Abstract

Mitochondria carry many copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), but mt-alleles quickly segregate during mitotic growth through unknown mechanisms. Consequently, all mtDNA copies are often genetically homogeneous within each individual (“homoplasmic”). Our previous study suggested that tandem multimers (“concatemers”) formed mainly by the Mhr1p (a yeast nuclear gene-encoded mtDNA-recombination protein)-dependent pathway are required for mtDNA partitioning into buds with concomitant monomerization. The transmission of a few randomly selected clones (as concatemers) of mtDNA into buds is a possible mechanism to establish homoplasmy. The current study provides evidence for this hypothesis as follows: the overexpression of MHR1 accelerates mt-allele-segregation in growing heteroplasmic zygotes, and mhr1-1 (recombination-deficient) causes its delay. The mt-allele-segregation rate correlates with the abundance of concatemers, which depends on Mhr1p. In G1-arrested cells, concatemeric mtDNA was labeled by [14C]thymidine at a much higher density than monomers, indicating concatemers as the immediate products of mtDNA replication, most likely in a rolling circle mode. After releasing the G1 arrest in the absence of [14C]thymidine, the monomers as the major species in growing buds of dividing cells bear a similar density of 14C as the concatemers in the mother cells, indicating that the concatemers in mother cells are the precursors of the monomers in buds.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria carry variable and large numbers of genomic DNA copies, e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells contain 30–100 copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). mtDNA is essential to mitochondrial functions. Mutations are acquired by the mitochondrial genome ∼10 times faster than the nuclear genome (Brown et al., 1979), and thus it would be supposed that each cell contains heterogeneous mtDNA copies with various mutations. Unlike the nuclear genome, the alleles of the mitochondrial genome often quickly segregate during mitotic cell cycles, and within 10–20 mitotic cell cycles in Saccharomyces yeast (for reviews, see Birky, 1978; Dujon, 1981), all of the mtDNA within each cell becomes genetically homogeneous (“homoplasmic”; Figure 1A). Heteroplasmy in humans is generally observed in association with serious hereditary diseases known as mitochondrial diseases, and in some tissues of aged individuals (for reviews, see Lightowlers et al., 1997; Shoubridge, 1998).

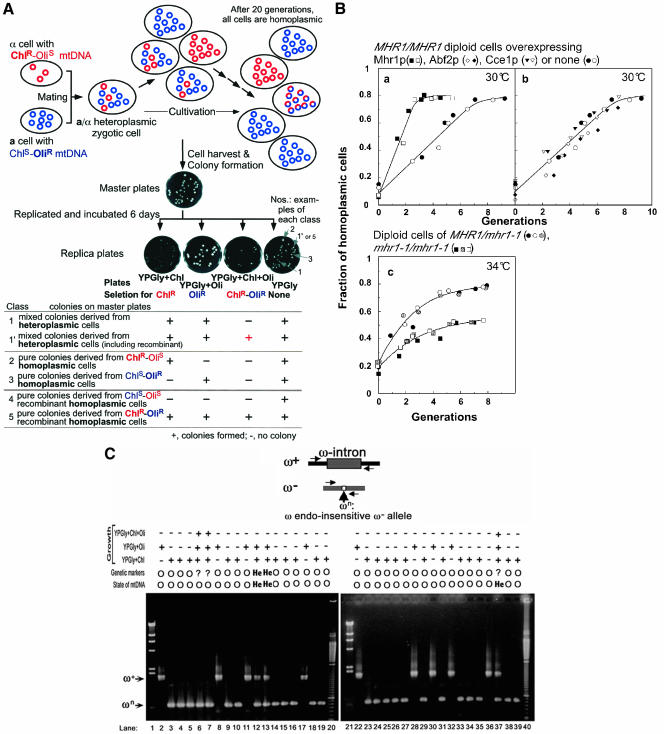

Figure 1.

Active roles of Mhr1p in vegetative segregation to generate homoplasmic cells. (A) The concept of vegetative segregation and homoplasmy, and a genetic assay for homoplasmy. Heteroplasmic cells are generally created by a mutation, and in yeasts and fungi (not in mammals), they are reproducibly created by mating cells with different sets of mitochondrial alleles, as shown in this figure. Unlike the nuclear alleles, which are segregated at 1:1 mostly through meiosis (Mendelian segregation), all alleles are segregated during 10–20 generations of vegetative growth, and finally, in each of the progeny, all of the mtDNA copies have the same sequence (the same set of alleles). In this study, heteroplasmic cells were obtained by mating α-cells (mt[ChlR-OliS] and a-cells (mt[ChlS-OliR], and only diploid zygotes were allowed to grow at 30°C or 34°C. Samples of the culture were withdrawn, diluted, and spread on SD plates to form colonies. The colonies on the master plate were replicated onto four YPGly plates, with or without chloramphenicol and/or oligomycin. The colonies on the master plates were classified according to the criteria shown in the Table in this figure, and the total fraction of colonies in classes 2 through 4 among all of the colonies was calculated as the fraction of homoplasmic cells. Colonies of class 5 homoplasmic cells cannot be distinguished from those in class 1′ heteroplasmic cells by this assay, but the fraction was very small and can be ignored within the first five generations (see text). YPGly+X indicates a YPGly plate supplemented with antibiotics X (Chl and Oli indicate chloramphenicol and oligomycin, respectively). +, cells form colonies; -, cells do not form colonies. Circles represent each unit size mtDNA copy. Blue symbols and red symbols represent mtDNA (or alleles) derived from a-cells (mt[ChlS-OliR] and mtDNA (or alleles) derived from α-cells (mt[ChlR-OliS], respectively. Circles with a red part and a blue part represent a unit size copy of recombinant mtDNA. (B) A genetic assay for mtDNA homoplasmy, and the effects of the in vivo activity of Mhr1p on vegetative segregation. The calculated fractions of homoplasmic cells are plotted against the generation time of zygotes at 30°C or 34°C. Closed, shadowed, crossed, slashed, and open symbols indicate data from independent experiments. Each panel contains at least two independent series of experiments. a and b, cells overexpressing the indicated protein at 30°C in GalSR medium. Circles, diploids of parental strains (YKN1423/pYES2 × W303a-187); squares, diploids overproducing Mhr1p (YKN1423/pYESMHR1 × W303aGalMHR1); inverted triangles, diploids overproducing Cce1p (W303aGalCCE1 × W303a GalCCE1); diamonds, diploids overproducing Abf2p (W303aGalABF2 × W303a Gal-ABF2). Cells without an overexpression plasmid grew with a generation time of ∼1.2 h without a lag at 30°C. c, cells grown at 34°C in SD medium. Circles, MHR1/mhr1-1 diploids (YKN1423 × FL67-2c); squares, mhr1-1/mhr1-1 diploids (FL67-1423 × FL67--2c). The cells grew with a generation time of 1.2 h for both MHR1/mhr1-]1 cells and mhr1-1/mhr1-1 cells, without any apparent lag. (C) A PCR assay for mtDNA homoplasmy. Thirty-two colonies of diploid cells, derived from a cross between YKN1423 (α, ω+, Oli1R) and 55R5-C1(a, ωn, Chl321R) cells, were randomly selected from the master plate. Cells from each colony were propagated and whole cellular DNA was prepared. The DNA fragments containing the ω locus were amplified by PCR and were analyzed by electrophoresis. At the top, schematic physical maps at the ω+ (contains the ω-intron) and ω- (ω-intron-less) loci on mtDNA are indicated. ωn is a cis mutation at the ω- locus that prevents the cleavage by the ω endonuclease. Pairs of horizontal arrows in the drawing indicate the primers used for PCR. Homoplasmic or heteroplasmic cells, as determined by the genetic assay and the PCR-based DNA assay, are indicated as O (homoplasmic), He (heteroplasmic), and? (uncertain). Lanes 4–19 and lanes 24–39, yeast DNA samples. Controls, lanes 2 and 22, YKN1423 (ω+, Oli1R); lanes 3 and 23, 55R5-C1(ωn, Chl321R). Lanes 1 and 21, λ DNA HindIII-digests; lanes 20 and 40, 100-bp DNA ladder. Arrows indicate the positions of ω+ and ωn.

In the establishment of mutant homoplasmic cells, the mutant allele on a single copy of mtDNA propagates to the entire population of multiple organelle DNA copies in the cells, as if a copy of randomly selected mtDNA is used as the template for the replication of all progeny mtDNA. If one assumes that each mtDNA replicates independently and is randomly segregated into progenies, then the number of mtDNAs should be two to six, or approximately three in each mitotic yeast cell (Birky, 1978; Dujon, 1981). The calculated numbers of mtDNA copies are much smaller than the actual copy numbers of mtDNA. Thus, the homoplasmic cells are generated by a nonrandom process. Although a number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain the mechanisms, no protein or gene has been identified that plays a role in the process of generating homoplasmic cells from heteroplasmic ones, as far as we know.

Studies on the mechanisms of the production of homoplasmic cells from heteroplasmic ones require sufficient amounts of reproducible heteroplasmic cells. In the yeast S. cerevisiae (not in mammals), heteroplasmic cells are reproducibly and efficiently created by the mating of haploid yeast cells carrying different mitochondrial alleles, and all of the heteroplasmic zygotes become homoplasmic within a few tens of generations (Figure 1A; for review, see Dujon, 1981). In addition, various genetic and molecular biological techniques and resources are available in this organism. Thus, S. cerevisiae provides a good model system for studying homoplasmy.

