SUMMARY

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma is the most common orbital tumour. We conducted a retrospective analysis to examine: a) the impact of initial presentation and staging on outcome; b) response to various treatment modalities and the effect of the latter on recurrence.

90 patients with primary ocular adnexal marginal zone lymphoma (POAML) diagnosed at our institution between 1984 and 2009 were studied.

POAML was associated with monoclonal gammopathy (13%) at presentation. Most POAML patients (86%) presented with Ann-Arbor stage I disease. Radiotherapy led to excellent local control, but relapses occurred in 18% of Ann-Arbor stage I patients during a median follow-up of 5 years. Local relapses, including secondary central nervous system (CNS) involvement, were observed in patients receiving radiation doses < 30.6 Gy. No differences in relapse rate and survival were observed between patients who did or did not undergo staging bone marrow biopsy. Ann-Arbor stage II-IV disease and high lactate dehydrogenase levels were associated with shorter freedom from progression. In conclusion, POAML is an indolent lymphoma with continuous risk for relapse. Radiation doses of at least 30.6 Gy should be given in Ann-Arbor stage I disease, since lower doses may be more frequently associated with relapses, including CNS relapses.

Keywords: bone marrow biopsy, chemotherapy, monoclonal gammopathy, primary ocular adnexal marginal zone lymphoma, radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Ocular adnexal lymphomas (OAL) are a heterogeneous group of malignancies, accounting for up to 55% of all orbital tumours (Margo and Mulla 1998, Woo, et al 2006, Wotherspoon, et al 1993), about 2% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) and 8% of extranodal lymphomas (Freeman, et al 1972). Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (EMZL) of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type is the most common histological subtype, accounting for 35% to 90% of primary OAL cases (Cho, et al 2003, Ferry, et al 2007, McKelvie, et al 2001, White, et al 1995).

The majority of primary ocular adnexal marginal zone lymphomas (POAML) present with localized disease (Rosado, et al 2006, Stefanovic and Lossos 2009). The orbit is the most frequent site of origin, accounting for approximately 40% of cases (Moslehi, et al 2006). Primary conjunctival manifestations are seen in approximately one third of patients, and bilateral involvement, affecting 10–15% of all cases, is most frequently observed at this site (Ferreri, et al 2008).

Although major advances in elucidating aetiology, clinical manifestation, natural history and treatment of POAML have been achieved in recent years (Stefanovic and Lossos 2009), many important aspects of this lymphoma have still not been sufficiently addressed. While several studies have reported an association with Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci) in certain geographic regions (Stefanovic and Lossos 2009), this association is not universal and other predisposing conditions may exist. There is no consensus regarding the initial management of POAML. While radiotherapy (RT) is generally considered the most effective treatment modality for localized disease, achieving durable clinical remissions in 85–100% of patients (Le, et al 2002, Tsang, et al 2003), the optimal dose of RT is still debatable. Furthermore, despite offering excellent local control, RT may be inadequate in preventing systemic relapse, occurring in 5%–32% of patients (Cahill, et al 1999, Charlotte, et al 2006, Cho, et al 2003, Coupland, et al 2005, Lee, et al 2005, McKelvie, et al 2001, White, et al 1995). Few retrospective case series have reported on the use of chemotherapy (CT), either alone or in combination with other treatment modalities in patients with POAML (Ben Simon, et al 2006, Charlotte, et al 2006, Lee, et al 2005, Song, et al 2008, Sullivan and Valenzuela 2006) and few small prospective studies have assessed the efficacy of antibiotic therapy (Ferreri et al 2005), and Y-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan(Esmaeli, et al 2009); however, overall the data is limited due to small patient numbers and lack of large prospective studies. The impact of staging bone marrow (BM) biopsy on initial treatment decisions and outcome of patients with POAML is still controversial. Likewise, it is still unclear whether primary disease site or other clinical features at initial presentation affect clinical outcome. Although some studies have identified nodal involvement and age >60 years as poor prognostic factors (Charlotte, et al 2006, Meunier, et al 2006, Tanimoto, et al 2007), other studies did not confirm these observations (Charlotte, et al 2006, Coupland, et al 2005, Tanimoto, et al 2006, Woo, et al 2006).

To shed some light on these important issues, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 90 patients with POAML diagnosed and treated at our institution between 1984 and 2009. The goal of this analysis was to a) identify predisposing conditions in our patients that do not harbour C. psittaci (Matthews et al 2008, Rosado, et al 2006, Stefanovic and Lossos 2009); b) analyse the impact of initial presentation - with particular attention to different disease locations in the ocular adnexa - and initial staging on outcome; and c) to examine the effect of different doses of initial RT on local response and recurrence patterns.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

