Capecitabine is a novel oral fluoropyrimidine that is converted within tumor cells to fluorouracil by thymidine phosphorylase [1]. Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is the most frequent side effect of capecitabine and has been reported in up to 71% of patients receiving a starting dose of 1,250 mg/m2 twice daily [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Grade 3 HFS was reported in up to 10–24% of patients. Treatment interruption and, if required, dose reduction usually ameliorate symptoms without compromising efficacy [8, 9]. Supportive treatments such as topical wound care, elevation, and cold compresses may help to relieve pain [10, 11]. Use of systemic corticosteroids, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), and cox-2 inhibitors have been used in patients developing HFS with cytotoxic agents including capecitabine and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with varying success [11, 12, 13]. Kara et al. [13] from Turkey reported apparent benefit of vitamin E in managing HFS. Therefore we conducted this study to examine the efficacy of vitamin E in managing capecitabine-induced HFS.

This retrospective, multicenter study was undertaken between 2005 and 2009 in HER2-negative patients with breast cancer treated with oral capecitabine 828 mg/m2 twice daily on days 1–21 every 4 weeks. Patients with symptoms of grade 2 HFS received oral vitamin E (Tocopherol Acetate, Eisai Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan) 100 mg/day without chemotherapy dose modification. Patient and treatment-related data, e.g. chemotherapy-related toxicities, dose of vitamin E, severity of symptoms, and tumor response to therapy, were recorded every 4 weeks. Patients underwent a complete der-matological examination at every visit. HFS including pain was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 (NCI-CT-CAE v3.0). Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to examine patient demographics and treatment information. Median time to onset of grade 2 HFS was estimated. Severity of HFS was compared before and after vitamin E administration. We identified 32 patients developing grade 2 HFS during capecitabine therapy between January 2005 and February 2009, who subsequently received vitamin E with or without capecitabine treatment modification. The median time to first onset of HFS was 7.3 months (range 4.1–9.6). The initial starting dose of vitamin E for treatment of HFS was 100 mg/day, and the median dose of vitamin E was 200 mg (range 100–400 mg/day). Vitamin E application had a marked effect on dermatological complications within 7 days of initiation. The effect lasted throughout administration. Desquamation and pain reduced gradually (figs. 1] and 2), and the comfort level of the patients improved. Fifteen of 32 patients (46.9%) with HFS experienced symptom improvement with vitamin E (100 mg/day) (p < 0.05; before vs. after 2 months vitamin E administration). Neurological symptoms improved. Thirteen patients still had pain, but this decreased after vitamin E dose escalation to 400 mg/day. The remaining 4 patients had considerable pain interfering with function after vitamin E 100 mg/day, but this reduced after vitamin E dose escalation to 400 mg/day and dose reduction of capecitabine as described previously [14]. Among all 32 patients included, the overall response rate to capecitabine was 37.5%, comprising 2 complete and 10 partial responses. Patients receiving capecitabine and vitamin E (100–400 mg) had longer time to progression than did patients receiving dose reduction of capecitabine (median 10.2 months vs. 6.1 months).

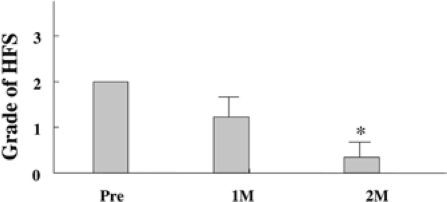

Fig. 1.

Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) began to disappear after 1 month of vitamin E treatment; 15 of 32 patients (47%) with HFS experienced symptom improvement with vitamin E (100 mg/day) (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Clinical presentation of hand-foot syndrome. After vitamin E without dose reduction of capecitabine, the skin lesions had disappeared.

In this retrospective study, 15 of 32 patients with HFS improved with vitamin E 100 mg/day, suggesting a beneficial effect of vitamin E therapy. Vitamin E is a widely used skin care product and functions as the major lipophilic antioxidant, preventing peroxidation of lipids and resulting in more stable cell membranes. The antioxidant membrane stabilizing effect of vitamin E also includes stabilization of the lysomal membrane, a function shared with glucocorticoids [13]. Systemic vitamin E and glucocorticoids inhibit the inflammatory response and collagen synthesis, thereby possibly impeding the

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to Mr. Nishikawa in Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, Sawada N, Ishikawa T, Mori K, Shimma N, Umeda I, Ishitsuka H. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1274–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fumoleau P, Largillier R, Clippe C. Multicentre, phase II study evaluating capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline-and taxanepretreated metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:536–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:485–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum JL, Dieras V, Lo Russo PM. Multicenter, phase II study of capecitabine in taxane-pretreated metastatic breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2001a;92:1759–68. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011001)92:7<1759::aid-cncr1691>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichardt P, von Minckwitz G, Thuss-Patience PC. Multicenter phase II study of oral capecitabine (Xeloda(")) in patients with metastatic breast cancer relapsing after treatment with a taxane-containing therapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1227–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA, Cobleigh MA, Marcom PK, Fehrenbacher L, Dickler M, Overmoyer BA, Reimann JD, Sing AP, Langmuir V, Rugo HS. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockler MR, Sourjina T, Grimison P. A randomized trial of capecitabine (C) given intermittently (IC) rather than continuously (CC) compared to classical CMF as first-line chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer (ABC) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1031. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blum JL, Jones SE, Buzdar AU, on behalf of the Xeloda Breast Cancer Study Group Capecitabine in 162 patients with paclitaxel-pretreated MBC: updated results and analysis of dose modification. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(suppl 6):190. (abstr 693). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard R, O'Shaughnessy J, Vukelja S. Detailed analysis of a randomized phase III trial: can the tolerability of capecitabine plus docetaxel be improved without compromising its survival advantage? Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1379–85. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frye DK. Capecitabine-based combination therapy for breast cancer: implications for nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:105–13. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gressett SM, Stanford BL, Hardwicke F. Management of hand-foot syndrome induced by capecitabine. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2006;12:131–41. doi: 10.1177/1078155206069242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassere Y, Hoff P. Management of hand-foot syndrome in patients treated with capecitabine (Xeloda) Eur J Oncol Nursing. 2004;8:S31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kara IO, Sahin B, Erkisi M. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia due to docetaxel-capecitabine therapy is treated with vitamin E without dose reduction. Breast. 2006;15:414–24. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto D, Iwase S, Kitamura K, Odagiri H, Yamamoto C, Nagumo Y. A phase II study of trastuzumab and capecitabine for patients with HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: Japan Breast Cancer Research Network (JBCRN) 00 Trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:509–14. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haller DG, Cassidy J, Clarke SJ. Potential regional differences for the tolerability profiles of fluoropyrimidines. J Clin Oncol. 2008;2:2118–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 188–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacouture ME, Wu S, Robert C. Evolving strategies for the management of hand-foot skin reaction associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Oncologist. 2008;13:1001–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asgari MM, Haggerty JG, McNiff JM. Expression and localization of thymidine phosphorylase/platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in skin and cutaneous tumors. J Cutaneous Pathol. 1999;26:287–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milano G, Etienne-Grimaldi M-C, Mari M. Candidate mechanisms of capecitabine-related hand-foot syndrome. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]