Abstract

Purpose

This retrospective analysis sought to investigate the safety, feasibility and outcomes of platinum doublet therapy in patients age 70 or older with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) compared with patients younger than age 70 who participated in two randomized phase III trials conducted by the Southwest Oncology Group.

Patients and Methods

Outcomes and toxicity data from fit patients with stage IIIB or stage IV NSCLC treated with cisplatin/vinorelbine (CV) and carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP) were pooled from SWOG trials 9308 (S9308) and 9509 (S9509) and compared with respect to age.

Results

A total of 616 patients were available for efficacy analyses, of which 122 (20%) were ≥ 70 years of age. The median progression free survival (PFS) was 4 months in both age groups (p=0.71) and response rates (RR) were similar. Overall survival was significantly higher in the younger patient cohort (median 9 months vs. 7 months, p=0.04) Individual parameters of toxicity were similar in both age groups.

Conclusion

While patients ≥ 70 derived initial benefit from platinum based therapy, survival was better in younger patients. Additional studies in this growing patient population are needed to develop treatment strategies that minimize toxicity and increase efficacy.

INTRODUCTION

Advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains a challenging disease. Recent demographic trends reveal that NSCLC is increasingly becoming a disease of older patients. The median age of newly diagnosed patients in the United States is now 70 years. (1) It is estimated that in the year 2050, more than 400,000 new patients with lung cancer will be diagnosed in the United States, which is more than double the number of patients diagnosed in the year 2000. (2) Not only will a significant proportion of patients be older than age 70, 15% will be 85 years of age or older. This trend sends an urgent message to identify treatments that are both effective and well tolerated by older patients, where the balance between efficacy and toxicity is often more delicate.

Chemotherapy has been shown to both prolong survival and improve quality of life in patients with metastatic NSCLC. (3, 4) Combination chemotherapy, specifically platinum-based doublet therapy remains the cornerstone of treatment for fit patients with advanced NSCLC. (5,6) Many clinicians have concerns about aggressive treatment for elderly patients and as a result, the use of chemotherapy in patients with advanced lung cancer decreases with age and a substantial proportion of older patients do not receive active therapy. (7, 8, 9) However, large series have demonstrated that while comorbid illness or compromised performance score can predict for poor outcomes for NSCLC patients treated with chemotherapy, patients with advanced age and a good performance status can derive a similar degree of benefit from chemotherapy compared to younger patients. (10–13)

Randomized trials for elderly patients have been limited to non-platinum based regimens. Single agent chemotherapy, specifically vinorelbine, has been shown to increase survival and improve lung cancer related symptoms in elderly patients compared to best supportive care (BSC). (14) However, a subsequent large randomized phase III trial (15) in elderly patients found no additional survival benefit with the combination of gemcitabine and vinorelbine compared with either agent alone. The benefit of combination chemotherapy, specifically platinum-based chemotherapy is less clear, as no large prospective randomized phase III trial testing platinum based therapy in an elderly-specific trial has been fully reported to date. Lilenbaum et al prospectively analyzed patients ≥ age 70 in a trial comparing carboplatin and paclitaxel to paclitaxel alone and found no difference in survival between the younger and elderly patients for either arm. (16) Second line chemotherapy, though, has been shown to provide benefit for elderly patients with advanced NSCLC with similar toxicity as younger patients. (17)

The literature suggests that toxicity is increased in older patients treated with chemotherapy, particularly hematologic toxicity, though data are conflicting. In a retrospective analysis of elderly patients with advanced NSCLC who participated in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) trials, (18) more leucopenia was noted in patients over 70, though rates of infection and thrombocytopenia were not different in patients treated with either cisplatin and etoposide or a combination of high or low dose paclitaxel and cisplatin. In another retrospective series using two, three and four drug cisplatin-based combinations, increased myelotoxicity was seen in elderly patients being treated for advanced NSCLC, (19) but it is not clear if this holds true for modern platinum doublet therapy. A smaller retrospective series of elderly patients treated with carboplatin/paclitaxel did not find any difference in hematologic or non hematologic toxicity between patients older or younger than age 70. (20) In addition, the small subset of patients over age 70 participating in ECOG 1594, which compared platinum based doublets in advanced NSCLC, found equivalent toxicity and outcomes between patients under the age of 70 and those between 70 and 80. (21)

