Abstract

Objectives. We compared the evolution of perception of discrimination from 1998 to 2007 among recent Arab (Muslim and non-Muslim) and Haitian immigrants to Montreal; we also studied the association between perception of discrimination and psychological distress in 1998 and 2007.

Methods. We conducted this cross-sectional comparative research with 2 samples: one recruited in 1998 (n = 784) and the other in 2007 (n = 432). The samples were randomly extracted from the registry of the Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities of Quebec. Psychological distress was measured with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25.

Results. The perception of discrimination increased from 1998 to 2007 among the Arab Muslim, Arab non-Muslim, and Haitian groups. Muslim Arabs experienced a significant increase in psychological distress associated with discrimination from 1998 to 2007.

Conclusions. These results confirm an increase in perception of discrimination and psychological distress among Arab Muslim recent immigrant communities after September 11, 2001, and highlight the importance this context may have for other immigrant groups.

Many studies have linked perceived discrimination based on racial, ethnic, or religious identity to poor mental and physical health.1 Discrimination is conceptualized as a range of stressors that include both explicit and implicit events experienced by individuals as well as structural prejudices.2 Major sociopolitical events can significantly alter stereotypes and discrimination,3 and numerous studies have reported increases in discrimination toward Arabs and Muslim minorities in the Western world since the events of September 11, 2001 (9/11).4–9 This is also the case in Canada, where increased security concerns were associated with negative stereotypes, racial profiling, and heightened scrutiny of Muslims and Arab immigrants.10–13 Beyond the magnitude of the events of 9/11, the discourse on security stemming from the war on terror generated suspicions and increased prejudice toward all groups considered a potential threat.14

It has been reported that negative portrayals based on externally attributed Arab or Muslim identities (in which people are identified by appearance, names, dress, and so forth) transform the ways in which individuals and groups shape their identities and provoke both a fragility of their sense of belonging to the host community15,16 and a reactive increase in group cohesion.17,18 In a comparative study of the Canadian social context and the American social context before 9/11, Ajrouch and Kusow19 documented how affiliation to Islam already represented a level of otherness that interacted with racial identity. After 9/11, some Canadian and American studies reported that the upsurge in discrimination was associated with transformations in the identities of Muslim minorities.20,21

Studies have attempted to link increased post-9/11 discrimination to psychological distress and mental and physical health consequences among US minorities.22,23 In Canada, qualitative studies have shown an upsurge in anxiety among Muslim minorities, associated with the targeting of their communities locally and globally.13,24,25 However, most of the research on the psychological consequences for Muslim minorities of the negative chain of events associated with the social and emotional turmoil after 9/11 has taken place in the United States.20 Furthermore, no existing studies have included pre-9/11 data or accounted for the socioeconomic conditions of immigrant groups, which may reflect structural discrimination.26 In addition, none of these studies have incorporated data from non-Arab or non-Muslim immigrant groups, who would be less likely to be directly targeted by discrimination related to 9/11 and subsequent related events.

Our objectives were (1) to compare perceived discrimination among recently arrived Arab (Muslim and non-Muslim) and Black Haitian immigrants to Montreal who were cross-sectionally sampled in 1998 and 2007 and (2) to assess the association, at each point in time, between self-reported discrimination and psychological distress, accounting for employment status and other important social factors such as premigratory exposure to violence. We hypothesized, consistent with other studies, that there would be a specific increase in perceived discrimination among Muslim Arab immigrants and that they would report greater psychological distress in 2007 than in 1998. Black Haitian immigrants were introduced as a comparison group. They historically experienced racial discrimination in Canada but were not specifically targeted by the media after 9/11.

