Abstract

Objective

To provide a synopsis of past, current, and potential next-generation approaches to prevention for positives (PfP) interventions in the United States.

Findings/Summary

For a variety of reasons, PfP interventions, with the goals of limiting HIV transmission from people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) to others, and protecting the health of PLWHA, did not appear with any frequency in the United States until about 2000. Even today, the number and breadth of evidence-based PfP interventions is very limited. Nevertheless, meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that such interventions can be effective, perhaps even more so than interventions targeting HIV-uninfected individuals.

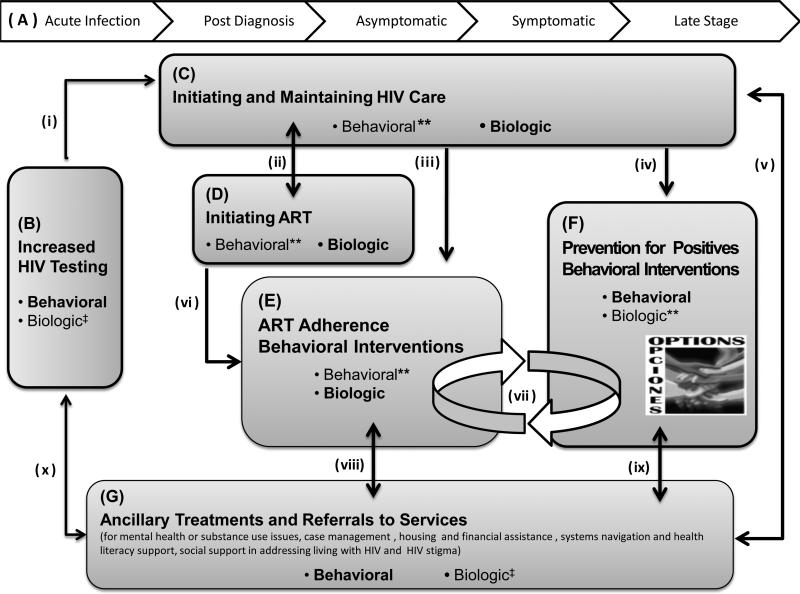

We review early and more recent PfP interventions and suggest that next-generation PfP interventions must involve behavioral and biologic components and target any element that affects HIV risk behavior and/or infectivity. Next generation PfP should include increased HIV testing to identify additional PLWHA, components to initiate and maintain HIV care, to initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) and promote adherence, and to reduce sexual and injection drug use risk behavior, as well as ancillary treatments and referrals to services. Comprehensive next-generation PfP, including all of these elements and effective linkages among them, is depicted in Figure 1.

Keywords: Positive prevention, secondary prevention of HIV, prevention for positives interventions, HIV prevention, people living with HIV (PLWHA), behavioral-biologic interventions

INTRODUCTION

Prevention for positives (PfP) interventions are supportive prevention efforts administered to people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and tailored to their needs. They involve behavioral and biologic strategies (see components B–G, Figure 1) that can benefit the public health by limiting HIV transmission to others, and at the same time, can protect the health of PLWHA by lowering their likelihood of acquiring other pathogens.1–4 The rationale for PfP interventions as a critical element of HIV prevention involves the fact that all “new” HIV infections must begin with an HIV positive individual, and the finding that some PLWHA who are aware of their antibody status continue to practice risky behavior.5–9 For these reasons, from an HIV prevention perspective, it can be highly efficient to intervene with PLWHA,3,10 and highly effective.1,11,12 Strengthening this argument is that, since large numbers of PLWHA are on ART, HIV prevalence in the United States will continue to rise,3,13 along with the number of individuals capable of transmitting HIV, and even drug resistant HIV, through risky behavior.1,3

Figure 1.

A comprehensive approach to next-generation prevention for positives. (Degree of evidence supporting behavioral and/or biologic transmission risk: Bold face denotes that there is substantial evidence, ** emerging evidence, or ‡ limited to no support.)

About 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV,13,14 75% to 80% of whom are aware of their antibody status.13,15,16 About one third of these PLWHA continue to engage in risk behaviors that can transmit HIV to others.5–9 Reasons vary widely and include dynamics such as lack of critical information, motivation, and behavioral skills needed to practice safer behaviors, alcohol and drug use, mental health issues, extreme poverty, and intimate partner violence, among others. These have been reviewed elsewhere.1,17–20

Despite a critical need, PfP interventions were rare until 2 decades into the US epidemic.21 The delay in funding and addressing the prevention needs of PLWHA likely occurred because US policy was late in prioritizing this issue. For reasons synthesized in a recent article,21 policies and programmatic approaches highlighting the importance of PfP emerged only circa 2000.22–24

A review paper in 2000 described PfP as a “new issue.”25,26 In fact, to date, the vast majority of HIV prevention interventions in the United States have not focused on the HIV prevention needs of PLWHA. Literally hundreds of HIV prevention intervention studies and many meta-analytic reviews of this work have been published, and almost all of the populations targeted in this work were selected for characteristics other than serostatus.11,21,27 As reported in W. Fisher,21 of fully 898 HIV prevention interventions between 1988 and 2006 identified in a research synthesis project database of the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC), only 6.6% were directed at PLWHA, most occurring after 2000. The overall dearth of evidence-based PfP interventions is also manifest in the very small number of such interventions identified by the CDC as “best” or “promising evidence” and targeted for widespread dissemination.21 This is the case despite strong arguments that PfP interventions, which focus, in part, on serostatus and its effect on HIV risk and preventive behavior, are a critical component of an effective, comprehensive approach to HIV prevention.1,3,10,21,23,28,29

