Abstract

Objective

To quantify how overweight children have to be for their mothers to classify them as overweight and to express concern about future overweight, and to investigate the adiposity cues in children that mothers respond to.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Subjects

531 children from the Gateshead Millennium Study cohort at 6-8 years and their mothers.

Measurements

In the mother: responses to two questions concerning the child's adiposity; height; weight; educational qualifications; economic status. In the child: height; weight; waist circumference; skinfold thicknesses; bioelectrical impedance; bone frame measurements.

Results

The body mass index (BMI) at which half the mothers classify their child as overweight was 21.3 (in the obese range for children of this age). The BMI at which half the mothers were concerned about their child becoming overweight in the future was 17.1 (below the overweight range). Waist circumference and skinfolds contributed most to mothers' responses. While BMI and fat scores were important predictors individually, they did not contribute independently once waist circumference and skinfolds (their most visible manifestations) were included in the regression equations. Mothers were less likely to classify girls as overweight. Mothers with higher BMIs were less likely to classify their child as overweight but were more likely to be concerned about future overweight.

Conclusion

Health promotion efforts directed at parents of young primary school children might better capitalise on their concern about future overweight in their child than on current weight status, and focus on mothers' response to more visible characteristics than the BMI.

Keywords: Epidemiologic studies, overweight, adiposity, child, perception

Introduction

Many studies report that parents fail to recognise overweight or obesity in their child.1-3 They have mostly studied mothers, and typically the outcome variable is whether the mother of an overweight child, according to a particular body mass index (BMI) criterion, recognises that her child is overweight. Most mothers do not. Two possible reasons are that they are insensitive to their child's fatness, or that they are using different criteria for overweight. This would not be surprising since the criteria vary even within the academic and clinical community. For example, in the studies reported in a meta-analysis1 five different criteria were used. There is no reason why mothers should know what these criteria are, or which one their child is being compared to. For mothers to use different criteria, though, is not the same as their being generally insensitive to a child's fatness. One new question that needs to be answered, then, is: at what point do mothers decide their child is overweight?

A further question concerns the body characteristics which lead a mother to classify a child as overweight. They are unlikely to be able to estimate the child's BMI intuitively, without measuring their height and weight. Even health professionals are poor at this, and they too tend to underestimate overweight (and obesity).4 Mothers may respond to more observable peripheral indicators that are correlated with the BMI such as waist circumference and skinfolds. Even bone frame size might influence mothers' judgements if they feel they have a ‘big’ child rather than a ‘fat’ one. Their responses might also vary with the child's sex and with their own BMI.3

Mothers' concern about their child becoming overweight in the future is also of interest because those who are not concerned might not be motivated to alter their child's diet or activity patterns. It might be expected that mothers will not be concerned about future overweight in their child, even if they think their child is overweight at the moment, as qualitative work suggests they may regard adipose tissue in early childhood as transitory ‘puppy fat’.5, 6

Using a range of child body measurements as predictor variables and the responses from two questions from mothers as outcome variables, we addressed two aims in a large population-based study. The first aim was to quantify the point at which mothers classify their child as overweight. The second aim was to quantify the point at which mothers express concern about their child becoming overweight in the future. In relation to both these outcome variables we examined (a) which anthropometric measures were most strongly predictive of the mother's responses, and (b) whether the mother's responses were related to child sex and maternal BMI.

Methods

Sample

A sample of 1029 infants born to 1011 mothers was recruited shortly after birth in 1999/2000 to the longitudinal Gateshead Millennium Study (GMS). Full details of the study are reported elsewhere.7, 8 All children whose families had not previously asked to leave the study were eligible to participate in the 6-8 years data sweep (n=928).

Procedure

Specially trained researchers visited mothers at home and their children at school. Mothers gave written consent, completed a series of questionnaires, and their height and weight were measured. Children gave written assent and body measurements were taken. A favourable ethical opinion was obtained from Gateshead Local Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

The two outcome variables used were responses to two questionnaire items taken from a previous study:9 ‘How would you describe your child's weight at the moment?’ (very underweight, underweight, normal, overweight or very overweight); and ‘How concerned are you about your child becoming overweight in the future?’ (unconcerned, a little concerned, concerned, fairly concerned, very concerned).