MHR1 is a gene originally isolated as being required for mitochondrial DNA recombination (Ling et al., 1995) and DNA repair (Ling et al., 2000) in S. cerevisiae. Our recent study (Ling and Shibata, 2002) revealed that the gene product (the Mhr1 protein, indicated as Mhr1p) has an activity to pair homologous single-stranded DNA and double-stranded DNA to form heteroduplex joints (general intermediates of homologous DNA recombination; Holliday, 1964). In addition, we showed that head-to-tail tandem linear multimers (“concatemers”) are predominant in mother cells and nondividing cells, but circular monomers are the major form of mtDNA in growing buds (Ling and Shibata, 2002). The in vitro activity of Mhr1p, the requirement for Mhr1p in mtDNA partitioning, and the difference in the size distribution between the mtDNA in mother cells and that in growing buds suggest that in yeast mitochondria, mtDNA concatemers formed mainly by the Mhr1p-dependent pathway (likely rolling circle replication) are essential intermediates that are processed into circular monomers upon mtDNA partitioning (Ling and Shibata, 2002).

The transmission of clones (as concatemers) of mtDNA replicated in a rolling circle mode on a few randomly selected templates into buds would explain how homoplasmy is established quickly. Therefore, we conducted a series of experiments to test this hypothesis. The results obtained in this study provide evidence for this hypothesis, but do not support other possible explanations for the establishment of homoplasmy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains and Media

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1, and the media were reported or described previously (Ling et al., 1995; Nunnari et al., 1997; Ling and Shibata, 2002).

Table 1.

Yeast strains

| Strains | Nuclear genotype plasmid (genotype) | [Mitochondrial genotype] | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFS98 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+] | Nunnari et al. (1997) | ||

| AFS98ρ0 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ0] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| AFS98-4a | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK mhr1-1 | ||

| [ρ+] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| AFS98-pMK2 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK MHR1 | ||

| [ρ- pMK2 in mitochondria] | This study | ||

| AFS984a-pMK2 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK mhr1-1 | ||

| [ρ- pMK2 in mitochondria] | This study | ||

| AFS984a-pMK2/pYESTrp1 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK mhr1-1 | ||

| pYESTrp1 (TRP1) | [ρ- pMK2 in mitochondria] | This study | |

| AFS984a-pMK2/pYESTrp1MHR1 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1::GPD-HSVTK mhr1-1 | ||

| pYESTrp1MHR1 (MHR1, TRP1) | [ρ- pMK2 in mitochondria] | This study | |

| FL67-1423 | α his1 trp1 can1 mhr1-1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling et al. (1995) | ||

| FL67-2c | aleu2 trp1 can1 mhr1-1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling et al. (1995) | ||

| IL166-6b | aleu2 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling et al. (1995) | ||

| IL166-6b-ccel::LEU2 | aleu2 ura3 trp1 can1 cce1::LEU2MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| pTY24 | aade2 leu2 ura3 MHR1 | [ρ- pMK2 in mitochondria] | Thorsness et al. (1990) |

| YKN1423 | α leu2 ura3 met3 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling et al. (1995) | ||

| YKN1423/pYES2 | α leu2 ura3 met3 MHR1 | ||

| pYES2 (URA3) | [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | |

| YKN1423/pYESMHR1 | α leu2 ura3 met3 MHR1 | ||

| pYESMHR1 (MHR1, URA3) | [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | |

| YKN1423-ccel::LEU2 | α leu2 ura3 met3 cce1::LEU2 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303a | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+] | Nunnari et al. (1997) | ||

| W303a-187 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303a/pYES2 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| pYES2 (URA3) | [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | |

| W303a/pYESMHR1 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 | ||

| pYESMHR1 (MHR1, URA3) | [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | |

| W303aGalABF2 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 can1 MHR1 GalABF2 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303aGalCCE1 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 can1 MHR1 GalCCE1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303aGalMHR1 | aade2 leu2 his3 ura3 can1 GalMHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ens2 Chl321R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303α | α ade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+] | Nunnari et al. (1997) | ||

| W303α/pYESMHR1 | α ade2 leu2 ura3 his3 trp1 can1 | ||

| pYESMHR1 (MHR1, URA3) | [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | |

| W303α-1423 | α ade2 leu2 his3 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303αGalCCE1 | α ade2 leu2 ura3 can1 MHR1 GalCCE1 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| W303αGalABF2 | α ade2 leu2 ura3 trp1 can1 MHR1 GalABF2 | ||

| [ρ+ ω+ Δens2 Oli2R] | Ling and Shibata (2002) | ||

| 55R5-C1 | a,his1 | ||

| [ρ+ ωn, Chl321R] | This study |

A genetic Assay for the Vegetative Segregation of Mitochondrial Alleles to Generate Homoplasmic Cells

The genetic assay is illustrated in Figure 1A. Heteroplasmic cells were formed by mating haploid cells with unlinked mitochondrial antibiotic-resistance markers, i.e., α-cells carrying mitochondrial ChlR (chloramphenicol-resistance)-OliS (oligomycin-sensitive) alleles and a-cells carrying mitochondrial ChlS-OliR alleles were mixed at 2.0 × 107 cells/ml each in YPD or YPGal medium for 5 h at 30°C to form zygotes (which are heteroplasmic and carry both ChlR-OliS and ChlS-OliR mtDNA). To terminate mating, protease (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; to digest mating factors) was added to the medium at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml, and the cultures were incubated for 6 h at 30°C. The mated cells were then diluted 100-fold into liquid SD supplemented with the required amino acids, to allow only the growth of diploid zygotes at 30°C (standard) or 34°C (a sublethal temperature for mhr1-1/mhr1-1 cells). The SD medium was replaced by GalSR medium to overproduce Mhr1p by galactose-induction of the GAL1 promoter, under which MHR1 was regulated. Samples of the culture were withdrawn at intervals, diluted, and spread on SD plates. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 23°C to allow the selective colony-formation of only diploid cells. Each colony on the SD plates (master plates) was classified according to the criteria shown in the table in Figure 1A, by replica plating as follows: colonies on the SD plate (master plate) were replicated onto YPGly plates containing chloramphenicol (4 mg/ml), YPGly plates containing oligomycin (3 μg/ml), YPGly plates containing both chloramphenicol and oligomycin, and YPGly plates without antibiotics. Colonies were allowed to form on the replicated plates at 23°C. During colony formation on the master plate, all of the cells in each colony became homoplasmic, regardless of the mitochondrial genotype of the original cell. Thus, each colony derived from a heteroplasmic cell contains both cells with a-parental mtDNA and cells with α-parental mtDNA (class 1), and sometimes contains cells with recombinant mtDNA (class 1′), and each colony derived from a homoplasmic cell purely contains cells with either parental mtDNA (classes 2 and 3) or a single type of recombinant mtDNA (classes 4 and 5). The total fraction of colonies in classes 2 through 4 among all of the colonies was calculated as the fraction of homoplasmic cells. It is noted that this genetic assay does not distinguish class 1′ heteroplasmic cells and class 5 homoplasmic cells.

A Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Assay for Homo- and Heteroplasmic mtDNA

Colonies formed by cells harvested at 5 h of growth (∼4 generations) at 30°C, after crossing YKN1423 (ω+, Oli1R) and 55R5-C1(ωn, Chl321R) cells, were randomly selected from the master plate. Cells from each colony were propagated, and whole cellular DNA was prepared. The DNA fragments containing the ω locus were amplified by using the KOD DNA polymerase kit (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan). The isolation of DNA, the design of primers used in PCR, and the conditions for PCR and electrophoresis were described previously (Ling et al., 1995).

The Construction of Vectors Overproducing the Mhr1 Protein, the mhr1-1 Protein, the Cce1 Protein, and the Abf2 Protein

MHR1, mhr1-1, CCE1, and ABF2, each under the control of the GAL1 promoter, were overexpressed in yeast by adding galactose to the medium. The open reading frame (ORF) of each gene was placed behind the GAL1 promoter on the yeast overexpression vector pYES2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or pYES2Trp1, constructed by substituting TRP1 for URA3 in pYES2, or on the nuclear chromosome as described previously (Longtine et al., 1998). Proteins expressed in yeast were detected by immunoblot analyses (Towbin et al., 1979).

Analyses of mt-pMK2 DNA Isolated from Cells by Standard One (1D) or Two-dimensional (2D) Gel Electrophoresis

Whole DNA, isolated from MHR1 cells (AFS98-pMK2), mhr1-1 cells (AFS984apMK2) with mitochondrial (mt-) pMK2 DNA or r0 cells (cells devoid of mtDNA; AFS98 ρ0) was separated by standard gel electrophoresis, which was run for 48 h at 1 V/cm on a 0.5% agarose gel in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 23°C.