After approval by our institutional review board, review of the institutional tumour registry and the pathology database identified 90 patients with POAML diagnosed and/or treated between January 1984 and December 2009 at the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. A total of 55 patients seen between 1991 and 2004 were reported previously (Rosado, et al 2006), but their clinical follow-up was updated for this study. All pathology specimens were reviewed by a haematopathologist and classified according to the World Health Organization classification (Swerdlow et al 2008) based on the characteristic morphological and immunophenotypic features of MALT lymphoma and evidence of B-cell monoclonality by gene rearrangement studies. A total of 64 of the 90 specimens were evaluated for presence of C. psittaci using methodology reported previously (Rosado, et al 2006) and all were negative. The following information was extracted from the medical records and data base: basic patient demographics, relevant medical history, presenting clinical symptoms, anatomic location of the lesion(s), Karnofsky performance status (KPS), laboratory data, radiological imaging studies, disease stage, details on treatment, response to therapy, timing and location of recurrence, management of recurrent or progressive disease, freedom from progression (FFP), overall survival (OS), second-line therapy and disease status at last follow-up. Patients presenting with bilateral ocular adnexal involvement were designated as Ann-Arbor stage IE disease, according to the current Ann Arbor staging classification (Carbone, et al 1971). Primary disease sites were distinguished as orbital, conjunctival, and lacrimal apparatus, based on ophthalmological examination and radiological studies. Ann-Arbor stage IE tumours were further categorized according to the proposed tumour, node, metastases (TNM)-based American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) International Union Against Cancer ocular lymphoma staging system (Coupland, et al 2009). Staging evaluation was not standardized, but included ophthalmological and complete physical examination; haematological and chemical survey with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), computerized tomography of the orbit, chest, abdomen, and pelvis; sonography of salivary glands, and gastroscopy. As the patients included in this study were seen over a very long time interval, the decision to perform staging bone marrow biopsy and serum protein electrophoresis was at the discretion of the treating oncologist; they were routinely done in patients seen by two of the authors. Similarly, the doses of RT given to the patients were at the discretion of treating radiation oncologist until 2003, when the 30.6 Gy dose became standard at our institution.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between patient subgroups using the student’s t-test and chi-square test. OS was calculated from the time of initial diagnosis until death from any cause or last follow-up. FFP was calculated from the start of treatment until disease progression, transformation, relapse, or last follow-up. For patients who remained progression-free but died of POAML-unrelated causes, the follow-up was censored at the time of death. Patients with less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded from survival analyses unless they relapsed during this time period. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed and compared between subgroups using the log rank test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Standard error was used as the measure of variance. Predictive Analytic Software (PASW), version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics, disease sites and presenting symptoms

Between 1984 and 2009, 90 patients with POAML were diagnosed and/or received treatment at our institution. Demographic and clinical characteristics of POAML patients are summarized in Table I. Five patients had antecedent thyroid disease (Graves disease in 2 and Hashimoto thyroiditis in 3). None of these patients had thyroid orbitopathy. An additional four patients had a previous diagnosis of non-thyroid autoimmune disease, including rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriasis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Anatomically the tumours were distributed as follows: orbit in 41 patients (46%), conjunctiva in 32 patients (36%), and lacrimal apparatus in 17 patients (19%). One patient had synchronous involvement of the orbit and the lacrimal apparatus (included in the lacrimal group in analyses). Another patient with orbital EMZL had synchronous eyelid involvement (stage T3 based on the AJCC staging classification) but because it was a single case, it was included in the orbit group. POAML was more common in females (2:1). However this predominance was due to higher frequency of conjunctival POAML in females, while orbital and lacrimal POAML did not demonstrate gender preference. Patients with lacrimal POAML presented at an earlier age compared to those with orbital and conjunctival lymphomas.

Table I.

Demographic and selected clinical characteristics of patients with POAML

| Characteristic | POAML, n=90 (%) |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 31 (34) |

| Median age (range), years | 63 (24–92) |

| Age > 65 years | 43 (48) |

| LDH > normal /tested | 5/66 (8) |

| Anatomical location | |

| Conjunctivae | 32 (36) |

| Orbit | 41 (46) |

| Lacrimal apparatus | 17 (19) |

| Median duration of symptoms (months, range) | 6 (1–48) |

| Ann-Arbor Stage | |

| IE | 77 (86) |

| II | 3 (3) |

| III | 2 (2) |

| IV | 8 (9) |

| AJCC Stage | |

| T1 | 30 (39) |

| T2 | 46 (60) |

| T3 | 1 (1) |

| T4 | 0 |

| Nodal involvement | 6 (6) |

| BM involvement | 5/54 (9) |

| Other involved sites | |

| Spleen | 2 |

| Cutaneous | 1 |

| Oropharynx | 1 |

| Pulmonary | 1 |

| β2-microglobulin > 3.0 / tested | 5/19 (26) |

| M-protein (positive/tested) | 5/38 (13) |

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase; BM: Bone marrow; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Presenting symptoms differed according to primary tumour sites. Visible lesions were more common in patients with conjunctival lymphoma, whereas periorbital oedema was more common in patients with orbital and lacrimal EMZL. None of the patients had extraocular complaints or B-symptoms. Blood for monoclonal gammopathy (MG) was tested in 38 patients. MG was found in 5(13%) tested patients (aged 47, 49, 51, 70 and 90 years).

Stage and extent of lymphoma at presentation

On presentation, 77 (86%) patients had Ann-Arbor stage I, 3 patients Ann-Arbor stage II, 2 patients Ann-Arbor stage III, and 8 patients Ann-Arbor stage IV disease. Of 77 patients with Ann-Arbor stage I disease; 30 (39%) had a tumour classified as T1N0M0, 46 patients (51%) were T2N0M0, and 1 patient was T3N0M0 according to the AJCC staging system. Nine patients had bilateral ocular adnexal involvement, 8 of whom had Ann-Arbor stage I disease. BM involvement by lymphoma (stage M1b based on the AJCC staging system) was found in 5 (9%) of 54 patients who underwent BM biopsy. Had a BM biopsy not been performed, 3 of these 5 patients would have been staged as Ann-Arbor stage I/II disease. Among 36 patients who did not undergo BM biopsy at presentation, 34 had Ann-Arbor stage I disease, one was Ann-Arbor stage III, and one was Ann-Arbor stage IV. Other extraocular sites involved by lymphoma at presentation included spleen in 2 patients and skin, oropharynx, and lung in 1 patient each.

