Abstract

This paper reports the results of a 10-year follow-up of two variations of a couples group preventive intervention offered to couples in the year before their oldest child made the transition to kindergarten. 100 couples were randomly assigned to (1) a low-dose control condition, (2) a couples group meeting for 16 weeks that focused more on couple relationship issues among other family topics, or (3) a couples group meeting for 16 weeks that focused more on parenting issues among other family issues, with an identical curriculum to condition (2). Earlier papers reported that both variations of the intervention produced positive results on parent-child relationships and on the children’s adaptation to kindergarten and 1st grade, and that the groups emphasizing couple relationships also had additional positive effects on couple interaction quality. The present paper uses growth curve analyses to examine intervention effects extending from the children’s transition to kindergarten to the transition to high school – ten years after the couples groups ended. There were 6-year positive effects of the pre-kindergarten interventions on observed couple interaction and 10-year positive effects on both parents’ marital satisfaction and the children’s adaptation (hyperactivity and aggression). Discussion includes a focus on the implications of these results for family policy, clinical practice, and the need to include a couples focus in preventive interventions to strengthen family relationships and enhance children’s adaptation to school.

Keywords: prevention, group interventions, couple relationships, transition to high school

The transitions to kindergarten (Pianta, Rimm-Kaufman, & Cox, 1999) and to high school (Seidman, Aber, Allen, & French, 1996) are widely believed to represent important milestones for children, as they react to new settings with academic and social demands that present disequilibrating challenges. Difficulties experienced by substantial numbers of students in meeting these challenges have prompted the design of school-based interventions to make these passages easier to manage (Schulting, Malone, & Dodge, 2005). The fact that family risk and protective factors account for substantial proportions of variance in children’s academic and social adaptation to school (C. P. Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 2005) suggests that family-based interventions might also be helpful in facilitating children’s school transitions.

Until the last two decades, most of the literature linking family risk and protective factors and children’s emotional, social, and intellectual development focused primarily on mothers’ parenting behavior or parenting style. An emerging body of research began to demonstrate that fathers’ parenting also shows consistent links with a variety of child outcomes (Parke, 2002) and that couple relationship distress in both divorced and intact families has substantial negative effects on children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior and school achievement (Harold, Aitken, & Shelton, 2007). It seemed reasonable, then, in an intervention designed to reduce risk and enhance protective factors in children’s transition to school to include fathers and mothers, and to attempt to strengthen the relationship between them. We chose a group rather than a couple-by-couple intervention format, in part to demonstrate to couples undergoing the same life transition that they face similar challenges and stresses, and in part to provide social support during a time when most couples in urban settings undergo this transition on their own.

Earlier reports of this intervention begun in the year before the first child entered elementary school described positive outcomes when the children were in kindergarten and 1st grade. The present paper reports on a 10-year follow-up using growth curve analyses of data from follow-ups when the children were in 4th grade, and in 9th grade during the transition to high school.

Previous intervention findings

A randomized clinical trial of a group intervention for couples making the transition to first-time parenthood showed that a couples group meeting for 24 weeks from mid-pregnancy to 3 months postpartum prevented the decline in marital satisfaction experienced by the no-treatment controls until the first child had completed kindergarten (Schulz, Cowan, & Cowan, 2006). The present study, based on these encouraging findings, offered a couples group intervention for parents in the year before their first child entered kindergarten. Participant couples were randomly assigned to a 16-week couples group or a low-dose comparison condition (an opportunity to consult once a year for three years with the male-female staff team that conducted their initial interview). Those who agreed to participate in a couples group were further randomly divided into two variations of the groups in which the focus in the open-ended part of each meeting was on couple relationship issues or on parent-child issues. Curricula were otherwise identical.

Previously published results reported that, compared with parents in the low-dose comparison group, who showed no change in parenting style as observed in a laboratory playroom, fathers from the parenting-focused group were significantly warmer and more engaged with their children one year later, and mothers showed more structuring behavior when the child encountered difficult tasks. Despite these positive changes in parenting behavior for parents from the parenting-focused groups, no significant changes were observed in the handling of conflict between the parents. Nevertheless, the children of parents who participated in these groups were rated as showing more positive self-descriptions, assessed with the Berkeley Puppet Interview (Measelle, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 1998), and fewer withdrawn, anxious behaviors on the Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory (P. A. Cowan, Cowan, & Heming, 1995) completed by their teachers at the end of kindergarten and 1st grade.

There was a value-added impact of participating in the groups with a focus on couple relationship issues. By contrast with parents in the parenting-focused groups, these mothers and fathers showed reduced conflict in a problem-solving discussion from baseline to their children’s completion of kindergarten and greater effectiveness of both mothers’ and fathers’ parenting style. Furthermore, their children showed higher levels of achievement on individually administered achievement tests and lower levels of teacher-rated externalizing behavior at the end of kindergarten and 1st grade.

The central question for this paper is whether a couples group preventive intervention that was effective in enhancing the first child’s transition to elementary school would have long-term effects on the family and the child during the transition to high school. Two sets of findings led us to predict that the impact of the preschool intervention might hold up over this period. First, our previous Becoming a Family intervention study revealed effects on new parents’ marital satisfaction over a period of 5 years, with the gap between intervention and controls increasing over time (Schulz et al., 2006). Second, data from a number of studies support what Alexander and Entwisle called the trajectory hypothesis (Alexander, Entwisle, & Dauber, 1993); once children enter elementary school, their level of academic and social competence follows a trajectory in which they retain the same rank order through elementary and high school years. Because the intervention in this study facilitated adaptation to kindergarten and 1st grade, we expected that these advantages would be retained during the transition to high school.