The two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was basically carried out as described previously (Lockshon et al., 1995). The first dimension was run for 20 h at 1 V/cm on a 0.4% agarose gel in TBE buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 23°C. The 5-kb λ ladder DNA size markers were used (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The second dimension was run at 5 V/cm on a 1% agarose gel in TBE buffer with 0.3 μg/ml ethidium bromide at 4°C. The DNA in the gel was transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) in 10× SSC (1.5 M NaCl, 0.15M sodium citrate) by capillary blotting and was analyzed by a Southern hybridization with 32P-labeled pUC119 DNA, which shares some sequence with pMK2 DNA and thus can be used as a specific probe. The DNA species on the two-dimensional gel were assigned as described previously (Backert, 2002).

For the quantification of the 32P signals from linear concatemers, the gross signals occurring in area c (indicated in Figures 2, B and C, and 3B) were simply corrected by the background signals of the same size of an area lacking radioactivity. For the quantification of the 32P (or 14C) signals from the circular monomers in the 1D gel electrophoresis shown in Figures 2B, 3B, 5, C and D, we did the following corrections, because in 1D electrophoresis, the area m (Figures 2B and 3B) or “monomers” (Figure 5, C and D) for circular monomers also contains, in addition to the signals from circular monomers, the signals of similarly sized linear DNA, as indicated in the two-dimensional gel shown in Figure 2, C and D (m for circular monomer and 1 for linear monomer exhibit the similar migration distance in the first dimensional run). As shown in Figure 2D, linear DNA exists in a continuous distribution of various sizes. Thus, for the calculation of net signals from circular monomers, the average of the signals occurring in the same amount of area just above and below the area m (or that for “monomer”) was subtracted from the gross signals in the area m (or that for monomer). Without this correction, the signals occurring in area m in Figure 2B were significantly overestimated, compared with those of the circular monomeric mtDNA in Figure 2D.

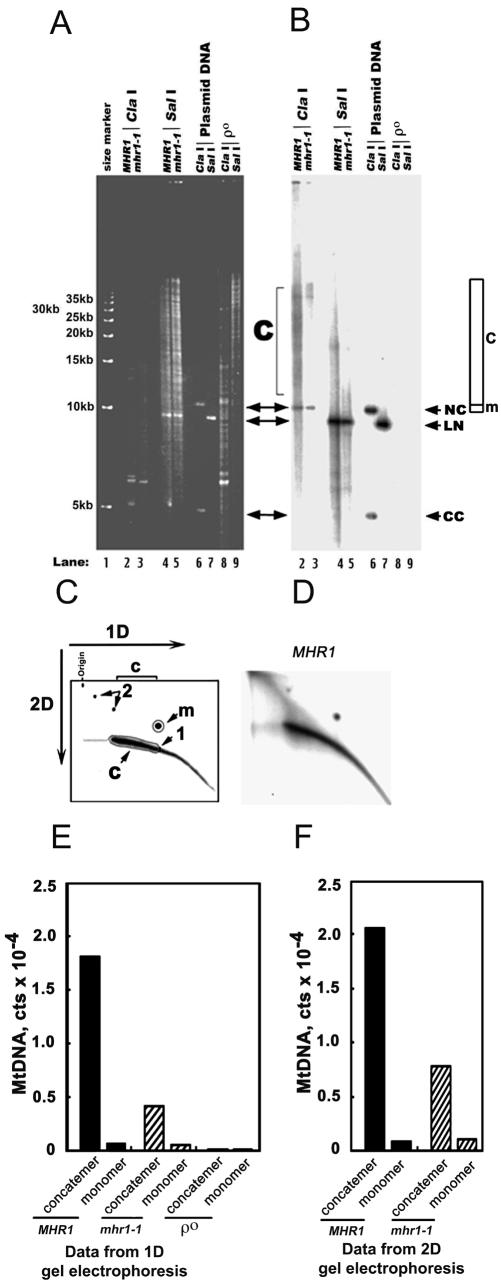

Figure 2.

mhr1-1 prevents concatemer formation at 34°C. (A and B) One-dimensional gel electrophoretic analysis of mt-pMK2 DNA. The MHR1 (lanes 2 and 4) and mhr1-1 (lanes 3 and 5) cells with t-pMK2 DNA (AFS98-pMK2 [MHR1] and AFS984a-pMK2 [mhr1-1]) and ρ0 cells (mtDNA-less cells; AFS98 ρ0; lanes 8 and 9) were grown in YPD at 34°C from 1.0 × 105 cells/ml to 5.0 × 107 cells/ml. Whole DNA was isolated and treated with the restriction endonuclease ClaI (no cleavage site in pMK2 DNA; lanes 2, 3, and 8) or the restriction endonuclease SalI (a single cleavage site in pMK2 DNA; lanes 4, 5, and 9). Then, the treated DNA was analyzed by one-dimensional electrophoresis as described previously (Lockshon et al., 1995; Ling and Shibata, 2002). CC, closed circular monomer; LN, linear monomer; NC and m (region), nicked circular monomer; c (region), concatemers. Lanes 6 and 7, the isolated plasmid pMK2 DNA treated with the restriction endonucleases ClaI and SalI, respectively. Lane 1, 5-kb ladder as a size marker. (A) Gel stained with ethidium bromide. (B) Signals from mt-pMK2 DNA obtained by Southern hybridization by using the [32P]pMK2 DNA-probe. (C and D) Two-dimensional gel electrophoretic analysis of mt-pMK2 DNA. Whole cellular DNA was isolated and treated to digest the nuclear chromosomal DNA by the restriction endonuclease ClaI (no cleavage site in pMK2 DNA) as described in A and B. The mt-pMK2 DNA was detected by Southern hybridization by using the [32P]pMK2 DNA-probe, after separation by size in the first dimensional electrophoresis and by shape in the second dimensional run. (C) Schematic diagram; 1, linear monomer; m (area), nicked circular monomer; 2, circular multimers; c (area), linear concatemers (see Backert, 2002 for the assignments of DNA species); 1D, the first dimensional run; 2D, the second dimensional run. (D) The two-dimensional gel profile of the mt-pMK2 DNA isolated from MHR1 cells grown at 34°C. (E and F) Quantification of the signals in one-dimensional and two-dimensional gels. Based on the Southern hybridization experiment, the 32P signals from circular monomers (indicated as monomer) and linear concatemers (indicated as concatemer) in B and D were plotted. The overlap of signals from linear DNA with the signals from circular monomers in 1D gel electrophoresis (E) was corrected as described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS. The absolute numbers of the signals of each DNA species varied between the experimental series, but the relative signals of concatemers to circular monomers were reproducible as follows: the ratio of concatemers to circular monomers was 27.2 ± 1.8 in the MHR1 cells and 7.8 ± 0.5 in the mhr1-1 cells (each calculated from two independent experiments by using one-dimensional gels, and two independent experiments using two-dimensional gels). Concatemer, linear concatemeric mt-pMK2 DNA; monomer, circular monomers of mt-pMK2 DNA.

Figure 3.

Overproducing Mhr1p enhances concatemer formation in mhr1-1 cells at 34°C. (A and B) One-dimensional gel electrophoretic analysis of mt-pMK2 DNA. The AFS984a-pMK2 (mhr1-1) cells, with the overproducing plasmid harboring the MHR1 gene (pYESTrp1MHR1) or without the ORF (pYESTrp1), were grown at 34°C in SD medium supplemented with all of the required amino acids, except tryptophan (lanes 2–8), from 1.0 × 105 cells/ml to 5.0 × 107 cells/ml. The cells were transferred to raffinose medium containing 2% galactose for the induction of the GAL1 promoter, and aliquots were obtained at the various times indicated in the figure during the incubation at 34°C. Whole cellular DNA was isolated and analyzed by one-dimensional electrophoresis without restriction endonuclease-treatment. (A) Gel stained with ethidium bromide. (B) Signals from the mt-pMK2 DNA, obtained by Southern hybridization by using the [32P]pMK2 DNA probe. CC, closed circular monomer; NC and m (region), nicked circular monomer; c (region), concatemers. Lane 1, 5-kb ladder as a size marker. Lane 9, the isolated plasmid pMK2 DNA. (C) Quantification of the signals in B. Based on the Southern hybridization experiment, the 32P signals of the pMK2 DNA probe from the areas indicated in B (m, circular monomers; c, concatemers) were plotted. ▪, □ (squares), concatemeric mtDNA; ⋄, ⋄ (diamonds), circular monomeric mtDNA. Closed symbols, the mhr1-1 cells containing the MHR1 expression plasmid; open symbols, the mhr1-1 cells containing the vector without MHR1. The net signals for circular monomers were corrected as described in Figure 2E. The experiment was performed twice to confirm that the results were reproducible. A single experimental result is indicated. (D) The proteins were extracted from the sampled cells (∼2 × 105) by the use of a yeast protein kit (Zymo Research) and were subjected to immunoblotting. Both Mhr1p and mhr1-1p in the extracts were detected with the antiserum against Mhr1p. The amounts of mitochondrial proteins are indicated relative to the amount of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein, porin, detected by its antiserum.

