SUMMARY

Accumulating structural studies of viral fusion glycoproteins have revealed unanticipated structural relationships between unrelated virus families and allowed the grouping of these membrane fusogens into three distinct classes. Here we review the newly identified group of class III viral fusion proteins, whose members include fusion proteins from rhabdoviruses, herpesviruses and baculoviruses. While clearly related in structure, the class III viral fusion proteins exhibit distinct structural features in their architectures as well as in their membrane-interacting fusion loops, which are likely related to their virus-specific differences in cellular entry. Further study of the similarities and differences in the class III viral fusion glycoproteins may provide greater insights into protein:membrane interactions that are key to promoting efficient bilayer fusion during virus entry.

INTRODUCTION

Three classes of viral membrane fusion proteins have been identified in large part based on the key structural features of the proteins. All class I fusion proteins have structural features that resemble the influenza-virus haemagglutinin (HA), whose structure was determined in 1981 [1]. The core of the class I protein fusogenic domain is predominantly composed of α-helices, which contain N-terminally located hydrophobic fusion peptides, and in the post-fusion conformation the fusogenic domain is characterized by a prominent trimeric α-helical coiled-coil. In 1995, the structure of the fusion protein E of tick borne encephalitis virus was solved [2], and it revealed a protein with a novel fold, radically different from the class I proteins. E and other proteins that are assigned to class II are mostly made of β-sheets, their fusion peptides are located in internal loops, and unlike class I proteins, which remain trimeric, their conformational change involves a change in oligomeric state from pre-fusion dimers to post-fusion trimers. (Readers are advised to consult reviews [3-5] for a more comprehensive description of the structural and functional features of class I and II fusion proteins).

In 2006 the structures of the ectodomains of the fusogenic proteins G (G) of Vesicular Stomatatis virus (VSV) [6], and glycoprotein B (gB) of Herpes Simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) [7] were determined, and revealed an unanticipated structural homology between the two proteins, which carry no sequence homology and belong to, respectively, a negative-strand RNA and a DNA virus. Based on previous electron microscopy observations indicating that the post-fusion trimers of G are ~12 nm long [8], just as observed in the crystal structure, and because of the folded-back organization of G, typical for the post-fusion conformation of class I and II fusion proteins, the crystallized form of G was proposed to correspond to the post-fusion conformation. By analogy the structure of the gB ectodomain was postulated to represent a post-fusion state as well.

The secondary structure connectivity and organization of domains of G and gB exhibit a remarkable similarity, and while they contain a central trimeric coiled-coil, a hallmark of class I proteins in their post-fusion states, three of their domains are predominantly made of β-sheets and their fusion peptide is internal, typical of class II proteins. Because of the distinct properties of VSV G and HSV-1 gB, which combine some of the features of class I and II fusion proteins, it was proposed that they define a novel class III of fusion proteins [9]. Just recently, structures of baculovirus fusion protein gp64 [10] and gB from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [11] were solved and due to the structural homology with the post-fusion conformation of G and HSV-1 gB, they have been added to the class III group of fusion proteins. This review aims at describing the structural and functional features of class III fusion proteins, raising questions that need to be answered in order to deepen our understanding of the class III protein membrane fusion mechanism within the context of very different viruses and entry processes.

Molecular architecture of class III fusion proteins

VSV G is the only class III fusion protein for which the structures of both the pre- and post-fusion states are available [6,12]. The structures determined for the other three class III members, HSV-1 gB [7], EBV gB [11] and baculovirus gp64 [10], have been proposed to represent their post-fusion conformations, based on the structural homology with the post-fusion conformation of G. The comparative analysis of the structural features of class III proteins presented here will therefore focus on the description and comparison of the postulated post-fusion trimeric conformations.