EARLY PFP INTERVENTIONS

The first 2 meta-analytic reviews of PfP interventions were conducted on trials published before early 2005 and involved outcomes on sexual risk behavior,11,12 sexually transmitted infections (STI),11 and drug use risk behavior.11 Eighteen distinct interventions, meeting strict criteria, were included in these meta-analyses. All but 2 interventions were conducted exclusively within the United States and 14 exclusively targeted PLWHA. Across both meta-analyses, PfP interventions effectively reduced sexual risk, particularly instances of unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse, and did so more effectively than earlier interventions with seronegative populations. Crepaz et al11 also found that PfP interventions targeting biologic end points were effective in reducing STI incidence. However, significant reductions were not observed in number of sex partners12 and in needle-sharing outcomes.11 Nevertheless, Crepaz et al11 concluded that the overall magnitude of sexual risk reduction observed across all interventions and end points reviewed implied that PfP would likely be cost-effective in terms of larger-scale health benefits. Meta-analyses also identified specific PfP intervention elements with respect to intervention design (eg, theoretically based; individual vs group level), content, delivery (eg, by a health care provider or professional counselor), and population characteristics, related to more effective outcomes.11,12

Our own program of PfP research, the Options Project, was funded by NIMH in 1999 to develop, implement, and rigorously evaluate a PfP intervention delivered by HIV-care providers with PLWHA in a clinical care setting. It was based on the Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of HIV risk and prevention.30–32 In terms of the model, HIV risk behavior in PLWHA, and others, is often associated with weaknesses in individuals’ levels of HIV prevention IMB. Individual-level PfP interventions, which address these elements, should lead to sustained increases in HIV prevention. Options involved having providers assess the IMB dynamics of patients’ HIV risk behavior and intervene to remediate any weaknesses. US studies revealed that these brief interventions, embedded in regular patient care, led to significant and sustained changes in patient risk behavior.10,28

MORE RECENT PFP INTERVENTIONS

Since the two 2006 meta-analyses, additional PfP intervention trials have been published. Two descriptive reviews published in 2009 identified 7 new intervention outcome studies and 14 characterizations of interventions under development or investigation. Across both reviews, PfP interventions continued to be effective across a variety of intervention design and delivery processes.1,33

Table 1 summarizes all US PfP interventions with behavioral or biologic outcomes conducted, evaluated, and published between January 1, 2005 (the approximate cutoff for the two 2006 meta-analyses), and July 13, 2010. We utilized all search terms1 provided in all previous reviews.1,11,12,33 Eighteen PfP interventions reporting behavioral or biologic outcomes10,34–50 are depicted in Table 1. Twenty-seven additional studies were identified reporting intermediate, prebehavioral outcomes (eg, information, self-efficacy)51–53 or characterizing intervention development and implementation processes.29,54–76 All were identified through searches in PubMed, Psych Info, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), and the previous reviews.

Table 1.

US Prevention for Positives Interventions Published in English, Reporting Behavioral or Biologic Transmission Risk Outcomes between January 1, 2005, and June 13, 2010

| STUDY Setting(s) Target Population Project Name (Date) |

INTERVENTION DESIGN Level of Intervention Intervention Delivery Intensity–Duration |

INTERVENTION DESCRIPTION Intervention Goal Theory Intervention Group (G) and Comparison Group (CG) Brief Descriptions |

OUTCOMES Direction and Significance of outcomes in IG vs CG (Behavioral, Biomedical, and Psychosocial Variables) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Coleman et al (2009)34 Setting: Classroom-like setting Population†: PLWHA (age ≥ 50); African American MSM; CLN, COMM Project: No name (2006–2007) |

RCT (2 arm), feasibility pilot test Level: Group Delivery: By group facilitators, Cog–Behavioral techniques Intensity–Duration: 4 sessions (120 min ea); 1 mo duration; last FU 3 mo |

Goal: Increase proportion of consistent condom use for each anal sex act Theory: SCT, TRA, TPB IG (n = 30): Taught condom negotiation skills with role-play and contextual risk negotiation, provided health-focused information CG (n = 30): Time-and-attention–matched, health-focused control arm |

Sex outcomes ↑Consistent condom use total sample: Observed in both arms, slight trend in IG arm ↑Consistent condom use if inconsistent at BL: Trend ↓ Proportion of MSM with multiple partners: Trend |

|

Fisher et al (2006)10 Setting: 2 HIV clinics Population: PLWHA, CLN Project: Options/Opciones (2000–2003) |

Quasi-experimental (2 arms) Level: Individual Delivery: By HIV providers during routine care visits; MI approach Intensity–Duration: ~ 6 sessions (5–10 min ea); 18 mo duration; last FU 18 mo |

Goal: Reduce UVA/O through brief, ongoing risk reduction counseling Theory: IMB IG (n = 252)‡: Patient-centered conversations around sex or drug use behaviors; assess readiness to address risk behaviors, provide risk reduction strategy options, develop tailored risk reduction goal CG (n = 245)‡: Standard of care, risk counseling at providers’ discretion |

Sex outcomes ↓ UVA/O all partners: SIG ↓ UVA/O HIV-/? partners: Trend ↓ No. of HIV- /? partners: Trend Drug outcomes Low response rate, not analyzed |

|

Gardner et al (2008)35 Setting: 7 HIV clinics Population†: PLWHA, CLN Project: Positive Steps (2005–2006) |

Pre–post (1 arm); demonstration project Level: Individual Delivery: By HIV providers during routine care visits Intensity–Duration: ~ 3 sessions (~ 3 min ea); 12 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Evaluate reduced risk of transmission in multiclinic study Theory: N/A IG (n = 767)‡: Screen for risk, deliver risk reduction messages, and create risk reduction plan with providers; provide supplemental brochures and posters CG: N/A; longitudinal cohort, with only participants who had data at all time points included in analysis |

Sex outcomes ↓ UVA all partners: SIG ↓ UVA HIV-/? partners: SIG ↓ UVA HIV+ partners: SIG Drug outcomes Low response rate, not analyzed STI outcomes Low BL prevalence, not analyzed |

|

Gilbert et al (2008)36 Setting: 5 HIV clinics Population†: PLWHA, CLN Project: Positive Choice (2003–2006) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Individual Delivery: By computers during routine care visits; MI approach Intensity–Duration: 2 sessions (~ 24 min ea); 3 mo duration; last FU 6 mo |

Goal: Reduce illicit drug use, risky alcohol consumption, and UVA Theory: N/A IG (n = 243): Computer-based risk assessment preceding a tailored “Video Doctor” risk reduction counseling session; printout of behavioral assignment and referrals for substance use and harm-reduction services CG (n = 233): Computer-based risk assessment, followed by standard of care, risk counseling at providers’ discretion |