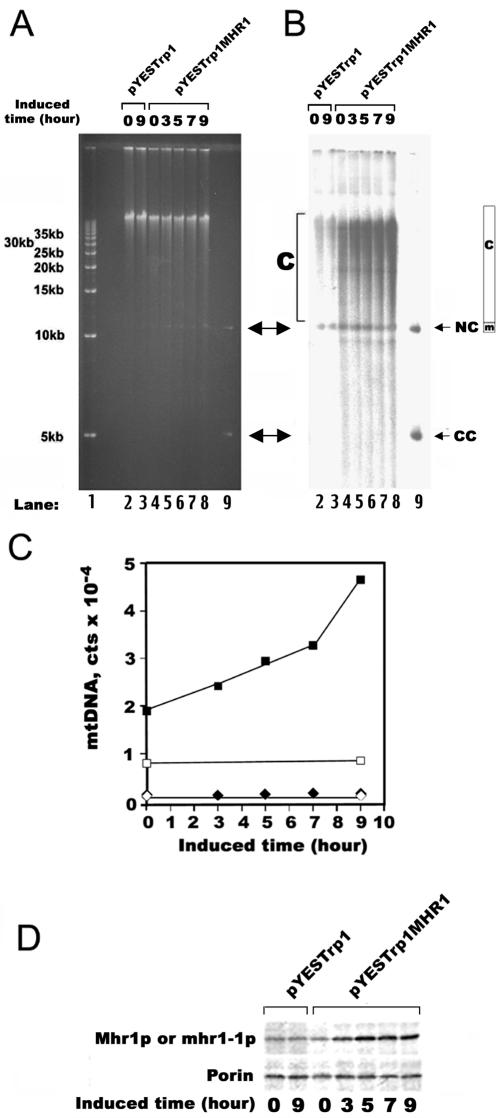

Figure 5.

The pattern of mtDNA labeling in cells arrested at G1 and the fate of the labeled mtDNA in dividing (budding) cells after the release of the G1-arrest. (A) Outline of the experiment. Nascent (newly synthesized) mt-pMK2 DNA, in AFS98-pMK2 cells arrested at G1 by α-factor, was specifically labeled by [14C]thymidine for 8 h at 30°C. Then, the radioactive thymidine was removed, excess unlabeled thymidine (0.5 mg/ml) was added, and the incubation was continued for 1 h. After the α-factor was removed to release the G1 arrest, the cells were allowed to grow synchronously at 30°C for 1.5 h in YPD medium. The cells were collected, and mother cells and buds were separated. After the separation of mother cells and buds in each preparation, we confirmed by microscopic observation that the buds were enriched to >85% of the total cells. (B) Gel profile by staining with ethidium bromide. DNA was prepared from whole cells, mother cells, and buds, separately (lanes 4–9) and was analyzed for circular monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA. For the analyses for total mt-pMK2 DNA as linear monomers, to avoid possible overlap of the 14C incorporated in nuclear DNA after the release of the G1-arrest (see lanes 8 and 14 in C: dividing ρ0 cells), an aliquot of each DNA sample was treated with the restriction endonuclease SalI, which cleaves mt-pMK2 DNA at a single site (lanes 10–15; Whole DNA/SalI). The DNA samples were electrophoresed through a 0.5% agarose gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide. Lane 1, 5-kb ladder as a size marker. Lane 2, 14C-labeled pMK2 DNA, from E. coli, digested with SalI. Lane 3, 14C-labeled pMK2 DNA, from E. coli. (C) Profile of 14C-labeled DNA. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and the 14C from only the area of the band of pMK2-DNA monomers in the gel was detected and quantified. (D) Profile of mtDNA detected by a [32P] pMK2 DNA-probe. To estimate the amount of monomers of mt-pMK2 DNA, the gel was subjected to Southern hybridization by using the [32P] pMK2 DNA-probe, and the amount of 32P within the same area used in the measurements for 14C was quantified. (E) Relative 14C-densities in mtDNA. The net 14C signal and the 32P signal of circular monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA in cells (or buds), in lanes 4 through 7 of the gels shown in C and D, respectively, were calculated with the correction described in Figure 2E. The net 14C signals and 32P signals of the total mt-pMK2 DNA (i.e., circular monomers plus concatemers in cells, measured as SalI-produced linear monomers) are the gross 14C signals and 32P signals, respectively, from linear monomers of endonuclease SalI-treated mt-pMK2 DNA in lanes 10 through 15 (in C for 14C and D for 32P) minus the gross 14C signals and 32P signals, respectively, from the corresponding gel areas for the DNA of p0 cells (lanes 14 and 15) as the background. The 14C density in each DNA species was calculated by dividing the net 14C signals by the net 32P signals. Note that the linear monomers are the major species of endonuclease SalI-treated mt-pMK2 DNA, and the other minor products (see lane 4 of Figure 2B) were ignored to avoid the overlap of the 14C signals from nuclear DNA (see lane 14 in Figure 5B), assuming the 14C density is homogeneous throughout the concatemers. As for raw data and calculations, see the Supplementary Table 1. Note that in these experimental conditions, circular monomers and linear monomers were not well separated, and were not distinguished when counting the signals. The relative values of the 14C density of each DNA species to the total mtDNA in whole growing cells (grown for 1.5 h; black bar) were plotted. Gray bars, total mt-pMK2 DNA; open bars, circular monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA. Each bar indicates the average of two independent experiments.

Analyses of ρ+ mtDNA by Pulsed Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

The W303a/pYESMHR1 and W303a/pYES2 strains were each grown at 30°C in raffinose medium, consisting of 2% raffinose, 0.7% yeast nitrogen base, and supplementary amino acids, from 1 × 105 to ∼1 × 107 cells/ml. Then, the cells were transferred to GalSR medium consisting of 2% galactose, 2% raffinose, 0.7% yeast nitrogen base, and supplementary amino acids and were cultivated at 30°C for 9 h to induce the MHR1 gene expression. Total cellular DNA for PFGE was prepared according to a published procedure (Jacobs et al., 1996).

Labeling of Nascent mtDNA, Separation of Buds and Mother Cells, Preparation of DNA from Buds and Mother Cells, and Detection of the Labeled mtDNA

AFS98-pMK2 (MHR1) cells were grown in YPGly medium to log phase at 30°C, from 1 × 105 to ∼1 × 107 cells/ml. The cells were then treated with 15 μg/ml α-factor. The nascent mt-pMK2 DNA in the α-factor–arrested G1 cells was labeled by [methyl-14C]thymidine (1.85 GBq/mmol; Amersham Biosciences) at 27.8 MBq/ml, in labeling medium containing 15 μg/ml α-factor, 5 mg/ml sulfanilamide (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 μg/ml amethopterin (Sigma-Aldrich), as described previously (Nunnari et al., 1997). After the removal of [methyl-14C]thymidine, the G1-arrested cells were cultivated with 0.5 mg/ml thymidine in the presence of α-factor for 1 h and then the thymidine and α-factor were removed by washing the cells with YPD medium. The cells were incubated at 30°C for 1.5 h with shaking in YPD medium to allow budding.

To compare the amount of 14C-labeled nascent mt-pMK2 DNA in the buds and mother cells, the buds were separated from the mother cells. The budding cells were suspended in KPSE buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM potassium phosphate, 50 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and treated with zymolyase-100T (Seikagaku America, Rockville, MD) at 84.8 U/ml for 30 min. Then, the zymolyasetreated cells were washed with KPSE and resuspended in KPSE on ice. The suspension was applied to a sucrose gradient formed in a 50-ml Falcon tube (30 mm in depth × 115 mm in length) with 5 ml each of 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 40% sucrose. Each sucrose fraction was prepared by the dilution of 40% sucrose in KPE buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate, 50 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) with the same buffer. The gradient was centrifuged at 150 × g for 5 min at 23°C. The buds and mother cells were enriched at the 15 and 25% fraction, respectively. Each fraction was collected, diluted threefold with KPSE buffer, and then centrifuged at 1400 × g for 5 min. The collected bud- and mother cell-fractions were suspended in KPSE and fractionated on the sucrose gradient again. Through microscopic observation, we confirmed that the buds were enriched to >85% of the total cells in the preparation (Ling and Shibata, 2002), after this fractionation was repeated three times.

Whole cellular DNA, prepared from the separated buds, mother cells, or whole cells, was separated by standard gel electrophoresis, except the running time was shortened to 16 h. Two series of electrophoretic fractionations were carried out, under the same set of conditions: one for the quantification of the 14C-labeled pMK2 DNA species, and the other for the measurement of the amount of pMK2 DNA species by Southern hybridization. The 14C-labeled mt-pMK2 DNA in the dried gel after electrophoresis was analyzed with a Fuji BAS2000 image analyzer, as described previously for the D-loop assay (Ling and Shibata, 2002). To quantify the amounts of mt-pMK2 DNA species, the DNA in the gel was transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane in 10× SSC by capillary transfer, detected by Southern hybridization by using 32P-labeled pUC119 to probe for pMK2 DNA, and analyzed with a Fuji BAS2000 image analyzer.

RESULTS

Genetic Segregation of Mitochondrial Alleles and Physical Segregation of mtDNA for Homoplasmy To identify the genes required for homoplasmy, we developed two assays relying on independent principles to measure the fraction of homoplasmic cells and heteroplasmic cells in a liquid culture sample: a genetic assay and a physical assay.

