Abstract

Nakao and colleagues demonstrate that carbon monoxide added to organ preservation solution reduces donor-kidney injury that occurs after cold storage and transplantation and improves the survival of the recipient. These findings are important because they highlight the role of the cytochrome P450 system in the pathogenesis of donor-kidney injury and they suggest a strategy for preserving the donor kidney, namely, the addition of carbon monoxide to organ preservation solution.

Carbon monoxide (CO) possesses a high affinity for the heme prosthetic group, the latter representing a defining motif for a family of ubiquitous and functionally diverse proteins. Such binding may markedly impair the function of these proteins, and for heme proteins that subserve a vital function, the consequences can be lethal. For example, the affinity of CO for hemoglobin is more than 200 times greater than that of oxygen, and in sufficiently high concentrations, CO vitiates the oxygen-carrying capability of hemoglobin and thereby compromises the oxygenation of tissues. Through these and other effects, CO can cause acute and chronic toxicity, and, indeed, environmental exposure to CO is one of the commonest causes of accidental poisoning in the United States, and a cause for considerable and appropriate public concern.

Viewed from this perspective, it may come as a surprise that CO added to organ preservation solution can improve the function of the transplanted kidney and the survival of the recipient. Yet these remarkable findings are described in an important study by Nakao et al.1 (this issue). In addition to suggesting a strategy for organ preservation, these findings of Nakao et al.1 are a significant step in the steady procession of experimental studies demonstrating the remarkable cytoprotective properties of CO when it is present in relatively low concentrations.2–4 The initial demonstration that induction of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) can confer a protective response against tissue injury stimulated interest in HO-1 as a cytoprotective molecule, and in identification of the specific HO product and downstream effect of the induction of HO-1 that are responsible for such cytoprotection.5 Initially, attention was directed to the synthesis of ferritin (an antioxidant, iron-binding protein) and the production of bile pigments (antioxidant metabolites) as potential mechanisms.5 CO, the other main product of HO activity, while recognized as a vasorelaxant molecule and incriminated as a signaling species, was not considered, at the time, a cytoprotective molecule. This salutary property of CO was shown in 1999 in a landmark study that demonstrated that CO, at relatively low concentrations (50–500 parts per million), protected against hyperoxia-induced lung injury by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis.6 These findings presaged a groundswell of investigations demonstrating the beneficial effects of CO (when present in such low concentrations) in diverse models of tissue injury, and which reflected, depending on the disease model, any one or combination of the following properties of CO: antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, immune-suppressant, antithrombotic, angiogenic, antifibrotic, and vasorelaxant.2–4,7,8 Moreover, such protection was conferred not only by CO administered as a gas but also by novel CO-releasing compounds.3

The cytoprotective properties of HO-1 were rapidly explored in the field of transplantation and were observed to mitigate ischemia/reperfusion injury of the transplanted kidney, acute renal allograft rejection, and chronic allograft nephropathy; these protective effects were recapitulated, in part, by products of HO such as CO and/or bile pigments.7,8 Attention was also directed to organ preservation, an issue of central importance in this field, and one renewed by the increasing use of marginal donor organs. From the moment of harvesting, the kidney and other donor organs are subjected to a series of stresses. Deprived of its blood supply at the time of procurement, flushed with a cold, artificial solution, and maintained in the cold for variable periods, and then subjected to rewarming, reoxygenation, and reperfusion, the kidney is nonetheless expected to successfully negotiate each of these phases such that its vitality and function are preserved when it is transplanted into the recipient. Failure to adequately withstand the stresses imposed by each phase may increase, in the short term, the risk for delayed graft function and acute cellular rejection, and in the long term, the risk for chronic allograft nephropathy. Considerable effort is thus understandably directed to optimizing solutions used for organ preservation.