In an effort to determine the potential benefit, toxicity and feasibility of platinum-based combination chemotherapy in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) has undertaken an analysis of S9308 (22) and S9509, (23) two phase III studies published previously on the use of platinum-based combination therapy in advanced NSCLC. This retrospective analysis combines the results and toxicity data from both studies and divides patients into two groups: patients younger than 70 and those 70 or older who received combination platinum-based therapy. The two cohorts were compared with respect to baseline characteristics, number of chemotherapy cycles given, toxicity, response and survival. Herein we describe the results of this analysis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were recruited from SWOG-affiliated sites in the United States. Eligibility criteria for S9308 and S9509 were similar and included patients with stage IV disease and selected stage IIIB patients with either pleural effusions or multiple ipsilateral lung nodules. All patients were required to have histologically confirmed NSCLC with measurable or assessable disease. Patients with brain metastases were excluded. Patients were required to have a performance status of 0 or 1. Previous chemotherapy was an exclusion criterion, but prior radiation and surgery were permitted. Adequate organ function and hematologic parameters were mandated. Both studies were approved by the institutional review board at each participating site and signed informed consent from all patients was required.

In both studies, patients were stratified by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), stage (IIIB or IV), disease status (measurable or nonmeasurable), prior surgery or radiation and histology (squamous cell, large cell, adenocarcinoma or unspecified). Patients in S9509 were also stratified by weight loss (greater or less than 5%).

Treatment schedule

In S9308, patients were randomized to cisplatin alone or cisplatin plus vinorelbine (CV). Cisplatin was given every four weeks at a dose of 100mg/m2 on both arms. Patients in the combination arm also received vinorelbine 25mg/m2 weekly. Standard administration of cisplatin included hydration, diuresis and an antiemetic regimen. In addition to prespecified dose reductions for cytopenias, a creatinine of 1.6 or greater or a creatinine clearance of 50 mL/minute or less warranted reducing or holding the cisplatin dose, while hyperbilirubinemia mandated dose reductions of vinorelbine.

Response and toxicity for S9308 were measured according to standard SWOG criteria.(24) Patients remained on study until progression of disease, unacceptable toxicity determined by the treating physician and the study coordinator, a delay in treatment of more than four weeks, institution of palliative radiation or patient refusal.

In S9509, patients were randomized to carboplatin and paclitaxel (CP) or cisplatin and vinorelbine. Cisplatin and vinorelbine were given in the same dose and schedule as in S9308: cisplatin 100mg/m2 every four weeks and vinorelbine 25mg/ m2 weekly. Paclitaxel was given at 225mg/m2 with carboplatin given at an AUC of 6 every three weeks. Standard administration of cisplatin was used with appropriate hydration, diuresis and antiemetics. Prophylaxis against hypersensitivity to paclitaxel administration was also given using dexamethasone, antihistamines and H2 blockers. Dose adjustments were made for hematologic toxicity, decline in renal function or neurotoxicity.

Standard SWOG criteria were used to determine response in S9509 and toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria version 2.0. (25) Patients remained on study until progression of disease, unacceptable toxicity as determined by the treating physician and the study coordinator, a delay in treatment of more than two weeks, need for palliative radiation or patient refusal. In the absence of progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity, patients were treated with a minimum of six cycles or two cycles past best response to a maximum of ten cycles.

