Abstract

One of several challenges in design of clinical chemoprevention trials is the selection of the dose, formulation and dose schedule of the intervention agent. Therefore, a cross-over clinical trial was undertaken to compare the bioavailability and tolerability of sulforaphane from two of broccoli sprout-derived beverages: one glucoraphanin-rich (GRR) and the other sulforaphane-rich (SFR). Sulforaphane was generated from glucoraphanin contained in GRR by gut microflora or formed by treatment of GRR with myrosinase from daikon (Raphanus sativus) sprouts to provide SFR. Fifty healthy, eligible participants were requested to refrain from crucifer consumption and randomized into two treatment arms. The study design was as follows: 5-day run-in period, 7-day administration of beverages, 5-day washout period, and 7-day administration of the opposite intervention. Isotope dilution mass spectrometry was used to measure levels of glucoraphanin, sulforaphane and sulforaphane thiol conjugates in urine samples collected daily throughout the study. Bioavailability, as measured by urinary excretion of sulforaphane and its metabolites (in approximately 12 hour collections after dosing), was substantially greater with the SFR (mean = 70%) than with GRR (mean = 5%) beverages. Interindividual variability in excretion was considerably lower with SFR than GRR beverage. Elimination rates were considerably slower with GRR allowing for achievement of steady state dosing as opposed to bolus dosing with SFR. Optimal dosing formulations in future studies should consider blends of sulforaphane and glucoraphanin as SFR and GRR mixtures to achieve peak concentrations for activation of some targets and prolonged inhibition of others implicated in the protective actions of sulforaphane.

Keywords: sulforaphane, glucoraphanin, broccoli sprouts, clinical trial

Introduction

Developing rational chemoprevention strategies requires well-characterized agents, suitable cohorts and reliable intermediate biomarkers of cancer or cancer risk (1). Sulforaphane is one promising agent under preclinical and clinical evaluation. Sulforaphane was isolated from broccoli guided by bioassays for the induction of the cytoprotective enzyme NQO1 (2). The inducible expression of NQO1 is now recognized to be regulated principally through the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway (3). This pathway in turn is an important modifier of susceptibility to electrophilic and oxidative stresses; factors central to the processes of chemical carcinogenesis and other chronic degenerative diseases (4). Sulforaphane is an extremely potent inducer of Nrf2 signaling and blocks the formation of dimethylbenz[a] anthracene-evoked mammary tumors in rats as well as other tumors in various animal models (5, 6). In some instances, these protective effects are lost in Nrf2-disrupted mice (7, 8). In addition to increasing cellular capacity for detoxifying electrophiles and oxidants, sulforaphane has been shown to induce apoptosis, inhibit cell cycle progression and inhibit angiogenesis (9, 10). Collectively, these actions serve to impede tumor growth. Because of the potent and multimodal actions of sulforaphane, this agent continues to be evaluated in the context of preventive and therapeutic settings in individuals at risk for neoplasia. In large part due to its antioxidative actions, sulforaphane is also under clinical evaluation in settings where oxidative stress plays important roles in etiopathogenesis; namely, pulmonary diseases such as asthma and COPD, cardiovascular disease and protection against radiation damage. A current search of ClinicalTrials.gov indicates nearly a score of trials evaluating sulforaphane-rich preparations, principally administered in the forms of mature broccoli or broccoli sprout extracts. But it is unclear whether intact vegetables, vegetable extracts or preparations, or the pure compound or its biogenic precursor lacking the matrix constituents are optimal for chemoprevention.

Broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables (e.g., cabbage, kale, and Brussels sprouts) are widely consumed in many parts of the world. Epidemiological evidence from prospective cohort studies and retrospective case-control studies suggest that consumption of a diet rich in crucifers reduces the risk of several types of cancers as well as some chronic degenerative diseases (11–13). There is growing evidence that the protective effects of crucifers against disease may be attributable largely to their content of glucosinolates (β-thioglucose N-hydroxysulfates) (14). Glucosinolates in plant cells are hydrolyzed to bioactive isothiocyanates by the β-thioglucosidase myrosinase (14). Myrosinase is released from intracellular vesicles following crushing of the plant cells by chewing or food preparation. This hydrolysis is also mediated in a less predictable manner by β-thioglucosidases in the microflora of the human gut (15). Young broccoli plants are an especially good source of glucosinolates, with levels 20–50 times those found in mature market-stage broccoli (16). The principal glucosinolate contained in broccoli is glucoraphanin, which is hydrolyzed by myrosinase to sulforaphane.

Qidong, People’s Republic of China is a region where exposures to foodborne and airborne toxins and carcinogens can be considerable and approaches to chemoprevention are needed. Hepatocellular carcinoma can account for up to 10% of the adult deaths in some rural townships in the Qidong region. Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus, coupled with exposure to aflatoxins in the diet, likely contributes to this high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (17). The extent of aflatoxin contamination in foods is not completely preventable such that chemoprevention may be especially useful in the setting of ongoing aflatoxin exposure and prior infection with hepatitis B virus. We have previously conducted randomized, placebo-controlled intervention trials with oltipraz (18), chlorophyllin (19) and most recently, glucosinolate-rich broccoli sprouts (20) with residents of Qidong in a continuing effort to identify an agent with the desired properties of efficacy, tolerability, practicality of use including cultural acceptability, and low cost. Broccoli sprout preparations perhaps best embody these features, but there is limited information on optimal doses, schedules or formulations for their use in chemoprevention. In our initial intervention with a glucosinolate-rich beverage in Qidong, an inverse association was observed for excretion of sulforaphane and its metabolites and aflatoxin-DNA adducts in individuals randomized to receiving broccoli sprouts glucosinolates (20). Moreover, trans, anti-phenanthrene tetraol, a metabolite of the combustion product phenanthrene, was detected in the urine of all participants and also showed a robust inverse association with sulforaphane excretion. However, overall differences in biomarker levels between treatment and placebo arms were modest, perhaps reflecting unexpectedly high interindividual variation in the hydrolysis of glucoraphanin and/or in the uptake, metabolism and elimination of its cognate isothiocyanate sulforaphane.

