Abstract

Approximately 25% of breast cancers do not express the estrogen receptor (ERα) and consequently do not respond to endocrine therapy. In these tumors, ERα repression is often due to epigenetic modifications such as methylation and histone deacetylation. For this reason, we investigated the ability of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat (ENT) to trigger re-expression of ERα and aromatase in breast cancer cells, with the notion that this treatment would restore sensitivity to the aromatase inhibitor letrozole. ENT treatment of tumor cells increased expression of ERα and aromatase along with the enzymatic activity of aromatase, in a dose-dependent manner both in vitro and in vivo. Notably, ERα and aromatase upregulation resulted in sensitization of breast cancer cells to estrogen and letrozole. Tumor growth rate was significantly lower in tumor xenografts following treatment with ENT alone and in combination with letrozole compared to control tumors (p >0.001). ENT plus letrozole also prevented lung colonization and growth of tumor cells with a significant reduction (p>0.03) in both visible and microscopic foci. Our results demonstrate that ENT treatment can be used to restore the letrozole responsiveness of ER-negative tumors. More generally, they provide a strong rationale for immediate clinical evaluation of combinations of histone deacetylase and aromatase inhibitors to treat ER-negative and endocrine-resistant breast cancers.

Keywords: aromatase inhibitor, HDAC, ERα, epigenetic silencing

Introduction

The knowledge that estrogens play a critical role in growth of hormone dependent breast cancer is exploited in the use of endocrine therapy such as antiestrogens (AEs) and aromatase inhibitors (AIs). The development of AIs has led to significant improvements in the treatment of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer in postmenopausal women (1, 2). However, endocrine therapy is limited to patients whose tumors express hormone receptors, namely the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and/or the progesterone receptor (PR). About 25% of breast cancers lack the expression of both hormone receptors and are considered hormone-independent. Systemic therapy for these patients has traditionally been limited to only cytotoxic chemotherapy. Thus, there is a critical need to improve treatment for these women.

Previous reports have suggested that lack of ERα expression in ER-negative breast cancers is due to epigenetic changes, such as increased deacetylation and methylation (3). Histone acetylation and deacetylation are key epigenetic processes that affect gene regulation by changing the DNA conformation in the chromatin. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) is an enzyme that regulates acetylation of histone protein. Recent studies indicate that silencing of a gene by methylation involves the generation of an inactive chromatin structure characterized by deacetylated histones (4). For example, deacetylation of histone results in chromatin condensation, which in turn causes transcriptional repression of gene expression (4). The ERα gene CpG island is extensively methylated in ER-negative breast cancer cells (5) and in about 50% of the primary ER-negative breast tumors but remains unmethylated in normal breast tissue, many ERα positive tumors and cell lines (5). The relevance of this finding was demonstrated when ER-negative human breast cancer cells were treated with demethylating agent 5-azacytidine. This led to reactivation of ERα mRNA and functional ERα protein (6). Studies have shown that repression of ERα can also be reversed by the use of HDAC inhibitors (6). HDACi such as butyric acid (BA) or trichostatin A (TSA) reverse the repression by specific inhibition of HDAC activity, leading to histone hyperacetylation, chromatin relaxation, and enhanced transcription. However, this strategy remains to be tested in preclinical in vivo models of breast cancer.

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that inhibiting HDAC in ER-negative tumors will increase expression of functional ERα and aromatase. Thus, tumor cells with silenced ERα expression would be rendered responsive to growth inhibition by AIs. To test our premise, we used the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor entinostat (ENT/ENT-275/SNDX-275), an oral class-I selective HDAC inhibitor and the aromatase inhibitor, letrozole. Our results showed that treatment with ENT resulted in upregulation of ERα and aromatase expression with consequent inhibition of growth by letrozole of tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. This strategy of converting ER-negative tumors to ER-positive tumors using HDAC inhibitors could provide a new avenue for management of patients with ER-negative breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

ERα-negative MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and SKBR3 cells were obtained from ATCC. These cell lines were authenticated by ATCC using Short Tandem Repeat (STr) profiling, Karyotyping and by monitoring cell morphology. In vitro assay conditions and data analysis are described in the online Supplementary Methods section.

Subcutaneous tumor analysis

All animal studies were performed according to the guidelines and approval of the Animal Care Committee of the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Tumor xenografts of MDA-MB-231 cells inoculated into each flank of the female ovariectomized (OVX) athymic nude mouse as previously described with minor modifications (7-12). Treatment details are provided in online Supplementary Methods section. Tumor volumes were calculated as follows (4/3-πr12r2 where r1 < r2).

Lung colonization assay

Mice received injections of 3 × 106 of MDA-MB-231 cells via the tail vein. Groups of mice were treated three weeks later with vehicle (control), ENT, letrozole, or ENT plus letrozole. Mice were treated for six weeks, and then euthanized.

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared as described previously (7-11, 13) and 50 μg of protein from each sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The densitometric values were corrected using β-actin as a loading control. Details of antibodies used are described in the online Supplementary Methods section.