Treatment, response and follow-up

Data on first-line treatment and response were available for 86 patients (Ann-Arbor stage I-73 patients; Ann-Arbor stage II-3 patients; Ann-Arbor stage III-2 patients and Ann-Arbor stage IV-8 patients). Treatment modalities, response rates, and relapses were stratified according to disease stage in Table II. Overall, 77 (90%) of 86 patients achieved a complete response (CR) after first-line treatment; while 7 patients achieved a partial remission (PR), one patient had stable disease (SD), and one patient had progressive disease (PD). Two patients with Ann-Arbor stage IV disease due to microscopic BM involvement received orbital radiation leading to complete local response, and thus were classified as PR.

Table II.

Complete remission (CR) rates and relapse locations after first-line therapy stratified according to disease stage at presentation

| Ann-Arbor Stage | AJCC Stage | First-line therapy | N | CR | Relapse/Progression type 1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Extraorbital | Combined | |||||

| I | RT | 70 | 68 | 4 | 8 | 2 | |

| Rituximab | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Surgical resection | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| T1 | RT | 27 | 27 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Rituximab | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| T2 | RT | 42 | 41 | 1 | 4 | 2 | |

| Rituximab | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Surgical resection | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| T3 | RT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| II | RT | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rituximab | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| III | Ibritumomab tiuxetan | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RT followed by Chl/P | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| IV | RT | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| CT±Rituximab 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Ibritumomab tiuxetan | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| RT followed by R-CVP | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer, .RT: Radiation therapy, Chl/P: Chlorambucil and prednisone, CT: chemotherapy, R-CVP: Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone

Number of relapse/progression in all patients regardless of their response to first-line therapy

Includes Chl/P with/without rituximab (3) and R-CVP (1)

Seventy-three of 86 patients with available response data (85%) received RT alone. Of those, 70 (96%) had Ann-Arbor stage I, 1 had Ann-Arbor stage II, and 2 had Ann-Arbor stage IV disease (BM involvement only). In the patient with Ann-Arbor stage II disease, RT was given to all involved sites. In 70 patients with Ann-Arbor stage I POAML treated with RT monotherapy, median radiation dose was 30.6 Gy (range 23.5–45.0 Gy). All 52 patients with Ann-Arbor stage I disease who received ≥30.6 Gy achieved a CR. In contrast, 16 of the 18 (89%) Ann-Arbor stage I patients who received <30.6 Gy (mean: 28.7 Gy) achieved a CR, while 2 patients achieved a PR (p=0.014). Two, three and one (total 6) of 18 patients who received <30.6 Gy (33%) developed localized, systemic and combined disease progression/relapse, respectively, while only two, five and one (total 8) of 52 patients (15%) who received ≥30.6 Gy experienced localized, systemic and combined disease relapse, respectively.

None of the patients who received RT of ≥30.6 Gy experienced central nervous system (CNS) relapse. In contrast, three patients with Ann-Arbor stage I disease who were initially treated with RT of <30.6 Gy developed recurrent disease in the CNS. The first patient presented with blurry vision 4 years after the completion of RT and was found to have a large orbital mass extending into the cavernous sinus with optic nerve and dural involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis confirmed leptomeningeal involvement. The patient achieved a CR with methotrexate-containing CT. The second patient presented with bilateral intraocular lymphoma with retinal cellular infiltrates 5 years after initial treatment and achieved a CR after methotrexate-containing CT and RT. The third patient developed back pain and lower extremity weakness 5 years after initial presentation and magnetic resonance imaging of the spine demonstrated an epidural mass causing spinal cord compression. The patient underwent laminectomy followed by RT, achieving a CR.

Of 80 POAML patients who received orbital RT at any point in the treatment of their disease, 12 (15%) developed cataract, 4 (5%) developed dry eye, 2 (3%) had retinal complications including macular degeneration and retinal detachment, 2 (3%) developed ptosis, 1 (1%) developed chalazion, and 1 (1%) developed glaucoma. There was no difference in side effects between patients who received <30.6 Gy and ≥30.6 Gy.

One patient with Ann-Arbor stage I lacrimal lymphoma was managed with surgical resection alone and has remained in CR without further therapy. None of the patients with Ann-Arbor stage I/II disease were treated with CT. Of four patients with Ann-Arbor stage I/II disease who received single-agent rituximab, 2 achieved a sustained CR, while 2 patients had SD. Four patients with Ann-Arbor stage IV disease were treated with CT ± rituximab, achieving CR (3) and PR (1). Two of the patients achieving CR eventually relapsed and one has been in continuous CR for 14 months. Two patients with Ann-Arbor stage III/IV disease received radioimmunotherapy with Y-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan, achieving CR (1) and mixed response (1) with SD in the orbit and disappearance of all extraorbital disease.