With the variability in the sources, contents, and formulations as well as doses and schedules of broccoli and broccoli preparations used in current clinical trials, it is important to understand the key factors influencing their kinetics and dynamic actions in humans in order to optimize efficacy. Therefore, a simple cross-over design trial was conducted with 50 participants to evaluate and compare the bioavailability of sulforaphane from broccoli sprouts in two forms: enterically generated from glucoraphanin by gut microflora; or pre-released by treatment of the former preparation with myrosinase from the plant Raphanus sativus.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

Adults in good general health without a history of major chronic illnesses were randomized into two intervention arms in a cross-over trial design for comparing pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of two forms of broccoli sprouts extracts: glucoraphanin-rich (GRR) and sulforaphane-rich (SFR). The study of men and women included hepatitis B surface antigen-positive individuals with normal liver function. Study participants were recruited from the villages of Yuan He and Wu Xing in the rural farming community of He Zuo Township, Qidong, Jiangsu Province, People’s Republic of China. Two hundred five individuals were screened at the village clinics over 2 days in the fall of 2009. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and the Qidong Liver Cancer Institute. A medical history, physical examination and routine hepatic and renal function tests were used to screen the individuals, aged 25 to 65 years, by methods identical to those described for previous interventions in this region (20, 21). Sixty-nine individuals from the screened group were eligible, of which the initial 50 were randomized using a fixed randomization scheme with a block size of 10. Participants returned to the clinics on the first day of the study where they provided informed consent for the intervention study and were given their identification code.

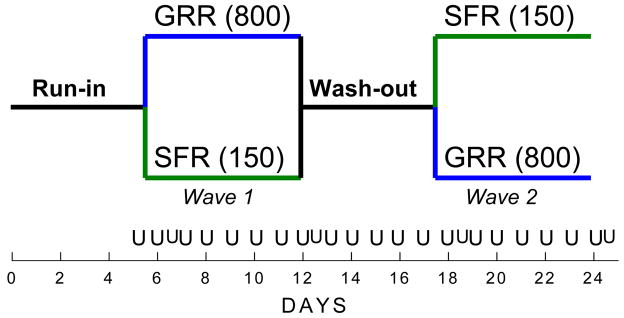

All participants were asked to refrain from eating any green vegetables that could possibly contain glucosinolates and they were thus provided a comprehensive list of food items to avoid and those that were acceptable. Participants were assigned to one of six groups of 6 to 10 individuals, based upon area of residence. Participants, local doctors and study investigators would meet at a designated home of one of the participants in each group between 5 and 6 PM for distribution of the intervention beverages and monitoring of compliance. As shown in Figure 1, participants consumed a “placebo” beverage containing mango juice during a 5-day run-in before randomization to either a GRR or a SFR beverage for the next 7 days (first wave). After an additional 5-day wash-out period, participants received the alternate broccoli-derived beverage from their first allocation for a final 7 days (second wave). Compliance was determined by visual observation of consumption and measures of urinary excretion of sulforaphane metabolites (see below). GRR and SFR beverages were prepared fresh each afternoon from bulk powders and brought to He Zuo daily for distribution. Overnight (roughly 12 h) urine samples were collected each morning, volumes measured, and aliquots prepared and transported to Qidong for initial storage at −20°C. Ascorbic acid was added to the urine collection bottles prior to distribution to participants. Blood samples were collected on the last evening of each of the 7-day active intervention waves of the study. Serum alanine aminotransferase activities were determined at the Qidong Liver Cancer Institute on all collected samples. Aliquots of urine and serum from each sample were shipped frozen to Baltimore at the end of the study, where serum samples were transferred immediately to a clinical laboratory (Hagerstown Medical Laboratory, Hagerstown, MD) for comprehensive blood chemistry analyses.

Fig 1.

Outline of the intervention protocol, schedule, and timeline. Placebo beverages were administered daily, shortly before dinner, for 5 consecutive days (“run-in”). Participants were randomized to receive either the GRR beverage containing 800 μmole glucoraphanin or the SFR beverage containing 150 μmole sulforaphane for 7 consecutive days. The placebo beverage was then administered for 5 consecutive days (“wash-out”), at which time cross-over assignments of the study beverages were consumed nightly for an additional 7 days. Overnight voids (0–12 h) were collected each morning on days 1 through 24. In addition, follow-up daytime voids (12–24 h) were collected on days 6, 12, 18, 24.

Preparation of the Broccoli Sprouts Beverages

The study was conducted using re-hydrated, previously lyophilized broccoli sprout powders rich in either glucoraphanin or sulforaphane that were produced by the Brassica Chemoprotection Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine, Department of Pharmacology, for clinical study use. Broccoli sprouts were grown from specially selected BroccoSprouts seeds (DM1999B) with technology licensed from Johns Hopkins University. Briefly, seeds were surface disinfested, and grown in a commercial sprouting facility (Sprouters Northwest, Inc., Kent, WA) under controlled light and moisture conditions. After 3 days of sprout growth, an aqueous extract was prepared in a steam jacketed kettle at a food processing facility (Oregon Freeze Dry, Albany, OR). Sprouts were plunged into boiling deionized water and allowed to boil for 30 minutes. The resulting aqueous extract contained about 5 μmol/ml of glucoraphanin, the biogenic precursor of sulforaphane.

A GRR powder was prepared by lyophilizing this aqueous extract at Oregon Freeze Dry. Total glucoraphanin titer was determined in the resulting powder by HPLC (22) to be 329 μmol/g powder when assayed just prior to use in the clinical study. To prepare a SFR powder, the aqueous extract was filtered, cooled to 37°C, and treated with myrosinase, an enzyme released from a small amount of daikon (Raphanus sativus) sprouts, for 4 hours in order to hydrolyze the glucosinolates to isothiocyanates. Isothiocyanate and sulforaphane levels were then quantified by cyclocondensation analysis (23) and by direct HPLC (22, 24), respectively. This hydrolyzed aqueous extract was also lyophilized at Oregon Freeze Dry. Sulforaphane content at time of use was 202 μmol/g powder and represented 91% of the total isothiocyanate content in the powder.

The bulk powders were tested for microbial contaminants prior to release by Oregon Freeze Dry and again upon receipt in Baltimore. Both powder preparations were stored in sealed bags in a locked, dedicated −80° freezer until reconstitution of the study beverages.

Daily allotments of each powder were dissolved in sterile water. An equal volume of mango juice (Del Monte, Lotte Chilsung Beverage Co., Seoul, Korea) was added with vigorous mixing prior to transfer of 100 mL individual doses into sterile 330 mL commercial bottled water bottles for daily distribution to study participants. The juice served to mask flavor and taste, but had no effect on the stability of the phytochemicals; nor did the juice contribute any enzyme inducer activity to the beverage (data not shown). The daily doses were 800 μmol of glucoraphanin in GRR and 150 μmol of sulforaphane in SFR beverages. The mango-water beverage without addition of any powder was administered to participants as a “placebo” during the run-in and wash-out phases of the study.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from serum by using a Qiagen QIAamp Mini Blood isolation kit. GSTM1 and GSTT1genotypes were identified by real-time PCR using an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The DNA was amplified in 25-μl reactions containing Taqman Universal Master Mix, 50 ng of genomic DNA, 500 nM forward and reverse primers, and 200 nM Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems). The probes were dye-labeled; GSTT1 with 5’-FAM and 3’-TAMRA and GSTM1 with 5’-VIC and 3’-TAMRA (Applied Biosystems) allowing for a single muliplex reaction. All PCR conditions and primer sequences were as previously reported (25).

