Abstract

Ca2+ homeostasis plays a critical role in a variety of cellular processes. We showed previously that stimulation of the prostate-specific G protein-coupled receptor (PSGR) enhances cytosolic Ca2+ and inhibits proliferation of prostate cells. Here, we analyzed the signaling mechanisms underlying the PSGR-mediated Ca2+ increase. Using complementary molecular, biochemical, electrophysiological, and live-cell imaging techniques, we found that endogenous Ca2+-selective transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 (TRPV6) channels are critically involved in the PSGR-induced Ca2+ signal. Biophysical characterization of the current activated by PSGR stimulation revealed characteristic properties of TRPV6. The molecular identity of the involved channel was confirmed using RNA interference targeting TrpV6. TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ influx depended on Src kinase activity. Src kinase activation occurred independently of G protein activation, presumably by direct interaction with PSGR. Taken together, we report that endogenous TRPV6 channels are activated downstream of a G protein-coupled receptor and present the first physiological characterization of these channels in situ.

Keywords: Calcium, G Protein-coupled Receptor (GPCR), Signal Transduction, Src, TRP Channels

Introduction

Ca2+ ions function as ubiquitous second messengers that control a variety of cellular processes such as differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (1). Epithelial cells control their cytosolic Ca2+ level via non-voltage-gated plasma membrane cationic channels and/or depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores followed by Ca2+ entry via store-operated channels. Several plasma membrane channels have been implicated in modulation of cytosolic Ca2+ in prostate epithelial cells (2–6). Notably, the two highly Ca2+-selective Ca2+ (re)absorption channels TRPV53 and TRPV6 were found to be expressed in prostate cells (7–9). TRPV6 has been proposed to play a role in prostate cancer cell proliferation (9, 10). The biophysical characteristics of recombinantly overexpressed TRPV6 channels have been studied intensively (11). However, no information on channel physiology in native cells is available. Overexpression of TRPV6 leads to constitutively open channels, and so far no activation mechanism has been described (12).

We previously reported that activation of PSGR by β-ionone induces an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and a decreased proliferation rate of prostate cancer cells (13). Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine the mechanism of Ca2+ entry into prostate epithelial cells upon stimulation of PSGR, a class A GPCR that was initially identified as a prostate-specific tumor biomarker (14). Here, we identified TRPV6 as an important signaling protein downstream of activated PSGR showing that TRPV6 can function as a receptor-operated channel. We further identified the tyrosine kinase Src as a signaling protein coupling PSGR and TRPV6 independently of G proteins. In this context, we present the first electrophysiological analysis of endogenous TRPV6 channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Transfection

LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum superior and 100 units/ml penicillin and streptomycin. For siRNA experiments, cells were co-transfected with siRNA (Ambion) and a pIRES2-EGFP vector (Clontech) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Alternatively, expression vector-based siRNA was transfected using Exgen 500 (Fermentas). 2 days after transfection, cells were used for experiments.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed by standard procedures. Quantification was done using the Pharos Fx Plus Molecular Imager system (Bio-Rad) (for details, see supplemental Methods).

siRNA Constructs and Plasmids

Target and negative control TrpV6 siRNA 1 (s30900) were bought from Ambion (Silencer® Select Pre-designed siRNA). TrpV6-targeted and scrambled hairpin siRNA 2 designs were carried out with siRNA Target Designer Version 1.51 (Promega); oligonucleotides were synthesized by Invitrogen and ligated into the pGeneClipTM hMGFP vector (Promega) (for details, see supplementary Methods).

To create a vector encoding GST-PSGR-C terminus, the C terminus of PSGR (amino acids 293–320) was amplified by PCR from a plasmid containing the full-length receptor (13) and ligated into pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences) (for details, see supplemental Methods).

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative PCR experiments were performed using predeveloped TaqMan assay reagents and TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Ambion) for TrpV6 (HS00367960m1) and an iQ5 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. GAPDH (4333764T) was used to normalize the amount of TrpV6 mRNA in the different cDNA populations tested. The quantitative PCR procedure was repeated three times in independent runs, and the expression levels were calculated by applying the CtΔΔ method.

Protein Purification and in Vitro Binding

Bacterial expression and preparation of GST fusion proteins were performed according to standard procedures. For the interaction assay, the GST fusion protein and GST alone (control) bound to glutathione-Sepharose were incubated with 2.5 μg of recombinant Src kinase (Biaffin) in binding buffer at 4 °C overnight. After washing, samples were loaded on polyacrylamide gels, and Western blotting with anti-Src antibody was performed.

Electrophysiology

Patch clamp experiments were conducted in the whole cell patch clamp configuration using an EPC-9 or EPC-10 amplifier controlled by Pulse or Patchmaster software (HEKA Electronics). Patch pipettes (4–6 megohms) were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.5-mm outer diameter/0.86-mm inner diameter; Science Products) and fire polished using a horizontal pipette puller (Zeitz Instruments) or a PC-10 vertical micropipette puller and a MF-830 Microforge (Narishige Instruments). During experiments, cells were superfused with extracellular recording solution (ERS). A microcapillary application system was used for solution changes and drug/odorant application. An agar bridge containing 150 mm KCl connected the reference electrode with the bath solution. Immediately after establishing the whole cell configuration, voltage ramps of 50-ms duration from −100 mV to +100 mV were delivered from a holding potential of −10 mV at a rate of 0.5 Hz. The capacitance and the series resistance were compensated before each ramp using the automatic compensation procedures of the amplifier. Cells with a series resistance >12 megohms were discarded. Immediately after break in, voltage ramp recordings showed an outward current at positive potentials that was gradually inhibited by tetraethylammonium. This background current was similar in all cells (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). The tetraethylammonium-inhibited current was subtracted from all subsequent current records (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Current amplitudes were measured in background-corrected individual ramp recordings at −80 mV (in some experiments also at +80 mV) and plotted over time. Currents were normalized by dividing the amplitude by the cell capacitance.