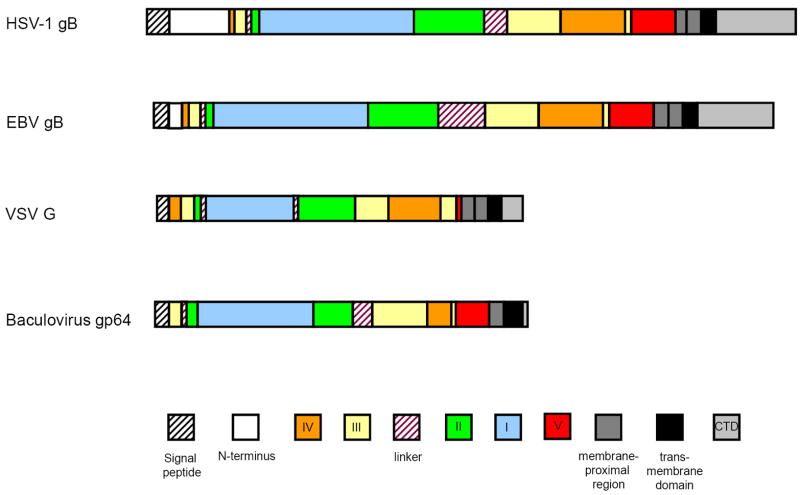

Class III fusion proteins are composed of 5 domains which give rise to a molecular architecture very distinct from any reported class I or class II fusion protein (Figure 1). Class III fusion proteins share a common structural organization of their domains. They all contain a fusion module (domain I), which is, as a whole, inserted between two β-strands of a domain with a pleckstrin-like (PH) fold (domain II). The domain II is in turn embedded within the largely helical domain III, which itself is embedded in domain IV (Figure 2). At the C-terminus of domain IV is the extended domain V, which connects the domain IV with the membrane-proximal regions that precede the transmembrane domain (Figure 1).

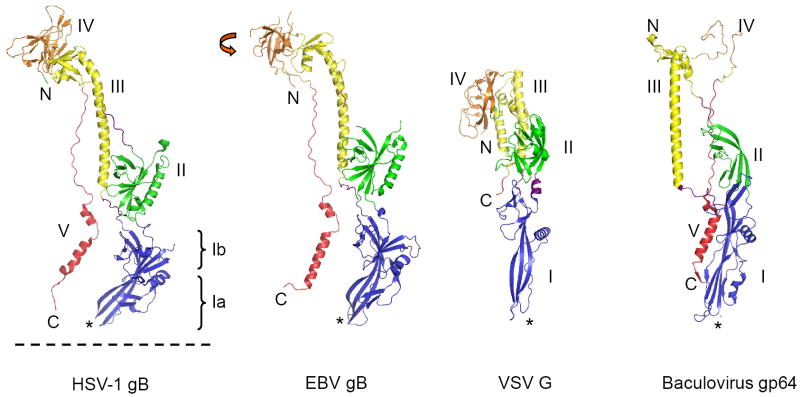

Figure 1. Post-fusion conformations of class III fusion proteins.

Class III fusion ectodomains form trimers, and only monomers are shown here. Domains are colored as: I (blue), II (green), III (yellow), IV (orange), V (red) and linkers (violet). N- and C-termini are marked with, respectively, letters “N” and “C”. Fusion loops are labeled with a star sign (*). C-termini and fusion loops are pointing in the same directions, as found in the post-fusion conformations of class I and class II fusion proteins. C-termini are followed by membrane-proximal regions and transmembrane domains. Dashed line represents the anticipated location of membrane. Orange arrow in EBV gB illustrates rotation of domain IV compared to the position of domain IV HSV-1 gB. Domain IV in gp64 is largely disordered.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the domain organization of class III fusion proteins.

Color coding of domains is the same as used in Figure 1.

The ectodomains of class III fusion proteins form trimers in which protomers wrap around each other resulting in elongated, rod-like shape molecules, which vary significantly in size (Figure 2, Table 1). The smallest ectodomain is the ~440 residue long VSV G ectodomain, and the largest and the most complex is the ~740 residue long HSV-1 gB ectodomain (Table 1). Despite such high variability in the length, the secondary structure topology exhibits notable similarity.

Table 1.

Domain organization of class III fusion proteins

| HSV-1 gB | EBV gB | VSV G | Baculovirus gp64 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane topology of the full-length proteins | ||||