Glucoraphanin and Sulforaphane in Urine

Measurement of sulforaphane and sulforaphane metabolites in urine was performed by a modification of a previously reported isotope dilution mass spectrometric assay as described by Egner et al. (26). Positive ESI-MS/MS was carried out using a Thermo-Finnigan TSQ Advantage triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled to a Thermo-Finnigan Accela UPLC and HTC Pal autoinjector (ThermoElectron Corporation, San Jose, CA). Briefly, chromatographic separation of analytes was achieved using a 1.9 μm 100 × 1 mm Thermo Hypersil Gold column maintained at 40°C. Urinary concentrations of glucoraphanin were also determined using the TSQ mass spectrometer operated in the negative mode. The internal standard used for isotope dilution calibration curves, [glucose-13C6]glucoraphanin, was prepared by oxidation of [glucose-13C6]glucoerucin (27) with hydrogen peroxide (28). A Thermo Aquasil C18 30 μm 150 × 1 mm column operating at a flow rate of 100 μl/min was used for chromatographic separation. Mobile phase compositions were as follows (by volume): (A) water/formic acid (100/0.1) and (B) water/acetonitrile/formic acid (50/50/0.1) The initial mobile phase composition was held at 5% B for 3 min and then ramped to 30% B over 4.5 min. The column was then re-equilibrated to initial conditions for 6.5 min. Column flow was diverted away from the electrospray source except between 2 to 5 min. Negative ESI-MS/MS was conducted with the capillary temperature set at 320°C, the sheath gas at 20 arbitrary units, and the spray voltage at 4kV. MS/MS transitions were m/z 436→372 and m/z 442→378 amu for the unlabeled glucoraphanin and [glucose-13C6]glucoraphanin, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

There were three components to the analysis: (i) treatment and time comparisons of the 12-hour excretion levels of sulforaphane and conjugates, (ii) their within-individual variances, and (iii) a comparison of their elimination kinetics by beverage type. The primary outcome of interest was total sulforaphane uptake and elimination (μmol/12 hours) over time, by treatment. Since the primary outcome was not normally distributed within- or between-individuals, medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used as the summary statistics for sulforaphane levels and ratios of levels used as measures of the putative effects of time and/or treatment. Daily percent change was calculated as an ordinary-least squares regression of each participant’s excretion of sulforaphane in the log scale on 7-day periods while on a given treatment. Stability of sulforaphane excretion while on treatment during a given 7-day period was determined by testing whether the median of the daily percent change in sulforaphane amounts were null (i.e., equal to zero). For comparisons by treatment, outcomes included the 7-day medians of the overnight excretion levels of sulforaphane plus conjugates (SFT) (μmol /12 hours) and their corresponding 7-day coefficients of variation (CV). Initial clearance was expressed as the ratio of (SFT amounts in the daytime voids: 12–24 h) to (SFT amounts of the overnight voids: 0–12 h) for days 6, 12, 18 and 24. Extended clearance was calculated as the ratio of SFT amounts in a given void divided by the levels in the preceding collection during the washout phase (days 12, 12.5, 13 to 17).

Statistical significance at the 5% level of time and/or treatment effects were determined by nonparametric methods: Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data where an individual is his/her own control and the rank-sum test for two sample comparisons (e.g., those receiving a treatment in days 6 to 12 vs. those receiving the same treatment in days 18 to 24).

Results

Enrollment and Comparability of Intervention Arms

Initially, 205 individuals were screened in order to recruit the target goal of 50 participants. These participants were then randomized into the two intervention arms, one group receiving GRR followed by SFR beverages and the second receiving SFR followed by GRR beverages, as indicated in Figure 1. Overall, there were 17 men (34%) and 33 women (66%) with a median age of 46 (range 29–62) years enrolled in the study. Following the randomization process it was determined that the intervention groups did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) by age, gender, hepatitis B surface antigen status, smoking status, or alcohol consumption. Further, for most parameters, these distributions were representative of the total screened population (data not shown).

Compliance, Data Collection Completeness and Tolerability

Adherence to the study protocol was outstanding throughout the 24 days of the intervention trial. Only two individuals dropped out of the study; one after two doses of SFR beverage during the first wave (days 5–12) and the second in the midst of the wash-out phase (days 12–17). A third participant consistently had alkaline urine which impeded the measurement of sulforaphane and consequently these data were eliminated from the kinetic analyses. With the exception of the two drop-outs, the remaining 48 participants consumed 100% of the study beverages during the intervention, as assessed by daily monitoring of intake by study investigators and analytical measurement of sulforaphane conjugates and creatinine in urine samples. Further, all blood specimens and all but one of the urine samples were collected from each participant over the duration of the trial. Only two grade one adverse events were reported by the participants; nausea or vomiting associated with the odor or ingestion of the SFR beverage, respectively. There were no abnormal clinical chemistry values for blood samples collected on the last days of the two active intervention waves (day 12 and day 24) of the study. A blinded survey of taste-preference at the end of the study indicated a strong preference (81% to 19%) amongst the participants for the beverage allocated to them as GRR compared to SFR, irrespective of whether they received it in the first or second wave. While partial masking of the sharp taste of the beverages, especially prominent with SFR, was accomplished by dissolution of the broccoli sprout powder in mango juice, study participants anecdotally noted that chewing freshly cut stalks of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, a regional crop that was being harvested at the time of the intervention) after beverage drinking attenuated any aftertaste.