Aromatase activity

Aromatase activity in cells was determined using a radiometric assay by measuring 3H2O formed on conversion of [1-β3H] Δ4A (aromatase substrate) to estrone (7, 14).

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription (RT) and PCR

RNA was extracted and purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as per manufacturer’s protocol. Analysis of ERα, CYP-19 and pS2 mRNA expression was carried out by conventional RT-PCR as described earlier (8, 15).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (5μM sections). The primary antibodies used were: ERα and Ki67.

Statistics

For in vitro studies, statistical analysis was performed on InStat 3.0 for Mac (GraphPad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA) One-Way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons with the Tukey test. However, if the data did not pass the normality test, a non-parametric test was used such as Kruskal-Wallis analysis with Dunn post test. For in vivo studies, mixed-effects models were used. The tumor volumes were analyzed with S-PLUS (7.0, Insightful Corp.) to estimate and compare an exponential parameter (βi) controlling the growth rate for each treatment groups. The original values for tumor volumes were log transformed. All p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The graphs are represented as mean ± SEM

Results

HDACi ENT induces ERα and aromatase expression in ER-negative breast cancer cells in vitro

Expression of ERα protein was undetectable in MDA-MB-231 cells by western blotting (Supplemental Figure-1) and no significant binding of E2 occurred without ENT treatment (data not shown). In addition, growth of MDA-MB-231 cells was not inhibited by AEs or AIs nor stimulated by estrogen (data not shown). Expression of ERα protein was up-regulated 8 and 9.9-fold after treatment with 10 nM of ENT and SAHA respectively and expression of aromatase was upregulated 2.6 and 1.8 fold with ENT and SAHA respectively (Supplemental Figure-1). Treatment with ENT resulted in upregulation of ERα and aromatase mRNA in a time-dependent manner; an increase was observed in as early as 15 minutes (Figure-1A). The effect of the two HDACis was similar in other ER-negative cell lines, SKBr3 and Hs578T (data not shown). However, ENT was more effective in induction of both ERα and aromatase and was therefore selected for further study.

Figure-1.

(A) Time Course of ENT Effect on mRNA Expression of ERα and Aromatase: Expression of mRNA was examined in MDA-MB-231 cells by RT-PCR at different time points (0-72h). Image shows ERα, aromatase (CYP-19) and 18s ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as loading control. (B) Effect of ENT in Presence or Absence of Estrogen or Δ4A and Letrozole on the mRNA Expression of pS2, PgR and Aromatase in MDA-MB-231 Cells: RT-PCR analysis shows pS2, PgR and aromatase (CYP-19) with 18s ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as loading control. (C) Effect of ENT on Aromatase Activity: MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with ENT with or without fulvestrant for 18h and then assayed for aromatase activity with (ENT⇒ Letrozole) or without letrozole (*p=0.006 versus control). (D) Effect of Combining Letrozole with ENT or SAHA in MDA-MB-231 Cells. Cell viability was measured by MTT assay after 6-day treatment with increasing concentrations of letrozole alone (IC50>10μM) or in presence of ENT (100nM). IC50 value for letrozole was 6.17nM when combined with ENT (100nM). (E) Effect of Δ4A on Response of MDA-MB-231 Cells to ENT. MTT assay was performed after 6-day treatment with ENT alone, or in the presence of aromatizable Δ4A (10nM) (F) Response of ER-positive or ER-negative cells to Δ4A with or without ENT Pre-treatment. MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with ENT (1nM) or vehicle for 3 days and then with Δ4A for 3 days. MCF-7Ca cells were treated with Δ4A for 6 days. Cell viability was measured after 6 days using MTT assay.

To demonstrate that ERα was functional, a competitive binding study was performed to quantitate the ERα in MDA-MB-231 cells with or without pre-treatment with ENT. In absence of ENT treatment, E2 did not bind to the ER. When pre-treated with 1μM of ENT for 24 hours (Supplemental Figure-2), receptor sites occupied by E2 were 1123 fmoles/mg of protein (Bmax).

Next, we evaluated the effect of ENT on estrogen signaling. ENT treatment alone did not change the mRNA levels of pS2, an ERα-induced gene. However, when ENT was followed by treatment with estrogen or Δ4A for 3-hours, pS2 and PgR expression was significantly enhanced (Figure-1B). These results indicated that while functional ERα protein is expressed with ENT treatment, activation by estrogen is necessary for gene transcription. Furthermore, enhanced transcription of pS2 could be inhibited by letrozole (Figure-1B).

The basal level of aromatase activity in MDA-MB-231 cells was 5.83 ± 1.1 fmoles/μg protein/h. When cells were treated with ENT (1μM) for 24h and then incubated with [1β-3H]-Δ4A for 18hr, aromatase activity was increased to 87 ± 4.4 fmoles/μg protein/h (Figure-1C). This increase in aromatase activity was dose dependent (data not shown) and demonstrated an increase in functional enzyme. Treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with SAHA (1μM for 18 hr) also increased aromatase activity (data not shown), which could then be inhibited by letrozole (1μM). This increase in aromatase was not dependent on ERα. When cells were pre-treated with ERα downregulator fulvestrant (Ful) along with ENT, the increase in the aromatase caused by ENT was not affected (Figure-1C). Thus, these results clearly provided evidence of re-expression of both functional ERα and aromatase following ENT treatment.