METHODS

Montreal is a highly multiethnic city of approximately 2 million residents. It is the largest francophone city in North America, built on both a French heritage and a British influence, a combination that determines to a large extent the place of religion and the importance of language in public life. Intercommunity tensions between minorities and majority groups increased after 2001 and prompted the creation of a public commission that emphasized the need to discourage the stigmatization of Muslim and Arab communities and called for effective antiracism programs.27

Participants and Procedure

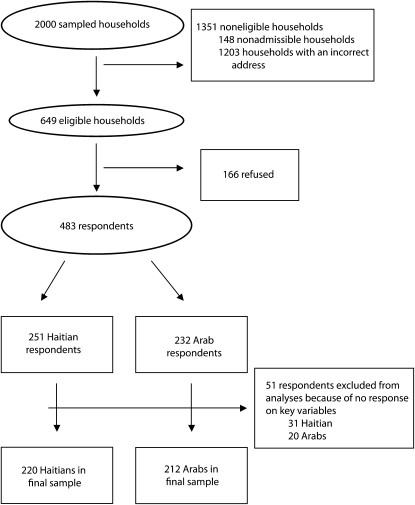

This study compared data from cross-sectional population samples of immigrants to Montreal who arrived before 9/11 (the 1998–1999 sample) and after 9/11 (the 2007 sample) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Selection of Arab and Haitian participants for study of perceived discrimination among newly arrived immigrants: Montreal, Quebec, 2007.

Sample 1 consisted of data from the Quebec Cultural Communities Survey (QCCS) collected in 1998 and 1999.28 The QCCS was a population-based health survey of recent immigrants who arrived in Canada between 1988 and 1997, were living in the metropolitan Montreal area, and were born in 1 of 2 geographical areas: North African and Middle Eastern Arab countries, and Haiti. Cluster sampling was used to select 1500 households stratified by ethnic group (750 Arabs and 750 Haitians) and by immigration period (1988–1992 and 1993–1997).

In 2007, we readministered the discrimination and mental health sections of the QCCS study with a sample comparable to that used in the original study (sample 2). A sample of 2000 households (1000 Arabs and 1000 Haitians), with at least 1 individual aged 18 to 65 years, was randomly extracted from the immigration registry of the Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities of Quebec.29 Participants had to meet 3 criteria: they (1) arrived in Canada between 1988 and 2006, (2) lived in the metropolitan Montreal area, and (3) were born or had their first citizenship in either a North African or Middle Eastern Arab country or in Haiti. The 2 samples (1998 and 2007) were cross-sectionally representative of the Montreal immigrant communities at these 2 time periods.

For sample 1 (1998), trained interviewers visited each sampled household (n = 1500) and informed the eligible participants about the purposes and procedure of the study.28 After informed consent was obtained, the key informant (aged 18 years or older) was invited to answer a self-administered questionnaire, along with all other individuals aged 15 years or older who were willing to participate in the study. If a household's participants could not be reached during the first visit, 6 attempted visits were made before recruitment efforts were discontinued. Interviews were conducted in French, English, or the respondent's language of choice.

For sample 2 (2007), eligible households received a letter during the summer and fall of 2007 describing the purposes and procedure of the study and informing them that they would be contacted shortly by telephone. Two weeks later, participants were contacted by a trained interviewer who asked to speak with the identified participant. If this participant was not available, the interviewer requested to speak to the eligible adult living in the household whose date of birth was closest to that of the identified participant. The interviewer administered the structured interview in the language of choice of the participant (Arabic, Creole, English, or French). Ten attempts to get in contact with the participant or household were made before it was decided that they could not be reached.

Instruments

Psychological instruments not available in Arabic and Creole were translated through the translation–back-translation procedure30 prior to the 1998 survey.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, length of stay in Canada, immigration status upon landing in Canada, level of education in home country, knowledge of French and English, present occupation, civil (e.g., marital) status, and personal income.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25.

Psychological distress was assessed with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (SCL-25), which consists of 25 items describing symptoms of anxiety (10 items) and depression (15 items).31 The total score for the SCL-25 is obtained by computing the mean of all items rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with scores of 1.75 and above indicating severe distress.32,33 The validity of the SCL-25 has been well established in transcultural settings with immigrant and refugee populations.9,34–37 The Cronbach α for 1998 was 0.95 for the Haitian sample (n = 379) and 0.94 for the North African and Middle Eastern sample (n = 405). In the 2007 study, the Cronbach α was 0.93 for the Haitian sample (n = 220) and 0.89 for the North African and Middle Eastern sample (n = 212).

Perception of discrimination.