Predictor variables included the children's body measurements as follows:

Height measured twice to 0.1 cm with the head in the Frankfort plane using a Leicester portable height measure, and weight measured twice to 0.1 kg using Tanita scales TBF-300MA. Mothers' height and weight were measured in the same way. These measures were used to calculate the BMI.

Waist circumference measured twice to 0.1 cm using a tape measure to obtain the minimum circumference between the suprailiac crest and lower ribs at the end of normal expiration without compressing the skin. Skinfold thickness measured twice to 0.1 mm on the child's non-dominant side using a Holtain skinfold calliper in the following positions: biceps, midline of the anterior aspect of the arm; triceps, midline of the posterior aspect of the arm; subscapular, inferior to the inferior angle of the scapula; suprailiac, position 1 cm above and 2 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine.10-12 These provide additional fatness measures that are more directly observable than the BMI.

Bioelectrical impedance measured leg-to-leg using Tanita scales TBF-300MA. This provides a measure related to lean tissue mass from which fat mass was calculated. This is a more specific measure of fatness than the BMI.

Bone frame measured once to 0.1 cm across two points in the: shoulder (biacromial) and hips (biiliac) using a Harpenden Anthropometer, and knee (bicondylar femur), wrist (across the styloid process) and elbow (across the humeral epicondyles) using a Harpenden Bicondylar Calliper.13, 14 This provides a measure of skeletal size.

Maternal educational qualifications and a binary measure of economic status were collected at recruitment shortly after birth (details in Table 1). These variables are potential confounders which could be related both to the mother's decisions and to the child's fatness. Families were also classified by the Townsend deprivation index based on 1991 census data for each postcode. This divides households in the Northern Region into five ordered centiles, each comprising 20% of the population.15 This variable was used to examine the representativeness of the sample but was not otherwise used in the data analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline socio-economic characteristics of families in the original cohort and the sample used in this paper. Overall n=1011 for the original cohort and 531 for this sample; the numbers below are lower due to missing responses for some variables.

| Original cohort | This sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| n | % | n | % | |

|

|

|

|||

| Townsend quintile | ||||

| 1(most affluent) | 156 | 16 | 99 | 19 |

| 2 | 204 | 20 | 116 | 22 |

| 3 | 227 | 23 | 118 | 22 |

| 4 | 226 | 22 | 98 | 19 |

| 5 (least affluent) | 192 | 19 | 94 | 18 |

|

|

|

|||

| 1005 | 100 | 525 | 100 | |

| Mother's highest qualification | ||||

| Degree or equivalent | 166 | 18 | 109 | 22 |

| A levels or equivalent | 77 | 8 | 48 | 10 |

| GCSEs or equivalent | 495 | 53 | 268 | 53 |

| NVQs or none | 194 | 21 | 80 | 16 |

|

|

|

|||

| 932 | 100 | 505 | 100 | |

| Economic status | ||||

| Higher* | 495 | 49 | 310 | 58 |

| Lower | 514 | 51 | 221 | 42 |

|

|

|

|||

| 1009 | 100 | 531 | 100 | |

Family owns home and has car and at least one wage earner

Percentages do not always add up to 100 due to rounding

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 and SPSS version 17.0. UK growth reference centiles were calculated using lmsGrowth.16 In the analyses two binary outcome variables correspond to the two aims in the introduction. For the first aim, mothers' responses concerning their child's current weight status were dichotomised into a ‘not overweight’ category (very underweight, underweight or normal weight) versus an ‘overweight’ category (overweight or very overweight). For the second aim, mothers' responses to whether they were concerned about their child becoming overweight were dichotomised into the ‘unconcerned’ category versus a ‘concerned’ category (any of the other four responses).

The predictor variables are the same for both aims. The mean of all duplicate anthropometric measurements was used. BMI (wt/ht2) was calculated from height in m and weight in kg. Two other summary measures were calculated: a skinfold score (mean of the four skinfold thicknesses each expressed as a standardised score); and a bone frame score (mean of the five bone frame sizes each expressed as a standardised score). The bioelectric impedance data were used to calculate the fat free mass, and this was subtracted from total body mass to give the fat mass. This was then adjusted for age and height using multiple regression and the fat mass expressed as a standardised score (the fat score). Further details of this procedure are available.17

Categorical variables were described as proportions and continuous variables as medians and ranges since their distributions were generally skewed. Comparisons between families in the sample used in this paper and those lost to follow-up were made using χ2 tests. Spearman's ρ was used for correlations. Logistic regression was used to examine relationships between the two binary outcome variables and the predictor variables, with effect sizes expressed as odds ratios and statistical significance evaluated using likelihood ratios and the Wald statistic. Backward selection was used for model simplification. Because we were interested in comparing the BMI at which mothers decided their child was overweight and the BMI at which they started to become concerned about future overweight, any predictor variable that was significant at p<0.1 in analyses with either outcome variable was retained in the final regression models.

