Many patients with chronic mood problems have given up—they’ve “learned” (concluded) they’re helpless.

The theory of learned helplessness was developed in 1967 when psychologists Seligman and Maier subjected dogs to a series of inescapable electric shocks. Later, when the dogs could escape by simply jumping over a low partition, many didn’t bother to try. These passive dogs were said to have learned that they were helpless.

Some patients endured “a series of inescapable shocks” in the past, but in their current lives face only “relatively low partitions” to improving emotional well-being. How do we explain that their helplessness might be more “learned” than real? How do we convince them to try again?

One tool I’ve found helpful is what I call the mood pie. It helps patients understand why they feel the way they do, and it increases self-compassion and responsibility—both powerful predictors of long-term emotional well-being.

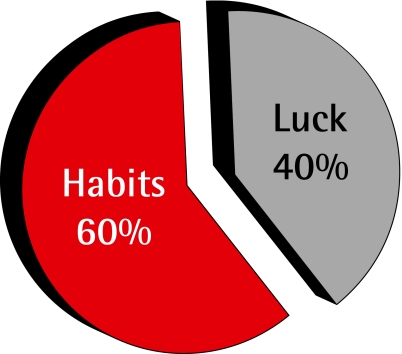

A basic mood pie requires only 2 pieces: habits and luck. Estimates are always approximate, but for all of us the long-term contribution of habits is extremely important. Here’s a happiness pie for a dysthymic patient:

Mood pies are useful for a range of emotions, including depression, anxiety, anger, loneliness, and grief. The goal is always to increase self-compassion and responsibility.

Slice one: luck

Luck refers to mood determinants beyond patients’ control. Review the luck part of the pie to increase self-compassion.

Genetics: If your 3 twins on Niihau also have dysthymic tendencies, then you’re genetically unlucky.

Date of birth: If you were born in 1929 instead of 1959, then, all things being equal, you were unlucky.

Place of birth: If you were born in Chernobyl instead of Côte-Saint-Luc, then you were unlucky.

Upbringing: If you grew up in a series of foster homes instead of a stable, loving family, then you were unlucky.

Adulthood: If your kids escaped illness, you were arguably lucky. If you trained in a job that was transferred off-shore, it’s likely you were unlucky.

Luckily, with tincture of time we can often see the good in our bad luck. As Hamlet said, “there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so”—although he also demonstrated that “reframing” isn’t easy. For the stoic John Milton, “To be blind is not miserable; not to be able to bear blindness, that is miserable.” But we’re not all Miltons.

A second slice: responsibility

Habits refer to factors within patients’ control. Review the habits part of the pie to increase responsibility.

Medication habits: Are you adequately adherent?

Exercise habits: Do you exercise with sufficient frequency, intensity, and duration?

Social habits: Are your social habits sufficient to maintain a solid sense of community?

Nutritional habits: Are they good in quality and quantity?

Financial habits: Do you live within your means?

Spiritual habits: Do they align with your values?

Mental habits: Do you have sufficient distraction and relaxation? Are you resistant to “cognitive distortions”?

Baker’s half-dozen

Vocalize your empathy. If you’d be upset to have your patient’s luck, go ahead and say so. If you too might be tempted to “go on strike” and invest only in petitioning the deities, go ahead and say so.

Dispute the “fallacy of fairness.” We must carry on in good faith, despite life’s often not seeming very fair.

Emphasize that the “why me?” question will never have a satisfying answer. As the ancient cognitive therapist Marcus Aurelius wrote, “Is your cucumber bitter? Throw it away. Are there briars in your path? Turn aside. That is enough.” Advise patients to throw away their bitter cucumbers and turn aside from their briars.

Encourage patients to use bad luck as an excuse for increased self-compassion. It’s enough that the deities or universe is picking on them.

Gratitude is a virtue that grows well only with conscious cultivation. Occasionally it might seem sensitive enough to emphasize that “it could be worse.”

Frame bad luck as a call to action. Bad luck is not a reason to play dead (nor to wish that one was). When our luck is bad, we can least afford to be sloppy in our allocation of our time and energy resources.

Counsel your patients to prepare for better luck. As Pasteur said, “Chance favours the prepared mind.”

Acknowledgments

I thank CBT Mexico 2010 participants Drs Charles Czarnowski, Shah Deen, Janina Dutkiewicz, Edward Karpinski, David Strydom, and Trish Turner for their helpful critique.

Footnotes

Next month: The CUE question