Statistical methods

Fisher’s Exact test was used for comparisons between categorical variables (patient characteristics, response, adverse events). Comparisons between continuous variables were performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum or t-test. Survival estimates were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier. (26) Confidence intervals for the median were calculated using the method of Brookmeyer and Crowley. (27) The differences between survival curves were compared using the log rank test. The difference between Kaplan-Meier point estimates were performed with a t-test using standard errors based on Greenwood’s formula. To adjust for multiple comparisons, permutation tests were performed (with 1000 permutations).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

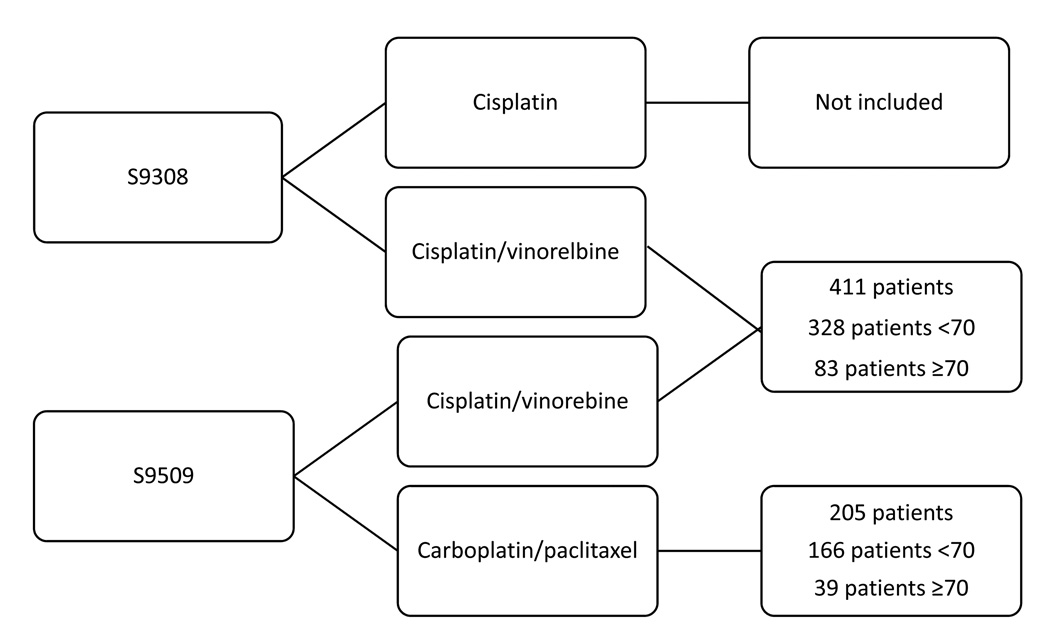

A total of 616 patients who received combination chemotherapy in trials S9308 and S9509 were eligible for this analysis. For the purposes of analysis, patients treated with CV were pooled from S9308 and S9509 (Figure 1). Of the 616 patients, 122 (20%) were ≥ age 70, including six patients 80 years of age or older. The median age was 63 for patients enrolled on S9308 and 62 for patients enrolled on S9509. The proportion of patients who were elderly was similar in each chemotherapy regimen with 39 patients ≥ age 70 treated with CP (19%) and 83 patients treated with CV (20%).

Figure 1.

Patient groups by treatment

Table 1 displays the patient characteristics broken down by age category (< 70; ≥ 70). Most patients had stage IV disease with a smaller proportion of patients with stage IIIB disease. There were slightly fewer patients in the younger age group with stage IIIB disease, but this was not statistically significant (p=0.18). The proportion of patients with performance status of 0 or 1 was similar in both age groups, as was weight loss (defined as greater or less than 5% during the 6 months prior to study enrollment). The majority of patients (82%) were Caucasian and males constituted approximately two-thirds of all patients with similar percentages in both groups. A small proportion in each group had received prior radiation or surgery.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Age < 70 | Age ≥ 70 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 341 | 69% | 80 | 66% | 421 | 68% |

| Female | 153 | 31% | 42 | 34% | 195 | 32% |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 80 | 16% | 8 | 7% | 88 | 14% |