Survival, outcome and prognostic factors

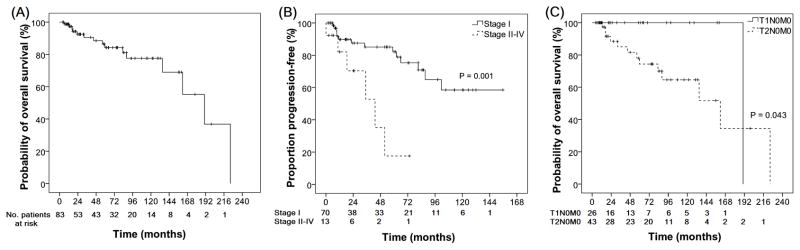

Eighty-three patients were eligible for survival analysis. During a median follow-up of 57.5 months (range: 4.3 – 224.4 months), 15 patients had died - 2 of lymphoma and 13 due to unrelated/unknown causes. One patient progressed with transformation to diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Median OS for all patients was 190.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 135.6 – 245.0; Fig 1A). Of 74 patients who achieved a CR after the first-line treatment, 5 (7%), 7 (9%), and 2 (3%) eventually developed local, extraorbital or combined relapse, respectively. Kaplan-Meier estimates for the FFP for all 83 patients at 1, 5, and 10 years after completion of the first-line treatment were 88.6% (95% CI: 81.4% – 96.4%), 73.6% (95% CI: 62.6% – 86.6%), and 52.6% (95% CI: 36.9% – 75.0%), respectively. The median FFP was not attained. The 2 patients that received local radiation for Ann-Arbor stage IV disease (BM involvement only) demonstrated systemic disease progression with multiple lymphadenopathies within 5 years of radiation. Even in patients with initial Ann-Arbor stage IE disease, relapses occurred continuously with estimates of cumulative relapse/progression of 10.2% at 1 year, 17.8% at 5 years, and 41.5% at 10 years.

Figure 1.

Survival of patients with POAML. (A) Overall survival of all the patients; (B) Freedom from progression in patients with Ann-Arbor stage I versus II-IV disease; (C) Overall survival of patient with conjunctival (T1N0M0) and orbital (T2N0M0) Ann Arbor stage I patients.

Of 20 patients with POAML who progressed/relapsed during follow-up, 4 were lost to follow-up before second-line therapy. Three patients with local relapse were treated with RT and achieved a second CR. All 9 patients with extraocular relapse achieved a second CR after second-line treatment with either RT (n=3), CT (n=5), or combined modality therapy (n=1). CT that was used at the time of relapse included CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone), chlorambucil and prednisone, and DeAngelis protocol (DeAngelis et al 2002) + RT. Among 4 patients with combined local and extraocular relapses, 2 achieved a CR after RT and/or surgical resection; while the other 2 achieved a PR after CT.

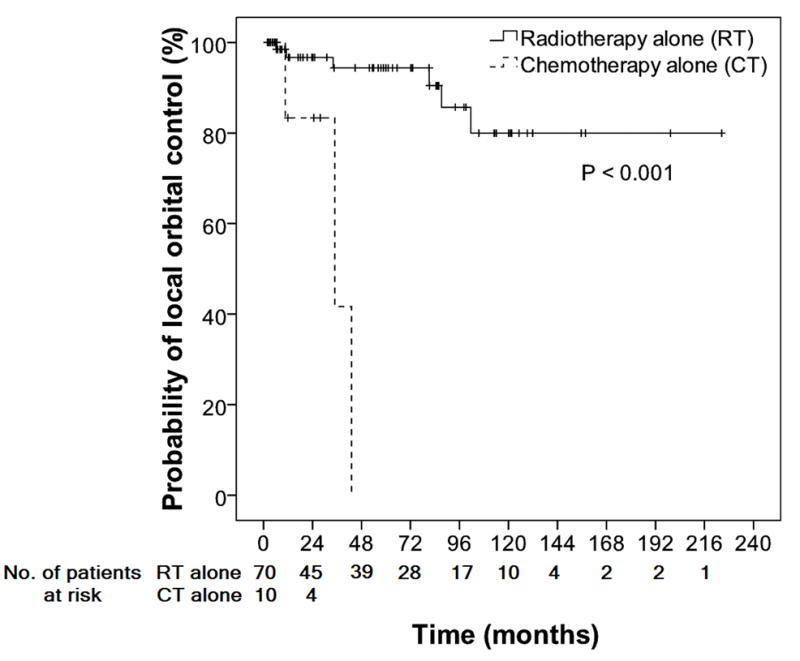

Prognostic factors for OS and FFP were identified and are shown in Table III and Fig 1B-C. Ann-Arbor stage II-IV disease, and high LDH levels were factors associated with shorter FFP, whereas older age and T2N0MO tumour according to the AJCC staging were associated with shorter OS compared to T1N0M0 tumours. There was no difference in FFP between patients with T1N0M0 and T2N0M0 disease. As first-line treatment, CT/immunotherapy was associated with shorter time-to-local relapse compared to RT (Fig 2). POAML location and performance/non-performance of staging BM biopsy, irrespective of the location of POAML, were not associated with FFP or OS.

Table III.

Prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) and freedom from progression/relapse (FFP) in patients with POAML

| Factors | OS (months) | FFP (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | P | Median (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age | ≤65 years (42) | NR | 0.008 | NR | NS |

| >65 years (41) | 161.7 (79.8–243.5) | NR | |||

| Stage | I (70) | 161.7 (107.8–215.5) | NS | NR | 0.001 |

| II–IV (13) | NR | 43.2 (17.0–69.4) | |||

| LDH | ≤ULN (58) | 190.3 | NS | NR | <0.001 |

| >ULN (4) | NR | 22.4 (3.5–41.3) | |||

| AJCC Stage among Ann Arbor stage I patients | T1N0M0 (26) | 190.3 | 0.043 | 101.5 | NS |

| T2N0M0 (43) | 161.7 (81.1–242.2) | NR | |||

| BM biopsy performed | No (35) | 161.7 (114.5–208.8) | NS | NR | NS |

| Yes (48) | NR | NR | |||

CI: Confidence interval, NR: not reached, NS: non-significant, ULN: upper limit of normal, LDH: serum lactate dehydrogenase level, BM: bone marrow, RT: radiotherapy, CT/IT: Chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy (rituximab/ibritumomab tiuxetan)

Figure 2.

