Abstract

In the context of OA disease, NF-κB transcription factors can be triggered by a host of stress-related stimuli including pro-inflammatory cytokines, excessive mechanical stress and ECM degradation products. Activated NF-κB regulates the expression of many cytokines and chemokines, adhesion molecules, inflammatory mediators, and several matrix degrading enzymes. NF-κB also influences the regulated accumulation and remodeling of ECM proteins and has indirect positive effects on downstream regulators of terminal chondrocyte differentiation (including β-catenin and Runx2). Although driven partly by pro-inflammatory and stress-related factors, OA pathogenesis also involves a “loss of maturational arrest” that inappropriately pushes chondrocytes towards a more differentiated, hypertrophic-like state. Growing evidence points to NF-κB signaling as not only playing a central role in the pro-inflammatory stress-related responses of chondrocytes to extra- and intra-cellular insults, but also in the control of their differentiation program. Thus unlike other signaling pathways the NF-κB activating kinases are potential therapeutic OA targets for multiple reasons. Targeted strategies to prevent unwanted NF-κB activation in this context, which do not cause side effects on other proteins or signaling pathways, need to be focused on the use of highly specific drug modalities, siRNAs or other biological inhibitors that are targeted to the activating NF-κB kinases IKKα or IKKβ or specific activating canonical NF-κB subunits. However, work remains in its infancy to evaluate the effects of efficacious, targeted NF-κB inhibitors in animal models of OA disease in vivo and to also target these strategies only to affected cartilage and joints to avoid other undesirable systemic effects.

Keywords: Cartilage, chondrocytes, homeostasis, hypertrophy, inflammation, osteoarthritis, NF-κB, IKKs

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis, the rheumatic disease with the highest prevalence and economic impact, is a degenerative malady driven, in part, by signaling mechanisms induced by stress- and inflammation-induced factors [1-5]. These factors activate normally quiescent chondrocytes, the unique cell component in cartilage, which are then no longer able to maintain tissue homeostasis [6]. In cartilage development and at the post-natal growth plate, chondrocytes undergo terminal differentiation and hypertrophy [1,7,8] with various signaling pathways and transcription factors playing stage-specific roles in chondrogenesis [7,9]. Endochondral ossification is the final outcome of the “chondrogenic program”, which begins with chondroprogenitor proliferation from mesenchymal stem cells and ends in cartilage matrix calcification [7]. During the course of hypertrophy, due to exacerbated environmental stress associated with ECM remodeling, chondrocytes also succumb to programmed cell death {PCD/apoptosis} [7]. Indeed, the de-regulated/disorganized chondrocyte differentiation observed in OA cartlage has been proposed as a “developmental model” for OA pathogenesis [5,10]. This is because many of the alterations observed in OA diseased cells appear to mimic or re-capitulate the pattern of chondrocyte differentiation in fetal skeletogenesis including ECM remodeling, matrix calcification, apoptosis and proliferation [10]. It is essential in this context to always bear in mind that the degenerative, uncoordinated events associated with OA disease should not be equated with highly regulated developmental programming [5]. However the co-opting of components and reaction parameters of normal chondrocyte differentiation in OA disease may provide important, telling insights into its causes and possible therapy.

Alterations in ECM structural integrity or in effectors of progression to hypertrophy can lead to OA pathology [11] and this has been illustrated in murine models of OA disease. The importance of the fine protein network and stability of the ECM in joint mechanical flexibility and cartilage health with age is well documented in studies of cho/+ (Col11a1-haploinsufficient), Col9a1−/− (type IX collagen-deficient) and Timp3−/− mice, which present age-dependent cartilage degeneration similar to that of OA patients [12-14]. Careful analysis of the articular chondrocytes of cho/+ mice revealed that the OA pathology is associated with up-regulation of discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), (a receptor for native type II collagen), which enhances MMP-13 expression in regions where the collagen network has been denuded of proteoglycans [15,16]. DDR2 and MMP-13 up-regulation were also associated with the extent of cartilage damage in human knee joints [17]. Importantly, surgically induced OA disease models in mutant mice have also implicated aggrecanase-2/ADAMTS5 [18], DDR2 [16], Runx2 [19] and, more recently, MMP-13 [20] as endogenous effectors/mediators linked to the onset and/or severity of OA joint disease [21]. In addition, the enforced activation of β-catenin signaling in the articular chondrocytes of adult mice was recently been shown to lead to premature chondrocyte differentiation and the development of an OA-like phenotype [22]

This review will focus on the NF-κB signaling pathways in OA disease: (1) how elevated canonical NF-κB signaling in OA chondrocytes contributes to cartilage degeneration in OA by affecting a number of downstream processes (particularly in response to extrinsic stress and inflammatory signals), (2) how NF-κB signaling may contribute to hypertrophic-like differentiation of chondrocytes in OA and (3) how up-todate strategies for inhibiting NF-κB and the IKK complex may be considered for therapy of OA.

NF-κ Bs and their signaling complexes

Members of the NF-κB transcription factor family orchestrate a wide range of stress-like inflammatory responses, regulate developmental programs and cellular differentiation and control the growth and survival of normal and malignant cells [23-26]. Selectivity as well as redundancy in NF-κB mediated transcriptional control arises from the assembly of homodimers and heterodimers of 5 different NF-κB proteins (RelA/p65, RelB, c-Rel, NFκB1/p105 and NFκB2/p100). NF-κB dimers are sequestered in the cytoplasm and their transcriptional activities blocked by one of three small inhibitory NF-κB proteins (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε) or the larger precursor proteins p105 (NFκB1) and p100 (NFκB2). Finally, Bcl-3 and IκBζ are atypical IκB-like proteins, reported to have both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on specific NF-κB subunits or target genes, and are associated with DNA bound p50 homodimers and p50/p52 heterodimers. Like RelA/p65, RelB and c-Rel, Bcl-3 also has a transcriptional activation domain (reviewed in [26]). Proteins p100 and p105 are precursors of the mature DNA binding NF-κB p52 and p50 subunits, respectively and also function in their unprocessed forms as NF-κB inhibitors via their carboxy-terminal IκB-like domains (referred to as IκBδ and IκBγ proteins, respectively). Recent biochemical experiments have revealed that preformed NF-κB subunits interact with p105 (also called IκBγ in its IκB inhibitory mode) and p100 (IκBδ) in two ways [25,27]: (1) by direct binding of the Rel homology domains (RHDs) of p105 and p100 to the RHDs of preformed NF-κB partner proteins and (2) by the carboxy-proximal IκB ankyrin (ANK) repeat domains of p100 and p105 binding to preformed NF-κB dimers. Although the three small inhibitory IκB proteins would appear to have analogous functions, they have been found to act in temporally distinctive ways depending on their degradation and resynthesis [28]. Moreover, findings with cells lacking each of the three IκBα proteins indicate that their mechanisms of action are only partly due to NF-κB cytoplasmic sequestration as opposed to inhibiting NF-κB transcriptional activity [29]. In the cytoplasm, the classic, (so called canonical), NF-κB signaling module immediately reacts to almost all pro-inflammatory and stress-like responses. Canonical NF-κB heterodimers are activated by the site specific amino-terminal phosphorylation of IκBα by the IKK (inhibitor of NF-κB kinase) signalosome complex that targets it for ubiquitination and subsequent proteosomal destruction, thus resulting in the nuclear translocation of activated NF-κB heterodimers (predominantly p65/RelA-p50) and the activation of their specific target genes. The NF-κB p50 precursor protein, p105, is constitutively processed by the 20S proteosome and is also subject to IKK inducible processing, which is ubiquitination independent [30].

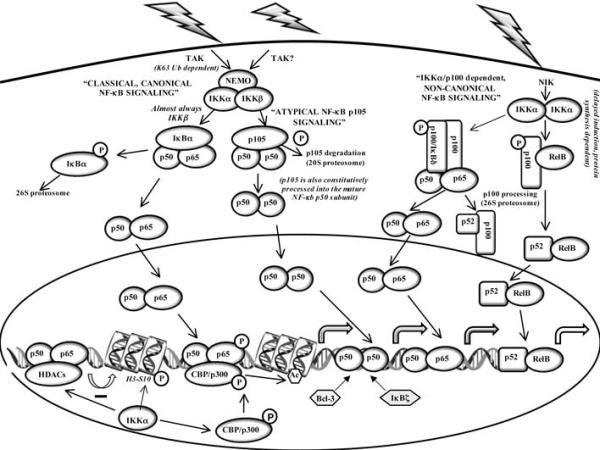

The IKK complex consists of two serine-threonine kinases, IKKα and IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ, a regulatory or docking protein that facilitates IKK complex assembly and regulates the transmission of upstream activating signals to IKKα and IKKβ [26,31,32]. Figure (1) depicts the different types or classes of IKK-driven NF-κB signaling pathways in cells. IKKβ is almost always the IκBα kinase that activates NF-κB-dependent immediate stress-like responses in vivo, although IKKα can also takes on this role in response to specific signaling pathways [33] and the latter also occurs, at least to some degree, under conditions of IKKβ inhibition [34]. Moreover, in contrast to the positive pro-inflammatory IKKβ, IKKα□ has been suggested to attenuate or resolve acute inflammatory responses by more than one mechanism [35-37].