Urinary Excretion of Sulforaphane and Sulforaphane Conjugates

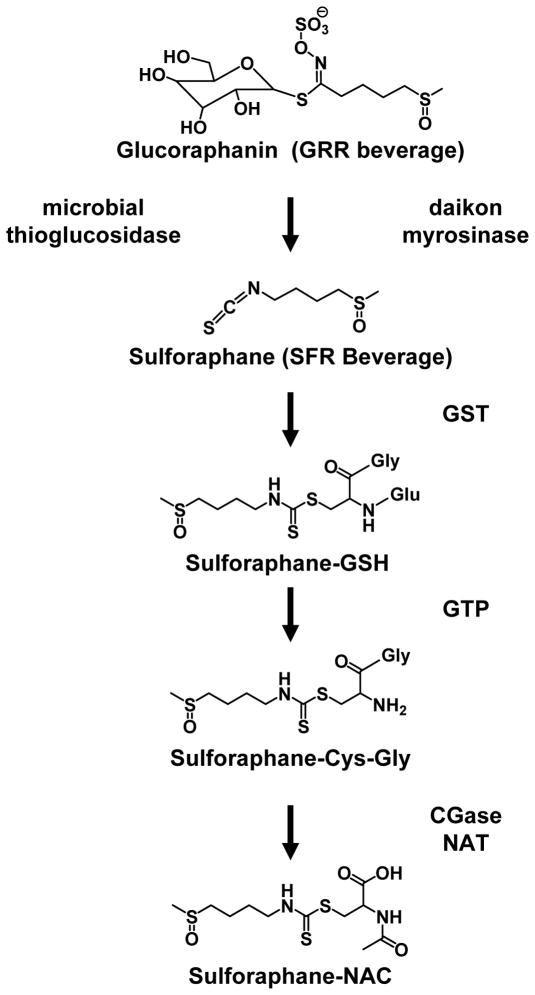

Isotope-dilution mass spectrometry was used to measure levels of glucoraphanin, sulforaphane and sulforaphane conjugates in the urine samples collected throughout the intervention. Sulforaphane (SF), sulforaphane-cysteine (SF-Cys), and sulforaphane-N-acetylcysteine (SF-NAC) were quantified in all samples collected between days 5 and 24. Pilot analyses on a subset of samples collected during a SFR wave indicated that levels of sulforaphane-glutathione (SFN-GSH) and sulforaphane-cysteinylglyeine (SF-CysGly) were substantially less than 0.1% of the total pool of excreted sulforaphane equivalents (SFT). Therefore, systematic measurements of these minor analytes were not conducted. Figure 2 depicts the pathway of conversion of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane and the subsequent metabolism of sulforaphane to its thiol conjugates.

Fig. 2.

Glucoraphanin in broccoli is converted to sulforaphane either by plant myrosinases, or if the plant myrosinases have been denatured by cooking, by bacterial myrosinases in the human colon. Sulforaphane is passively absorbed and rapidly conjugated with glutathione by glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), then metabolized sequentially by γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase (GTP), cysteinyl-glycinease (GCase) and N-acetyltransferase (NAT). The conjugates are actively transported into the systemic circulation where the merapturic acid (SF-NAC) and its precursors are urinary excretion products.. Deconjugation may also occur to yield the parent isothiocyanate, sulforaphane. For the beverages used in the intervention, sulforaphane metabolites were generated enterically from glucoraphanin through the action of thioglucosidases in the gut microflora (GRR); or pre-released by treatment of aqueous broccoli sprout extract with myrosinase from the daikon plant Raphanus sativus (SFR).

Cross-sectional statistics for SFT and its components

Figure 3 depicts SFT excreted (log scale) by each individual over the course of days 5–24. Supplemental Table 1 enumerates the complete cross-sectional statistics for sulforaphane and its conjugates and their sums at each day for the 25 individuals in each treatment arm. Data in Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 1 demonstrate that excretion of SFT increased more than 1000-fold during the SFR waves. Baseline levels were < 0.1 μmol/12 h, while median amounts excreted during the 12-hour intervals following each night of the 7-day waves (days 6–12 or 18–24) were 94 μmol and 75 μmol following each dose in the SFR → GRR and GRR→ SFR arms, respectively.

Fig.3.

Urinary levels of sulforaphane and conjugates (log scale) as determined by HPLC/isotope-dilution mass spectrometry. Lines represent excretion amounts for individual study participants with green indicating the period an individual was on SFR treatment and blue when the individual was on GRR treatment. The black portion of the lines corresponds to the pre-treatment and wash-out periods. The dots represent the medians on each day and correspond to the data presented in Supplemental Table 1 for the total sulforaphane amounts (SFT). A. GRR → SFR. B. SFR → GRR.

Time-dependent changes in SFT excretion

To determine whether there was any change in levels of excretion of SFT over the week-long dosing, an analysis was performed on each treatment arm to determine the within-individuals median daily percent change of overnight SFT. This analysis tested the null hypothesis that there was no change over these 7 days. The median and IQR of the daily percent change over 7 days by treatment arm are presented in Supplemental Table 2. The signed-rank test indicated that the daily percent change for days 6 to 12 were not significantly different from 0%, for both SFR and GRR treatment. In turn, for days 18 to 24 in both SFR and GRR treatment, there was a small, significant decline in levels over time. This decline was not readily explained by participant fatigue since there were no differences in daily urine volumes or creatinine excretion between the first and second waves. Moreover, when comparing the daily percent change from days 6 to 12 and days 18 to 24 within each treatment, there were no statistical differences (p = 0.120 for SFR and p= 0.139 for GRR). Thus, the daily excretion levels of SFT did not change with repetitive dosing of either GRR or SFR.

Effect of treatment order

Since the daily percent changes in levels over time were fairly stable, the analysis of within-individual levels for each 7-day period was simplified by describing the data using the median. Supplemental Table 3 shows summary statistics of the within-individual 7-day medians of the overnight SFT levels. The median SFT level for the arm receiving SFR treatment first (i.e., days 6 to 12) was 93.9 μmol/12 hours compared to 74.9 μmol/12 hours in the group receiving SFR treatment second (i.e., days 18 to 24). The median level for the arm receiving GRR first was 19.3 μmol/12 hours and it was 24.2 μmol/12 hours for those receiving GRR second. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test for two-samples compared whether SFT levels differ by whether a treatment (GRR or SFR) was given first or second. The rank-sum test showed a statistically significant difference in SFR treatment order (p = 0.021). In contrast, there was no significant difference in SFT levels by GRR treatment order (p = 0.202).

Comparison of SFT between GRR and SFR Treatment

To quantify the differences in SFT between treatments, within-individual ratios were calculated as the median level of SFT while on the SFR regimen divided by the median level while on the GRR regimen. The median and IQR of this variable are presented in Table 1 dichotomized for each arm separately and overall (combined arms). The signed-rank test for significance tested whether the ratios of the within-subject levels were different from 1. This median ratio indicates that SFT levels were 3.58 times higher for SFR treatment than when the same individual was treated with GRR. This ratio was 3.59 for those receiving GRR first and SFR second and 3.36 for the group receiving SFR first and GRR second. The ratios between the two waves were not statistically different (p= 0.139, results not shown), thus the overall median ratio proved to be an appropriate summary of the effect of SFR treatment on SFT levels compared to GRR treatment.