| White | 393 | 80% | 111 | 91% | 504 | 82% |

| Other/Unknown/ Not Reported |

21 | 4% | 3 | 2% | 24 | 4% |

| Performance Status* | ||||||

| PS 0 | 179 | 37% | 39 | 33% | 218 | 36% |

| PS 1 | 310 | 63% | 79 | 67% | 389 | 64% |

| Weight Loss ** | ||||||

| < 5% | 260 | 54% | 66 | 56% | 326 | 55% |

| ≥ 5% | 220 | 46% | 52 | 44% | 272 | 45% |

| Stage*** | ||||||

| IIIB | 47 | 10% | 17 | 14% | 64 | 10% |

| IV | 447 | 90% | 105 | 86% | 552 | 90% |

| Prior Treatment | ||||||

| Radiation | 74 | 15% | 18 | 15% | 92 | 15% |

| Surgery | 111 | 23% | 25 | 21% | 136 | 22% |

| Not reported | 150 | 30% | 38 | 31% | 188 | 31% |

Of 607 evaluable patients, not statistically different (p=0.52)

of 598 evaluable patients, not statistically different (p=0.76)

of 616 evaluable patients, not statistically different (p=0.18)

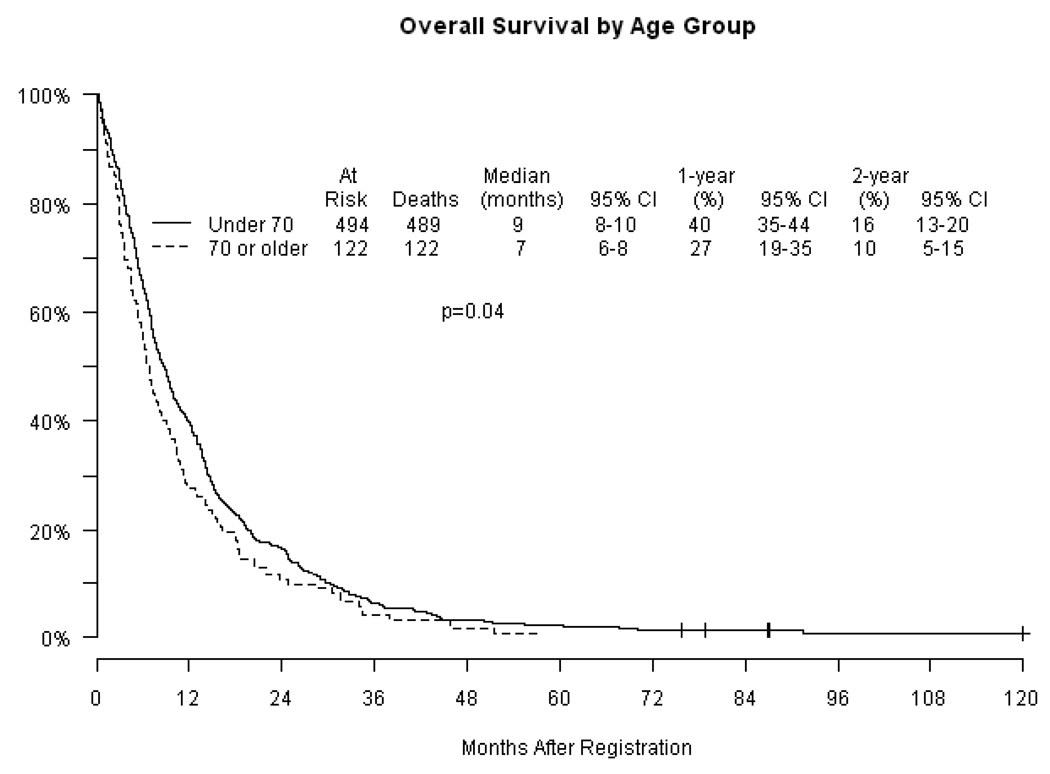

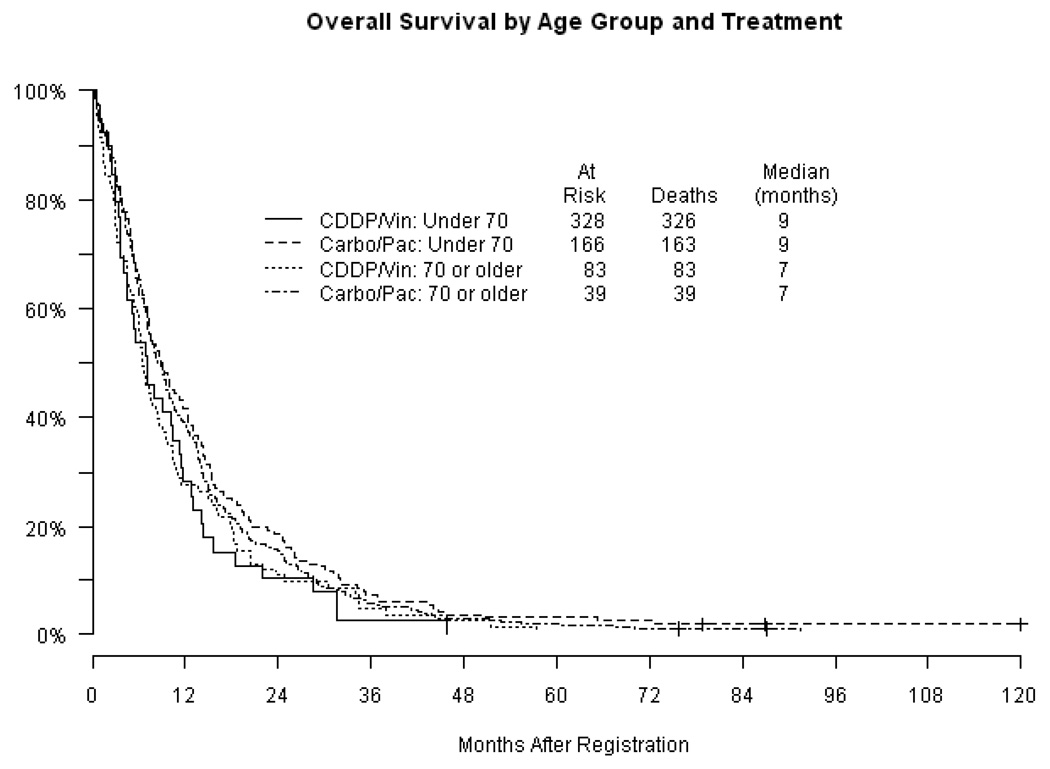

Efficacy

Response rates (Table 2) were similar in each age category with approximately one-quarter of patients experiencing an objective response. Nearly all responses were partial. The remainder of patients had either stable or progressive disease. The estimated median progression-free survival (PFS) (Figure 2) was 4 months in both age groups (p = 0.71). Overall survival (OS) is displayed in Figure 3 by age groups (Figure 3a) and by age groups according to treatment (Figure 3b). Median overall survival estimates were 9 months and 7 months in the < 70 and ≥ 70 age groups respectively (p=0.04). The proportion of patients surviving at one year was 40% in the group under 70 compared with 27% in patients ≥ 70 (p=0.01). Two-year survival was 16% and 10% in the younger and older cohorts respectively (p=0.07). The specific chemotherapy regimen did not impact OS or PFS in either age group. A Cox regression analysis adjusting for treatment arm, stage, performance status and weight loss was unable to detect an association between age and PFS with a p-value of 0.89, but was significant for an association with OS with a p value of 0.05.

Table 2.

Response rates by age

| Age<70 N=494 |

Age≥70 N=122 |

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | 95% CI | No | % | 95% CI | |||

| Overall response (PR+CR) |

131 | 27 | 23–31% | 36 | 30 | 22–38% | 0.51 | |

| Complete | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Partial | 126 | 26 | 35 | 29 | ||||

| No response | 363 | 73 | 86 | 70 | ||||

| Stable disease | 146 | 30 | 35 | 29 | ||||

| Progressive Disease | 140 | 28 | 27 | 22 | ||||

| Not assessable | 77 | 16 | 24 | 20 | ||||

Abbreviations: PD, progressive disease; SD, stable disease; PR, partial response; CR, complete response

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival(PFS) by age and treatment

Figure 3.

