Abstract

Vascular endothelial cells provide essential support to the tumor microenvironment, but little is known about the transcriptional control of endothelial functions during tumorigenesis. Here we define a critical role for the Forkhead transcription factor FoxM1 in modulating the development of tumor-associated endothelial cells. Pulmonary tumorigenesis induced by urethane administration was compared in mice genetically deleted for FoxM1 in endothelial cells (enFoxm1−/− mice). Notably, lung tumor number and size were increased in enFoxm1−/− mice. Increased tumorigenesis was associated with increased proliferation of tumor cells and increased expression of c-Myc and Cyclin D1. Further, perivascular infiltration by inflammatory cells was elevated and inflammatory cells in BAL fluid were increased. Expression of Flk-1 (VEGFR2) and FoxF1, known regulators of pulmonary inflammation, was decreased in enFoxm1−/− mice. siRNA-mediated knockdown of FoxM1 in endothelial cells reduced Flk-1 and FoxF1 expression, which was driven by direct transcriptional induction by FoxM1 as target genes. Endothelial-specific deletion of FoxM1 in vivo or in vitro also decreased expression of Sfrp1, a known inhibitor of canonical Wnt signaling, in a manner that was associated with increased Wnt signaling. Taken together, our results suggest that endothelial-specific expression of FoxM1 limits lung inflammation and canonical Wnt signaling in lung epithelial cells, thereby restricting lung tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Foxm1, Foxf1, Flk-1, Sfrp1

Introduction

Foxm1 (previously known as HFH-11B, Trident, Win, or MPP2) is a member of the Forkhead family of transcription factors that share homology in the Winged Helix/Forkhead DNA binding domain (1–2). Foxm1 expression is induced during cellular proliferation in a variety of cell types, including epithelial and endothelial cells (3–4). Foxm1, promotes G1/S and G2/M phases of cell cycle by directly activating transcription of regulatory genes such as Cdc25B, cyclin B1, Aurora B Kinase and Polo-like Kinase 1 (5–6). Foxm1 decreases nuclear levels of the CDK inhibitor proteins p21cip1 and p27kip1 by regulating their degradation through the ubiquitin ligase complex (7). Foxm1 is over-expressed in a variety of highly proliferative human cancers, including lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, as well as many other solid tumors (reviewed in (7–8) and (9)). Over-expression of Foxm1 significantly increased the number and size of tumors induced by the MCA/BHT lung tumor induction/promotion protocol (10). Deletion of Foxm1 from type II lung epithelial cells using a Cre/LoxP system significantly decreased the number and size of lung adenomas induced by either MCA/BHT or urethane (11). These data indicate that Foxm1 expression in tumor cells is essential for progression of chemically-induced lung cancer in vivo. However, the role of Foxm1 in tumor-associated endothelial cells remains unknown.

There is increased evidence that multiple cell types and processes contribute to the microenvironment associated with carcinogenesis. Supporting cells in the tumor microenvironment include inflammatory cells, endothelial cells and stromal fibroblasts. Non-tumor cells contribute both positive and negative growth signals to the tumor. These cells produce a variety of growth factors, chemokines, and matrix-degrading enzymes that enhance the proliferation and invasion of the tumor. Little is known about the molecular mechanisms controlling the cross-talk between tumor cells and other cells of tumor microenvironment.

Inflammation and angiogenesis are two major processes in tumor microenvironment that drives tumorigenesis (12). Activated inflammatory cells stimulate growth and progression of tumor cells. Inflammation, recurrent cell injury, and associated compensatory cell proliferation promotes the growth of malignant cells (13). Inflammatory cells also induce angiogenesis and ECM remodeling, further destabilizing epithelial cells during malignant transformation. Tumor associated angiogenesis is regulated by a number of signaling pathways, including VEGF-R2 (Flk1), angiopoietins, FGF, and PDGF pathways (14). Flk1 is predominately expressed in endothelial cells. VEGF-A/Flk1 signaling interaction has been shown to be necessary for angiogenesis, mediating endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and migration (15). Foxm1 increases the expression of VEGF-A in glioma cells (16), indicating the important role of Foxm1 in VEGF signaling and angiogenesis. Foxm1 is necessary for formation of the pulmonary vasculature during embryogenesis, and Foxm1−/− mice exhibited severe defects in the formation of peripheral pulmonary capillaries (17). Foxm1 deletion from endothelial cells delayed lung repair after injury by LPS (18). While these studies indicate that Foxm1 transcription factor is critical for development and repair of lung vasculature, the role of Foxm1 in tumor-associated endothelial cells remains unknown.

In present study, we utilized a genetic mouse model in which the Foxm1 gene was deleted from endothelial cells (Tie2-Cre/Foxm1fl/fl or enFoxm1−/− mice). Surprisingly, numbers and sizes of lung tumors were increased in enFoxM1−/− mice following urethane induction. Increased tumorigenesis in enFoxM1−/− lungs was associated with increased lung inflammation and increased canonical Wnt signaling.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic mice and lung tumorigenesis

The Foxm1fl/fl C57BL/6 mice (19) were bred with Tie2-Cre C57BL/6 mice to generate Tie2-Cretg/−/Foxm1 fl/fl (enFoxm1−/−) double transgenic mice. Foxm1fl/fl and Tie2-Cretg/− single transgenic mice were used as controls. Tumorigenesis was induced using either urethane protocol or 3-methylcholanthrene(MCA)/butylated hydroxytoluene(BHT) protocol as previously described (11). For urethane tumorigenesis, control and enFoxm1−/−male mice were injected i.p. with 1 mg/g of body weight of urethane once weekly for 6 consecutive weeks. At 30 weeks after the first urethane injection, lungs were harvested and tumors were counted using a dissecting microscope. For MCA/BHT tumorigenesis, MCA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was given as a single i.p. dose of 15 μg/g of body weight, followed by six weekly i.p. injections of BHT (200 μg/g of body weight; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Lungs were fixed, embedded into paraffin blocks, or used to prepare total lung RNA with RNA-STAT-60 (Tel-Test “B” Inc. Friendswood, TX). To examine the lung inflammation during early tumorigenesis, control and enFoxm1−/− mice were treated with urethane for 3 consecutive weeks. Three days following the final urethane injection broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was taken as described (20). To examine activity of canonical Wnt signaling pathway, control and enFoxm1−/− mice were crossed with TOPGAL reporter mice (21). Tie2-Cretg/−/Foxm1 fl/fl/TOPGAL and control mice were treated weekly with urethane for 6 consecutive weeks. Six weeks after the final injection, lungs were stained for β-gal activity using X-gal substrate as previously described (22). Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Animal care and Use committee of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Paraffin (5 μm) sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for morphological examination or immunostained with antibodies (listed in supplemental Materials and Methods) as described previously (10). Sections from β-gal stained lungs were immunostained with either Ki-67 or pro-SPC, and counterstained with nuclear fast red (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Immunofluorescent staining was performed using antibodies listed in supplemental Materials and Methods).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total lung RNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR using StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were amplified with Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) combined with inventoried Taqman gene expression assays (supplemental Table 1).