As expected, the proliferation of ER-negative MDA-MB-231 cells was not affected by letrozole treatment alone. However, when combined with ENT or SAHA (100 nM), letrozole inhibited cell growth in a dose-dependent manner (IC50=6.17 nM) (Figure-1D). Inhibitory effects similar to those observed with letrozole were also seen upon combining ENT with other AIs such as anastrozole and exemestane (data not shown).

Although cell growth was inhibited by HDAC inhibitor ENT (IC50=85.4 nM) in a steroid depleted medium, in presence of E2 or Δ4A cell growth was stimulated (IC50=2.8μM) due to activation of ERα when the ligand was provided. This counteracted the growth inhibition effect of ENT alone. Thus, the dose response curve shifted to the right upon addition of Δ4A (10nM) to the treatment medium (Figure-1E). Growth stimulation was also seen when MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with ENT for 3 days and then treated with Δ4A at various concentrations. Δ4A caused mitogenic effects, suggesting that the estrogen produced by aromatase counteracted the inhibition due to ENT alone. A similar growth pattern is seen with ER-positive MCF-7Ca cells and Δ4A (Figure-1F) (8, 13).

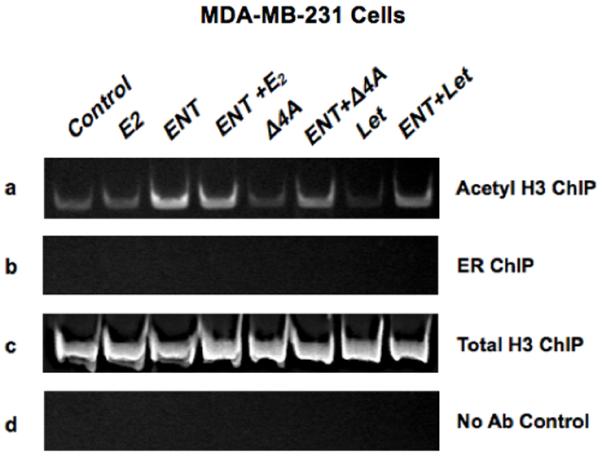

Mechanism of upregulation of aromatase

In vitro ChIP assay was used to determine whether the aromatase gene was activated in ERα dependent or independent manner. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with or without ENT for 24 hours followed by E2/Δ4A/letrozole for 3 hours. The cells were fixed and chromatin fragments were precipitated with acetyl histone H3 (Figure-2a) or ERα antibody (Figure-2b). Total histone H3 (Figure-2c) served as positive control and no antibody was included in the negative control (Figure-2d). Treatment with ENT induced transcriptional activation of aromatase promoter, as evidenced by increased recruitment of acetyl histone H3. This recruitment was not affected by treatment with E2, Δ4A or letrozole. In addition, ERα was not recruited at the aromatase promoter; consistent with the above finding that blocking ER with ER-downregulator did not affect the ENT induced increase in aromatase. These results suggest that ENT activates aromatase in an ERα independent and ligand independent manner.

Figure-2. ChIP Assay.

Association of (a) acetyl histone H3 (b) ERα (c) total histone H3 or (d) negative control (no antibody) with the aromatase PI.3/II promoter. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with indicated agents. Lane-1) control, 2) E2 (10nM), 3) ENT (1μM), 4) ENT+E2 5) Δ4 A (100nM), 6) ENT plus Δ4A, 7) Δ4A plus letrozole (1μM) and 8) ENT plus Δ4A plus letrozole.

