Abstract

Although fear and travel avoidance among anxious drivers are well documented, relatively little is known about the behavior of anxious individuals who continue to drive. Previous research has identified three broad domains of anxious driving behavior: exaggerated safety/caution behaviors, anxiety-based performance deficits, and hostile/aggressive driving behaviors. In an effort to explicate factors associated with the development of anxious driving behaviors, associations with objective accident severity, accident-related distress, and life stress history were explored among individuals reporting accident involvement (N = 317). Interactive effects of accident distress and self-reported stress history were noted across all three domains of anxious driving behavior. Examination of these effects indicates unique associations between accident distress and anxious behavior only in those reporting more severe life stress. Consistent with contemporary models of anxiety, these data suggest stress history may serve as a general vulnerability factor for development of anxious driving behavior following accident involvement.

Keywords: driving anxiety, driving behavior, life stress, motor vehicle accidents

Anxious drivers have been shown to engage in a variety of fear-related behaviors that may be considered reckless, inappropriate, or dangerous (e.g., J. Taylor, Deane, & Podd, 2007; Matthews et al., 1998). In an effort to quantify the occurrence of anxiety-related driving behaviors, Clapp et al. (2011) identified three distinct dimensions of problematic behavior - exaggerated safety/caution, anxiety-based performance deficits, and hostile/aggressive behaviors. These behaviors are believed to contribute to negative driving outcomes and poor response to anxiety-oriented treatments, but factors associated with the development of anxious driving behavior remain unexplored. Given evidence that aversive driving experiences such as traffic accidents may contribute to the development of driving anxiety in some individuals (e.g., Mayou, Simkin, & Threlfall, 1991), the current report explores the association of accident severity, accident-related distress, and general stress history on anxious driving behavior among individuals reporting a history of accident involvement.

Recent evidence suggests that driving anxiety may be more pervasive than previously recognized (J. Taylor & Deane, 2000; J. Taylor, Deane, & Podd, 2002). As a result, a number of studies have begun to specifically examine the behavior of those individuals who continue to drive despite feeling anxious (Clapp et al., in press; J. Taylor et al., 2007). Anxious driving behavior has been broadly conceptualized as an increase, decrease, or general disorganization of behavior as a consequence of anxiety during the operation of a motor vehicle (Clapp et al., 2011). Although reported fear among these individuals may not reach formal criteria for any specific diagnosis, the influence of subjective anxiety on overt driving behavior can result in negative consequences for both the driver and other motorists. To date, three general domains of anxious driving behavior have been identified.

The first domain involves exaggerated safety and/or excessively cautious behavior. Long noted within the driving anxiety literature, these behaviors (e.g., maintaining excessive distances from other motorists, driving far below the posted speed limit, reducing speed before progressing through an intersection) typically are conceptualized as a coping response, decreasing immediate anxiety by increasing perceptions of safety and control (Mayou et al., 1991; S. Taylor & Koch, 1995). Although effective in reducing immediate distress, theoretical models predict that safety/caution behaviors ultimately maintain anxious response by disrupting processes associated with natural fear extinction (Clark, 1999; Salkovskis, 1991). Unrecognized, persistence of exaggerated safety/caution behavior may negatively impact the efficacy of exposure-based interventions for those seeking assistance with driving-related anxiety. Exaggerated safety/caution behaviors also may be functionally detrimental to the extent that they violate accepted traffic norms. Ironically, attempts to increase safety may inadvertently place the driver and other motorists at increased risk.

Performance deficits represent a second domain of anxious behavior. Research from the traffic safety literature postulates that driving-related worry may interfere with immediate, task-related demands, contributing to impaired driving performance and overall reductions in safety (Matthews et al., 1998). Whereas research examining the association between nonspecific anxiety and driving performance is mixed (see J. Taylor, Deane, & Podd, 2008 for a review), functional impairment is commonly noted in studies examining the specific impact of driving-related anxiety. For example, J. Taylor et al. (2007) noted that anxious drivers committed a greater number of performance errors (e.g., using the incorrect lane; making inappropriate adjustments in speed) than did non-anxious controls during an experimenter-rated driving task. Similarly, Matthews et al. (1998) observed that reported dislike for driving was associated with reduced control and more frequent errors within a driving simulation task. Data from the self-report literature provide additional support for a unique association between driving anxiety and impaired driving performance (e.g., Kontogiannis, 2006).