| Signal sequence | 1-30 | 1-22 | 1-16 | 1-20 |

| Ectodomain | 31-774 | 23-732 | 17-462 | 21-481 |

| Membrane-proximal regions | 731-746 | 689-704 | 421-462 | 461-481 |

| 752-771 | 710-729 | |||

| Transmembrane domain | 775-795 | 733-753 | 463-482 | 482-504 |

| C-terminal domain | 796-904 | 754-857 | 483-511 | 505-512 |

| Domain boundaries of crystallized ectodomains | ||||

| Crystallized ectodomain | 31 - 730 | 23 - 685 | 1 - 422 | 21 - 499 |

| (17–438)1 | ||||

| Size of crystallized trimer (Å) | 160 × 85 | 160 × 70 | 125 × 60 | 150 × 55 |

| I | 154 - 363 | 89 - 294 | 53 - 172 | 60 - 217 |

| II | 142 - 153 | 77 - 88 | 36 - 46 | 44 - 59 |

| 364 - 459 | 295 - 390 | 181 - 258 | 218 - 271 | |

| III | 117 - 133 | 52 - 68 | 18 - 35 | 22 - 39 |

| 500 - 572 | 455 - 527 | 259 - 309 | 298 - 373 | |

| 661 - 669 | 617 - 624 | 384 - 405 | 408 - 412 | |

| IV | 111 - 116 | 42 - 51 | 1 - 17 | 374 - 407 |

| 573 - 660 | 528 - 616 | 310 - 383 | ||

| V | 670 - 725 | 625 - 679 | 406 - 4462 | 413 - 460 |

| Linkers | 134 - 141 | 69 - 76 | 47 - 52 | 40 - 43 |

| 460 - 499 | 391 - 454 | 173 – 180 | 272 – 297 | |

| (492 - 499)3 | (447 - 454)3 | (288 – 297)3 | ||

| Residues in putative fusion loops | WY | HR | WY | GGSLDPNT |

| WLIW4 | RVEA | YA | NNNHFA | |

Domain boundaries are reported as in the original articles, and the domain nomenclature, initially reported for HSV-1 gB, is applied to all proteins. Numbering of residues corresponds to that of unprocessed proteins (with the exception of VSV G domain boundaries (see remark 1)).

Indicates the residues of the crystallized VSV G ectodomain numbered according to the unprocessed protein. Domain boundaries for G reported in this table, as well as in the original article, correspond to the residues of the mature protein, which is produced after cleavage of the 16-residue long signal peptide.

The crystallized G ectodomain was obtained by cleaving the protein of the virus by thermolysin at residue S422. The last residues of domain V that could be resolved in the pre- and post-fusion structures, respectively, are A413 and I410.

Indicates the linker residues that could be resolved in the X-ray structures.

WY and WLIW are wild type residues found in EBV gB. The crystallized variant contained HR and RVEA residues in place of the wild type residues.

Domain I (the fusion domain) forms an extended β-sheet structure at the base of the trimeric spikes, and contains at its tip two loops proposed to form the bipartite fusion peptide of class III proteins. The complexity of the molecular architecture of domain I varies. In G, it has a six-stranded and a three-stranded β-sheet. In gB and gp64, it can be divided into two subdomains – Ib, a β-barrel in gp64 and a β-sandwich in gB (the latter being similar to a PH domain), and Ia, which bears at its base the fusion loops (Figure 1).

Domain II of all class III fusion proteins contains one or more anti-parallel β-sheets, and in G and gB has a fold of PH domains. PH domains have been reported to serve as binding modules for specific phospholipid components in cell membranes, but can also provide binding surfaces for protein ligands (reviewed in [13,14]). It has therefore been hypothesized that the PH modules in domain I and domain II of gB may function as binding sites for other membrane proteins involved in fusion and entry [7,11].

The hallmark of domain III is the long central α-helix, which forms a trimeric coiled coil with the helices provided by the other two protomers. Domain III of gp64 is swapped between subunits when compared to its position in gB and G (Figure 1). In gB and gp64 the central helix is followed by a shorter helix and a four-stranded β-sheet, while the analogous sheet in G is classified as a component of domain IV. In addition to the trimerization contacts established through the trimeric coiled coil, the β-sheets of domain III of gB and gp64 contain strands of, respectively, two and three protomers, thereby further contributing to the trimerization surface.

Domain IV is made entirely of β-sheets and shows a high variability in size and structural arrangement. In gp64 it is poorly defined suggesting a certain degree of flexibility. In EBV gB it is rotated with respect to the rest of the molecule when compared to HSV-1 gB (Figure 1) and is partially disordered, supporting the idea that it may be intrinsically flexible. Whether the flexibility of domain IV is important for function remains to be determined.

Domain V is composed of an extended segment that in gB and gp64 inserts between the other two protomers within the trimer, and forms an extensive trimerization interface. In the crystallized G ectodomain most of domain V is removed by thermolysin, which was used to cleave the protein of VSV virions (Table 1). In the pre-fusion form of G the last 6 C-terminal residues form an α-helix, while the same region is unstructured in the post-fusion form. Peptides corresponding to domain V of rabies G protein are poorly structured in aqueous solutions, but adopt helical conformation in the presence of trifluoroethanol [15].