In 1998, the 16-item multidimensional perceived discrimination scale developed by Noh et al.38 was administered. Respondents were first asked whether they had experienced discrimination because of their racial/ethnic or religious identity since their arrival in Montreal; their replies were used to establish the prevalence of perceived discrimination. In 2007, study participants who reported discrimination were also administered a separate test measuring the intensity and duration (short-term or long-lasting) of their emotional reactions to the experience of discrimination.39,40

Premigration exposure to political violence.

Two questions assessed whether study participants had witnessed acts of violence related to the social or political situation in their home country, and whether they or their family had experienced any of several forms of persecution there.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analyses were performed with the χ2 test and t test. A linear multiple regression model was generated that used psychological distress (SCL-25) as the dependent variable and religious group, discrimination in host country, persecution in country of origin, sociodemographic characteristics (gender and age), occupation, length of stay in Canada, year of data collection, and cultural origin of respondent as independent variables. An interaction term (religious group by year of data collection) was also introduced in the regression model. Collinearity statistics (tolerance and variance-inflation factor) were performed for covariates. The data were analyzed with SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Weight Data

To ensure representativeness, the 2 samples were weighted by the standard weighting procedure used by the Institut de la statistique Québec.28 We used sampling weights—that is, weights multiplied by a constant—so that the sum of all weights would equal the number of participants in the 1998 and 2007 studies. The results presented here were computed on the weighted samples.

RESULTS

Of the 1500 households in sample 1, a total of 628 were ineligible because respondents did not fulfill eligibility criteria for country of origin or immigration date (n = 121), because their address was missing (n = 54) or invalid (n = 453) or because they had moved to other cities or provinces. Of the remaining 872 households, a total of 214 refused to take part in the study and 76 could not be reached. Thus, 582 households took part in the study (314 Haitian and 268 Arab households), comprising 706 Haitian and 709 Arab individual respondents. Most interviews (n = 579) were conducted in French, with 35 interviews conducted in English, 127 in Arabic, and 43 in Creole. The sociodemographic profile of the 1998 nonparticipant sample is unknown.

Of the 2000 households in sample 2, a total of 1351 were ineligible because they did not fulfill the selection criteria (n = 148) or because their correspondence address was missing or incorrect (n = 1203). Thus, 649 households were eligible, of which 166 refused to participate. The final sample comprised 483 participants aged 18 years or older (1 participant per household); of the 483 participants, 251 were Haitian and 232 Arab. After data analysis, 51 respondents (31 Haitian and 20 Arab) were excluded because of missing key variables (such as discrimination and mental health). The final sample included in the analyses therefore comprised 432 individuals (220 Haitians and 212 Arabs). Participants who refused to take part in the 2007 study (n = 166) were asked to complete a short sociodemographic questionnaire to compare them with the participant population. The refusal rate was significantly higher for Arabs (59%) than for the total sample (49%) (P < .05), but there were no other significant or substantive differences between study participants and nonparticipants. A total of 395 interviews were conducted in French, 21 in English, 7 in Creole, and 9 in Arabic.

Characteristics of the Sample

Table 1 presents a comparison of the sociodemographic profiles of the 1998 and 2007 samples. Level of education and mastery of both official languages (French and English) were both significantly higher for the 2007 Haitian and Arab participants than for the 1998 participants, perhaps because there were higher levels of employment and salary in 2007. Compared with the 1998 sample, Arab participants in the 2007 survey had higher employment rates (P < .01), and both Haitian and Arab participants in the 2007 survey reported higher salaries.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Samples of Arab and Haitian Immigrants: Montreal, Quebec, 1998 and 2007

| Arab Immigrants |

Haitian Immigrants |

|||

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | 1998 | 2007 | 1998 | 2007 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 36.7 (14.5) | 37.2 (10.9) | 36.8 (15.0) | 36.84 (11.2) |

| Gender, no. (%) | ||||

| Men | 461 (52.1) | 196 (55.8) | 115 (40.5) | 38 (46.9) |

| Women | 423 (47.9) | 155 (44.2) | 169 (59.5) | 43 (53.1) |

| Length of stay in Canada, y, mean (SD) | 8.6 (5.0) | 9.2 (6.0) | 7.8 (3.1) | 10.8*** (5.2) |