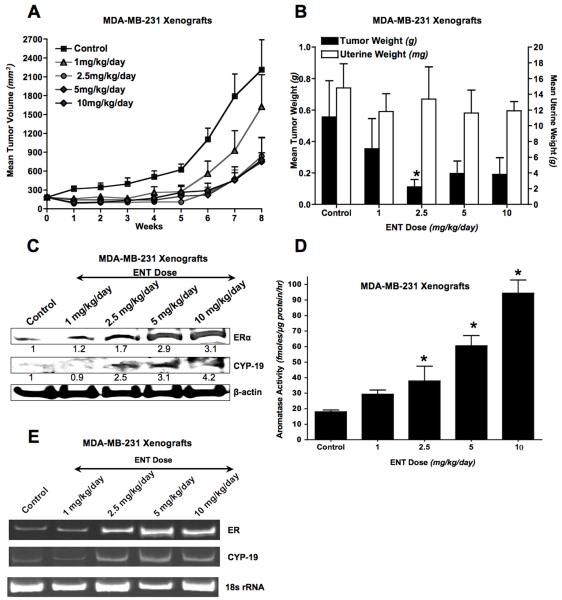

HDACi ENT converts ERα-negative breast cancers to ERα-positive tumors in vivo

In the first experiment, mice bearing MDA-MB-231 ER-negative tumors (n=5) were treated with vehicle (control) or 4 doses of ENT (1, 2.5, 5, 10 mg/kg/day) per oral (po). Tumors grew slowly in the first 5 weeks of ENT treatment, but grew rapidly thereafter (Figure-3A). The mean tumor weight of the mice treated with 2.5 mg/kg/day of ENT was significantly lower than vehicle control (*p<0.05) (Figure-3B). Although mean volumes were reduced at other doses, due to the variation in the tumor weights, the values of the mean tumor weights were not significantly different from control. Since the mouse uterus is extremely sensitive to estrogen stimulation, changes in uterine weight are useful in monitoring estrogen effects in vivo (16-18). As previously shown, AIs block estrogen production and reduce uterine weight (19-23). While ENT at 2.5mg/kg/day inhibited tumor growth, it had no effect on the estrogen sensitive mouse uterus (Figure-3B).

Figure-3.

(A) Effect of ENT on the Growth of MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: MDA-MB-231 xenografts were grown in OVX athymic nude mice. Mice were treated with increasing doses of ENT and tumor volumes were plotted versus time (B) Effect of Doses of ENT on Tumor and Uterine Weights of Mice with MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: Tumor (left y-axis) and uterine (right y-axis) weights were measured at autopsy of above mice in 3A (C) Effect of Doses of ENT on ERα and Aromatase Protein Expression in MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: Western analysis of lysates of tumors from above mice in Fig 3A; from: Lane-1) vehicle treated control, 2) ENT (1mg/kg/day), 3) ENT (2.5mg/kg/day), 4) ENT (5mg/kg/day) and 5) ENT (10mg/kg/day). Blots show ERα, aromatase (CYP-19) and β-actin (D) Effect of Doses of ENT on Aromatase Activity of Mice with MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: Aromatase activity was measured by 3H2O release assay and corrected for total protein concentration (*p<0.05 versus control) (E) Effect of Doses of ENT on the mRNA Expression of ERα, pS2 and Aromatase in MDA-MB-231 xenografts: Expression of mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR. Lane-1) control, 2) ENT (1mg/kg/day), 3) ENT (2.5mg/kg/day), 4) ENT (5mg/kg/day), and 5) ENT (10mg/kg/day). A representative gel image shows ERα and aromatase (CYP-19) and 18s ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as loading control.

The tumors collected at the end of treatment were analyzed for treatment-induced changes in target gene expression. Western blotting analysis of tumor lysates showed that treatment with ENT resulted in a dose-dependent increase in ERα and aromatase protein levels (Figure-3C) as well as activity (Figure-3D). RT-PCR confirmed transcriptional upregulation of ERα and aromatase mRNA in ENT-treated tumors (Figure-3E).

In a second experiment, groups of MDA-MB-231 tumor bearing mice were treated with ENT alone, supplemented with Δ4A or administered both ENT and Δ4A (Figure-4A). The differences in the tumor growth rate and tumor weights among the groups were not statistically significant, although values for the ENT group tended to be lower (Figure-4A,B). However, when Δ4A, which is converted to E2 by aromatase, was combined with ENT tumor growth was less inhibited. This may be explained by E2 activating ERα and stimulating the tumor growth. This increased growth effect is clearly seen in the estrogen sensitive uteri of animals given ENT + Δ4A (Figure-4B) compared to those of control mice (p<0.01) and those treated with ENT alone (p<0.05). Thus, although ENT alone increases ER and aromatase activity, there was no evidence of stimulatory effects on the uteri of these animals but only on the uteri of mice receiving ENT and estrogen (Δ4A) (Figure-4B).

Figure-4.

(A) Effect of ENT Alone or with Δ4A on the Growth of MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: MDA-MB-231 xenografts were grown in OVX nude mice and treated with vehicle, Δ4A (100μg/day), ENT (2.5mg/kg/day) or ENT plus Δ4A. The growth rates were not significantly different across the four treatment groups (B) Effect of ENT Alone or with Δ4A on the Tumor and Uterine Weights of Mice Bearing MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: Tumor (left y-axis) and uterine (right y-axis) weights were measured at autopsy of above mice in 4A (C) Effect of ENT Alone or with Δ4A Supplement on the mRNA Expression of PgR and pS2 in MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: RT-PCR analysis. Lane-1) control, 2) Δ4A (100 μg/day), 3) ENT (2.5 mg/kg/day), 4) ENT plus Δ4A, 5) Δ4A plus letrozole (10μg/day) and 6) ENT plus Δ4A plus letrozole. A representative gel image shows ERα and aromatase (CYP-19) and 18s ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as loading control.