Table 1.

Ratio of amounts of SFT (SFR Treatment / GRR Treatment ratio of within-individual medians) and ratio of within-individual variability (coefficient of variation). Wilcoxon Signed-rank test for significancea.

| Treatment arm | Median of ratios of within-individual 7-day median SFT SFR Treated/GRR Treated [IQR] | Median of ratios of within-individual 7-day coefficients of variation of SFT SFR Treated/GRR Treated[IQR] |

|---|---|---|

| SFR → GRR(n=23) | 3.36 [2.05, 5.50] p< 0.001 |

0.83 [0.34, 1.00] p= 0.004 |

| GRR → SFR (n=24) | 3.59 [1.80, 7.93] p< 0.001 |

0.54 [0.28, 0.78] p< 0.001 |

| Overall (n=47) | 3.58 [2.02, 7.43] p< 0.001 |

0.61 [0.33, 0.92] p< 0.001 |

p-values for null hypothesis of median ratios being equal to 1.

Intraindividual variance

Table 1 also presents the ratio of within-individual coefficients of variation, a measure of intraindividual variance, comparing the CV during SFR treatment to the CV during GRR treatment. The median CV ratio of the overall study population shows that the within-individual CV over 7 days of SFR treatment was 0.61 times the CV of the same course of GRR treatment. There was no statistically significant difference in CV ratios between treatment waves (rank-sum test; p= 0.187). The difference in CVs between SFR and GRR was statistically different in these three comparisons; notably there was much less variance while on SFR compared to GRR.

Comparison of elimination rates of SFT between GRR and SFR

In this study protocol, each individual provided sequential 0–12 and 12–24 hour urine collections for the first and last day of each treatment wave (days 6, 12, 18 and 24). Thus, within-individual initial elimination of SFT and individual SF metabolites could be estimated and compared by treatment. Initial elimination was calculated as the ratio of SFT levels in the daytime (12–24 hour) voids to the amounts of SFT of the overnight (0–12 hour) voids (for days 6, 12, 18 and 24) and the results are shown in Table 2. Among those subjects in the arm who received SFR first, the SFT levels in the12–24 hour sample for day 6 were 0.036 times the levels of the first 12 hours after treatment; expressed differently, the SFT level during the second 12 hours after treatment was about 4% of the level observed in the first 12 hours and is indicative of very rapid clearance. The signed-rank test showed there were no within-individual differences from the first treatment day (day 6 and day 18) to the last treatment day (day 12 and 24, respectively). The overall median ratio for the SFR treatment was a summary of the change in SFT levels: the 12–24 hour levels were only 4.4% of the 0–12 hour levels. The results for GRR treatment may be interpreted in the same way. The signed-rank test showed that the initial elimination was not different between days 6 and 12 or between days 18 and 24. Overall, the SFT levels in the second 12 hours were about 41% of the level in the first 12 hours. In summary, the initial elimination of SFT while on GRR treatment was about 10 times lower in the 12-hour level urine collections than while administered SFR (0.413 vs. 0.044; p< 0.001).

Table 2.

Initial elimination rates for treatments measured by the half-day decline after days 6, 12, 18 and 24.

| Ratio of SFT | SFR Treatment Median Ratio [ IQR ] | Signed-rank Test | GRR Treatment1 Median [ IQR ] | Signed-rank Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6.5 / Day 6 (n= 25) | 0.036 [0.027, 0.076] | p= 0.978 | 0.454 [0.270, 0.923] | p= 0.357 |

| Day 12.5 / Day 12 (n= 24) | 0.042 [0.020, 0.068] | 0.323 [0.244, 0.638] | ||

| Day 18.5 / Day 18 (n= 23) | 0.048 [0.029, 0.144] | p= 0.963 | 0.326 [0.214, 0.607] | p= 0.326 |

| Day 24.5 / Day 24 (n= 23) | 0.054 [0.032, 0.108] | 0.399 [0.242, 1.138] | ||

| Overall (n=46) | 0.044 [0.031, 0.088] | 0.413 [0.270, 0.823] |

Summary model

Figure 4 depicts the pattern of the SFT levels in μmol/12 h in consonance with the statistical modeling just described. That is, (i) levels 12 hours after the administration of treatment were the same over time (from Supplemental Table 2); (ii) the proportional elimination (day X.5/day X) is 0.044 for SFR and 0.413 for GRR and is the same at all days (from Table 2). The peak (overnight) excretion amounts are the values of 93.9, 79.9, 24.2 and 19.3 μmol SFT/12 hour for SFR and GRR in waves 1 and 2, respectively (Supplemental Table 3). The points represent the median SFT amounts on each day corresponding to Supplemental Table 1 and are connected by discontinuous lines to reflect that 12–24 hour voids were not collected on most days of the study.

Fig. 4.

Modeled urinary elimination kinetics (arithmetic scale) for sulforaphane and conjugates. ●, median. A. GRR → SFR. B. SFR → GRR. See text for detailed description.

Urinary Excretion of Glucoraphanin

Glucoraphanin was only measured in the urine samples collected during the GRR treatment waves since no glucoraphanin was detectable in the SFR preparation (data not shown). Supplemental Figure 1 depicts a selected ion mass chromatogram for glucoraphanin and the [glucose-13C6]glucoraphanin in a urine sample collected from an individual receiving GRR. Background excretion levels of < 0.2 μmole glucoraphanin in 12 h were detected in urine samples at the end of the SFR waves and 24 hour after the last dose of GRR beverage. Elevated levels, typically 2–4 μmol/12 h, were detected in all samples collected as 0–12 h voids during the GRR treatment waves. As with the individual sulforaphane components and SFT, elimination of glucoraphanin was constant throughout the 7-day dosing periods with no obvious evidence of accumulation over time. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the absorption and elimination of glucoraphanin as a glucosinolate in humans, although it should be noted that these levels reflect less than 3% of the administered dose and about 10% of the excreted dose.

Influence of GST Genotype on SFT Excretion

To explore a potential role for GST genotype to modify patterns or rates of sulforaphane metabolism, all participants were genotyped for GSTM1 and GSTT1 status. As shown in Supplemental Table 4, 34% of the study participants were null for GSTM1 alleles, while 51% were null for GSTT1. These distributions are consistent with other studies of these genotypes in China (29). There was no effect of either genotype alone or both combined on the cumulative excretion of sulforaphane conjugates derived from glutathione conjugation over the 7-day dosing period in participants administered either SFR or GRR beverage.