| Immigration status upon landing in Canada, no. (%) | ||||

| Refugee | 91 (10.3) | 19** (5.6) | 38 (13.4) | 5 (6.7) |

| Other immigrant | 789 (89.7) | 322 (94.4) | 245 (86.6) | 70 (93.3) |

| Level of education in home country, no. (%) | ||||

| No schooling | 107 (13.9) | 24*** (7.1) | 42 (18.3) | 8*** (11.0) |

| Primary school | 152 (19.8) | 21 (6.2) | 89 (38.9) | 12 (16.4) |

| Secondary school | 98 (12.8) | 50 (14.8) | 30 (13.1) | 22 (30.1) |

| Postsecondary but no university | 125 (16.3) | 49 (14.5) | 38 (16.6) | 11 (15.1) |

| Some university | 286 (37.2) | 193 (57.3) | 30 (13.1) | 20 (27.4) |

| Knowledge of French,a mean score (SD) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.6*** (0.8) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.8*** (0.5) |

| Knowledge of English,a mean score (SD) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.9*** (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 2.5*** (0.9) |

| Present occupation, no. (%) | ||||

| Employed | 414 (46.9) | 170** (50.4) | 128 (45.2) | 41 (55.4) |

| Student | 228 (25.8) | 61 (18.1) | 80 (28.3) | 13 (17.6) |

| Homemaker | 174 (19.7) | 89 (26.4) | 44 (15.5) | 14 (18.9) |

| Others | 67 (7.6) | 17 (5.0) | 31 (11.0) | 6 (8.1) |

| Civil (marital) status, no. (%) | ||||

| Married | 504 (59.1) | 251*** (73.8) | 102 (38.3) | 38 (51.4) |

| Separated or divorced | 58 (6.8) | 10 (2.9) | 53 (19.9) | 9 (12.2) |

| Single | 270 (31.7) | 73 (21.5) | 101 (38.0) | 24 (32.4) |

| Other | 21 (2.5) | 6 (1.8) | 10 (3.8) | 3 (4.1) |

| Personal income, Can $, no. (%) | ||||

| None | 178 (25.2) | 60*** (17.9) | 37 (17.6) | 16*** (21.16) |

| ≤ 5999 | 148 (20.9) | 36 (10.7) | 39 (18.6) | 7 (9.5) |

| 6000–11 999 | 129 (18.2) | 53 (15.8) | 55 (26.2) | 9 (12.2) |

| 12 000–19 999 | 96 (13.6) | 35 (10.4) | 47 (22.4) | 11 (14.9) |

| 20 000–29 999 | 71 (10.0) | 51 (15.2) | 22 (10.5) | 17 (23.0) |

| ≥ 30 000 | 85 (12.0) | 100 (29.9) | 10 (4.8) | 14 (18.9) |

Scoring scale used for knowledge of language was from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very well).

*P < .05 ; **P < .01 ; ***P < .001.

Perception of Discrimination and Mental Health

Regardless of a respondent's cultural or religious group, perceived discrimination significantly increased from 1998–2007: from 31.0% to 54.3% for the Haitian participants and from 25.8% to 39.4% for the Arab participants (Table 2). There were no significant differences by gender in perception of discrimination.

TABLE 2.

Perception of Discrimination and Psychological Distress Among Haitians, Muslim Arabs, and Non-Muslim Arabs: Montreal, Quebec, 1998 and 2007

| 1998 |

2007 |

|||||||

| Haitians | Arabs | Muslim Arabs | Non-Muslim Arabs | Haitians | Arabs | Muslim Arabs | Non-Muslim Arabs | |

| Perceived discrimination, no. (%) | 79 (31.0) | 217 (25.8) | 100 (27.5) | 102 (23.5) | 44*** (54.3) | 138*** (39.4) | 86** (39.8) | 45** (37.5) |

| SCL-25,a mean (SD) | 1.34 (0.4) | 1.43 (0.4) | 1.45 (0.4) | 1.40 (0.4) | 1.37 (0.4) | 1.34*** (0.3) | 1.34** (0.3) | 1.33 (0.3) |

Note. SCL-25 = Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25. Numbers may not add to 100% because some respondents were missing data on religion.

The SCL-25 was used to measure psychological distress. The SCL-25 uses a 4-point Likert scale, with a score of 1.75 or above indicating severe distress.

*P < .05 ; **P < .01 ; ***P < .001.