Hostility and overt aggression is a third domain of anxious driving behavior. In a recent examination of the behavioral consequences of driving anxiety, Clapp et al. (in press) observed a number of anxiety-related hostile/aggressive behaviors (e.g., yelling, honking, aggressive gesturing) within three samples of college-aged drivers. Research exploring driving outcomes among Norwegian motorists also indicates that anxiety-related driving aggression is functionally detrimental (Ulleberg, 2002). Individuals identified as anxious-aggressive drivers in this research evidenced low ratings of perceived driving skill, greater endorsement of risky driving behavior, and high levels of accident involvement. General models of driving anger postulate that elevated trait anxiety may decrease the threshold for aggressive response to stressful traffic conditions (Deffenbacher, Huff, Lynch, Oetting, & Salvatore, 2000; Deffenbacher, Lynch, Filetti, Dahlen, & Oetting, 2003); however, driving-specific anxiety may be particularly relevant to the conceptualization of driving anger within a subset of the population.

Exaggerated safety/caution, performance deficit, and hostile/aggressive behaviors can be problematic, but specific factors contributing to the expression of these reactions are unclear. Consistent with early learning models of anxiety (e.g., Mowrer, 1960), aversive driving experiences such as accident involvement commonly are identified as a source of driving related fear (Ehlers, Hofmann, Herda, & Roth, 1994; Mayou et al., 1991; Munjack, 1984; J. Taylor & Deane, 1999). Evidence from this literature demonstrates that aversive driving experiences likely contribute to anxiety within a subset of individuals; however, it is also clear that the simple occurrence of an aversive event is insufficient to explain individual variability in the acquisition and maintenance of driving anxiety. Building on classic learning theories, contemporary behavioral models such as Mineka and Zinbarg’s (1994) stress-in-dynamic context model propose that contextual factors surrounding aversive, fear-related events – intensity of exposure, subjective fear, perceptions of controllability – are more relevant for conveying risk for prolonged anxiety than the simple presence of an aversive event (Craske, 1999; Mineka & Zinbarg, 1994). As predicted by these models, accident-related distress (e.g., perceptions of fear, threat, controllability) demonstrates robust associations with anxiety-related outcomes such as driving phobia and PTSD (e.g., Blanchard & Hickling, 2004; Ehlers, Mayou, & Bryant, 1998; Mayou, Bryant, & Ehlers, 2001). Indices of objective accident severity (e.g., extent of injury, vehicle damage) also demonstrate associations with anxiety-related difficulties although evidence supporting this relationship has been less consistent (e.g., Bryant & Harvey, 1996; Shalev et al., 1998). Generalization of this literature suggests that both accident-related distress and objective accident severity may contribute to anxious driving behavior among individuals reporting a history of traffic collisions.

Individual difference factors also are believed to contribute to fear acquisition (Craske, 1999; Mineka & Zinbarg, 1995). Craske (1999) notes that stressful life events may contribute to anxiety pathology, but the specific nature of this relationship remains unclear. Some evidence suggests that life stress may confer risk directly as evidenced through unique associations with anxiety-based pathology such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and PTSD (e.g., Blazer, Hughes, & George, 1987; Bremner, Southwick, Johnson, Yehuda, & Charney, 1993; Faravelli & Pallanti, 1989). Alternatively, stress history may interact with contextual factors, conferring risk by strengthening relationships between aversive experiences and subsequent fear (e.g., Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Mineka & Zinbarg, 1995). With respect to driving anxiety, direct associations with stress history have been noted among individuals reporting serious accident involvement (Blanchard & Hickling, 2004). Interactive effects of early stressors have been noted in the trauma literature (King, King, Foy, & Gudanowski, 1996), but little research has examined interactive effects of life stress within the context of driving anxiety or anxiety-related driving behaviors.

The current project examines influence of life stress history and accident-related contextual factors – objective accident severity and associated distress – on anxious driving behaviors among individuals reporting a history of traffic collisions. Hierarchical regression models were used to examine the direct and interactive associations of predictors on three domains of anxious behavior: exaggerated safety/caution, anxiety-related performance deficits, and hostile/aggressive driving behaviors. Gender effects also were explored given evidence that women endorse higher levels of driving anxiety than men (e.g., Ehlers et al., 1994; J. Taylor & Deane, 1999; J. Taylor & Paki, 2008). Within the current data, objective accident severity and accident-related distress were expected to demonstrate interactive associations with stress history across all three domains of anxious driving behavior. In keeping with contemporary models of anxiety, associations between contextual factors and anxious driving behavior were hypothesized to increase as a function of stress history.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 356 college undergraduates recruited across two universities. Students were eligible for participation if they reported involvement in at least one traffic collision and identified as a current driver (i.e., driving at least once every few months).1 No a priori assumptions were made regarding accident severity or severity of driving-related anxiety. Given that anxious driving behavior is conceptualized to exist on a continuum (ranging from mild, infrequent reactions to frequent, disruptive behavior), inclusion of a general sample of drivers was intended to capture both a range of accident severity and anxious behavior. Participants enrolled in the study provided informed consent and completed assessment measures online. All students received course credit for their participation. Complete data were obtained from approximately 90% of individuals (N = 319). Of these, two cases were identified as multivariate outliers during data screening procedures. High leverages and large residuals associated with these cases were determined to be the product of invariant responding (i.e., marking the same response for all items on a questionnaire). These cases were removed from analyses resulting in a final sample N = 317. All procedures received institutional review board approval. Information regarding sample characteristics, driving history, and accident involvement is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 317)a

