Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors of the Cip/Kip family play critical roles in regulating cell proliferation during embryogenesis. However, these proteins also influence cell differentiation by mechanisms that have remained unknown. Here we show that p57Kip2 is expressed in postmitotic differentiating midbrain dopamine cells. Induction of p57Kip2 expression depends on Nurr1, an orphan nuclear receptor that is essential for dopamine neuron development. Moreover, analyses of p57Kip2 gene-targeted mice revealed that p57Kip2 is required for the maturation of midbrain dopamine neuronal cells. Additional experiments in a dopaminergic cell line demonstrated that p57Kip2 can promote maturation by a mechanism that does not require p57Kip2-mediated inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases. Instead, evidence indicates that p57Kip2 functions by a direct protein–protein interaction with Nurr1. Thus, in addition to its established function in control of proliferation, these results reveal a mechanism whereby p57Kip2 influences postmitotic differentiation of dopamine neurons.

Cell differentiation and withdrawal from the cell cycle are tightly coordinated processes during development. Thus, mechanisms essential for regulation of the cell cycle also influence processes of cell differentiation (1). An important mechanism for cell cycle control involves inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) by CDK inhibitors (Ckis) (2). Members of the Cip/Kip family of Ckis, consisting of p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2, control cell cycle exit and cell differentiation in vivo (1, 3). However, only p57Kip2 has been shown to play essential roles during embryogenesis for which other Ckis cannot compensate (4–6). With the exception of abnormal maturation of retina amacrine interneurons, central nervous system-related deficiencies have not been reported in p57-null mutant mice (6).

Dopamine (DA)-producing cells are generated in the ventral floor of the embryonic midbrain (7, 8). These cells are degenerating in Parkinson's disease and are therefore of major clinical interest (9–11). Early signaling by the secreted factors sonic hedgehog and fibroblast growth factor 8 contributes to patterning events and the establishment of a proliferating dopaminergic progenitor cell population expressing aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (Aldh1a1) (12–14). As dividing progenitor cells stop proliferating, they begin to express the orphan nuclear receptor Nurr1 (NR4A2) (13). Nurr1 lacks a cavity for ligand binding as revealed from the recently solved x-ray crystal structure of the Nurr1 ligand-binding domain and is therefore defined as a ligand-independent member of the nuclear receptor family (15). Nurr1 has been shown to be essential for midbrain DA neuron development because Nurr1 knockout animals lack tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and other dopaminergic characteristics (16–18). Nurr1 is required for sustained expression of DA cell-specific genes, normal cell migration, target area innervation, and cell survival (13, 18, 19). Nurr1 overexpression in stem cells has allowed engineering of DA neurons in culture. These results may prove important in efforts to establish cell replacement therapies in Parkinson's disease (10, 11, 20). Nurr1 may also be more directly associated with neurodegenerative disease because mutations in the human Nurr1 gene have been identified in familial Parkinson's disease (21). However, despite intense interest in understanding the development of DA cells, Nurr1-regulated genes important in DA neuron development have not been previously identified.

In our efforts to understand mechanisms of dopaminergic cell differentiation promoted by Nurr1 we have used the DA-synthesizing neuronal MN9D cell line. Overexpression of Nurr1 in MN9D cells, which show properties of immature dopaminergic cells, results in cell cycle arrest and morphological maturation characterized by flattened cell morphology and extension of long neurites (22). Moreover, Nurr1 expression in these cells leads to a marked up-regulation of dopaminergic markers, increased synthesis and secretion of DA (23). In the present study, MN9D cells were used to identify Nurr1-regulated genes involved in maturation events in developing DA cells. Our studies reveal that Nurr1 up-regulates p57Kip2, which in these cells cooperates with Nurr1 in promoting differentiation of DA cells, possibly by a direct protein–protein interaction. Expression of p57Kip2 in developing DA cells, the requirement of Nurr1 for p57Kip2 expression in these cells, and the phenotype of p57Kip2 genetargeted mice indicate that this Cki plays a corresponding critical role in maturation of developing DA cells in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Animals. The generation and genotyping of Nurr1 and p57kip2 mutant mice was described (4, 16). Littermates were used in all comparative experiments. The following animals and stages were selected for experiments: embryonic day (E) 13.5, Nurr1+/+ (n = 4), –/– (n = 4), p57Kip2+/+ (n = 2), and –/– (n = 2); E18.5, p57Kip2+/+ (n = 6) and –/– (n = 6).