Single-cell Ca2+ Imaging

LNCaP cells plated on glass were incubated for 45 min at 37 °C in standard extracellular solution containing 3 μm fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes). Ratiofluorometric Ca2+ imaging was performed in standard extracellular solution using a Zeiss inverted microscope equipped for ratiometric imaging and a Polychrome V monochromator (TILL Photonics). Images were acquired at 0.5 Hz, and integrated fluorescence ratios (F340/F380) were measured using TILLvisION software (TILL Photonics). Cells were visualized with a 100 × oil immersion objective (UPLSAPO, Olympus). Due to the high magnification only one cell could be analyzed per experiment.

Chemicals and Solutions

Solutions used in Ca2+ imaging experiments were standard extracellular solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 0.3 mm Na2HPO4, 0.4 mm KH2PO4, 4 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3 (NaOH), adjusted to 325 mOsm (glucose) and Ca2+-free extracellular standard solution containing 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 10 mm EGTA, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.3 mm Na2HPO4, 0.4 mm KH2PO4, 4 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3 (NaOH), 325 mOsm (glucose).

In electrophysiological experiments, the standard intracellular (pipette) solution contained 133 mm Cs methanesulfonate, 7 mm CsCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, 10 mm EGTA, 2 mm MgATP, 1 mm Na2GTP, pH 7.1 (CsOH), 315 mOsm (glucose). Cells were kept in standard extracellular solution, but during experiments cells were superfused with ERS containing 100 mm NaCl, 45 mm tetraethylammonium chloride, 10 mm CsCl, 10 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3, 325 mOsm (glucose). For a detailed description of further solutions and chemicals, see supplemental Methods.

Data Analysis

Electrophysiological and Ca2+ imaging data were analyzed using IGOR PRO software (Wavemetrics). Student's t test was used for measuring the significance of difference between two distributions. If not otherwise stated, data are given as means ± S.E. for n number of cells.

RESULTS

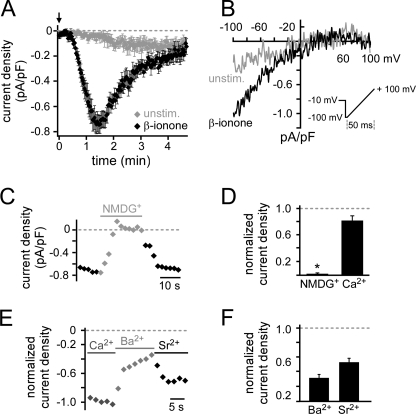

PSGR Activation Triggers Opening of a Plasma Membrane Cationic Channel

To elucidate the signaling mechanisms underlying the PSGR-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase, we used LNCaP cells, a prostate cancer cell line expressing PSGR (14). To investigate the role of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels, we monitored the membrane current by measuring I-V curves at a rate of 0.5 Hz in whole cell patch clamp experiments (Fig. 1B inset). Without stimulation a very small current developed after a long delay (88.8 ± 17.1 s, Imax = −0.16 ± 0.05 pA/pF). However, when challenging LNCaP cells with β-ionone directly after establishing the whole cell configuration, a significantly different current with a characteristic time course developed with a short delay (37.6 ± 3.5 s, Imax = −0.86 ± 0.07 pA/pF) (Fig. 1, A and B). After reaching a maximum, the current decayed with a time constant τ of 53.9 ± 3.1 s to 23.5% of the maximal current (Imax). The I-V relationship revealed strong inward rectification and almost no outward current at positive membrane potentials. We recorded this macroscopic current in 70% of all cells tested (n = 119/171), whereas the remaining cells showed a greatly reduced current undistinguishable from the current measured in unstimulated cells (Fig. 1, A and B). By replacing all extracellular cations with NMDG+, the β-ionone-induced current was completely abolished. However, it was only slightly reduced when all extracellular cations but Ca2+ (10 mm) were replaced (Fig. 1, C and D, and supplemental Fig. S1, C–E), suggesting a high selectivity for Ca2+ ions. In presence of Sr2+ and Ba2+, we observed a smaller current than in equimolar Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 1, E and F). Despite this difference in amplitude, the time course of the Sr2+ current was similar to the one observed in ERS (supplemental Fig. S1F). Current characteristics are summarized in supplemental Table S1. Expecting an activation of highly Ca2+-permeable channels, we usually buffered the intracellular Ca2+ concentration with 10 mm EGTA to prevent potential Ca2+-dependent channel inhibition. In experiments using only 0.5 mm EGTA (low buffering solution) we did not observe any β-ionone-induced current (supplemental Fig. S1G). PSGR activation by β-ionone in LNCaP cells therefore triggers opening of a plasma membrane Ca2+-conducting cation channel.

FIGURE 1.

β-Ionone stimulation activates Ca2+-permeable cation channels in LNCaP cells. A, mean whole cell current with two-sided scanning electron microscope was plotted over time. Current amplitudes at −80 mV were obtained from individual voltage ramp recordings shown in B and normalized to the cell capacitance. Ramps were performed every 2 s, the holding potential was −10 mV, recordings were performed in ERS. 500 μm β-ionone was applied directly after break-in (indicated by arrow) and induced a current (black) with characteristic time course in 70% of stimulated cells. Shown is the mean current of responding cells. It increased slowly to a maximum (τ = 34.0 ± 3.9 s) and then decayed (τ = 59.2 ± 4.0 s, Iresidual = −0.2 ± 0.03 pA/pF, n = 13). The very small current observed in unstimulated cells (gray) was significantly different in delay (88.8 ± 17.1 s, p < 0.001), rise time (τ = 76.3 ± 11.5 s, p < 0.001), maximal amplitude (Imax = −0.16 ± 0.05 pA/pF, p < 0.001), and decay (95.1% of Imax, Iresidual = −0.14 ± 0.05 pA/pF, p < 0.001, n = 9). B, representative I-V relationship was measured in single cells during β-ionone stimulation or under unstimulated control conditions in ERS. Currents were elicited by the voltage ramp shown in the inset. The background conductance measured at the experiment start was subtracted (see supplemental Fig. S1). C, replacing all extracellular cations by NMDG+ abolished the β-ionone-induced current (representative recording of single cell). D, mean current amplitude was significantly reduced when all extracellular cations were replaced by NMDG+ (Inorm = 0.02 ± 0.01, n = 5), but not when all cations but Ca2+ (10 mm) were replaced by NMDG+ (110 mm) (Inorm = 0.81 ± 0.07, n = 5). Current amplitudes were normalized to the current recorded in ERS before solution change. E, β-ionone-activated channels are permeable to Ca2+, Ba2+, and Sr2+ (representative recording of single cell). F, mean current amplitudes in the presence of Ba2+ (30 mm) and Sr2+ (30 mm) were normalized to the current measured in 30 mm Ca2+ (Inorm Sr2+ = 0.53 ± 0.05, n = 8 and Inorm Ba2+ = 0.32 ± 0.05, n = 10).