In tumors, the mRNA levels of estrogen-regulated genes, pS2 and PgR, were higher in those treated with ENT plus Δ4A (Figure-4C). These results strongly support our findings that protein levels of ERα and aromatase in the tumors were upregulated by ENT (Figure-3C, 3E). Activation of ERα by estrogen (converted from Δ4A) induced transcription of pS2 and PgR. Consistent with these results, treatment with letrozole inhibited transcription of pS2 and PgR (Figure-4C). Collectively, these results suggest that ENT converted triple negative MDA-MB-231 xenografts into ER-positive and hormone responsive tumors.

Combining ENT with AI letrozole inhibits tumor growth in vivo

Mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts (~150 mm3) were assigned to four groups; control (vehicle), ENT (2.5 mg/kg/day) po, letrozole (10μg/day) or ENT plus letrozole. Except for the control group, all the mice received Δ4A supplement. The mean tumor volume on day 0 was not statistically different across groups (p=0.88). As shown in Figure-5A, the ENT plus letrozole markedly inhibited tumor growth compared to the control (p=0.004), ENT (p=0.009) or letrozole (p=0.049) groups. At autopsy, the mean tumor weight of mice treated with ENT plus letrozole was significantly lower than the control (p<0.001), ENT or letrozole groups (p<0.01) (Figure-5B). These results suggest that aromatase activity induced by ENT was blocked by letrozole resulting in little or no estrogen production as confirmed by reduction in uterine weight (Figure-5B). This resulted in almost complete inhibition of tumor growth.

Figure-5.

(A) Effect of ENT alone or in Combination with Letrozole on the Growth of MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: The mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts were treated with ENT alone or in combination with letrozole. Tumor volumes were measured twice a week. Tumor growth rate of the mice in the combination group was significantly lower than control (p=0.004), single agent ENT (p=0.009) or letrozole (p=0.049) (B) Effect of ENT Alone or in Combination with Letrozole on the Tumor and Uterine Weights: The tumors and uteri were collected and weighed at autopsy on day 53 of above mice in 5A. Tumor (left y-axis) and uterine (right y-axis) weights (C) Effect of ENT and Letrozole Alone or in Combination on the Protein Expression in MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: Tumors from of above mice in 5A were analyzed by western blotting. Blots show ERα, aromatase (CYP-19) and β-actin (D) Effect of ENT alone or in Combination with Letrozole on the Aromatase activity of MDA-MB-231 Xenografts: The aromatase activity in the tumors from mice above in 5A, treated with ENT is significantly higher (*a p<0.001) than control, letrozole or ENT plus letrozole. The aromatase activity was significantly lower in letrozole or ENT plus letrozole group than ENT alone († p<0.001).

Western blot analysis of the MDA-MB-231 tumors confirmed that in ENT-treated tumors, protein expression of ERα, PgR and aromatase was upregulated (Figure-5C). The tumors of mice treated with ENT plus letrozole had increased levels of aromatase protein compared to controls and ERα/PgR levels were higher than with letrozole alone. Furthermore, ENT treatment significantly increased intratumoral aromatase activity in comparison to controls (p<0.0001), which was markedly inhibited by treatment with ENT plus letrozole compared to ENT alone (Figure-5D). Similar responses were also seen in tumors of a second ER-negative cell line, Hs578T (Figure-6) and in LTLT-Ca cells (7, 12, 24) (Supplemental Figure-3). Tumors of mice treated with ENT plus letrozole had significantly smaller tumors (**p<0.001) compared to control, ENT +Δ4A and Δ4A+ letrozole groups (Figure 5).

Figure-6. Effect of ENT with or without Letrozole on the Growth of Hs578T Xenografts.

Xenografts of Hs578T cells were grown in ovariectomized female nude mice. Mice were treated as indicated. Each data point represents volume of one tumor. Tumor growth was significantly slower in the tumors of mice treated with ENT + letrozole (**p<0.01) compared to control, ENT+Δ4A and Δ4A+letrozole.

IHC analysis of treated tumors

Histopathological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the MDA-MB-2331 tumors (Supplemental Figure-4) revealed a highly necrotic center in the tumors from the ENT plus letrozole treated mice, confirming the effectiveness of the combination treatment on the growth of the tumors. Further, IHC analysis revealed that ERα was expressed in the epithelial cells (Supplemental Figure-4). These results confirmed previous findings that ENT treatment results in expression of ERα, rendering the MDA-MB-231 cells and tumors responsive to growth inhibitory effects of letrozole. In fact, tumors treated with the combination had fewer cells that stained positive for the proliferation marker, Ki67, than the control tumors (Supplemental Figure-4).