The curriculum for both marital-focused and parenting-focused interventions (see below for more detail) was shaped by our 5-domain risk-protective model, with each domain having shown strong associations with children’s adaptation: (1) parents’ individual adaptation; (2) couple relationship quality; (3) relationship quality in parents’ families of origin; (4) quality of parents’ relationship with the child; (5) and the balance between life stressors and social supports. The curriculum addressed each of these topics and the measurement model assessed change in each domain. On the basis of earlier findings in this study and our prior study, we selected two parent domains and one child domain in which we expected to see intervention effects – quality of parents’ couple relationship, parenting style, and children’s adaptation.

METHOD

Participants

Recruitment

Participants were two-parent families living in 28 cities and towns within a 40-mile radius of the San Francisco Bay Area at the time they entered the study. Parents were recruited by the project team through flyers posted in nursery schools, daycare centers, pediatrician’s offices, and public service radio announcements. 198 couples met the initial selection criteria for participation in the study: (a) two parents living together and raising a first child who would enter kindergarten the next fall, and (b) completion of a 4-page questionnaire that included measures of marital satisfaction, depression, and worries about their children’s transition to school. Of 198 couples invited to an initial interview by one of the male-female group leader teams, 192 attended. In none of the recruitment materials had mention been made of the intervention component of the study, so that interested couples were not consciously seeking help for personal, couple, or family problems. They came to the initial interview expecting to participate in a study of family relationships and the factors that lead to children’s adaptation and success in elementary school.

At the end of the interview, we randomly offered 39 couples a low-dose intervention that served as a control condition -- a chance to consult with the interviewer team once a year for 3 years; 26 (67%) did so. Of the 153 couples offered a chance to participate in a couples group, 61 (40%) accepted, but 6 did not attend any group meetings or participate in any assessments. The 55 participant couples were randomly assigned to a marital-focused intervention (n=28) or a parenting-focused intervention (n=27) with the differential approach emphasized only during the open-ended portion of each evening. We believe that the difference in participation rates in the control and couples groups (67% vs. 40%) was attributable to the considerably smaller burden of time and effort asked of parents in the control condition. Finally, of those couples who declined to participate in a couples group, 19 agreed to be followed over time and served as a self-selected comparison group; they were included in their originally-assigned conditions (marital focus n=13; parenting focus n=6) for an intent-to-treat analysis.

There was little evidence of selection bias in study participants. There were no statistically significant differences on the initial 4-page questionnaire measures of marital satisfaction, depression, and worries about their children’s transition to school between (1) couples who came for the screening interview but later declined to participate further and (2) couples who joined the study.

Attrition in this study over 10 years was modest (P. A. Cowan et al., 2005). Of the 100 couples with pretest scores, 85% of the randomized controls participated in the 10-year follow-up when the children entered high school, 78% of the participants in the parenting-focused groups, 79% of the participants in the marital-focus groups, and 84% of those who refused our offer to participate in a group but agreed to complete the follow-up assessments. Because there were no statistically significant differences in the pretest measures of marital quality, parenting style, and child adaptation outcomes (see below) between those who continued in the study and those who dropped out, we conclude that there was little likelihood of attrition bias in the data presented in this 10-year follow-up. The current efficacy trial used data from the 81 couples who followed through with their initially randomized treatment condition. Results are then summarized for the 100 couple intent-to-treat sample.

Sample characteristics

At their entry into the study, mean age for fathers of a first child entering kindergarten was 37 years, for mothers, 36 years. Parents’ self-reports indicated that they identified as European American (84%), Asian American (7%), African American (6.6%), or Hispanic (2.5%). Income reports reveal that the sample was middle- to upper-income, with the median income at entry $73,000 per year (range $22,000 to $240,000), well above the median family income in the San Francisco Bay Area (1990 census) of $32,000 per year (included single parent families). About 15% of the sample earned below median household incomes in the counties from which they came. Over the course of the 10 years of the study, the parents’ divorce rate was approximately 2% of couples each year. In summary, the sample is considered “low-risk”, suitable for a preventive intervention study, and not representative of families in poverty.

The interventions

Both parenting-focused and marital-focused 16-week group meetings, held in rooms in the Psychology building, began with an open-ended 20–30-minute check-in that allowed individuals or couples to discuss family issues that had been raised in the previous meeting or come up during the week. The remaining time in the two hours was devoted to discussion of specific topics outlined in the curriculum -- based on a multidomain model that identified risk and protective factors in five domains (individual,, marital, parenting, three-generation, outside the family) that are associated with children’s well-being and behavior problems (see Introduction). Within each of these domains, specific discussion topics and exercises helped couples raise difficult issues in a safe and supportive setting. For example, in one exercise, participants looked at a “Who Does What?” questionnaire that asked partners to indicate how much each contributed to a number of household tasks, decisions, and child care tasks, and to indicate how they would like it to be. Another example involved a discussion of what specific parenting practices each partner wanted to carry over from the families they grew up in and which practices they were trying to avoid.

The curriculum topics of the two variations of the 16-week Couples groups were identical, but in the open-ended part of each evening, the leaders emphasized either the relationship between the parent partners (the marital focus) or the relationship between the parents and their child (the parenting focus) as they discussed issues that parents brought to the groups. For example, a disagreement between partners about whether to enforce consistent bedtime hours would be discussed in terms of discipline practices in the parenting-focused groups and of resolving the differences between partners in the marital-focused groups. The structured part of each evening’s discussion focused on at least one domain of the five-domain family risk model described above. The goal was not to teach specific communication skills or prescribe specific family practices, but to help couples collaborate on changes that would move them closer to being the kind of parents and partners they hoped to be. Although many couple-focused interventions emphasize communication skill training, the curriculum topics of these groups, covering five family domains, did not lend themselves to a didactic approach. In addition, we believe that allowing couples to grapple with the issues they bring to each session, within a structured framework, provides an optimal setting for couples to take what they need from the intervention. Fidelity to the intervention model was ensured in two ways: The marital-focus and parenting-focus groups were led by the same male-female teams throughout the project; the first two authors conducted supervision twice a month using taped segments of the group meetings.