siRNA transfection, luciferase assay and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Mouse endothelial cell line MFLM-91U was provided by Dr. Akeson (23). MFLM-91U cells express endothelial-specific VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, Tie-1 and Tie-2 as demonstrated by immunostaining and qRT-PCR within last six months. Human endothelial cell line HMVEC-L was bought from ATCC one month before the experiments. MFLM-91U or HMVEC-L cells were transfected with 100 nmol/L of either Foxm1-specific siRNA (siFoxm1) or mutant control siFoxm1 (6) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in serum free media for 72 hours as described (6).

LUC reporter driven by −1.5kb Flk1 promoter (Flk1-LUC) was generated as described in Supplemental Materials and Methods. −2.7kb Foxf1-LUC vector was described previously (24). MFLM-91U cells were transfected with CMV-Foxm1b or CMV-empty plasmids, as well as with LUC reporters driven by either Flk1 or Foxf1 promoters. CMV-Renilla was used as an internal control to normalize transfection efficiency. Dual luciferase assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was performed 24 hours after transfection as described previously (25). ChIP assay was performed as described in supplemental Material and Methods and in (6).

Statistical analysis

We used Microsoft Excel Program to calculate SD and statistically significant differences between samples using the Student T Test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Urethane induced tumor formation after deletion of Foxm1 from endothelial cells

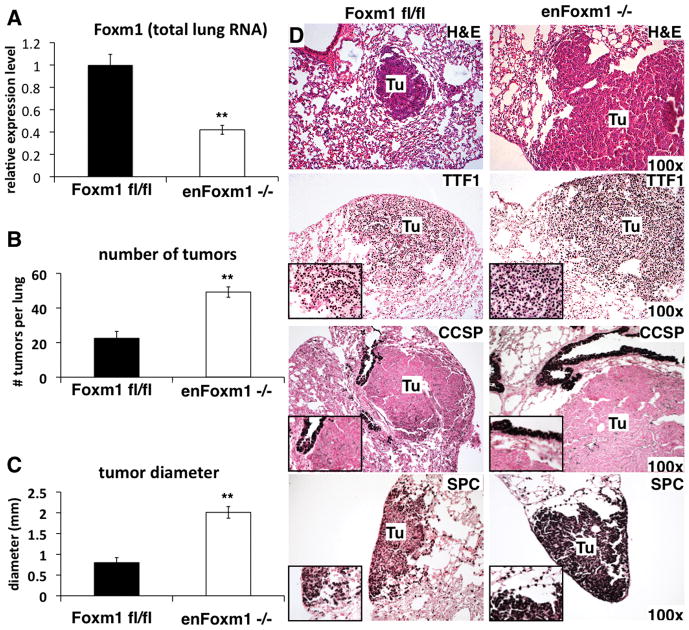

To determine the role of Foxm1 in endothelial cells during lung tumorigenesis, we utilized a double transgenic mouse model in which the Foxm1 gene is selectively deleted from endothelial cells (Tie2-Cretg/−/Foxm1 fl/fl or enFoxm1−/− mice). Previous studies demonstrated that in this mouse line Foxm1 was efficiently deleted in endothelial cells without affecting epithelial and inflammatory cells of the lung (18). Tie2 promoter expressed Cre-recombinase that excised exons 4–7, encoding the DNA binding domain and transcriptional activation domain of the Foxm1 protein. Consistent with published studies (18), Foxm1 mRNA was significantly decreased in total lung RNA from enFoxm1−/− mice (Fig. 1A). Foxm1 mRNA levels in control Foxm1fl/fl and Tie2-Cretg/− lungs were similar (data not shown). Lung tumorigenesis was induced using urethane injections. Thirty weeks after initial urethane injection, increased numbers of lung tumors were seen in enFoxm1−/− mice (Fig. 1B). Tumor diameters in enFoxm1−/− mice were significantly increased (Fig. 1C). The tumors in enFoxm1−/− mice were lung adenomas (Fig. 1D). To identify cell origin of the lung tumor cells, immunohistochemical staining was performed using antibodies against either pro-Surfactant-associated Protein C (SPC), a type II alveolar epithelial marker, or Clara cell specific protein (CCSP). All tumors in control and enFoxm1−/−mice were SPC-positive (Fig. 1D), likely indicating their origin from alveolar type II epithelial cells. CCSP-positive tumors were not found in either enFoxm1−/− or control lungs (Fig. 3D). Both enFoxm1−/− and control tumors expressed TTF-1 (Fig. 1D), a lung epithelial-specific transcription factor which is widely expressed in non-small cell lung cancers in mice and humans (26–27). Furthermore, increased lung tumorigenesis was observed in enFoxm1−/− mice after MCA/BHT treatment (Supplemental Fig. 1), a well-known protocol for lung tumor initiation/promotion (28), indicating that the effect of Foxm1 deletion in enFoxm1−/− mice is not limited to urethane tumorigenesis. These data demonstrated that deletion of Foxm1 from endothelial cells increased lung tumor burden after tumor induction.

Figure 1. Deletion of Foxm1 from lung endothelial cells increases tumor formation.

A. qRT-PCR analysis of Foxm1 mRNA expression in control Foxm1fl/fl and enFoxm1−/− lungs. RNA was isolated from the total lung. β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. B. Increase in the total number of urethane-induced tumors in enFoxm1−/− mice. enFoxm1−/− and control Foxm1fl/fl mice were administered 6 weekly urethane injections and lungs were harvested 30 weeks after initial urethane injection. C. Increased diameter of tumors in enFoxm1−/− mice. Mean number of tumors per lung (±SE) and mean tumor diameter (±SE) were calculated from n = 12 mouse lungs per group. D. H&E staining demonstrates an increase in the size of lung tumors (Tu) in enFoxm1−/− mice. Tumors in both enFoxm1−/− and control mice are TTF1- and SPC-positive, and CCSP-negative. Magnifications: panels D, 100x; insets, 400x. A p value <0.01 is shown with (**).