Fusion peptides of class III fusion proteins

The fusion peptide of VSV G was suggested to be bipartite based on the homology with the fusion peptide of hemorrhagic septicemia virus [16], another rhabdovirus. One of the internal fusion loops of G had been located by mutagenesis [17,18] and photolabeling studies [19], and indeed, the structure of the G ectodomain [6] revealed two exposed loops at the tip of the molecule, projected in a ‘straight’ conformation resembling what has been observed for the fusion peptide of class II fusion proteins. The residues found in the VSV G fusion loops are WY72-73 and YA116-117, with W72 being the most critical residue for G-mediated fusion [20]. Based on the structural homology between G and HSV-1 gB, the analogous loops that connect β-strands at the tip of domain I in HSV-1 gB, VWFGHRY173-179 and RVEAFHRY258-265, were proposed to form the putative fusion peptide of gB [7]. Mutagenesis experiments demonstrated the importance of HSV-1 gB residues W174, Y179, A261 for fusion, supporting the idea that the two loops form the fusion peptide of HSV-1 gB. At the same time, recombinant ectodomains of EBV gB were shown to form, instead of the simple trimers observed for HSV-1 gB, distinct rosette structures, typically found in preparations of class I and II fusion proteins in their post-fusion states [21]. Rosette formation is driven by hydrophobic interactions of the exposed fusion peptides [22-25], and the sequences of the putative fusion loops in EBV gB, GWYA111-114 and GWLIWTY192-198, are more abundant in hydrophobic amino acids, consistent with their potential to cause the aggregation. Residues WY112-113 and WLIW193-196 were shown to be indispensable for the ability of EBV gB to mediate fusion in a cell:cell fusion assay, consistent with their functional importance [26]. The substitution of the hydrophobic EBV WY and WLIW residues for the analogous hydrophilic HSV-1 residues, HR and RVEA, while abrogating the ability of the protein to mediate fusion, allowed production of trimeric protein which was then crystallized, enabling the determination of the structure of EBV gB ectodomain [11].

Residues forming the analogous fusion loop structures in gp64 are GGSLDPNT79-86 and NNNHFA149-154 [10]. The importance of the gp64 hydrophobic residues L82, F153 and A154, but also polar residues S81 and D83 was demonstrated by the inability of gp64 variants containing substitutions at these positions to mediate syncytium formation [10]. Moreover substitutions of F153 and H156 for alanine in gp64 resulted in virus that exhibited significantly decreased binding to cells, indicating that the fusion loop residues may also play a role in establishing interactions with a still unidentified gp64 cellular receptor [27].

Fusion peptides of class I and II fusion proteins are highly conserved sequences (reviewed in [28]), typically rich in small apolar residues such as L, I, A and G which have high propensity to insert into membranes. In the case of class III fusion proteins the situation appears more complex and may indicate distinct requirements that each of the fusion proteins has to fulfill in order to function in a virus-specific context. The regions that form putative fusion loops in gB of herpesviruses are not conserved. Fusion loops of HSV-1 gB (HR, RVEA) are not abundant in hydrophobic residues compatible with membrane penetration, while the EBV gB residues (WY, WLIW) more resemble the sequences that would be likely to insert into membranes. Regardless of the effect of the amino acid composition, the conformation of the HSV-1 and EBV gB fusion loops is tilted with respect to the anticipated membrane location (Figure 1), so they seem to be in a conformation suboptimal for membrane insertion (this is as opposed to the more straight loops of VSV G). But even the hydrophobic fusion loop residues of G, WY and YA, seem unlikely to insert into the lipid bilayer deeper than 8.5 Å, due to the presence of charged residues lining the edges of the fusion loops and thus hindering their full insertion [6].

The fusion loops of G proteins of rhabdoviruses all contain at least one W or Y residue. The fusion loops of gp64 of baculoviruses, and the homologous gp75 of Thogoto and Dhori virus, are conserved [10] and contain F and A residues which have high propensity for insertion into the bilayer [29]. Aromatic polar residues, such as W and Y, and histidine residues, are typically found at membrane interfaces [29,30], suggesting that while the fusion loops of class III proteins may not penetrate the membranes, as thought for some class I and II proteins fusion peptides, they may be interacting with them in a manner that is sufficient to bind to or destabilize the bilayer and promote fusion.

The identification of the residues forming putative fusion loops of HSV-1 gB [31], EBV gB [26] and baculovirus gp64 [10] has been possible because of the structural homology of the class III fusion proteins. While the importance of the putative fusion loop residues for fusion has been assessed, further experiments need to be done to evaluate the interactions of these residues with membrane lipids and the effect these interactions may have on membrane properties.