Figure 3a. Overall survival (OS) by age

Figure 3b. Overall survival by age and treatment cisplatin/vinorelbine (CDDP/Vin); carboplatin/paclitaxel (Carbo/Pac)

Treatment Delivery

The median number of chemotherapy cycles completed for patients younger than 70 was 4 (interquartile range: 2–6 cycles), while patients aged ≥ 70 completed a median of 3 cycles (interquartile range: 2–5 cycles), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). There was a significant difference in the subset of patients who received CV with patients ≥ 70 receiving a median of 2 cycles of therapy compared with patients <70 who received a median of 3 cycles (p= 0.01 and remained significant when adjusted for multiple comparisons). There was no significant difference between age groups in the subset of patients treated with CP with patients ≥ 70 receiving a median of 4 cycles and those <70 receiving a median of 5 cycles (p=0.7). The most common reason for discontinuing treatment in the younger cohort was disease progression, with 41% of patients younger than 70 stopping treatment for that reason. In patients ≥ 70, toxicity was the most common reason for treatment discontinuation, being noted in 36% of patients.

Toxicity

All patients included in the efficacy analysis were included in the toxicity analysis (Table 3) except for 9 patients: 7 in the CV group and 2 in the CP group. Hematologic toxicity was similar in both groups. Notably, 76% and 83% of patients in the group under 70 and the group ≥ 70, respectively, experienced grade 3–5 hematologic toxicity. Neutropenia represented the largest percentage of grade 3–5 toxicity in each group though rates of infection were much lower. Similarly, the groups did not differ significantly in terms of non-hematologic toxicity with rates of grades 3–5 toxicity of 53% in the under 70 group and 57% in the ≥ 70 group respectively. Neuropathy was common, though for the majority of patients in both groups, it was grade 1–2. Of note, a larger proportion of patients in the older age group experienced a maximum toxicity of grades 3–5 (94%) compared with the younger age group (87%), but this difference was not statistically significant when adjusted for multiple comparisons. In addition, there was no difference in toxicity between the group < 70 and the group ≥ 70 when each chemotherapy regimen (CV or CP) was analyzed separately. Among patients younger than 70 and patients 70 years of age or older, there was a greater incidence of grade 3 or worse neuropathy among patients receiving CP compared with CV (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). In addition, among patients younger than 70 there was a higher incidence of grade 3 or greater hematologic toxicity in the CV arm (p < 0.001). The remainder of measured toxicity parameters were not significantly different between the two chemotherapy groups. There were 16 (3%) treatment related deaths in the group under 70 and 5 (4%) in the group ≥70 (p=0.64).

Table 3.

Toxicity, grades 3–5

| Age<70 | % | Age≥70 | % | Total | % | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 486 | N=121 | N=607 | ||||||

| Hematologic | 367 | 76% | 100 | 83% | 467 | 77% | 0.12 | |

| Anemia | 96 | 20% | 16 | 13% | 112 | 18% | 0.12 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 38 | 8% | 4 | 3% | 42 | 7% | 0.11 | |

| Neutropenia | 340 | 70% | 95 | 79% | 435 | 72% | 0.07 | |

| Febrile neutropenia* | 4 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 5 | 1% | 1.00 | |

| Infection | 64 | 13% | 15 | 12% | 79 | 13% | 0.88 | |

| Non-Hematologic | 260 | 53% | 69 | 57% | 329 | 54% | 0.54 | |

| Nausea | 66 | 14% | 12 | 10% | 78 | 13% | 0.36 | |

| Vomiting | 51 | 10% | 8 | 7% | 59 | 10% | 0.23 | |

| Diarrhea | 16 | 3% | 1 | 1% | 17 | 3% | 0.22 | |

| Mucositis | 6 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 1% | 0.60 | |

| Neuropathy | 30 | 6% | 9 | 7% | 39 | 6% | 0.68 | |

| Fatigue | 46 | 9% | 18 | 15% | 64 | 11% | 0.10 | |

| Maximum Grade Observed, Any Toxicity(3–5) | 424 | 87% | 114 | 94% | 538 | 89% | 0.04 | |

| Treatment related deaths | 16 | 3% | 5 | 4% | 21 | 3% | 0.64 | |

Febrile neutropenia data available only for S9509 (N=403)