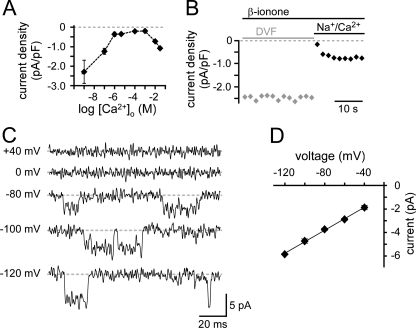

β-Ionone-induced Conductance Shares Properties of TRPV6 Channels

A preference for Ca2+ ions was confirmed by the anomalous mole fraction behavior observed in the presence of 100 mm extracellular Na+ and variable Ca2+ concentrations. The β-ionone-induced current densities strongly depended on the Ca2+ concentration (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S1H). When extracellular Ca2+ was strongly buffered with 5 mm EGTA or 10 mm EDTA (≤1 nm Ca2+, divalent-free (DVF)), the current density increased almost 3-fold. Thus, these channels showed an increased permeability for monovalent Na+ ions in the absence of divalent Ca2+ ions. Increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration from ≤1 nm to 1 mm blocked the monovalent current with an IC50 of ∼100 nm. Further elevation to 10 mm or 30 mm Ca2+ increased the current again. During a 30-s application of DVF solution, the β-ionone-induced current did not decay, but immediately declined when Ca2+ (10 mm) was added (Fig. 2B). This time course has been described for TRPV6 channels and is not typical for store-operated channels (15).

FIGURE 2.

β-Ionone-activated channels prefer Ca2+, but also conduct monovalent ions. A, β-ionone-activated channels show anomalous mole fraction behavior. Mean current with two-sided standard error of mean are plotted over various extracellular Ca2+ concentrations in the presence of 100 mm Na+ (n ≥ 5 for each concentration). In Ca2+-free highly buffered solution the Ca2+ concentration was ≤1 nm (DVF). B, in the presence of DVF solution (10 mm EGTA) the macroscopic β-ionone-induced current did not decay. Switching to ERS reduced the current immediately (representative recording of single cell). C, β-ionone-activated single-channel currents were recorded under DVF conditions at holding potentials indicated. These cells did not respond with macroscopic currents to β-ionone stimulation. D, linear I-V relationship of single-channel currents (mean ± S.E., n = 5) was plotted from −120 to −40 mV. Slope conductance was 49 pS.

In 30% of LNCaP cells, β-ionone could not induce a macroscopic current in ERS. However, when we switched to DVF solution we were able to record single-channel events at negative holding potentials in some of these cells. No channel openings were visible at membrane potentials ≥0 mV (Fig. 2C). The current amplitude increased with increasing negative membrane potentials. A linear regression fit yielded a slope conductance of 49 pS between −120 and −40 mV (n = 5) (Fig. 2D), matching the single-channel conductance reported for recombinant TRPV6 (16).

We next designed experiments to discriminate further between TRPV6 and store-operated channels. The β-ionone-induced current was strongly potentiated by application of 100 μm 2-APB (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). The potentiation occurred only at negative potentials and in both the early phase (0–10 s) and the late phase (20–30 s) of treatment. In the absence of β-ionone, 1-min application of 2-APB did not induce any current either at negative or at positive membrane potentials (n = 9) (Fig. 3, C and D). Thus, we can exclude an overlap of 2-APB-activated channels (e.g. Orai3) (17, 18). When we used thapsigargin to activate store-operated channels, the resulting current displayed an I-V relationship that was similar to the one induced by β-ionone (supplemental Fig. S2A). However, when we applied 100 μm 2-APB, the thapsigargin-induced current was potentiated in the early phase of the treatment, but strongly inhibited in the late phase (supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). To investigate further a possible involvement of store-operated channels in the β-ionone-induced response, we prevented store depletion by inhibition of inositol trisphosphate receptors using either xestospongin C or heparin. Neither treatment significantly changed the β-ionone-induced current characteristics or the response rate (supplemental Fig. S2, D–F). These results strongly suggest that store-operated channels are not involved in the β-ionone-induced current. We also investigated the dependence of the β-ionone-induced current on the membrane potential. When we increased the potential between ramp recordings from −10 mV to +50 mV, the β-ionone-induced current increased almost 2-fold (Inorm = 1.83 ± 0.1, n = 7) (Fig. 3, E and F). Current potentiation by both 2-APB and positive membrane potentials are consistent with and characteristic for TRPV6, but not store-operated channels (15, 19, 20). Together, these results suggest a PSGR-mediated activation of TRPV6 channels without substantial involvement of store-operated channels.

FIGURE 3.

β-Ionone-induced current is potentiated by 2-APB and positive membrane potential. A, I-V relationship of the β-ionone-induced current before and during application of 100 μm 2-APB (representative recording of single cell). B, temporal development of β-ionone-induced current amplitudes at −80 mV and at +80 mV before and during 2-APB application (representative recording of single cell). Amplitudes were obtained from ramp recordings performed every 2 s. C, stimulation with only 100 μm 2-APB did not induce a current (representative recording of single cell). D, mean current amplitudes during 2-APB application normalized to the current amplitude before 2-APB application. For β-ionone-induced currents, early and late 2-APB effects were analyzed. For the early 2-APB effect current amplitudes were obtained from the first five ramp recordings in the presence of 2-APB (0–10 s), whereas for the late effect the last five ramp recordings in the presence of 2-APB (20–30 s) were analyzed (n = 16). The current was significantly increased during early as well as late 2-APB application (both p ≤ 0.001). 2-APB alone did not activate a current (n = 9). E, temporal development of the β-ionone-induced current (obtained from ramp recordings at −80 mV) when the holding potential in between ramp recordings is raised from −10 mV to +50 mV (representative recording of single cell). F, Mean current amplitude measured when the holding potential is +50 mV normalized to the current obtained before the holding potential was changed (n = 6).