Membrane-proximal regions of class III proteins

G and gB proteins contain ~40 residue long membrane-proximal regions (Table 1) whose abundance in hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids suggests that they might interact with membranes and participate in fusion. In VSV G, the deletions of these so-called stem regions results in a dramatic decrease of G-mediated cell:cell fusion and viral infectivity [32]. Moreover, when grafted to another fusion protein such as HA of influenza, the VSV G stem regions potentiate the activity of the heterologous protein and can drive membrane merger to the hemifusion intermediate [33]. The stem regions of G also play a role in viral budding; recombinant VSV particles containing stem regions as short as 12 residues (and expressed in a construct together with the transmembrane domain and a short C-terminal domain (CTD)) can be produced at levels comparable to the wild type virus. It was proposed that the stem regions of G promote viral maturation by inducing a curvature in membranes, close to the sites of virus budding [34].

Baculovirus gp64 contains a ~20 residue long membrane-proximal segment that connects the end of its domain V to the transmembrane region and a 7 residue C-terminal tail domain (CTD). Deletion of the gp64 CTD does not significantly affect the cell-surface expression and the ability of the truncated protein to mediate fusion, but does reduce the baculovirus titers to ~50%, indicating involvement of the CTD in virus budding [35]. Baculovirus budding defects introduced by deletions in the gp64 ectodomain can be efficiently overcome by co-expression of the mutated gp64 proteins with VSV G stem constructs containing the G stem, transmembrane domain and the CTD [27].

The crystallized G and gp64 ectodomains contained a part of the membrane-proximal regions (Table 1), however these residues could not be fully resolved indicating flexibility (the C-terminus forms a short helix in the pre-fusion form of G). It is tempting to speculate that the hydrophobic residues from membrane-proximal regions play a direct role in promoting lipid mixing and fusion, nevertheless this remains to be investigated further.

Conformational change of class III fusion proteins

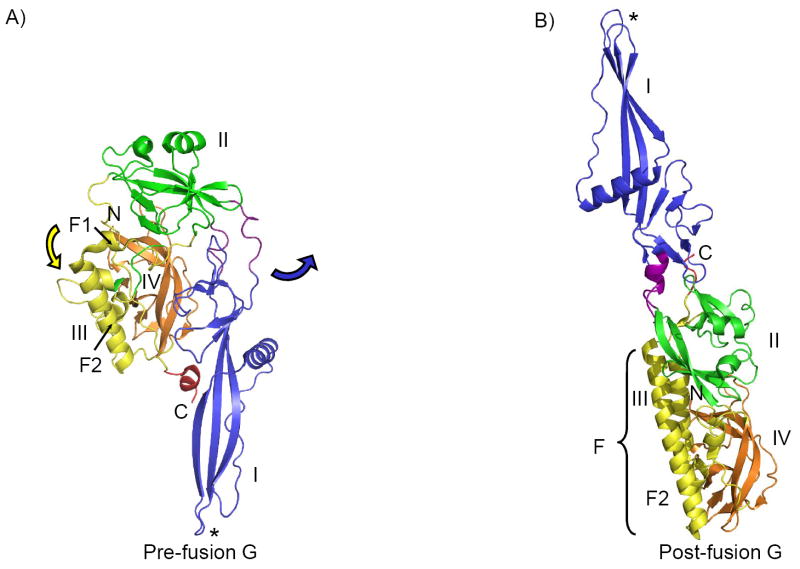

G is the only class III fusion protein whose pre-fusion structure is known [12]. Pre-fusion G trimers are compact, ~8.5 nm in length, and form spikes that resemble a tripod. The fusion loops point toward the viral membrane in the pre-fusion form. During the conformational change that occurs upon low pH exposure, the domains of G radically change their position and orientation as a result of rearrangements that occur in the linker regions. Domain I, carrying the fusion loops, and the transmembrane domain move ~16 nm from one end of the molecule to the opposite (reviewed in [36]). Only domain III undergoes significant refolding, while the other domains retain their folds (Figure 3). The extension of the central helix F (domain III) and repositioning of the C-terminal helices of domain V to insert into crevices formed by other two protomers in the post-fusion form are reminiscent of the structural changes observed during refolding events of class I fusion proteins F of paramyxoviruses and hemagglutinin of influenza [36-38].

Figure 3. Conformational change in VSV G.