Measures

The Schoolchildren and their Families Project involved baseline, pre-intervention assessments and four major follow-up assessments of the study families, all denoted by school-grade of the first child: Baseline (Pre-kindergarten), Post 1 (Kindergarten), Post 2 (1st grade), Post 3 (4th grade), Post 4 (9th grade). At each assessment time, self-reports of marital satisfaction were provided independently by both mothers and fathers. Couple communication was observed in a laboratory setting at four assessment periods (not in the 1st Grade year). Longitudinal data were collected from the children’s teachers in the fall and spring of kindergarten, and 1st, 4th and 9th grades, using a Child Behavior Adaptive Inventory to rate the adjustment of the study children and their classmates. Details of these measures are summarized below; more information about reliability and validity of the scales can be found in (P. A. Cowan et al., 2005).

Marital Adjustment and Satisfaction (MAT)

All mothers and fathers completed the Short Marital Adjustment Test (Locke & Wallace, 1959) at each assessment. This well established, widely used measure contains 16 items that assess partners’ satisfaction with their relationship.

Couple Communication

Couples were videotaped during two 10-minute conflict resolution tasks, based on procedures developed by Gottman and Levenson (1986), whose research procedures represent the most widely-used experimental paradigms for assessing couple conflict and interaction. Parents chose from separate lists of marital and parenting problems - one of each type - and then discussed it together, trying “to make some headway on the problem.” Nine ratings were developed, each using a 7-point scale focused on both individual and couple level behaviors. A Negative communication score summed the ratings of the couple’s amount of disagreement, mother’s negativity to father, fathers’ negativity to mother, and each parent’s level of defensiveness. A Positive couple communication score summed the ratings of couple teamwork, emotional connection, and each partner’s positive affect. Interrater reliabilities (intraclass correlations [ICCs]) on these scales ranged from .58 to .85, with a median of .71.

Parenting style

In separate mother-child and father-child sessions, parents interacted with the child for about 40 minutes around several age-appropriate challenging tasks (puzzles), teaching tasks (math concepts, emotion coaching discussions of videotapes), and games (building a world in the sand, story-telling, constructing “sculptures” from cardboard art pieces). These tasks were adapted from Block and Block (1980), and from our earlier study (C. P. Cowan & Cowan, 1992), and were chosen to provide a range of assessment contexts from highly structured and parent-dominated to open-ended and child-focused. As the children aged, they were presented with more difficult puzzles, sculptures, and discussions with their parents about peer relationship problems presented on videos. Raters coded the interaction live, with rating scales assessing parental warmth (warmth-coldness, pleasure-displeasure) and control (limit-setting and maturity demands), the two dimensions of Baumrind’s (1980) parenting style typology (authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, disengaged). ICCs of the parenting scales ranged from .71 to .89, with a median of .75.

Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory

We created the Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory (CABI), a reliable, valid measure of children’s school adjustment for teacher reports to measure children’s social-emotional behaviors in the classroom in terms of both competence and problematic behavior (P. A. Cowan et al., 2005). The CABI is comprised of 106 items from which we created 22 scales and reduced via a PCA to 6 overall composite measures of functioning, four of which were used in the present study: Externalizing-Aggressive, Externalizing-Hyperactive, Internalizing-Social Isolation, Internalizing-Anxious Depressed (see above cite for more details). Teachers completed the CABI for the study target children and their classmates in fall and spring of the year. Spring ratings were used in the present analysis based on the expectation that teachers would know the children more fully by springtime.

Growth Curve Methodology

The fact that there are 4 or 5 data points with identical measures from the same participants makes this study an ideal candidate for growth curve analysis (Singer & Willett 2005; Muthen & Muthen manual) through a latent variable framework, where model parameters are estimated by the method of maximum likelihood. We fit a linear random effects model given by the standard Level 1 and Level 2 equations (see below). Model fit was assessed by a host of indices, with χ2, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) chosen for reporting purposes. Level 1 is a within-subjects model, where the trajectory of each participant is distinguished based on individual growth parameters. Level 2 is a between-subjects model, where the individual growth parameters from Level 1 are the outcomes of interest predicted by the randomly assigned experimental condition.

For individual i (i=1,2,…,n) at time point t (t=1,2,…,T) the level-1 equation (within-person) is represented by:

| (1) |

where yit are outcome variables of interest (e.g., marital satisfaction, child adjustment) determined by the random effects η0i (growth intercept) and η1i (growth slope), and timescore (x=0,1,2,5,10). The level-1 residual term εit accounts for the difference between individuals’ true and observed trajectories. The level-2 equations (between-person) defining the random effects are given by:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where α0 and α1 are fixed intercepts, γA0, γA1, γB0, γB1, are fixed slopes, and wA and wB are two time-invariant covariates comprising the three intervention groups. Note that other covariates of interest can easily be added at level-2, by simply creating extra parameters in the model (e.g., child’s sex is considered in the analysis of child outcomes). The level-2 residual terms ζ0i and ζ1i account for the proportion of the individual growth parameters not explained by the covariates.

RESULTS

The analyses were conducted first using data from the 81 families constituting the efficacy trial—families who participated in the experimental conditions to which they were assigned. Analyses were then performed on data from the 100-family intention-to-treat sample, which included an additional 19 families who were assigned to one of the two intervention conditions, did not attend group meetings, but participated in more than half of the follow-up assessments.