| Age | 19.5 (1.8) |

| Sex (% male) | 52.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 70.3% |

| African American | 12.9% |

| Hispanic | 6.3% |

| Asian | 7.3% |

| Other | 0.9% |

| Age received license | 16.7 (0.9) |

| Attempts to complete driving exam | 1.2 (0.6) |

| Attended drivers school (% yes) | 68.1% |

| Current driving frequency | |

| once every few months | 7.9% |

| once a month | 9.1% |

| once a week | 6.6% |

| few times a week | 20.2% |

| daily | 56.2% |

| Moving violation (% yes) | 52.1% |

| Number of lifetime violations | 2.7 (2.0) |

| Number of accidents | 1.8 (1.0) |

| Time since most severe accident (mo.) | 22.7 (19.6) |

| Driving during the accident (% yes) | 58.4% |

| Involvement of alcohol or drugs (% yes) | 6.9% |

Some categories may not sum to 100% given incomplete responding

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Accident Severity

Details regarding accident involvement were collected using a modified interview developed by Blanchard and Hickling (2004). Given that approximately one half of respondents (51.7%) reported involvement in multiple traffic collisions (M = 1.8; SD = 1.0), participants were instructed to provide information on the accident perceived as “most serious/distressing.” For the index collision, ratings of participant injury, injury to others (injury ratings: 1 = no injury to 5 = severe injury), damage to the participant’s vehicle, and damage to other vehicles (damage ratings: 1 = no damage to 5 = irreparable damage) were summed to form an index of objective accident severity. Ratings of subjective fear, helplessness, danger, control, and certainty of death (each rated on a 0 –100 scale) were averaged to form an index of subjective accident distress.2 Criterion for accident severity and distress were selected based on research demonstrating associations between individual composite items and post-accident anxiety (e.g., Blanchard & Hickling, 2004; Dougall et al., 2001; Ehlers et al., 1998; Frommberger et al., 1998).

2.2.2. Stressful Life Events

Stressful life events were assessed using a screening device adapted from the Life Events Checklist (LEC; Blake et al., 1990). This measure included a series of 17 life stressors, and participants were instructed to indicate events which they had experienced directly. Psychometric examination of the LEC within college samples provides evidence of good temporal stability (average test-retest r = .82) and adequate convergence with alternative measures of stressful life events (average kappa = .55; Gray, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004). For the purposes of the current study, stress history was calculated as the sum of endorsed events, irrespective of event severity (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Reported life stress history (N = 317)a

| Event | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Death of Friend/Family | 147 | 46.4 |

| Physical Attack (under 18) | 108 | 34.1 |

| Threatened Death or Physical Harm | 74 | 23.3 |

| Natural Disaster | 66 | 20.8 |

| Threatened with a Weapon | 66 | 20.8 |

| Physical Attack (over 18) | 53 | 16.7 |

| Drowning or Near Drowning | 51 | 16.1 |

| Life Threatening Illness | 28 | 8.8 |

| Home Fire | 24 | 7.6 |

| Sexual Assault (under 18) | 24 | 7.6 |

| Seeing Someone Killed | 16 | 5.0 |

| Explosion | 11 | 3.5 |

| Machinery Accident | 9 | 2.8 |

| Sexual Assault (over 18) | 9 | 2.8 |

| Chemical Leak or Radiation | 5 | 1.6 |

| Combat | 5 | 1.6 |

| Plane Crash | 1 | 0.3 |

Stress history calculated as the sum of endorsed events (M = 2.2; SD = 1.9; Range = 0 –10)