The ectodomain of G has been crystallized in its pre-fusion (panel A) and post-fusion (low-pH) (panel B) state. The conformational change results in flipping of domain I, carrying the fusion loops, and the C-terminus, to the opposite side of the molecule, relative to domain IV and helix F2 of domain III, which can be viewed as a rigid body and are shown in the same orientation in panels A and B. During the structural rearrangement, domains I, II and IV retain their folds, while domain III (yellow) undergoes significant refolding (central helix F2 is prolonged into the longer helix F in post-fusion form, through recruitment of helix F1, as indicated by the yellow arrow in panel A). The linker or hinge regions, which suspend domain I off the rest of the molecule (residues 47-52 and 173-180), are shown in violet. These regions undergo structural changes important for the initial stage of the conformational change, during which domain I separates from the C-terminus, swings out and rotates 94° relative to domain II (the direction of movement is indicated by the blue arrow in panel A). This is followed by repositioning of domain IV on top of domain III, and results in the more extended post-fusion conformation.

It is proposed that histidine residues in G act as pH sensors, and that deprotonation of these residues leads to the separation of domain I from the C-terminus and therefore initiates the conformational change [12]. There are also a number of conserved histidine residues in the gp64 of baculoviruses and a similar mechanism for pH-switching has been suggested [10]. A conformational change has been reported for gB and gH/gL from murid herpesvirus 4 [39,40], but additional studies are needed to investigate if a conformational change occurs in gB and gH/gL of other herpesviruses. Also, since herpesviruses enter cells by fusion with plasma membranes and in response to receptor binding, not by a pH-triggered mechanism, it remains to be determined whether the conformational changes of VSV G occur in gB.

Entry mechanisms of class III fusion proteins

Rhabdoviruses and budded virions of baculoviruses enter cells by endocytosis. G and gp64 are the major component of the viral envelope, and the sole fusogenic proteins which are triggered to induce the fusion in the low pH environment of endosomes [41,42]. What distinguishes G and gp64 from any other fusion protein is that they can undergo a reversible conformational change [43-45], unlike class I and class II fusion proteins, for which the post-fusion conformation is thermodynamically more stable at all pH values, and the conformational rearrangement is effectively irreversible. VSV exposure to low pH inactivates the virus, but the fusion activity can be fully recovered when the pH is raised [46]. In the case of gp64, it seems that even though the protein can be reactivated to mediate fusion after acidification [44], exposure of the virus to pH 4.5 irreversibly neutralizes its infectivity [45]. It has been proposed that the reversibility of the conformational change allows G to avoid unspecific activation during transport through the acidic Golgi vesicles [47], and the same may apply to gp64.

Herpesviruses enter cells by fusion with the plasma membranes, although there are reports of entry through endocytosis, which can be pH-dependent or pH-independent (reviewed in [48]). gB is not the sole fusogen of herpesviruses, and a heterodimeric complex of glycoproteins H and L (gH/gL) together with gB forms the fusion apparatus in all herpesviruses. There have been multiple reports showing that both gB and gH/gL have intrinsic fusogenic properties [48] and, for example, a truncated variant of EBV gB can mediate fusion in a cell:cell fusion assay in a gH/gL-independent manner [49]. Moreover, some insight has been gained into the roles played by gB and gH/gL in a study that demonstrated that gH/gL causes lipid mixing indicative of hemifusion, while gB was required for full fusion to occur [50].

While there is no clear consensus on which factors act as cellular receptors for VSV [51,52] and baculoviruses, the receptor-binding proteins of herpesviruses, such as gD in HSV-1 and gp42 in EBV, are well described [53]. Binding of these proteins to the cellular receptors is essential for fusion to occur. In HSV-1, gD interacts with both gB and gH/gL, and triggers formation of the core fusion machinery made of gB and gH/gL [54]. How the activation signal gets transferred from the receptor-binding proteins to the fusion proteins of herpesviruses, how general the mechanism is, and why herpesviruses have evolved such complex machinery are questions that still remain to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the T. Jardetzky, R. Longnecker and F. Rey laboratories for helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Public Health Service grants AI076183 and CA117794 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature. 1981;289:366–373. doi: 10.1038/289366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rey FA, Heinz FX, Mandl C, Kunz C, Harrison SC. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature. 1995;375:291–298. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kielian M, Rey FA. Virus membrane-fusion proteins: more than one way to make a hairpin. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:67–76. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **6.Roche S, Bressanelli S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y. Crystal structure of the low-pH form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2006;313:187–191. doi: 10.1126/science.1127683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **7.Heldwein EE, Lou H, Bender FC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science. 2006;313:217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.1126548. The above two articles were published at the same time, and are the first reports of the post-fusion structures of the class III viral fusion proteins from respectively, a herpesvirus and a rhabdovirus.