Sex outcomes ↓ UVA: SIG ↑ Condom use all partners: Trend observed in both arms, no difference between arms ↓ No. casual partners: SIG# Drug outcomes ↓ Drug use: SIG ↓ Mean days of ongoing drug use: Trend ↓ Alcohol risk: Observed in both arms, no difference between arms |

|

The Healthy Living Project (2007)37 Setting: 4 sites (HIV clinic, research, and community service sites) Population†: PLWHA, CLN, COMM Project: The Healthy Living Project (2000–2004) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Individual Delivery: By facilitators; Cog–Behavioral techniques Intensity–Duration: 15 sessions (90 min. ea); 5 mo duration; last FU 25 mo |

Goal: Reduce number of sex-related risk acts with HIV-/? partners, execute effective coping responses, enhance adherence with PLWHA ≤ 85% adherent at BL Theory: Social Action Theory IG (n = 467)‡: 3 modules focused on stress, coping, and adjustment; reducing transmission risk behaviors; enhancing health promotion via adherence to medical care and ART CG (n = 469)‡: Wait-list control comparison group |

Sex outcomes ↓ Mean no. sex risk acts with HIV-/? partners: SIG# ↓ No. sex risk acts with HIV-/? partners from BL: Observed in both arms, no difference between arms Adherence outcomes ↑ Adherence in nonadherers at BL: SIG# Psychosocial outcomes Changes in psychosocial adjustment: NS Changes in psychosocial adjustment among PLWHA with depressive symptoms at BL: NS |

|

Illa et al (2010)38 Setting:1 HIV clinic Population†: PLWHA (age ≥ 45); CLN Project: Project ROADMAP (2004–2006) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Group Delivery: Based on Project INSPIRE45 Intensity–Duration: 4 sessions (1–2.5 hr ea); intervention duration NR; last FU 6 mo |

Goal: Target sexual risk reduction in older PLWHA Theory: IMB, Self-Efficacy Theory IG (n = 149)‡: Tailored psychoeducational group sessions to address HIV, its effects on sexual behaviors, and harm reduction approaches; safer-sex negotiation skills and strategies for older PLWHA CG (n = 92): Received educational brochure, followed by standard of care |

Sex outcomes ↓ UVA all partners: SIG ↓ UVA HIV-/? partners: SIG ↓ UVA HIV+ partners: NS Psychosocial outcomes ↑ HIV knowledge: Observed in both arms, no difference between arms ↑ Sexual self-efficacy: NS |

|

Lightfoot et al (2010)39 Setting: 6 HIV clinics Population: PLWHA, CLN Project: No name (2001–2004) |

Quasi-experimental (3 arms) Level: Individual Delivery: By computer or HIV provider/staff during routine care visits; FRAMES Intensity–Duration: ≤ 11 sessions (10 min ea computer, 5–15 min ea providers); 30 mo duration; last FU 30 mo |

Goal: Provide brief risk reduction intervention to enhance motivation and encourage PLWHA to act in accordance with their values Theory: N/A IGs 2 intervention conditions: Computer-delivered arm (IG-1, n = 325)‡; provider-delivered arm (IG-2, n = 209)‡; assess/provide feedback on behavior and personal values; enhance self-efficacy and behavior change CG (n = 229)‡: Standard of care provided in control comparison clinics |

Sex outcomes ↓ No. of HIV-/? partners: SIG (IG-1 compared to IG-2 and CG arms) ↓ UVA HIV-/? partners: SIG (IG-1 compared to CG arm) |

|

Margolin et al (2007)40 Setting: 1 methadone clinic Population: PLWHA, methadone-maintained drug users, COMM Project: 3-S+ Therapy (dates NR) |

Quasi-experimental, pre–post (2 arm) Level: Individual Delivery: Therapist-led; Cog–Behavioral and Buddhist psychologies Intensity–Duration: 12 sessions (session time NR); 3 mo duration; last FU 3 mo |

Goal: Increase motivation for abstinence, HIV prevention, and medication adherence; decrease impulsivity in HIV-positive drug-using population Theory: Cognitive Self Schema Theory, Buddhist principles IG (n = 21)‡: Weekly therapy focused on replacing addict self-schema with a spiritual self-schema; and on increasing awareness of addiction and its impact on adherence, risk, and HIV care behaviors CG (n = 17)‡: Standard-of-care methadone-maintenance therapy; nonrandomized; participants elected to complete preassessments and postassessments only |

HIV risk outcomes (low response rate) ↓HIV transmission risk behaviors: NS Drug outcomes ↓ Intoxicant use: Trend ↑ Motivation for drug abstinence: SIG Psychosocial outcomes ↓Impulsivity: SIG ↑ Mean influence of spirituality on motivation for health-promoting behaviors: SIG |

|

Mausbach et al (2007)41 Setting: NR Population†: PLWHA, MSM who use methamphetamines, CLN, COMM Project: EDGE (1999–2004) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Individual Delivery: Therapist-led; MI approach Intensity–Duration: 8 sessions (90 min ea); 3 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Increase safer sexual behaviors in presence of methamphetamine use Theory: SCT, TRA IG (n = 170)‡: Targeted skills training and problem solving to enhance knowledge and self-efficacy with condom use/negotiation; serostatus disclosure to partners in context of ongoing substance use CG (n = 171)‡: Time–attention control diet and exercise sessions |

Sex outcomes ↓ Total UVA over time: NS ↑ Proportion protected sex acts: SIG ↑ No. protected sex acts over time: SIG Psychosocial outcomes ↑ Self-efficacy condom use: SIG ↑ Self-efficacy condom negotiation: observed in both arms, no difference between arms |

|

Mitchell et al (2007)42 Setting: 1 HIV clinic Population: PLWHA, marginally housed, substance-using, CLN Project: DAART+ (2003–2006) |

Pre–post (1 arm), feasibility pilot Level: Individual Delivery: By case managers; strengths-based approach Intensity–Duration: Daily mDOT sessions tapered to biweekly, then monthly; 12 mo duration; last FU 3–6 mo |