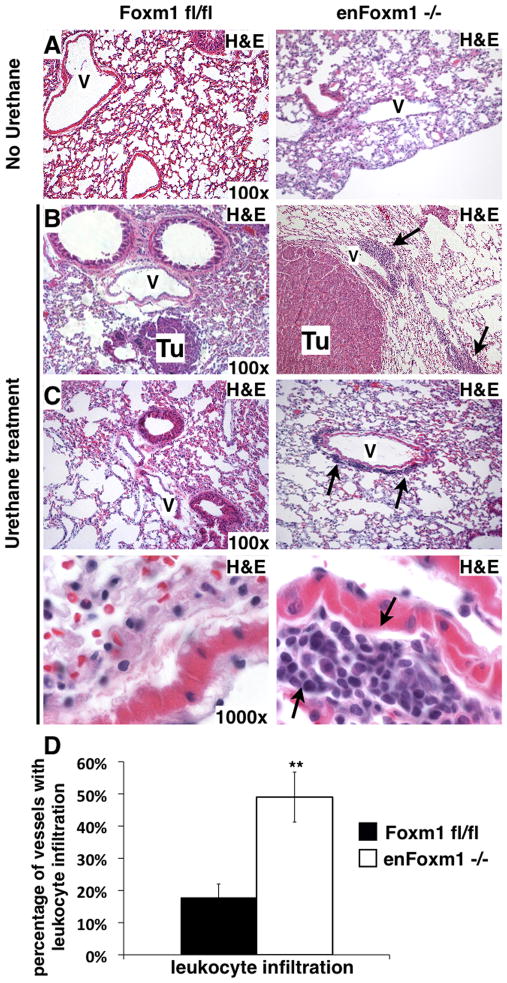

Figure 3. Increased perivascular leukocyte infiltration associates with increased tumor sizes in enFoxm1−/− mice.

A. H&E staining of lungs from enFoxm1−/− and control Foxm1fl/fl mice 30 weeks after urethane treatment. Lung inflammation was not observed in untreated enFoxm1 −/− or control mice. B-C. Increased infiltration of inflammatory cells around bigger tumors (Tu) and vessels in enFoxm1−/− lungs 30 weeks after urethane treatment. Perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells is shown with arrows. Higher magnification of the representative vessels from control and enFoxm1−/− lungs shown in bottom panels. V – blood vessel. Magnifications: panels A-C, 100x; bottom panels in C, 1000x. D. Percentage of vessels exhibiting leukocyte infiltration was determined in ten random microscope fields and presented as mean + SD.

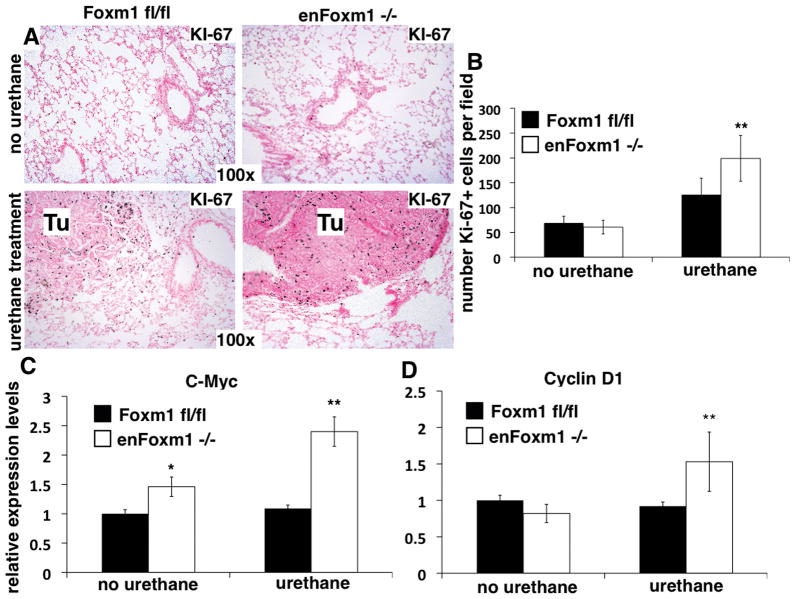

Proliferation of tumor cells in enFoxm1−/− lungs is increased

Immunohistochemical staining with proliferation specific Ki-67 antibodies showed no significant differences in the cellular proliferation between untreated control and enFoxm1−/− lungs (Fig. 2A and 2B). However, 30 weeks after urethane treatment, numbers of Ki-67-positive cells in enFoxm1−/− tumors were significantly increased (Fig. 2B), which is consistent with increased tumor sizes in these mice (Fig. 1C). Moreover, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of c-Myc and Cyclin D1, known markers of proliferating cells, were significantly increased in lungs from enFoxm1−/− mice compared to control mice (Fig. 2C and 2D). Thus, increased tumor formation in enFoxm1−/−lungs resulted from increased proliferation.

Figure 2. Increased proliferation of tumor cells in enFoxm1−/− lungs.

enFoxm1−/− and control Foxm1fl/fl lungs were harvested 30 weeks after initial urethane injection and used for immunohistochemistry with Ki-67 antibodies or to isolate total lung mRNA for qRT-PCR. A. Increased proliferation of tumor (Tu) cells in enFoxm1−/− lungs. B. enFoxm1−/− lungs have increased number of Ki-67-positive tumor cells compared to control mice. Ki-67-positive cells were counted in ten random microscope fields of control or enFoxm1−/− tumors. Increased mRNA levels of c-Myc (C) and Cyclin D1 (D) in enFoxm1−/− lungs after urethane treatment was demonstrated by qRT-PCR. β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. Magnifications: panels A, 100x. A p value <0.05 is shown with (*), a p value <0.01 is shown with(**).