- 8.Gaudin Y, Ruigrok RW, Knossow M, Flamand A. Low-pH conformational changes of rabies virus glycoprotein and their role in membrane fusion. J Virol. 1993;67:1365–1372. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1365-1372.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steven AC, Spear PG. Biochemistry. Viral glycoproteins and an evolutionary conundrum. Science. 2006;313:177–178. doi: 10.1126/science.1129761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *10.Kadlec J, Loureiro S, Abrescia NG, Stuart DI, Jones IM. The postfusion structure of baculovirus gp64 supports a unified view of viral fusion machines. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1484. Authors describe the post-fusion structure of the class III fusion protein from another unrelated virus, baculovirus, and identify the residues that form putative fusion loops in gp64.

- *11.Backovic M, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. Structure of a trimeric variant of the Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810530106. In press. This report describes the post-fusion structure of gB from a gamma herpesvirus, Epstein-Barr virus, in its post-fusion conformation and gives overview of similarities and differences with the other class III fusion proteins.

- **12.Roche S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y, Bressanelli S. Structure of the prefusion form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2007;315:843–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1135710. This is the only pre-fusion structure of a class III fusion protein.

- 13.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemmon MA. Pleckstrin homology domains: not just for phosphoinositides. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:707–711. doi: 10.1042/BST0320707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maillard A, Domanski M, Brunet P, Chaffotte A, Guittet E, Gaudin Y. Spectroscopic characterization of two peptides derived from the stem of rabies virus glycoprotein. Virus Res. 2003;93:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(03)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaudin Y, de Kinkelin P, Benmansour A. Mutations in the glycoprotein of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus that affect virulence for fish and the pH threshold for membrane fusion. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 5):1221–1229. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fredericksen BL, Whitt MA. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein mutations that affect membrane fusion activity and abolish virus infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:1435–1443. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1435-1443.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Ghosh HP. Characterization of the putative fusogenic domain in vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. J Virol. 1994;68:2186–2193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2186-2193.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrer P, Gaudin Y, Ruigrok RW, Graf R, Brunner J. Photolabeling identifies a putative fusion domain in the envelope glycoprotein of rabies and vesicular stomatitis viruses. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17575–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Belouzard S, Whittaker GR. Molecular architecture of the bipartite fusion loops of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G, a class III viral fusion protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6418–6427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Backovic M, Leser GP, Lamb RA, Longnecker R, Jardetzky TS. Characterization of EBV gB indicates properties of both class I and class II viral fusion proteins. Virology. 2007;368:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calder LJ, Gonzalez-Reyes L, Garcia-Barreno B, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Melero JA. Electron microscopy of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein and complexes that it forms with monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 2000;271:122–131. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connolly SA, Leser GP, Yin HS, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA. Refolding of a paramyxovirus F protein from prefusion to postfusion conformations observed by liposome binding and electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17903–17908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608678103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruigrok RW, Aitken A, Calder LJ, Martin SR, Skehel JJ, Wharton SA, Weis W, Wiley DC. Studies on the structure of the influenza virus haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2785–2795. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-11-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons DL, Vaney MC, Roussel A, Vigouroux A, Reilly B, Lepault J, Kielian M, Rey FA. Conformational change and protein-protein interactions of the fusion protein of Semliki Forest virus. Nature. 2004;427:320–325. doi: 10.1038/nature02239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Backovic M, Jardetzky TS, Longnecker R. Hydrophobic residues that form putative fusion loops of Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein B are critical for fusion activity. J Virol. 2007;81:9596–9600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00758-07. This is the first report that indicates the regions forming putative fusion loops of EBV gB by demonstrating the importance of these residues for the ability of gB to induce fusion in a cell:cell fusion assay.

- 27.Zhou J, Blissard GW. Identification of a GP64 subdomain involved in receptor binding by budded virions of the baculovirus Autographica californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J Virol. 2008;82:4449–4460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02490-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Earp LJ, Delos SE, Park HE, White JM. The many mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;285:25–66. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26764-6_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulmschneider MB, Sansom MS, Di Nola A. Properties of integral membrane protein structures: derivation of an implicit membrane potential. Proteins. 2005;59:252–265. doi: 10.1002/prot.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wimley WC, White SH. Partitioning of tryptophan side-chain analogs between water and cyclohexane. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12813–12818. doi: 10.1021/bi00166a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannah BP, Heldwein EE, Bender FC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Mutational evidence of internal fusion loops in herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. J Virol. 2007;81:4858–4865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02755-06. This is the first functional study that indicates residues forming putative fusion peptide of Herpes Simplex virus 1 gB.

