in mind when interpreting the results of this study. First, although the reporting periods for CD/AAB did not overlap across assessments, it is unclear whether this also applies to the DBI. In particular, participants were asked to report on DBI behaviors “during adolescence”. It is thus possible that participants were reporting on some of the same actions at both assessments. That said, mean level of the DBI did increase over time, suggesting that not all behaviors overlap across the two assessments. Moreover, the DBI results are fully consistent with those for CD/AAB. We thus conclude that our core conclusions are unlikely to be a function of overlapping reporting periods.

Second, gender was regressed out of CD/AAB and the DBI prior to analysis. Prior meta-analyses (Burt, 2009a; Rhee & Waldman, 2002) have indicated that heritability estimates for antisocial behavior do not generally vary across gender, suggesting that our decision to exclude gender is unlikely to have impacted our results. That said, our measures did not include relational aggression, a form of aggression thought to have a higher prevalence in girls than boys, and one for which genetic and environmental contributions have only rarely been examined (Brengden et al., 2008). Future analyses should incorporate analyses of relational aggression and gender into explorations of shared environmental influences. Next, the current results apply only to adolescence/emerging adulthood and not to other developmental periods, as there is some suggestion that the heritability of antisocial behavior may vary by age/age-of-onset (Moffitt, 2003). It thus remains unclear whether these findings would generalize to earlier or later developmental stages.

Next, although our finding of small and generally non-significant genetic influences (and correspondingly non-significant genetic correlations) is consistent with those in other sibling adoption studies (Burt, 2009b), such findings stand in sharp contrast to the moderate-to-large genetic effects on antisocial behavior typically reported in twin studies (e.g., typically 40–60%; Burt, 2009a; Rhee & Waldman, 2002). Importantly, however, this general pattern of differences across twin and adoption studies is quite common. A recent meta-analysis of child and adolescent psychopathology (Burt, 2009b) reported genetic estimates of 52% in twin studies and 23% in adoption studies (as averaged across all forms of child and adolescent psychopathology; for conduct problems in particular, the genetic estimate was 58% in twin studies and 37% in adoption studies). Although the reasons behind these differences remain unclear, one possibility is that the inclusion of genetically-identical siblings (i.e., monozygotic twins) increases our ability to detect genetic influences.

Similarly, although there is evidence of significant genetic influence on the DBI at time 1 (i.e., 42%), genetic influences on CD were small and not significant (i.e., 10%). This is somewhat peculiar, given that these two measures of antisocial behavior were both administered at time 1, and moreover, were correlated .50. Although the reasons for this difference remain unclear, it is worth noting that recent meta-analytic work (Burt, 2009b) has indicated that heritability estimates are often lower, and non-shared environmental influences higher, when the phenotype is assessed using diagnostic interviews as compared to questionnaires. As outlined in Burt (2009b), such results could reflect an increase in measurement error for diagnostic interviews (since measurement error is contained within e2), as questionnaires have forced choice responses that are likely to improve reliability. Alternately, they could reflect differences in skew across the two assessment methods. Questionnaires often assess both normative and deviant ranges of the trait in question, whereas diagnostic interviews assess only clinically-significant symptoms, resulting in a “floor effect” and prominent skew (i.e., most participants have symptom counts close to the low end of the scale). Lastly, rather that reflecting measurement error of some kind, these differences could reflect true differences in genetic and environmental influences across severity, such that non-shared environmental influences are more etiologically salient for those with more disturbed functioning. Future research should explore these various possibilities.

Finally, although the adoptive youth in this sample were generally placed in their adoptive homes quite early in life (mean = 4.8 months of age), there was some variability in age of placement (SD = 4.7 months). As we do not have information on the pre-placement experiences of adoptive youth in our sample, it is possible that some may have experienced aversive/traumatic events (i.e., inconsistent caregiving, neglect, etc.) prior to their placement in the adoptive home. Should these trauma experiences be shared across adoptive siblings, they may be driving our findings of shared environmental persistence over time. To rule out this possibility, analyses were re-run restricting the ADOP pairs to adoptive/biological siblings pairs only (the latter of whom were not adopted and so did not have “ pre-placement” experiences, n=124 families). The results were essentially identical to those reported here. Shared environmental correlations were estimated to 1.0 for both the DBI and CD/AAB, whereas non-shared environmental correlations were smaller (.41 and .28, respectively) and non-significant. As common pre-placement trauma experiences cannot contribute to sibling similarity in these supplemental analyses, such findings buttress our conclusion that shared environmental influences persist over time regardless of common pre-placement trauma experiences in adoptive siblings.