Local control curves in patients with extranodal marginal zone lymphomas involving ocular adnexa who were treated with RT alone and CT alone

DISCUSSION

POAML represents 10–55% of all orbital tumours (Margo and Mulla 1998, Woo, et al 2006, Wotherspoon, et al 1993) and its incidence has risen steadily between 1975 and 2001, with an annual increase of 6.3% (Moslehi, et al 2006). The present study summarized our single-institution experience in a large cohort of POAML patients. Our study not only confirmed some of the previously reported observations, but also provided new information on clinical associations, laboratory findings, prognostic factors, therapy and outcome of these patients.

Similar to previous reports, the median age of our patients was 62 years (Cahill, et al 1999, Cho, et al 2003) with female predominance (male/female=1:2) (Auw-Haedrich, et al 2001, Fung, et al 2003, Jenkins, et al 2003, McKelvie, et al 2001). Notably, the latter was mainly due to the higher frequency of conjunctival POAML in females, without gender differences in other primary orbital adnexal locations. The most frequently involved anatomical sites were orbital connective tissue and conjunctiva, as previously reported (McKelvie, et al 2001, Tanimoto, et al 2007). In our patients, the observed frequency of antecedent autoimmune diseases (4%) and thyroid disorders (5.5%) was not different from the general population (Jacobson, et al 1997, Rose & Mackay 1998), thus not confirming previous observations associating POAML with these diseases (Jenkins, et al 2003, Kubota and Moritani 2007).

MG was detected in 5 (13%) of tested POAML patients at the time of diagnosis, including relatively young patients (ages 47–51 years). The presence of a small monoclonal (M)-band (usually less than 30 g/l) has been documented in up to 50% of patients with splenic marginal zone B cell lymphoma (MZBCL) (Catovsky and Matutes 1999), but MG has only rarely been described in patients with EMZL (Economopoulos, et al 2003). Previous reports have suggested a possible association between MG and more advanced splenic MZBCL, bone marrow involvement, and a tendency for large-cell transformation (Asatiani, et al 2004, Iwase, et al 2000, Nakata, et al 1997, Valdez, et al 2001). In our cohort, MG was not associated with advanced Ann-Arbor stage disease, histological transformation or worse prognosis, but the number of patients was small. The small number of patients with MG also prohibited correlation between persistence of MG following initial therapy and risk of subsequent relapse. While polyclonal gammopathy associated with autoimmune diseases has been observed in 9% of patients with POAML and was correlated with disseminated disease (Kubota, et al 2008), to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first description of MG in these patients. We assume that MG is under-diagnosed in patients with POAML, as laboratory testing for its presence is rarely done.

Most of our patients presented with Ann-Arbor stage I disease, as reported previously (Charlotte, et al 2006, Fung, et al 2003, Tanimoto, et al 2007). While it is generally accepted that initial staging of patients with POAML should include ophthalmological evaluation, complete physical examination and computed tomography of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, the value of BM biopsy and aspiration is controversial. Although approximately one third of patients with non-gastrointestinal MALT lymphomas present with disseminated disease at the time of diagnosis (Sretenovic, et al 2009, Thieblemont, et al 2000, Zinzani, et al 1999), Ann-Arbor stage IV disease is observed in 15% to 25% of patients with POAML and BM involvement is reported in 5% to 10% of the patients (Decaudin, et al 2006, Ferry, et al 1996, Fung, et al 2003). A BM biopsy was performed in 54 (60%) of our patients and BM involvement by lymphoma was detected in 5 (9%) patients. There were no differences in relapse rate (RR), OS and FFP between patients who did and those who did not have a staging BM biopsy. Similarly, FFP and OS were not affected by BM involvement in patients with MALT lymphoma of other primary sites (Thieblemont, et al 2000). Although our findings may suggest that the therapeutic approach in patients with POAML should be determined irrespective of BM biopsy results and that the latter may not be a necessary component of staging, the low frequency of BM involvement may argue for larger studies to unequivocally make such a recommendation.

Excellent local control (97%) was achieved in patients with Ann-Arbor stage I POAML using RT; however the local relapse rate was higher in patients who received <30.6 Gy, corroborating the observations of other investigators (Fung, et al 2003, Le, et al 2002, Uno, et al 2003). RT also accounted for higher rates of local disease control compared to CT. No significant differences in OS, FFP and ophthalmological toxicities were observed between patients receiving doses <30.6 Gy compared to higher doses. Higher rates of ophthalmological toxicity with vision loss have been reported after doses of ≥34 Gy (Le, et al 2002). We also observed late CNS relapses in 3 patients (3%) with initial Ann-Arbor stage I POAML, all treated with RT of <30.6 Gy resulting in suboptimal local control. Despite the proximity of the ocular region to the CNS, intracranial involvement by POAML has been rarely observed (Coupland, et al 2005, Ferry, et al 2007, Tanimoto, et al 2007). In one large series (Restrepo, et al 1998), none of 71 patients with POAML had CNS relapse over 2 years of follow-up. In another series, only 3% of POAML showed direct extra-orbital invasion while a relatively high tendency (13%) was noted in deep orbital lymphomas (Nam, et al 2009). Longer follow-up in our patient cohort compared to the relatively short follow-up in the study by Restrepo et al ( 1998) may account for the observed differences. In conclusion, CNS involvement by POAML is rare but may occur, possibly as a result of suboptimal local control after RT doses of <30.6 Gy. These findings advocate the use of RT doses of ≥30.6 Gy to achieve durable local disease control. However, despite excellent initial clinical response with RT, local and systemic relapses occurred in an estimated 20% of Ann-Arbor stage I/II patients during a median follow-up of 5 years. Some relapses occurred after prolonged follow-up and no plateau was observed on FFP curves, suggesting that patients with Ann-Arbor stage I POAML face a continuous risk of distant relapse which increases from an estimated cumulative progression rate of 17.8% at 5 years to 41.5% at 10 years. Similar local and systemic relapse rate after first-line RT have been previously observed (Ejima, et al 2006, Fung, et al 2003, Hasegawa, et al 2003, Lee, et al 2005, Suh, et al 2006, Tanimoto, et al 2007, Tsang, et al 2003, Uno, et al 2003). This can be explained by the presence of microscopic disease outside the treated area. Therefore, patients may achieve excellent local control, but later develop distant recurrence. We are currently conducting a prospective trial to assess this hypothesis using radioimmunotherapy. Specific genetic aberrations (e.g. trisomy 3, trisomy 18, t(14;18) may be predictive of multifocal-disseminated disease and propensity for recurrence (Raderer, et al 2006), however these studies were not performed in our patients.