Results

Participants

Data were collected from 619 of the 928 children eligible for the 6-8 year data sweep. The analysis for this study was restricted to children for whom we had responses to both questions from the mother and the child's BMI (n=545). To ensure statistical independence one twin from each pair (n=14 at 6-8 years) was dropped at random, giving a final sample of 531.

Characteristics of the families in the original cohort and those in the sample used in this paper are shown in Table 1. The sample used in this paper has a higher proportion of the most affluent and better educated families, showing that they were less likely to be lost to follow-up. Statistical comparison of the families in this sample and the families lost to follow-up using χ2 tests showed significant differences at p<0.001 for each of the three variables in Table 1.

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the participants. The median BMI was 16.1 (range 12.3 to 27.0) in boys and 16.5 (range 12.5 to 26.2) in girls, corresponding to the 62nd and 65th centiles respectively of the UK 1990 growth reference.16, 18, 19 The proportion above the 91st centile, and therefore overweight by the current UK clinical criterion20 was 20%. Correlations between the children's anthropometric measures are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Characteristics of children and mothers at 6-8 years (n=531)

| n | % | Median | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Age (years) | 531 | 100% | 7.4 | 6.4 | 8.6 |

| Sex | |||||

| Boys | 270 | 51% | |||

| Girls | 261 | 49% | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 531 | 100% | 16.3 | 12.3 | 27.0 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 523 | 99% | 55.9 | 43.9 | 84.7 |

| Skinfold thickness (mm) | |||||

| Biceps | 513 | 97% | 6.3 | 2.7 | 30.1 |

| Triceps | 506 | 95% | 10.5 | 3.1 | 32.6 |

| Subscapular | 491 | 93% | 6.6 | 2.8 | 40.0 |

| Suprailiac | 481 | 91% | 7.9 | 2.7 | 38.8 |

| Summary skinfold score* | 517 | 97% | −0.3 | −1.1 | 4.8 |

| Fat score | 529 | 100% | 0.4 | −2.6 | 2.7 |

| Bone frame size (cm) | |||||

| Shoulder | 484 | 91% | 27.9 | 23.4 | 32.8 |

| Hip | 484 | 91% | 20.3 | 17.0 | 32.0 |

| Knee | 492 | 93% | 7.7 | 6.2 | 9.9 |

| Wrist | 492 | 93% | 4.3 | 3.6 | 5.3 |

| Elbow | 492 | 93% | 5.2 | 4.1 | 7.3 |

| Summary bone frame score* | 493 | 93% | −0.1 | −2.1 | 3.5 |

| Mother's BMI (kg/m2) | 490 | 92% | 25.0 | 16.8 | 64.3 |

Sum of individual variables expressed as standardised scores

Table 3.

Correlations (ρ) between child body measurements

| BMI | Waist circumference |

Skinfold score |

Fat score | Bone frame score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference | 0.91** | ||||