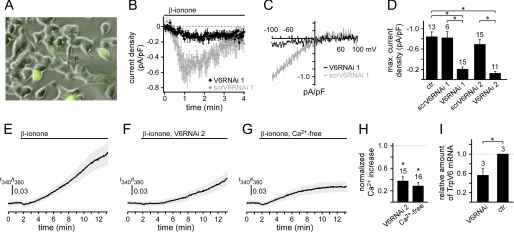

β-Ionone Stimulation Activates TRPV6 Channels in LNCaP Cells

To confirm that PSGR stimulation activates TRPV6 channels, we reduced the expression level of TrpV6 in two independent series of experiments using two different siRNAs. Co-transfection of the first target TrpV6 siRNA (V6RNAi 1) and EGFP was used to identify transfected cells (Fig. 4A). When GFP-expressing cells were challenged with β-ionone, none of the cells tested (n = 0/15) showed the typical response. Only a strongly reduced current developed (Imax = −0.21 ± 0.04 pA/pF) (Fig. 4, B–D). The maximal amplitude of this current was not significantly different from the one observed in unstimulated cells, but dramatically diminished compared with β-ionone-induced responses. Cells co-transfected with negative control TrpV6 siRNA (ctrV6RNAi) exhibited a β-ionone-induced current that was not significantly different from the current in untransfected cells (Fig. 4, B–D). The response rate was also similar (60%, n = 6/10). To validate the effect of siRNA against TrpV6, we performed TrpV6 expression analysis in RNAi-transfected LNCaP cells and found that the expression level was significantly reduced compared with control cells (p < 0.01, Fig. 4I). Because the transfection efficiency was approximately 60%, the nontransfected cells account for the residual TrpV6 transcripts. To control for the target specificity of the knockdown, we repeated the experiment using vector-based in vivo synthesis of TrpV6 si/shRNA with a different targeting sequence (V6RNAi 2) and GFP. Under these conditions, we obtained the same effect. Cells expressing V6siRNA 2 responded with a very small current to β-ionone stimulation (Imax = −0.13 ± 0.03 pA/pF, n = 11), whereas cells expressing scrambled TrpV6 siRNA showed typical β-ionone-induced currents with a similar response rate (61%, n = 17/28, Fig. 4D). We also stimulated cells expressing TrpV6 siRNA 2 with thapsigargin and observed no difference between transfected and untransfected cells (supplemental Fig. S3). Current features measured under the different experimental conditions are summarized in supplemental Table S1. As reported previously (8, 9, 21), transfecting cells with TrpV6 cDNA resulted in constitutive TRPV6 channel activity, which was potentiated by 2-APB (supplemental Fig. S5). Because overexpressed TRPV6 channels maintain an open state, we cannot show β-ionone-dependent TRPV6 channel activation.

FIGURE 4.

β-Ionone-induced current and Ca2+ increase depend on the expression of TRPV6 channels. A, LNCaP cells co-transfected with TrpV6 siRNA 1 and an EGFP-encoding plasmid. P, patch pipette. B, temporal development of mean β-ionone-induced current obtained from voltage ramp recordings at −80 mV in cells co-expressing EGFP and targeting TrpV6 siRNA 1 (black, V6RNAi 1) or EGFP and negative control TrpV6 siRNA 1 (gray, ctrRNAi 19). In cells expressing target TrpV6 siRNA 1 (and EGFP) the current was significantly diminished, whereas cells expressing the negative control TrpV6 siRNA (and EGFP) showed the typical β-ionone-induced current. C, representative I-V relationships measured during β-ionone stimulation in single cells expressing either target TrpV6 siRNA (black) or negative control TrpV6 siRNA (gray). D, mean maximal amplitudes of β-ionone-induced currents measured in untransfected and transfected cells. Ctr, untransfected; ctrV6RNAi 1, negative control TrpV6 siRNA 1; V6RNAi 1, target TrpV6 siRNA 1; scrV6RNAi 2, scrambled TrpV6 siRNA 2; V6RNAi 2, target TrpV6 siRNA 2. Both target TrpV6 siRNA 1 and TrpV6 siRNA 2 expression significantly diminished the β-ionone-induced current (p < 0.001). Negative control TrpV6 siRNA 1 or scrambled TrpV6 siRNA 2 had no effect on the current. The number of analyzed cells is indicated above the bars. E–G, temporal development of the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase measured with fura-2 Ca2+ imaging. Data are displayed averaged with two-sided standard error of mean. Application of β-ionone is indicated. E, response measured in untransfected control cells (n = 20). F, β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in V6RNAi 2 cells (n = 15). G, β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in untransfected cells without extracellular Ca2+ (≤1 nm) (n = 15). H, mean maximal β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in cells expressing TrpV6 siRNA 2 and under Ca2+-free conditions, normalized to the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in untransfected cells, respectively. Under both conditions the response is significantly reduced (TrpV6-siRNA 2, 38 ± 7%, p < 0.001; Ca2+-free, 29 ± 6%, p < 0.001). I, expression analysis of TrpV6 transcripts in RNAi-treated LNCaP cells via quantitative real-time PCR (mean ± S.D.). GAPDH was used to normalize the mRNA levels, a value of 1 refers to the expression level of TrpV6 in nontransfected control cells.