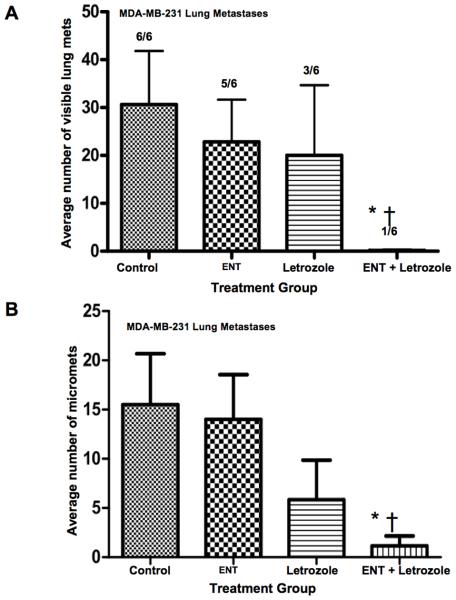

Combination of ENT plus letrozole inhibits lung colonization in metastasis model

To test the efficacy of this combination in preventing the outgrowth of tumor foci in the lung as a model for metastasis, mice were injected with MDA-MB-231 cells via the tail vein. Colonization of cells into the lungs resulted in visible or microscopic tumor foci (Figure-7A,B). All 6 of 6 mice in the control group showed an average of 60 visible metastases and 15 micrometastases per animal. Five out of 6 mice in the ENT group had visible metastases (~25 on average) and micrometastases (~13). Three out of 6 mice in the letrozole group had visible metastases (~20) and micrometastases (~7). In contrast, only one of 6 mice treated with ENT + letrozole showed one visible and 2 micrometastases in the lungs. These results provide strong evidence that the combination of ENT plus letrozole markedly inhibits growth of tumor foci in the lungs.

Figure-7. Effect of Treatment with ENT and Letrozole Alone or in Combination on Colonization of MDA-MB-231 Cells in the Lungs of Mice.

MDA-MB-231 cells were injected into the tail vein. The mice were treated with after 3 weeks with vehicle, ENT+Δ4A, Δ4A+ letrozole or combination for 6 weeks. Visible or micrometastatic foci were quantitiated at autopsy. (A) The combination of ENT (ENT) plus letrozole produced significantly fewer visible lung foci compared to control (*p=0.002) and ENT (†p=0.02). (B) Mice treated with a combination of ENT plus letrozole had significantly fewer micrometastases compared to control (*p=0.0269) and ENT (†p=0.038).

Discussion

ERα-negative breast cancers remain difficult to manage and treatment options are limited to chemotherapy since the tumors are more aggressive and resistant to endocrine therapy. Genetic alternations such as mutations, loss of heterozygosity or homozygous deletions are rare (6, 25). Studies performed by Davidson and colleagues suggested that the loss of ERα protein expression is the result of the hypermethylation of the CpG islands within the ERα promoter (5, 26). Deacetylated histones were associated with the inactive ERα promoter in MDA-MB-231 cells, whereas acetylated histones were associated with the active ERα promoter in MCF-7 cells (25). Treatment with HDAC inhibitors reversed repression of ERα in MDA-MB-231 cells (27). In this paper, we show that the HDACi, ENT was effective in causing expression of ERα and aromatase, the enzyme that is key in the production of estrogen. Targeting the upregulated aromatase using letrozole caused reduced cell viability in vitro and tumor regression in vivo. Our studies investigated both biochemical and biological consequences of these treatments and provide a strong rationale for use of AIs in combination with HDAC inhibitors for the treatment of ER-negative breast cancers.

Several studies have now confirmed that gene silencing by methylation involves generation of inactive chromatin structure, characterized by deacetylated histones (4, 26, 27). The HDACs deacetylate lysine groups of histones H3 and H4, allowing ionic interactions between positively charged lysine residues on histones and negatively charged DNA. This results in compaction of the nucleosomes, which prevents transcription (3, 4). An endogenous interaction exists between HDAC 1 and ERα in the absence of estrogen in breast cancer cells (28). HDAC 2 and 3 have been indicated to associate with ERα-regulated genes such as c-Myc and Cathepsin D (27). ENT was used in this study due to its specificity for class I HDACs such as HDAC 1, 2 and 3. ENT also exhibited a long half-life (~100 hrs) and favorable pharmacodynamic effects in humans (29, 30).

Our novel findings show that HDACi ENT can lead to an increase in functional tumoral aromatase activity and an increase in ERα mediated transcription (pS2 upregulation), both in vitro and in vivo. Our previous study with letrozole resistant LTLT-Ca cells showed that upregulation of ERα led to activation of aromatase gene transcription in a ligand dependent manner (24). However, in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with ENT, aromatase was upregulated in ERα independent manner.

Among the three HDAC inhibitors tested, ENT, SAHA and butyric acid, ENT was the most potent. These effects were not specific to just one cell line, MDA-MB-231. In vitro studies with two-other ERα-negative cell lines (SKBr-3 and Hs578T) confirmed the results obtained with MDA-MB-231. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that treatment with an HDAC inhibitor would convert ER-negative tumors to ER-positive tumors thereby rendering them sensitive to estrogens, and consequently, the inhibitory effects of AIs. Treatment of xenografts with MDA-MB-231 (Figure-5A) and HS578T tumors (Figure-6) confirmed this hypothesis. In initial dose finding studies, reduction in tumor growth was observed in ovariectomized mice treated with ENT alone (Figure-3A). However, when the mice were supplemented with Δ4A to produce estrogen, tumor growth was slightly stimulated thus negating the inhibitory effect of ENT.