2.2.3. Anxious Driving Behavior

Anxious driving behaviors were examined using the Driving Behavior Survey (DBS; Clapp et al., in press). DBS subscales assess three specific domains of anxious driving behavior: exaggerated safety/caution behavior, anxiety-based performance deficits, and hostile/aggressive behavior. Items pertain to the frequency of behavior in a particular domain and are rated on a 1 (never) to 7 (always) Likert scale. Scores are calculated as the mean of endorsed items with higher scores indicating greater frequency of behavior. Evidence of factorial validity, internal consistency, and convergent associations are provided by Clapp et al. (in press). Internal consistency of safety/caution, performance deficit, and hostile/aggressive subscales in the current sample were good to excellent (α = 0.90, 0.85, and 0.91 respectively). Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of anxious driving behavior, objective accident severity, subjective accident distress, and life stress history

| CAUT | PERF | ANG | Obj | Sub | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUT | - | |||||

| PERF | .34*** | - | ||||

| ANG | .29*** | .44*** | - | |||

| Obj | .08 | −.01 | .03 | - | ||

| Sub | .18*** | .09 | .09 | .34*** | - | |

| Stress | .03 | .04 | .20*** | .07 | .03 | - |

| M | 3.76 | 1.99 | 2.82 | 9.45 | 50.87 | 2.20 |

| SD | 1.32 | 0.88 | 1.36 | 3.04 | 21.45 | 1.87 |

Note: CAUT = Driving Behavior Survey (DBS) exaggerated safety/caution; PERF = DBS performance deficits; ANG = DBS hostile/aggressive behavior; Obj = objective accident severity; Sub = subjective accident distress; Stress = life stress history (number of events)

p<.001

3.0. Results

3.1. Exaggerated Safety/Caution Behavior

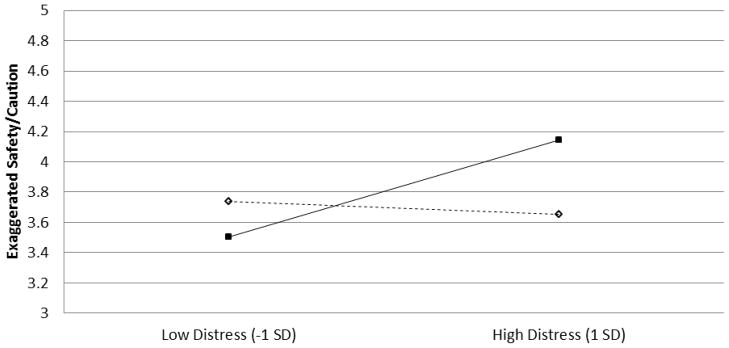

Regression analyses for all three models are presented in Table 4. With respect to exaggerated safety/caution behavior, sex effects were noted in the initial step of the analysis (adjR2 = .043) with females reporting more frequent safety/caution behavior than males (β = .214, sr2 = .046; p < .001). Direct effects included in the second step (adjR2 = .051) failed to contribute to overall predicted variance (ΔR2 = .017; p = .133) although a marginal association between accident distress and safety/caution behavior was noted (β = .118; sr2 = .011; p = .054). Interactive effects introduced in the final step of the regression (adjR2 = .065) were associated with a significant increase in model variability (ΔR2 = .020; p = .036). Consistent with hypotheses, accident distress and stress history evidenced an interactive relationship with exaggerated safety/caution behavior (β = .157; sr2 = .020; p = .010). Examination of this interaction revealed a direct relationship between accident distress and safety behavior specifically among individuals with greater stress history (β = .243; B = .015, 95% CI [.006, .024]; sr2 = .029; p = .002; See Figure 1). No association between distress and safety behavior was noted among individuals reporting fewer stressors (β = −.040; B = −.002, 95% CI [−.013, .008]; sr2 = .003; p = .346). Contrary to hypotheses, no interactive effects with objective accident severity were noted.

Table 4.

Standardized regression coefficients and effect sizes for hierarchical Safety/Caution, Performance Deficit, and Aggressive/Hostile models