Despite these limitations, the current study has important implications for both the origins of antisocial behavior and for future etiological research on child and adolescent psychopathology more generally. Behavioral genetic research has historically concluded that the more important environmental influences on psychological and behavioral outcomes result in differences between siblings (Plomin & Daniels, 1987), a conclusion that continues to influence theory and interpretation of environmental influences up to the present day. More recent research, however, has suggested moderate influences of the shared environment on child and adolescent psychopathology, including antisocial behavior (Burt, 2009b). It has also been argued that, unlike non-shared environmental effects (Rutter et al., 1999; Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000), shared environmental influences are both identifiable and persistent over time (Burt, 2009b). Unfortunately, prior studies of the stability of shared environmental influences suffered from some key interpretative limitations, namely possible passive rGE, shared informants effects, and/or common experiences of trauma. The current study addressed each of these limitations. Results remained consistent with prior findings suggesting a very high level of shared environmental stability over time.

By contrast, non-shared environmental influences were found to be largely specific to each assessment period. Such findings build on prior literature to further suggest that while shared environmental effects are often a function of relatively persistent, systematic influences, non-shared influences are largely idiosyncratic and unsystematic in nature (Burt, et al., 2006; Rutter et al., 1999; Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000). Though this sort of reconceptualiztion diminishes the hypothesized importance of the non-shared environment (Plomin & Daniels, 1987), it does not follow that temporally-specific (i.e., within-age, cross-trait) associations are necessarily meaningless. Rather, they may play a role in transiently shaping the adolescent’s experience and behaviors at a given age (Turkheimer & Waldron, 2000), experiences that may compound over time to alter individual outcomes (Plomin & Asbury, 2005). Future research should further explore shared and non-shared environmental influences on child and adolescent psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by USPHS Grants # AA11886 and MH066140.

Footnotes

To better examine whether our results were impacted by the different symptoms of ASPD assessed as part of CD and AAB, we re-ran our analyses restricting the data to those behaviors that were “common” across the CD and AAB assessments (i.e., CD: stolen without confrontation, lying, fighting, cruelty to others, fighting with a weapon, destroying property, and breaking and entering; AAB: illegal acts, irritability and aggression, impulsivity, and reckless disregard for safety; phenotypic r = .42). Results were notably consistent to those reported above. The non-shared environmental correlation (rE = .50) indicated that most non-shared environmental variance (75%) did not persist over time. By contrast, the shared environmental correlation was estimated to be 1.0 (95% CI = .65–1.0), suggesting that 100% of the shared environmental effects contributing to CD also contributed to AAB. Such results imply that, regardless of the operationalization of CD/AAB, shared environmental influences evidence more stability over time than do non-shared environmental influences.