Plasmids. pTRE2-Nurr1 contains the cDNA-coding sequence of Nurr1 cloned into pTRE2 vector (BD Clontech). pCMX-Nurr1 contains the cDNA-coding sequence of Nurr1 cloned into pCMX. pCMX-Nurr11–355, pCMX-Nurr194–598, and pCMX-Nurr1183–598 contain truncated sequences of Nurr1. pCMX-Flag-Nurr1 contains a Flag-tagged version of Nurr1. pCMV-HA-p57Kip2 and pCMV-HA-p57CKmut were gifts of S. Leibovitch (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Villejuif, France) and Y. Xiong (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), respectively. pCMX-asp57Kip2 was obtained by inserting in antisense orientation the NcoI–HindIII fragment from pEX10X-p57Kip2 (gift from J. Massagué, Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York), into expression plasmid pCMX. VP16-p57Kip2 encodes the VP16 activation domain from herpes simplex virus, followed by the full-length cDNA sequence of the mouse p57Kip2. Gal4DBD-Nurr1 (1–262) encodes the first 262 amino acid residues of Nurr1 in frame with the yeast Gal4 DNA-binding domain. The luciferase reporters were used as described (24).

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Differentiation Assay. MN9D and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured and transfected as described (22). The cell line derived from MN9D cells in which Nurr1 expression is under control of tetracycline (MN9D-Nurr1Tet-On) was generated by cotransfection of pTRE2-Nurr1 and pTK-Hygro into MN9D cells expressing the reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator. Cells expressing Nurr1 after culturing in the presence of the tetracycline derivative doxocycline (dox, 2 μg/ml; BD Clontech) were selected and further characterized (23). Differentiation assays were performed as described (22).

Preparation of Nuclear Extracts, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blot Analysis. Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts were made as reported (25). For immunoprecipitation, protein Sepharose-precleared nuclear extracts were incubated with the indicated antibody in nuclear extract buffer overnight at 4°C. Immunocomplexes bound to protein A- or G-Sepharose were collected by centrifugation and washed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. For immunoblot analysis, nuclear-cell extracts or immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS/PAGE and blotted; protein pieces were detected with anti-Flag (Sigma), or anti-hemagglutinin (HA) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) antibodies as described (26).

Immunodetection and Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-Mediated dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay. Anti-TH (Chemicon), p57Kip2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Nurr1 (19) antibodies were used in immunodetection. Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 conjugated anti-IgG were used as secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells and sections were blocked in PBS/0.5% FBS/0.3% triton and successively incubated with primary (4°C, 16 h) and secondary antibodies (room temperature, 1 h). Mounting was with VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories). In situ nuclear DNA fragmentation was measured by TUNEL assay on slides pretreated for TH immunodetection (27).

DNA-Binding Assays and Reporter Gene Assays. Gel mobility retardation assays and reporter gene assays were carried out as depicted (22). The following oligo agcttgagttttaAAAGGTCAtgctcaattt and its 32P-labeled complement was used as a NGFIB response element (NBRE) probe.

Mammalian Two-Hybrid Assay. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with VP16-p57Kip2 and Gal4DBD-Nurr1 (1–262) along with a reporter gene driven by four copies of Gal4-binding sites. The cells were subsequently harvested and analyzed as described (24).

In Situ Hybridization. Plasmids with cDNA of p57Kip2, En1, and TH were gifts of S. Matsuoka (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston), A. Joyner (Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, New York), and K. Kobayashi (Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Nara, Japan), respectively. Slides were incubated with digoxygenin-labeled riboprobes as described (13).

RT-PCR. For PCR amplification, primers were as depicted in ref. 23 and following p21Cip1, CGGTGGAACTTTGACTTCGT and GAGTGCAAGACAGCGACAAG; p27Kip1, CCGAGGAGGAAGATGTCAAA and AAATTCCACTTGCGCTGACT; p57Kip2, GAGAGAACTTGCTGGGCATC and GCTTTACACCTTGGGACCAG.

Results

Expression of Ckis in DA Neurons. In attempts to understand mechanisms of dopaminergic differentiation we used the DA-synthesizing neuronal MN9D cell line that shows properties of immature dopaminergic cells. Overexpression of Nurr1 in MN9D cells results in cell cycle arrest and morphological maturation characterized by flattened cell morphology, extension of long neurites, and increased DA synthesis (22, 23). In a clone derived from MN9D cells in which Nurr1 expression is under control of tetracycline (MN9D-Nurr1Tet-On), cells accumulated in G1 phase of the cell cycle within 24 h of dox treatment, and a mature morphological phenotype of these cells was evident after 48 h (23). In addition, dox treatment increases DA content and the expression of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase and vesicular monoamine transporter 2, indicating an instructive role for Nurr1 in controlling DA synthesis and storage in these cells (23).