| Skinfold score | 0.87** | 0.81** | |||

| Fat score | 0.72** | 0.67** | 0.71** | ||

| Bone frame score | 0.74** | 0.76** | 0.61** | 0.40** | |

| Height | 0.42** | 0.55** | 0.36** | 0.14** | 0.79** |

p<0.01 (two tailed) N varies from 484 to 531

Mothers' perception that their child is overweight

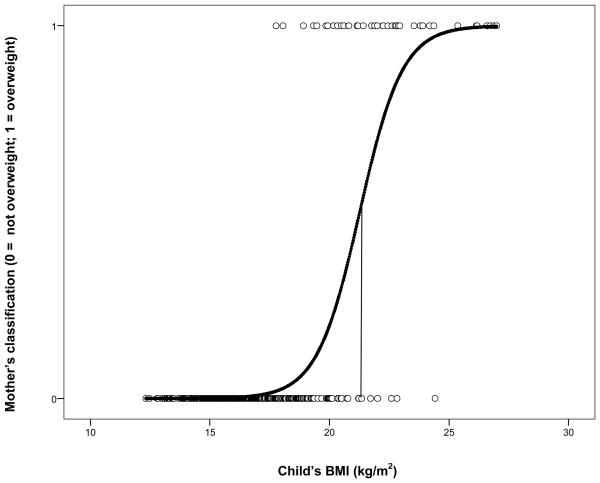

Mothers classified 492 children (93%) in the ‘not overweight’ category and 39 (7%) in the ‘overweight’ category. Figure 1 shows the mothers' classification plotted against the child's BMI. A logistic regression fits the curve also shown in Figure 1, ln(p/1-p) = −23.475 + 1.102 (BMI); the Wald statistic for BMI is 56.3 with 1df, p<0.001. A similar analysis showed that mothers' classification of their child as overweight was significantly related to the other fatness measures (waist circumference, skinfold score and fat score each at p<0.001). From the regression equations, the levels for each fatness measure at which 50%, 85% and 95% of mothers rated their child as overweight were calculated (Table 4). The BMI of 21.3 at which 50% of mothers classify their child as overweight corresponds to the 99th centile for both males and females on the UK 1990 growth reference.16

Figure 1.

Mothers' classification of their child's weight status plotted against their child's measured BMI. The curve is the probability of the mother classifying the child as overweight, as determined from the logistic regression of the binary response on BMI. A probability of 0.5 (50% of mothers) corresponds to a BMI of 21.3, as shown by the vertical line.

Table 4.

Levels of four different fatness variables at which 50%, 85% and 95% of mothers (a) classify their children as currently overweight and (b) express concern that their child will become overweight. The proportions are derived from logistic regression equations (see Results)

| (a) child is currently overweight |

(b) child will become overweight |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 85% | 95% | 50% | 85% | 95% | |

|

|

||||||

| BMI | 21.3 | 22.6 | 24.0 | 17.1 | 20.9 | 23.6 |

| Waist circumference | 67.8 | 71.7 | 74.5 | 57.8 | 67.5 | 74.3 |

| Skinfold score | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 2.2 |

| Fat score | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

For units see Table 2

When all four fatness measures were entered simultaneously, waist circumference and skinfold score contributed independently to the mothers' decisions (p<0.002 for each) but BMI and the fat score did not. When height and bone frame score were used as control variables neither was statistically significant. Nonetheless, the bone frame score was kept in as a control variable so that the regression models with the two different outcome variables were otherwise identical.

Using these body size variables (waist circumference, skinfold score and bone frame score) the effect of the child's age, sex and maternal BMI, and of the potential confounders (qualifications and economic status) was examined in five separate logistic regressions. Only sex and maternal BMI were significant at p<0.1 and these variables were retained in the multiple regression (Table 5a). This shows that for any level of the fatness measures in the child, mothers of girls were significantly less likely to classify their child as overweight, as were mothers with a higher BMI.

Table 5.

Results of multiple logistic regression analyses for the two outcome variables on body measurements, child's sex and maternal BMI (n=443)

| a) Mothers' classification of their child's weight status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|

|

|||||

| Child's waist circumference | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.33 | 1.07 to 1.65 |

| Child's skinfold score | 2.23 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 9.34 | 3.03 to 28.76 |

| Child's bone frame score | −0.86 | 0.61 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.13 to 1.41 |

| Child's sex (female) | −1.88 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.03 to 0.80 |

| Maternal BMI | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.88 | 0.79 to 0.97 |

| b) Mothers' concern about their child becoming overweight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|

|

|||||

| Child's waist circumference | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 1.08 to 1.28 |

| Child's skinfold score | 0.77 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 1.28 to 3.64 |

| Child's bone frame score | −0.48 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.62 | 0.41 to 0.95 |

| Child's sex (female) | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 1.24 | 0.76 to 2.03 |

