Abstract

We have determined the solution structure of Mth11 (Mth Rpp29), an essential subunit of the RNase P enzyme from the archaebacterium Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus (Mth). RNase P is a ubiquitous ribonucleoprotein enzyme primarily responsible for cleaving the 5′ leader sequence during maturation of tRNAs in all three domains of life. In eubacteria, this enzyme is made up of two subunits: a large RNA (≈120 kDa) responsible for mediating catalysis, and a small protein cofactor (≈15 kDa) that modulates substrate recognition and is required for efficient in vivo catalysis. In contrast, multiple proteins are associated with eukaryotic and archaeal RNase P, and these proteins exhibit no recognizable homology to the conserved bacterial protein subunit. In reconstitution experiments with recombinantly expressed and purified protein subunits, we found that Mth Rpp29, a homolog of the Rpp29 protein subunit from eukaryotic RNase P, is an essential protein component of the archaeal holoenzyme. Consistent with its role in mediating protein–RNA interactions, we report that Mth Rpp29 is a member of the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding fold family. In addition to a structured β-barrel core, it possesses unstructured N- and C-terminal extensions bearing several highly conserved amino acid residues. To identify possible RNA contacts in the protein–RNA complex, we examined the interaction of the 11-kDa protein with the full 100-kDa Mth RNA subunit by using NMR chemical shift perturbation. Our findings represent a critical step toward a structural model of the RNase P holoenzyme from archaebacteria and higher organisms.

Ribonuclease (RNase) P is an essential and ubiquitous enzyme primarily responsible for cleaving the 5′ leader sequence during maturation of tRNAs in all three domains of life (1, 2). In bacteria, this ribonucleoprotein enzyme is made up of a large RNA subunit (≈120 kDa) responsible for mediating catalysis (3) and a small protein cofactor (≈15 kDa) that modulates substrate recognition (4–6) and is required for efficient in vivo catalysis (7). In higher organisms, RNase P is made up of one RNA and several protein subunits (8–12).

Despite significant similarity between the RNA subunits of bacterial and archaeal RNase P (13), database mining of the available archaeal genomes has failed to identify a protein homologous to the bacterial RNase P protein. Instead, analysis of purified RNase P from Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus (Mth) identified four proteins (Mth11, Mth1618, Mth687, and Mth688) that are homologous to those of eukaryotic nuclear RNase P (14): Rpp29, Rpp21, Pop5, and Rpp30, respectively. These four proteins were subsequently shown to be those required for in vitro reconstitution of archaeal RNase P. Using bacterially expressed, purified proteins and in vitro-transcribed P RNA from the hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus horikoshii, precursor tRNA (ptRNA)-processing activity could be recovered by the addition of these four proteins, whereas no activity was observed upon addition of any single protein subunit (15).

We report here the solution structure of Mth11/Mth Rpp29, the homolog of the human RNase P protein Rpp29 (16, 17), encoded by Mth ORF 0011 (14, 18, 19). Mth Rpp29 is a small 93-residue protein containing a domain (Pfam UPF0086) that is highly conserved both within and between Archaea and Eukarya (Fig. 1). The eukaryotic homologs of the protein contain, in addition to the conserved domain, a domain at the N terminus that includes a nucleolar targeting signal and may have other functions that are dispensable in an organism lacking a nucleus. The essentiality of Mth Rpp29 to RNase P activity was confirmed in an in vitro reconstitution assay.

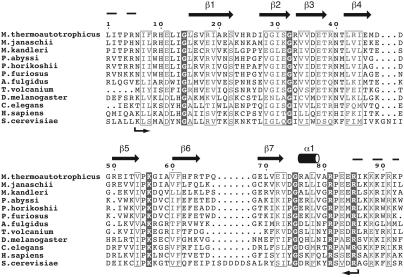

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of Mth Rpp29 with Rpp29 sequences from Archaea and Eukarya. Alignment was generated with clustalw (57) and colored according to similarity by using a Risler scoring matrix (58); shaded residues indicate identity, and boxed residues indicate a global similarity score >0.7. Secondary structural features observed in the structure ensemble are indicated. Arrows indicate the core of the protein protected from trypsin digestion as identified by electrospray-MS (9,114 Da expected; 9,115 Da observed).