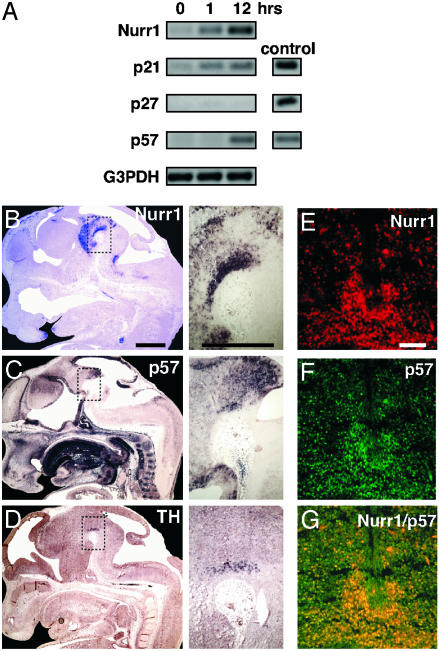

Expression of mRNAs encoding members of the Cip/Kip family in dox-treated MN9D-Nurr1Tet-On cells was analyzed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). p57Kip2 mRNA was markedly up-regulated and accumulated after 12 h of dox treatment of MN9D-Nurr1Tet-On cells. p21Cip1 mRNA was also already up-regulated after 1 h of dox treatment, whereas p27Kip1 mRNA was not induced at any time point analyzed. In control experiments, a subclone of the MN9D cell line expressing the tetracycline-dependent transcription factor was dox-treated to ascertain that the effects on cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and Cki expression depend on Nurr1 expression (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that Nurr1 regulates p21Cip1 and p57Kip2 in MN9D DA cells.

Fig. 1.

p57Kip2 expression is detected in differentiating DA cells in vitro and in vivo. (A) Dox-induced Nurr1 induces p21Cip1 and p57Kip2 mRNA expression. Nurr1, p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2 mRNA content was determined by RT-PCR in MN9D Nurr1Tet-On cells. cDNA-encoding p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2 were used as PCR controls. Sagittal sections of E13.5 wild-type mouse embryos showing Nurr1 (B), p57Kip2 (C), and TH (D) mRNA expression by in situ hybridization analysis. Images on the right are close-ups of the ventral midbrain. Nurr1 was expressed in a broad domain in the ventral midbrain as expected, whereas p57Kip2 mRNA was detected in a more restricted domain coinciding with TH mRNA expression. (E–G) Nurr1 (E) and p57Kip2 (F) immunoreactivity in confocal images of coronal midbrain sections. Overlay is shown in G. (Scale bars: B–D Insets, 100 μm; E–G, 50 μm.)

Next we analyzed if p57Kip2 and p21Cip1 might be regulated by Nurr1 in vivo. The expression patterns of p57Kip2, p21Cip1, and p27Kip1 were analyzed in relation to Nurr1 and TH in the developing mouse brain. In situ hybridization on sagittal sections from E13.5 showed strong Nurr1 expression in the ventral midbrain (Fig. 1B and ref. 28). p57Kip2 was localized predominantly to the ventricular mitotically active cells lining the ventricles (Fig. 1C). p57Kip2 was also detected in the ventral midbrain in a pattern virtually indistinguishable from that of TH and overlapping with the Nurr1 expression domain (Fig. 1C, compare with B and D), indicating that p57Kip2 is expressed in differentiating postmitotic DA cells. Immunohistochemistry and confocal imaging of coronal sections from E13.5 ventral midbrain confirmed p57Kip2 and Nurr1 coexpression in the nuclei of developing DA cells (Fig. 1 E–G). In contrast, p21Cip1 was rather uniformly expressed in the entire central nervous system at E13.5, whereas p27Kip1 expression was not detected in the ventral midbrain (data not shown). Thus, the Nurr1-induced expression of p21Cip1 in MN9D cells does not appear to correspond to a Nurr1-regulated p21Cip1-expression pattern in vivo. To investigate if Nurr1 regulates p57Kip2 expression in developing DA neurons, p57Kip2 mRNA expression was analyzed in wild-type and Nurr1-null mutant mice (Fig. 2). In addition to the mantle zone where p57Kip2 was coexpressed with Nurr1, p57Kip2 was also localized to the adjacent Nurr1-negative ventricular zone (Fig. 2 A). In E13.5 Nurr1-null mouse embryos p57Kip2 mRNA levels were drastically diminished in the mantle zone, but not in the Nurr1-negative ventricular zone (Fig. 2 A–D). Reduced p57Kip2 expression was not due to a cellular deficiency because other DA cell markers, including En1, Aldh1a1, and Ptx3, remain expressed at normal levels at this relatively early developmental stage (Fig. 2 G and H and ref. 13). Thus, Nurr1 is required for p57Kip2 expression in maturing postmitotic DA cells.