Urethane induces chronic lung inflammation in enFoxm1−/− lungs

Conditional deletion of Foxm1 from endothelial cells did not influence the lung morphology and lung inflammation was not detected in untreated enFoxm1−/− mice (Fig. 3A), consistent with previously published studies (18). However, 30 weeks after urethane treatment, severe perivascular inflammation was observed in enFoxm1−/− mouse lungs, but not in the control lungs (Fig. 3B–D). Large tumors found in enFoxm1−/− lungs were generally located in close proximity to the blood vessels at sites of leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with previously published studies demonstrating that chronic inflammation promotes tumor growth (29).

Chronic lung inflammation in human patients is associated with the increased risk of lung cancer (30–31). Thus, we assessed the presence of inflammatory cells at the early stage of tumor induction with urethane. Mice were treated with 3 weekly injections of urethane and lungs were harvested 3 days after the last urethane injection. Increased focal inflammation was seen in the perivascular regions in enFoxm1−/− lungs compared to control lungs (Supplemental Fig. 2A–B and 2D), suggesting the increased inflammatory response to urethane treatment. These results were further supported by an increase in total number of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid from urethane-treated enFoxm1−/− mice compared to control mice (Supplemental Fig. 2C). No differences in the total number of BAL cells were observed in enFoxm1−/− and control mice without urethane treatment (Supplemental Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data demonstrated that urethane increased pulmonary inflammation in enFoxm1−/− mice, which was not resolved even by 30 weeks after urethane treatment.

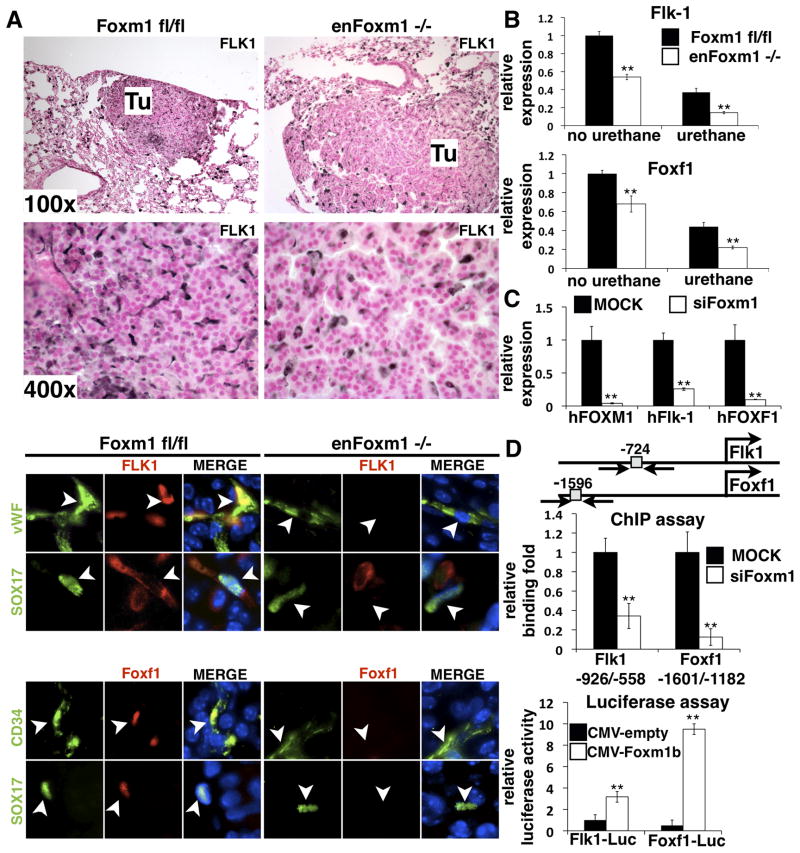

Decreased expression of Flk-1 and Foxf1 in enFoxm1−/− lungs

Since Foxm1 induces proliferation of endothelial cell during embryonic development and LPS lung injury (17–18), we examined if endothelial-specific deletion of Foxm1 influences tumor-mediated angiogenesis. PECAM-1 staining was not different in enFoxm1−/− and control tumors (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Likewise, qRT-PCR of the total lung RNA, showed no differences in PECAM-1 mRNA in enFoxm1−/− and control lungs (Supplemental Fig. 3B).

To identify potential Foxm1 targets, expression of several genes critical for lung inflammation and tumor formation was examined. While mRNA levels of VEGF-A, IL-6, TNFα, Lef and β-catenin were not influenced by Foxm1 deletion (supplemental Fig. 3D), Flk-1 (VEGFR2) mRNA and protein were decreased in enFoxm1−/− tumors (Fig. 4A top and 4B). The specific decrease of Flk-1 protein in Foxm1-deficient endothelial cells was shown by colocalization experiments using antibodies against endothelial-specific protein vWF or Sox-17 (Fig. 4A bottom panels), the latter of which is a transcription factor exclusively expressed in endothelial cells of adult lung (32). Interestingly, Foxm1 protein was not detected in endothelial cells of enFoxm1−/− tumors (supplemental Fig. 4A-B), confirming an efficient deletion of Foxm1 from endothelium. Furthermore, Foxf1 mRNA, encoding a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells (33-34), was significantly decreased in enFoxm1−/− lungs (Fig. 4B). Foxf1 protein was not detected in endothelial cells of enFoxm1−/− tumors as demonstrated by colocalization with CD34 or Sox17 antibodies (Fig. 4A bottom panels). Since deficiency of either Flk-1 or Foxf1 in mice was associated with severe lung injury and inflammation (35–38), the reduced expression of these genes may contribute to the increased inflammation seen in enFoxm1−/− lungs following urethane treatment. Interestingly, the decreased Flk-1 and Foxf1 mRNAs were also observed in enFoxm1−/− lungs prior to urethane treatment (Fig. 4B), suggesting that enFoxm1−/− mice are predisposed to pulmonary inflammation induced by urethane.

Figure 4. Decreased expression of Flk-1 and Foxf1 in enFoxm1−/− lungs and cultured endothelial cells.