To provide insights into the role of Mth Rpp29 in RNase P assembly, we examined the interaction of the protein with the full 314-nt Mth RNA subunit by using NMR chemical shift perturbation. The data have allowed us to identify residues in the protein that interact with the nucleic acid. These data are a critical step toward developing a structural model of the complex RNase P holoenzyme from Archaea and higher organisms.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells were cotransformed with Mth11/pET-15b and pARG-U (20, 21) plasmids and grown at 37°C in minimal M9 media (22) containing 1 g/liter 15N ammonium chloride and 2 g/liter 13C glucose as the nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively, supplemented with 30 μg/liter kanamycin, 50 μg/liter carbenicillin, and Eagle Basal Vitamin Mix (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). The cells were induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside when the cells reached OD600 ≈0.6 (mid-log phase), harvested after 4 h by centrifugation (10 min, 5,000 × g, 4°C), and stored at –20°C. Thawed cells were suspended in 30 ml of buffer A (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0/0.5 M KCl) and lysed on ice by sonication, and cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation (30 min at 20,000 × g, 4°C). Mth Rpp29 was purified as reported (23) with the following modifications: the (His)6-affinity tag was removed by incubation at 37°C with thrombin (10 units/mg of Mth Rpp29) for at least 12 h, resulting in a 97-residue protein consisting of four plasmid-encoded residues (Gly-Ser-His-Met) followed by the 93 natively encoded residues. After cleavage of the affinity tag, the protein was purified by C4 reversed-phase HPLC chromatography (Vydac 214TP1010, 1 × 25 cm; 180-ml linear gradient of 35–50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). Pooled fractions were lyophilized and refolded by dissolving in NMR buffer (50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7/50 mM KCl/0.02% sodium azide/10% D2O) to a concentration of ≈4 mg/ml and then concentrated by ultra filtration (Centriprep-3, Amicon). The Mth Rpp30 (Mth688), Mth Rpp21 (Mth1618), and Pfu Pop5 (Pf1378) proteins were obtained in a similar manner (details to be presented elsewhere). Sample purity was assayed by SDS/PAGE with Coomassie blue staining and by electrospray-MS. Protein concentration was estimated by Bradford assay (Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent, Pierce).

Limited Proteolysis. Purified, refolded Mth Rpp29 was subjected to limited proteolysis by adding 5% trypsin (wt/wt) to a protein solution (≈100 μM in NMR buffer) and incubating at room temperature for intervals up to 30 min, quenched with 0.6 mM PMSF, followed by electrospray mass analysis (Q-TOF-II, Micromass, Manchester, U.K.).

Transcription of Mth P RNA. The gene encoding Mth P RNA [Fig. 2a, 309 nt: 1,173,861 to 1,174,169 of gi|15678031 (16, 24)] was obtained by PCR with the Mth genomic DNA as the template and the appropriate gene-specific primers (forward: CGGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATA*ggACCGGGCAAG CCGA AGGGC; reverse: GGaattcACCGGGCATGCCGAGAGTAAC; BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites are italicized, the T7 promoter is underlined, the asterisk denotes the transcription start site, and nucleotides in lowercase are introduced by primers). The PCR product containing the gene, placed under control of a bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase promoter, was then subcloned into pUC19. DNA sequencing confirmed the correct sequence of the full-length P RNA gene. Mth P RNA was generated by in vitro runoff transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (purified in-house) after linearization of the plasmid with EcoRI. In vitro-transcribed RNA (316 nt) was refolded in binding buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/10 mM MgOAc/400 mM NH4OAc/5% glycerol/0.01% Nonidet P-40), while verifying the proper fold by monitoring the ability of the RNA to cleave ptRNATyr under high salt conditions (25).

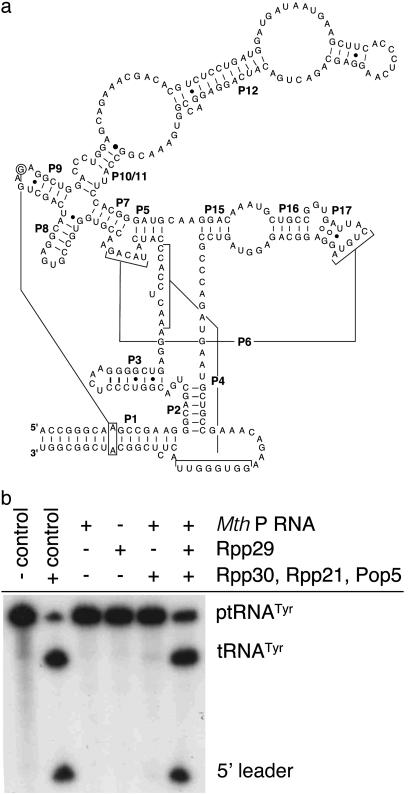

Fig. 2.

In vitro reconstitution of Mth RNase P activity. (a) Sequence and phylogenetically predicted secondary structure of the Mth RNase P RNA subunit (24). (b) Reconstitution experiment shows Mth Rpp29 is essential for effective Mth RNase P activity against E. coli ptRNATyr. The negative control is the substrate alone; positive control is the substrate incubated with E. coli RNase P; Pfu Pop5 was used in place of Mth Pop5.