Figure 1. Transcriptional regulation by NF-κB and components of the IKK signalosome complex.

Examples of the major IKK-driven NF-κB signaling pathways are illustrated. To simplify the figure, some additional high molecular weight complexes containing p105 (IκBγ) and p100 (IκBδ) and other preformed NF-κB subunits as well as other NF-κB complexes containing IκBβ and IκBε are not shown. In addition, NF-κB independent targets of IKKα acting as a nucleosomal kinase and the action of atypical IκB proteins Bcl-3 and IκBζ, which can have positive or negative effects on the transcription of specific NF-κB target genes, are indicated (see text for more detailed descriptions).

IKKα, not IKKβ, is specifically required for the activation of the so-called non-canonical or alternate NF-κB pathway [24,26,38]. In response to several specific extracellular inducers (including LTβ, CD40L and BAFF), NIK (NF-κB inducing kinase) activates IKKα, which targets p100/NFκB2 for site specific phosphorylation, flagging it for ubiquitination and subsequent proteosomal processing. When first described this IKKα dependent pathway was solely believed to liberate RelB/p52 NF-κB heterodimers, whose target genes regulate various stages of adaptive immunity, cellular survival, and differentiation programs [24,38] {see Fig. (1)}. However, p100 homodimers (acting as IκBδ modules) were recently shown to restrain RelA/p50 and RelB/p50 heterodimers in large ternary complexes [25]. In these ternary complexes one of the two IκBδ domains is believed to inhibit the Rel DNA binding domain of the p52 homodimer in the complex, while the second IκBδ domain acts in trans to inhibit the RelA/p50 or RelB/p50 heterodimer {as shown for the p100:p100/RelA-p50 ternary complex in Fig. (1)}. Similar high-molecular-weight, inhibitory NF-κB complexes were also recently identified for p105 (IκBγ) together with other preformed NF-κB subunits [27]. Interestingly, in response to NIK/IKKα-dependent non-canonical stimuli, the RelA/p50 heterodimers liberated by p100/IκBδ complexes could then activate some of the same genes as the canonical pathway but in a delayed manner. Thus as a direct target of the canonical pathway, p100 could integrate canonical and non-canonical signals resulting in functional cross-talk between pro-inflammatory/stress-like responses and developmental stimuli [25]. Moreover, in the absence of a non-canonical stimulus, p100, which is also far more stable than IκBα, could then act as a constitutive, negative feedback modulator that attenuates or limits persistent, pathogenic canonical NF-κB stimuli mediated by TLRs [39]. Finally, extracellular stimuli resulting in cellular responses that probably require sustained or long-lasting NF-κB induction activate canonical and non-canonical NF-κB heterodimers by eliciting IκBα degradation and p100 processing; and some specific signals also coordinate the deployment of both NF-κB activation pathways at the level of p100 processing [25,40-43].

Functions of IKKα independent of NF-κB signaling

IKK□ has a number of in vivo functions as a serine threonine kinase acting outside the NF-κB pathway {reviewed in [32,44]}. In established fibroblastic cells, IKK□ functions as a nucleosomal kinase that enhances the transcription of NF-κB target genes {reviewed in [44]}.Independent of the NF-κB signaling, IKKα also regulates effectors of the cell cycle, apoptosis, determinants of the DNA damage response and the expression of specific tumor suppressors [44-47].

In murine embryonic development, IKKα is essential for keratinocyte differentiation [48-50], but independent of NF-κB activation and its kinase activity [51]. Loss of IKKα is perinatally lethal probably due to the absence of a functional stratum corneum in IKKα knockout (KO) mice, thereby leaving the internal organs unprotected from the external environment [48]. Due to a total block in keratinocyte differentiation to produce a cornified layer, IKKα KO mice present a bottle-shaped body morphology with limbs and tails wrapped in a thick, sticky epidermal tissue preventing their extension from the body trunk [48]. IKKα KO mice do not have major changes in the pattern and size of proximal limb elements and have normal numbers of lumbar and thoracic vertebrae with overall skeletal development and cartilage formation intact. However, IKKα KO embryos exhibit a number of specific developmental abnormalities including: abnormal curvature of the distal limb elements; deformed phalanges; a cleft secondary palate and deformed incisors; bifurcated xiphoid process; split sternebra 6; and shorter and kinked, though functional, sternal bands, probably due to incomplete and asymmetric ossification [48-50]. IKKαAA/AA knock-in mice, in which alanines replace Ser176 and Ser180 T loop activating phosphorylation sites, are morphologically normal and fertile [52,53]. Thus, in conjunction with the fact that p52/p100 KO mice have no embryonic defect [54,55], the IKKα-dependent, non-canonical NF-κB pathway is not required for normal mouse development.

Subsequent work revealed that the abnormal skeletal development of IKKα KO mice was due to failed epidermal differentiation, which disrupted normal epidermal-mesodermal interactions [56]. Even though normal skeletal development was restored in IKKα−/− mice by rescuing IKKα expression only in the epidermis (CK14-Ikkα mice), the newborn mice died 2 days after birth from a suckling defect due to a fused esophagus, which was caused by the lack of expression of the basal keratinocyte-specific CK14-Ikkα transgene in that particular stratified epithelial tissue [56]. Abnormally high levels of specific FGFs (including FGFs 8 and 18), which accumulate in IKKα KO mice, were the cause for the skeletal abnormalities [56], probably due to collateral effects of specific FGFs on BMP signaling leading to localized alterations in chondrogenesis or ossification [56-60]. Thus taken together, these published findings have ruled out an essential role for IKKα in chondrogenesis during development. However, since CK14-Ikkα mice die several days after birth [56], it remains unknown if IKKα influences articular chondrocyte homeostasis in the joints of normal adult mice or their progression to hypertrophy at the post-natal growth plate and, more specifically, if the presence or absence of IKKα protein in adult articular chondrocytes affects the onset or course of OA disease.

NF-κB canonical signaling in OA disease

Although chondrocytes are quiescent in normal cartilage, they may be activated by inflammatory mediators, mechanical stress, matrix degradation products, and age-related advanced glycation end products (AGEs), leading to a phenotypic shift and to the aberrant expression of inflammation-related genes that cause the imbalance between catabolic and anabolic responses characteristic of OA chondrocytes [61]. Aging is one of the risk factors, if not the major one, that determine OA development, since the aged or senescent chondrocytes show a differential activity when compared to healthy, or normal cells [62]. The characteristic features of aging chondrocytes include epigenetic modulations that lead to de-regulated gene expression, exacerbated and sustained NF-κB activation and MMP production after IL-1 stimulation [63-65], and also increased accumulation and expression of both AGEs and the AGE receptor, RAGE [66-68]. Indeed, RAGE signals through the canonical NF-κB pathway to trigger the expression of metalloproteinases (MMPs), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), nitric oxide (NO), and type X collagen [69-72] in chondrocytes, leading to increased cartilage degradation and chondrocyte hypertrophy in OA cartilage. In addition, pro-inflammatory factors produced directly by the OA chondrocytes and other joint tissues contribute to the exacerbation of the cartilage erosion and loss of function. Among those pro-inflammatory factors, interkeukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor (IL-1β and TNFα) play major roles in cartilage degradation by evoking a cascade of events leading to both increased catabolism and chondrocyte hypertrophy [61,73,74]. More recently, different reports have shown a link between the activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and disease in OA cartilage [75]. Indeed, chondrocytes express TLRs 1-9 [76], but predominantly TLR2 [77], with increased levels in OA cartilage compared to normal cartilage and up-regulation by IL-1β and fibronectin [77,78], accounting for a positive feedback pro-inflammatory loop that promotes cartilage catabolism. Other reports indicate that the levels of both TLR2 and TLR4 are up-regulated in OA cartilage lesional areas [78] and that stimulation of chondrocytes with peptidoglycan and LPS, ligands of TLR-2 and 4, respectively, increases the expression of MMP-1, 3, and 13, as well as NO production, in a manner dependent on NF-κB [78,79].