Next, we asked whether TRPV6 channel activation also contributes to the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase observed in imaging experiments (13). In cells transfected with TrpV6 siRNA 2, the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase was significantly reduced compared with untransfected control cells (Fig. 4, E, F, and H). When untransfected cells were stimulated with β-ionone in the absence of external Ca2+ ions, we observed a similar decrease (Fig. 4, G and H), which was not significantly different from the response after TrpV6 down-regulation. All measurements were corrected for a small, stable base-line shift observed in unstimulated cells (supplemental Fig. S4A). Under both conditions we still observe a small Ca2+ increase, suggesting that the TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ increase is supplemented by release from intracellular stores. The response delay of the β-ionone-induced increase in cytosolic Ca2+ was similar to the TRPV6-dependent current measured in whole cell patch clamp. The Ca2+ increase occurred with a delay of 66 ± 9.6 s in the cell protrusion and a just slightly longer delay in the cell body (84 ± 8.9 s, n = 25; supplemental Fig. S4, B and C). Together, these data show that the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in LNCaP cells critically depends on TRPV6 channel expression.

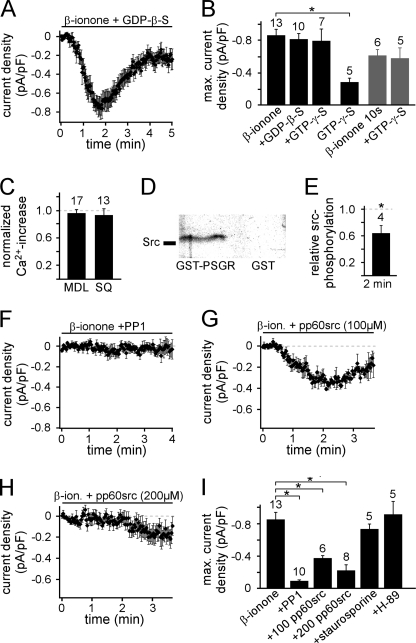

Src Kinase Mediates the β-Ionone-induced Signaling

We next aimed to identify the signaling cascade functionally linking PSGR and TRPV6. Because PSGR is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family, we investigated the involvement of G proteins. We replaced GTP in the pipette solution by its nonhydrolyzable analogs GDPβS (2 mm) or GTPγS (0.5 mm) and thus “locked” G proteins in their inactive or active states, respectively. Neither treatment significantly changed the β-ionone-induced current (Fig. 5, A and B, and supplemental Table S1). β-Ionone was usually applied continuously, possibly masking an effect of GTPγS. Therefore, we additionally shortened the β-ionone stimulation (10 s at the beginning of the experiment). The induced current did not differ in delay, rise time, maximal amplitude, or decay when the pipette solution contained either GTP or GTPγS (Fig. 5B and supplemental Table S1). GTPγS without β-ionone stimulation did not induce a current (Fig. 5B). We further stimulated Gαs-like proteins with cholera toxin. Cholera toxin induced a symmetrical current. At no time were we able to detect a TRPV6-like inwardly rectifying current (supplemental Fig. S6). Taken together, these results suggest that the β-ionone-induced signaling cascade does not depend on G protein activation.

FIGURE 5.

β-Ionone-mediated current induction depends on Src kinase activation. A, time course of the mean β-ionone-induced whole cell current in the presence of 2 mm GDPβs infused via the patch pipette. There was no significant difference in the mean current under control conditions (delay = 47.4 ± 6.0 s, τ = 38.0 ± 5.0 s, Imax = −0.81 ± 0.07 pA/pF, response rate = 71% n = 10/14). B, mean maximal current amplitudes in the presence of GDPβS or GTPγS. The number of cells measured is indicated over the bars. C, mean amplitude of the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in the presence of either 50 μm MDL12330A or 300 μm SQ22536 (10-min preincubation) normalized to β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in untreated cells. D, in vitro binding assay of purified Src kinase and purified C terminus of PSGR (as GST fusion protein). Proteins were isolated by GST pulldown and immunoblotted with Src antibody. GST without PSGR C terminus was used as a negative control (n = 3 independent experiments). E, amount of Src kinase phosphorylation determined with Western blot analysis using a specific antibody that detects only Src kinases phosphorylated at Tyr527. Shown is mean value measured after stimulation with β-ionone for 2 min relative to the value obtained from untreated LNCaP cells (n = 4 independent experiments for each condition). β-Ionone stimulation significantly decreased the amount of inactive, phosphorylated Src kinases (p < 0.05), thus inducing Src kinase activation. F, G, and H, temporal development of the mean β-ionone-induced whole cell current in the presence of 10 μm Src kinase inhibitor PP1 analog (20-min preincubation at 37 °C) (F) as well as 100 μm (G) and 200 μm (H) Src kinase inhibitory peptide pp60 c-src (521–533, phosphorylated) infused via the patch pipette, respectively. I, mean maximal β-ionone-induced current amplitude in the presence of PP1 (10 μm), pp60src (100 and 200 μm), staurosporine (1 μm, 10-min preincubation at 37 °C), and H-89 (10 μm, 1-h preincubation at 37 °C). The number of cells is indicated above the bars.

In the canonical pathway utilized by olfactory sensory neurons the Gαolf-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase ultimately leads to a Ca2+ influx through cAMP-gated ion channels (22). However, the β-ionone-induced Ca2+ increase in LNCaP cells was not inhibited by the adenylyl cyclase inhibitors MDL12330A (50 μm) (23) and SQ22536 (300 μm) (24) (Fig. 5C), which effectively inhibit olfactory receptor signaling in olfactory sensory neurons (25). These findings support our hypothesis that β-ionone activates an alternative signaling pathway.