A. enFoxm1−/− mice had decreased Flk1 protein levels in tumors (Tu) compared to control Foxm1fl/fl tumors (top panels). The decrease in Flk-1 and Foxf1 protein levels in enFoxm1−/− tumors was specific to endothelial cells (bottom panels). Immunostaining was performed using antibodies against Flk-1 (red) and either endothelial specific vWF or Sox17 (green). Endothelial specific CD34 or Sox17 (green) antibodies were used to co-localize with Foxf1 (red). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Arrowheads indicate endothelial cells. B. enFoxm1−/− mice showed decreased Flk1 and Foxf1 mRNAs either prior to or after urethane treatment. qRT-PCR was performed using total lung RNA from either untreated mice or mice harvested 30 weeks after urethane treatment. Mouse β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. C. Foxm1 depletion in HMVEC-L cells reduced Flk-1 and Foxf1 mRNA expression. HMVEC-L human endothelial cells were mock transfected (MOCK) or transfected with short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex specific for Foxm1 mRNA (siFoxm1). Human β-actin mRNA was used for normalization. D. Flk-1 and Foxf1 are direct transcriptional targets of Foxm1. A schematic drawing of promoter regions of the mouse Flk-1 and Foxf1 genes. Locations of potential Foxm1 DNA binding sites are indicated (grey boxes). ChIP assay demonstrated that Foxm1 protein binds to promoter regions of Flk-1 and Foxf1 genes. Foxm1 binding to genomic DNA was normalized to IgG control antibodies. Diminished binding of Foxm1 to the endogenous mouse promoter regions of the Flk-1 and Foxf1 genes was observed after siFoxm1 transfection in MFLM-91U endothelial cells. Luciferase assay demonstrated that Foxm1 induced the transcriptional activity of Flk-1 and Foxf1 promoters. MFLM-91U cells were transfected with CMV-Foxm1b expression vector and luciferase (LUC) reporter driven by either -1.5kb mouse Flk-1 or -2.7kb mouse Foxf1 promoter regions. CMV-empty plasmid was used as a negative control. Cells were harvested at 24 hr after transfection and processed for dual LUC assays to determine LUC activity. Transcriptional activity of the mouse Flk-1 and Foxf1 promoters was increased by CMV-Foxm1b transfection. Magnifications: top panels in A, 100x; middle panels, 400x; bottom panels, 1000x. A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*).

Foxm1 directly induces transcriptional activity of Flk-1 and Foxf1 promoters

Decreased expression of Flk-1 and Foxf1 in enFoxm1−/− lungs suggests that these genes are targets of Foxm1. To determine whether Foxm1 regulates expression of these genes in vitro, HMVEC-L human endothelial cells were transfected with short interfering RNA (siRNA) specific to the human Foxm1 mRNA (siFoxm1) or with mutant siFoxm1, containing 5 mutations in recognition sequence (9). Seventy-two hours after siRNA transfection, total RNA was prepared from the HMVEC-L cells and analyzed for Foxm1 expression by qRT-PCR. siFoxm1 transfection efficiently reduced Foxm1 mRNA (Fig. 4C). Consistent with our in vivo studies (Fig. 4A), Foxm1-depletion in cultured endothelial cells significantly decreased Flk-1 and Foxf1 mRNAs (Fig. 4C).

Since Foxm1 deficiency was associated with decreased Flk-1 and Foxf1 expression in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 4A–C), we investigated whether Foxm1 transcriptionally activated promoter regions of these genes. The potential Foxm1 DNA binding sites were identified in the −1.5Kb promoter region of the mouse Flk-1 gene and −2.7Kb promoter region of the mouse Foxf1 gene (Fig. 4D). Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were used to determine whether Foxm1 protein directly binds to the promoter regions of these two genes in mouse MFLM-91U endothelial cells. Foxm1 protein specifically bound to both the Flk-1 and Foxf1 promoter regions as demonstrated by the ability of siFoxm1 to reduce binding of Foxm1 protein to the promoter DNA (Fig. 4D, left panel). To determine whether the Foxm1-binding sites were transcriptionally active, co-transfection experiments were performed using CMV-Foxm1b expression vector (17) and luciferase (LUC) reporter constructs driven by either Flk-1 or Foxf1 promoter regions. Co-transfection of the CMV-Foxm1b expression vector significantly increased activity of both reporters when compared to CMV-empty vector (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that Foxm1 directly binds to and transcriptionally activates the mouse Flk-1 and Foxf1 promoter regions, indicating that these endothelial genes are direct Foxm1 targets.

Canonical Wnt signaling is increased in enFoxm1−/− lungs after urethane treatment

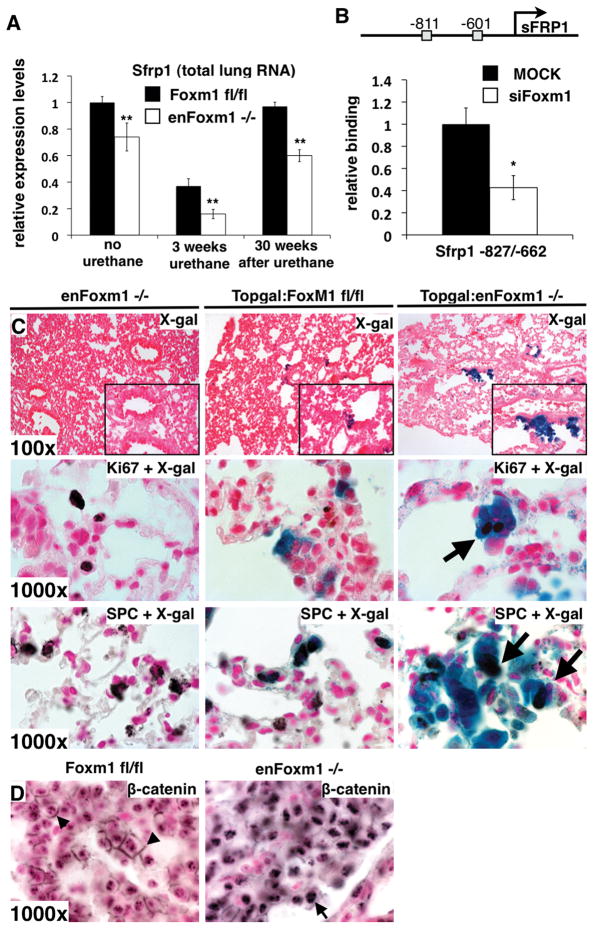

Since deletion of Foxm1 from endothelial cells caused increased proliferation of tumor cells following urethane injury (Fig. 2B), we focused on molecular mechanisms involved in the cross talk between epithelial and endothelial cells in enFoxm1−/− lungs. Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 (Sfrp1) mRNA, a Wnt signaling inhibitor, was significantly decreased in enFoxm1−/− lungs at 3 and 30 weeks after urethane treatment (Fig. 5A). Diminished expression of Sfrp1 was also found in lungs of untreated enFoxm1−/− mice (Fig. 5A), coinciding with decreased Foxm1 mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). Since, two potential Foxm1 DNA binding sites were identified in the – 1.0Kb promoter region of the mouse Sfrp1 gene (Fig. 5B), we used ChIP assay to determine whether Foxm1 protein directly binds to the mouse Sfrp1 promoter. Foxm1 specifically bound to the mouse Sfrp1 promoter region as demonstrated by the ability of siFoxm1 to reduce binding of Foxm1 protein to the Sfrp1 promoter DNA (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Canonical Wnt signaling is activated in enFoxm1−/− lung epithelial cells after urethane treatment.