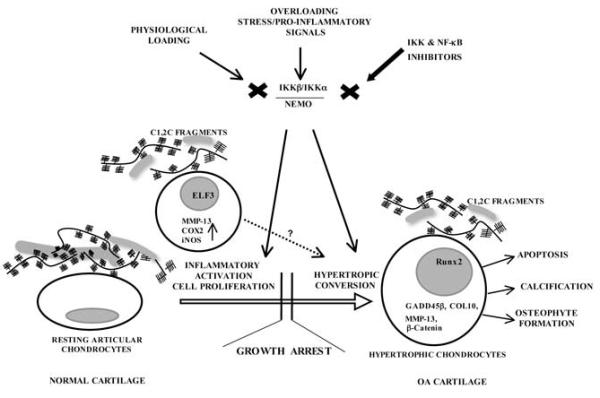

Among the downstream signaling pathways triggered by the inflammatory factors, the NF-κB pathway stands as the central regulator of their catabolic actions, mediating crucial events in the inflammatory responses of chondrocytes and leading to extracellular matrix (ECM) damage and cartilage erosion [74,80,81]. Indeed, the NF-κB pathway is essential for the chondrocytes to express inflammation-related genes, including MMP-1, 3 and 13, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS/NOS-2), IL-6, IL-1, TNFα, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 [75,80,82], and transcription factors such as ELF3/ESE-1 [83]. Figure (2) illustrates some of the more prominent effects of NF-κB activation on inflammation and the hypertrophic-like conversion of articular cartilage chondrocytes in the context of OA disease.

Figure 2. Routes by which IKK mediated NF-κB activation could contribute to the loss of chondrocyte homeostasis in normal cartilage.

The figure depicts effects of the NF-κB activating signalosome complex on specific articular chondrocytes in an OA disease setting. Initially, NF-κB activation could have multiple perturbing effects on chondrocyte physiology, including the activation of stress-related pathways, resulting in the production of inflammatory mediators and cell proliferation, Separate from or perhaps in conjunction with these latter effects, NF-κB signaling could also influence over time the progression of articular chondrocytes to a hypertrophic-like differentiated state. Together, these different NF-κB regulated processes are envisioned to contribute to OA onset and/or progression.

A number of biomechanical and inflammatory insults can lead to iNOS overexpression in different cell types, including chondrocytes [84]. OA chondrocytes overexpress iNOS [85] and its product, NO [86], indicating that this proinflammatory mediator could contribute to OA disease by amplifying and perpetuating the catabolic processes triggered by inflammatory stimuli. Indeed, NO activates MMPs, increases proteoglycan degradation, reduces the production of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-RA) and mediates chondrocyte apoptosis [84]. Accordingly, studies in vivo have indicated that iNOS blockade protects from cartilage degradation. Namely, iNOS-deficient mice are protected from experimental arthritis [87] and in vivo iNOS inhibition results in attenuation of OA progression accompanied by reduced MMP activities [88]. As for iNOS, an inflammatory modulator such as IL-1β, TNFα, LPS or mechanical overload is required for COX2 expression (reviewed in [89]). After induction, COX-2 participates in the sequential enzymatic reactions that lead to the synthesis of PGE2, which, by binding to the EP2 and EP4 PGE2 receptors present in the joint tissues, play a major role in cartilage degradation and OA progression [89]. For example, PGE2 participates in IL-1β-induced MMP-2 expression and activation [90] and induces apoptosis [91] in articular chondrocytes. Moreover, depending on dose and specific redox derivatives, NO can also have negative, as well as positive effects on OA progression, with specific NO derivatives sustaining NF-κB activation in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli and other forms of NO inhibiting its induction (reviewed in [84]).

ELF3 (also called epithelial-specific ETS factor, or ESE-1) is a member of the ETS family of transcription factors [92,93] whose expression is mostly restricted to epithelial-derived tissues during normal conditions but highly induced by IL-1, TNFα or LPS in non-epithelial cells [83]. ELF3 induction relies on the nuclear translocation of canonical NF-κB subunits and subsequent transactivation of the ELF3 promoter via a high affinity proximal NF-κB binding site [83,94]. After induction, ELF3 acts as a central mediator of the inflammatory responses triggered by IL-1, TNFα and LPS [83] transactivating iNOS [94] and COX-2 [95] promoters by direct binding to two or more functional ETS sites, and cooperating with NF-κB. Moreover, ELF3 transactivates the IL-6 promoter and modulates the IL-6 expression induced by LPS in vivo [96]. In chondrocytes, ELF3 accounts for the IL-1-mediated repression of the type II collagen promoter by binding to at least two tandem ETS sites upstream of -131bp [97]. In addition, ELF3 protein levels are higher in OA chondrocytes [97]. We recently found that ELF3 participates in the IL-1-induced MMP-13 expression in chondrocytes, where it transactivates the MMP-13 promoter by direct binding to proximal ETS binding sites (M. Otero et al., in preparation), accounting for the molecular interplay on AP-1 and PEA3/ETS sites in the positive regulation of the MMP-13 promoter [98].

In addition to the deregulated cytokine activities, NF-κB participates in the chondrocyte catabolic responses to ECM degradation products and mechanical stress. The imbalanced chondrocyte homeostasis during OA leads to cartilage erosion and release of ECM matrix components that, in turn, are recognized by specific cell surface receptors and trigger inflammatory responses, aggravating and perpetuating the cartilage erosion. Indeed, NF-κB mediates the chondrocyte activation triggered by fibronectin fragments leading to the increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, MMPs or chemokines and other proteins [99]. Moreover, injurious mechanical stress (i.e. overloading or mechanical stress of high magnitude) is a major risk factor for OA, because chondrocytes via cell surface mechanoreceptors activate the same signaling pathways as those induced by IL-1 and TNFα, including NF-κB activation and translocation, and expression of proinflammatory genes [100,101]. Since these pathways also induce or amplify the expression of cytokine genes, it remains controversial whether inflammatory cytokines are primary or secondary regulators of cartilage damage and defective repair mechanisms in OA.

Chondrocyte homeostasis and evidence of its disruption by progression towards a hypertrophic-like differentiated state in OA disease

Articular cartilage is defined as “permanent”, as opposed to the “temporary” cartilage anlagen, which functions as a template for bone development. The status of chondrocytes in normal articular cartilage is actively maintained by survival mechanisms that prevent these cells from progressing along a terminal differentiation pathway, but that fail in aging or OA [102]. OA, chondrocytes display a phenotype of terminally differentiated cells, with increased expression of hypertrophy markers, such as MMP-9, MMP-13, COL10A1, and alkaline phosphatase [103], which are then followed by signs of terminal differentiation, such as VEGF, osteocalcin, apoptosis and matrix calcification. In fact, the differentiation reprogramming of chondrocytes towards a hypertrophic phenotype during OA has been proposed as a “developmental model” for the disease [10].

Type X collagen, a marker of the hypertrophic chondrocyte that is normally absent in adult articular cartilage, has been detected in certain stages in OA or in atypical sites in OA cartilage [1,104]. In addition to COL10A1, which encodes type X collagen, and MMP13, other genes associated with growth plate development, such as MMP9 and Indian hedgehog (IHH) are expressed in the vicinity of early OA lesions [11]. Surprisingly, decreased levels of Sox9 mRNA, the master switch for the COL2A1-expressing chondrocyte, are detected near the lesions [11], and the expression of this factor, which is required for activation of COL2A1 transcription, does not localize with COL2A1 mRNA in adult articular cartilage [105].

Control of chondrocyte differentiation in vitro and in vivo

During in vitro expansion, chondrocytes gradually lose type II collagen expression [106], but maintain or regain their differentiated phenotype in high density monolayer or 3-dimensional culture conditions, which mirror their spherical shape in vivo [4,107], thus providing model systems to dissect chondrocyte regulatory parameters that are altered in differentiation and also stress-related responses. Moreover, by recapitulating steps in endochondral ossification, chondrocytes in micromass cultures also exhibit phenotypic plasticity akin to mesenchymal stem cells undergoing chondrogenesis [3].