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, patients ≥ 70 with advanced NSCLC treated with platinum-based doublet therapy achieved comparable short term benefit to younger patients, but overall survival was worse in the older cohort. While PFS and response rates were similar in the two groups, overall survival was significantly worse for patients ≥ 70. A Cox regression analysis that adjusted for treatment arm, stage, performance status and weight loss showed a similar result. No information is available regarding second line treatment in either patient group, which could certainly influence longer term outcomes. It is possible that older patients may receive second line chemotherapy less frequently than their younger counterparts, which may explain some of the difference in overall survival. There is a tendency toward increased comorbidities in elderly patients with NSCLC (9), which may result in an inherently inferior survival unrelated to the underlying malignancy in older compared to younger patients. This concept cannot be analyzed in our study as no baseline comorbidity data was recorded.

Toxicity is a major concern for older patients with advanced NSCLC and their treating physicians. Elderly patients treated with CV received fewer cycles of chemotherapy than their younger counterparts, while there was no statistically significant difference in treatment delivery by age in those patients treated with CP. However, there was no difference in toxicity according to age in patients treated with either CV or CP. Despite significant neutropenia in both groups, the rates of infection and neutropenic fever were low. In addition, only a small percentage of neuropathy was classified as grades 3–5 in either group. Of note, an increased percentage of older patients experienced a maximum grade of any toxicity in the 3–5 range, though this was not statistically significant. Our analysis along with prior observations suggest that close observation and prudent dose adjustments are warranted in elderly NSCLC patients receiving chemotherapy. (13, 18)

One advantage to this type of analysis is the ability to gather data on a larger group of elderly patients with NSCLC by pooling data from two different SWOG trials. In addition cisplatin and carboplatin based regimens remain the standard backbone of therapy for advanced NSCLC making this analysis relevant to current patient care.

However, the analysis is limited by its retrospective nature. In addition, the elderly patients participating in these two clinical trials may represent a select group of older patients that both fit the inclusion criteria of a performance status of 0–1 and were felt to be candidates for a clinical trial by their treating physician and may not be representative of the general population.

In this era of targeted therapies, new issues are emerging as to the potential benefit and risks of targeted agents in elderly patients with NSCLC. The ECOG 4599 trial (28) showed the benefit of adding bevacizumab to carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced NSCLC. A retrospective analysis (29) of patients over the age of 70 participating in this trial demonstrated increased grade 3 or above toxicity in elderly patients compared with younger patients, but without an efficacy benefit in the elderly. Both our analysis and the E4599 outcome-by-age report emphasize the need for increased participation of elderly patients in clinical trials as well as elderly-specific trials where feasible.

Although the treatment of NSCLC continues to evolve, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy remains the standard-of-care for patients with a favorable performance status. Our analysis suggests that while patients older than 70 may derive comparable initial benefit from platinum-based doublet therapy compared to younger patients, long-term outcomes may not be as favorable. Given the inherent limitations of retrospective analyses, only large scale age-specific prospective trials evaluating traditional therapies as well as newer targeted agents will provide more definitive information on appropriate therapeutic options for the rapidly growing cohort of older patients with advanced non small cell lung cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This clinical trial was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS: CA32102, CA38926, CA-22433, CA-35431, CA-58882, CA-04919, CA-46282, CA-37981, CA-20319, CA-42777, CA-35090, CA-45807, CA-14028, CA-67663, CA-35176, CA67575, CA-35281, CA-35261, CA-13612, CA-27057, CA-46441, CA-76429, CA-76447, CA58415, CA-35119, CA-58658, CA-58416, CA-35192, CA-45560, CA-12644, CA-52654, CA-68183, CA-46368, CA-35178, CA-74647, CA-58861, CA-35262, CA-28862, CA-58348, CA-46136, CA-12213, CA-58686, CA-46113, CA-45450, CA-76448, CA-45377, CA-63845, CA-63850, CA-63844, CA-52772, CA-45461, CA-16385, CA-35128, CA-76462, CA-35117, CA-52651, CA-52650, CA-58723, CA-35200