In Vitro Reconstitution. Reconstitution experiments were performed by incubating Mth P RNA (0.1 μM) with the protein subunits (3 μM) in 10 μl of buffer [50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.6/10 mM MgCl2/800 mM NH4Cl/0.025 units/μl RNasin (Invitrogen), 37°C, 5 min]. Activity was assayed by adding 0.02 pmol of E. coli ptRNAtyr internally labeled with [α-32P]GTP (2 nM) and incubating for 3.5 h. The reactions were quenched with urea, electrophoresed on an 8% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide/7 M urea gel, and analyzed by autoradiography. The Pop5 homolog from Pyroccocus furiosus (Pf1378; see Fig. 1b) was used in place of Mth Pop5 because of presumed problems with solubility and folding in the Mth homolog. All proteins were purified to homogeneity (>95%) and verified to lack independent ptRNA processing activity.

NMR Spectroscopy. NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C on 600- and 800-MHz Bruker (Billerica, MA) Avance DMX and DRX spectrometers equipped with triple-resonance probes and triple-axis pulsed-field gradients. NMR data processing and analysis were performed with nmrpipe (26) and nmrview (27). NMR samples typically contained 1 mM Mth Rpp29 and 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7), 50 mM KCl, and 90% H2O/10% D2O or 100% D2O. Backbone assignments were made by using standard triple resonance spectra [HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, and HNCO] (28, 29) recorded at 600 MHz. Side-chain 1H and 13C resonance assignments were obtained from several 3D spectra: 15N-separated total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) (800 MHz, 40 ms τm, 9.2 kHz nominal B1 field), CCONHTOCSY (600 MHz, τm 13 ms, 8.3 kHz nominal B1 field), 3D HCCH-COSY (600 MHz), and HCCH-TOCSY (600 MHz, τm 12 ms, 8.3 kHz nominal B1 field). Interproton distance restraints were obtained from assignment of nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) cross peaks in 3D 15N-separated NOESY (800 MHz, τm 100 ms) and 13C-separated NOESY spectra (τm 150 ms). Two 13C-separated NOESY spectra were recorded, one in 90% H2O/10% D2O (800 MHz) and one in 100% D2O (600 MHz).

Heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOE data (30) were obtained by recording spectra in an interleaved manner with (NOE) and without (no NOE) 1H saturation achieved via a train of 120° pulses (14 kHz bandwidth) applied every 18 msec for 5 sec. Heteronuclear NOE values were determined from the ratios of the peak intensities between the two spectra.

Mth Rpp29 Structure Determination. The structure of the Mth Rpp29 protein was determined by using the simulated annealing and energy minimization protocols within the cns program suite (31), which identified a full range of structures that are consistent with the distance and angle restraints derived from the NMR data. Distance constraints were derived from the intensities of cross peaks from multidimensional NOE spectra (τm 100–150 ms). Peak intensities were placed into one of three categories: strong (<2.8 Å), medium (2.8–3.4 Å), and weak (3.4–5 Å). Backbone torsion angle restraints for phi and psi torsion angles were obtained from analysis of the backbone chemical shifts with talos (32). Hydrogen bond restraints were obtained from analysis of NOEs and the temperature dependence of amide proton chemical shifts. A final set of 20 refined structures that met the input restraints were selected for analysis; statistics (Table 1) were calculated with procheck-nmr (33).

Table 1. Structure refinement statistics.

| NMR constraints | 1,247 |

| Distance | 1,059 |

| Intraresidue | 488 |

| Sequential (i, i + 1) | 207 |

| Medium range (i, j ≤ 4) | 41 |

| Long range (i, j > 5) | 209 |

| Ambiguous | 114 |

| (Restraints per residue: 11) | |

| Torsion (ϕ, ψ) | 162 |

| H bond | 26 |

| Violations (20 SA structures; no NOE violations > 0.5 Å) | |

| NOE violations (> 0.2 Å) | |

| Number | 1.91 ± 0.684 |

| RMSD, Å | 0.0187 ± 0.0009 |

| Torsion violations | |

| Number > 5 deg | 0.55 ± 0.80 |

| RMSD, deg | 0.66 ± 0.15 |

| Deviation from ideal geometry | |

| Bond length, Å | 0.0025 ± 0.00028 |

| Bond angle, deg | 0.4121 ± 0.0350 |

| RMSD from mean structure (Å) (residues 12-80) | |

| Backbone | 0.55 |

| Heavy atoms | 1.26 |

| Ramachandran analysis, % | |

| Most favored region | 87.3 |

| Additionally allowed region | 12.7 |

RMSD, rms deviation.