The induction of aromatase in the tumor leads to the production of estrogen via aromatization of Δ4A. This results in the activation of ERα and transcription of ERα regulated genes, leading to tumor growth, thereby counteracting the tumor inhibitory effect of ENT (Figure-1E, F and 3A). In this setting, combining the AI, letrozole with ENT inhibited production of estrogen. This resulted in inhibition of tumor growth and lung metastases.

ERα -positive cancer cell lines respond to HDACi differently. In these cells, in contrast to our findings in ERα-negative cell lines, Chen et al have shown that the HDACi, LBH589, specifically inhibits aromatase activity and downregulates gene and protein expression through suppression of promoters I.3/PII (31). SAHA acts in a similar manner in MCF-7 and BT-474 cells (32). SAHA down-regulates ERα through hyperacetylation of HSP-90, a chaperone protein that maintains the stability of ERα (32). HDAC6 is HSP90 deacetylase and inhibition of HDAC6 is responsible for HDACi-mediated HSP90 inhibition (33, 34). This complex regulation of ERα by HDACi in ER-positive versus ER-negative breast cancer warrants further investigation. There is also some evidence of partial restoration of functional ERα in cells that have lost ERα and PgR expression as result of acquired resistance to endocrine therapy (35, 36). In this model system, expression of PgR could not be restored with re-expression of ERα.

The detailed molecular mechanism of the conversion of MDA-MB-231 cells from hormone-independent to hormone-dependent cells expressing ER and aromatase is unknown at this time. However, it suggests phenotypic plasticity of the cells (37, 38) that enables them to adapt (11-13, 24) to changes in their microenvironment. Further studies are needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

In conclusion, our study using both biological and biochemical assays demonstrates that HDAC inhibitor ENT increases both ERα and aromatase expression and activity, thereby converting ER-negative tumors to ERα-positive tumors. The breast cells are now sensitive to the growth stimulatory effects of estrogens synthesized locally by the aromatization of Δ4A in the tumor. Thus, when AI, letrozole, was combined with the HDAC inhibitor, the ERα expressing tumors were deprived of estrogen. This resulted in suppression of tumor growth. Furthermore, the combination treatment was also effective in inhibiting tumor cell colonization in the lungs. This novel approach could potentially provide a new treatment strategy for the management of ERα-negative breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants to A. Brodie (CA-62483 from NCI/NIH) and to A. Brodie and S. Sukumar (DOD-Center of Excellence USAMRMC W81XWH-04-1-0595; PI-S. Sukumar).

Abbreviations used

- ER

Estrogen Receptor

- Δ4A

Androstenedione

- AIs

aromatase inhibitors

- CYP-19

aromatase

- HDACi

Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

- Let

Letrozole

- ENT

entinostat

- Ful

Fulvestrant

- E2

17β-Estradiol

- Δ4A

3,17-Androstenedione

Footnotes

Note: Syndax Pharmaceuticals (MA, USA) provided entinostat and letrozole used in this study. This work was also presented in part at the 31st Annual AACR-SABCS Meeting, San Antonio, TX, December 2009.