There were 12 growth curves calculated for measures of: marital quality (his and her marital satisfaction, negative and positive couple communication), parenting style (his and hers), and children’s outcomes (boys’ and girls’ externalizing aggressive, externalizing hyperactive, internalizing shy/withdrawn, internalizing anxiety/depression). In order to conserve space we present the growth curve calculations but not the figures, which are available from the second author. Details of the level-1 and level-2 residual terms from analyses are available from the second author. Six of the 12 growth curves showed an adequate fit to the data along with statistically significant effects of the intervention: mothers’ and fathers’ marital satisfaction, positive and negative marital communication, and the two externalizing measures of children’s behavior in school. In addition to raw p-values, we report family-wide Bonferroni adjusted p-values to control the Type I error rate at the level of the mutually exclusive families of hypotheses (i.e. each growth curve model). We believe that it was a signal achievement to show 10-year intervention effects in 50% of the measures tested. Effect sizes for significant unadjusted treatment effects were calculated by Pearson correlation coefficients (Rosenthal, 1994), and defined as “small” (r=0.10), “medium” (r=0.30), or “large” (r=0.50) (Tables 1–3).

Table 1.

Predicting Marital Satisfaction over 10 years as a function of Time (at level-1) and Intervention Group (at level-2) for n=81 mothers and n=81 fathers separately.

| Mothers Marital Satisfaction ( , p = 0.81; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.00 [0.00, 0.07]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | ||||||

| Growth curve Slopes | Marital | 0.00 | ||||

| Parenting | −0.05 | |||||

| Control | −0.14 | |||||

| Fixed Effects | Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | |

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 7.11 | 0.26 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.99 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | −0.26 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.98 | |

| Slope, η1i | Intercept | α1 | −0.14 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control1 | γA1 | 0.14 | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Parenting vs. Control2 | γB1 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.36 | |

| Fathers Marital Satisfaction ( , p = 0.26; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.05 [0.00, 0.12]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | ||||||

| Growth curve slopes | Marital | −0.01 | ||||

| Parenting | −0.19 | |||||

| Control | −0.11 | |||||

| Fixed Effects | Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | |

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 6.84 | 0.25 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.37 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 0.99 | |

| Slope, η1i | Intercept | α1 | −0.11 | 0.03 | <0.01 | 0.09 |

| Marital vs. Control3 | γA1 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.15 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB1 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.45 | |

Effect size r=0.33;

Effect size r=0.21;

Effect size r=0.24

Note: Adjusted p-values determined by Bonferroni correction

Table 3.

Predicting Teacher-Rated Child Adjustment over 10 years as a function of Time (at level-1) and Intervention Group and Child’s Sex (at level-2) for n=81 children.

| Hyperactive Behaviors( , p = 0.29; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.05 [0.00, 0.13]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | ||||||

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| Growth curve slopes | Marital | −0.18 | −0.11 | |||

| Parenting | −0.05 | 0.02 | ||||

| Control | −0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| Fixed Effects | Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | |

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 1.18 | 0.38 | <0.01 | 0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.94 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | −0.23 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.99 | |

| Female | γC0 | −1.04 | 0.39 | <0.01 | 0.06 | |

| Slope, η1i | Intercept | α1 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.91 |

| Marital vs. Control1 | γA1 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.30 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB1 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 0.99 | |

| Female | γC1 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.78 | |

| Aggressive Behaviors ( , p = 0.28; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.05 [0.00, 0.13]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | ||||||

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| Growth curve slopes | Marital | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||

| Parenting | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||

| Control | 0.16 | 0.17 | ||||

| Fixed Effects | Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | |

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 4.87 | 0.46 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.34 | 0.96 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | −0.12 | 0.56 | 0.84 | 0.99 | |

| Female | γC0 | −0.56 | 0.47 | 0.23 | 0.88 | |

| Slope, η1i | Intercept | α1 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.72 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA1 | −0.24 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.47 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB1 | −0.11 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 0.99 | |

| Female | γC1 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.99 | |

Effect size r=0.22;