NMR of the Mth Rpp29/P RNA Complex. Interactions between Mth Rpp29 and Mth P RNA were examined by using 15N-edited heteronuclear single quantum correlation (HSQC) spectra (800 MHz) at a 1:1 ratio of protein to RNA. The complex was assembled by adding highly concentrated RNA (100 μl; 600 μM) to a protein solution (200 μl; 300 μM), mixed by pipetting, and transferred to a reduced volume NMR tube (Shigemi, Allison Park, PA); final protein and RNA concentrations were 200 μM. Initial spectra recorded under these conditions (low salt, 25°C) were excessively broadened by nonspecific interactions; improved spectra were obtained by addition of 1 M KCl to a final concentration of 400 mM, and increasing the temperature to 50°C. For reference, a spectrum of free protein was recorded in the same buffer and temperature. Backbone amide assignments at 50°C were obtained by recording 15N HSQC spectra at 5° intervals. Weighted average shift perturbations were calculated as (((δΔH)2 + (δΔN/5)2)/2)0.5 (34).

Results

Mth Rpp29 Is an Essential Subunit of Mth RNase P. To test whether Mth Rpp29 is essential to RNase P activity, Mth P RNA was incubated with ptRNA substrate in the absence and presence of the four known protein subunits (14). Using conditions similar to those reported for P. horikoshii RNase P reconstitution (15), no single archaeal protein was able to reconstitute measurable activity (data not shown). However, enzyme activity could be obtained by preincubating the RNA with the four proteins (Fig. 2b). The essentiality of Rpp29 is demonstrated by the lack of activity when Rpp29 was omitted from the reaction (Fig. 2b, compare lanes 5 and 6).

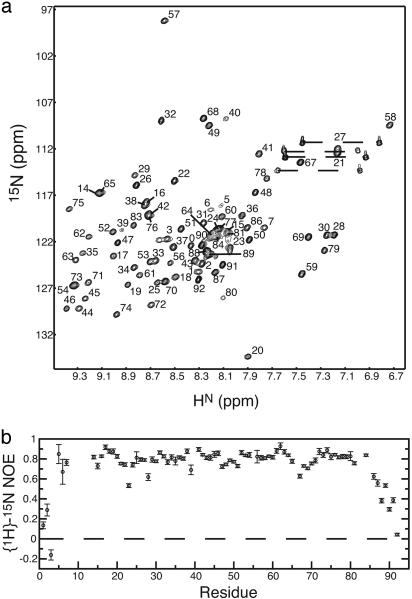

NMR Spectroscopy and Assignments. After removal of the (His)6-tag with thrombin, expressed Mth Rpp29 consisted of the WT protein (93 residues), plus four additional N-terminal residues: GSHM. 2D 1H-15N correlated NMR spectra (Fig. 3a) indicated that the majority of the resonances were well dispersed, typical for a folded protein; however, near random coil chemical shifts and narrow line widths of several resonances indicated that regions of the protein were flexible or disordered. Limited trypsin proteolysis and heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOE data (Fig. 3b) demonstrated that both the N and C termini were flexible or disordered, with the structured protein consisting of the 80 central residues (residues 6–85, see arrows in Fig. 1). Backbone amide resonance assignments (Fig. 3a) could be obtained for all but residues 9–13 and 85, in addition to the five prolines (residues 4, 55, 66, 82, and 93).

Fig. 3.

NMR spectra of Mth Rpp29. (a) 15N HSQC spectrum with backbone amide assignments indicated. (b) Heteronuclear {1H}-15N NOE data of Mth Rpp29 indicates the N- and C-terminal residues are highly flexible. The trypsin-resistant core consists of residues 6–85.

Structure Determination. The solution structure of Mth Rpp29 was well defined for residues 12–80, with a mean backbone rms deviation of 0.6 Å (Fig. 4a). Although proteolysis and heteronuclear NOE data indicate that residues 6–85 are structured, insufficient restraints were obtained for residues 6–11 and 82–85 to properly define their structure. The core of the protein adopts the oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold (OB-fold) (35, 36) and consists of a closed barrel of seven antiparallel β strands and a short 310 helix, α1, near the C terminus. Strands β1, β2, β6, and β7 form a four-stranded β-sheet, whereas strands β3, β4 and β5 form a three-stranded β-sheet. The core of the protein is well packed with highly conserved hydrophobic residues, particularly those at positions 12, 13, 15, 17, 19, 30, 34, 42, 44, 54, 61, 63, 71, 73, and 78. The core appears to be somewhat exposed to solvent, particularly the side flanked by β3 and β7, although it is possible that it could be partially buried by some of the N-terminal 14 residues. The surface of the protein is highly populated by less conserved acidic (Glu, Asp) and basic residues (Arg, His).