Similar to previous studies (Coupland, et al 1998, Ellis, et al 1985, Knowles, et al 1990, Medeiros, et al 1989, White, et al 1995), there was no difference in the relapse rates between unilateral or bilateral POAML and most of the systemic relapses were extranodal. The highrate of systemic relapse for Ann-Arbor stage I POAML contrasts with the results reported for localized MALT lymphoma of the stomach, which demonstrate a very low risk of distant recurrence, but is concordant with the high risk of systemic relapse observed in other non-gastric EMZL (Tsang and Gospodarowicz 2007).

In many case series, non-conjunctival primary site, advanced Ann-Arbor disease stage, nodal involvement, age >60 years, presence of B symptoms, and elevated serum LDH levels were identified as negative prognostic factors in patients with POAML (Auw-Haedrich, et al 2001, Cho, et al 2003, Fung, et al 2003, Jenkins, et al 2000, McKelvie, et al 2001, Meunier, et al 2004, Rosado, et al 2006). In our cohort, patients with advanced Ann-Arbor stage and high LDH at presentation (III/IV) had shorter FFP, but OS was not significantly different, suggesting effective control with second-line therapies. Age >65 years and non-conjunctival primary site (T2N0M0 compared to T1N0M0 disease) were the only prognostic factors predicting shorter OS. Overall, POAML shows indolent behavior and clinical outcome is excellent, despite frequent and continuous relapses.

In conclusion, our study confirms the relatively indolent nature of POAML, characterized by long survival with persistent risk for relapses. Radiation at doses ≥30.6 Gy should be given in Ann-Arbor stage I disease, since lower doses are associated with more frequent relapses, including CNS relapses, which are reported for the first time in POAML. Association between POAML and MG is also reported for the first time and additional studies are needed to confirm this observation. Our findings also suggest that BM involvement does not affect clinical outcome of POAML patients and therefore, BM biopsy may not be required as part of initial staging.

Acknowledgments

Funding

ISL is supported by the United States Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R01-CA109335, R01-CA122105]; and the Dwoskin Family Foundation.