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | sp2 | B | SE | β | sp2 | B | SE | β | sp2 | |

| CAUT | ||||||||||||

| Sex | .567 | .145 | .214*** | .046 | .486 | .155 | .184** | .030 | .483 | .153 | .183** | .029 |

| Obj | .005 | .025 | .012 | .000 | .004 | .025 | .008 | .000 | ||||

| Sub | .007 | .004 | .118* | .011 | .006 | .004 | .102 | .008 | ||||

| Stress | .035 | .039 | .050 | .002 | .035 | .040 | .049 | .002 | ||||

| SxObj | −.016 | .014 | −.069 | .004 | ||||||||

| SxSub | .005 | .002 | .157** | .020 | ||||||||

| R2=.046*** | R2=.063*** | ΔR2 = .017 | R2=.083*** | ΔR2 = .020* | ||||||||

| PERF | ||||||||||||

| Sex | .240 | .098 | .137* | .019 | .232 | .105 | .132* | .015 | .230 | .104 | .131* | .015 |

| Obj | −.014 | .017 | −.050 | .002 | −.016 | .017 | −.055 | .003 | ||||

| Sub | .003 | .003 | .066 | .004 | .002 | .003 | .055 | .002 | ||||

| Stress | .028 | .027 | .060 | .003 | .031 | .027 | .066 | .004 | ||||

| SxObj | −.018 | .010 | −.117 | .011 | ||||||||

| SxSub | .003 | .001 | .149* | .018 | ||||||||

| R2=.019* | R2=.027 | ΔR2 = .008 | R2=.048* | ΔR2 = .021* | ||||||||

| ANG | ||||||||||||

| Sex | −.050 | .153 | −.018 | .000 | −.042 | .160 | −.015 | .000 | −.044 | .160 | −.016 | .000 |

| Obj | −.007 | .026 | −.016 | .000 | −.009 | .026 | −.019 | .000 | ||||

| Sub | .006 | .004 | .090 | .006 | .005 | .004 | .078 | .005 | ||||

| Stress | .139 | .041 | .191*** | .035 | .140 | .041 | .192** | .035 | ||||

| SxObj | −.014 | .015 | −.059 | .002 | ||||||||

| SxSub | .004* | .002 | .119* | .012 | ||||||||

| R2=.000 | R2=.045** | ΔR2 = .045** | R2=.056** | ΔR2 = .011 | ||||||||

Note:

p<.001;

p≤ .01;

p≤ .05;

ΔR2= change in R2; Obj = objective accident severity; Sub = subjective accident distress; Stress = life stress history (number of events); SxObj = interaction of stress history and objective severity; SxSub = interaction of stress history and subjective distress

Figure 1.

Interaction of subjective accident severity and life stress history on exaggerated safety/caution behavior

——— High Stress History (1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

3.2. Anxiety-Based Driving Errors

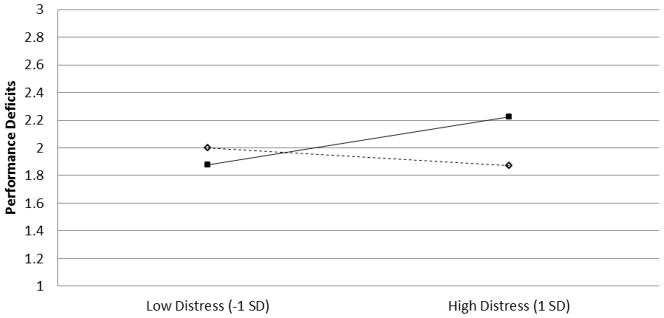

Participant sex evidenced an initial association with the frequency of anxiety-based performance deficits (adjR2 = .016) with women reporting more frequent performance errors than men (β = .137, sr2 = .019; p = .015). Inclusion of direct effects in the second step of the analysis (adjR2 = .014) contributed no additional variance to performance deficits (ΔR2 = .008; p = .465). Interaction terms introduced in the final step (adjR2 = .029), however, resulted in a significant increase in predicted variability (ΔR2 = .021; p = .034). An interactive effect of stress history and subjective accident distress was observed in the full model (β = .149; sr2 = .018; p = .016). Simple slopes analyses indicate a direct relationship between accident distress and performance deficits among individuals reporting greater frequency of life stress (β = .189; B = .008, 95% CI [.001, .014]; sr2 = .018; p = .017; See Fig. 2) with no relationship among those reporting fewer stressors (β = −.080; B = −.003, 95% CI [−.010, .004]; sr2 = .003; p = .346). No effects of objective accident severity were observed.

Figure 2.