Fig. 4.

Mth Rpp29 solution structure. (a) Ensemble of 20 low-energy structures of Mth Rpp29 superposed on the backbone heavy atoms of residues 12–82; for clarity, only the main-chain atoms (N, Cα, and C′) of the structured core residues are shown. Strands are blue, turns and coil regions are gray, and the C-terminal helix is red. (b) Close-up showing a potential salt bridge between the conserved Lys-56 and Glu-37 residues; hydrophobic residues in the core are green. (c) Surface representation illustrates several potential surface salt bridges. The side chains of Lys and Arg residues are blue, Asp and Glu are red, and hydrophobic residues are green. Images were rendered with molmol (59).

Amino acid residues highly conserved across the Rpp29 family (Fig. 1) occupy prominent places in the structure. The first and last invariant glycine residues (Gly-14, Gly-75) form turns flanking secondary structural elements, whereas the invariant Gly-32 allows a sharp turn between strands β2 and β3 on opposing sheets. In the ensemble, the side chain of the invariant Lys-56 is positioned at one edge of the hydrophobic core, where it appears to form a salt bridge with the side chain of Glu-37 (Fig. 4b); the latter is either a Glu or an Asp in all Rpp29 family members (Fig. 1). The other two invariant residues, Arg-81 and Arg-85, are located after the C-terminal helix and preceding the disordered C terminus. The surface of the structured domain (Fig. 4c) exhibits several pairings of basic and acidic residues, indicating possible salt bridges, as well as significant hydrophobic surface area.

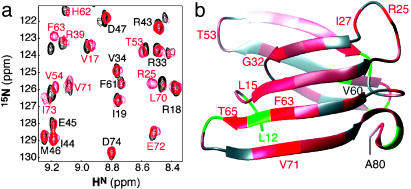

Interactions with the RNA Subunit. At low salt, Rpp29 resonance lines were excessively broadened in the presence of the RNA subunit, presumably because of nonspecific interactions. After addition of salt (400 mM KCl in 50 mM phosphate) and raising the temperature to 50°C, NMR spectra of the complex could be recorded. Comparison of the 15N HSQC spectra of Mth Rpp29 in the absence and presence of the catalytic P RNA subunit (Fig. 5a) reveals many small shift perturbations and localized line broadening, consistent with weak binding. RNA-induced shift perturbations are apparent at multiple sites in the protein; the largest measurable shift perturbations were induced in the amides of Arg-25 in the β1-β2 loop and Phe-63 and Thr-65 in β6 (Fig. 5b). In addition, significant shift perturbations were observed for residues in the flexible N- and C-terminal segments of the domain (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Identification of protein–RNA contacts by 1H-15N correlated NMR of the 113-kDa Mth Rpp29 –RNA complex. (a) Overlay of a portion of the HSQC spectra of free Mth Rpp29 (black) and the 1:1 complex between the 11-kDa (93 residues) protein and 102-kDa (314 nt) Mth P RNA (800 MHz, 50°C, 50 mM phosphate, 400 mM KCl). (b) Weighted average amide proton and nitrogen weighted-average shift perturbations (34) are mapped onto the ribbon diagram of the Rpp29 OB-fold by using a linear color ramp from gray (no change) to red [Δav(NH) = 0.15]. Residues in green are those for which the effect of RNA binding could not be assessed.

Discussion

Despite significant differences in the primary sequences of the RNA and protein subunits of bacterial RNase P, their overall structures are remarkably conserved (1, 2, 37–39), likely a reflection of the evolutionary pressure provided by the conserved function of the enzyme. On the other hand, although the RNA subunits of archaebacterial RNase P are similar in secondary structure to their bacterial counterparts (14, 25), sequence analysis suggests that the archaeal protein subunits are structurally unrelated to the bacterial protein, exhibiting instead sequence homology to proteins from the eukaryotic enzyme (14). Until recently (15), the inability to reconstitute the eukaryotic and archaeal enzymes from their purified components made it difficult to demonstrate a direct functional role for any of the protein subunits originally identified by virtue of their association with biochemically purified enzyme activity (8, 14, 40–44), leaving open the possibility that an as yet undiscovered bacterial-like protein was required for activity. Furthermore, the poor sequence homology of the four identified subunits of archaeal RNase P to proteins of known structure furnished few clues as to their roles in RNase P-mediated ptRNA processing. This impasse has now been overcome by the demonstration that a functional archaeal RNase P holoenzyme can be reconstituted from the in vitro-transcribed P RNA and recombinantly expressed and purified Rpp29, Rpp21, Rpp30, and Pop5 proteins of P. horikoshii, a hyperthermophile (15), and Mth, a moderate thermophile (Fig. 2b). Moreover, although the functional roles of the individual protein subunits remain to be elucidated, both studies demonstrate that Rpp29 is essential for enzyme activity in a reconstitution assay. This study on Mth Rpp29 now provides a glimpse into structure–function relationships in archaeal/eukaryotic RNase P.