A. Sfrp1 mRNA is decreased in enFoxm1−/− lungs. B. A schematic drawing of the – 1.0Kb promoter regions of the mouse Sfrp1 gene. Locations of two potential Foxm1 DNA binding sites are indicated (grey boxes). ChIP assay demonstrated that Foxm1 protein binds to promoter of mouse Sfrp1 gene. Foxm1 binding to genomic DNA was normalized to IgG control antibodies. Diminished binding of Foxm1 to the Sfrp1 promoter region was observed after siFoxm1 transfection in MFLM-91U. C. enFoxm1−/−/TOPGAL mice had increased β-gal activity in epithelial cells compared to Foxm1fl/fl/TOPGAL mice (top panels). Immunohistochemistry with Ki-67 antibodies onβ-gal stained lung sections shows the presence of Ki-67 protein (arrows) in β-gal-positive cells in enFoxm1−/− mice (middle panels). Immunohistochemistry with pro-SPC antibodies on β-gal stained lung sections shows that pro-SPC co-localized with β-gal in subset of epithelial cells (arrows in bottom panels:). D. Increased nuclear localization of β-catenin in enFoxm1−/− tumors. Membrane β-catenin staining in control Foxm1fl/fl tumors shown with arrows. Magnifications: top panels in C, 100x; inserts, 400x; middle and bottom panels in C and D, 1000x. A p value < 0.05 is shown with asterisk (*), a p value < 0.01 is shown with asterisk (**).

Decreased activity of Sfrp1 was associated with activation of canonical Wnt signaling in the lung (39). To assess canonical Wnt signaling, enFoxm1−/− mice were bred with TOPGAL transgenic mice that are frequently used as in vivo reporter for canonical Wnt activity (22). enFoxm1−/−/TOPGAL mice and control Foxm1fl/fl/TOPGAL or enFoxm1−/− mice were treated with 6 weekly injections of urethane. Increased TOPGAL activity was observed in hyperplastic epithelial regions of enFoxm1−/− mice during initial stages of lung tumorigenesis (Fig. 5C, top panels). Type II lung epithelial cells expressing pro-SPC were frequently found in regions with increased TOPGAL activity (Fig. 5C, bottom panels). Likewise, Ki-67 was frequently co-localized with β-gal in enFoxm1−/−/TOPGAL lungs (Fig. 5C, middle panels), indicating increased proliferation rates in enFoxm1−/− epithelium. Finally, consistent with increased canonical Wnt signaling, the increase in nuclear localization of β-catenin was detected in enFoxm1−/− tumors (Fig. 5D). Thus, Foxm1 deletion from endothelial cells led to the decreased expression of the Wnt inhibitor, Sfrp1, causing activation of canonical Wnt signaling and increased proliferation of epithelial cells.

Discussion

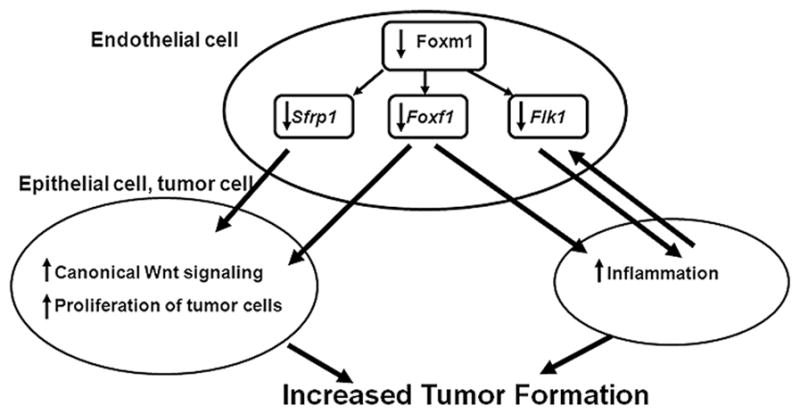

While Foxm1 is known as a proliferation specific transcription factor, recent studies suggest the importance of Foxm1 in other cellular functions, including cell migration, invasiveness, vascular permeability, angiogenesis, surfactant homeostasis, oxidative stress and inflammation (16–18, 25, 40–43). The significance of the work presented here is the finding that Foxm1 is involved in the cross-talk between endothelial cells and other respiratory cell types during formation of lung cancer (Figure 6). Foxm1 expression in endothelial cells is critical for proliferation of lung tumor cells via regulation of canonical Wnt signaling (through Sfrp1 and Foxf1) and pulmonary inflammation (through Flk-1 and Foxf1).

Figure 6. Role of Foxm1 in the cross-talk between endothelial and epithelial cells during lung tumorigenesis.

After Foxm1 deletion from endothelial cells, expression of Flk-1, Foxf1 and Sfrp1 is decreased. These endothelial genes are direct Foxm1 targets. Decreased Flk-1 and Foxf1 expression promotes chronic lung inflammation in enFoxm1−/− lungs. Decreased Sfrp1 and Foxf1 expression causes activation of canonical Wnt signaling in respiratory epithelium. Chronic lung inflammation and Wnt-induced epithelial proliferation promote lung tumorigenesis in enFoxm1−/− mice.