Fig. 2.

p57Kip2 expression is down-regulated in the Nurr1 mutant midbrain. Coronal sections of wild-type (A, C, E, and G) and Nurr1-null mutant (B, D, F, and H) ventral midbrain at E13.5 showing in situ hybridization detecting p57Kip2 (A and B), Nurr1 (C and D), TH (E and F), and En1 (G and H) mRNAs. In the Nurr1 mutant midbrain, expression of p57Kip2 is exclusively down-regulated in the mantle zone (mz) but not in the Nurr1-negative ventricular zone (vz) (B). In the wild type, Nurr1, TH, and En1 are expressed in the mantle zone (C, E, and G). Nurr1 and TH were not detected in the Nurr1 mutant ventral midbrain (D and F), whereas expression of En1 remains expressed in Nurr1-deficient cells (H). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

p57Kip2 and Nurr1 Cooperate in the Maturation of MN9D Cells by a Physical Interaction. MN9D cells were used to analyze how p57Kip2 might contribute to the differentiation of DA cells. As shown, Nurr1 induces morphological differentiation of MN9D cells (22). In contrast, overexpression of p57Kip2 alone was not efficient in promoting MN9D cell differentiation, whereas coexpression of both p57Kip2 and Nurr1 drastically increased the number of differentiated cells (Fig. 3A). The rate of cell death or proliferation was not influenced by p57Kip2, indicating that p57Kip2 cooperated with Nurr1 in the process of cell maturation.

Fig. 3.

p57Kip2 enhances DA cell differentiation in vitro and interacts directly with Nurr1. (A) MN9D cells were cotransfected with enhanced GFP (EGFP) expression vector together with expression vectors for Nurrl, p57Kip2, or both. The number of differentiated EGFP-expressing cells was counted 3 days after transfection as described (22). Average values of quadruplicates are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation. (B) p57Kip2 interacts with Nurr1. HEK 293 cells were transfected with the empty expression vector, expression vectors encoding Flag-Nurr1, HA-p57Kip2, or both. Nuclear cell extracts from transfected cells were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-HA or anti-Flag antibodies (Top). Nuclear cell extracts were immunoprecipitated by using anti-Nurr1 (Middle) or anti-p57Kip2 (Bottom) antibodies, and immune complexes were subjected to immunoblotting by using anti-HA or anti-Flag antibodies. (C) p57Kip2 interacts with Nurr1 in extracts from the embryonal ventral midbrain. Total cell extracts were prepared from rat E15 ventral midbrain and immunoprecipitated by using anti-IgG control (left lane) or anti-Nurr1 antibodies (center lane). Immune complexes were subjected to immunoblotting by using anti-p57Kip2 antibodies. Nuclear cell extract from HEK 293 cells transfected with expression vectors encoding p57Kip2 was used as control (right lane). (D) p57Kip2 and Nurr1 proteins interact in transfected cells. The interaction between p57Kip2 and Nurr1 was confirmed by using a mammalian two-hybrid assay. HEK 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors VP16-p57Kip2 and Gal4DBD-Nurr1 (1–262). These vectors were transfected either alone or as indicated in the figure together with a luciferase reporter gene driven by four UAS Gal4-binding sites. Relative light units (RLU) were computed after normalization to β-galactosidase activities. Gal4DBD-Nurr1 (1–262) activates the reporter gene due to the presence of a transactivation domain within the Nurr1 amino-terminal domain. Activation is strongly enhanced by cotransfection of VP16-p57Kip2. (E) A gel-mobility shift assay demonstrated that in vitro transcribed and translated HA-p57Kip2 formed complexes with in vitro translated Nurr1 bound to a 32P-labeled NBRE DNA probe. The positions of Nurr1 (shift) and Nurr1/p57Kip2 complexes (super shift) bound to NBREs are indicated. Coincubation with HA antibodies abolished the binding of p57Kip2 to the Nurr1 bound to NBRE probe. (F) p57Kip2 inhibits Nurr1 activation of a reporter gene containing Nurr1 DNA-binding sites (NBREs). MN9D cells were transfected with a luciferase NBRE reporter plasmid and expression vectors encoding either Nurr1 and/or p57Kip2. (G) In a control experiment, MN9D cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing retinoic acid receptor DNA-binding sites (βREs) and expression vectors encoding p57Kip2. Cells were treated with or without 1 μM all-trans-retinoic acid. RLUs were computed after normalization to β-galactosidase activities.

We speculated that functional cooperativity in MN9D cell maturation might reflect direct protein–protein interaction between p57Kip2 and Nurr1. Indeed, the following observations demonstrated that these two proteins physically interact. (i) Interaction was detected by coimmunoprecipitation from nuclear extracts of HEK 293 cells expressing either Flag-immunotagged Nurr1, HA-immunotagged p57Kip2, or both (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Nurr1 did not interact with p21Cip1 or p27Kip1 (data not shown). (ii) Significantly, protein–protein interaction was detected by coimmunoprecipitation in extracts from E15 rat embryo ventral midbrain (Fig. 3C). Rat rather than mouse tissue was used in this experiment because bigger pieces of ventral midbrain can be dissected from rat embryos. (iii) Physical interaction was also detected in transfected cells by a mammalian two-hybrid assay. In these experiments the interaction between two fusion proteins were analyzed after cotransfection in HEK 293 cells. One fusion protein contains the first 262 amino acids of Nurr1 fused to the yeast transcription factor Gal4 (Gal4-Nurr1). A second fusion protein contains a p57Kip2 derivative fused to the transactivation domain of herpes simplex virus VP16 (VP16-p57) (Fig. 3D). (iv) p57Kip2 and Nurr1 can interact in vitro on a specific Nurr1 DNA-binding site (NBRE) (Fig. 3E). p57Kip2/Nurr1 binding on the NBRE suggested that p57Kip2 might modulate Nurr1 transcriptional activity. Indeed, p57Kip2 exerted a negative influence on reporter gene activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 F and G). In conclusion, our results demonstrate that Nurr1 and p57Kip2 cooperate in inducing maturation of MN9D cells by a mechanism that may depend on direct interaction between these two proteins.