Interaction of subjective accident severity and life stress history on anxiety-based performance deficits

——— High Stress History (1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

3.3. Aggressive/Hostile Behavior

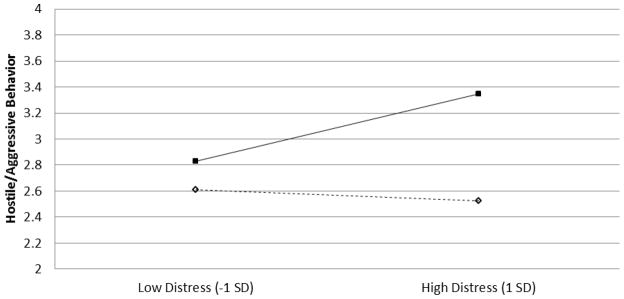

Contrasting previous models, participant sex evidenced no association with aggressive/hostile driving behavior in the initial step of the analysis (adjR2 < .000). Inclusion of direct effects in the second step (adjR2 = .033) improved the model (ΔR2 = .045; p = .003) and revealed a direct relationship between stress history and hostile/aggressive driving behavior (β = .191; sr2 = .035; p = .001). Inclusion of interaction terms in the final step (adjR2 = .038) did not contribute additional variance above and beyond the direct effects (ΔR2 = .011; p = .154); however, a modest interaction of subjective distress and life stress was observed (β = .119; sr2 = .012; p = .054). Given similar effects noted within the safety/caution and performance deficit models, this interaction was examined despite the lack of an overall contribution to variance in aggressive driving behavior. As with previous models, accident distress evidenced a significant relationship with hostile/aggressive behavior among individuals reporting more extensive life stress (β = .185; B = .012, 95% CI [.002, .021]; sr2 = .017; p = .019; See Fig. 3) with distress and aggressive behavior unrelated in those reporting fewer stressors (β = −.029; B = −.002, 95% CI [−.013, .009]; sr2 <.001; p = .743).3

Figure 3.

Interaction of subjective accident severity and life stress history on hostile/aggressive driving behavior

——— High Stress History (1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

Low Stress History (−1 SD)

4.0. Discussion

Contrasting early conditioning theories, contemporary models of anxiety highlight the role of life history and contextual factors in determining the occurrence and persistence of problematic anxiety (Craske, 1999; Mineka & Zinbarg, 1994). Interactive effects of stress history and accident distress on safety/caution, performance deficit, and hostile/aggressive driving behaviors in the current study support these predictions. As hypothesized, accident distress - indexed by ratings of fear, helplessness, danger, control, and certainty of death - demonstrated a positive relationship with anxious driving behaviors specifically among participants endorsing a large number of stressful life events (i.e., approximately four or more). Among individuals reporting less stress history (i.e., fewer than one additional stressor), accident distress was unrelated to any domain of anxious behavior. These relationships suggest that stress history may confer risk for anxious driving behavior by strengthening the influence of accident-related distress. Hypotheses regarding associations with objective accident severity were not supported, however, implying that emotional response to accident involvement may be a more salient predictor of anxious responding.

Although consistent with theoretical models of anxiety, modest effect sizes indicate that additional factors are needed to more fully account for variability in anxious driving behavior. The pattern of associations noted within these analyses suggests a number of potential influences. For example, increased tendency for avoidance-oriented coping may prove particularly germane to exaggerated safety/caution behavior. Given that stress exposure is believed to contribute to the development of maladaptive coping styles (Craske, 1999), avoidant coping, particularly among individuals endorsing more intensive stress history, will be relevant for continued investigation of exaggerated safety/caution behavior. Similarly, rumination and threat bias may account for variability in anxiety-based performance deficits. Anxiety-related driving impairments are hypothesized to be a byproduct of competing cognitive demand (J. Taylor et al., 2008; Matthews et al., 1998), implying that anxious rumination and/or biases towards external threat may contribute directly to anxiety-related driving deficits. Finally, trait anger is likely to influence the development of hostile/aggressive driving behavior. Although anxiety-related hostility/aggression is conceptualized as a specific reaction to driving situations perceived as threatening, individuals characterized by elevated trait anger would be expected to demonstrate more frequent anxiety-specific driving aggression.

Attention to the temporal relationship between life stressors and accident involvement also will be important for continued research in this area. Behavioral models posit that stressors occurring both before and after exposure to an aversive, fear-related event may impact anxious response although through somewhat different mechanisms. Early stress exposure is proposed to enhance fear conditionability and facilitate development of maladaptive coping styles (Craske, 1999). Elevated fear conditioning and ineffective coping as a consequence of early stress exposure may increase risk for subsequent anxious driving behavior. Stress events occurring after accident involvement, by contrast, may compound anxious responding through a process known as inflation. Inflation occurs when mildly conditioned anxiety (e.g., mild anxious behavior in response to accident exposure) is strengthened following exposure to a highly aversive, but unrelated, stressful experience (Mineka & Zinbarg, 1995). Results of the current research indicate that individuals reporting greater stress history are at increased risk for anxious driving behavior; examination of the temporal relationship between stress events and accident exposure may to help clarify specific mechanisms by which this stress-related risk occurs.