| Maternal BMI | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.10 |

For units see Table 2

Mothers' concern that their child will become overweight

Mothers were concerned about their child becoming overweight in 244 (46%) cases. Of the mothers who thought their child was currently overweight, all were concerned about overweight in the future. Of the mothers who did not, 41% were concerned. Relating this outcome variable to the child's BMI, the equation for the fitted curve was ln(p/1-p) = −7.651 + 0.448 (BMI); the Wald statistic for BMI was 67.6 with 1df, p<0.001. The mothers' concern about future overweight in their child was also significantly related to all three additional fatness measures. From the regression equations the levels for each fatness measure at which 50%, 85% and 95% of mothers expressed concern about their child becoming overweight were calculated (Table 4). The BMI of 17.1 at which 50% of mothers are concerned about their child's future weight corresponds to the 81st centile for males and the 75th for females on the UK 1990 growth reference.16

When all four fatness measures were entered simultaneously, again both waist circumference and skinfold score contributed independently to concern about future overweight (p<0.01) but the child's BMI and fat score did not. There was a significant effect of bone frame score but not of height.

Again, only child's sex and maternal BMI were statistically significant at p<0.1 so these were retained in the multiple regression. Table 5b shows that for any level of child fatness mothers with a higher BMI were significantly more likely to be concerned about future overweight, whereas a larger child bone frame size significantly reduced their concern.

Discussion

Key results

For half the mothers to see their child as overweight the child's BMI must be 21.3. This value can be compared with the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) BMI cut points for overweight in children of this age which are 18.2 for boys and 18.0 for girls.21 Fewer than half our mothers see their child as overweight even at the IOTF cut points for obesity (21.1 and 21.0 respectively). For 95% to do so the child's BMI must reach 24.0. The same message is found in a comparison with the usual UK clinical criterion for overweight (the 91st centile) which is 18.0 and 18.7 for boys and girls respectively, and for obesity (the 98th centile) which is 19.8 and 20.8 respectively.16

For half the mothers to be concerned about their child becoming overweight in the future the child's BMI must be 17.1, and it must be 23.6 before 95% are concerned. All the mothers who thought their child was currently overweight were concerned about overweight in the future.

Waist circumference and skinfolds contributed most to mothers' responses. While BMI and fat scores were important predictors individually, they did not contribute independently once waist circumference and skinfolds (their most visible manifestations) were included in the regression equations. Mothers were less likely to classify girls as overweight, and mothers with higher BMIs were less likely to classify their child as overweight but were more likely to be concerned about future overweight.

Strengths and limitations

This study of maternal perceptions of children's weight status was conducted on a large population based sample as recommended in a recent systematic review.1 It is common in community-based studies for attrition to be higher among the most deprived families22, 23 and Table 1 shows that the families in our sample were on average more affluent and less well educated than the families in the original cohort. This retention bias needs to be taken into account in considering generalisations from our results. However, the most affluent families were under-represented in the original cohort with only 16% coming from the most affluent quintile rather than the 20% in the Northern Region as a whole. The proportion in our sample (19%) is closer to this.

It is possible that mothers with overweight children were less likely to participate in the 6-8 year data sweep. We cannot examine this directly, but although this paper deals with adiposity, the focus of the study of the GMS overall has always been on growth rather than fatness.

All the anthropometric variables were measured by trained researchers using well-established methods. There is, of course, the general problem that none of these variables provides a direct measure of fatness. This is not, however, a serious limitation in this study, since our interest was in the characteristics that mothers respond to rather than in the measurement of fatness per se.

The outcome variables depended on the mothers' responses to single questions. While in principle this might restrict reliability, the questions are based on previously published work and are simple, and there is no obvious way of adding further questions that would assess the same thing.

To our knowledge this is the first study to quantify mothers' thresholds for attributing overweight to their children, and to quantify the extent to which these differ from standard BMI-based thresholds. The analyses we report are independent of the standard used, so the mothers' thresholds can be examined in relation to any standard, making the results more useful. We also established the threshold for concern for future overweight. In addition to BMI, the study used a range of other indicators of fatness, allowing us to show that mothers' responses are specifically related to more visible characteristics of her child than the BMI.

Interpretation

Although ‘overweight’ must normally be understood to mean too fat rather than too heavy, the BMI is not a direct measure of fatness: it provides a screening test rather than a diagnostic test24 and has the usual problems of false positives and false negatives. With this reservation, the present study replicates the well-documented finding that mothers are less likely to classify their children as overweight than either of the current BMI based standards used in the UK.18, 21 This does not, however, mean that mothers are insensitive to their child's weight status, and the analyses (e.g. Figure 1) clearly show that their judgements do vary systematically with the child's BMI.