For Haitian respondents, reported symptoms of psychological distress as measured by the SCL-25 were similar in 1998 and 2007 (P = .464); for Arab respondents, reported symptoms were significantly lower in the 2007 sample than in the 1998 sample (P < .001). However, discrimination was significantly associated with psychological distress for Muslim Arabs in 2007 (SCL-25 = 1.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.37, 1.68), whereas this was not the case either for their Arab non-Muslim counterparts in 2007 (SCL-25 = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.29, 1.45), or for both Muslim and non-Muslim Arabs in 1998.

Regression Model

The regression model (Table 3) explained 7.5% (standardized regression coefficients) of the variance in psychological distress, and no significant collinearity was found. According to the model, several variables—such as persecution experienced in country of origin, discrimination experienced in the host country, and being a female—significantly increased the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The Arab respondents presented, on average, more symptoms than did the Haitian respondents. Employment emerged as a protective factor against psychological distress. Interaction between 2 variables, religious group and year of data collection, was significant (B = 0.109; P = .013). Specifically, the impact of religious group (Muslim vs non-Muslim) was different for Arabs before and after 9/11. Before 9/11, being Arab and Muslim was a risk factor in terms of mental health (SCL-25 = 1.45 for Muslim Arabs and 1.40 for non-Muslim Arabs, P < .05), but this was no longer the case after 9/11 (SCL-25 = 1.34 for Muslim Arabs and 1.33 for non-Muslim Arabs, P > .05).

TABLE 3.

Regression Analysis of Psychological Distress Among Haitians, Muslim Arabs, and Non-Muslim Arabs: Montreal, Quebec, 1998 and 2007

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficient, b (SE) | Standardized Coefficient, B | P |

| Non-Muslim (ref = Muslim) | −0.090 (0.030) | −0.114 | .003 |

| Discrimination in host country (ref = no discrimination there) | −0.079 (0.024) | −0.094 | .001 |

| Persecution in country of origin (ref = no persecution there) | −0.106 (0.025) | −0.120 | < .001 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Women (ref = men) | 0.138 (0.023) | 0.177 | < .001 |

| Age | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.031 | .273 |

| Employed (ref = not employed) | −0.059 (0.023) | −0.076 | .01 |

| Length of stay in Canada | −0.002 (0.002) | −0.026 | .382 |

| Data collection in 2007 (ref = 1998) | −0.150 (0.034) | −0.179 | < .001 |

| Arab origin (ref = Haitian origin) | 0.067 (0.031) | 0.069 | .03 |

| Religious group × year of data collection | 0.121 (0.049) | 0.109 | .013 |

Note. Age and length of stay in Canada are continuous variables. Psychological distress was measured with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25.

Reaction to Discrimination in 2007

In the 2007 sample, 2 emotional reactions to discrimination were most frequently reported: (1) anger and (2) a feeling of becoming stronger and more confident. On average, approximately 4 of every 10 respondents declared having felt angry as a result of experiencing discrimination. This reaction was temporary; by contrast, the feeling of more strength and confidence, which was reported by approximately 70% of respondents who had been exposed to discrimination, was longer lasting (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Short-Term and Long-Term Reactions to Perceived Discrimination Among Haitians, Muslim Arabs, and Non-Muslim Arabs: Montreal, Quebec, 2007

| Haitians |

Arabs |

Muslim Arabs |

Non-Muslim Arabs | |||||

| Reaction to Discriminatory Situation | Short-Term, No. (%) | Long-Term, No. (%) | Short-Term, No. (%) | Long-Term, No. (%) | Short-Term, No. (%) | Long-Term, No. (%) | Short-Term, No. (%) | Long-Term, No. (%) |

| Felt scared or terrified | 21 (25.7) | 2 (2.6) | 55 (15.6) | 11 (3.0) | 45 (20.4) | 8 (3.6) | 8 (7.3) | 3 (2.4) |

| Felt weak or confused | 22 (26.8) | 2 (1.9) | 64 (18.3) | 8 (2.3) | 50 (22.6) | 4 (1.8) | 13 (11.3) | 4 (3.4) |

| Felt sad or depressed | 27 (33.8) | 3 (3.4) | 97 (27.6) | 13 (3.7) | 76 (34.1) | 9 (4.2) | 17 (15.2) | 4 (3.4) |