Note: Adjusted p-values determined by Bonferroni correction

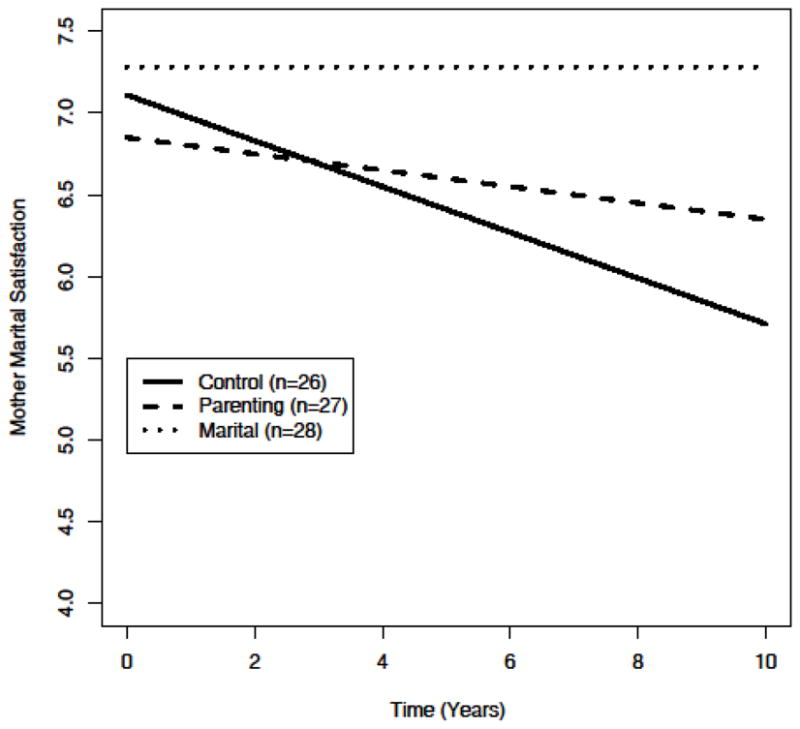

Marital Satisfaction

To investigate the effect of treatment group within this efficacy trial, growth curve models were fitted separately for mothers and fathers, each summarized in Table 1. Employing a latent variable approach, model fit was assessed by a Chi-Square statistic (low values provide evidence for better fit), CFI (values should be 0.90 or higher), and RMSEA (values should be <0.05). Both mothers’ ( , p = 0.81; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.00 (0.00 – 0.07)) and fathers’ ( , p =0.26; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.00–0.12)) growth curve models were found to have convergent evidence of good model fit (Table 1).

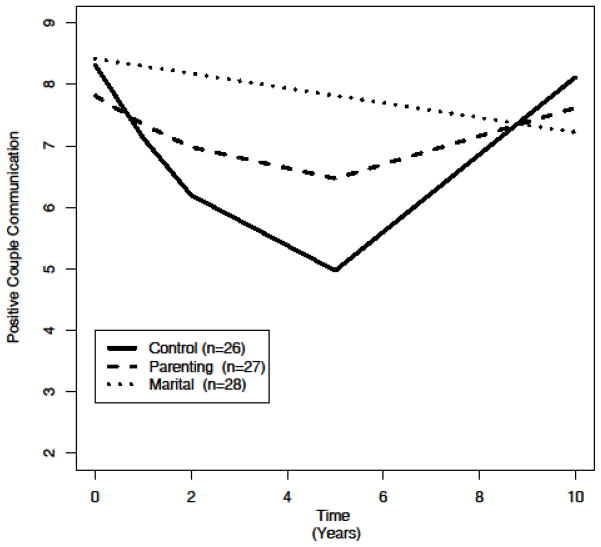

The fixed effect parameters γA0 and γB0 were not statistically significant (Table 1) for mothers or fathers. Mothers and fathers in all three conditions began on average at roughly the same level of initial marital satisfaction at baseline. Over time, there was virtually no change over 10 years in the marital satisfaction of the parents in the marital emphasis groups (Mothers Δ =0.00; Fathers Δ =−0.01), whereas participants in both the parenting emphasis groups (Mothers Δ =−0.05 Fathers Δ=−0.19) and the control group (Mothers Δ=−0.14;Fathers Δ =−0.11) showed some decline in marital satisfaction. We tested the significance of the differences between each type of couples group and the controls. The slope parameter comparing change over time in the marital emphasis group and the control group was statistically significant (Mothers γA1 = 0.14, p < 0.01, pAdj = 0.03; Fathers γA1 = 0.10, p = .01, pAdj =0.15). Specifically, mothers and fathers in the marital-focus group were more likely to maintain their marital satisfaction over 10 years as compared with controls. Participation in the parenting-focus group produced a marginal advantage for mothers but none for fathers. Effect sizes ranged from small to medium. For reasons of space, only mothers’ growth curves are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Growth curves for mothers marital satisfaction

Couple Communication

Growth curve models were fitted for couple communication quality as observed by two raters -- as the parents worked on a marital and parenting problem without their child present, and as they worked with their oldest child on challenging tasks at each follow-up over the school years. Results of growth curves for both positive and negative couple communication are summarized in Table 2. In both instances a quadratic model was fit to the data.

Table 2.

Predicting Couple Communication over 10 years as a function of Time (at level-1) and Intervention Group (at level-2) for n=81 mother/fathers dyads.

| Positive Couple Communication ( , p = 0.53; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.00 [0.00, 0.13]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 8.32 | 0.56 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | 0.10 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 0.99 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | −0.50 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.99 | |

| Linear, η1i | Intercept | α1 | −1.32 | 0.29 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control1 | γA1 | 1.20 | 0.38 | <0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Parenting vs. Control2 | γB1 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.33 | |

| Quadratic, η2i | Intercept | α2 | 0.13 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control3 | γA2 | −0.13 | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Parenting vs. Control4 | γB2 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.27 | |

| Negative Couple Communication ( , p = 0.24; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.06 [0.00, 0.15]) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | p | Adj p | ||

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept, η0i | Intercept | α0 | 6.76 | 0.72 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Marital vs. Control | γA0 | −0.44 | 0.99 | 0.66 | 0.99 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB0 | 090 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 0.98 | |

| Linear, η1i | Intercept | α1 | 0.41 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.99 |

| Marital vs. Control5 | γA1 | −1.40 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.19 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB1 | −1.06 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 0.58 | |

| Quadratic, η2i | Intercept | α2 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.99 |

| Marital vs. Control6 | γA2 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.13 | |

| Parenting vs. Control | γB2 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.65 | |

Effect size r=0.33;

Effect size r=0.22;

Effect size r=0.35;

Effect size r=0.23;

Effect size r=0.25;

Effect size r=0.26

Note: Adjusted p-values determined by Bonferroni correction

Examining the model describing change in positive and negative couple communication across time, we found no evidence to reject the null hypothesis of good model fit. For Positive couple communication the fit indices were: , p = 0.53; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.00 (0.00 – 0.13); and for Negative couple communication: , p = 0.24; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.06 (0.00 – 0.15)). There was no evidence that initial Positive communication status was associated with treatment status, i.e. the fixed effects γA0 and γB0 were both statistically non-significant. However, there was evidence of treatment group differences in rate of change and rate of acceleration for Positive couple communication, with different effects for Positive and Negative couple communication. From pretest to 4th grade, couples in the marital-emphasis groups improved markedly in their communication quality, with declining negative and increasing positive communication in their problem-solving discussions and co-parenting interactions. Couples in the parenting-emphasis groups showed no change. Control couples showed a decline in couple communication quality, with a curve in mirror image of the couples group participants --increasing negative and decreasing positive scores according to the observers. However, 5 years later, when their children entered high school, there were no differences among the three conditions, as at the beginning of the study.