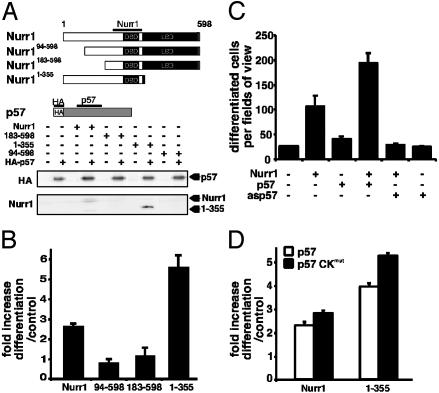

To begin elucidating the significance of the observed protein–protein interaction, we first analyzed structural requirements of Nurr1 for interaction with p57Kip2. Nurr1 derivatives lacking either the entire carboxy-terminal ligand-binding domain/activation function 2 transactivation function (Nurr11–355), the first amino-terminal 93 (Nurr194–598) or 182 (Nurr1183–598) amino acid residues of the AF1 transactivation domain were used in coimmunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 4A). Whereas deletion of the carboxy-terminal ligand-binding domain/activation function 2 domain did not influence interaction with p57Kip2, both the short and long deletion in the amino-terminal domain abolished interactions (Fig. 4A). These data are also consistent with the two-hybrid experiment displayed in Fig. 3D, showing that the amino-terminal domain of Nurr1 is sufficient for interaction with p57Kip2. We then tested the ability of these derivatives to cooperate with p57Kip2 in MN9D cell maturation. The noninteracting derivatives (Nurr194–598 and Nurr1183–598) failed to cooperate with p57Kip2 in inducing maturation of MN9D cells (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the interaction-competent Nurr11–355 derivative retained the ability to cooperate with p57Kip2. In fact, this derivative was even more potent than wild-type Nurr1, perhaps because of an increased ability to interact with p57Kip2 (Fig. 4A). Thus, efficient maturation required expression of both p57Kip2 and Nurr1 derivatives capable of interacting with p57Kip2.

Fig. 4.

p57Kip2 enhances DA cell differentiation in vitro by direct interaction with the amino-terminal domain of Nurr1. (A) HEK 293 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Nurr1, Nurr194–598, Nurr1183–598, or Nurr11–355 either alone or together with a HA-p57Kip2 expression vector. Nuclear cell extracts were immunoprecipitated by using anti-p57Kip2 antibodies, and immune complexes were subjected to immunoblotting by using anti-HA (Upper) or anti-Nurr1 (Lower) antibodies. (B) p57Kip2 is unable to cooperate with interaction-deficient amino-terminally truncated Nurr1 derivatives. MN9D cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding EGFP and Nurr1, Nurr194–598, Nurr1183–598, or Nurr11–355 alone or together with p57Kip2 expression vector. The number of differentiated cells was counted 3 days after transfection as in Fig. 4, and the fold increase was calculated. Error bars represent standard deviation. p57Kip2 is required for Nurr1-induced differentiation but not cell cycle arrest. (C) MN9D cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding EGFP and Nurr1 either alone or together with p57Kip2 or antisense p57Kip2 (asp57) expression vectors. The number of differentiated EGFP-expressing cells was counted 3 days after transfection as in Fig. 4, and the fold increase was calculated. Error bars represent standard deviation. Average values of quadruplicates are shown. (D) MN9D cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding EGFP and Nurr1 or Nurr11–355 either alone or together with p57Kip2 or p57 CKmut expression vectors.