BMI is correlated quite strongly with other fatness measures. Waist circumference and skinfolds each independently influenced the mothers' assessment of her child's weight status, whereas BMI itself and the fat score did not. Although these measures are highly correlated, the implication of this is not that the mother is failing to respond to the overall level of adiposity reflected in all the measures, including the BMI, but that there are additional and more specific responses to waist circumference and skinfolds, probably because they are more visible.

In this study, unlike earlier ones,9, 25 mothers with higher BMIs themselves were less likely to classify their child as overweight, perhaps because they are more used to bigger people. Girls were less likely to be reported as overweight. As girls do on average store more fat than boys,26 mothers' responses are consistent with this. Neither of the mothers' decisions was affected by either of the socio-economic variables, so these cannot have acted as confounders.

Does it matters whether a mother correctly classifies her child as overweight? It would if it led to appropriate behavioural changes, but the evidence from one study suggests that recognising overweight per se may not.27 In that study, parents who did classify their child as overweight correctly were no more likely to encourage healthy food choices or to encourage more physical activity than those who did not. They were more likely to encourage dieting, but this was associated with greater subsequent weight gain.

Although being obese can have adverse health effects in childhood,28 much of the concern is that overweight may ‘track’ into adulthood.29 Mothers seem to share this concern. They expressed concern that their child might become overweight in the future at a much lower BMI than for current overweight (50% at 17.1 rather than 21.3). Similar results were found for the other fatness measures. There was no indication that mothers thought excess weight (‘puppy fat’) would be lost as children grew up - indeed all the mothers who considered their child overweight were also concerned that they would be overweight in the future. There is evidence from other studies that mothers' use of strategies to avoid excess weight gain are specifically related to concern about their child becoming overweight, rather than concern about their current weight.30, 31

Mothers who were more overweight themselves were more likely to be concerned about their children becoming overweight, as in previous studies.9, 30, 32 This is appropriate as the risk is in fact greater if the mother is overweight herself,33-35 especially if the child is a girl.36

Implications

Health promotion programmes aimed at parents of young primary school children may do better to concentrate on waist circumference and skinfold thickness than the BMI, since our results suggest that they are more salient to mothers. The finding that mothers express concern about future overweight at much lower levels of fatness than when asked about current overweight suggests that it may be better to capitalise on this rather than to deal directly with current overweight, particularly as there is evidence that mothers are more likely to take action to prevent their child gaining too much weight if they have concern about future overweight. The GMS is a birth cohort recruited within a calendar year so the sample has a narrow age range (6-8 years). It would also be useful to examine mothers' perception at other ages, for example in infancy and adolescence, using the same quantitative methods.