The genetic assay relies on the fact that each heteroplasmic cell forms a mixed colony consisting of various homoplasmic cells with a different set of mitochondrial alleles. On the other hand, each homoplasmic cell forms a homogeneous colony consisting of a single type of homoplasmic cell, with one or the other parental mtDNA or a single type of recombinant mtDNA. The details of the genetic assay are described in the MATERIALS AND METHODS (Figure 1A). Just after the mating, 10% of the cells are homoplasmic, and the fraction of homoplasmic cells increases to 70–80% within the first six to seven generations of growth at 30°C (Figure 1B, a and b). The apparent rate of increase in the fraction of homoplasmic cells slows down after the fraction exceeds 70–80% (Figure 1B). For an aged culture, this genetic assay is affected by the generation of cells with ChlR-OliR recombinant mtDNA (class 5), because the genetic assay used in this study does not discriminate between colonies derived from homoplasmic cells with ChlR-OliR recombinant mtDNA (class 5) and those derived from heteroplasmic cells containing cells with ChlR-OliR recombinant mtDNA (class 1′; the recombinant mtDNA arises in heteroplasmic cells during colony formation; see table in Figure 1A). Actually, we previously reported that after a prolonged incubation, the intergenic recombination between unlinked mitochondrial markers was 13–18%, irrespective of the presence or absence of functional MHR1 (Ling et al., 1995). Thus, the apparent fraction of homoplasmic cells obtained by the genetic assay never extends beyond 80–90%. However, because the total amount of pure and mixed colonies containing ChlR-OliR cells was less than or equal to 1–2% in younger generations (up to five generations), the fraction of homoplasmic cells with ChlR-OliR mtDNA can be ignored for the purposes of the present study, in which we examined the effects of Mhr1p activity mainly by the initial increase in the fraction of homoplasmic cells.

It is possible that the homoplasmy detected by a genetic assay is not due to homoplasmy at the DNA level, but rather to an epigenetic effect, such as the silencing of an allele at each mitochondrial locus. Therefore, we developed a physical assay for the segregation of mitochondrial alleles. The physical assay relies on the DNA sequence polymorphism at the ω locus on mtDNA, i.e., ω+ is the 21S rRNA gene split by the ω intron of ∼1.1 kbp, and ω- is the 21S rRNA allele without the intron (Dujon, 1981). We used another intronless allele with the ω-endonuclease (I-SceI)-resistant mutation (ωn), which is not converted to ω+ in ω+/ωn heteroplasmic cells and allows the stable maintenance of both alleles in heteroplasmic cells (Dujon, 1981). The mtDNA at the ω locus was amplified by DNA PCR on templates prepared from randomly selected colonies originating from cells that had grown for four generations after the mating of ω+ and ωn cells. Among the 32 cases tested, only the ω+ or ωn DNA fragment was detected in all of the colonies derived from cells that had been identified as homoplasmic by the genetic assay, whereas both the ω+ and ωn DNA fragments were detected in all of the cells genetically identified as being heteroplasmic (Figure 1C).

Among the three colonies that contained cells with ChlR-OliR recombinant mitochondria and were not tested for homoplasmy by the genetic assay, the PCR assay revealed that two were homoplasmic (Figure 1C, lanes 6 and 7) and one was heteroplasmic (Figure 1C, lane 37).

Thus, with our test using the MHR1 cells, the genetic and physical assays both gave the same results. Therefore, it is likely that homoplasmy is not an epigenetic event, but is the physical segregation of heteroallelic mtDNA. Homoplasmy was originally defined by the genetic segregation of mitochondrial alleles, and thus, we used the genetic assay to test the effects of mutations and overexpression in the following experiments.

The Effects of Mhr1p Overproduction on the Vegetative Segregation of Mitochondrial Alleles to Generate Homoplasmic Cells

The mhr1-1 cells exhibit temperature-stimulated defects, and during cultivation at 37°C, all of the cells become vegetative petite (ρ- or ρ0; Ling et al., 1995). The petite cells do not express mtDNA genes because of the absence of mitochondrial protein synthesis (Dujon, 1981), and thus, the production of petite cells disturbs the genetic assay for homoplasmy. Therefore, we first tested the effects of Mhr1p overproduction.

Heteroplasmic zygotes were cultured at 30°C in liquid medium containing galactose (GalSR) for the induction of the GAL1 promoter, which controls MHR1 expression on the pYESTrp1MHR1 plasmid. No petite cells were produced during the cultivation under these conditions. The rate of increase in the fraction of homoplasmic zygotic cells, after mating cells that overproduced Mhr1p, was significantly faster (∼2.5 fold) than that observed after mating cells that lacked the Mhr1p-overproducing plasmid (Figure 1B, a). As control experiments, ABF2 (a mitochondrial nucleoid DNA-binding protein; MacAlpine et al., 1998) or CCE1 (a mitochondrial recombination-junction resolving enzyme; Kleff et al., 1992) was overexpressed alone. We did not detect any change in the rate at which homoplasmy was attained in these cases (Figure 1B, b), showing that the accelerated vegetative segregation to homoplasmy mediated by the overproduction of Mhr1p is not simply a general property of the overproduction of proteins that act on DNA.

The mhr1-1 Mutation Delays the Vegetative Segregation of Mitochondrial Alleles

It is possible that the enhanced vegetative segregation of mitochondrial alleles does not reflect the in vivo role of Mhr1p and is an event induced only by the overproduction of Mhr1p. If the Mhr1p-dependent vegetative segregation were the major pathway to generate homoplasmic cells, then the defective mutation mhr1-1 should cause a delay in vegetative segregation. Thus, we examined the effects of the mhr1-1 mutation on vegetative segregation. In the absence of functional Mhr1p (e.g., mhr1-1 cells cultured at 37°C), all of the cells in a culture become vegetative petites (Ling et al., 1995). To avoid the disturbance by the petite production, we chose 34°C as the experimental temperature, after confirming the absence of respiration-deficient cells at this temperature, even in the mhr1-1/mhr1-1 diploid culture. We detected no difference between diploids derived from MHR1 × MHR1 crosses and those derived from MHR1 × mhr1-1 crosses (our unpublished data), as expected from the dominance of MHR1 over mhr1-1 (Ling et al., 1995). We found a clear reduction in the initial rate of appearance (about one-half) of homoplasmic cells in mhr1-1/mhr1-1 diploid cultures, compared with MHR1/mhr1-1 diploid cultures (Figure 1B, c). This delay is not a consequence of any mitochondrial architectural changes by the mutation, because the mhr1-1 mutation does not alter mitochondrial morphology (our unpublished data). A null mutation of cce1 (cce1::LEU2 × cce1::LEU2) did not significantly change the initial rate of the return to homoplasmy (our unpublished data). Cells with a null mutation of abf2 produced respiration-deficient cells during the cultivation and were not examined.

A control experiment excluded the possibilities that the homoplasmy is attained by the selective or faster growth of diploid cells containing homoplasmic mitochondria derived from only one of either parent and that the activity of Mhr1p changes the selectivity, i.e., at the beginning of the incubation at 34°C in SD medium, homoplasmic cells represented 20% of the cell population, and within 4.5 generations, 72% of the cells in the culture became homoplasmic (the cultivation shown in Figure 1B, c). If the homoplasmic cells grew at least twice as fast as the heteroplasmic cells, then this could be explained, and if so, a lag or a sigmoid curve would be apparent when the logarithms of the numbers of cells are plotted against the culture time. However, we did not detect such a lag or change in the growth rate of MHR1/mhr1-1 or mhr1-1/mhr1-1 cells at either 30 or 34°C; the cells grew exponentially for at least six generations.

Thus, these genetic studies revealed that the overexpression of MHR1 accelerates vegetative segregation and that the mhr1-1 mutation causes a delay in this process. These results indicate that Mhr1p plays an active and major role in the vegetative segregation of mitochondrial alleles in heteroplasmic cells to generate homoplasmic cells.

The fraction of homoplasmic cells with ChlS-OliS recombinant mitochondria (class 4; see MATERIALS AND METHODS) was 1.7 ± 0.4% of the entire culture, in which 73% of the cells were homoplasmic (at 4.5 generations, in the experiments shown in Figure 1B). This excludes the hypothesis that gene conversion at each heteroallelic locus is the major mechanism for generating homoplasmic cells, as explained in DISCUSSION.

The Formation of Concatemeric mtDNA Is Suppressed by mhr1-1 and Is Enhanced by the Overproduction of Wild-Type Mhr1p

Our previous studies suggested that the concatemers, formed by either the Mhr1p-dependent major pathway or the Cce1p-dependent minor pathway, are the essential intermediates for the partitioning of mtDNA into buds (see INTRODUCTION: Ling and Shibata, 2002). The transmission of concatemers consisting of a clone of copies derived from a few selected template mtDNAs would stimulate the generation of homoplasmic progeny cells; therefore, we examined the effects of mhr1-1 and the overexpression of Mhr1p on the formation of concatemers. The mtDNA of S. cerevisiae is ∼80 kbp, which requires PFGE for its analysis. Like concatemers, circular mtDNA (even monomers) does not enter the gel in PFGE (Bendich, 1996), and this technical limitation could obscure the effects of a mutation on the concatemer formation. In fact, when we compared the size distribution of the wild-type mtDNA (ρ+ mtDNA) between MHR1 cells and mhr1-1 cells at 34°C, mhr1-1 caused an increase in the relative amount of monomeric mtDNA to mtDNA that did not enter the gel, but the effects of mhr1-1 were smaller than those expected from the previous suggestion (Supplementary Figure 3 in Ling and Shibata, 2002). Thus, we reexamined the effects of mhr1-1 on the size distribution of whole cell mtDNA, by using conventional gel electrophoresis and cells containing mtDNA with a small unit size (mt-pMK2 DNA, 9.5 kbp; vegetative petite (ρ-) phenotype; Thorsness and Fox, 1990). We confirmed that even in a heteroallelic cross of (nonhypersuppressive) ρ- cells, in the presence of active Mhr1p, ∼90% of the cells in the culture at 34°C became homoplasmic with either type of parental ρ- mtDNA after approximately six generations of cell growth, but in the absence of active Mhr1p, >40% of the cells remained in a heteroplasmic state for the same number of generations, indicating that Mhr1p functions in the establishment of homoplasmy, even in ρ- cells.