Chondrogenesis in vivo is orchestrated, in part, by Sox9 and Runx2, two pivotal transcriptional regulators that determine the fate of chondrocytes to remain within cartilage or undergo hypertrophic maturation prior to ossification [7,9]; and is subject to complex regulation by interplay among the FGF, TGFβ, BMP and Wnt signaling pathways [7,108-110]. To drive expression of target genes, TGFβ and BMP signaling pathways operate by inducing the nuclear translocation of Smads2/3 and Smads1/5, respectively. The delicate balance between TGFβ and BMP signaling influences the chondrocyte maturation program, whereby TGFβ-regulated Smads2/3 act to maintain articular chondrocytes in an arrested state and BMP-regulated Smads1/5 accelerate their differentiation {reviewed in [102,103,111]}. Sox9, the master chondrocytic transcription factor, has a biphasic behavior with highest expression in proliferating chondrocytes and opposing positive and negative effects on the early and late stages of chondrogenesis, respectively [7,9,112-114]. Two related proteins, Sox5 and Sox6, which are targets of Sox9 itself, enhance the central role of Sox9 in chondrogenesis; together they function as architectural HMG-like chromatin proteins and enhancers of chondrocyte-specific genes, including Col2A1, Col9 and AGC (aggrecan) [9,112,114,115]. The essential role of BMP signaling in chondrocyte maturation via type I receptors, BMPR1A and BMPR1B, is due in part to their redundant capacity to drive chondrogenesis via Sox9, Sox5 and Sox6 [116].

Additional complexity in the onset and control of the terminal phase of chondrogenesis derives from findings on the opposing effects of Sox9 and β-Catenin (the downstream nuclear effector of canonical Wnt signaling) [117-121] and on Runx2, which drives the terminal phase of chondrogenesis [7,122] and is subject to direct inhibition by Sox9 [123]. The equilibrium between Sox9 and β-catenin can also have an important influence on chondrocyte homeostasis. Sox-9 was originally shown to inhibit β-catenin activation and also to increase its prote0some-mediated degradation [120]. Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays a key role in facilitating chondrocyte differentiation, and intermediates of this key signaling pathway are increased in OA [119,124-126]. Elevated levels of intranuclear Sox-9 have more recently been shown to increase β-catenin destruction by stabilizing its degradation complex [127].

Chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation can be driven by the NF-κ B pathway

A link between inflammation and inappropriate differentiation has been proposed via the effects of IL-8/CXCL8 and GROα/CXCL1 [128]. Expression of these chemokines is increased in OA chondrocytes [129] following IKK activation, an event that does not necessarily require delivery of an inflammatory stimulus, but that can be triggered by ECM degradation fragments [99] or other stimuli of the chondrocyte microenvironment. In vitro studies in conjunction with microarray and computational analysis have shown that production of these chemokines is NF-κB dependent [130]. IL-8/CXCL8 and GROα/CXCL1 were able to induce in vitro expression of hypertrophy markers (COL10A1, MMP-13 and alkaline phosphatase), as well as matrix calcification. Noteworthy, up-regulated IL-8 and GROα also result in increased activity of chondrocyte transglutaminases (TGs) in a p38-dependent manner. TG2 is essential for chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation and calcification [128], acting as a molecular switch for hypertrophic conversion when bound to external GTP [131,132]. Moreover, IL-8 has also been found to promote chondrocyte hypertrophy by modulating chondrocyte expression of the type III sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate (Pi) co-transporter “phosphate transporter/retrovirus receptor 1 (PiT-1) [133]. Terkeltaub has provided an extensive review of these and other collaborative factors that influence the progression of growth arrested chondrocytes to a hypertrophic-like state in OA disease [134]

Importantly, pro-inflammatory activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway can also facilitate chondrocyte differentiation towards a hypertrophic-like state by affecting the activities of pivotal regulatory factors. Activation of NF-κB was shown to inhibit mesenchymal chondrocytic differentiation through the transcriptional and post-transcriptional down-modulation of Sox9 mRNA [135,136]. Thus it follows from the different effects of Sox9 in the chondrogenic program that chronic NF-κB activation in OA chondrocytes could inhibit the early pre-hypertrophic phase, while simultaneously promoting the terminal hypertrophic phase. In the context of cartilage, Sox9 is not the only downstream target affected by pro-inflammatory, NF-κB-activating stimuli. Indeed, pro-inflammatory, NF-κB-activating, stimuli also activate the expression of pro-hypertrophic regulatory factors such as BMP-2 and Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible (GADD) 45β.

BMP-2 promotes chondrocyte terminal differentiation by regulating the expression of type X collagen, MMP-13 and alkaline phosphatase [137-139]. The NF-κB subunits p50 and p65 bind to sites in the −2712/+165 BMP-2 promoter region resulting in its transactivation in growth plate chondrocytes [140]. In articular chondrocytes, TNFα induces the expression of BMP-2 via NF-κB and p38 interaction [141]. In addition, BMP-2 is up-regulated in OA cartilage [142], suggesting a role for BMP-2 in OA disease by controlling chondrocyte anabolism or by triggering the expression of genes that lead to a hypertrophic phenotype, such as GADD45β [138,143].

GADD45□ is induced by both BMP-2 and NF-κB (p65/p50) in chondrocytes [138]. In turn, GADD45□ modulates stress-responsive MAP kinases by binding to MTK1 to activate MAP2Ks, such as MKK6 or MKK3, transducing signals to p38 and JNK [144-146]. In chondrocytes, GADD45□ increases MMP-13 promoter activity via JNK activation [138] and enhances C/EBPβ-mediated transactivation of the type X collagen promoter via MTK1/MKK3/6/p38 (Otero, M and Goldring, MB in preparation). Moreover, GADD45β is one of the factors contributing to the imbalance in matrix remodeling in OA cartilage by suppressing COL2A1 gene expression [143]. Interestingly, both C/ebpβ and Gadd45β knockout mice show delayed growth plate hypertrophic chondrocyte differentiation along with decreased Mmp13 and type X collagen expression [138,147]. In addition, C/ebpβ haploinsufficient mice are protected from experimental OA development, showing lower cartilage degradation and type X collagen expression [147]. Together, these findings suggest a role for GADD45β in chondrocyte hypertrophy and OA-related processes by driving the expression of MMP13 and type X collagen coordinately with C/EBPβ. Finally, GADD45β has been proposed to contribute to the homeostasis of normal and early OA articular chondrocytes as an effector of cell survival [143]. .

In other recent work, we investigated the roles of IKKα and IKKβ in articular cartilage homeostasis by ablating their expression in primary human articular chondrocytes (derived from OA patients) with targeted shRNA-expressing retroviruses [148]. Primary human OA chondrocytes in micromass cultures were employed as a convenient means to elicit their progression towards a more hypertrophic-like differentiated state. Because ECM remodeling is the dominant rate-limiting process culminating in chondrocyte hypertrophy, we focused our attention on the potential influences of IKKα and IKKβ on the amounts and ultrastructural organization of the main ECM components, collagens and aggrecan, in micromasses established from control and IKK knock-down {KD} chondrocytes. Stable knockdown of IKKα or IKKβ compromised ECM remodeling by different mechanisms to different extents. IKKα KD resulted in the accumulation of collagen fibers, fibrils and aggrecan, while IKKβ KD more strongly enhanced the deposition of modified proteoglycans [148]. The enforced expression of a phosphorylation- and degradation resistant IκBα super-repressor produced similar results as IKKβ KD. Moreover, other differential IKK effects included higher levels of Sox9 protein in IKKβ KD cells, whereas IKKα KD resulted in Runx2 suppression. Sox9 protein levels were somewhat lower in the absence of IKKα even though modest increases in COL2A1 mRNA were observed in either IKKβ- or IKKα deficient chondrocytes [148]. Articular chondrocytes of IKKα KD micromasses appeared to be blocked at the pre-hypertrophic, periarticular stage by multiple criteria including smaller cell size, extensively organized ECM {particularly with respect to type II collagen deposition}, higher viability, and scant evidence of calcium deposition or mineralization [148]. Importantly, knockdown of IKKβ, but not IKKα, compromised the pro-inflammatory induction of MMP13 RNA and protein, while IKKα ablation severely compromised MMP-13 activity, as assessed by the absence of Col2-3/4C neo-epitopes in IKKα KD cells [148]. Our more recent findings indicate that IKKα may act independent of its kinase activity and NF-κB in this in vitro context and it also appears to influence MMP-13 and aggrecanase activities at least in part by controlling TIMP3 protein levels [149] (Olivotto et al., in preparation).