This investigation has revealed that Rpp29 is a member of the OB-fold family of proteins (35, 36). Although OB-fold containing proteins have been difficult to identify from primary sequence, they are well represented in ribonucleoprotein complexes from all three domains of life. Examples include the S1 and S17 bacterial ribosomal proteins (45), the anticodonrecognition domain of aspartyl and lysyl tRNA synthetases, single-stranded DNA binding proteins from Thermus thermophilus and Thermus aquaticus (46), translation initiation factor aIF-1A from Methanococcus jannaschii (47), the single-stranded telomeric DNA binding protein from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cdc13 (48), and the N-terminal segment of human translation initiation factor α (49). Not surprisingly, Mth Rpp29 exhibits no significant structural similarity to the protein subunit of bacterial RNase P, which adopts an α-β sandwich fold (37–39).

The surface of the structured core of Rpp29 (Fig. 4c) exhibits a unique array of cationic, anionic, and hydrophobic patches that could mediate specific protein–protein and protein–RNA recognition. In addition to the structured core containing the OB-fold, the unstructured N- and C-terminal extensions bear several highly conserved arginine and lysine residues (Fig. 1) that could provide additional stabilizing interactions with RNA. Indeed, it seems likely that the hydrophobic patches and salt bridges of the surface of the protein, as well as the unstructured N and C termini may have critical roles in induced-fit recognition of the RNA and other subunits (50, 51). Such an expectation is not without precedent: highly charged and unstructured N or C termini in the globular ribosomal proteins, L15, L21e, and L37e (52) penetrate the ribosome and make important structural contacts with the ribosomal RNA (52, 53).

What is the nature of the interaction of Mth Rpp29 with the RNA subunit? NMR spectra of the RNP complex (Fig. 5a) indicate that in 400 mM salt, the interaction of Mth Rpp29 with the RNA subunit is relatively weak and exhibits spectra characteristic of rapid exchange between the free and bound states. In addition, footprinting studies examining the susceptibility of Mth P RNA to digestion by RNase T1 or RNase V1 in the absence and presence of Rpp29 indicate that the two components do not interact strongly in the absence of the other proteins (H.-Y.T. and V.G., unpublished results). Nevertheless, comparison of the 15N-edited HSQC spectra of Mth Rpp29 free and in complex with the P RNA yields specific information about residues that interact with the P RNA. Given that the P RNA is much larger than Mth Rpp29 (by 10-fold) and that chemical shift perturbations were observed on both ends of the protein, it is likely that the P RNA wraps around Mth Rpp29 or that the protein fits into a large pocket on the RNA. The increased salt concentration (400 mM) used to obtain spectra of Mth Rpp29 in complex with the P RNA should reduce the possibility that the observed spectral perturbations are dominated by nonspecific interactions between a cationic protein and an anionic RNA. In fact, many of the residues exhibiting the largest shift changes were not cationic arginines or lysines (Fig. 5), but include hydrophobic (e.g., Val-17, Ile-27, Phe-63, Ile-73) and polar (e.g., Thr-53, Thr-65) residues. Indeed, a recent report demonstrating a significant role for hydrophobic residues in nucleic acid binding by the telomere-end binding protein, Cdc13, a member of the OB-fold protein family (36), indicates such observations are not unique to this system.

We speculate that one role of Rpp29 is to stabilize the active conformation of the RNA subunit by forming favorable hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. However, although a single protein is enough to complete the bacterial enzyme, no single archaeal RNase P protein can sufficiently stabilize the RNA structure to promote activity (Fig. 2 and ref. 15). Instead, it appears that the protein subunits exhibit cooperativity in their ability to promote catalysis (H.-Y.T. and V.G., unpublished work). Nevertheless, with the caveat that all of the native RNA–protein interactions between these subunits might be achieved only when all of the protein components of the holoenzyme are present, the NMR chemical shift perturbation data presented here provide insights into possible protein–nucleic acid contacts in the holoenzyme. Furthermore, based on the data, we suggest that the protein interacts with the RNA via the conserved OB-fold domain and that the highly conserved C terminus (and potentially the N terminus) of Mth Rpp29 becomes structured upon binding to the Mth P RNA (and/or other protein subunits).