We tested for the significance of the differences between slopes (Table 2). The fixed effects describing the difference between the rate of change in Positive couple communication of parents in the marital-focus and control groups (γA1 = 1.20, p < 0.01, pAdj=0.02) were statistically significant and the parenting-focus and control group differences (γB1 = 0.80, p = 0.04, pAdj=0.33) were marginally statistically significant. Similarly, the acceleration (or deceleration) of growth fixed effects were significant for the parameters comparing marital-emphasis groups versus control (γA2 = −0.13, p < 0.01, pAdj=0.01) and marginally significant for parenting-emphasis groups versus control (γB2 = 0.08, p = 0.03, pAdj=0.27). Couples in the control group declined significantly in Positive communication more rapidly than those in the ongoing marital-focus and parenting-focus groups, although they rebounded at the final assessment point when their first child, now adolescent, had entered high school. There was a marginally significant difference between marital-focus and control group in rate of change (γA1 = −1.40, p =0.02, pAdj=0.19) and rate of acceleration (γA2 =0.15, p = 0.02, pAdj=0.13) of growth with regard to Negative communication. The controls increased in negative communication and then later declined, whereas the marital-emphasis group declined sharply only to increase again between the 4th and 9th grade assessments. Only the positive communication growth curves are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Growth curves for positive couple satisfaction

Parenting Style

We attempted to construct growth curve models for fathers’ warmth and structure when they worked and played separately with their child. In neither case did the model fit the data, so we could not go on to the second step of testing for intervention effects. Similar results were obtained for mothers’ structuring of the tasks. The model for mothers’ warmth did fit the data, but no significant intervention effects were found.

Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory

Teacher ratings of child behaviors over the school years were also modeled as growth curves, which included the addition of child sex as a covariate, hypothesized as a potentially meaningful main effect in addition to intervention status. Teacher ratings of both hyperactive and aggressive behaviors collected in the spring of Kindergarten, 1st, 4th, and 9th grades were used in the growth curve analyses, summarized in Table 3.

The models for hyperactivity and aggressive behavior change over time were found to have appropriate model fit, (Hyperactivity, , p = 0.29; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.00 – 0.13); Aggression , p = 0.28; CFI = 0.94; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.00 – 0.13). In examination of the effects of the covariates of interest on initial status of the child’s hyperactivity (teacher-rated), there was no association found with treatment status (i.e. γA0 and γB0 were both statistically non-significant). There is evidence that boys started with elevated levels of hyperactivity compared to girls (γC0 = −1.04, p = 0.008), but there were no sex differences in initial level of aggressive behavior.

There were treatment group differences in rate of change for children’s hyperactivity over the school years, with behavior problems increasing for both male and female children whose parents were in the control condition, and decreasing for children whose parents were in the marital-emphasis groups (See Table 3 for slopes). There was a marginally statistically significant difference between the rate of change in children whose parents were in the marital-focus and control groups (γA1 = −0.12, p = 0.05, pAdj=0.30). Children of parents in the marital-focus intervention experienced a sharper decline in hyperactivity as compared to children whose parents were randomly assigned the control condition. Child’s sex was not associated with differences in the rate of change of hyperactivity over time, i.e. γC1 was non-significant.

There is marginal evidence of a trend in treatment group differences in rate of change of aggression, though it is not significant at the α=0.05 level, i.e. γA1 = −0.24, p < 0.08, pAdj=0.47. This trend reveals that children whose parents were in the group with a marital focus had, on average, a declining aggression trajectory, whereas children with parents in the control condition displayed, on average, increasing aggressive behaviors over the school years from kindergarten to 9th grade.

We found that a model summarizing the trajectory of anxiety/depression fit the data well, but there were no significant intervention effects detected. The model for social isolation did not fit the data, and higher order equations did not converge.

Intention-to-Treat Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed to help rule out the possibility that participant dropouts altered the effects of randomization and inflated Type I error rates. Growth curve models were parallel to the results above from the efficacy subset analysis: the intention-to-treat analyses were performed with the 100 participant families (i.e. 41 marital, 33 parenting, 26 control) based on the initial randomized treatment condition they were assigned at study entry.