Foxm1 is ubiquitously expressed in proliferating cells of different origin and is known to play a critical role in cell cycle progression by directly activating transcription of cell cycle regulatory genes such as Cdc25B, cyclin B1, Aurora B Kinase and Polo-like Kinase 1 (5–6). Previous studies demonstrated that Foxm1-deficiency caused decreased proliferation of endothelial cells during lung development (17) and during acute lung injury induced by inflammatory mediator, LPS (18). Thus, Foxm1 is critical for proliferation of endothelial cells and may contribute to vessel formation in cancer lesions. Surprisingly, in spite of Foxm1 deficiency in endothelial cells, enFoxm1−/− mice developed increased number of lung tumors after urethane exposure. While lungs of untreated enFoxm1−/− mice had normal morphology, urethane treatment caused severe pulmonary inflammation, which was characterized by perivascular infiltration of inflammatory cells and increased numbers of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid. The direct relationship between inflammation and cancer is widely accepted: inflammation promotes tumor growth (29). Therefore, increased numbers of lung tumors in enFoxm1−/− mice may be a consequence of persistent pulmonary inflammation after urethane exposure. Interestingly, enFoxm1−/− mice exhibited impaired endothelial cell repair, and increased vascular permeability following acute lung injury with LPS (18). Decreased vascular repair after urethane treatment may contribute to augmented lung inflammation and increased tumorigenesis in enFoxm1−/− mice.

We found that Flk-1 protein and mRNA in the enFoxm1−/− lungs were decreased. The decline in pulmonary expression of Flk-1 in aged humans and animals was associated with more severe lung injury, increased inflammation and higher mortality (38). Decreased Flk-1 expression was found in patients with broncho-pulmonary dysplasia, a chronic lung injury that is associated with persistent pulmonary inflammation (44). Consistent with these studies, reduced Flk-1 expression in urethane-treated enFoxm1−/− lungs may promote pulmonary inflammation. We also found that expression of Forkhead protein, Foxf1, was decreased in enFoxm1−/−endothelial cells. Haploinsufficiency of Foxf1 gene in mice caused abnormal lung capillary development and pulmonary edema (36–37). Inactivating mutations or deletions in FOXF1 gene locus were found in human patients with alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV), a devastating developmental disorder with mortality rate 100% in the first months of life (45). Foxf1-deficiency caused increased pulmonary inflammation after chemically-induced or allergen-mediated lung injury, indicating an important role of Foxf1 in the pathogenesis of pulmonary inflammation (20, 36). Thus, the increased lung inflammation in urethane-treated enFoxm1−/− lungs could be a consequence of decreased Foxf1 expression. An important contribution of the present study is demonstration that both Flk-1 and Foxf1 genes are direct targets of Foxm1. Thus, Foxm1 is likely to regulate lung inflammation by inducing expression of Flk-1 and Foxf1 in endothelial cells.

Since endothelial-specific disruption of Foxm1 increased proliferation of epithelial-derived tumor cells, we focused on molecular pathways involved in the cross-talk between endothelial and epithelial cells during tumor formation. Sfrp1, a known inhibitor of the canonical Wnt signaling, was decreased in enFoxm1−/− lungs. Originally identified as a developmentally active pathway, the canonical Wnt pathway has recently been linked to the pathogenesis of lung cancer, NSCLC in particular (46). The Wnt inhibitors, Sfrp1, WIF and DKK3, were shown to be decreased in NSCLC (47–48). In the present study, we demonstrated that deletion of Foxm1 in endothelial cells in vivo and in vitro reduced Sfrp1 mRNA. Foxm1 specifically binds to the Sfrp1 promoter region, indicating that Sfrp1 gene is a direct target of Foxm1. Moreover, we provided evidence that Wnt signaling is activated in enFoxm1−/− respiratory epithelial cells, which could be a direct consequence of decreased inhibition by Sfrp1. We also found an increase in epithelial proliferation in enFoxm1−/− lungs, a finding consistent with previous studies that canonical Wnt signaling induces cellular proliferation and expression of genes critical for the cell cycle progression (49). Since the pivotal role of Wnt activation in cancer has been already established (46), increased Wnt signaling in enFoxm1−/− lungs may contribute to aberrant proliferation of lung epithelial cells and increased tumor formation. Interestingly, Foxf1 transcription factor was down-regulated in enFoxm1−/− lungs and in Foxm1-depleted cultured endothelial cells. Recent studies demonstrated that Foxf1 controls proliferation of epithelial cells by limiting mesenchymal to epithelial signaling during gut development (50). The loss of Foxf1 from intestinal mesenchymal cells increased canonical Wnt signaling and led to hyperproliferation of intestinal epithelium (50). Therefore, the decreased expression of Foxf1 in enFoxm1−/− lungs could contribute to the activation of Wnt signaling and induction of epithelial proliferation.

Taken together, our data suggest that increased tumorigenesis in enFoxm1−/− mice is the result of increased lung inflammation and activation of canonical Wnt signaling, both of which are known to promote tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: American Cancer Society, Ohio Division (TVK), the Concern Foundation 84794 (TVK), a DOD New Investigator Award PC080478 (TVK), NIH grants R01 CA142724 (TVK) and R01 HL 84151 (VVK), and Research Scholar Grant RSG-06-187-01 from the American Cancer Society, National office (VVK).