Whole cellular DNA was isolated and was analyzed by one-dimensional and two-dimensional electrophoresis. To reduce the overlap with the nuclear chromosomal DNA on the gel, the whole cellular DNA was treated with the restriction endonuclease ClaI, which has no cleavage site in pMK2 DNA (compare lanes 2 and 3 with lanes 4 and 5 in Figure 2A). The signals detected by Southern hybridization with the [32P]pMK2 DNA probe are solely derived from mtpMK2 DNA, because no signal was detected when whole DNA isolated from ρ0 (mtDNA-less) cells was examined (Figure 2, A and B, lanes 8 and 9; quantification, E).

The majority of the mt-pMK2 DNA from the MHR1 cells migrates as a linear form with variable lengths, as shown by the one-dimensional (Figure 2B, lane 2) and two-dimensional electrophoresis profiles (Figure 2D), apparently centered between 35 and 70 kb (tetramers to heptamers; Figure 2B, lane 2). The cleavage of the mt-pMK2 DNA from the MHR1 cells by the restriction endonuclease SalI, which cuts the mt-pMK2 DNA at one site, produced DNA of the unit size of pMK2 as the major product (Figure 2B, lane 4), confirming the previous observation that the concatemer is the major species of mt-pMK2 DNA. After the cleavage of mt-pMK2 DNA by SalI, some pMK2 DNA was detected as fragments larger than the unit size (Figure 2B, lane 4). This is likely to reflect the fact that mtDNA contains single-stranded regions and recombination junctions, which render the DNA resistant to restriction endonuclease cleavage (Han and Stachow, 1994; MacAlpine et al., 1998).

The two-dimensional (Figure 2D) gel profiles suggest that the size distribution of the concatemers is continuous, with no sign of bands or dots with unique sizes. Such concatemers with a continuous size distribution are the expected products of rolling circle replication, rather than those of crossing over. The latter pathway would produce concatemers with multiples of the unit size.

When DNA was isolated from the mhr1-1 cells grown at a sublethal temperature, 34°C, the amount of concatemeric mt-pMK2 DNA significantly decreased relative to its circular monomeric (nicked circular) form (Figure 2B, lane 3 versus lane 2). The amounts of whole mt-pMK2 DNA in mhr1-1 cells seemed to decrease (Figure 2, A versus B; E and F), as we reported previously for ρ+ mtDNA (Ling et al., 1995). The signal quantifications of the one-dimensional (Figure 2E) and two-dimensional (Figure 2F) gel profiles indicated that the ratio of concatemers to circular monomers was decreased 3.5-fold, from 27.2 ± 1.8 in the MHR1 cells to 7.8 ± 0.5 (two independent experiments using one-dimensional gels and two-independent experiments using two dimensional gels). These results indicate that the concatemer formation is significantly suppressed by the mhr1-1 mutation.

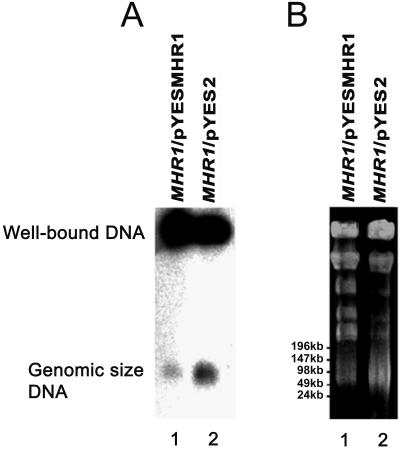

We examined the effects of Mhr1p overproduction in mhr1-1 cells. AFS984a-pMK2 (mhr1-1) cells with the plasmid overproducing the MHR1 gene product (pYESTrp1MHR1) or without the ORF (pYESTrp1) were grown at 34°C in SD medium. Then, the cells were transferred to medium containing galactose for the induction of the GAL1 promoter. Whole cellular DNA was isolated from cells grown in the galactose-containing medium and was analyzed by one-dimensional electrophoresis. We tried to load the same amount of whole cellular DNA into the wells (lanes 2 through 8 in Figure 3A). Even without the induction of the GAL1 promoter, the concatemer formation resumed with the introduction of the MHR1-overexpressing plasmid in the mhr1-1 cells (Figure 3B, lane 4 versus lane 2). When the production of Mhr1p was induced by galactose (Figure 3D), the amounts of concatemeric mt-pMK2 DNA increased with time during the induction, with only a slight increase, if any, in the amount of circular monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA (Figure 3B; quantification, Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained for the ρ+ mtDNA, in a comparison between the normal MHR1 cells and the Mhr1p-overproducing cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

PFGE profiles of ρ+ mtDNA in MHR1 cells that overproduce Mhr1p. The MHR1 cells (W303a/pYES2) with only the vector pYES2, and the MHR1 cells (W303a/pYESMHR1) with the plasmid DNA bearing MHR1 inserted under the control of the GAL promoter (pYESMHR1) were cultured in galactose-containing medium (YPGal) at 30°C to mid-logarithmic phase (from 1 × 105 to ∼5 × 106 cells/ml). Then, the preparation of the total cellular DNA for PFGE and the PFGE were performed, as described in Ling and Shibata (2002). (A) The detection of signals from mtDNA, by using 32P-labeled purified r+ mtDNA as a probe. (B) The detection of DNA under UV-light after ethidium bromide staining. λ ladder DNA (concatemers) and λ DNA digested with HindIII were used as size markers. Note that the relative intensities of the genomic size mtDNA (∼80 kbp) to the well-bound DNA were weaker in the Mhr1p-overproducing cells compared with the normal MHR1 cells.

These analyses clearly show that the Mhr1p activity positively correlates with the relative amounts of concatemeric to circular monomeric mtDNA (mt-pMK2 DNA and ρ+ DNA). Thus, Mhr1p plays a major role in the formation of concatemeric mtDNA, and the rate of the vegetative segregation of mitochondrial alleles positively correlates with the relative abundance of concatemeric mtDNA.

Concatemers Are the Immediate Products of mtDNA Replication and Are Precursors of Circular Monomers in Buds

We carried out labeling and chasing experiments to determine whether concatemers are the immediate products of replication and/or the intermediate for the partitioning of mtDNA into buds. As illustrated in Figure 5A, nascent mtpMK2 DNA was specifically labeled with [14C]thymidine in cells arrested at G1 by α-factor (thus, the nuclear chromosomal DNA was not labeled; Figure 5C, lane 7 versus lane 9 [ρ0]), and after the removal of the labeling agent, the arrest was released to allow the cells to grow synchronously, to chase the fate of the [14C]mtDNA. It is known in bacteria that concatemeric DNA is formed by either of recombination-dependent pathways, directly by rolling circle replication or through crossing over of circular monomers (Ling and Shibata, 2002; DISCUSSION). If circular monomers are the immediate products of replication from which concatemers are formed, then the 14C would be preferentially incorporated into circular monomers. If concatemers are the immediate products of rolling circle replication, then the 14C would be preferentially incorporated into concatemers. Because the amount of concatemeric mtDNA is generally much higher than that of circular monomers in whole cells and mother cells, and circular monomeric mtDNA is the major species in the growing buds of dividing cells, the experimental results must be evaluated by using the 14C density, rather than the absolute amounts of 14C incorporated into each mtDNA species. The 14C density is the amount of 14C per unit amount of mt-pMK2 DNA, which was estimated by Southern hybridization with a [32P]pMK2 DNA probe.

We isolated DNA from whole cells sampled just before the release and after 1.5 h of growth and from separated mother cells and buds of dividing cells sampled after 1.5 h of growth. Then, the DNA samples were divided into two aliquots: one for the analysis of circular monomeric mtpMK2 DNA and the other for the analysis of total mt-pMK2 DNA (i.e., monomers plus concatemers). For the analysis of total mt-pMK2 DNA as (linear) monomers, to avoid possible overlap of the 14C incorporated in nuclear DNA after the release of the G1 arrest, the DNA samples were treated with the restriction endonuclease SalI, which cuts the mt-pMK2 DNA at one site (Figure 5C, lanes 8 and 14). Then, the 14C incorporation (Figure 5C) into mt-pMK2 DNA (and its amount, determined by Southern hybridization by using a [32P]pMK2 DNA probe; Figure 5D) was analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The 14C density in the circular monomeric and total mt-pMK2 DNA is calculated by dividing the 14C signal in the band for monomeric pMK2 DNA, without and with SalI-treatment, respectively, by the 32P signal in the same band (see the Supplementary Table 1, as for an example of the calculation). In Figure 5E, the 14C densities of mt-pMK2 DNA samples from G1-arrested or dividing cells, relative to that of the total mt-pMK2 DNA from dividing cells, were calculated, and the average values from two independent experiments were plotted.