References

- Bartels M, van den Oord EJCG, Hudziak JJ, Rietveld MJH, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Boomsma DI. Genetic and environmental mechanisms underlying stability and change in problem behaviors at ages 3, 7, 10, and 12. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:852–867. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brengden M, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM, Dionne G, Tremblay RE, et al. Linkages between children’s and their friends’ social and physical aggression: Evidence for a gene-environment interaction? Child Development. 2008;79:13–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JP, McGue M, Keyes MA, Iacono WG. Are there shared environmental influences on adolescent behavior? Evidence from a study of adoptive siblings. Behavior Genetics. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9283-y. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Are there meaningful etiological differences within antisocial behavior? Results of a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009a;29:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009b;135:608–637. doi: 10.1037/a0015702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Barnes AR, McGue M, Iacono WG. Parental divorce and adolescent delinquency: Ruling out the impact of common genes. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1668–1677. doi: 10.1037/a0013477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Donnellan MB. Personality correlates of aggressive and non-aggressive antisocial behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG. Parent-child conflict and the comorbidity among childhood externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:505–513. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger RF. Differential Parent-child Relationships and Adolescent Externalizing Symptoms: Cross-Lagged Analyses within a Twin Differences Design. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1289–1298. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Environmental contributions to adolescent delinquency: A fresh look at the shared environment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:787–800. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Maes HH, Silberg JL, Eaves LJ. A children of twins study of parental divorce and offspring psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:667–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PAF, et al. A genetically informed study of marital instability and its association with offspring psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:570–586. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Silberg JL, JMM, Maes HH, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: 2. The main effects of genes and environment on behavioral problems in the Virginia twin study of adolescent development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:965–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, West DJ. A comparison between early delinquents and young aggressives. British Journal of Criminology. 1971;11:341–358. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson HB. Self-report delinquency among school boys and their attitudes towards police. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;20:303–315. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, van den Berg MP, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Longitudinal genetic analysis of internalizing and externalizing problem behavior in adopted biologically related and unrelated sibling pairs. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:55–65. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Sharma A, Elkins IJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. The mental health of US Adolescents adopted in infancy. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:419–425. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Hay D. Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:371–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, et al. The environment of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence of range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behavioral Genetics. 2007;37:449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Sharma A, Benson P. The effect of common rearing on adolescent adjustment: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:604–613. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: A research review and a research agenda. In: Lahey B, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. The causes of conduct disorder and serious juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical Modeling. 6 VCU Box 900126, Richmond, VA 23298: Department of Psychiatry; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington EM. The Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development (NEAD) Project: A Longitudinal Family Study of Twins and Siblings from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:74–83. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Pedersen N, Lichtenstein P, Spotts EL, Hansson K, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on mothering of adolescents: A comparison of two samples. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:335–351. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Conner TG, McGuire S, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, Plomin R. Co-occurence of depressive symptoms and antisocial behavior in adolescence: A common genetic liability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:27–37. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Caspi A, DeFries JC, Plomin R. Are associations between parental divorce and children’s adjustment genetically mediated? An adoption study. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike A, McGuire S, Hetherington EM, Reiss D, Plomin R. Family environment and adolescent depressive symptoms and antisocial behavior: A multivariate genetic analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:590–603. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Asbury K, Dunn J. Why are children from the same family so different? Nonshared environment a decade later. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;46:225–233. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Daniels D. Why are children in the same family so different from one another? Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1987;10:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reich W. Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:14–15. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renk K. Disorders of conduct in young children: Developmental considerations, diagnoses, and other characteristics. Developmental Review. 2008;28:216–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueter MA, Keyes MA, Iacono WG, McGue M. Family interactions in adoptive compared to nonadoptive families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:58–66. doi: 10.1037/a0014091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Silberg J, O’Connor TJ, Simonoff E. Genetics and child psychiatry: I Advances in quantitative and molecular genetics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, McGue MK, Iacono WG. Twin concordance for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A comparison of teachers’ and mothers’ reports. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:532–535. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg J, Rutter M, Meyer J, Maes H, Hewitt J, Simonoff E, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on the covariation between hyperactivity and conduct disturbance in juvenile twins. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1996;37:803–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Dinwiddie SH, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Dunne MP, et al. Modeling genetic and environmental influences in the etiology of conduct disorder: A study of 2,682 adult twin pairs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:266–279. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Division; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M. Correcting estimates of shared environmental variance for range restriction in adoption studies using a truncated multivariate normal model. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:429–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1021685211674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E, Waldron M. Nonshared environment: A theoretical, methodological, and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:78–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk JC, Verhulst FC, Neale MC, Boomsma DI. Longitudinal genetic analysis of problem behaviors in biologically related and unrelated adoptees. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28(5):365–380. doi: 10.1023/a:1021621719059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung K, Amado H. Reliability, validity, and parent-child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26:649–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]