Since MMP-13 KO mice thrive throughout adulthood with normal cartilage formation and bone growth, (aside from somewhat enlarged hypertrophic zones in the joints of new born mice, which are eventually resolved by adulthood) [150,151], and because these same mice are protected from cartilage degradation induced by surgical OA [20], the functional properties of IKKα in articular chondrocytes, akin to the contrasting catabolic and anabolic roles of MMP-13 and TIMP3 in chondrocyte homeostasis, could potentially have an important impact on either the onset or progressive severity of osteoarthritis. Thus, we posit that IKKα may only significantly influence ECM remodeling when growth-arrested articular chondrocytes are coaxed to differentiate towards hypertrophy, aspects of which are recapitulated ex vivo in micromass cultures, as we have reported [148], or in vivo under the exacerbated stress associated with the onset and progression of OA disease. This notion of an unnatural role for IKKα in de-regulated ECM integrity is also supported by the lack of chondrogenic defects in CK14-Ikkα mice [56].

Strategies for inhibiting NF-κB signaling

OA progression and development involve both biomechanical and biochemical factors that alter chondrocyte homeostasis [61,74]. As a result articular cartilage loses structural organization and function, leading to its irreversible destruction, which chondrocytes are unable to repair [61,74]. Because chondrocytes are the sole cell type present in the articular cartilage, and their expression of inflammatory markers and phenotypic shift during disease are believed to play central roles in OA pathology, therapeutic approaches have focused on the chondrocyte as the main OA target (reviewed in [7,74]). However, efficacious approaches to impede the destructive progression of OA disease have yet to be developed. Research on targets relevant to OA disease has focused on exogenous insults that trigger chondrocyte de-regulation and the endogenous factors that lead to the expression of inflammatory and hypertrophic-like factors in OA chondrocytes, including: (1) the IL-1 receptor, (2) JNK and MAPK dependent cytokine signaling, (3) MMP expression and activities and (4) pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling, amongst other pathways [7,74]. Because the NF-κB signaling pathway responds to most injurious stimuli that affect cartilage to trigger OA and thereby brings about chondrocyte pro-inflammatory and phenotypic changes in affected cartilage tissue, targeting NF-κB signaling in OA disease in ways that avoid undesirable physiological side-effects is of paramount importance [80-82]

Biomechanical loading inhibits NF-κB activation in chondrocytes: significance for targeting NF-κB in OA disease

Cartilage is sensitive to biomechanical signals and downstream effects are conditioned by their magnitude, frequency and duration [101]. Chondrocytes in cartilage are exposed to axial compressive loading or tensile and shear forces. Dynamic compressive or tensile forces at low/physiological magnitudes are anabolic (increased synthesis of type II collagen, aggrecan, TIMP, and COMP) and anti-inflammatory, being able to counteract IL-1β-dependent induction of pro-inflammatory genes (iNOS, COX-2, MMPs, ADAMTS and ADAMTS5), and IL-1β-dependent inhibition of ECM protein synthesis. Indeed, beneficial effects of physiological mechanical loading have also been observed with primary chondrocytes derived from OA patients [152]. Importantly, the beneficial, biomechanical effects of cyclic tensile strain (CTS) are sustained, despite the persistent presence of pro-inflammatory stimuli [101]. In contrast, dynamic compressive or tensile forces of high magnitude and long lasting static forces are pro-inflammatory and inhibit ECM formation [101,153]. Subjecting chondrocytes to dynamic tensile strain has been reported to inhibit NF-κB activation and nuclear translocation, while high magnitude mechanical signals activate NF-κB as strongly as pro-inflammatory stimuli [101,154]. Transmembrane α5β1 integrin receptor, the chondrocyte “mechanoreceptor”, is involved in the delivery of these signals [101,155]. The anabolic and anti-inflammatory actions of physiological mechanical loading also appear to be mediated by secretion of the anabolic cytokine IL-4 in conjunction with cross-talk between integrin and IL-4 receptor signaling [156]

Surprisingly, the inhibitory effects of CTS on NF-κB activation are complex, occurring at multiple levels of canonical NF-κB signaling including: (A) suppression of TGF-β-activating kinase (TAK1) activation, (B) inhibition of IκBα and IκBβ phosphorylation and subsequent proteosomal degradation, (C) inhibition of IKKβ dependent NF-κB Ser536 phosphorylation and (D) down-regulation of IL-1β-induced IκBα mRNA transcription. Interestingly, part of the dynamic mode of CTS action involves alterations in IκBα and NF-κB cytoplasmic-nuclear shuttling. In the initial 30 minutes of the response, IκBα is translocated to the nucleus where it scavenges NF-κB p65 to prevent its DNA binding and then at later times IκBα brings p65 back into the cytoplasm [154]. Importantly, sustained CTS-mediated inhibition of NF-κB function did not adversely affect chondrocyte physiology thus suggesting that modest, targeted inhibition of NF-κB signalling could produce beneficial outcomes in OA disease without adverse effects.

Targeting steps in NF-κ B signaling for inhibition in arthritic disease

A burgeoning list of strategies to block NF-κB signaling have been developed over the past decade and utilized in a variety of inflammatory disease settings but work on OA disease in this regard remains in its infancy. Figure (3) provides an up-to-date overview of the modes of action of specific types of inhibitors and where they are targeted in NF-κB signaling. Most anti-inflammatory compounds (synthetic or natural products) inhibit some aspect of NF-κB activation, starting from the IKK-mediated phosphorylation of the IκBs in the cytoplasm to the transcriptional induction of direct NF-κB target genes in the nucleus. Thus, Figure 3 shows that NF-κB signaling can be inhibited by multiple angles at different steps. The IKKβ subunit of the IKK complex can be inhibited with exquisite specificity by a number of efficacious compounds including SC-514 [157], KINK-1 [158], TPCA-1 [159], BMS-345541 [160], AS-602868 [161] and more recently PHA-408 [162], as well as other natural products including curcumin/diferuloylmethane [163,164] and trans-Resveratrol [165] {see Fig. (3)}. A number of other natural product inhibitors of the IKKs are discussed in prior reviews [80,166]. IKK inhibitors either block ATP binding to IKKβ or directly inhibit its ability to phosphorylate the amino terminus of IκBα. A peptide that blocks the interaction of IKKβ with its NEMO/IKKγ docking protein has also been shown to ameliorate inflammatory disease states [167]. Proteosome inhibitors can also be used to block NF-κB signaling by preventing IκBα degradation (reviewed in [80,81]) but will also block other 26S proteosome dependent cellular functions. In the latter regard, targeted IκBα ubiquination blockers like GS-143 may offer a higher degree of NF-κB pathway specificity [168]. Blocking the nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits can be achieved by introducing an IκBαSR (IκBα super-repressor) mutant protein, which is resistant to amino terminal IKK phosphorylation (reviewed in [80]) or by the action of specific peptides corresponding to nuclear localization sequences (NLSs) or a p65 phosphorylation site (reviewed in [81]). Moreover, NF-κB signaling can also be inhibited by a variety of electrophilic compounds, including 15d-PGJ2, CDD0 and (−)-DHMEQ, which covalently modify specific cysteines in the activation loop of IKKβ [169-171] or the DNA binding domain of NF-κB p65 [169,172,173] {see Fig. (3)}; but these compounds are not specifically targeted to the NF-κB pathway and can also covalently modify reactive cysteines of other cellular proteins. Some of the more promising targeted approaches to specifically reduce NF-κB signaling and activity in vivo involve the use of siRNAs targeted to the IKKs or NF-κB subunits [80,148,174], or decoy oligodeoxynucleotides containing a consensus p65/p50 binding site that competes for the binding of endogenous p65/p50 heterodimers to their target sequences [80,175] {see Fig. (3)}. Finally the transcriptional induction of NF-κB target genes can be inhibited by ligand-dependent trans-repression, mediated by agonistic ligands of the GR, PPARγ and LXR nuclear receptors [176-180]. Depending on the specific receptor, the latter occurs by interfering with the recruitment of co-activators or general transcription factors to NF-κB target gene promoters or also by the direct recruitment of transcriptional co-repressor complexes to NF-κBs bound to their target genes [176,180-183]. More recently specific dissociated GR agonists (SEGRA for Selective GR Agonists) along with other targeted, dissociated agonists of the PPARγ and LXR nuclear receptors have been developed, which maintain transrepression activity but with diminished transactivation side effects [177,180,184-188] {see Fig. (3)}.

Figure 3. Six modes (A-F) of blocking NF-κB activty by specific classes of inhibitors.

Specific drugs or other targeted strategies that block NF-κB function are indicated, as are direct gene targets of activated NF-κBs. The most current, efficacious and specific modalities are underlined in bold face type (see text for literature citations).