The observed effects on maturation induced by p57Kip2 and Nurr1 suggested that p57Kip2, induced as a result of Nurr1 overexpression, may significantly contribute to the maturation of MN9D cells. Expression of antisense p57Kip2 RNA (asp57) was used to assess the importance of p57Kip2 for MN9D cell maturation (Fig. 4C). Although asp57 expression did not disrupt cell cycle arrest induced by Nurr1 (data not shown), presumably due to Nurr1-induced expression of p21Cip1 (Fig. 1A), asp57 abolished Nurr1-induced cell maturation (Fig. 4C). Thus, these data demonstrate that maturation and cell cycle arrest are independently controlled in these cells.

p57Kip2 Promotes MN9D Cell Maturation by Means of a CDK-Independent Mechanism. To further investigate specific requirements for cell maturation, we used a mutated derivative of p57Kip2 (p57CKmut) (29) that is unable to inhibit CDK activity. The mutation did not interfere with the ability of p57Kip2 to interact with Nurr1 (data not shown). Although p57CKmut is unable to induce cell cycle arrest (29), it retains the ability to cooperate with Nurr1 in MN9D cell maturation (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these data provide compelling evidence, indicating that p57Kip2 promotes DA cell maturation by a mechanism that is independent of its ability to inhibit CDK activity.

p57Kip2 Is Essential for Normal DA Neuron Development in Vivo. The importance of p57Kip2 in MN9D cells and its expression during critical stages of DA cell differentiation in vivo suggested that p57Kip2 might play a role for DA cell development. To verify the role of p57Kip2 in vivo we analyzed p57Kip2-null mice (Fig. 5). DA cells appeared abnormal in the ventral midbrain of E18.5 embryos in the absence of p57Kip2. TH immunoreactivity was drastically reduced in this area (Fig. 5 A and B), but was unaffected in other regions where catecholaminergic neurons are located (Fig. 5 E–H). Thus, the phenotype is selective to midbrain DA neurons. In situ hybridization revealed also that Nurr1 expression was diminished in the ventral midbrain of mutant E18.5 embryos, whereas it remained normal in other regions, e.g., the cortex (Fig. 5 C and D and data not shown). Furthermore, expression of both TH and Nurr1 was particularly weak in lateral regions of the ventral midbrain, suggesting that TH- and Nurr1-expressing cells remained in a medial location in mutant brains (Fig. 5 A–D). Cell proliferation, as determined after BrdUrd administration, was unaltered at several developmental stages in the ventral midbrain of p57Kip2 knockout embryos (data not shown). Finally, occurrence of cell death was analyzed in ventral midbrain of p57Kip2 mutant E18.5 mice. By using a TUNEL assay, more than a 2-fold increase in the extent of apoptotic cell death was revealed specifically in the p57Kip2 mutant ventral midbrain (Fig. 5 I–K). Other areas assayed for apoptotic cells, such as the dorsal midbrain, the cortex, and the olfactory bulb, did not show any differences between the genotypes (data not shown). At earlier stages of development (E13.5) DA cells appeared normal in p57Kip2 mutant embryos consistent with the onset of p57Kip2 expression at late midgestation. Taken together, these results reveal a strict requirement for p57Kip2 in the late maturation of midbrain DA cells. As migration and survival of ventral midbrain cells are affected, we speculate that the expression of Nurr1 and TH may primarily be reduced as a consequence of fewer cells being localized in the appropriate positions in p57Kip2 gene-targeted embryos.

Fig. 5.

Deficient DA neuron development and selective increase in apoptosis in the midbrain dopaminergic area in p57Kip2-null mutant pups. (A–D) Coronal sections of E18.5 wild-type (A and C) and p57Kip2-null mutant (B and D) pups showing TH immunoreactivity (A and B) and Nurr1 mRNA expression (C and D). Expression patterns of TH and Nurr1 appear abnormal in the p57Kip2 mutant ventral midbrain. TH- and Nurr1-expressing cells are almost entirely absent in the lateral regions, and the morphology appears disorganized. Both markers were normally distributed in other brain areas. (C and D Insets) Normal Nurr1 expression in p57Kip2 mutant cortex. (E–G) TH was normally expressed in other catecholaminergic groups, e.g., the locus coeruleus (E and F) and olfactory bulb (G and H). (I–K) A combined TH-staining/TUNEL assay was used on coronal sections to detect apoptotic cells in the E18.5 wild-type and p57Kip2-null mutant ventral midbrain. TUNEL-positive cells in the area of midbrain DA cells were observed and counted in wild-type and p57Kip2 mutant mice. An increase in apoptotic cells in the entire dopaminergic area was observed in the mutant (J) as compared with the wild type (I) as exemplified by these high-magnification images of the medial ventral midbrain. The increase in the mutant was >2-fold greater than the wild type (K) (E18.5, p57Kip2+/+, n = 3; –/–, n = 3; **, P < 0,005). (Scale bars: A–D, 100 μm; Insets, 300 μm; E–J, 200 μm.)

Discussion

Our results suggest a reciprocal relationship between Nurr1 and p57Kip2 whereby Nurr1 activates expression of p57Kip2, which in turn cooperates with Nurr1 in DA cell development. Strikingly, p57Kip2 is essential for Nurr1-induced maturation of MN9D DA cells by a mechanism that is independent of its ability to inhibit CDKs. Instead, our data indicate that p57Kip2 may function as a Nurr1-interacting cofactor. The resemblance in DA cell phenotypes between Nurr1 and p57Kip2 knockout mice is consistent with a mechanism whereby both genes are involved in common regulatory processes. Thus, the data indicate a new role for p57Kip2 as a transcriptional cofactor with functions in neuronal differentiation.