Gender effects noted in the driving anxiety literature also warrant further examination. Elevated frequency of safety/caution behaviors and anxiety-related performance deficits among female participants is consistent with research demonstrating elevated rates of driving anxiety and anxiety-related difficulties more broadly (e.g., J. Taylor & Paki, 2008; McLean & Anderson, 2009). Interestingly, hostile/aggressive driving behavior was unrelated to participant sex. Programmatic research presented by Deffenbacher and colleges (Deffenbacher, Oetting, Lynch, & Morris, 1996; Deffenbacher et al., 2000; Deffenbacher, Huff, Lynch, Oetting, & Salvatore, 2001) provides little evidence of gender differences in the experience of general driving anger. Although males sometimes demonstrate greater behavioral expressions of anger, these authors caution that gender effects in the driving anger literature are generally small and inconsistent. Variability in this literature suggests that continued examination of sex differences specific to anxiety-related hostile/aggressive behaviors is needed.

Several methodological considerations are important when contextualizing these results. This project examined anxious driving behavior exclusively among individuals reporting a history of traffic collisions. Whereas accident involvement is known to contribute to driving anxiety in a subset of individuals, etiological research notes that driving anxiety is linked to a broad range of aversive experiences including panic symptoms, social fears, and driving situations perceived to be generally threatening (Ehlers et al., 1994; J. Taylor & Deane, 1999, 2000). Traffic collisions were specifically chosen as the context for the current study given that motor vehicle accidents are (a) an easily identifiable event known to be associated with driving anxiety and (b) provide a common incident from which to assess contextual factors associated with an aversive event. As such, individuals having experienced a traffic collision are a useful sample in which to examine predictions regarding influences on anxious driving behavior. Exclusion of non-accident populations limits direct generalization, but it is likely that patterns of risk noted in the current report will be relevant within the larger population of fearful drivers.

Continued research in this area also will be strengthened through the incorporation of participants recruited specifically for elevated levels of travel anxiety. Although inclusion of individuals having experienced a traffic collision increased the likelihood of capturing a broad range of anxious behavior, no assumptions were made regarding levels of driving-related fear in this sample. Data presented in this report are able to address associations between stress history and accident involvement on a broad continuum, but results await replication in a sample of individuals reporting greater levels of driving anxiety.

Participants in this research also were relatively homogenous with respect to education, ethnicity, and most notably age. Younger motorists, such as those included in the current study, are characterized by limited driving experience, more frequent risk-taking behavior, and lower perceptions of personal driving risk (e.g., Arnett, Offer, & Fine, 1997; Machin & Sankey, 2008; Ulleberg, 2002). Although it is uncertain how the characteristics of youthful drivers impact these data, it is possible that generally lower perceptions of global risk may attenuate relationships between contextual factors and anxious driving behaviors. Elevated rates of accident involvement among younger motorists make college students a particularly relevant population; however, it is unclear how relationships observed in this study will generalize the more broad population of motorists.

Reliance on self-reported accident involvement, life stress history, and anxious driving behavior is an additional limitation of this research. As noted by previous authors (Gray et al. 2004), some forms of data including accident related variables (i.e., accident-related distress) and life stress history often are constrained by self-report methodology. Evidence supporting the psychometric properties of self-report measures used in this research provides some confidence in the observed relationships, but limitations inherent to this form of data should be considered when interpreting results.

A growing literature is beginning to demonstrate specific pathways in which driving anxiety may manifest as disruptive behaviors among those individuals who continue to drive. Along with increased potential for negative driving outcomes as a consequence of avoidant, disorganized, and aggressive behaviors, compensatory actions believed to underlie these reactions may ultimately serve to perpetuate driving-related fear. Identification of anxious driving behaviors and recognition of factors contributing to their development may be useful in guiding intervention for those seeking assistance with travel-related anxiety. Relationships observed in the current study identify stress history as a common vulnerability factor for anxious behavior among individuals with a history of traffic collisions. Processes contributing to the development of anxious driving behavior appear to parallel those hypothesized to contribute to anxiety more generally, suggesting that current learning models will continue to be useful in guiding research in this area.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health awarded to Joshua D. Clapp (F31 MH083385)

Footnotes

Inclusion criteria did not require the participant to be the driver in the reported accident.