Acknowledgements

The Gateshead Millennium Study was supported by a grant from the National Prevention Research Initiative (incorporating funding from British Heart Foundation; Cancer Research UK; Department of Health; Diabetes UK; Economic and Social Research Council; Food Standards Agency; Medical Research Council; Research and Development Office for the Northern Ireland Health and Social Services; Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates; Welsh Assembly Government and World Cancer Research Fund). The cohort was first established with funding from the Henry Smith Charity and Sport Aiding Research in Kids (SPARKS) and followed up with grants from Gateshead NHS Trust R&D, Northern and Yorkshire NHS R&D, and Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Trust. We acknowledge the support of an External Reference Group in conducting the study. We appreciate the support of Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust, Gateshead Education Authority and local schools. We warmly thank the research team for their effort. Thanks are especially due to the Gateshead Millennium Study families and children for their participation in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Parry LL, Netuveli G, Parry J, Saxena S. A systematic review of parental perception of overweight status in children. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2008;31:253–268. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000324671.29272.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doolen J, Alpert PT, Miller SK. Parental disconnect between perceived and actual weight status of children: A metasynthesis of the current research. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Towns N, D'Auria J. Parental perceptions of their child's overweight: An integrative review of the literature. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith SM, Gately P, Rudolf M. Can we recognise obesity clinically? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:1065–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain A, Sherman SN, Chamberlin LA, Carter Y, Powers SW, Whitaker RC. Why don't low-income mothers worry about their preschoolers being overweight? Pediatrics. 2001;107:1138–1146. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones AR, Parkinson KN, Drewett RF, Hyland RM, Adamson AJ, the Gateshead Millennium Study core team Parental perceptions of body size and childhood adiposity at 6-8 years in the Gateshead Millennium Study. Obesity Facts. 2009;2:57. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkinson KN, Pearce MS, Dale A, Reilly JJ, Drewett RF, Wright CM, et al. Cohort Profile: The Gateshead Millennium Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq015. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkinson KN, Wright CM, Drewett RF. The Gateshead Millennium Baby Study: A prospective study of feeding and growth. Int J Soc Res Meth: Theory and Practice. 2007;10:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnell S, Edwards C, Croker H, Boniface D, Wardle J. Parental perceptions of overweight in 3-5 y olds. Int J Obes. 2005;29:353–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron N. The Measurement of Human Growth. Croom Helm Ltd; Kent: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison GG, Buskirk ER, Lindsay Carter JE, Johnston FE, Lohman TG, Pollock ML, et al. Skinfold thicknesses and measurement technique. In: Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Human Kinetics Books; Champaign, Illinois: 1988. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation . Physical status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Geneva: 1995. Report no: 854. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron N. The Methods of Auxological Anthropometry. In: Falkner F, Tanner JM, editors. Human Growth. Vol. 2. Bailliere Tindall; London: 1978. pp. 35–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilmore JH, Frisancho RA, Gordon CC, Himes JH, Martin AD, Martorell R, et al. Body breadth equipment and measurement techniques. In: Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R, editors. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Human Kinetics Books; Champaign, Illinois: 1988. pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. Health and Deprivation: Inequality in the North. Croom Helm; London: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan H, Cole T. User's Guide to lmsGrowth. Medical Research Council. 2002-09:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright CM, Sherriff A, Ward SCG, McColl JH, Reilly JJ, Ness AR. Development of bioelectrical impedance-derived indices of fat and fat-free mass for assessment of nutritional status in childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:210–217. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole T, Freeman J, Preece M. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73:25–29. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1998;17:407–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health . National Child Measurement Programme: Detailed Analysis of the 2006/7 National Dataset. London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. Br Med J. 2000;320:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dex S, Joshi H. Children of the 21st Century. Policy Press; Bristol: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rona RJ, Chinn S. The National Study of Health and Growth. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly JJ. Diagnostic accuracy of the BMI for age in paediatrics. Int J Obes. 2006;30:595–597. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffery AN, Voss LD, Metcalf BS, Alba S, Wilkin TJ. Parents' awareness of overweight in themselves and their children: cross sectional study within a cohort (EarlyBird 21) Br Med J. 2005;330:23–24. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38315.451539.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fomon SJ, Haschke F, Ziegler EE, Nelson SE. Body composition of reference children from birth to age 10 years. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;35:1169–1175. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, van den Berg P. Accurate parental classification of overweight adolescents' weight status: Does it matter? Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1495–1502. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly JJ, Methven E, McDowell ZC, Hacking B, Alexander D, Stewart L, et al. Health consequences of obesity. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:748–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.9.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JWR, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJM. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9:474–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford D, Timperio A, Telford A, Salmon J. Parental concerns about childhood obesity and the strategies employed to prevent unhealthy weight gain in children. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:889–895. doi: 10.1017/phn2005917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May AL, Donohue M, Scanlon KS, Sherry B, Dalenius K, Faulkner P, et al. Child-feeding strategies are associated with maternal concern about children becoming overweight, but not children's weight status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell MWC, Wiiliams J, Hampton A, Wake M. Maternal concern and perceptions of overweight in Australian preschool-aged children. Med J Aust. 2006;184:274–277. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lake J, Power C, Cole TJ. Child to adult body mass index in the 1958 British birth cohort: associations with parental obesity. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:376–381. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.5.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD. Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes. 1999;23:S1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Pastor EM, Metcalf BS, Hosking J, Jeffery AN, Voss LD, Wilkin TJ. Assortative weight gain in mother-daughter and father-son pairs: An emerging source of childhood obesity. Longitudinal study of trios (EarlyBird 43) Int J Obes. 2009;33:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]