| Felt helpless, discouraged, or frustrated | 32 (39.5) | 4 (5.3) | 111 (31.7) | 18 (5.1) | 81 (36.4) | 14 (6.2) | 26 (23.3) | 4 (3.4) |

| Felt angry | 37 (45.0) | 4 (5.5) | 141 (40.3) | 22 (6.3) | 97 (43.7) | 17 (7.6) | 39 (34.4) | 5 (4.8) |

| Felt ashamed | 16 (19.3) | 2 (2.0) | 33 (9.5) | 3 (0.8) | 20 (8.8) | 1 (0.5) | 14 (12.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Felt strong or empowered | 54 (66.4) | 40 (49.2) | 239 (68.2) | 217 (62.0) | 153 (68.8) | 133 (60.0) | 82 (71.9) | 79 (70.0) |

Note. “Short-term” refers to participant's reaction at the time of the event. “Long-term” refers to the persistence of the reaction at the time of data collection.

DISCUSSION

The sharp increase in the perception of discrimination by both Haitian and Arab immigrants from 1998–2007 confirms the importance of 9/11 as a turning point in perceptions of prejudice. This increase is as important for Haitians as for Arabs, despite the fact that Arabs have been the objects of negative media attention much more often than have Haitians. This fact suggests that international tensions and the associated public discourse on national security have not only affected the more targeted groups (Muslims and Arabs) but may also have strained other local intercommunity relations (with more discrimination against all immigrant groups, along with a higher perception among immigrants of hostility or ambiguous treatment).14 The recent debates about the possible failure of the prevalent models of multiethnic society—in Canada as well as several European countries—may be seen as local reactions to the global sociopolitical situation and the debates in themselves may be partly responsible for this increase in a perception of discrimination.41 In Quebec, the public debate on minority–majority relations that took place during the period of data collection reflected a reemergence of local identity issues fueled by the global context of the war on terror, in which strangers become associated with potential threats.27 According to the Pew Institute,9 53% of Muslim Americans find that being Muslim in the United States is more difficult since 9/11, with 41% of native-born Muslims reporting having suffered discrimination there because of their religious affiliation compared with 25% of Muslim immigrants. Our results coincide with other Canadian qualitative studies in demonstrating that Muslim discomfort is also present in Canada,13,21,25 and that this global situation may have unexpected ripple effects on other majority–minority relations.

Given the increase in the perception of discrimination, the decrease in psychological distress among the 2007 Arab group is surprising. Underreporting of problems linked to the methodology of the survey is unlikely because underreporting would primarily affect the more sensitive questions (discrimination and premigratory persecution). Instead, the comparative analyses suggest that although Muslim Arabs report less psychological distress than do non-Muslim Arabs and Haitians, this relative advantage has decreased since 9/11. This may be linked to the fact that despite the rapid decline of violence and discrimination associated with “Islamophobia” in the months following 9/11, the levels of fear and “Islamophobia” have not concurrently declined.22

As expected, the regression model showed that perception of discrimination and premigratory persecution were risk factors for psychological distress, whereas employment played a protective role. Mental health scores were better in the 2007 sample than in the 1998 sample, which may be related to the improved economic situation in Quebec, with overall unemployment there dropping from 10.3% in 1998 to 7.2% in 2007. Indeed, the proportion of employed Arabs was significantly greater in 2007 than in 1998, although their employment rate still lagged significantly behind that of their Canadian counterparts with similar qualifications.26,42

Although these results document an increase in uneasiness among most resident Muslims similar to what was reported by the Pew Institute,9 the results contradict in part the alarmist positions stemming from studies that used retrospective methods to measure the impact of 9/11 on Muslim communities in Western countries. Methodologically, our results highlight the importance of pre–post data, even in cross-sectional samples, to assess the public health impact of major sociopolitical events, because the ideological and emotional nature of such events tend to elicit confirmatory bias within convenience samples when the impact of the events is documented retrospectively. The present results suggest that economic integration, which can be considered as a proxy for structural discrimination, may have a stronger global effect on minority psychological distress than on discrimination linked to discrete events and to prevalent social representations.