References

- 1.Goss PE, Muss HB, Ingle JN, Whelan TJ, Wu M. Extended adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer: current status and future directions. Clinical breast cancer. 2008;8(5):411–7. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swain SM. Aromatase inhibitors--a triumph of translational oncology. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(26):2807–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giacinti L, Claudio PP, Lopez M, Giordano A. Epigenetic information and estrogen receptor alpha expression in breast cancer. The oncologist. 2006;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, Ferguson AT, Nass SJ, et al. Transcriptional activation of estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer cells by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):6890–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottaviano YL, Issa JP, Parl FF, et al. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene CpG island marks loss of estrogen receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54(10):2552–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X, Phillips DL, Ferguson AT, et al. Synergistic activation of functional estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha by DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibition in human ER-alpha-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(19):7025–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabnis G, Goloubeva O, Gilani R, Macedo L, Brodie A. Sensitivity to the aromatase inhibitor letrozole is prolonged after a “break” in treatment. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2010;9(1):46–56. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabnis G, Schayowitz A, Goloubeva O, Macedo L, Brodie A. Trastuzumab Reverses Letrozole Resistance and Amplifies the Sensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to Estrogen. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1416–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabnis G, Goloubeva O, Jelovac D, Schayowitz A, Brodie A. Inhibition of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway Improves Response of Long-term Estrogen-Deprived Breast Cancer Xenografts to Antiestrogens. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(9):2751–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabnis GJ, Macedo L, Goloubeva O, et al. Toremifene-atamestane; alone or in combination: predictions from the preclinical intratumoral aromatase model. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;108(1-2):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabnis GJ, Macedo LF, Goloubeva O, Schayowitz A, Brodie AM. Stopping treatment can reverse acquired resistance to letrozole. Cancer Res. 2008;68(12):4518–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jelovac D, Sabnis G, Long BJ, et al. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in xenografts and cells during prolonged treatment with aromatase inhibitor letrozole. Cancer Res. 2005;65(12):5380–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabnis GJ, Jelovac D, Long B, Brodie A. The role of growth factor receptor pathways in human breast cancer cells adapted to long-term estrogen deprivation. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3903–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long BJ, Tilghman SL, Yue W, et al. The steroidal antiestrogen ICI 182,780 is an inhibitor of cellular aromatase activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;67(4):293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazi AA, Jones JM, Koos RD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis of gene expression in the rat uterus in vivo: estrogen-induced recruitment of both estrogen receptor alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 to the vascular endothelial growth factor promoter. Molecular endocrinology. 2005;19(8):2006–19. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langston WC, Robinson BL. Castration atrophy. A chronological study of uterine changes following bilateral ovariectomy in the albino rat. Endocrinology. 1935;19:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens JW, Ashby J. Critical review and evaluation of the uterotrophic bioassay for the identification of possible estrogen agonists and antagonists: in support of the validation of the OECD uterotrophic protocols for the laboratory rodent. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Critical reviews in toxicology. 2002;32(6):445–520. doi: 10.1080/20024091064291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens SM, Moley KH. Follicular origins of modern reproductive endocrinology. American journal of physiology. 2009;297(6):E1235–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00575.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brodie A, Lu Q, Yue W, Wang J, Liu Y. Intratumoral aromatase model: the effects of letrozole (CGS 20267) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;49(Suppl 1):S23–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1006028202087. discussion S33-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jelovac D, Macedo L, Handratta V, et al. Effects of exemestane and tamoxifen in a postmenopausal breast cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(21):7375–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long BJ, Jelovac D, Thiantanawat A, Brodie AM. The effect of second-line antiestrogen therapy on breast tumor growth after first-line treatment with the aromatase inhibitor letrozole: long-term studies using the intratumoral aromatase postmenopausal breast cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2378–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu Q, Yue W, Wang J, et al. The effects of aromatase inhibitors and antiestrogens in the nude mouse model. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;50(1):63–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1006004930930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunez NP, Jelovac D, Macedo L, et al. Effects of the antiestrogen tamoxifen and the aromatase inhibitor letrozole on serum hormones and bone characteristics in a preclinical tumor model for breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(16):5375–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabnis G, Schayowitz A, Goloubeva O, Macedo L, Brodie A. Trastuzumab reverses letrozole resistance and amplifies the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to estrogen. Cancer Res. 2009;69(4):1416–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weigel RJ, deConinck EC. Transcriptional control of estrogen receptor in estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53(15):3472–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma D, Blum J, Yang X, et al. Release of methyl CpG binding proteins and histone deacetylase 1 from the Estrogen receptor alpha (ER) promoter upon reactivation in ER-negative human breast cancer cells. Molecular endocrinology (Baltimore, Md. 2005;19(7):1740–51. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma D, Saxena NK, Davidson NE, Vertino PM. Restoration of tamoxifen sensitivity in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells: tamoxifen-bound reactivated ER recruits distinctive corepressor complexes. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6370–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai H, Li H, Avraham S, Jiang S, Avraham HK. Overexpression of histone deacetylase HDAC1 modulates breast cancer progression by negative regulation of estrogen receptor alpha. International journal of cancer. 2003;107(3):353–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gore L, Rothenberg ML, O’Bryant CL, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor, MS-275, in patients with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(14):4517–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kummar S, Gutierrez M, Gardner ER, et al. Phase I trial of MS-275, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, administered weekly in refractory solid tumors and lymphoid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1):5411–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen S, Ye J, Kijima I, Evans D. The HDAC inhibitor LBH589 (panobinostat) is an inhibitory modulator of aromatase gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(24):11032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000917107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiskus W, Ren Y, Mohapatra A, et al. Hydroxamic acid analogue histone deacetylase inhibitors attenuate estrogen receptor-alpha levels and transcriptional activity: a result of hyperacetylation and inhibition of chaperone function of heat shock protein 90. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(16):4882–90. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bali P, Pranpat M, Bradner J, et al. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(29):26729–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovacs JJ, Murphy PJ, Gaillard S, et al. HDAC6 regulates Hsp90 acetylation and chaperone-dependent activation of glucocorticoid receptor. Molecular cell. 2005;18(5):601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oesterreich S, Zhang P, Guler RL, et al. Re-expression of estrogen receptor alpha in estrogen receptor alpha-negative MCF-7 cells restores both estrogen and insulin-like growth factor-mediated signaling and growth. Cancer Res. 2001;61(15):5771–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pathiraja TN, Stearns V, Oesterreich S. Epigenetic regulation in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer--role in treatment response. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2010;15(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10911-010-9166-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature. 2007;447(7143):433–40. doi: 10.1038/nature05919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prindull G, Zipori D. Environmental guidance of normal and tumor cell plasticity: epithelial mesenchymal transitions as a paradigm. Blood. 2004;103(8):2892–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.