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1. [Accessed February 10, 2009];SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1875–2001. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov.

- 2.Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, et al. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) program. The Oncologist. 2007;12:20–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunn PA, Kelly K. New chemotherapeutic agents prolong survival and improve quality of life in non-small-cell lung cancer: A review of the literature and future directions. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1087–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomized clinical trials. Br Med J. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Accessed February 11, 2009];The NCCN Lung Cancer Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (Version v.2. 2009) © 2006 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. Available at: http://www.nccn.org.

- 6.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani C, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. New Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsey SD, Howlader N, Etzioni RD, Donato B, et al. Chemotherapy use, outcomes, and costs for older persons with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: Evidence From Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results–Medicare. J Clin Oncol. 2004;24:4971–4978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chrischilles E, Pendergast JF, Kahn KL, et al. Adverse events among the elderly receiving chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28:620–627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owonikoko TK, Ragin CC, Belani CP, et al. Lung cancer in elderly patients: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5570–5577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asmis TR, Ding K, Seymour L. Age and comorbidity as independent prognostic factors in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer: A review of National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:54–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billingham LJ, Cullen MH. The benefits of chemotherapy in patient subgroups with unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2001;12:1671–1675. doi: 10.1023/a:1013582618920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connell JP, Kris MG, Gralla RJ, et al. Frequency and prognostic importance of pretreatment clinical characteristics in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1604–1614. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.11.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocha Lima CMS, Herndon JE, Kosty M, et al. Therapy choices among older patients with lung carcinoma: An evaluation of two trials of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Cancer. 2002;84:181–187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study Group. Effects of vinorelbine on quality of life and survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:66–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Can Inst. 2003;95:362–372. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.5.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lilenbaum RC, Herndon JE, List MA, et al. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (study 9730) J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:190–196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss GJ, Langer C, Rosell R, et al. Elderly patients benefit from second-line cytotoxic chemotherapy: A subset analysis of a randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed compared with docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4405–4411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer CJ, Manola J, Bernado P, et al. Cisplatin-based therapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: implications of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 5592, a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:173–181. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubota K, Furuse K, Kawahara M, et al. Cisplatin based combination chemotherapy for elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:469–474. doi: 10.1007/s002800050689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensing TA, Peterman AH, Schell MJ, et al. The impact of age on toxicity, response rate, quality of life, and survival in patients with advanced, stage IIIB or IV nonsmall cell lung carcinoma treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Cancer. 2003;98:779–788. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langer CJ, Schiller J, Harrington DP, et al. Age-specific subanalysis of ECOG 1594: Fit elderly patients (70–80 YRS) with NSCLC do as well as younger pts (<70) Proc of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003 Abstract # 2571. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2459–2465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green S, Weiss GR. Southwest Oncology Group standard response criteria, endpoint definitions and toxicity criteria. Invest New Drugs. 1992;10:239–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00944177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bethesda, MD: Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute; National Cancer Institute: Common toxicity criteria (version 2) 1999 http://www.fda.gov/cder/cancer/toxicityframe.htm.

- 26.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. JASA. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brookmeyer R, Crowley J. A confidence interval for the median survival time. Biometrics. 1982;38:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler AB, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramalingam SS, Dahlberg SE, Langer CJ, et al. Outcomes for elderly, advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 4599. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:60–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]