Goal: Support adoption and maintenance of medication adherence and HIV risk reduction behaviors Theory: TTM Stages of Change, IMB IG (n = 30)‡: Integrated discussions on adherence barriers and current sex and substance-use behaviors in the context of mDOT CG: N/A; longitudinal cohort, with no comparison group available |

Sex and drug outcomes (low response rate) ↓ Sexual and substance-using risk behaviors: NS Viral load outcomes Viral load data for participants with final assessment (n = 18), 83% achieved viral suppression |

|

Naar-King et al (2009)43 Setting: 5 HIV clinics Population†: PLWHA (aged 16–24), multiple risk factors, CLN Project: Healthy Choices (2005–2007) |

RCT (2 arm) Level: Individual Delivery: Therapist-led; MI approach Intensity–Duration: 4 sessions (60 min ea); 2.5 mo duration; last FU 9 mo |

Goal: Enhance viral response in young PLWHA with multiple transmission–related risk behaviors Theory: N/A IG (n = 94): MI sessions to address two risk factors (eg, nonadherence; sex or drug risk) and access to enhanced support services for sexual risk, drug use, mental health, and medication adherence CG (n = 92)‡: Standard of care, access to enhanced support services |

Viral load outcomes ↓ Viral load: SIG# |

|

Petry et al (2010)44 Setting: HIV drop-in center Population: PLWHA, cocaine or opioid dependent diagnosis, COMM Project: No name (2003–2007) |

RCT (2 arm) Level: Group Delivery: Therapist-delivered Intensity–Duration: 24 sessions (60 min ea); 6 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Assess efficacy of contingency-based rewards on supporting and sustaining both health and substance use reduction behaviors Theory: N/A IG (n = 89): Support group with contingency-based rewards provided for substance use abstinence and completion of health enhancement components; integrated support and substance use reduction messages CG (n = 81): 12 Step–based group support, abstinence messages |

Sex outcomes ↓ Sexual risk scores: SIG# Drug outcomes ↓ Drug risk scores: NS ↑ No. consecutive drug-free urine tests: SIG ↑ Proportion drug-free urine tests: NS Viral load outcomes ↓Viral load: SIG# |

|

Purcell et al (2007)45 Setting: 4 community health centers Population†: PLWHA, IDU, COMM Project: INSPIRE (2001–2005) |

RCT (2 arm) Level: Individual, group Delivery: By paraprofessionals Intensity–Duration: 10 sessions (session time NR); 1.25 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Reduce sexual and injection risk behaviors, increase utilization of HIV care and adherence to ART Theory: SLT, Social Identity Theory, IMB IG (n = 486): Focus on motivation/skills for increasing use of HIV care, for adherence, and for reducing sex and drug risk behaviors through developing new social role as a peer–mentor CG (n = 480): Discuss videos focusing on information for HIV-infected IDU |

Sex and injection-drug outcomes ↓ Sex and injection risk: Observed in both arms, no difference between arms Health care utilization outcomes ↑ Care utilization: NS Adherence outcomes ↑ Adherence: NS |

|

Rosser et al (2010)46 Setting: 6 community sites Population†: PLWHA, MSM, CLN, COMM Project: Positive Connections (2005–2008) |

RCT (3 arms) Level: Group Delivery: By HIV+ MSM-identified or MSM-identified health professional facilitators (matched to intervention arm) Intensity–Duration: 1 session (14–16 hr); 1 weekend long; last FU 18 mo |

Goal: Reduce frequency of serodiscordant UAI Theory: Sexual Health Model IGs across 2 arms: Health seminars identified and address sexual health and HIV risk concerns from an HIV+ MSM (IG-1, n = 248)‡ or general, serostatus-neutral, MSM (IG-2, n = 237)‡ perspective CG (n = 190)‡: Viewed and evaluated MSM HIV prevention–focused DVDs |

Sex outcomes ↓ Frequency of serodiscordant UAI: observed in all 3 arms, no difference between arms Psychosocial outcomes ↑ Intentions to avoid high-risk behaviors: SIG# (IG-1 and IG-2 arms) |

|

Serovich et al (2009)47 Setting: NR Population: PLWHA, MSM, COMM Project: No name (dates NR) |

Randomized control, crossover design (3 arms); pilot study Level: Individual Delivery: By facilitator, or computer and facilitator Intensity–Duration: 4 sessions (session time NR); 1 mo duration; last FU 3 mo |

Goal: Reduce UAI and enhance disclosure to casual partners in MSM Theory: Consequences Theory of Disclosure IGs 2 intervention conditions: One with facilitator risk assessment and facilitator delivery (IG-1, n=40)§, the other with computer risk assessment and facilitator delivery (IG-2, n=37)§; both assessed cost and benefits of disclosure and disclosure triggers and strategies CG (n = 21)§: Wait-list control condition |

Sex outcomes (small sample size, low response rate CG) ↓ Mean frequency of UAI all partners: NS; increased odds of UAI observed in both IG-1 and IG-2 compared to CG arm, despite a reduction in UAI over time in IG-1 arm Disclosure outcomes ↑ Favorable disclosure attitudes: SIG (IG-1 arm) ↑ Favorable disclosure behaviors: Trend (IG-1 arm) ↑ Favorable intentions to disclose: NS |

|

Sikkema et al (2008)48 Setting: 1 community health center Population: PLWHA, childhood sexual abuse–related trauma, CLN, COMM Project: LIFT (2002–2004) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Group Delivery: By cotherapists; Cog–Behavioral and coping strategies Intensity–Duration: 15 sessions (90 min ea); 3.75 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Improve coping and reduce sexual risk behavior in PLWHA with childhood sexual abuse history Theory: Cognitive Theory of Stress and Coping IG (n = 124)‡: Taught adaptive coping and problem-solving strategies to identify individual triggers and select goals; skills building for dealing with sexual abuse–related trauma and risk reduction CG (n = 123)‡: Time-matched HIV support group comparison condition |

Sex outcomes ↓ UAV all partners: SIG ↓ UAV HIV-/? partners: SIG |

|

Teti et al (2010)49 Setting: 1 HIV clinic Population: PLWHA, women, CLN Project: Protect and Respect (2004–NR) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Individual, group Delivery: 3 components (by HIV providers during routine care visits, health educators, HIV+ peers) Intensity–Duration: Provider sessions (3–5 min ea), health education group 5 sessions (1.5 hrs/wk), optional peer support group (1 hr/wk); 1.25 mo duration; last FU 18 mo |