References

- Asatiani E, Cohen P, Ozdemirli M, Kessler CM, Mavromatis B, Cheson BD. Monoclonal gammopathy in extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (ENMZL) correlates with advanced disease and bone marrow involvement. American Journal of Hematology. 2004;77:144–146. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auw-Haedrich C, Coupland SE, Kapp A, Schmitt-Graff A, Buchen R, Witschel H. Long term outcome of ocular adnexal lymphoma subtyped according to the REAL classification. Revised European and American Lymphoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2001;85:63–69. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Simon GJ, Cheung N, McKelvie P, Fox R, McNab AA. Oral chlorambucil for extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue of the orbit. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1209–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill M, Barnes C, Moriarty P, Daly P, Kennedy S. Ocular adnexal lymphoma-comparison of MALT lymphoma with other histological types. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 1999;83:742–747. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, Smithers DW, Tubiana M. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin’s Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Research. 1971;31:1860–1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catovsky D, Matutes E. Splenic lymphoma with circulating villous lymphocytes/splenic marginal-zone lymphoma. Seminars in Hematology. 1999;36:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlotte F, Doghmi K, Cassoux N, Ye H, Du MQ, Kujas M, Lesot A, Mansour G, Lehoang P, Vignot N, Capron F, Leblond V. Ocular adnexal marginal zone B cell lymphoma: a clinical and pathologic study of 23 cases. Virchows Archiv. 2006;448:506–516. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-0122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho EY, Han JJ, Ree HJ, Ko YH, Kang YK, Ahn HS, Ahn SD, Park CJ, Huh J. Clinicopathologic analysis of ocular adnexal lymphomas: extranodal marginal zone b-cell lymphoma constitutes the vast majority of ocular lymphomas among Koreans and affects younger patients. American Journal of Hematology. 2003;73:87–96. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland SE, Krause L, Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Foss HD, Hummel M, Bornfeld N, Lee WR, Stein H. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the ocular adnexa. Analysis of 112 cases. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1430–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)98024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland SE, Hellmich M, Auw-Haedrich C, Lee WR, Anagnostopoulos I, Stein H. Plasmacellular differentiation in extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexa: an analysis of the neoplastic plasma cell phenotype and its prognostic significance in 136 cases. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005;89:352–359. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.047092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland SE, White VA, Rootman J, Damato B, Finger PT. A TNM-based clinical staging system of ocular adnexal lymphomas. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 2009;133:1262–1267. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis LM, Seiferheld W, Schold SC, Fisher B, Schultz CJ Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93-10. Combination chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary central nervous system lymphoma: Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 93-10. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4643–4648. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaudin D, de Cremoux P, Vincent-Salomon A, Dendale R, Rouic LL. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a review of clinicopathologic features and treatment options. Blood. 2006;108:1451–1460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulos T, Papageorgiou S, Pappa V, Papageorgiou E, Valsami S, Kalantzis D, Xiros N, Dervenoulas J, Raptis S. Monoclonal gammopathies in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Leukemia Research. 2003;27:505–508. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejima Y, Sasaki R, Okamoto Y, Maruta T, Azumi A, Hayashi Y, Demizu Y, Ota Y, Soejima T, Sugimura K. Ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiotherapy. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2006;78:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JH, Banks PM, Campbell RJ, Liesegang TJ. Lymphoid tumors of the ocular adnexa. Clinical correlation with the working formulation classification and immunoperoxidase staining of paraffin sections. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1311–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeli B, McLaughlin P, Pro B, Samaniego F, Gayed I, Hagemeister F, Romaguera J, Cabanillas F, Neelapu SS, Banay R, Fayad L, Wayne Saville M, Kwak LW. Prospective trial of targeted radioimmunotherapy with Y-90 ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin) for front-line treatment of early-stage extranodal indolent ocular adnexal lymphoma. Annals of Oncology. 2009;20:709–714. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri AJM, PM, Guidoboni M, Conciliis CD, Resti AG, Mazzi B, Lettini AA, Demeter J, Dell’Oro S, Doglioni C, Villa E, Boiocchi M, Dolcetti R. Regression of ocular adnexal lymphoma after Chlamydia psittaci-eradicating antibiotic therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:5067–5073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Du MQ, Doglioni C, Resti AG, Politi LS, De Conciliis C, Radford J, Bertoni F, Zucca E, Cavalli F, Ponzoni M. Ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: an intriguing model for antigen-driven lymphomagenesis and microbial-targeted therapy. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19:835–846. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JA, Yang WI, Zukerberg LR, Wotherspoon AC, Arnold A, Harris NL. CD5+ extranodal marginal zone B-cell (MALT) lymphoma. A low grade neoplasm with a propensity for bone marrow involvement and relapse. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1996;105:31–37. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry JA, Fung CY, Zukerberg L, Lucarelli MJ, Hasserjian RP, Preffer FI, Harris NL. Lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: A study of 353 cases. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2007;31:170–184. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213350.49767.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252–260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<252::aid-cncr2820290138>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung CY, Tarbell NJ, Lucarelli MJ, Goldberg SI, Linggood RM, Harris NL, Ferry JA. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: clinical behavior of distinct World Health Organization classification subtypes. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2003;57:1382–1391. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Kojima M, Shioya M, Tamaki Y, Saitoh J, Sakurai H, Kitamoto Y, Suzuki Y, Niibe H, Nakano T. Treatment results of radiotherapy for malignant lymphoma of the orbit and histopathologic review according to the WHO classification. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2003;57:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00506-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Takahara S, Sekikawa T, Ito K, Nakada S, Yamazaki Y, Yamada J, Kobayashi M, Yamada H. Disseminated MALT lymphoma associated with macroglobulinemia. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2000;41:1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson DL, Gange SJ, Rose NR, Graham NM. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1997;84:223–243. doi: 10.1006/clin.1997.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Rose GE, Bunce C, Wright JE, Cree IA, Plowman N, Lightman S, Moseley I, Norton A. Histological features of ocular adnexal lymphoma (REAL classification) and their association with patient morbidity and survival. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2000;84:907–913. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Rose GE, Bunce C, Cree I, Norton A, Plowman PN, Moseley I, Wright JE. Clinical features associated with survival of patients with lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Eye (Lond) 2003;17:809–820. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles DM, Jakobiec FA, McNally L, Burke JS. Lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma occurring in the ocular adnexa (orbit, conjunctiva, and eyelids): a prospective multiparametric analysis of 108 cases during 1977 to 1987. Human Pathology. 1990;21:959–973. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Moritani S. High incidence of autoimmune disease in Japanese patients with ocular adnexal reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2007;144:148–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota T, Moritani S, Yoshino T, Nagai H, Terasaki H. Ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;145:1002–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le QT, Eulau SM, George TI, Hildebrand R, Warnke RA, Donaldson SS, Hoppe RT. Primary radiotherapy for localized orbital MALT lymphoma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2002;52:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Kim MK, Lee KH, Hyun MS, Chung HS, Kim DS, Shin SO, Cho HS, Bae SH, Ryoo HM. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Annals of Hematology. 2005;84:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margo CE, Mulla ZD. Malignant tumors of the orbit. Analysis of the Florida Cancer Registry. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(98)92107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JM, ML, Dennis J, Byrne GE, Jr, Ruiz P, Dubovy SR, Lossos IS. Ocular Adnexal Lymphoma: no evidence for bacterial DNA associated with lymphoma pathogenesis. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;142:246–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvie PA, McNab A, Francis IC, Fox R, O’Day J. Ocular adnexal lymphoproliferative disease: a series of 73 cases. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 2001;29:387–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.d01-18.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros LJ, Harmon DC, Linggood RM, Harris NL. Immunohistologic features predict clinical behavior of orbital and conjunctival lymphoid infiltrates. Blood. 1989;74:2121–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Vincent-Salomon A, Dendale R, Asselain B, Arnaud P, Fourquet A, Desjardins L, Plancher C, Validire P, Chaoui D, Levy C, Decaudin D. Ophthalmologic and intraocular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a large single centre study of initial characteristics, natural history, and prognostic factors. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2004;22:143–158. doi: 10.1002/hon.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier J, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Dendale R, Vincent-Salomon A, Asselain B, Arnaud P, Nemati F, Fourquet A, Desjardins L, Plancher C, Levy C, Chaoui D, Validire P, Decaudin D. Conjunctival low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a large single-center study of initial characteristics, natural history and prognostic factors. Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2006;47:1295–1305. doi: 10.1080/10428190500518966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moslehi R, Devesa SS, Schairer C, Fraumeni JF., Jr Rapidly increasing incidence of ocular non-hodgkin lymphoma. Journal of The National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:936–939. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata M, Matsuno Y, Takenaka T, Kobayashi Y, Takeyama K, Yokozawa T, Tobinai K. B-cell lymphoma accompanying monoclonal macroglobulinemia with features suggesting marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. International Journal of Hematology. 1997;65:405–411. doi: 10.1016/s0925-5710(96)00565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam H, Ahn YC, Kim YD, Ko Y, Kim WS. Prognostic significance of anatomic subsites: results of radiation therapy for 66 patients with localized orbital marginal zone B cell lymphoma. Radiotherapy & Oncology. 2009;90:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raderer M, Wohrer S, Streubel B, Troch M, Turetschek K, Jager U, Skrabs C, Gaiger A, Drach J, Puespoek A, Formanek M, Hoffmann M, Hauff W, Chott A. Assessment of disease dissemination in gastric compared with extragastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma using extensive staging: a single-center experience. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:3136–3141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo A, Raez LE, Byrne GE, Jr, Johnson T, Ossi P, Benedetto P, Hamilton K, Whitcomb CC, Cassileth PA. Is central nervous system prophylaxis necessary in ocular adnexal lymphoma? Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 1998;9:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose NR, Mackay IR. The Autoimmune Diseases. 3. Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosado MF, Byrne GE, Jr, Ding F, Fields KA, Ruiz P, Dubovy SR, Walker GR, Markoe A, Lossos IS. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107:467–472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song EK, Kim SY, Kim TM, Lee KW, Yun T, Na II, Shin H, Lee SH, Kim DW, Khwarg SI, Heo DS. Efficacy of chemotherapy as a first-line treatment in ocular adnexal extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19:242–246. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sretenovic M, Colovic M, Jankovic G, Suvajdzic N, Mihaljevic B, Colovic N, Todorovic M, Atkinson HD. More than a third of non-gastric malt lymphomas are disseminated at diagnosis: a single center survey. European Journal of Haematology. 2009;82:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic A, Lossos IS. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Blood. 2009;114:501–510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh CO, Shim SJ, Lee SW, Yang WI, Lee SY, Hahn JS. Orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT: radiotherapy results and clinical behavior. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 2006;65:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TJ, Valenzuela AA. Imaging features of ocular adnexal lymphoproliferative disease. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:1189–1195. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow SHCE, Harris NL. WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto K, Kaneko A, Suzuki S, Sekiguchi N, Maruyama D, Kim SW, Watanabe T, Kobayashi Y, Kagami Y, Maeshima A, Matsuno Y, Tobinai K. Long-term follow-up results of no initial therapy for ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma. Annals of Oncology. 2006;17:135–140. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto K, Kaneko A, Suzuki S, Sekiguchi N, Watanabe T, Kobayashi Y, Kagami Y, Maeshima AM, Matsuno Y, Tobinai K. Primary ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a long-term follow-up study of 114 patients. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;37:337–344. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieblemont C, Berger F, Dumontet C, Moullet I, Bouafia F, Felman P, Salles G, Coiffier B. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is a disseminated disease in one third of 158 patients analyzed. Blood. 2000;95:802–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK. Low-grade non-hodgkin lymphomas. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2007;17:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, Wells W, Hodgson DC, Sun A, Crump M, Patterson BJ. Localized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:4157–4164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno T, Isobe K, Shikama N, Nishikawa A, Oguchi M, Ueno N, Itami J, Ohnishi H, Mikata A, Ito H. Radiotherapy for extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue originating in the ocular adnexa: a multiinstitutional, retrospective review of 50 patients. Cancer. 2003;98:865–871. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez R, Finn WG, Ross CW, Singleton TP, Tworek JA, Schnitzer B. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia caused by extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a report of six cases. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2001;116:683–690. doi: 10.1309/6WPX-66CM-KGRH-V4RW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White WL, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Grove AS., Jr Ocular adnexal lymphoma. A clinicopathologic study with identification of lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1994–2006. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo JM, Tang CK, Rho MS, Lee JH, Kwon HC, Ahn HB. The clinical characteristics and treatment results of ocular adnexal lymphoma. Korean Journal of Ophthalmol. 2006;20:7–12. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2006.20.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotherspoon AC, Diss TC, Pan LX, Schmid C, Kerr-Muir MG, Lea SH, Isaacson PG. Primary low-grade B-cell lymphoma of the conjunctiva: a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type lymphoma. Histopathology. 1993;23:417–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Galieni P, Martelli M, Poletti V, Zaja F, Molica S, Zaccaria A, Cantonetti AM, Gentilini P, Guardigni L, Gherlinzoni F, Ribersani M, Bendandi M, Albertini P, Tura S. Nongastrointestinal low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: analysis of 75 patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:1254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]