Some GPCRs are able to activate Src family tyrosine kinases by direct binding without G protein involvement (26–30). Interestingly, it was reported previously that the constitutive activity of recombinant TRPV6 channels was enhanced by Src family kinase-mediated phosphorylation (31, 32). We therefore investigated the possible role of Src in β-ionone-induced signaling. Using an in vitro binding assay we examined whether Src kinases can bind directly to PSGR. We found that the purified C terminus of PSGR (as a GST fusion protein) binds to purified Src kinase (Fig. 5D). We did not observe interaction of Src kinase and GST without PSGR. Thus, PSGR can interact directly with Src kinases without G protein involvement. Next, we investigated whether stimulation of PSGR leads to an activation of Src. Src kinase activity is negatively regulated by phosphorylation of Tyr527 (33). We therefore examined the phosphorylation state of Tyr527 using Western blot analysis. Stimulation of LNCaP cells with β-ionone for 2 min significantly diminished the relative amount of Src kinases phosphorylated at Tyr527 (Fig. 5E). This shows that β-ionone stimulation induces activation of Src kinases, maybe via direct interaction between PSGR and Src. Longer stimulation (5, 10, and 30 min) led to the same results (data not shown). To confirm that Src kinase activation is involved in the β-ionone-induced current activation, we used pharmacological tools to inhibit Src kinases. Preincubation of LNCaP cells with PP1 analog (10 μm), a Src kinase family inhibitor (34, 35), abolished β-ionone-elicited currents (Fig. 5, F and I). Furthermore, we infused the cells with a peptide that specifically binds to the SH2 domain of activated Src kinases and thus inhibits their activity (pp60 c-src (521–533) (phosphorylated), pp60src) (36–38). This peptide inhibited the β-ionone-induced current dose-dependently. While we observed a small but significantly reduced current in the presence of 100 μm pp60src, the current development was completely prevented by 200 μm pp60src (Fig. 5, G–I, and supplemental Table S1). In contrast, inhibition of other protein kinases with staurosporine (1 μm) or H-89 (10 μm) had no significant effect on the β-ionone-induced current (Fig. 5I and supplementary Table S1). Staurosporine inhibits a variety of protein kinases including protein kinase C (39, 40). H-89 targets protein kinase A (PKA) (41, 42) but also inhibits many other protein kinases (43). The lack of inhibition by these two inhibitors strengthens the hypothesis that Src kinases play a central role in the β-ionone-activated signaling pathway.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report that activation of the G protein-coupled receptor PSGR by β-ionone leads to a Src kinase-dependent influx of Ca2+ ions via TRPV6 channels in LNCaP cells. Thus, we present an endogenous activation mechanism for TRPV6 downstream of a GPCR and the first electrophysiological characterization of endogenous TRPV6 channels.

β-Ionone activated a current with a rather slow temporal development as typically seen for responses induced by other metabotropic receptors in LNCaP cells (6, 44). Key features of the β-ionone-induced conductance are strong inward rectification, anomalous mole fraction behavior (revealing a high preference for Ca2+ ions) (8), increased permeability for Na+ in the absence of divalent ions, permeability for Ba2+ and Sr2+ and sensitivity to the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. These features are shared by store-operated channels, TRPV5 and TRPV6 channels (8, 45).

However, our findings make a substantial involvement of store-operated channels highly unlikely. The β-ionone-induced current is potentiated at positive membrane potentials. It is also potentiated by 100 μm 2-APB at negative, but not at positive membrane potentials. Both effects are key features of TRPV6 channels and are not observed for store-operated currents (15, 19, 20). The store-operated channels Orai 1–3 are either inhibited (Orai 1 and 2) or even activated (Orai 3) by this 2-APB concentration (17, 18). 2-APB-activated Orai 3 channels show a current at positive and negative potentials. In LNCaP cells, we did not observe any current activation by 2-APB, suggesting that Orai 3 is not expressed in these cells. When we activated store-operated channels via store depletion by thapsigargin, the current was inhibited by 2-APB after a short potentiation, consistent with previous observations (15, 46, 47). Our finding that pharmacological prevention of store depletion (and thus activation of store-operated channels) did not affect the β-ionone-induced current supports the hypothesis that the channels activated by β-ionone are receptor-, but not store-operated.

Extracellular Ca2+ ions block the β-ionone-induced monovalent current with similar IC50 values as reported for TRPV5 and TRPV6 channels (β-ionone-induced, 100 nm; TRPV5, 200 nm (48); TRPV6, 150 nm (8)), whereas the reported IC50 values for Ca2+ inhibition of Orai channels are much higher (∼20 μm) (49). Furthermore, store-operated currents show a fast decline in DVF solution, whereas TRPV6-mediated currents are stable under these conditions as observed here for the β-ionone-induced current. The Ba2+ permeability of the β-ionone-activated channels (0.32 ± 0.05) is similar to the permeability of homomeric TRPV6 (0.39 ± 0.03) (8), but differs from those reported for store-operated channels in LNCaP cells (0.65) (47) and for heterologously expressed TRPV5 channels (0.69 ± 0.05) (8). The observed single-channel conductance of 49 pS is very similar to the conductance reported for recombinant TRPV6 channels (42–58 pS) (16), but differs from the one reported for recombinant TRPV5 (77–91 pS) (50–52) under the same DVF conditions. Given a single-channel conductance of 49 pS, the β-ionone-induced current in LNCaP cells is conducted by only 12–13 channels. A rather low endogenous TRPV6 expression level was also shown before (19). This low number of activated channels explains why we did not observe a current increase at negative potentials due to time-dependent removal of the intracellular Mg2+ block, a property of recombinant TRPV6 channels (15). Taken together, all properties of the β-ionone-dependent current match currents mediated by TRPV6 channels, but differ either substantially or partially from currents through store-operated or TRPV5 channels.

Interestingly, prolonged incubation with β-ionone inhibits the proliferation rate of LNCaP cells (13) showing that even activation of only some channels can have profound effects. Although endogenous TRPV6 activity seems to enhance proliferation (53), overactivation of TRPV6 signaling by prolonged stimulation inhibits proliferation.

To confirm the molecular identity of the activated channels we performed knockdown experiments with two independent siRNAs. Although thapsigargin-activated currents were not significantly different in cells with reduced TrpV6 expression, the β-ionone-induced current was significantly diminished. Given the low endogenous expression level (12–13 channels activated per cell) quantitative control of protein knockdown is impossible. Rescue of the β-ionone-induced current by co-transfection of a siRNA-resistant TRPV6 construct was also not feasible because TRPV6 channel overexpression leads to constitutive open channels. However, we were able to show that the amount of TrpV6 mRNA is significantly reduced. Taken together with the parallel use of two different experimental RNA interference approaches (siRNA transfection and vector-based in vivo sh/siRNA synthesis) with different targeting sequences our data strongly support the interpretation that the observed current reduction results from decreased TRPV6 levels. The intracellular Ca2+ increase was also significantly reduced, demonstrating that TRPV6-mediated Ca2+ influx either accounts for or triggers most of the β-ionone-induced response measured in imaging experiments.