Abbreviations

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- Cre

Cre recombinase

- Fox

Forkhead Box transcription factor

- Sfrp1

Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 1

References

- 1.Clevidence DE, Overdier DG, Tao W, et al. Identification of nine tissue-specific transcription factors of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/forkhead DNA-binding-domain family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3948–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaestner KH, Lee KH, Schlondorff J, Hiemisch H, Monaghan AP, Schutz G. Six members of the mouse forkhead gene family are developmentally regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7628–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korver W, Roose J, Clevers H. The winged-helix transcription factor Trident is expressed in cycling cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1715–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.9.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye H, Kelly TF, Samadani U, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/fork head homolog 11 is expressed in proliferating epithelial and mesenchymal cells of embryonic and adult tissues. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1626–41. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalinichenko VV, Major M, Wang X, et al. Forkhead Box m1b Transcription Factor is Essential for Development of Hepatocellular Carcinomas and is Negatively Regulated by the p19ARF Tumor Suppressor. Genes & development. 2004;18:830–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang IC, Chen YJ, Hughes D, et al. Forkhead box M1 regulates the transcriptional network of genes essential for mitotic progression and genes encoding the SCF (Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10875–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10875-10894.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Major ML, Raychaudhuri P. New and unexpected: forkhead meets ARF. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2005;15:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myatt SS, Lam EW. The emerging roles of forkhead box (Fox) proteins in cancer. Nature reviews. 2007;7:847–59. doi: 10.1038/nrc2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalin TV, Wang IC, Ackerson TJ, et al. Increased levels of the FoxM1 transcription factor accelerate development and progression of prostate carcinomas in both TRAMP and LADY transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1712–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang IC, Meliton L, Tretiakova M, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Kalin TV. Transgenic expression of the forkhead box M1 transcription factor induces formation of lung tumors. Oncogene. 2008;27:4137–49. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang IC, Meliton L, Ren X, et al. Deletion of Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor from respiratory epithelial cells inhibits pulmonary tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makrilia N, Lappa T, Xyla V, Nikolaidis I, Syrigos K. The role of angiogenesis in solid tumours: an overview. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:669–76. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Zhang N, Dai B, et al. FoxM1B transcriptionally regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression and promotes the angiogenesis and growth of glioma cells. Cancer research. 2008;68:8733–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim IM, Ramakrishna S, Gusarova GA, Yoder HM, Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV. The forkhead box M1 transcription factor is essential for embryonic development of pulmonary vasculature. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:22278–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao YY, Gao XP, Zhao YD, et al. Endothelial cell-restricted disruption of FoxM1 impairs endothelial repair following LPS-induced vascular injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2333–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI27154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupczak-Hollis K, Wang X, Kalinichenko VV, et al. The Mouse Forkhead Box m1 Transcription Factor is Essential for Hepatoblast Mitosis and Development of Intrahepatic Bile Ducts and Vessels during Liver Morphogenesis. Developmental biology. 2004;276:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalin TV, Meliton L, Meliton AY, Zhu X, Whitsett JA, Kalinichenko VV. Pulmonary mastocytosis and enhanced lung inflammation in mice heterozygous null for the Foxf1 gene. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2008;39:390–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0044OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ustiyan V, Wang IC, Ren X, et al. Forkhead box M1 transcriptional factor is required for smooth muscle cells during embryonic development of blood vessels and esophagus. Developmental biology. 2009;336:266–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akeson AL, Wetzel B, Thompson FY, et al. Embryonic vasculogenesis by endothelial precursor cells derived from lung mesenchyme. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:11–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200001)217:1<11::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim IM, Zhou Y, Ramakrishna S, et al. Functional characterization of evolutionarily conserved DNA regions in forkhead box f1 gene locus. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:37908–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalin TV, Wang IC, Meliton L, et al. Forkhead Box m1 transcription factor is required for perinatal lung function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:19330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806748105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holzinger A, Dingle S, Bejarano PA, et al. Monoclonal antibody to thyroid transcription factor-1: production, characterization, and usefulness in tumor diagnosis. Hybridoma. 1996;15:49–53. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1996.15.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borczuk AC, Gorenstein L, Walter KL, Assaad AA, Wang L, Powell CA. Non-small-cell lung cancer molecular signatures recapitulate lung developmental pathways. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163:1949–60. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malkinson AM, Koski KM, Evans WA, Festing MF. Butylated hydroxytoluene exposure is necessary to induce lung tumors in BALB mice treated with 3-methylcholanthrene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2832–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody JS, Spira A. State of the art. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammation, and lung cancer. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:535–7. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-089MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaturvedi AK, Caporaso NE, Katki HA, et al. C-Reactive Protein and Risk of Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange AW, Keiser AR, Wells JM, Zorn AM, Whitsett JA. Sox17 promotes cell cycle progression and inhibits TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling to initiate progenitor cell behavior in the respiratory epithelium. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa RH, Kalinichenko VV, Lim L. Transcription Factors in Mouse Lung Development and Function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L823–L38. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.5.L823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalinichenko VV, Zhou Y, Bhattacharyya D, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the Mouse Forkhead Box f1 Gene Causes Defects in Gall Bladder Development. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:12369–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su X, Taniuchi N, Jin E, et al. Spatial and phenotypic characterization of vascular remodeling in a mouse model of asthma. Pathobiology. 2008;75:42–56. doi: 10.1159/000113794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalinichenko VV, Zhou Y, Shin B, et al. Wild Type Levels of the Mouse Forkhead Box f1 Gene are Essential for Lung Repair. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L1253–L65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalinichenko VV, Lim L, Shin B, Costa RH. Differential Expression of Forkhead Box Transcription Factors Following Butylated Hydroxytoluene Lung Injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280:L695–L704. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.4.L695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ito Y, Betsuyaku T, Nagai K, Nasuhara Y, Nishimura M. Expression of pulmonary VEGF family declines with age and is further down-regulated in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced lung injury. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawano Y, Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. Journal of cell science. 2003;116:2627–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang IC, Chen YJ, Hughes DE, et al. FoxM1 regulates transcription of JNK1 to promote the G1/S transition and tumor cell invasiveness. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:20770–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709892200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park HJ, Carr JR, Wang Z, et al. FoxM1, a critical regulator of oxidative stress during oncogenesis. EMBO J. 2009;28:2908–18. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Z, Banerjee S, Kong D, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Forkhead Box M1 transcription factor leads to the inhibition of invasion and angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:8293–300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Q, Zhang N, Jia Z, et al. Critical role and regulation of transcription factor FoxM1 in human gastric cancer angiogenesis and progression. Cancer research. 2009;69:3501–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1723–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stankiewicz P, Sen P, Bhatt SS, et al. Genomic and genic deletions of the FOX gene cluster on 16q24.1 and inactivating mutations of FOXF1 cause alveolar capillary dysplasia and other malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul S, Dey A. Wnt signaling and cancer development: therapeutic implication. Neoplasma. 2008;55:165–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukui T, Kondo M, Ito G, et al. Transcriptional silencing of secreted frizzled related protein 1 (SFRP 1) by promoter hypermethylation in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:6323–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Licchesi JD, Westra WH, Hooker CM, Machida EO, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Epigenetic alteration of Wnt pathway antagonists in progressive glandular neoplasia of the lung. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:895–904. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A. Wnt signalling and the control of cellular metabolism. Biochem J. 2010;427:1–17. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ormestad M, Astorga J, Landgren H, et al. Foxf1 and Foxf2 control murine gut development by limiting mesenchymal Wnt signaling and promoting extracellular matrix production. Development. 2006;133:833–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.02252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.