Intention-to-treat analysis of mothers’ and fathers’ marital satisfaction growth curves were performed, with both models displaying acceptable model fit (i.e. , p = 0.87; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.00 (0.00 – 0.05) and , p = 0.17; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.06 (0.00 – 0.12), respectively). Results were highly similar to those from the efficacy subset analysis displayed in Table 1. For mothers, the slope parameter comparing change over time in the marital-focus groups to that of the control group was statistically significant (γA1 = 0.11, p < 0.01, pAdj=0.03), while the slope parameter comparing mothers in the parenting-focus groups and the control group was marginally significant (γB1 =0.09, p = 0.04, pAdj=0.33). Similarly, for fathers the slope parameter comparing change over time in the marital-focus groups and the control group was marginally significant (γA1 = 0.08, p = 0.046, pAdj=0.35), as was the slope parameter comparing fathers in the parenting-focus groups and the control group (γB1 = 0.08, p = 0.07, pAdj=0.39). Couple Communication results for the intention-to-treat sample again yielded highly similar results to the efficacy subset analysis summarized in Table 2. For observed positive couple communication, growth curve model fit was good ( , p = 0.42; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.01 (0.00 – 0.13)) and intervention effects on the rate of change and rate of acceleration over time were significant when comparing couples in the marital-focus groups to the control group (i.e. γA1 =1.22, p<0.01, pAdj=0.02 and γA2=−0.13, p<0.01, pAdj=0.01, respectively) with a comparable interpretation as before. Comparing the parenting-focus and control groups, we found that rate of change and rate of acceleration in the intention-to-treat sample did not yield statistically significant results as it did in the efficacy subset analysis (i.e. (γB1 =0.68, p=0.09, pAdj=0.58 and γB2=−0.07, p=0.06, pAdj=0.52, respectively). Negative couple communication observations were also modeled in parallel to the results above, with appropriate model fit ( , p = 0.17; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.76 (0.00 – 0.15)) and comparable intervention effects as observed within the efficacy subset, namely that intervention effects on the rate of change (γA1 =−1.36, p=0.02, pAdj=0.19) and rate of acceleration (γA2 =0.14, p=0.01, pAdj=0.09) over time were significant comparing the marital-focus groups with the control groups.

Finally, teacher-rated externalizing behaviors were modeled with the n=100 intent-to-treat sample, with intervention effects becoming much weaker than those reported in the efficacy subset trial. Model fit was deemed acceptable for growth curve models for hyperactive and aggressive behaviors (i.e. , p = 0.19; CFI =0.92; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.06 (0.00 – 0.13) and , p =0.25; CFI =0.95; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.05 (0.00 – 0.12), respectively) but no statistically significant intervention effects were found.

DISCUSSION

One unique feature of this study was the 10-year post-intervention follow-up. In different domains using different measures and data sources, we found positive, long-lasting effects of a preschool intervention on the family and on the child making the transition to high school. Intervention effects were subjected to increasingly conservative statistical comparisons of marital vs control and parenting vs control changes over time – raw p-values, Bonferonni-adjusted p-values, and intention-to-treat analyses. The least conservative raw p-values showed statistically significant effects in favor of the marital-focus groups for mothers’ and fathers’ marital satisfaction, positive and negative couple communication, and children’s hyperactivity. After correcting for multiple comparisons, and using the intention-to-treat sample, mothers’ marital satisfaction and the couple’s positive communication still showed 10 year effects of participating in groups that emphasized issues in the relationship between the parents. The least conservative statistical tests showed significant effects of participating in a parenting-focused group on mothers’ marital satisfaction, and positive couple communication, although the differences between parenting-focused and low-dose control participants were no longer deemed statistically significant after Bonferonni corrections and analyses of the intention-to-treat sample.

The intent-to-treat analyses revealed similar trends but weaker findings, as expected. These results were obtained despite the fact that 27% of the couples assigned to the intervention conditions did not attend one couples group meeting. In adolescence, children of parents who did attend the groups as couples reaped significant benefits 10 years after the intervention.

We note that the Bonferroni corrections are meant to guard against concluding that the interventions have an effect when they do not. But there is also a risk of concluding that these interventions are ineffective when they actually produce positive changes or prevent negative changes in the participants. Clearly the intervention effects we are describing here are not large, and there is variability within groups, but the findings are noteworthy in that very similar patterns of effects are found over a ten year period with data drawn from independent sources – fathers’ and mothers’ self-reports, different sets of observers’ ratings of marital interaction, and different teachers’ descriptions of the child/adolescent in the classroom.

Quadratic change trajectories in observed positive and negative couple communication during a problem-solving discussion revealed significant advantages for parents in the marital-focus intervention over a period of 6 years. From kindergarten to 4th grade, children whose parents participated in the marital-focus or parenting-focus couples groups presumably grew up in an environment in which their parents were increasingly positive and decreasingly negative in their communication as a couple. Things changed for the parents as the children entered high school. The earlier positive intervention effects on how parents attempted to resolve their disagreements disappeared, so that parents from the marital-focus groups no longer held their communication advantages and the control couples were no longer at a disadvantage. We can conclude that satisfaction with the relationship was maintained for the marital-focus group participants despite the fact that couple communication became more negative and less positive somewhere between the 4th grade year and their child’s entrance to high school. The intervention also had long-lasting effects on the adolescents’ externalizing behaviors (less hyperactivity and aggression) according to their teachers, but not on internalizing behaviors such as social withdrawal and depression.

A second unique feature of this study was the examination of intervention effects over two major transitions in a child’s life – beginning elementary school and entering high school. It has been assumed that enhancing children’s and parents’ abilities to cope with earlier transitions would have payoff for transitions experienced later on, but as far as we are aware this assumption has never been examined with a randomized clinical trial intervention design.

In earlier published results of this study from preschool to 1st grade, there were stronger effects on the couple (maintaining marital quality, improving parenting effectiveness) of couples groups focused more on marital issues than of groups focused more on parenting issues (improving parenting effectiveness). The present results suggest that the advantages of parents participating in groups with an emphasis on couple relationship issues persisted over time.

Limitations

The conclusions that we draw from the study results must be considered in light of its limitations. Although each of the families was examined in intensive detail, which required extensive involvement of different assessment teams over the years, only 81 families participated in the randomized design so the power to detect intervention effects was relatively low. The fact that significant effects were found in the main outcome variables is noteworthy. Furthermore, the participants could be described as being at relatively low risk by virtue of their incomes and marital status. Only replication with more participants in a more diverse sample can adequately test how widely we can generalize from the present results.