The conclusion that p57Kip2 promotes differentiation of DA neurons in vivo after they have already exited the cell cycle is supported by several observations. First, in the midbrain p57Kip2 is not only expressed in the ventricular zone where cell cycle exit would be regulated, but also in the mantle zone of postmitotic differentiating DA cells. Second, abnormal proliferation was not observed in p57Kip2 knockout embryo ventral midbrain after BrdUrd labeling at several developmental stages (data not shown). Third, the observed p57Kip2 mutant defects appear at a stage when developing DA neurons have already stopped proliferating. Fourth, the DA cell phenotype resembles deficiencies observed in Nurr1 mutant embryos, with deregulation of marker gene expression and increased cell death, indicating a function downstream of Nurr1, which itself is not expressed until after cells have exited the cell cycle (13). We do not exclude the possibility that p57Kip2, together with other Ckis, such as, e.g., p21Cip1, may influence DA cell progenitor proliferation by a redundant mechanism because both of these Ckis are also expressed in ventricular proliferating progenitor cells.

How might p57Kip2 modulate the function of Nurr1 in developing DA neurons? A reporter gene assay indicated that p57Kip2 may have a negative influence on Nurr1's transcriptional activity. p57Kip2, which interacts with the amino-terminal domain of Nurr1, might interfere with coactivator recruitment. However, in a different promoter context it remains possible that interaction between Nurr1 and p57Kip2 might exert a positive influence. Evidently, a detailed understanding of how p57Kip2 modulates Nurr1-dependent transcription has to await the identification of relevant target genes. Nonetheless, the interaction between Nurr1 and p57Kip2 clearly has a potential for modulating Nurr1, as demonstrated by the inhibition of Nurr1-induced reporter gene activity.

Developmental mechanisms in other cell types may likely be analogous to those reported here. Specifically, this would imply that some of the requirements for Ckis are independent of their function as CDK inhibitors. Indeed, previously reported results provide support for this view. For example, p57Kip2 has been shown to promote muscle differentiation in a process that may be influenced by direct interaction with the muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD (30, 31). Moreover, other functions of Cip/Kip Ckis have been reported to be uncoupled from the control of cellular proliferation (6, 32). More versatile functions involving Ckis may thus provide a rational mechanism whereby withdrawal from the cell cycle can be efficiently integrated with subsequent cellular differentiation events. p57Kip2, being the most structurally complex member of the Cip/Kip family of Ckis (33, 34), may be particularly important in this regard. According to this view, p57Kip2 may serve as a platform for multiple protein–protein interactions, thereby promoting distinct developmental processes that help to integrate cell cycle control with activities of cell type-specific transcription factors. Of note, other nuclear receptor activities have been shown to be modulated by cell cycle mediators independently of their role in cell cycle regulation. For example, cyclin D1 can interact with estrogen receptor and thereby enhance its transcriptional activity (35, 36). The retinoblastoma protein can interact with the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ and thereby recruit histone deacetylase HDAC3 to the complex (37).

Because of the involvement in disease, DA neurons represent one of the most intensely studied central nervous system cell types. Most notably, these cells are degenerating in Parkinson's disease for reasons that remain to be fully established. Characterization of DA neuron development may help to reveal processes of relevance for sustained dopaminergic functions and neuronal survival. Perhaps more importantly, understanding developmental mechanisms should be of significance in the use of stem cells specifically designed for therapeutic transplantation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Although the studies presented here have clearly uncovered an essential component in a major regulatory pathway of dopaminergic differentiation in vivo, future work will determine to what extent this knowledge may contribute to attempts to engineer DA neurons from stem cells in vitro.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Barbacid for the p57Kip2 knockout mice; O. Hermanson, J. Ericsson, A. Simon, L. Solomin, and M. Malewicz for helpful comments; and S. Petersson for help with the collection of ventral midbrain tissue. This work was supported by the Göran Gustafsson Foundation, the Human Frontiers Science Program, the European Union, and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: En, embryonic day n; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinases; Cki, CDK inhibitor; DA, dopamine; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling; dox, doxocycline; HA, hemagglutinin; NBRE, NGFIB response element; HEK, human embryonic kidney.