DISCUSSION

One of several challenges in design of clinical chemoprevention trials is the selection of the dose, formulation and dose schedule of the intervention agent. This crossover study was designed to evaluate the bioavailabilty and tolerability of two preparations of beverages prepared from 3-day-old broccoli sprouts in order to administer the chemopreventive agent sulforaphane: [i] enterically generated from its cognate glucosinolate (glucoraphanin) by thioglucosidases found in the gut microflora (GRR), and [ii] pre-released when the GRR beverage was treated with myrosinase from the daikon plant Raphanus sativus to catalyze hydrolysis of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane (SFR). Substantial differences were observed between the two formulations in terms of bioavailability and palatability, both of which influence the utility of broccoli sprouts beverages as useful agents for chemoprevention studies in humans.

Doses of sulforaphane (150 μmol) and glucoraphanin (800 μmol) within each beverage were selected on the basis of literature reports of earlier studies and were intended to provide bioequivalence in SFT elimination together with reasonable tolerability. First, we had previously used a single dose of 200 μmol sulforaphane in a broccoli sprout preparation in women undergoing reduction mammoplasty to determine uptake of the isothiocyanate into breast tissue (30). Second, very small in-patient studies in healthy volunteers had defined uptake and elimination kinetics with a single dose of approximately 150 μmol sulforaphane (23) or three 25-μmol doses administered daily for 7 days (31). In no instances were any adverse effects reported. Additionally, from these studies it was estimated that ~70% of the administered sulforaphane was excreted as derivatives of glutathione conjugates in urine over the subsequent 24 hour interval. Third, our 2003 intervention trial in Qidong utilized a glucosinolate-rich formulation of broccoli sprouts containing 400 μmol glucoraphanin. Estimates of total sulforaphane excretion in these individuals indicated 18% of the administered glucosinolate was excreted as isothiocyanate derivatives over the subsequent 24 hours, with a range of 2–50% amongst the 100 study participants (20). No adverse events or issues with compliance were noted in this study as well. Shapiro et al (31) also noted an 18% recovery of SFT following dosing with 100 μmol GRR. Based upon these outcomes, a dose of 800 μmol glucoraphanin in the GRR beverage was chosen in anticipation of providing equivalent elimination totals (~100 μmol) of sulforaphane and metabolites between the two formulations. This prediction was not met.

The bioavailability of sulforaphane administered as SFR was far superior to GRR. Despite the attempt to match overall excretion yields between the two formulations, participants receiving the SFR had a 3-fold greater excretion of SFT than did those receiving GRR. As seen from Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 1, in both formulations excretion of SFT was essentially complete within 24 hours of dosing. Estimates of the AUCs derived from the excretion patterns depicted in Figure 4 suggest that 70% of the administered sulforaphane in the SFR beverage was eliminated in 24 hours; a finding very much in accord with earlier results (15, 23, 32). However, in the current study, only 5% of the administered glucoraphanin in GRR beverage was recovered as sulforaphane metabolites (SFT). Thus, despite doubling the dose of glucoraphanin compared to the 2003 intervention, somewhat less sulforaphane was hydrolyzed, absorbed, metabolized and eliminated in the current study. The reasons underlying the diminished bioavailability of GRR in the current study are not clear. A technical explanation could arise from the use of different analytical methods to measure SFT in the two studies: a colorimetric cyclocondensation assay (23) in 2003 and isotope dilution mass spectrometry (26) in 2009. However, a follow-up comparison of the two methods indicated they provided comparable measures of SFT in urine samples from the 2003 study (26). A biological basis for the differences could lie in different rates of hydrolysis of glucoraphanin to sulforaphane in the gastrointestinal tract between the two study populations. Intestinal microflora contribute substantially to this hydrolysis (15). At this time it is not clear which species of microflora harbor the thioglucosidases that catalyze this conversion, nor is it known to what extent this catalytic capacity varies under the influence of health status, age or dietary changes in humans. It is possible that other enzymes in the microflora or the host tissues divert sulforaphane to alternative, unmeasured products such as nitriles. That such factors are important can be inferred from the observation that the interindividual variability for excretion of SFT was significantly greater for participants receiving GRR compared to SFR beverage, irrespective of whether GRR was administered on the first or second wave (Table 2). Not all of the administered glucoraphanin was hydrolyzed in the gastrointestinal tract, as low amounts (typically 2–4 μmol) of glucoraphanin were excreted in urine daily in individuals receiving GRR. This is the first evidence of absorption and urinary elimination of intact glucoraphanin in humans, although Cwik et al. (33) have recently reported the excretion of unmetabolized glucoraphanin following its oral administration to dogs and rats.

Nonetheless, there was substantial interindividual variability in the AUCs measured for the participants also drinking the SFR beverage. It has been hypothesized that polymorphisms in GSTs, which participate in the conjugation of sulforaphane to ultimately yield the major excretion product, the mercapturic acid, could contribute to this variability (see Fig. 2) (25, 34, 35). Null genotypes of GSTs could be related to decreased metabolism and urinary excretion of isothiocyanates such as sulforaphane, thereby increasing the body burden of sulforaphane following dosing and leading to a more pronounced or protracted pharmacodynamic action. Such a notion was triggered by results from a case-control study in a Chinese population demonstrating that reduction in risk of lung cancer was associated with increased consumption of cruciferous vegetables, primarily among individuals null for GSTM1 and GSTT1 (36). By contrast, in a small broccoli feeding study (n=16) Gasper et al. (25) reported that individuals null for GSTM1 excreted sulforaphane at a faster rate and to a greater extent than did GSTM1-positive individuals. In a larger study (n = 100), Steck et al. (34) also observed that a greater proportion of individuals with the null GSTM1 genotype, but not the GSTT1 genotype, had higher urinary excretion rates of isothiocyanates following feeding of frozen/microwaved broccoli (myrosinase-inactivated) than did those with GSTM1 alleles present. They also observed substantial interindividual variability in the amount of SFT excreted in the 24 h following broccoli ingestion. Seow et al. (37) found an association between genotypes and urinary isothiocyate levels only among the consumers of the highest tertiles of cruciferous vegetable intake. In the current study we observed no effect of GST genotype, for either GSTM1 or GSTT1, on the AUCs (either for the initial 24 h or for the cumulative excretion with 7 days of dosing) for urinary elimination of total sulforaphane metabolites, regardless of whether they received GRR or SFR beverage. Similarly, in the 2003 Qidong intervention with a glucosinolate-rich beverage, no interaction between GST genotype and sulforaphane excretion was observed. Levels of sulforaphane intake in the two Qidong clinical trials, as adjudged by urinary SFT excretion levels, were substantially higher than those reported in the case-control or broccoli feeding studies. Collectively, the feeding studies with various formulations of broccoli indicate that GST genotypes are unlikely to have profound effects on sulforaphane disposition in humans. Whereas differential rates of hydrolysis of glucoraphanin may account for some of the variability in excretion rates with GRR, additional factors remain to be described that influence SFR elimination.