NF-κB inhibition strategies have been used in studies with animal rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease models, which have reported reduced inflammation in conjunction with reductions in cartilage degeneration, with some representative examples discussed below, but comparable work in animal OA disease models is still greatly lacking. In early work, liposome delivery of NF-κB p65 ODNs by intra-articular injection into rats with collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) suppressed the expression of NF-κB regulated inflammatory cytokines (as expected) and importantly were also protective against joint destruction; and Rel−/− and Nfκb1−/− knockout mice and T lineage IκαSR transgenic mice were also protected from CIA development (previously reviewed by [189]). Studies with IKKβ and proteosome inhibitors, adenovirus or recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) delivery of a dominant negative IKKβ mutant (IKKβdN), a Tat-srIκBα chimeric protein and an IKKβ-blocking NEMO binding domain peptide (NBD) reported suppression of inflammation in RA disease models; and in some cases also showed protection from joint tissue destruction [167,190-192]. One particular study with the IKKβ selective inhibitor BMS-345541 by oral administration in a CIA mouse model showed remarkable, dose-dependent efficacy in protection from cartilage destruction and a clinical, therapeutic perspective even afforded protection at low doses after disease onset [160]. Very recently, PHA-408, a highly specific and potent ATP competitive inhibitor targeted to IKKβ, was shown to be highly effective by oral administration in a chronic SCW (streptococcus cell wall)-induced Rat RA model without adverse effects at optimum efficacious doses [162]. One preliminary study with injection of a NF-κB decoy ODN into the knee joints of rats, in which OA was induced by anterior cruciate ligament transection, showed some evidence of retarded joint disease by Mankin 95 scoring criteria [80,175]. In addition, a more recent report of adenovirus-mediated delivery of a p65 siRNA in the knees of surgically induced OA rats showed some evidence of blunted cartilage destruction in the early phase of disease but analysis of effects on cartilage and joint integrity were limited and the long-term effects remain to be explored [174].

Summary and perspectives

We have provided an up-to-date synopsis of the mechanisms of NF-κB signaling, functions of NF-κB subunits and their activating kinases, the influence of NF-κB target genes on chondrocyte physiology, and the contribution of de-regulated NF-κB activation on the onset and/or progression of OA disease. We suggest that the NF-κB signaling pathways provide multiple avenues for targeting OA, because of their contributions not only to pro-inflammatory, stress-related responses, but also because their activation can facilitate chondrocyte differentiation towards a hypertrophic-like state, a complicating factor of OA disease. However, even though highly targeted and efficacious strategies exist for blocking NF-κB signaling or NF-κB transcriptional activity, evaluations of these potentially therapeutic modalities in well-defined animal models of OA disease remain in their infancy. There are pluses and minuses in the use of any strategies that tightly block NF-κB signaling, given its importance for cellular survival in stress-sensitive tissues and its essential roles in innate and adaptive immunity. Importantly in the latter regard, to definitively assess the pros and cons of inhibiting NF-κB signaling in the context of OA disease, future work needs to strive to directly address the individual roles of IKKα and IKKβ in OA disease onset and/or progression by generating mice harboring inducible knockouts of each IKK specifically in murine adult articular chondrocytes for deployment in well-defined OA disease mouse models. Moreover, delivery strategies that seek to selectively target NF-κB inhibitors to the affected cartilage tissue in OA disease and/or seek to down-modulate instead of ablate NF-κB signaling and activity would be more prudent approaches, particularly in the treatment of a non-life-threatening disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by USA NIH grants GM066882 (KBM), AG022021 and R21-AR054887 (MBG), an Arthritis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (MO), the Carisbo Foundation (EO), the Rizzoli Institute, a MIUR 40% Grant and a Progetto Strategico di Ateneo (EO, RMB and KBM) and the Hospital for Special Surgery (MO and MBG). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADAMTS

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs

- AGE

Advanced-glycation-end-products

- ANK

Ankyrin repeat

- BMP

Bone morphogenic protein

- CBP

CREB binding protein

- COMP

Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- COX-2

Cycloogenase-2

- CTS

Cyclic tensile strani

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ESE-1

Epithelial-specific ETS factor

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- GADD45β

Growth arrest and DNA damage 45β

- GR

Glucocorticoid receptor

- H3

Histone H3

- IκB

Inhibitor of NF-κB

- IKK

Inhibitor of NF-κB kinase

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- iNOS

Inducile nitric oxide syntase

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase

- KD

knockdown

- LXR

Liver X receptor

- MAPK

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- MMP

matric metalloproteinase

- NEMO

NF-κB essential modulator

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor κB

- NIK

NF-κB inducine kinase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- OA

osteoarthritis

- ODN

Oligodeoxynucleotide

- PGE2

Prostagalndin E2

- PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- RAGE

Receptor for advanced-glycation-end-products

- RHD

Rel-homology domain

- SEGRA

Selective GR agaonists

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Tak1

TGFβ activating kinase 1

- TGFβ

Transforming growth factor β

- TIMP

Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor α

REFERENCES

- [1].Sandell LJ, Aigner T. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:107–13. doi: 10.1186/ar148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Attur MG, Dave M, Akamatsu M, Katoh M, Amin AR. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:1–4. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tallheden T, Dennis JE, Lennon DP, Sjogren-Jansson E, Caplan AI, Lindahl A. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:93–100. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lin Z, Willers C, Xu J, Zheng MH. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1971–84. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aigner T, Söder S, Gebhard PM, McAlinden A, Haag J. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:391–99. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goldring MB. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1916–26. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1916::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hidaka C, Goldring MB. Curr Rheum Rev. 2008;4:136–47. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ikeda T, Kawguchi H, Kamekura S, Ogata N, Mori Y, Nakamura K, Ikegawa S, Chung U. J. Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23:337–40. doi: 10.1007/s00774-005-0610-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Aigner T, Bartnik E, Sohler F, Zimmer R. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:S138–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tchetina EV, Squires G, Poole AR. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:876–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Xu L, Flahiff CM, Waldman BA, Wu D, Olsen BR, Setton LA, Li Y. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48:2509–18. doi: 10.1002/art.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hu K, Xu L, Cao L, Flahiff CM, Brussiau J, Ho K, Setton LA, Youn I, Guilak F, Olsen BR, Li Y. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2891–900. doi: 10.1002/art.22040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sahebjam S, Khokha R, Mort JS. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:905–9. doi: 10.1002/art.22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xu L, Peng H, Wu D, Hu K, Goldring MB, Olsen BR, Li Y. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:548–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Xu L, Peng H, S. G, Lee PL, Hu K, Ijiri K, Olsen BR, Goldring MB, Li Y. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2663–73. doi: 10.1002/art.22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sunk I, Bobacz K, Hofstaetter JG, Amoyo L, Soleiman A, Smolen J, Xu L, Li Y. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56:3685–92. doi: 10.1002/art.22970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Glasson SS, Askew R, Sheppard B, Carito B, Blanchet T, Ma HL, Flannery CR, Peluso D, Kanki K, Yang Z, Majumdar MK, Morris EA. Nature. 2005;434:644–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kamekura S, Kawasaki Y, Hoshi K, Shimoaka T, Chikuda H, Maruyama Z, Komori T, Sato S, Takeda S, Karsenty G, Nakamura K, Chung UI, Kawaguchi H. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2462–70. doi: 10.1002/art.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Little C, Barai C, Smith S, Burkhardt D, Fosang A, Shah M, Thompson E. Osteoarthritis and Cartlage. 2008;16:S22. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kawaguchi H. Mol Cells. 2008;25:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhu M, Tang D, Wu Q, Hao S, Chen M, Xie C, Rosier RN, O’Keefe RJ, Zuscik M, Chen D. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:12–21. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Karin M, Greten FR. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:749–59. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bonizzi G, Karin M. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Basak S, Kim H, Kearns JD, Tergaonkar V, O’Dea B, Werner SL, Benedict CA, Ware CF, Ghosh G, Verma IM, Hoffmann A. Cell. 2007;128:369–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Cell. 2008;132:344–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Savinova OV, Ghosh G, Hoffmann A. Mol Cell. 2009;34:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoffmann A, Levchenko A, Scott ML, Baltimore D. Science. 2002;298:1241–45. doi: 10.1126/science.1071914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Tergaonkar V, Correa RG, Ikawa M, Verma IM. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:921–3. doi: 10.1038/ncb1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sun SC, Ley SC. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:469–78. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Scheidereit C. Oncogene. 2006;25:6685–705. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hansberger MW, Campbell JA, Danthi P, Arrate P, Pennington KN, Marcu KB, Ballard DW, Dermody TS. J Virol. 2007;81:1360–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01860-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lam LT, Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Wright G, Xu W, Zhao H, Yu X, Dang L, Staudt LM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 2008;105:20798–803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806491106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lawrence T, Bebien M, Liu GY, Nizet V, Karin M. Nature. 2005;434:1138–43. doi: 10.1038/nature03491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li Q, Lu Q, Bottero V, Estepa G, Morrison L, Mercurio F, Verma IM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12425–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505997102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liu B, Yang Y, Chernishof V, Loo RR, Jang H, Tahk S, Yang R, Mink S, Shultz D, Bellone C, Loo JA, Shuai K. Cell. 2007;129:903–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pomerantz JL, Baltimore D. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:693–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shih VFS, Kearns JD, Basak S, Savinova OV, Ghosh G, Hoffmann A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812367106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yang CH, Murti A, Pfeffer SR, Kim JG, Donner DB, Pfeffer LM. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13756–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Saitoh T, Nakayama M, Nakano H, Yagita H, Yamamoto N, Yamaoka S. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36005–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yang CH, Murti A, Pfeffer LM. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:31530–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503120200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zarnegar B, Yamazaki S, He JQ, Cheng G. Proc. Natl .Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3503–08. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707959105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Perkins ND. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Luo JL, Tan W, Ricono JM, Korchynskyi O, Zhang M, Gonias SL, Cheresh DA, Karin M. Nature. 2007;446:690–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhu F, Xia X, Liu B, Shen J, Hu Y, Person M, Hu Y. Molecular Cell. 2007;27:214–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yoshida K, Ozaki T, Furuya K, Nakanishi M, Kikuchi H, Yamamoto H, Ono S, Koda T, Omura K, Nakagawara A. Oncogene. 2008;27:1183–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hu Y, Baud V, Delhase M, Zhang P, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. Science. 1999;284:316–20. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Takeda K, Takeuchi O, Tsujimura T, Itami S, Adachi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Yoshikawa K, Terada N, Akira S. Science. 1999;284:313–6. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Li Q, Lu Q, Hwang JY, Buscher D, Lee KF, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Verma IM. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1322–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hu Y, Baud V, Oga T, Kim KI, Yoshida K, Karin M. Nature. 2001;410:710–4. doi: 10.1038/35070605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cao Y, Bonizzi G, Seagroves TN, Greten FR, Johnson R, Schmidt EV, Karin M. Cell. 2001;107:763–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Ca Y, Makris C, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. Immunity. 2002;17:525–35. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Caamano JH, Rizzo CA, Durham SK, Barton DS, Raventos-Suarez C, Snapper CM, Bravo R. J Exp Med. 1998;187:185–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Franzoso G, Carlson L, Poljak L, Shores EW, Epstein S, Leonardi A, Grinberg A, Tran T, Scharton-Kersten T, Anver M, Love P, Brown K, Siebenlist U. J Exp Med. 1998;187:147–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sil AK, Maeda S, Sano Y, Roop DR, Karin M. Nature. 2004;428:660–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Reinhold MI, Naski MC. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:3653–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Liu Z, Xu J, Colvin JS, Ornitz DM. Genes Dev. 2002;16:859–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.965602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Liu Z, Lavine KJ, Hung IH, Ornitz DM. Dev Biol. 2007;302:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Bobick BE, Thornhill TM, Kulyk WM. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:233–43. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Goldring MB, Otero M, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K, Li Y. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:75–82. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.098764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Price JS, Waters JG, Darrah C, Pennington C, Edwards DR, Donell ST, Clark IM. Aging Cell. 2002;1:57–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Roach HI, Yamada N, Cheung KS, Tilley S, Clarke NM, Oreffo RO, Kokubun S, Bronner F. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3110–24. doi: 10.1002/art.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Roach HI, Aigner T. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:128–37. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].da Silva MA, Yamada N, Clarke NM, Roach HI. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:593–601. doi: 10.1002/jor.20799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bank RA, Bayliss MT, Lafeber FP, Maroudas A, Tekoppele JM. Biochem J. 1998;330(Pt 1):345–51. doi: 10.1042/bj3300345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].DeGroot J, Verzijl N, Bank RA, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW, TeKoppele JM. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1003–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<1003::AID-ANR20>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Loeser RF, Yammani RR, Carlson CS, Chen H, Cole A, Im HJ, Bursch LS, Yan SD. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2376–85. doi: 10.1002/art.21199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].DeGroot J, Verzijl N, Wenting-van Wijk MJ, Jacobs KM, Van El B, Van Roermund PM, Bank RA, Bijlsma JW, TeKoppele JM, Lafeber FP. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1207–15. doi: 10.1002/art.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cecil DL, Johnson K, Rediske J, Lotz M, Schmidt AM, Terkeltaub R. J Immunol. 2005;175:8296–302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Yammani RR, Carlson CS, Bresnick AR, Loeser RF. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2901–11. doi: 10.1002/art.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Steenvoorden MM, Huizinga TW, Verzijl N, Bank RA, Ronday HK, Luning HA, Lafeber FP, Toes RE, DeGroot J. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:253–63. doi: 10.1002/art.21523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Goldring MB. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2000;2:459–65. doi: 10.1007/s11926-000-0021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Goldring M, Marcu K. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009;11:224–39. doi: 10.1186/ar2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Scanzello CR, Plaas A, Crow MK. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:565–72. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32830aba34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bobacz K, Sunk IG, Hofstaetter JG, Amoyo L, Toma CD, Akira S, Weichhart T, Saemann M, Smolen JS. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1880–93. doi: 10.1002/art.22637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Su SL, Tsai CD, Lee CH, Salter DM, Lee HS. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:879–86. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kim HA, Cho ML, Choi HY, Yoon CS, Jhun JY, Oh HJ, Kim HY. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2152–63. doi: 10.1002/art.21951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhang Q, Hui W, Litherland GJ, Barter MJ, Davidson R, Darrah C, Donell ST, Clark IM, Cawston TE, Robinson JH, Rowan AD, Young DA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1633–41. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Roman-Blas JA, Jimenez SA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:839–48. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Saklatvala J. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:305–13. doi: 10.2174/138945007779940115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Berenbaum F. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:616–22. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000133663.37352.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Grall F, Gu X, Tan L, Cho JY, Inan MS, Pettit AR, Thamrongsak U, Choy BK, Manning C, Akbarali Y, Zerbini L, Rudders S, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM, Oettgen P, Goldring MB, Libermann TA. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1249–60. doi: 10.1002/art.10942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:S15–S20. doi: 10.1016/S1063-4584(08)60008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Amin AR, Di Cesare PE, Vyas P, Attur M, Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Stuchin SA, Abramson SB. J Exp Med. 1995;182:2097–102. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Loeser RF, Carlson CS, Del Carlo M, Cole A. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2349–57. doi: 10.1002/art.10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].van de Loo FA, Arntz OJ, van Enckevort FH, van Lent PL, van den Berg WB. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:634–46. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<634::AID-ART10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Pelletier JP, Jovanovic DV, Lascau-Coman V, Fernandes JC, Manning PT, Connor JR, Currie MG, Martel-Pelletier J. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1290–9. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6<1290::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Gabay O, Gosset M, Berenbaum F. In: Osteoarthritis, Inflammation and Degradation: A Continuum. Buckwalter JM, Lotz M, Stoltz JF, editors. IOS Press; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 163–80. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [90].Choi YA, Lee DJ, Lim HK, Jeong JH, Sonn JK, Kang SS, Baek SH. Exp Mol Med. 2004;36:226–32. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Miwa M, Saura R, Hirata S, Hayashi Y, Mizuno K, Itoh H. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:17–24. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Oettgen P, Alani RM, Barcinski MA, Brown L, Akbarali Y, Boltax J, Kunsch C, Munger K, Libermann TA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4419–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Oettgen P. Circ Res. 2006;99:1159–66. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251056.85990.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Rudders S, Gaspar J, Madore R, Voland C, Grall F, Patel A, Pellacani A, Perrella MA, Libermann TA, Oettgen P. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3302–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Grall FT, Prall WC, Wei W, Gu X, Cho JY, Choy BK, Zerbini LF, Inan MS, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM, Goldring MB, Oettgen P, Libermann TA. Febs J. 2005;272:1676–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Wu J, Duan R, Cao H, Field D, Newnham CM, Koehler DR, Zamel N, Pritchard MA, Hertzog P, Post M, Tanswell AK, Hu J. Cell Res. 2008;18:649–63. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Peng H, Tan L, Osaki M, Zhan Y, Ijiri K, Tsuchimochi K, Otero M, Wang H, Choy BK, Grall FT, Gu X, Libermann TA, Oettgen P, Goldring MB. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:562–73. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Mengshol JA, Vincenti MP, Coon CI, Barchowsky A, Brinckerhoff CE. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:801–11. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<801::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Pulai JI, Chen H, Im HJ, Kumar S, Hanning C, Hegde PS, Loeser RF. J Immunol. 2005;174:5781–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Agarwal S, Long P, Seyedain A, Piesco N, Shree A, Gassner R. Faseb J. 2003;17:899–901. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0901fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Knobloch TJ, Madhavan S, Nam J, Agarwal S, Jr., Agarwal S. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:139–50. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i2.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].van der Kraan PM, van den Berg WB. Ageing Res Rev. 2008;7:106–13. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Drissi H, Zuscik M, Rosier R, O’Keefe R. Mol Aspects Med. 2005;26:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Aigner T, Reichenberger E, Bertling W, Kirsch T, Stoss H, von der Mark K. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1993;63:205–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02899263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Aigner T, Gebhard PM, Schmid E, Bau B, Harley V, Poschl E. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:363–72. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Lin Z, Fitzgerald JB, Xu J, Willers C, Wood D, Grodzinsky AJ, Zheng MH. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1230–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.20523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Goldring MB. Methods Mol Med. 2005;107:69–95. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-861-7:069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Jakob M, Demarteau O, Schafer D, Hintermann B, Dick W, Heberer M, Martin I. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81:368–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010501)81:2<368::aid-jcb1051>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Yuasa T, Iwamoto ME. Clin Calcium. 2006;16:150–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Zhong N, Gersch RP, Hadjiargyrou M. Bone. 2006;39:5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Blaney-Davidson EN, van der Kraan PM, Van Den Berg WB. Osteoarthritis and cartilage. 2007;15:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Lefebvre V, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:S69–75. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].de Crombrugghe B, Lefebvre V, Behringer RR, Bi W, Murakami S, Huang W. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:389–94. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Akiyama H, Chaboissier M-C, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2813–28. doi: 10.1101/gad.1017802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Smits P, Li P, Mandel J, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B, Lefebvre V. Dev Cell. 2001;1:277–90. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Yoon BS, Ovchinnikov DA, Yoshii I, Mishina Y, Behringer RR, Lyons KM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5062–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500031102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Tamamura Y, Otani T, Kanatani N, Koyama E, Kitagaki J, Komori T, Yamada Y, Costantini F, Wakisaka S, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19185–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414275200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Hill TP, Spater D, Taketo MM, Birchmeier W, Hartmann C. Dev Cell. 2005;8:727–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Yano F, Kugimiya F, Ohba S, Ikeda T, Chikuda H, Ogasawara T, Ogata N, Takato T, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Chung UI. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:1300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Akiyama H, Lyons JP, Mori-Akiyama Y, Yang X, Zhang R, Zhang Z, Deng JM, Taketo MM, Nakamura T, Behringer RR, McCrea PD, de Crombrugghe B. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1072–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Dev Cell. 2005;8:739–50. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Dong YF, Soung do Y, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ, Drissi H. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:77–86. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Zhou G, Zheng Q, Engin F, Munivez E, Chen Y, Sebald E, Krakow D, Lee B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19004–09. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605170103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Corr M. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:550–6. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Dell’accio F, De Bari C, Eltawil NM, Vanhummelen P, Pitzalis C. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1410–21. doi: 10.1002/art.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Yuasa T, Otani T, Koike T, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Lab Invest. 2008;88:264–74. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Topol L, Chen W, Song H, Day TF, Yang Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808048200. M808048200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Merz D, Liu R, Johnson K, Terkeltaub R. J Immunol. 2003;171:4406–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Borzi RM, Mazzetti I, Macor S, Silvestri T, Bassi A, Cattini L, Facchini A. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:238–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00886-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Sandell LJ, Xing X, Franz C, Davies S, Chang LW, Patra D. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1560–71. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Johnson KA, Terkeltaub RA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15004–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Huebner JL, Johnson KA, Kraus VB, Terkeltaub RA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Cecil DL, Rose DM, Terkeltaub R, Liu-Bryan R. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:144–54. doi: 10.1002/art.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Terkeltaub RA. In: OA, Inflammation and Degradation: A Continuum. Buckwalter J, Lotz M, Stoltz JF, editors. IOS Press; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- [135].Murakami S, Lefebvre V, de Crombrugghe B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3687–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Sitcheran R, Cogswell PC, Baldwin AS., Jr Genes Dev. 2003;17:2368–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1114503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].D’Angelo M, Yan Z, Nooreyazdan M, Pacifici M, Sarment DS, Billings PC, Leboy PS. J Cell Biochem. 2000;77:678–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Ijiri K, Zerbini LF, Peng H, Correa RG, Lu B, Walsh N, Zhao Y, Taniguchi N, Huang XL, Otu H, Wang H, Wang J. Fei, Komiya S, Ducy P, Rahman MU, Flavell RA, Libermann TA, Gravallese EM, Oettgen P, Goldring MB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38544–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504202200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Minina E, Wenzel HM, Kreschel C, Karp S, Gaffield W, McMahon AP, Vortkamp A. Development. 2001;128:4523–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.22.4523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Feng JQ, Xing L, Zhang JH, Zhao M, Horn D, Chan J, Boyce BF, Harris SE, Mundy GR, Chen D. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29130–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Fukui N, Ikeda Y, Ohnuki T, Hikita A, Tanaka S, Yamane S, Suzuki R, Sandell LJ, Ochi T. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27229–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Nakase T, Miyaji T, Tomita T, Kaneko M, Kuriyama K, Myoui A, Sugamoto K, Ochi T, Yoshikawa H. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:278–84. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Ijiri K, Zerbini LF, Peng H, Otu HH, Tsuchimochi K, Otero M, Dragomir C, Walsh N, Bierbaum BE, Mattingly D, van Flandern G, Komiya S, Aigner T, Libermann TA, Goldring MB. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2075–87. doi: 10.1002/art.23504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Takeda S, Bonnamy JP, Owen MJ, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Genes Dev. 2001;15:467–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.845101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Takekawa M, Saito H. Cell. 1998;95:521–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Mita H, Tsutsui J, Takekawa M, Witten EA, Saito H. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4544–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4544-4555.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Hirata M, Kugimiya F, Fukai A, Ohba S, Kawamura N, Ogasawara T, Kawasaki Y, Saito T, Yano F, Ikeda T, Nakamura K, Chung UI, Kawaguchi H. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Olivotto E, Borzi RM, Vitellozzi R, Pagani S, Facchini A, Battistelli M, Penzo M, Li X, Flamigni F, Li J, Falcieri E, Facchini A, Marcu KB. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:227–39. doi: 10.1002/art.23211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Marcu KB, Olivotto E, Pagani S, Facchini A, Borzi RM. Osteoarthritis and Cartlage. 2008;16:S9. [Google Scholar]