The proposal that Rpp29 functions via direct interaction with the RNA subunit is also supported by the results from earlier studies. For instance, three hybrid assays in yeast revealed that both human and yeast Rpp29 interact with their respective RNase P RNA subunit (54–56). Additionally, findings from a genetic study with RNase MRP, an endonuclease related to RNase P, further support the idea that Rpp29 is involved in binding its cognate RNA subunit (41). In all eukaryotes, RNase MRP is one of a series of enzymes involved in rRNA processing. RNase MRP and RNase P, although acting on different substrates, are related in that they are both ribonucleoprotein complexes that share all but one protein subunit and have similar RNA subunits. In a study of S. cerevisiae RNase MRP (41), one class of extragenic suppressors of a temperature-sensitive mutation rrp2–2 in the RNA subunit of RNase MRP were mapped to alterations of a single codon in the POP4/RPP29 gene. Based on this observation, it was proposed that the rpp2–2 mutation in the MRP RNA might disrupt RNA–protein interactions with Pop4 (Rpp29), a reasonable premise that has so far been untested.

The mechanistic and structural details of how Mth Rpp29 interacts with the catalytic P RNA and other protein subunits remain to be uncovered. Those studies should help reveal the function of Mth Rpp29 within the holoenzyme and allow comparisons between the functions of the protein subunits of bacterial and archaeal/eukaryotic RNase P. Given the stark difference between the structure of Rpp29 and the bacterial protein subunit, it is unclear why the many subunits of archaeal RNase P are required to supplant the function of their single bacterial counterpart. Although a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of archaeal RNase P will necessitate detailed studies of all subunits and their complexes, structural characterization of Mth Rpp29 and its interaction with the catalytic P RNA represent important steps toward elucidating structure–function correlates in the holoenzyme.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Amero, C. Cottrell, S. Kraynik, W. Woznick, and C. Yuan (Ohio State University) for assistance and technical support; J. W. Brown (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) for helpful discussions and the Rpp21 expression plasmid; A. Edwards and S. Arrowsmith (University of Toronto, Toronto) for the Rpp29, Rpp30, and Pop5 expression constructs, M. L. S. Raj (Ohio State University) for the Mth P RNA clone; J. Reeve (Ohio State University) for Mth genomic DNA, M. Adams (University of Georgia, Athens) for Pfu genomic DNA; the Ohio State University Campus Chemical Instrument Center for mass spectrometric analyses; and the Ohio State University Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility and Plant Biotechnology Center for DNA sequencing. W.P.B. was supported by a National Institutes of Health Chemistry–Biology Interface training grant, and H.-Y.T. was supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship. This work was supported in part by Ohio State University and National Science Foundation Grants MCB-0092962 (to M.P.F.) and MCB-0091081 (to V.G.).

This work was presented in part at the Keystone Symposium on NMR in Molecular Biology, February 4–10, 2003, Taos, NM.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID code 1OQK).

Abbreviations: Mth, Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus; OB-fold, oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide-binding fold; ptRNA, precursor tRNA; HSQC, heteronuclear single quantum correlation; NOE, nuclear Overhauser effect.

Note Added in Proof. The solution structure of the Rpp29 homolog from Archaeoglobus fulgidus has recently been reported (60) and seems to adopt the same architecture as the Mth homolog.

References

- 1.Altman, S. & Kirsebom, L. (1999) in The RNA World, ed. Atkins, J. F. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 351–380.

- 2.Harris, M. E., Frank, D. N. & Pace, N. R. (1998) in RNA Structure and Functions, eds. Simons, R. W. & Grunberg-Manago, M. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), pp. 309–338.

- 3.Guerrier-Takada, C., Gardiner, K., Marsh, T., Pace, N. & Altman, S. (1983) Cell 35, 849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopalan, V., Baxevanis, A. D., Landsman, D. & Altman, S. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 267, 818–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niranjanakumari, S., Stams, T., Crary, S. M., Christianson, D. W. & Fierke, C. A. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 15212–15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurz, J. C., Niranjanakumari, S. & Fierke, C. A. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 2393–2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schedl, P. & Primakoff, P. (1973) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70, 2091–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eder, P. S., Kekuda, R., Stolc, V. & Altman, S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1101–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarrous, N. & Altman, S. (2001) Methods Enzymol. 342, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarrous, N. (2002) RNA 8, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao, S., Houser-Scott, F. & Engelke, D. R. (2001) J. Cell Physiol. 187, 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank, D. N. & Pace, N. R. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 153–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown, J. W. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall, T. A. & Brown, J. W. (2002) RNA 8, 296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kouzuma, Y., Mizoguchi, M., Takagi, H., Fukuhara, H., Tsukamoto, M., Numata, T. & Kimura, M. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306, 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith, D. R., Doucette-Stamm, L. A., Deloughery, C., Lee, H., Dubois, J., Aldredge, T., Bashirzadeh, R., Blakely, D., Cook, R., Gilbert, K., et al. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 7135–7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasserfallen, A., Nolling, J., Pfister, P., Reeve, J. & Conway de Macario, E. (2000) Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koonin, E. V., Wolf, Y. I. & Aravind, L. (2001) Genome Res. 11, 240–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews, A. J., Hall, T. A. & Brown, J. W. (2001) Biol. Chem. 382, 1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena, P. & Walker, J. R. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 1956–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkmann, U., Mattes, R. E. & Buckel, P. (1989) Gene 85, 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 23.Boomershine, W. P., Stephen Raj, M. L., Gopalan, V. & Foster, M. P. (2003) Protein Expression Purif. 28, 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris, J. K., Haas, E. S., Williams, D., Frank, D. N. & Brown, J. W. (2001) RNA 7, 220–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pannucci, J. A., Haas, E. S., Hall, T. A., Harris, J. K. & Brown, J. W. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7803–7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G. W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J. & Bax, A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, B. A. & Blevins, R. A. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavanagh, J., Fairbrother, W. J., Palmer, A. G., III, & Skelton, N. J. (1996) Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice (Academic, San Diego).