Having identified both the receptor (PSGR) and the downstream activated ion channel (TRPV6) that mediate β-ionone-induced Ca2+-influx, we investigated the linking signaling cascade. Our data show that β-ionone does not activate a cAMP-PKA signaling cascade. Neither adenylyl cyclase nor PKA inhibition had an effect on the β-ionone-induced signaling. Our observation that Gαs activation by cholera toxin induced a current is in agreement with the literature as several groups described a cAMP-PKA pathway in LNCaP cells (54, 55). However, the cholera toxin-induced current bears no similarities with the β-ionone-induced current.

Focusing on rather unconventional signaling cascades we discovered a key role of Src kinase. β-Ionone stimulation induced the dephosphorylation of Tyr257 in the C terminus of Src. This dephosphorylation leads to Src activation. Additionally, inhibition of Src kinase abolishes the β-ionone-induced current in LNCaP cells, which is in agreement with the previously reported modulation of recombinantly expressed TRPV6 activity (31, 32). We decided not to use pharmacological Src kinase activators because Src kinase-dependent regulation of other channels (e.g. TRPC3 and TRPV1) (56–58) has been shown. The lacking effects of the rather broad protein kinase inhibitors staurosporine and H-89 additionally emphasize the importance of Src in the PSGR-induced current. However, we cannot exclude the involvement of further yet unknown signaling molecules.

Interfering with G protein signaling by replacement of GTP in the intracellular solution by GDPβS or GTPγS (59, 60) had no effect, indicating that signaling via Src and TRPV6 does not depend on G protein activation. Instead, we found that Src binds directly to the C terminus of PSGR. An activation of Src family tyrosine kinases by GPCRs has been reported before (27). Furthermore, activation by direct Src kinase binding, independently of G proteins, has been described for β2-adrenergic receptors (28), 5-HT6 (30), P2Y2 (26), and M3 muscarinic receptors (29).

Although it would be interesting to investigate the PSGR/Src/TRPV6 signaling in a recombinant system, the low expression level of recombinant PSGR as well as its promiscuous signaling (e.g. store depletion in HEK cells) combined with constitutively active recombinant TRPV6 channels make this impossible. To the best of our knowledge, specific activation of native TRPV6 channels downstream of a specific receptor has not been described before (12). TRPV6 channels are involved in the 17β-estradiol-induced Ca2+ increase in human colonic cells (61), but the signaling molecules (including the receptor) linking 17β-estradiol to TRPV6 activation are unknown. To date, all electrophysiological studies on TRPV6 investigated heterologously overexpressed channels which are constitutively active under these conditions (8, 9, 21). We also observed spontaneous TRPV6-like currents when we overexpressed TRPV6 channels in LNCaP cells. However, our data suggest that TRPV6 channels endogenously expressed in LNCaP cells are not constitutively active, but can be activated downstream of PSGR/Src kinase signaling.

Based on the data presented here, we suggest that Src kinase is the messenger linking PSGR to TRPV6 in LNCaP prostate cells and that Src kinase binds directly to PSGR. Thus, we identified PSGR, Src kinase, and TRPV6 as major constituents of a novel Ca2+ signaling pathway that is potentially involved in prostate cell proliferation and carcinogenesis. In contrast to other studies, which characterized TRPV6 overexpressed in various cell lines, we show here an activation of endogenously expressed TRPV6 channels downstream of PSGR and present the first analysis of its physiological behavior in situ.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Zhang for assistance in early stages of this project and J. Panten (Symrise, Holzminden, Germany) for providing β-ionone. We also thank H. Bartel, J. Gerkrath (Ruhr-University Bochum) and C. Engelhardt (RWTH Aachen) for excellent technical assistance. Marc Spehr is a Lichtenberg-Professor of the Volkswagen Foundation.

This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB642, EXC257, and SP724/2-1).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Methods, Table S1, and Figs. S1–S6.

- TRPV5 and TRPV6

- transient receptor potential vanilloid type 5 and type 6 channel

- 2-APB

- 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate

- DVF

- divalent free

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- ERS

- extracellular recording solution

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- GDPβS

- guanosine 5′-2-O-(thio)diphosphate

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- LNCaP

- lymph node carcinoma of the prostate

- NMDG+

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- pF

- picofarad

- PSGR

- prostate-specific G protein-coupled receptor

- PP1

- 4-amino-1-tert-butyl-3-(1′-naphthyl)-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- pS

- picosiemens.