In cells arrested at G1, most of the [14C]thymidine is preferentially incorporated into concatemers, because the circular monomers were labeled to a much lower extent than the total DNA. Thus, these results exclude the possibilities in which the immediate products of mtDNA replication are circular monomers, and consequently indicate that concatemers are the immediate products of mtDNA replication.

After 1.5 h of growth and budding, the 14C density of the circular monomers remained much smaller as compared with that of the total mt-pMK2 DNA in mother cells, but unlike the situation in the mother cells, the 14C density of the circular monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA in the buds was much higher than that of the circular monomers in the mother cells and is similar to that of the total mt-pMK2 DNA in mother cells or whole cells.

This result is most simply explained by a model in which the concatemeric mtDNA formed in mother cells is processed into circular monomers upon partitioning into buds. However, before considering this explanation as a conclusion, we needed to evaluate the observed residual incorporation of [14C]thymidine into the chromosome from the intracellular DNA precursor pool, after the removal of the labeling agent and the initiation of cell growth, i.e., 14C-labeled large chromosomal DNA species (not hybridized to the mt-pMK2 DNA-probe; lane 8 in Figure 5, C and D) were detected in the mtDNA-devoid (ρ0) dividing cells (but not in ρ0 cells at G1; compare lane 8 with lane 9 in Figure 5C). This residual incorporation could not be avoided, even if we included a step in which the cells were incubated in the presence of α-factor and excess unlabeled thymidine for 1 h after the removal of the [14C]thymidine, and before the release of the arrest at G1. The incorporation of 14C into chromosomal DNA could affect the calculation of the signals from [14C]mt-pMK2 DNA, but in the control sample devoid of mtDNA (DNA from ρ0 cells), the signals derived from the chromosomal DNA at the position for the band of monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA (Figure 5C; in lane 8 for the control of monomeric mtDNA in each sample, and lane 14 for the control of SalI-cleaved total mtDNA in each sample) were very small (the signals in lane 14 were <3% of the 14C signals derived from monomers obtained from SalI-cleaved mt-pMK2 DNA in lane 12). Thus, the possible signals derived from the chromosomal DNA can be ignored in the estimations of 14C incorporation into monomeric mt-pMK2 DNA and total mt-pMK2 DNA.

DISCUSSION

The overexpression of MHR1 caused an acceleration in the generation of homoplasmic cells, whereas a defective mutation (mhr1-1) of the gene delayed the generation of homoplasmic cells, and these effects were observed only with Mhr1p, among the three mtDNA interacting proteins tested (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that Mhr1p plays an important and major role in the generation of homoplasmic cells.

Hypotheses for the Mechanism of Homoplasmy

Possible mechanisms for the segregation are 1) polar gene conversion at each heteroallelic locus; 2) selection for cells with a particular mitochondrial genotype; 3) intracellular selection for mtDNA with a particular genotype; 4) transmission of a few (approximately three; see INTRODUCTION) copies of mtDNA copies into daughter cells; 5) specific replication of a few selected mtDNA templates; and 6) selective transmission of a few clones of mtDNA (Figure 6; Backer and Birky, 1985).

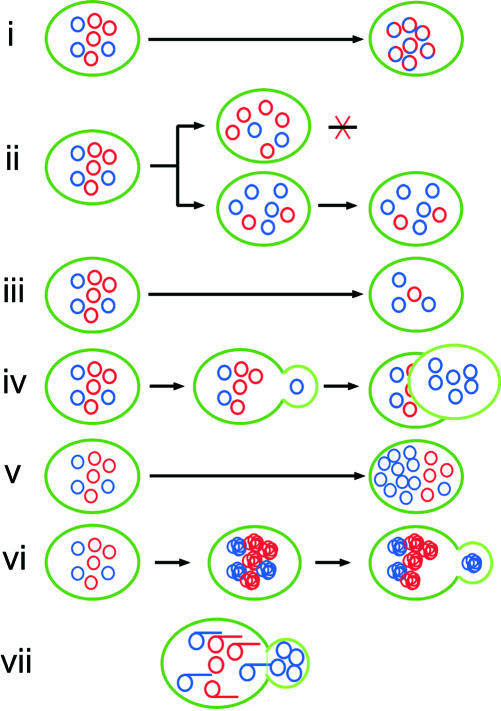

Figure 6.

Hypothetical mechanisms for the generation of homoplasmic cells from heteroplasmic cells. i) Polar gene conversion at each heterozygous locus. This results in cells with recombinant mtDNA at 50%, if alleles at more than two loci are examined; ii) selective growth of cells with a particular mitochondrial genotype; iii) intracellular selection for mtDNA with a particular genotype: mtDNA with a particular genotype acquires a replication advantage, such as hypersuppressive ρ- mtDNA; iv) the transmission of a few (approximately three; see INTRODUCTION) copies of mtDNA copies into daughter cells; v) specific replication of a few selected mtDNA templates; vi) selective transmission of a few clones of (physically connected) mtDNA; vii) our model supported by the current study: a few clones of mtDNAs replicated on common templates are selectively transmitted into buds as concatemers formed by rolling circle replication (and are processed into circular monomers). Red circles and blue circles represent mtDNA units with different sets of alleles. Except for i, homoplasmic cells with blue mtDNA will be generated. Overlapped circles represent clones of (physically connected) mtDNA replicated on a common template.

The absence of homoplasmic cells with recombinant mtDNA at an early stage of segregation of mitochondrial alleles (see RESULTS) excludes the possibility that the independent segregation of each mitochondrial allele by gene conversion (possibility 1) is a major mechanism for homoplasmy, because the random segregation at unlinked loci (for Chl- and Oli-sensitivities) should result in the generation of homoplasmic cells with ChlS-OliS or ChlR-OliR recombinant mitochondria at a frequency of 50%.

The selection for cells with particular mitochondrial genetic markers (possibility 2) is very unlikely, because homoplasmic cells are segregated even in the absence of selective pressure (e.g., this study). The intracellular selection for mtDNA with a particular genotype (possibility 3) is very unlikely, because in the case described in this study, the two parental mtDNAs differ by only two base pairs in antibiotic resistance genes and by the presence or absence of the inactive ens2 gene, and these differences are unlikely to give a replicative advantage to one type of mtDNA over the other. In addition, neither type of selection is consistent with the fact that the ratio of cells with an allele derived from the α parent to those containing the allele derived from the a parent, among the homoplasmic cell populations, remained constant for at least the first eight generations, during which most cells became homoplasmic, irrespective of the locus (Chl or Oli) following the “input ratio” hypothesis (Dujon, 1981), and did so in both MHR1/mhr1-1 cultures and mhr1-1/mhr1-1 cultures.

The transmission of a few mtDNA-copies (possibility 4) is inconsistent with our previous observation on the transmission of a detectable level of mtDNA labeled before the start of cell division, i.e., in dividing cells with mtDNA labeled by bromodeoxyuridine during the preceding G1 arrest, at least five to 10 mitochondrial nucleoids were detected by a fluorescein-conjugated antibody against bromodeoxyuridine-containing DNA (Figure 1A in Ling and Shibata, 2002). In addition, it is unlikely that each mitochondrial nucleoid detected in the above-mentioned experiments contains only a single copy of mtDNA.

Biological Functions of Mhr1p

Therefore, we discuss the functions of Mhr1p (a protein promoting homologous pairing for homologous recombination; Ling and Shibata, 2002) considering possibilities 5 and 6. In the current study, we showed that the abundance of mtDNA concatemers depends on the level of Mhr1p activity (Figures 2, 3, 4). Homologous pairing protein-dependent mechanisms for concatemer formation include either rolling circle replication (to form concatemers directly; e.g., late phase replication dependent on the β protein in Escherichia coli phage λ) or monomer joining by crossing over (e.g., uvsX-dependent replication in E. coli phage T4). Rolling circle replication was suggested as a mechanism for the replication of mtDNA in yeasts by others (Maleszka et al., 1991; Han and Stachow, 1994; MacAlpine et al., 1998) and by ourselves (Ling and Shibata, 2002). The continuous size distribution of the mtDNA concatemers, without the significant presence of mtDNA species of discrete sizes (Figure 2D), favors rolling circle replication as the concatemer formation mechanism. As more critical evidence, our labeling experiments showed that concatemers, not monomers, are the immediate products of mtDNA replication (Figure 5). These observations exclude the concatemer formation by the crossing over of monomers and thus support a model in which mtDNA replicates predominantly by Mhr1p-dependent rolling circle replication to form concatemers.