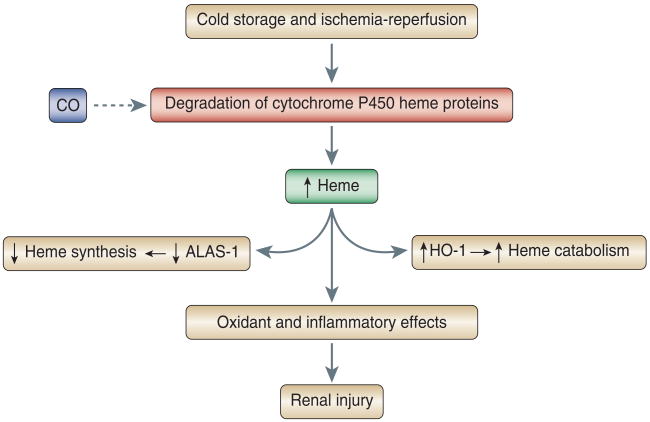

Using an orthotopic kidney transplant model, Nakao et al.1 demonstrated that the use of a CO-containing preservation solution diminished oxidative injury and the upregulation of inflammatory participants in the kidney as assessed 3 hours after transplantation; improved renal function and reduced histologic injury at 1 month after transplantation; and enhanced survival of the recipients of these kidneys over 100 days of observation in the post-transplantation period. To explore the basis for these effects, the authors drew on the long-recognized observation that in injured tissues, destabilization of heme proteins can occur such that heme is released from the protein moiety to which it is bound. Heme, in its free, unfettered form, and in sufficient amounts, is toxic by virtue of its lipophilic, prooxidant, proinflammatory, and pro-apoptotic properties. Heme proteins vary with regard to the ease with which heme can be freed from its linkage with protein, and cytochrome P450 heme proteins are among those considered more likely to do so. Cytochrome P450 heme proteins are abundant in the kidney, where they facilitate the metabolism of endogenous and exogenous substances; in models of ischemic renal injury, they are denatured and contribute to kidney injury by releasing heme or iron, either of which can promote oxidative stress. In the present study by Nakao et al.,1 the addition of CO to the preservation fluid prevented the marked increase in kidney heme content and the degradation of kidney cytochrome P450 observed in the transplanted kidney and assessed 3 hours after the onset of reperfusion. That heme content was increased in the kidneys exposed to the control preservation solution and decreased when such solutions contained CO was corroborated by the observed changes in expression of HO-1 and 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase-1 (ALAS-1): it is well established that the rate-limiting enzyme in heme degradation (HO-1) is induced, and the rate-limiting enzyme in heme synthesis (ALAS-1) is suppressed, when tissue content of heme is increased. The authors thus suggest that, following the stress of cold preservation and transplantation, cytochrome P450 heme proteins undergo denaturation and the release of heme, the latter inducing renal injury because of its prooxidant and proinflammatory effects; CO, when added to the preservation solution, binds to cytochrome P450 enzymes, thereby stabilizing them and preventing their oxidative denaturation and the attendant increments in kidney heme content (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms underlying donor-kidney injury and the protective effect of carbon monoxide.

The dashed arrow indicates an inhibitory effect of carbon monoxide on the degradation of cytochrome P450 heme proteins. Abbreviations: CO, carbon monoxide; ALAS-1, 5-aminolevulinic acid synthase-1; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1.

This pathway provides a plausible explanation for the observed findings. Germane considerations raised by these findings include the fate of redox-active iron in the donor kidney and the possibility that redox-active iron in the donor kidney may contribute to kidney injury. It is also possible that oxidative stress during the phase of reoxygenation/reperfusion may be a cause, as well as a consequence, of destabilization of cytochrome P450. Furthermore, the protective effects of CO may also reside in mechanisms that are upstream of, or do not directly involve, stabilization of cytochrome P450. Interestingly, CO can promote as well as diminish oxidant stress,9 and either effect of CO may be relevant to cytoprotection. For example, by interacting with heme contained in NADPH oxidase, CO can diminish oxidant generation from this source. Conversely, by interacting with heme contained in mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase, CO can inhibit mitochondrial electron transport, and such inhibition of electron transport, as is well established, promotes the generation of oxidants. An intriguing question is whether low-grade oxidant generation in the donor kidney, induced by CO during cold storage, may condition the kidney so as to render the organ resistant to the surge of oxidative stress expected during the phase of reoxygenation/reperfusion. Irrespective of the mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of CO, the significance of the study of Nakao et al.1 is that it provides a CO-based strategy for kidney preservation, one that is applicable to other organs,7 and one that may also be proffered by CO-releasing molecules.3

In his brilliant analysis, Taleb uses the phrase ‘black swan’ to designate those unusual phenomena that turn out to be highly influential and consequential, and yet were neither predicted nor anticipated.10 Viewed from the clinical and environmental perspective of CO as an invariant and potentially lethal toxicant, it would never have been predicted that, in much lower amounts, CO may be a protectant. Although the challenges in realizing the therapeutic potential of CO are huge and include the bedeviling truth that, in increasing concentrations, CO is transformed from a protectant to a toxicant, nonetheless, the prospect that CO affords a therapeutic strategy for human disease carries, unquestionably, a high impact. CO as a therapeutic agent thus appears as a black swan. That such an exciting prospect exists is an indubitable testament to the importance of the initial demonstration of the cytoprotective properties of CO, the illuminating evidence that followed, and the present findings of Nakao et al.1 demonstrating that CO may assist in preserving the donor kidney.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The author declared no competing interests.

References

- 1.Nakao A, Faleo G, Shimizu H, et al. Ex vivo carbon monoxide prevents cytochrome P450 degradation and ischemia/reperfusion injury of kidney grafts. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dulak J, Deshane J, Jozkowicz A, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in vascular pathobiology: focus on angiogenesis. Circulation. 2008;117:231–241. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foresti R, Bani-Hani MG, Motterlini R. Use of carbon monoxide as a therapeutic agent: promises and challenges. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:649–658. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraham NG, Kappas A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:79–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GM, et al. Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid, protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:267–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI115847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otterbein LE, Mantell LL, Choi AM. Carbon monoxide provides protection against hyperoxic lung injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L688–L694. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakao A, Choi AM, Murase N. Protective effect of carbon monoxide in transplantation. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:650–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soares MP, Bach FH. Heme oxygenase-1 in organ transplantation. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4932–4945. doi: 10.2741/2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boczkowski J, Poderoso JJ, Motterlini R. CO-metal interaction: vital signaling from a lethal gas. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taleb N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. 1st. Random House; New York: 2007. p. 366. [Google Scholar]