REFERENCES

- 1. Clapham D. E. (2007) Cell 131, 1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang L., Barritt G. J. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 8365–8373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanchez M. G., Sanchez A. M., Collado B., Malagarie-Cazenave S., Olea N., Carmena M. J., Prieto J. C., Diaz-Laviada I. (2005) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 515, 20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sydorenko V., Shuba Y., Thebault S., Roudbaraki M., Lepage G., Prevarskaya N., Skryma R. (2003) J. Physiol. 548, 823–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanden Abeele F., Lemonnier L., Thébault S., Lepage G., Parys J. B., Shuba Y., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 30326–30337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thebault S., Flourakis M., Vanoverberghe K., Vandermoere F., Roudbaraki M., Lehen'kyi V., Slomianny C., Beck B., Mariot P., Bonnal J. L., Mauroy B., Shuba Y., Capiod T., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 2038–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peng J. B., Chen X. Z., Berger U. V., Weremowicz S., Morton C. C., Vassilev P. M., Brown E. M., Hediger M. A. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoenderop J. G., Vennekens R., Müller D., Prenen J., Droogmans G., Bindels R. J., Nilius B. (2001) J. Physiol. 537, 747–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wissenbach U., Niemeyer B. A., Fixemer T., Schneidewind A., Trost C., Cavalie A., Reus K., Meese E., Bonkhoff H., Flockerzi V. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19461–19468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fixemer T., Wissenbach U., Flockerzi V., Bonkhoff H. (2003) Oncogene 22, 7858–7861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoenderop J. G., Nilius B., Bindels R. J. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85, 373–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vriens J., Appendino G., Nilius B. (2009) Mol. Pharmacol. 75, 1262–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neuhaus E. M., Zhang W., Gelis L., Deng Y., Noldus J., Hatt H. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 16218–16225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xu L. L., Stackhouse B. G., Florence K., Zhang W., Shanmugam N., Sesterhenn I. A., Zou Z., Srikantan V., Augustus M., Roschke V., Carter K., McLeod D. G., Moul J. W., Soppett D., Srivastava S. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 6568–6572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voets T., Prenen J., Fleig A., Vennekens R., Watanabe H., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J., Droogmans G., Penner R., Nilius B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47767–47770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yue L., Peng J. B., Hediger M. A., Clapham D. E. (2001) Nature 410, 705–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lis A., Peinelt C., Beck A., Parvez S., Monteilh-Zoller M., Fleig A., Penner R. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 794–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19265–19273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bödding M., Fecher-Trost C., Flockerzi V. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50872–50879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bödding M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7022–7029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schindl R., Kahr H., Graz I., Groschner K., Romanin C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26950–26958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spehr M., Munger S. D. (2009) J. Neurochem. 109, 1570–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guellaen G., Mahu J. L., Mavier P., Berthelot P., Hanoune J. (1977) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 484, 465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harris D. N., Asaad M. M., Phillips M. B., Goldenberg H. J., Antonaccio M. J. (1979) J. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 5, 125–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen S., Lane A. P., Bock R., Leinders-Zufall T., Zufall F. (2000) J. Neurophysiol. 84, 575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu J., Liao Z., Camden J., Griffin K. D., Garrad R. C., Santiago-Pérez L. I., González F. A., Seye C. I., Weisman G. A., Erb L. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8212–8218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luttrell D. K., Luttrell L. M. (2004) Oncogene 23, 7969–7978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun Y., Huang J., Xiang Y., Bastepe M., Jüppner H., Kobilka B. K., Zhang J. J., Huang X. Y. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Swayne L. A., Mezghrani A., Varrault A., Chemin J., Bertrand G., Dalle S., Bourinet E., Lory P., Miller R. J., Nargeot J., Monteil A. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 873–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yun H. M., Kim S., Kim H. J., Kostenis E., Kim J. I., Seong J. Y., Baik J. H., Rhim H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5496–5505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sternfeld L., Krause E., Schmid A., Anderie I., Latas A., Al-Shaldi H., Köhl A., Evers K., Hofer H. W., Schulz I. (2005) Cell. Signal. 17, 951–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sternfeld L., Anderie I., Schmid A., Al-Shaldi H., Krause E., Magg T., Schreiner D., Hofer H. W., Schulz I. (2007) Cell Calcium 42, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schlessinger J., Lemmon M. A. (2003) Sci. STKE 2003, RE12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mariappan M. M., Senthil D., Natarajan K. S., Choudhury G. G., Kasinath B. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28402–28411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bishop A. C., Ubersax J. A., Petsch D. T., Matheos D. P., Gray N. S., Blethrow J., Shimizu E., Tsien J. Z., Schultz P. G., Rose M. D., Wood J. L., Morgan D. O., Shokat K. M. (2000) Nature 407, 395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roussel R. R., Brodeur S. R., Shalloway D., Laudano A. P. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 10696–10700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Songyang Z., Shoelson S. E., Chaudhuri M., Gish G., Pawson T., Haser W. G., King F., Roberts T., Ratnofsky S., Lechleider R. J. (1993) Cell 72, 767–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raingo J., Castiglioni A. J., Lipscombe D. (2007) Nat. Neurosci. 10, 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burgess G. M., Mullaney I., McNeill M., Dunn P. M., Rang H. P. (1989) J. Neurosci. 9, 3314–3325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garcia D. E., Brown S., Hille B., Mackie K. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 2834–2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wozny C., Maier N., Fidzinski P., Breustedt J., Behr J., Schmitz D. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 14358–14362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Avila G., Aguilar C. I., Ramos-Mondragón R. (2007) J. Physiol. 584, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lochner A., Moolman J. A. (2006) Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 24, 261–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thebault S., Roudbaraki M., Sydorenko V., Shuba Y., Lemonnier L., Slomianny C., Dewailly E., Bonnal J. L., Mauroy B., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1691–1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoth M., Penner R. (1992) Nature 355, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prakriya M., Lewis R. S. (2001) J. Physiol. 536, 3–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vanden Abeele F., Roudbaraki M., Shuba Y., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15381–15389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vennekens R., Prenen J., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J., Droogmans G., Nilius B. (2001) J. Physiol. 530, 183–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Putney J. W., Jr. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17548–17556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nilius B., Vennekens R., Prenen J., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J., Droogmans G. (2000) J. Physiol. 527, 239–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yeh B. I., Sun T. J., Lee J. Z., Chen H. H., Huang C. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51044–51052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. de Groot T., Lee K., Langeslag M., Xi Q., Jalink K., Bindels R. J., Hoenderop J. G. (2009) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 1693–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lehen'kyi V., Flourakis M., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2007) Oncogene 26, 7380–7385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cox M. E., Deeble P. D., Bissonette E. A., Parsons S. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13812–13818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shah G. V., Rayford W., Noble M. J., Austenfeld M., Weigel J., Vamos S., Mebust W. K. (1994) Endocrinology 134, 596–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vazquez G., Wedel B. J., Kawasaki B. T., Bird G. S., Putney J. W., Jr. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40521–40528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kawasaki B. T., Liao Y., Birnbaumer L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 335–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jin X., Morsy N., Winston J., Pasricha P. J., Garrett K., Akbarali H. I. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 287, C558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ma J. Y., Li M., Catterall W. A., Scheuer T. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 12351–12355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mederos y Schnitzler M., Storch U., Meibers S., Nurwakagari P., Breit A., Essin K., Gollasch M., Gudermann T. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 3092–3103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Irnaten M., Blanchard-Gutton N., Harvey B. J. (2008) Cell Calcium 44, 441–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]