Although the wash-out phase of our cross-over study demonstrated clearly that virtually all sulforaphane metabolites were eliminated within 24 hours, irrespective of whether GRR or SFR was administered, there were substantive differences in the rates of elimination between the two formulations. With administration of SFR, 95% of the SFT was eliminated in the first 12 hours, compared to only 60% of the SFT when participants were dosed with GRR. Vermeulen et al. (38) have reported that in a small, randomized, free-living cross-over feeding trial of raw and cooked broccoli, higher amounts of SFT were found in the blood and urine when broccoli was eaten raw. In this instance the predominant component is sulforaphane whereas it is glucoraphanin in the cooked broccoli in which the myrosinase has been denatured. Peak plasma concentrations were achieved at 1.6 and 6 h, respectively, for raw and cooked broccoli. Clearly, excretion of SFT is delayed when broccoli or broccoli sprout preparations contain glucoraphanin instead of sulforaphane. Elimination half-lives of the sulforaphane mercapturic acid were comparable (~2.5 h), indicating again that the rate-limiting step for whole body elimination of glucoraphanin is likely the initial hydrolysis step. Interestingly, in this raw/cooked broccoli cross-over feeding study, the investigators also noted a better bioavailability when subjects were fed raw broccoli (SFT = 37% of the administered dose) compared to cooked broccoli (3.4%), a finding very much in accord with our results comparing SFR and GRR.

The different kinetics for uptake and elimination of SFT following administration of GRR versus SFR present a dilemma for the optimization of a broccoli-based food or beverage intervention. Sulforaphane exerts its cancer chemopreventive effects in experimental models through regulation of diverse molecular mechanisms, including activation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling, inhibition of NFκB, inhibition of histone deacetylases, induction of apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest (10, 39). Agents affecting multiple processes in carcinogenesis are likely to be more useful chemopreventive agents than those affecting a single target. However, the mechanisms of pathway activation and inhibition require different pharmacokinetic optimizations; pulsed, high peak concentrations for pathway activation and sustained concentrations for pathway or enzyme inhibition. SFR produces the former, whilst GRR favors the latter. Moreover, not all molecular actions of sulforaphane are triggered at the same concentrations. For example, activation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling occurs at substantially lower concentrations than does induction of apoptosis (2, 40). Thus, in the absence of clear understanding of the primary modes of action of sulforaphane and a consequent lack of understanding of how to optimize dose and duration within the target cells, we propose a blended approach may be most suitable for future interventions with broccoli sprout preparations, especially for large-scale, population-based interventions. Advantages of SFR include its better bioavailability and more rapid uptake, which are tempered by its more astringent taste. The taste in beverage formulation could be partially masked by admixing with mango juice, but more suitable masking materials are still required. SFR is intrinsically less stable than GRR, leading to additional logistical concerns about formulation, storage and distribution in settings of large, long interventions. By contrast, GFR, which is very stable and more tolerable to study participants, manifests variable but overall poor bioavailability. It does, however, provide a means to produce a more stable steady-state level of sulforaphane within the body. Future studies comparing the pharmacodynamic effects of these two formulations, individually, and perhaps combined, will be required to fully optimize food-based formulations containing sulforaphane, in addition to further evaluations of the impacts of dose and schedule on mechanistic or disease-based biomarkers.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig. 1. Selected ion mass chromatogram for glucoraphanin and [glucose-13C6]glucoraphanin internal standard in a urine sample collected from an individual receiving GRR beverage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Xin-Sen Zhang, Wei Chen and He-Chong Zhou of the He Zuo Public Health Station, the village doctors Yong-Ping Zhu, Han-Chang Yao and Jin-Yu Shi, for their assistance with the study and the residents of He Zuo for their participation. We also thank Kristina Wade, Jamie Johnson and Kevin Kensler (JHU) and the laboratory and clinical staff of the Qidong Liver Cancer Institute for logistical support throughout, especially Qi Nan Zhang, Mei Hua Yao, Long Zhang, and Yan Shen. Lastly, we thank Yong-Fei Xu for steadfast driving on the backroads of He Zuo during the nightly visits to the “tea” houses. Supported by USPHS grants P01 ES006052, R01 CA93780 and Center grant ES003819 and the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