Goal: Support HIV+ women in decreasing UVA and other sexual risks; increase serostatus disclosure to partners Theory: TTM Stages of Change, Modified AIDS Risk Reduction Model, Theory of Gender and Power IG (n = 92)‡: Brief risk reduction conversation with HIV providers; health educator–led group sessions for sexual risk reduction education and skills building; weekly HIV+ peer-led support group to discuss skills CG (n = 92)‡: Standard of care; brief provider risk-reduction messages |

Sex outcomes ↑ Condom use during vaginal/anal intercourse: Trend Disclosure outcomes ↑ Proportion of partners disclosed serostatus to: SIG# ↑ Total no. partners disclosed serostatus to: NS |

|

Velasquez et al (2009)50 Setting: NR Population†: PLWHA, MSM with diagnosed alcohol use disorder, COMM Project: Positive Choices (1999–2003) |

RCT (2 arms) Level: Individual, group Delivery: By therapist and HIV+ MSM group facilitators; MI approach Intensity–Duration: 8 sessions (session time NR); 2 mo duration; last FU 12 mo |

Goal: Reduce both alcohol use and unprotected sexual behaviors Theory: TTM Stages of Change and Processes of Change IG (n = 118)‡: Individual therapy sessions enhanced motivation and skills to change alcohol, sexual behavior; peer support group sessions focused on HIV risk reduction and safer sexual behaviors CG (n = 135)‡: Resource referral control condition |

Sex and drinking outcomes ↓ No. days with both UAI and heavy drinking: SIG# Drinking outcomes ↓ No. drinks in past 30 days: SIG# ↓ No. heavy drinking days in past 30 days: SIG# |

* STUDY: PLWHA denotes adults living with HIV aged 18 or older, unless otherwise noted; CLN, HIV medical clinic–based sample; COMM, community-based sample; IDU, injection drug users; NR, information not reported in manuscript. INTERVENTION DESIGN: ea, each; mo, months; min, minutes; FU, follow-up; Cog–Behavioral, cognitive-behavioral intervention delivery techniques; MI, motivational interviewing intervention delivery techniques; FRAMES, Feedback–Responsibility–Advise–Menu of Options–Empathy–Self-Efficacy; mDOT, Modified Directly Observed Therapy. INTERVENTION DESCRIPTION: IG, intervention group; CG, comparison group; BL, baseline assessment; SCT, Social Cognitive Theory; TRA, Theory of Reasoned Action; TPB, Theory of Planned Behavior; IMB, Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills Model; TTM, Transtheoretical Model; SLT, Social Learning Theory. OUTCOMES: Trend, a nonsignificant trend was observed in the IG; UAI/UVA/UVAO, unprotected anal, vaginal–anal, vaginal–anal–oral intercourse; HIV-/?, HIV negative or status unknown; SIG, changes in outcomes between the IG and CG were significant (p ≤ 0.05); NS, changes in outcome between IG and CG were nonsignificant (p ≤ 0.05).

Participants were screened for recent history of risk behaviors and/or sexual activity.

Attrition rates > 20% as reported or calculated based on sample size reported at BL and last FU.

Sufficient information to calculate attrition was not provided.

Significant difference between IG and CG shows some decay over time.

Across the 18 studies with behavioral or biologic outcomes, PfP interventions continue to be effective, with all but 3 reducing targeted sexual and/or drug-related risk behaviors; Table 1 provides specifics of relevant studies. Most of the interventions contained elements consistent with those identified earlier as contributing to effective outcomes.11,12 For example, most were developed using one10,37,46–48,50 or more34,38,40–42,45,49 health-behavior theories and were delivered in either an HIV clinic10,35,36,38,39,42,43,45,48,49 or another HIV service venue,40,44 and by professional counselors/therapists40,41,43,44,48,50 or HIV care providers/other medical staff.1,35,39,49 A relatively small number of interventions targeted multiple HIV risk–related behaviors (eg, increasing disclosure, reducing heavy drinking or drug use, or enhancing coping skills36,37,40–45,48,50) and targeted biologic transmission risk factors (eg, increased adherence to ART, reduced viral load37,40,42–45). Compared to previous reviews,1,11,33 we note an increase in the number of PfP interventions tailored to risk dynamics unique to specific subpopulations of PLWHA (eg, decreasing sexual risk in substance-using seropositive MSM).34,40,41,45–47,50,76 Future meta-analysis should evaluate the effectiveness of emerging efforts to use multicomponent and more tailored intervention approaches to reduce overall transmission risk.

NEXT-GENERATION PREVENTION FOR POSITIVES

We believe that a synergistic package of PfP interventions at the intersection of behavior and biology will have optimal impact on limiting HIV transmission and maintaining PLWHA health.1–4,77 In Figure 1, we identify vital components and linkages of a comprehensive behavioral–biomedical conceptualization of next-generation PfP interventions (with an alphanumeric system denoting the various components and paths as well as “movement” within the model—for example, to component C from component B via path i).

All components and linkages need to be co-present and integrated in such an approach. To date, these elements remain separate, unintegrated components of HIV prevention and of treatment science for PLWHA. Finally, we emphasize that the model must be evaluated and supported over the disease course of PLWHA (component A), understanding that what is needed to optimize the effect of each component and path may vary by disease stages78 and subpopulations (eg, PLWHA who are MSM vs IDU; young vs older PLWHA; incarcerated vs unincarcerated PLWHA; PLWHA with different comorbid conditions38,39,43,48,57,77,79–81).

Critical Components of Next-Generation Prevention for Positives

Increased HIV testing (component B) is a critical element in next-generation PfP. This will identify PLWHA who were previously unaware of their serostatus. When individuals learn they are HIV infected, substantial, self-initiated, postdiagnosis reductions in risk behavior often follow.82,83 Testing may also help reduce the number of PLWHA unaware of their status during periods of increased infectiousness (ie, acute, symptomatic, and late stages), which can affect transmission.4,78 Achieving postdiagnosis linkages to HIV care (component C, path i) to reduce biologic risk of transmission (eg, through identification and treatment of STIs and access to ART medications) as well as ensuring linkages to ancillary services (component G, path x) to address behavioral risk–related contextual factors, are essential.