Due to the technical limitations of pulsed field gel electrophoresis, which cannot distinguish between concatemers and circular monomers of the size of ρ+ mtDNA (unit size, ∼80 kbp; Bendich, 1996), we relied on conventional gel electrophoresis, which requires mtDNA with a sufficiently small size, i.e., ρ- mtDNA; we used ρ- mtDNA with the unit size of 9.5 kbp (mt-pMK2 DNA; Ling and Shibata, 2002). Some reports have indicated that the replication of ρ+ mtDNA and that of ρ- mtDNA are not exactly the same, in terms of their genetic requirements. Some of the differences can be explained by the absence of oxidative damage to mtDNA in cells with ρ- mtDNA, and the extensive oxidative damage to mtDNA from byproducts of oxidative respiration in mitochondria with ρ+ mtDNA (Ling et al., 2000). Even considering this fact, both still have differences in the effects of the mutations (Lockshon et al., 1995; Zelenaya-Troitskaya et al., 1998; Zuo et al., 2002). However, we believe that the mechanistic studies on the replication and partitioning of ρ- mtDNA have provided a close approximation of these mechanisms for ρ+ mtDNA, especially at our current preliminary stage of understanding, because we showed the following common features between ρ+ and ρ-: the establishment of homoplasmy from heteroplasmic zygotes depends on the activity of Mhr1p (this study); and concatemers are the major mtDNA species in mother cells, and the circular monomeric form is the major mtDNA species in buds (Ling and Shibata, 2002; this study). Although the difference in the ρ+ cells was much smaller than that expected, the relative amount of concatemeric mtDNA to circular monomeric mtDNA depended on the Mhr1p activity in the cells (Figure 2 in the supplementary data of Ling and Shibata, 2002; this study).

A null mutation of cce1 (cce1::LEU2 × cce1::LEU2) did not significantly change the rate of the return to homoplasmy (our unpublished data). Cce1p (identical to Mgt1p) was considered to play roles in the segregation of mtDNA from zygotes (Lockshon et al., 1995). Our results do not necessarily mean that CCE1 has no role in the vegetative segregation of mitochondrial alleles, i.e., the Cce1p-dependent pathway plays a relatively minor role in the partitioning (and thus, the maintenance) of ρ+ mtDNA (Ling and Shibata, 2002) and thus, even if Cce1p plays a role in mitochondrial allele segregation, it may not have been detected in the current study. In the absence of Mhr1p, all cells are ρ- or ρ0 and the genetic assay cannot be applied to test the role of Cce1p in homoplasmy under such genetic background.

A Likely Mechanism for the Generation of Homoplasmic Cells

The observed correlation between the abundance of mtDNA concatemers and the rate of the generation of homoplasmic cells (Figures 2, 3, 4 versus 1B) suggests a role of concatemer formation in homoplasmy. We demonstrated by chasing experiments that the 14C density of the circular monomeric or total mtDNA in buds was approximately similar to the total mtDNA level of the mother cells of dividing cells and to the total mtDNA in whole cells arrested at G1 (Figure 5E), supporting the hypothesis proposed in our previous study, i.e., concatemers are the obligatory intermediates for partitioning and are processed into circular monomers upon transmission from mother cells to buds (daughter cells (see INTRODUCTION; Ling and Shibata, 2002). Rolling circle replication (discussed above) followed by partitioning of mtDNA as concatemers (Figure 6, vii) is a likely mechanism for the transmission of a few clones of mtDNA copies from a common template, and fits hypothesis 6 (selective transmission of a few clones of mtDNA derived from a template mtDNA). The selective transmission of newly and selectively replicated mtDNA (included in possibility 5) does not seem to contribute to vegetative segregation as a major mechanism, because the 14C density of the total mtDNA in buds was approximately similar to the total mtDNA level of the mother cells. If the newly replicated mtDNA were selectively transmitted to buds, then the 14C density of the total mtDNA in buds would be much higher than that in mother cells.

Mammals are homoplasmic at birth, wherein homoplasmy is attained during oogenesis, and heteroplasmic animals become homoplasmic after only two to three generations (Ashley et al., 1989). Although there is an argument that the yeast mtDNA replication system diverges from that observed in humans (as an example, see Lecrenier and Foury, 2000), the possibility of mtDNA recombination in mammals has been reported recently (Thyagarajan et al., 1996; Tang et al., 2000). Thus, our findings may also have consequences for future studies of mammalian homoplasmy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter E. Thorsness and Thomas Fox (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) for yeast cells with pMK2 in the mitochondria. This study was supported in part by a grant for the “Bioarchitect Research Program” of RIKEN to F.L. and T.S. and by a grant for Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology from Japan Science and Technology Corporation to T.S.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–07–0508. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03–07–0508.

Online version of this article contains supplementary material for some tables. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

References

- Ashley, M.V., Laipis, P.J., and Hauswirth, W.W. (1989). Rapid segregation of heteroplasmic bovine mitochondria. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 7325-7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backer, J.S., and Birky, C.W., Jr. (1985). The origin of mutant cells: mechanisms by which Saccharomyces cerevisiae produces cells homoplasmic for new mitochondrial mutations. Curr. Genet. 9, 627-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert, S. (2002). R-loop-dependent rolling-circle replication and a new model for DNA concatemer resolution by mitochondrial plasmid mp1. EMBO J. 21, 3128-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendich, A.J. (1996). Structural analysis of mitochondrial DNA molecules from fungi and plants using moving pictures and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Mol. Biol. 255, 564-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birky, C.W., Jr. (1978). Transmission genetics of mitochondria and chloroplasts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 12, 471-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.M., George, M., Jr., and Wilson, A.C. (1979). Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 1967-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujon, B. (1981). Mitochondrial genetics and function. In: The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces: Life Cycle and Inheritance, eds. J. N. Strathern, E. W. Jones, and J. R. Broach, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 505-635.

- Han, Z., and Stachow, C. (1994). Analysis of Schizosaccharomyces pombe mitochondrial DNA replication by two dimensional gel electrophoresis. Chromosoma 103, 162-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, R. (1964). A mechanism for gene conversion in fungi. Genet. Res. 5, 282-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, M.A., Payne, S.R., and Bendich, A.J. (1996). Moving pictures and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis show only linear mitochondrial DNA molecules from yeasts with linear-mapping and circular-mapping mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet. 30, 3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleff, S., Kemper, B., and Sternberg, R. (1992). Identification and characterization of yeast mutants and the gene for a cruciform cutting endonuclease. EMBO J. 11, 699-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrenier, N., and Foury, F. (2000). New features of mitochondrial DNA replication system in yeast and man. Gene 246, 37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightowlers, R.N., Chinnery, P.F., Turnbull, D.M., and Howell, N. (1997). Mammalian mitochondrial genetics: heredity, heteroplasmy and disease. Trends Genet. 13, 450-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, F., Makishima, F., Morishima, N., and Shibata, T. (1995). A nuclear mutation defective in mitochondrial recombination in yeast. EMBO J. 14, 4090-4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, F., Morioka, H., Ohtsuka, E., and Shibata, T. (2000). A role for MHR1, a gene required for mitochondrial genetic recombination, in the repair of damage spontaneously introduced in yeast mtDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 4956-4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, F., and Shibata, T. (2002). Recombination-dependent mtDNA partitioning. In vivo role of Mhr1p to promote pairing of homologous DNA. EMBO J. 21, 4730-4740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockshon, D., Zweifel, S.G., Freeman-Cook, L.L., Lorimer, H.E., Brewer, B.J., and Fangman, W.L. (1995). A role for recombination junctions in the segregation of mitochondrial DNA in yeast. Cell 81, 947-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., McKenzie, A., III, Demarini, D.J., Shah, N.G., Wach, A., Brachat, A., Philippsen, P., and Pringle, J.R. (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAlpine, D.M., Perlman, P.S., and Butow, R.A. (1998). The high mobility group protein Abf2p influences the level of yeast mitochondrial DNA recombination intermediates in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6739-6743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleszka, R., Skelly, P.J., and Clark-Walker, G.D. (1991). Rolling circle replication of DNA in yeast mitochondria. EMBO J. 10, 3923-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari, J., Marshall, W.F., Straight, A., Murray, A., Sedat, J.W., and Walter, P. (1997). Mitochondrial transmission during mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is determined by mitochondrial fusion and fission and the intramitochondrial segregation of mitochondrial DNA. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 1233-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoubridge, E.A. (1998). Mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 11, 491-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y., Manfredi, G., Hirano, M., and Schon, E.A. (2000). Maintenance of human rearranged mitochondrial DNAs in long-term cultured transmitochondrial cell lines. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2349-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsness, P.E., and Fox, T.D. (1990). Escape of DNA from mitochondria to the nucleus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 346, 376-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyagarajan, B., Padua, R.A., and Campbell, C. (1996). Mammalian mitochondria possess homologous DNA recombination activity. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27536-27543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin, H., Staehelin, T., and Gordon, J. (1979). Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76, 4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenaya-Troitskaya, O., Newman, S.M., Okamoto, K., Perlman, P.S., and Butow, R.A. (1998). Functions of the high mobility group protein, Abf2p, in mitochondrial DNA segregation, recombination and copy number in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 148, 1763-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, X.M., Clark-Walker, G.D., and Chen, X.J. (2002). The mitochondrial nucleoid protein, Mgm101p, of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is involved in the maintenance of rho(+) and ori/rep-devoid petite genomes but is not required for hypersuppressive rho(-) mtDNA. Genetics 160, 1389-1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.