Abbreviations used

- GRR

glucoraphainin-rich

- SFR

sulforaphane-rich

- SF

sulforaphane

- SF-GSH

sulforaphane-glutathione

- SF-CysGly

sulforaphane-cysteinylglycine

- SF-Cys

sulforaphane-cysteine

- SF-NAC

sulforaphane-N-acetylcysteine

- SFT

sulforaphane plus conjugates

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- AUC

area under the curve

- IQR

interquartile range

- CV

coefficients of variation

References

- 1.Kelloff GJ, Lieberman R, Steele VE, Boone CW, Lubet RA, Kopelovich L, Malone WA, Crowell JA, Higley HR, Sigman CC. Agents, biomarkers, and cohorts for chemopreventive agent development in prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57:46–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Talalay P, Cho CG, Posner GH. A major inducer of anticarcinogenic protective enzymes from broccoli: isolation and elucidation of structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2399–2403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nioi P, McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hayes JD. Identification of a novel Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response element (ARE) in the mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene: reassessment of the ARE consensus sequence. Biochem J. 2003;374:337–348. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinkova-Kostova AT. Chemoprotection against cancer: an idea whose time has come. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13:S122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Kensler TW, Cho CG, Posner GH, Talalay P. Anticarcinogenic activities of sulforaphane and structurally related synthetic norbornyl isothiocyanates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3147–3150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fahey JW, Haristoy X, Dolan PM, Kensler TW, Scholtus I, Stephenson KK, Talalay P, Lozniewski A. Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7610–7615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112203099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu C, Huang MT, Shen G, Yuan X, Lin W, Khor TO, Conney AH, Kong AN. Inhibition of 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced skin tumorigenesis in C57BL/6 mice by sulforaphane is mediated by nuclear factor E2-related factor 2. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8293–8296. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juge N, Mithen RF, Traka M. Molecular basis for chemoprevention by sulforaphane: a comprehensive review. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1105–1127. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higdon JV, Delage B, Williams DE, Dashwood RH. Cruciferous vegetables and human cancer risk: epidemiologic evidence and mechanistic basis. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riboli E, Norat T. Epidemiologic evidence of the protective effects of fruit and vegetables on cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:559–695. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.559S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington (District of Columbia): American Institute for Cancer Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.IARC. Cruciferous vegetables, isothiocyanates and indoles. Vol. 9. Lyon (France): IARC Press; 2004. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry. 2001;56:5–51. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P. Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1091–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahey JW, Zhang Y, Talalay P. Broccoli sprouts: an exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10367–10372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kensler TW, Qian GS, Chen JG, Groopman JD. Translational strategies for cancer prevention in liver. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:321–329. doi: 10.1038/nrc1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JS, Shen X, He X, Zhu YR, Zhang BC, Wang JB, Qian GS, Kuang SY, Zarba A, Egner PA, Jacobson LP, Munoz A, Helzlsouer KJ, Groopman JD, Kensler TW. Protective alterations in phase 1 and 2 metabolism of aflatoxin B1 by oltipraz in residents of Qidong, People's Republic of China. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:347–354. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egner PA, Wang JB, Zhu YR, Zhang BC, Wu Y, Zhang QN, Qian GS, Kuang SY, Gange SJ, Jacobson LP, Helzlsouer KJ, Bailey GS, Groopman JD, Kensler TW. Chlorophyllin intervention reduces aflatoxin-DNA adducts in individuals at high risk for liver cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14601–14606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251536898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kensler TW, Chen JG, Egner PA, Fahey JW, Jacobson LP, Stephenson KK, Ye L, Coady JL, Wang JB, Wu Y, Sun Y, Zhang QN, Zhang BC, Zhu YR, Qian GS, Carmella SG, Hecht SS, Benning L, Gange SJ, Groopman JD, Talalay P. Effects of glucosinolate-rich broccoli sprouts on urinary levels of aflatoxin-DNA adducts and phenanthrene tetraols in a randomized clinical trial in He Zuo township, Qidong, People's Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2605–2613. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson LP, Zhang BC, Zhu YR, Wang JB, Wu Y, Zhang QN, Yu LY, Qian GS, Kuang SY, Li YF, Fang X, Zarba A, Chen B, Enger C, Davidson NE, Gorman MB, Gordon GB, Prochaska HJ, Egner PA, Groopman JD, Munoz A, Helzlsouer KJ, Kensler TW. Oltipraz chemoprevention trial in Qidong, People's Republic of China: study design and clinical outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wade KL, Garrard IJ, Fahey JW. Improved hydrophilic interaction chromatography method for the identification and quantification of glucosinolates. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1154:469–472. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Wade KL, Zhang Y, Shapiro TA, Talalay P. Quantitative determination of dithiocarbamates in human plasma, serum, erythrocytes and urine: pharmacokinetics of broccoli sprout isothiocyanates in humans. Clin Chim Acta. 2002;316:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang L, Zhang Y, Jobson HE, Li J, Stephenson KK, Wade KL, Fahey JW. Potent activation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and arrest in S and M phases of cancer cells by a broccoli sprout extract. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:935–944. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasper AV, Al-Janobi A, Smith JA, Bacon JR, Fortun P, Atherton C, Taylor MA, Hawkey CJ, Barrett DA, Mithen RF. Glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism and metabolism of sulforaphane from standard and high-glucosinolate broccoli. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1283–1291. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Egner PA, Kensler TW, Chen JG, Gange SJ, Groopman JD, Friesen MD. Quantification of sulforaphane mercapturic acid pathway conjugates in human urine by high-performance liquid chromatography and isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1991–1996. doi: 10.1021/tx800210k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Q, Lebl T, Kulczynska A, Botting NP. The synthesis of novel hexa-13C-labelled glucosinolates from [13C6]-D-glucose. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4871–4876. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iori R, Bernardi R, Gueyrard D, Rollin P, Palmieri S. Formation of glucoraphanin by chemoselective oxidation of natural glucoerucin: A chemoenzymatic route to sulforaphane. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1047–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang B, Huang G, Wang D, Li A, Xu Z, Dong R, Zhang D, Zhou W. Null genotypes of GSTM1 and GSTT1 contribute to hepatocellular carcinoma risk: evidence from an updated meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 53:508–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornblatt BS, Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Erb M, Fahey JW, Singh NK, Chen MS, Stierer T, Garrett-Mayer E, Argani P, Davidson NE, Talalay P, Kensler TW, Visvanathan K. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of sulforaphane for chemoprevention in the breast. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1485–1490. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD, Stephenson KK, Wade KL, Ye L, Talalay P. Safety, tolerance, and metabolism of broccoli sprout glucosinolates and isothiocyanates: a clinical phase I study. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:53–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P. Chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of broccoli sprouts: metabolism and excretion in humans. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:501–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cwik MJ, Wu H, Muzzio M, McCormick DL, Kapetanovic I. Direct quantitation of glucoraphanin in dog and rat plasma by LC-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2010;52:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steck SE, Gammon MD, Hebert JR, Wall DE, Zeisel SH. GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1, and GSTA1 polymorphisms and urinary isothiocyanate metabolites following broccoli consumption in humans. J Nutr. 2007;137:904–909. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lampe JW. Interindividual differences in response to plant-based diets: implications for cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1553S–1557S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.London SJ, Yuan JM, Chung FL, Gao YT, Coetzee GA, Ross RK, Yu MC. Isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms, and lung-cancer risk: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Lancet. 2000;356:724–729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seow A, Shi CY, Chung FL, Jiao D, Hankin JH, Lee HP, Coetzee GA, Yu MC. Urinary total isothiocyanate (ITC) in a population-based sample of middle-aged and older Chinese in Singapore: relationship with dietary total ITC and glutathione S-transferase M1/T1/P1 genotypes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:775–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vermeulen M, Klopping-Ketelaars IW, van den Berg R, Vaes WH. Bioavailability and kinetics of sulforaphane in humans after consumption of cooked versus raw broccoli. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:10505–10509. doi: 10.1021/jf801989e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Tang L. Discovery and development of sulforaphane as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1143–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gamet-Payrastre L, Li P, Lumeau S, Cassar G, Dupont MA, Chevolleau S, Gasc N, Tulliez J, Terce F. Sulforaphane, a naturally occurring isothiocyanate, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HT29 human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1426–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig. 1. Selected ion mass chromatogram for glucoraphanin and [glucose-13C6]glucoraphanin internal standard in a urine sample collected from an individual receiving GRR beverage.