- 32.Jeetendra E, Ghosh K, Odell D, Li J, Ghosh HP, Whitt MA. The membrane-proximal region of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G ectodomain is critical for fusion and virus infectivity. J Virol. 2003;77:12807–12818. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12807-12818.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeetendra E, Robison CS, Albritton LM, Whitt MA. The membrane-proximal domain of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein functions as a membrane fusion potentiator and can induce hemifusion. J Virol. 2002;76:12300–12311. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12300-12311.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robison CS, Whitt MA. The membrane-proximal stem region of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein confers efficient virus assembly. J Virol. 2000;74:2239–2246. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2239-2246.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oomens AG, Blissard GW. Requirement for GP64 to drive efficient budding of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology. 1999;254:297–314. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roche S, Albertini AA, Lepault J, Bressanelli S, Gaudin Y. Structures of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein: membrane fusion revisited. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1716–1728. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7534-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin HS, Wen X, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structure of the parainfluenza virus 5 F protein in its metastable, prefusion conformation. Nature. 2006;439:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillet L, Colaco S, Stevenson PG. Glycoprotein B switches conformation during murid herpesvirus 4 entry. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1352–1363. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83519-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillet L, Colaco S, Stevenson PG. The Murid Herpesvirus-4 gL regulates an entry-associated conformation change in gH. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Le Blanc I, Luyet PP, Pons V, Ferguson C, Emans N, Petiot A, Mayran N, Demaurex N, Faure J, Sadoul R, et al. Endosome-to-cytosol transport of viral nucleocapsids. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:653–664. doi: 10.1038/ncb1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blissard GW, Wenz JR. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J Virol. 1992;66:6829–6835. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6829-6835.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roche S, Gaudin Y. Characterization of the equilibrium between the native and fusion-inactive conformation of rabies virus glycoprotein indicates that the fusion complex is made of several trimers. Virology. 2002;297:128–135. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markovic I, Pulyaeva H, Sokoloff A, Chernomordik LV. Membrane fusion mediated by baculovirus gp64 involves assembly of stable gp64 trimers into multiprotein aggregates. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1155–1166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou J, Blissard GW. Mapping the conformational epitope of a neutralizing antibody (AcV1) directed against the AcMNPV GP64 protein. Virology. 2006;352:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaudin Y, Tuffereau C, Segretain D, Knossow M, Flamand A. Reversible conformational changes and fusion activity of rabies virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 1991;65:4853–4859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4853-4859.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaudin Y, Tuffereau C, Durrer P, Flamand A, Ruigrok RW. Biological function of the low-pH, fusion-inactive conformation of rabies virus glycoprotein (G): G is transported in a fusion-inactive state-like conformation. J Virol. 1995;69:5528–5534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5528-5534.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heldwein EE, Krummenacher C. Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7570-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McShane MP, Longnecker R. Cell-surface expression of a mutated Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein B allows fusion independent of other viral proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17474–17479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404535101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subramanian RP, Geraghty RJ. Herpes simplex virus type 1 mediates fusion through a hemifusion intermediate by sequential activity of glycoproteins D, H, L, and B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2903–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608374104. This study provides evidence for distinct roles that gB and gH/gL play in membrane fusion by showing that while gH/gL can induce membrane mixing indicative of hemifusion, gB is required, possibly in the next stage, to drive the fusion to completion.

- 51.Schlegel R, Tralka TS, Willingham MC, Pastan I. Inhibition of VSV binding and infectivity by phosphatidylserine: is phosphatidylserine a VSV-binding site? Cell. 1983;32:639–646. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coil DA, Miller AD. Phosphatidylserine is not the cell surface receptor for vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 2004;78:10920–10926. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10920-10926.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spear PG. Herpes simplex virus: receptors and ligands for cell entry. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atanasiu D, Whitbeck JC, Cairns TM, Reilly B, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Bimolecular complementation reveals that glycoproteins gB and gH/gL of herpes simplex virus interact with each other during cell fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18718–18723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707452104. This report demonstrates that gB and gH/gL interact and form a complex only upon binding of gD to its receptor, by using the bimolecular complementation assay which enabled the authors to detect the interactions during fusion.