Ratings for perceived control were reverse coded to remain congruent with ratings for subjective fear, helplessness, danger, and certainty of death

Life stress was modeled as a moderator of the relationship between accident distress and hostile/aggressive behavior to remain consistent with previous analyses. Examination of the interaction with accident distress as the moderator provides a direct relationship between stress history and hostile/aggressive behavior at high levels of accident distress (β = .299; B = .217, 95% CI [.015, .330]; sp2 = .044; p < .001) with no relationship at low levels of distress (β = .085; B = .062, 95% CI [−.052, .175]; sp2 = .003; p = .284).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnett JJ, Offer D, Fine MA. Reckless driving in adolescence: “State” and “Trait” factors. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 1997;29:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)87007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) Boston, MA: National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ. After the crash: Psychological assessment and treatment of survivors of motor vehicle accidents. 2. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Hughes D, George LK. Stressful life events and the onset of a generalized anxiety syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:1178–1183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney DS. Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:235–239. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG. Initial posttraumatic stress response following motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:223–234. doi: 10.1007/BF02110657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Olsen SA, Beck JG, Palyo SA, Grant DM, Gudmundsdottir B, et al. The Driving Behavior Survey: Scale development and validation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. Anxiety disorders: Why they persist and how we treat them. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:S5–S27. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG. Anxiety disorders: Psychological approaches to theory and treatment. New York: Westview Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Huff ME, Lynch RS, Oetting ER, Salvatore NF. Characteristics and treatment of high-anger drivers. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Lynch RS, Filetti LB, Dahlen ER, Oetting ER. Anger, aggression, risky behavior, and crash-related outcomes in three groups of drivers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:333–349. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, Lynch RS, Morris CD. The expression of anger and its consequences. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:575–590. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher JL, Huff ME, Lynch RS, Oetting ER, Salvatore NF. Characteristics and treatment of high-anger drivers. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;47:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dougall AL, Ursano RJ, Posluszney DM, Fullerton CS, Baum A. Predictors of posttraumatic stress among victims of motor vehicle accidents. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:402–411. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Hofmann SG, Herda CA, Roth WT. Clinical characteristics of driving phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1994;8:323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Bryant B. Psychological predictors of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:508–519. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Pallanti S. Recent life events and panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;146:622–626. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommberger UH, Stieglitz RD, Nyberg E, Schlickewei W, Kuner E, et al. Prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder by immediate reactions to trauma: A prospective study in road traffic accident victims. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1998;248:316–321. doi: 10.1007/s004060050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment. 2004;4:330–341. doi: 10.1177/1073191104269954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Gudanowski DM. Prewar factors in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:520–531. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontogiannis T. Patterns of driver stress and coping strategies in a Greek sample and their relationship to aberrant behaviors and traffic accidents. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2006;38:913–924. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin MA, Sankey KS. Relationships between young drivers’ personality characteristics, risk perceptions, and driving behavior. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2008;40:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Dorn L, Hoyes TW, Davies DR, Glendon AI, Taylor RG. Driver stress and performance on a driving simulator. Human Factors. 1998;40:136–149. doi: 10.1518/001872098779480569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayou R, Bryant B, Ehlers A. Prediction of psychological outcomes one year after a motor vehicle accident. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1231–1238. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayou R, Simken S, Threlfall J. The effects of road traffic accidents on driving behaviour. Injury. 1991;22:365–368. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(91)90095-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Zinbarg R. Conditioning and ethological models of anxiety disorders: Stress-in-dynamic-context anxiety models. In: Hope DA, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1995: Perspectives of anxiety, panic, and fear. Current theory and research in motivation. Vol. 43. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1995. pp. 135–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowrer OH. Learning Theory and Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Munjack DJ. The onset of driving phobias. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1984;15:305–308. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(84)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Deane FP. Acquisition and severity of driving-related fears. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1999;37:435–449. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Deane FP. Comparison and characteristics of motor vehicle accident (MVA) and non-MVA driving fears. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2000;14:281–298. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Deane FP, Podd J. Driving-related fear: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:631–645. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Deane FP, Podd J. Driving fear and driving skills: Comparison between fearful and control samples using standardised on-road assessment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:805–818. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Deane FP, Podd J. The relationship between driving anxiety and driving skill: A review of human factors and anxiety-performance theories to clarify future research needs. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2008;37:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J, Paki D. Wanna drive? Driving anxiety and fear in a New Zealand Community Sample. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2008;37:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Koch WJ. Anxiety disorders due to motor vehicle accidents: Nature and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:721–738. [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety and panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1991;19:6–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;150:620–624. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulleberg P. Personality subtypes of young drivers: Relationship to risk taking preferences, accident involvement, and response to a traffic safety campaign. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behavior. 2002;4:279–297. [Google Scholar]