The general predominance, among both Haitians and Arabs, of reactive feelings of strength (and, to a lesser degree, anger) as the most important long-lasting effects of discrimination raises the hypothesis that discrimination targeting valued collective identities (e.g., Muslim) may reinforce group cohesion within minorities. This reactive cohesion, often reported in conflicts and war,43,44 has also been reported among Muslim youths in the United States since 9/11.45 The long-term consequences of this reactive cohesion on intercommunity relations in multiethnic societies could be quite significant, especially if the structural protection provided by a well-functioning economy begins to fail.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, because this was an observational study, it was not possible to draw causal conclusions based on the results alone. However, the findings are consistent with other evidence strongly suggesting that the post-9/11 context played a role in the shift in perception of discrimination. A longitudinal study that used the same participants before and after the events, and then compared them with a nonexposed sample, would have provided more robust evidence.

Second, the participation rates were not high, although the rates were relatively good given the sensitivity of the topic. The data collection differed for both points in time (1998 and 2007) in terms of the method of interview (face to face in 1998, by telephone in 2007) and number of participants from each household (more than 1 in 1998, only 1 in 2007). Such differences may have led to a sample bias. The nonresponse sociodemographic profile was not documented in the 1998 sample, although it was well described in the 2007 sample. However, in 2007, the subset of participants who did not answer questions related to perceived discrimination was excluded, and this exclusion may represent a bias. Furthermore, households were the basis of sampling for the 1998 sample, so the survey was answered by more than 1 person in a certain number of households, introducing a potential bias. Members of the same household can share similar characteristics and experiences and thus constitute nonindependent observations. The comparative designs of the 2 studies suggest differences in stratification according to year of arrival (1988–1998 for the 1998 sample and 1988–2006 for the 2007 sample). Even if the time in the host country is not significantly associated with the exposure and outcome variables, this difference constitutes a potential bias.

Finally, even if the samples can be considered representative of immigrant Arab and Haitian populations in metropolitan Montreal, the results regarding the association between psychological distress, the perception of discrimination, and social correlates may not be readily generalized to all large, multiethnic urban settings in North America because of the specificities of Quebec's social dynamics and environment.

Conclusions

Our research sheds light on the mental health aspects of intercommunity tensions stemming from 9/11, and also on the social turmoil in immigrant communities of large multiethnic urban settings following 9/11. Our findings suggest that the model associating psychopathology with prejudice is valid but may not be sufficient to explain the mental health consequences of discrimination linked to sociopolitical tensions. More research is needed to better understand the complex relationship between major events in a globalized world, discrimination, intercommunity relations, and individual mental health.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute for Health Research and with the collaboration of the Institut de la statistique du Québec.