Although we have evaluated two intervention conditions in the current study (marital-and parenting-focused) in contrast with a control condition, there are other intervention variations to be tested. Would lower dosage interventions with fewer group meetings have been less successful? Would higher dosage interventions have produced stronger results? We believe that the group format has significant power to reduce stress and produce change, but we have not evaluated whether group versus couple-by-couple interventions might have different effects. Finally, whereas almost all interventions directed to cushioning potential negative effects of school transitions have been based within the school, the intervention described here was couple-based. It is possible that an approach that combined a school and family approach would have additive or even synergistic effects.

Although there are many advantages of precision to be gained by growth curve analysis, in creating trajectories for each participant, there must be overall growth trends across time before intervention effects can be ascertained. In fact, except for measures of mothers’ warmth toward the child, the models for mothers’ structure and fathers’ warmth and structure did not fit the data, so intervention effects on parent-child interaction could not be tested. In contrast to the couple interaction task, which was identical at each time period, the parent-child tasks were adapted to make them more appropriate to the child’s developmental level. The methodological shifts necessitated by finding age-appropriate parent-child interactions may have interfered with the measurement of growth curves over time.

Unlike the pattern of intervention effects found for kindergarten and 1st grade children, the present analyses did not reveal any longer-term effects of the intervention on our measures of child-to-adolescent internalizing behavior. It could be that high school teachers who saw adolescents in their classes only one period a day were not as sensitive to social withdrawal, anxiety, or depression as they were to acting out, aggressive behavior or hyperactivity. It is also possible that long-term effects of the early interventions on depression might not show up until later in adolescence (16–17) when the incidence of internalizing disorders typically begins to rise.

The design of this study does not permit a statistical analysis of the processes by which the interventions produced their effects. Here we provide some speculations based on our clinical experiences with observing the groups and reading post-intervention interviews with the participants. The most salient effect of the intervention, in our view, lies in the power of the group to normalize what happens to families as parents of young children attempt to juggle the often conflicting needs and demands arising from jobs, personal struggles, and couple communication failures, and deal with both the joys and the frustrations of caring for children. Sharing the experiences of others facing similar challenges helps to reduce expectations for self and partner to more realistic levels, while providing social support and hope. The opportunity for mothers and fathers to discuss issues and differences in a safe setting leads to new solutions to old problems, and to increased ability to regulate their individual negative emotions and their interactions with each other and their child. Over the course of 16 weeks, participants learn how the five aspects of life they discuss are interrelated -- for example, how intergenerational and personal issues affect the strategies they use to resolve differences when they are upset.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings reported here show that 32 hours of participation in a couples group before the first child makes the transition to elementary school can have benefits for both the couple and the child over a period of 10 years from kindergarten to high school. Although we have not yet been able to determine the relative ratio of costs and benefits, we speculate that increasing students’ task focus and reducing hyperactivity and aggression at the high school level will produce cost savings that far exceed the costs for earlier preventive intervention.

This project began in a context in which the few evaluated interventions to facilitate children’s coping with major school transitions were based in schools. Without denying the utility of school-based efforts to ease the transition to elementary or high school, data from the present study suggest that early family-based interventions can help children negotiate the social and academic challenge of entering complex new educational institutions.

The project also began in a context in which government funding and most classes or social services to enhance the relationship between parents and children focus on parenting skills. The present study suggests that at least some focus on mothers and fathers, and on the relationship between them as a couple and as co-parents might serve to make parenting interventions more effective by helping reduce the potential spillover of their distress in ways that affect the quality of their relationships with their children.

Footnotes

This project was supported over its ten-year span by the National Institute of Mental Health, MH-31109. The authors wish to thank the leaders of the couples groups: Susan Brand, Ben Kanne, Gary Whitmer, Deborah Rafael, Paul Guillory, Donna Guillory, Michelle Holt, and Michael Haas. We also thank the many undergraduate and graduate students who worked on the project and the families who shared their lives with us over the years.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/fam

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Dauber SL. First-grade classroom behavior: Its short- and long-term consequences for school performance. Child Development. 1993;64(3):801–814. doi: 10.2307/1131219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. New directions in socialization research. American Psychologist. 1980;35(7):639–652. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.35.7.639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J. The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior. In: Collins WA, editor. Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol. 13. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: the big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Ablow JC, Johnson VK, Measelle JR. The family context of parenting in children’s adaptation to elementary school. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Heming G. Unpublished manuscript. University of California; Berkeley: 1995. Manual for the Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory (CABI) [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS. Marital Discord and Children’s Emotional Self-Regulation Snyder. In: Douglas K, Simpson Jeffry, Hughes Jan N, editors. Emotion regulation in couples and families: Pathways to dysfunction and health. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 163–182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Aitken JJ, Shelton KH. Inter-parental conflict and children’s academic attainment: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(12):1223–1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Assessing young children’s views of their academic, social, and emotional lives: An evaluation of the self-perception scales of the Berkeley Puppet Interview. Child Development. 1998;69(6):1556–1576. doi:10.1111.j.1467-8624.1998.tb060177.k. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fathers and families. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 27–73. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Rimm-Kaufman SE, Cox MJ. Introduction: An ecological approach to kindergarten transition. In: Pianta RC, Cox MJ, editors. The transition to kindergarten. Baltimore: P.H. Brookes; 1999. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schulting AB, Malone PS, Dodge KA. The effect of school-based transition policies and practices on child academic outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(6):860–871. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MS, Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Promoting healthy beginnings: A randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention to preserve marital quality during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(1):20–31. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Aber JL, Allen L, French SE. The impact of the transition to high school on the self-esteem and perceived social context of poor urban youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(4):489–515. doi: 10.1007/BF02506794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]