- [150].Inada M, Wang Y, Byrne MH, Rahman MU, Miyaura C, López-Otín C, Krane SM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17192–97. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407788101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Stickens D, Behonick DJ, Ortega N, Heyer B, Hartenstein B, Yu Y, Fosang AJ, Schorpp-Kistner M, Angel P, Werb Z. Developmen. 2004;131:5883–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Trindade MC, Shida J, Ikenoue T, Lee MS, Lin EY, Yaszay B, Yerby S, Goodman SB, Schurman DJ, Smith RL. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:729–35. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Agarwal S, Deschner J, Long P, Verma A, Hofman C, Evans CH, Piesco N. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3541–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Madhavan S, Anghelina M, Sjostrom D, Dossumbekova A, Guttridge DC, Agarwal S. J Immunol. 2007;179:6246–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Millward-Sadler SJ, Wright MO, Lee H, Caldwell H, Nuki G, Salter DM. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:272–8. doi: 10.1053/joca.1999.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Millward-Sadler SJ, Khan NS, Bracher MG, Wright MO, Salter DM. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Kishore N, Sommers C, Mathialagan S, Guzova J, Yao M, Hauser S, Huynh K, Bonar S, Mielke C, Albee L, Weier R, Graneto M, Hanau C, Perry T, Tripp CS. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32861–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]