Initiating and maintaining HIV care (component C) aims to facilitate routine primary care visits and continued monitoring of patients’ overall health.84 Routine appointments have been related to lower levels of behavioral79,85,86 and biologic risk (eg, treatment of existing STIs, increased viral suppression, decreased resistance),87–89 whereas prolonged absences from care relate to poorer health outcomes.90,91 Routine care provides ongoing opportunities to reduce biologic transmission through ART initiation (component D, path ii), sustained ART monitoring, and adherence support (component E, path iii). Behavioral risk reduction ideally integrates PfP support (component F, path iv) and referral to ancillary services (component G, path v), addressing contextual risk factors such as social isolation or depression.4,86,92,93

Initiation of ART (component D) rapidly curbs viral replication and reduces the amount of viral load present in plasma or genital tracts, reducing biologic risk of transmission and facilitating overall health.94-97 The relationship between risk behaviors and being on ART or achieving viral suppression is complex, with any increases in risk behavior likely a result of treatment-related beliefs98 and underlying contextual risk factors,2,18,92 not actual receipt of ART or suppressed viral load per se.98 As biologic risk reduction requires sustaining health and high levels of adherence, support in both continuing routine HIV care (component C, path ii) and initial99 and ongoing access to ART adherence support (component E, path vi) are needed.94,96,100

ART adherence behavioral interventions (component E) sustain viral suppression through enhancing adherence behaviors. Optimal adherence decreases biologic risk by controlling both viral replication and potential to develop treatment resistance.94,96,101 Meta-analyses report that adherence interventions significantly improve adherence behavior96,101 and support viral suppression.101 Co-occurrence of both nonadherence and HIV risk behaviors are often identified, likely resulting from common underlying barriers (eg, substance use, social isolation, psychological distress/depression).2,18,92 Integration with ongoing PfP behavioral support (component F, path vii) and referral to ancillary services (component G, path viii) to address root contextual risks4,18,92 can strengthen adherence.

Prevention for positives behavioral interventions (component F) support safer sex and drug use behaviors, and overall health of PLWHA. Meta-analyses of PfP interventions discussed earlier demonstrate their efficacy in reducing behavioral11,12 and potentially biologic risk (ie, STIs11). In the context of existing ART, future PfP interventions need to address ART-related beliefs98 and integrate ART adherence support (E, path vii). Referrals to or incorporation of ancillary services to address root contextual risks (G, path ix) are also critical.1,3,48,80,102

Ancillary treatments and referrals to services (component G) address contextual factors and vulnerabilities that may undermine necessary health behaviors (eg, ability to maintain care, medication adherence, or risk reduction) through referrals to treatment and support services (see a sample list of services in box for component G in Figure 1). These referrals may emanate from HIV testing (component B, path x), HIV care (component C, path v), adherence interventions (component E, path viii), and PfP behavioral interventions (component F, path ix), among other sources. Simultaneously, PLWHA receiving ancillary treatments or services and who are in need of testing, medical care, and behavioral support for existing adherence and risk reduction issues should be identified and connected to other components, as appropriate. For example, HIV testing for high risk individuals (component B, path x), re-engaging PLWHA not in HIV care or who never initiated care postdiagnosis (component C, path v), and providing access to existing adherence (component E, path viii) and risk reduction (component F, path ix) behavioral interventions is critical.

Due to space limitations, our discussion of a comprehensive behavioral–biomedical approach to PfP addresses model components and their links in a somewhat arbitrary, linear fashion. We recognize that the need for any component and relevant linkages could occur along paths not discussed. The next generation of PfP interventions must attend to reducing both behavioral and biologic risk factors across the components in Figure 1 and ensure the linkages among them. Fortunately, some emerging PfP interventions are beginning to incorporate elements of behavioral and biologic risk reduction, but they are not comprehensive and the links are not always fleshed out.37,43,45 Future PfP intervention development needs to ensure the linkages among these components are maintained, enhanced, and evaluated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant R01MH077524-04, Integrating HIV Prevention into Care for People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in South Africa.