- 29.Sattler, M., Schleucher, J. & Griesinger, C. (1999) Progr. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 34, 93–158. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay, L. E., Torchia, D. A. & Bax, A. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8972–8979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., et al. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornilescu, G., Delaglio, F. & Bax, A. (1999) J. Biomol. NMR 13, 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski, R. A., Rullmannn, J. A., MacArthur, M. W., Kaptein, R. & Thornton, J. M. (1996) J. Biomol. NMR 8, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grzesiek, S., Bax, A., Clore, G. M., Gronenborn, A. M., Hu, J. S., Kaufman, J., Palmer, I., Stahl, S. J. & Wingfield, P. T. (1996) Nat. Struct. Biol 3, 340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murzin, A. G. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 861–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theobald, D. L., Mitton-Fry, R. M. & Wuttke, D. S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32, 115–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazantsev, A. V., Krivenko, A. A., Harrington, D. J., Carter, R. J., Holbrook, S. R., Adams, P. D. & Pace, N. R. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7497–7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzfaden, C., Nicholson, N., Jones, J. J., Guth, S., Lehr, R., Prescott, C. D., Hegg, L. A. & Eggleston, D. S. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 295, 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stams, T., Niranjanakumari, S., Fierke, C. A. & Christianson, D. W. (1998) Science 280, 752–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chamberlain, J. R., Lee, Y., Lane, W. S. & Engelke, D. R. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 1678–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chu, S., Zengel, J. M. & Lindahl, L. (1997) RNA 3, 382–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarrous, N., Eder, P. S., Wesolowski, D. & Altman, S. (1999) RNA 5, 153–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarrous, N., Reiner, R., Wesolowski, D., Mann, H., Guerrier-Takada, C. & Altman, S. (2001) RNA 7, 1153–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Eenennaam, H., Lugtenberg, D., Vogelzangs, J. H., van Venrooij, W. J. & Pruijn, G. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31635–31641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Draper, D. E. & Reynaldo, L. P. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 381–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dabrowski, S., Olszewski, M., Piatek, R., Brillowska-Dabrowska, A., Konopa, G. & Kur, J. (2002) Microbiology 148, 3307–3315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li, W. & Hoffman, D. W. (2001) Protein Sci. 10, 2426–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitton-Fry, R., Anderson, E. M., Hughes, T. R., Lundblad, V. & Wuttke, D. S. (2002) Science 296, 145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nonato, M. C., Widom, J. & Clardy, J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17057–17061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holbrook, J. A., Tsodikov, O. V., Saecker, R. M. & Record, M. T., Jr. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 310, 379–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spolar, R. S. & Record, M. T., Jr. (1994) Science 263, 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ban, N., Nissen, P., Hansen, J., Moore, P. B. & Steitz, T. A. (2000) Science 289, 905–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wimberly, B. T., Brodersen, D. E., Clemons, W. M., Jr., Morgan-Warren, R. J., Carter, A. P., Vonrhein, C., Hartsch, T. & Ramakrishnan, V. (2000) Nature 407, 327–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houser-Scott, F., Xiao, S., Millikin, C. E., Zengel, J. M., Lindahl, L. & Engelke, D. R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2684–2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang, T. & Altman, S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 920–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang, T., Guerrier-Takada, C. & Altman, S. (2001) RNA 7, 937–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Risler, J. L., Delorme, M. O., Delacroix, H. & Henaut, A. (1988) J. Mol. Biol. 204, 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koradi, R., Billeter, M. & Wuthrich, K. (1996) J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sidote, D. J. & Hoffman, D. W. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 13541–13550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]