References

- 1.Chellappan, S. P., Giordano, A. & Fisher, P. B. (1998) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 227, 57–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidal, A. & Koff, A. (2000) Gene 247, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham, J. J. & Roussel, M. F. (2001) Cell Growth Differ. 12, 387–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan, Y., Frisen, J., Lee, M. H., Massague, J. & Barbacid, M. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang, P., Liegeois, N. J., Wong, C., Finegold, M., Hou, H., Thompson, J. C., Silverman, A., Harper, J. W., DePinho, R. A. & Elledge, S. J. (1997) Nature 387, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyer, M. A. & Cepko, C. L. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 127, 3593–3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goridis, C. & Rohrer, H. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hynes, M. & Rosenthal, A. (1999) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakurada, K., Ohshima-Sakurada, M., Palmer, T. D. & Gage, F. H. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 4017–4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, J., Auerbach, J., Rodriguez-Gomez, J., Velasco, I., Gavin, D., Lumelsky, N., Lee, S., Nguyen, J., Sanchez-Pernaute, R., Bankiewicz, K. & McKay, R. (2002) Nature 418, 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner, J., Akerud, P., Castro, D. S., Holm, P. C., Canals, J. M., Snyder, E. Y., Perlmann, T. & Arenas, E. (1999) Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynes, M., Porter, J. A., Chiang, C., Chang, D., Tessier-Lavigne, M., Beachy, P. A. & Rosenthal, A. (1995) Neuron 15, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallén, Å., Zetterström, R. H., Solomin, L., Arvidsson, M., Olson, L. & Perlmann, T. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 253, 737–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye, W., Shinamura, K., Rubenstein, J. L. R., Hynes, M. A. & Rosenthal, A. (1998) Cell 93, 755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, Z., Benoit, G., Liu, J., Prasad, S., Aarnisalo, P., Liu, X., Xu, H. F., Walker, N. P. & Perlmann, T. (2003) Nature 423, 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zetterström, R. H., Solomin, L., Jansson, L., Hoffer, B. J., Olson, L. & Perlmann, T. (1997) Science 276, 248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castillo, S. O., Baffi, J. S., Palkovits, M., Goldstein, D. S., Kopin, I. J., Witta, J., Magnuson, M. A. & Nikodem, V. M. (1998) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 11, 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saucedo-Cardenas, O., Quintana-Hau, J. D., Le, W. D., Smidt, M. P., Cox, J. J., De Mayo, F., Burbach, J. P. & Conneely, O. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4013–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallén, Å., Castro, D. S., Zetterström, R. H., Karlen, M., Olson, L., Ericson, J. & Perlmann, T. (2001) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 18, 649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung, S., Sonntag, K. C., Andersson, T., Bjorklund, L. M., Park, J. J., Kim, D. W., Kang, U. J., Isacson, O. & Kim, K. S. (2002) Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 1829–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le, W. D., Xu, P., Jankovic, J., Jiang, H., Appel, S. H., Smith, R. G. & Vassilatis, D. K. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro, D. S., Hermanson, E., Joseph, B., Wallén, Å., Aarnisalo, P., Heller, A. & Perlmann, T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43277–43284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermanson, E., Joseph, B., Castro, D., Lindqvist, E., Aarnisalo, P., Wallén, Å., Benoit, G., Hengerer, B., Olson, L. & Perlmann, T. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 288, 324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlmann, T. & Jansson, L. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 769–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dignam, J. D., Lebovitz, R. M. & Roeder, R. G. (1983) Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joseph, B., Ekedahl, J., Lewensohn, R., Marchetti, P., Formstecher, P. & Zhivotovsky, B. (2001) Oncogene 20, 2877–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joseph, B., Marchetti, P., Formstecher, P., Kroemer, G., Lewensohn, R. & Zhivotovsky, B. (2002) Oncogene 21, 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zetterström, R. H., Williams, R., Perlmann, T. & Olson, L. (1996) Mol. Brain Res. 41, 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe, H., Pan, Z. Q., Schreiber-Agus, N., DePinho, R. A., Hurwitz, J. & Xiong, Y. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1392–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynaud, E. G., Pelpel, K., Guillier, M., Leibovitch, M. P. & Leibovitch, S. A. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7621–7629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reynaud, E. G., Leibovitch, M. P., Tintignac, L. A., Pelpel, K., Guillier, M. & Leibovitch, S. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18767–18776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohnuma, S., Philpott, A., Wang, K., Holt, C. E. & Harris, W. A. (1999) Cell 99, 499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, M. H., Reynisdottir, I. & Massague, J. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 639–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuoka, S., Edwards, M. C., Bai, C., Parker, S., Zhang, P., Baldini, A., Harper, J. W. & Elledge, S. J. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 650–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neuman, E., Ladha, M. H., Lin, N., Upton, T. M., Miller, S. J., DiRenzo, J., Pestell, R. G., Hinds, P. W., Dowdy, S. F., Brown, M., et al. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5338–5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zwijsen, R. M., Wientjens, E., Klompmaker, R., van der Sman, J., Bernards, R. & Michalides, R. J. (1997) Cell 88, 405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fajas, L., Egler, V., Reiter, R., Hansen, J., Kristiansen, K., Debril, M. B., Miard, S. & Auwerx, J. (2002) Dev. Cell 3, 903–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]