Footnotes

Search terms were combined as follows, Group 1 (OR between each term): HIV positive, prevention with positives, prevention for positives, positive prevention, HIV prevention with positives, HIV/AIDS prevention with positives, secondary HIV prevention. Group 2 (OR between each term): prevention, HIV prevention, HIV counseling, transmission, risk behavior, risk reduction, harm reduction. Combine Group 1 AND Group 2 AND intervention.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fisher JD, Smith L. Secondary prevention of HIV infection: the current state of prevention for positives. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4:279–287. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c7ce5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remien RH, Berkman A, Myer L, et al. Integrating HIV care and HIV prevention: legal, policy and programmatic recommendations. AIDS. 2008;22(suppl 2):S57–S65. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327437.13291.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stall R. Efforts to prevent HIV infection that target people living with HIV/AIDS: what works? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S308–S312. doi: 10.1086/522555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Temoshok LR, Wald RL. Integrating multidimensional HIV prevention programs into healthcare settings. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:612–619. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817739b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks G, Burris S, Peterman TA. Reducing sexual transmission of HIV from those who know they are infected: the need for personal and collective responsibility. AIDS. 1999;13:297–306. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902250-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metsch LR, McCoy CB, Lai S, et al. Continuing risk behaviors among HIV-seropositive chronic drug users in Miami, Florida. AIDS Behav. 1998;2:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–149. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalichman SC. Kluwer; New York, NY: 1999. Positive Prevention. Reducing HIV Transmission Among People Living with HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly JA, Kalichman SC. Behavioral research in HIV/AIDS primary and secondary prevention: recent advances and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:626–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, et al. An information–motivation–behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25:462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? a meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, et al. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:642–650. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campsmith ML, Rhodes PH, Hall HI, et al. Undiagnosed HIV prevalence among adults and adolescents in the United States at the end of 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:619–624. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bf1c45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20:1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, et al. Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1021–1036. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town, South Africa. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behavior among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1589–1598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher WA, Kohut T, Fisher JD. AIDS exceptionalism: on the social psychology of HIV prevention research. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2009;3:45–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV: recommendation of the CDC, the Health Resources and Service Administration, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(RR12):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen RS, Holtgrave DR, Valdiserri RO, et al. The serostatus approach to fighting the HIV epidemic: prevention strategies for infected individuals. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1019–1024. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institutes of Health . National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Statement on Interventions to Prevention HIV Risk Behaviors. NIH Office of Medical Applications Research; Bethesda, MD: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moatti JP, Souteyrand Y. HIV/AIDS social and behavioural research: past advances and thoughts about the future. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1519–1532. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00462-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiltz MA, Sandfort TGM. HIV-positive people, risk and sexual behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1571–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, et al. A test of major assumptions about behavior change: a comprehensive look at the effects of passive and active HIV-prevention interventions since the beginning of the epidemic. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher JD, Cornman DH, Osborn CY, et al. Clinician-initiated HIV risk reduction intervention for HIV+ persons; formative research, acceptability, and fidelity of the Options Project. JAIDS. 2004;32:S78–S87. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140605.51640.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalichman SC, Cherry J, Cain D. Nurse-delivered antiretroviral treatment adherence intervention for people with low literacy skills and living with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005;16:3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher WA, Fisher JD. Understanding and promoting AIDS preventive behaviour: a conceptual model and educational tools. Can J Hum Sex. 1992;1:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiene SM, Fisher WA, Shuper PA, et al. An information–motivation–behavioral skills model (IMB) of HIV-preventive behavior among HIV-positive individuals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.. Presented at: XVIII International AIDS Conference; Vienna, Austria. July 18–23, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Shuper PA. The information–motivation–behavioral skills model of HIV preventative behavior. In: DiClemente R, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. 2nd ed. Jossey Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2009. pp. 22–63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilliam PP, Straub DM. Prevention with positives: a review of published research, 1998–2008. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:92–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman CL, Jemmott L, Jemmott JB. Development of an HIV risk reduction intervention for older seropositive African American men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:647–655. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner LI, Marks G, O'Daniels CM, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a clinic-based behavioral intervention: positive steps for patients with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:627–635. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert P, Ciccarone D, Gansky SA, et al. Interactive “Video Doctor” counseling reduces drug and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive patients in diverse outpatient settings. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001988. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Healthy Living Project Team Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: the Healthy Living Project randomized controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:213–221. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c0cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Illa L, Echenique M, Jean GS, et al. Project ROADMAP: Reeducating Older Adults in Maintaining AIDS Prevention: a secondary intervention for older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22:138–147. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Comulada WS, et al. Efficacy of brief interventions in clinical care settings for persons living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:348–356. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c429b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Margolin A, Schuman-Olivier Z, Beitel M, et al. A preliminary study of spiritual self-schema (3-S(+)) therapy for reducing impulsivity in HIV-positive drug users. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63:979–999. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: results from the EDGE study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell CG, Freels S, Creticos CM, et al. Preliminary findings of an intervention integrating modified directly observed therapy and risk reduction counseling. AIDS Care. 2007;19:561–564. doi: 10.1080/09540120601040813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Murphy DA, et al. Improving health outcomes for youth living with the human immunodeficiency virus: a multisite randomized trial of a motivational intervention targeting multiple risk behaviors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:1092–1098. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry NM, Weinstock J, Alessi SM, Lewis MW, Dieckhaus K. Group-based randomized trial of contingencies for health and abstinence in HIV patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:89–97. doi: 10.1037/a0016778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Purcell DW, Latka MH, Metsch LR, et al. Results from a randomized controlled trial of a peer-mentoring intervention to reduce HIV transmission and increase access to care and adherence to HIV medications among HIV-seropositive injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(suppl 2):S35–S47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosser BR, Hatfield LA, Miner MH, et al. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce serodiscordant unsafe sex among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: the Positive Connections randomized controlled trial study. J Behav Med. 2010;33:147–158. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9244-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serovich JM, Reed S, Grafsky EL, et al. An intervention to assist men who have sex with men disclose their serostatus to casual sex partners: results from a pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:207–219. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sikkema KJ, Wilson PA, Hansen NB, et al. Effects of a coping intervention on transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS and a history of childhood sexual abuse. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:506–513. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318160d727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teti M, Bowleg L, Cole R, et al. A mixed methods evaluation of the effect of the Protect and Respect intervention on the condom use and disclosure practices of women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:567–579. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Velasquez MM, von Sternberg K, Johnson DH, et al. Reducing sexual risk behaviors and alcohol use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:657–667. doi: 10.1037/a0015519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowen AM, Horvath K, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:120–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lapinski MK, Randall LM, Peterson M, et al. Prevention options for positives: the effects of a health communication intervention for men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS. Health Commun. 2009;24:562–571. doi: 10.1080/10410230903104947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markham CM, Shegog R, Leonard AD, et al. +CLICK: harnessing Web-based training to reduce secondary transmission among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Care. 2009;21:622–631. doi: 10.1080/09540120802385637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Callahan EJ, Flynn NM, Kuenneth CA, et al. Strategies to reduce HIV risk behavior in HIV primary care clinics: brief provider messages and specialist intervention. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S48–S57. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen HT, Grimley DM, Waithaka Y, Aban IB, et al. A process evaluation of the implementation of a computer-based, health provider-delivered HIV-prevention intervention for HIV-positive men who have sex with men in the primary care setting. AIDS Care. 2008;20:51–60. doi: 10.1080/09540120701449104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collins CB, Jr, Hearn KD, Whittier DN, et al. Implementing packaged HIV-prevention interventions for HIV-positive individuals: considerations for clinic-based and community-based interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(suppl 1):55–63. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Copenhaver M, Chowdhury S, Altice FL. Adaptation of an evidence-based intervention targeting HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community: the process and outcome of formative research for the Positive Living Using Safety (PLUS) intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:277–287. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czuchry M, Timpson S, Williams ML, et al. Improving condom self-efficacy and use among individuals living with HIV: the Positive Choices Mapping Intervention. J Subst Use. 2009;14:230–239. doi: 10.1080/14659890902874212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Estrada BD, Trujillo S, Estrada AL. Supporting healthy alternatives through patient education: a theoretically driven HIV prevention intervention for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S95–S105. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Golin CE, Davis RA, Przybyla SM, et al. SafeTalk, a multicomponent, motivational interviewing-based, safer sex counseling program for people living with HIV/AIDS: a qualitative assessment of patients’ views. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:237–245. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Golin CE, Patel S, Tiller K, et al. Start talking about risks: development of a motivational interviewing-based safer sex program for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S72–S83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grimley DM, Bachmann LH, Jenckes MW, et al. Provider-delivered, theory-based, individualized prevention interventions for HIV-positive adults receiving HIV comprehensive care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S39–S47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holstad MM, DiIorio C, Magowe MK. Motivating HIV-positive women to adhere to antiretroviral therapy and risk reduction behavior: the KHARMA Project. Online J Issues Nurs. 2006;11:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White D, et al. Altering key characteristics of a disseminated effective behavioral intervention for HIV positive adults: the “healthy relationships” experience. J Prim Prev. 2007;28:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Knauz RO, Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, et al. Developing an HIV-prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men in HIV care: Project Enhance. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S117–S126. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lightfoot M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tevendale H. An HIV-preventive intervention for youth living with HIV. Behav Modif. 2007;31:345–363. doi: 10.1177/0145445506293787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mitchell CG, Perloff J, McVicker J, et al. Integrating prevention in residential and community care settings: a multidimensional program evaluation. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(1 suppl A):89–101. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.2.89.58696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Naar-King S, Wright K, Parsons JT, et al. Healthy choices: motivational enhancement therapy for health risk behaviors in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18:1–11. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naar-King S, Lam P, Wang B, et al. Brief report: maintenance of effects of motivational enhancement therapy to improve risk behaviors and HIV-related health in a randomized controlled trial of youth living with HIV. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:441–445. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nollen C, Drainoni ML, Sharp V. Designing and delivering a prevention project within an HIV treatment setting: lessons learned from a specialist model. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S84–S94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raja S, McKirnan D, Glick N. The Treatment Advocacy Program–Sinai: a peer-based HIV prevention intervention for working with African American HIV-infected persons. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S127–S137. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Raja S, Teti M, Knauz RO, et al. Implementing peer-based intervention in clinic-based settings: lessons from a multi-site HIV prevention with positives initiative. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2008;7:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rutledge SE. Single-session motivational enhancement counseling to support change toward reduction of HIV transmission by HIV positive persons. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:313–319. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teti M, Rubinstein S, Lloyd L, et al. The Protect and Respect Program: a sexual risk reduction intervention for women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(suppl 1):S106–S116. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9275-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams JK, Ramamurthi HC, Manago C, et al. Learning from successful interventions: a culturally congruent HIV risk-reduction intervention for African American men who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1008–1012. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, et al. Outcomes from a group intervention for coping with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse: reductions in traumatic stress. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hart GJ, Elford J. Sexual risk behaviour of men who have sex with men: emerging patterns and new challenges. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:39–44. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334feb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. Changes in transmission risk behaviors across stages of HIV disease among people living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coleman SM, Rajabiun S, Cabral HJ. Sexual risk behavior and behavior change among persons newly diagnosed with HIV: the impact of targeted outreach interventions among hard-to-reach populations. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:639–645. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grossman CI, Gordon CM. Mental health considerations in secondary HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Schiltz MA, et al. Vulnerability, unsafe sex and non-adherence to HAART: evidence from a large sample of French HIV/AIDS outpatients. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2420–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, et al. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, et al. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985–1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horstmann E, Brown J, Islam F, et al. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: where are we? where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gardner LI, Marks G, Metsch LR, et al. Psychological and behavioral correlates of entering care for HIV infection: the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS). AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:418–425. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Latkin CA, Buchanan AS, Metsch LR, et al. Predictors of sharing injection equipment by HIV-seropositive injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:447–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31818a6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Erbelding EJ, Stanton D, Quinn TC, et al. Behavioral and biologic evidence of persistent high-risk behavior in an HIV primary care population. AIDS. 2000;14:297–301. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mellins CA, Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, et al. Sexual and drug use behavior in perinatally HIV-infected youth: mental health and family influences. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:810–819. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a81346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takizawa C, Cheng D, Samet J, et al. Primary medical care and reductions in HIV risk behaviors in adults with addictions. J Addict Dis. 2007;26:17–25. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parks DA, Jennings HC, Taylor CW, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily tenofovir, emtricitabine, ritonavir and fosamprenavir in HIV-infected subjects. AIDS. 2007;21:1373–1375. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328133f068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berg CJ, Michelson SE, Safren SA. Behavioral aspects of HIV care: adherence, depression, substance use, and HIV-transmission behaviors. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Myers JJ, Shade SB, Rose CD, et al. Interventions delivered in clinical settings are effective in reducing risk of HIV transmission among people living with HIV: results from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)'s Special Projects of National Significance initiative. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9679-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bangsberg DR. Preventing HIV antiretroviral resistance through better monitoring of treatment adherence. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 3):S272–S278. doi: 10.1086/533415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bangsberg DR, Acosta EP, Gupta R, et al. Adherence-resistance relationships for protease and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors explained by virological fitness. AIDS. 2006;20:223–231. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000199825.34241.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: a research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lalani T, Hicks C. Does antiretroviral therapy prevent HIV transmission to sexual partners? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0012-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292:224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mannheimer SB, Morse E, Matts JP, et al. Sustained benefit from a long-term antiretroviral adherence intervention. Results of a large randomized clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(suppl 1):S41–S47. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000245887.58886.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Simoni JM, Amico KR, Smith L, et al. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: translating research findings to the real world clinic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:44–51. doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Simoni JM, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, et al. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Vol. 43. suppl 1: 2006. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. pp. S23–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Remien RH, Mellins CA. Long-term psychosocial challenges for people living with HIV: let's not forget the individual in our global response to the pandemic. AIDS. 2007;21(suppl 5):S55–S63. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000298104.02356.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.