Human Participant Protection

This research was approved by the research and ethics board of the Montreal Children's Hospital, Quebec, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- 1.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: conceptual and measurement problems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):262–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar-Tal D, Labin D. The effects of a major event on stereotyping: terrorist attacks in Israel and Israeli adolescents’ perceptions of Palestinians, Jordanians and Arabs. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2001;31(3):256–280 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balsano AB, Sirin SR. Commentary on the special issue of ADS Muslim youth in the West: “collateral damage” we cannot afford to disregard. Appl Dev Sci. 2007;11(3):178–183 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibish H, Carol K, Kareem S, Marvin W, Balajia K. 1998– 2000 Report on Hate Crimes and Discrimination Against Arab Americans. Washington, DC: American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibish H, Carol K, Kareem S, Marvin W, Stewart A. Report on Hate Crimes and Discrimination Against Arab Americans: The Post–September 11 Backlash. Washington, DC: American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmad I, Szpara MY. Muslim children in urban America: the New York City schools experience. J Muslim Minority Aff. 2003;23(2):295–301 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zine J. Unveiled sentiments: gendered Islamophobia and experiences of veiling among Muslim girls in a Canadian Islamic school. Equity Excell Educ. 2006;39(3):239–252 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muslim Americans: Middle Class and Mostly Mainstream. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Life for Canadian Muslims the Morning After: A 9/11 Wake-Up Call. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Council on American-Islamic Relations; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Presumption of Guilt: A National Survey on Security Visitations of Canadian Muslims. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Council on American-Islamic Relations; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merskin D. The construction of Arabs as enemies: post–September 11 discourse of George W. Bush. Mass Commun Soc. 2004;7(2):157–175 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helly D. Are Muslims discriminated against in Canada since September 2001? J Can Stud. 2004;36(1):24–47 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hörnqvist M. The birth of public order policy. Race Cl. 2004;46(1):30–52 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarroub LK. All American Yemeni Girls: Being Muslim in a Public School. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghazal Read J. Multiple identities among Arab Americans: a tale of two congregations. : Ewing KP, Being and Belonging: Muslims in the United States Since 9/11. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008:107–127 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewing KP, Hoyler M. Being Muslim and American: South Asian Muslim Youth and the War on Terror. : Ewing KP, Being and Belonging: Muslims in the United States Since 9/11. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008:80–104 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witteborn S. Of being an Arab woman before and after September 11: the enactment of communal identities in talk. Howard J Commun. 2004;15:83–98 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajrouch KJ, Kusow AM. Racial and religious contexts: situational identities among Lebanese and Somali Muslim immigrants. Ethn Racial Stud. 2007;30(1):72–94 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Britto PR, Amer MM. An exploration of cultural identity patterns and the family context among Arab Muslim young adults in America. Appl Dev Sci. 2007;11(3):137–150 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rousseau C, Jamil U. Meaning and perceived consequences of 9/11 for two Pakistani communities: from external intruders to the internalisation of a negative self-image. Anthropol Med. 2008;15(3):163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lauderdale DS. Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in California before and after September 11. Demography. 2006;43(1):185–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moradi B, Talal Hasan N. Arab American persons’ reported experiences of discrimination and mental health: the mediating role of personal control. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51(4):418–428 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rousseau C, Machouf A. A preventive pilot project addressing multiethnic tensions in the wake of the Iraq war. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(4):466–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razack S. Casting Out: The Eviction of Muslims From Western Law and Politics. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams M. Muslims in Canada: findings from the 2007 Environics Survey. Horizons. 2009;10(2):19–26 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchard G, Taylor C. Building the Future: A Time for Reconciliation. Final Report of the Commission de consultation sur les pratiques d'accomodement reliées aux différences culturelles. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institut de la statistique Québec Santé et bien-être, immigrants récents au Québec: Une adaptation réciproque? Étude auprès des communautés culturelles 1998–1999. Québec: Les Publications du Québec; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada 2006. Ottawa, Ontario: Canada Statistics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hesbacher PT, Rickels K, Morris RJ, Newman H, Rosenfeld H. Psychiatric illness in family practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980;41(1):6–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson EB, Rosser-Hogan R. Mental health status of Cambodian refugees ten years after leaving their homes. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mollica RF, Wyshak G, de Marneffe D, Khuon F, Lavelle J. Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: a screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(4):497–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mollica RF, Poole C, Son L, Murray CC, Tor S. Effects of war trauma on Cambodian refugee adolescents’ functional health and mental health status. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1098–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moum T. Mode of administration and interviewer effects in self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression. Soc Indic Res. 1998;45(1–3):279–318 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pernice R, Brook J. Refugees’ and immigrants’ mental health: association of demographic and post-immigration factors. J Soc Psychol. 1996;136(4):511–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreau N, Hassan G, Rousseau C. Perception that “everything requires a lot of effort”: a symptom or a normal expectation for immigrant subjects? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(9):695–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens E. Perceived racial discrimination, depression and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):193–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noh S, Kaspar V, Wickrama KAS. Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1269–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bigot D, Bonelli L, Deltombe T. Au nom du 11 septembre: les démocraties à l’épreuve de l'antiterrorisme. Paris, France: La découverte; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taux de chômage selon le groupe d’âge et selon le sexe, moyennes annuelles, Québec, 1976 à 2007. : Profil démographique de la population Québécoise. Québec: Institut de la statistique Québec; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bar-Tal D. Societal beliefs in times of intractable conflict: the Israeli case. Int J Conflict Manage. 1998;9(1):22–50 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punamäki R- L. Can ideological commitment protect children's psychosocial well-being in situations of political violence? Child Dev. 1996;67(1):55–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ewing KP. Introduction. : Ewing KP, Being and Belonging: Muslims in the United States Since 9/11. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008 [Google Scholar]