Abstract

This pilot clinical trial evaluated whether the efficacy of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) provided with limited psychosocial services is improved by the addition of manual-guided behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (BDRC). Heroin dependent individuals (N=37) enrolling in two MMT clinics in Wuhan, China, received standard MMT services, consisting of daily medication at the clinics and infrequent additional services on demand, and were randomly assigned to MMT only (n=17) or MMT with weekly individual BDRC (n=20) for 3 months. Participants were followed for six months from the time of enrollment (3 months active counseling phase and 3 months follow-up while treated with standard MMT). Primary outcome measures included reductions of HIV risk behaviors and illicit opiate use and treatment retention. Participants were 81% male; mean (SD) age 36.7 (7.2) years; there were no significant baseline differences between the two groups. Participants in MMT+BDRC achieved both greater reductions of HIV risk behaviors (p<0.01), as indicated by the scores on a short version of the AIDS Risk Inventory, and of illicit opiate use, as indicated by the proportions of opiate negative test results during the active phase of the study and the follow-up (p< 0.001). 83.3% in the MMT+BDRC group and 76.2% in the standard MMT group were still actively participating in MMT at 6 months. Manual-guided behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling is feasible to deliver by the trained MMT nursing personnel and appears to be a promising approach for improving the efficacy of standard MMT services in China.

Keywords: Methadone maintenance, drug counseling, HIV risk reduction counseling, China

1. Introduction

China has been experiencing a reoccurrence of illicit drug use problems since the late 1980s (Lu and Wang, 2008; Lu et al., 2008). The dominant drug of abuse is heroin, due to China’s proximity to two major areas of illicit heroin production: the Golden Triangle (an area overlapping the mountains of four countries of Southeast Asia: Myanmar/Burma, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand) and the Golden Crescent (an area outlined by the mountainous peripheries of Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan). At the end of 2009, there were 1.2 million registered drug users in China, with approximately 1 million of them primarily heroin abusers; however, China’s National Control Commission estimated that the actual number of drug users in China exceeds 3.5 million. Injection drug use (IDU) is very prevalent: about 50% of drug users report current IDU, and the majority of IDUs share injection equipment with others (Hammett et al., 2007: National Narcotic Control Commission, 2009; Wang, 2007). Currently, it is estimated that there are over 650,000 HIV infected individuals in China. Approximately half of these infections are attributable to risk behaviors associated with IDU, making injection drug users (IDUs) the largest single risk group for HIV infection in China (Wang et al., 2009). In addition to risky injecting practices, drug users in China also commonly engage in risky sexual practices. Most of China’s drug users are young, unmarried, and sexually active, and only a small fraction of them report consistent condom use. Their knowledge about HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and other blood borne viruses is very poor. The combination of poor knowledge and frequent engagement in high-risk behaviors increases their own risk of infection and also contributes significantly to the spread of HIV and STDs into the general population (Lau et al, 2008; Wang, 2007; Sullivan and Wu, 2007).

Recently, the Chinese government has taken several steps to curtail the spread of drug use and related problems and HIV, including rapid scale up of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) and harm reduction strategies, such as needle exchange programs. By the end of 2009, approximately 680 MMT clinics had been established with an estimated 150,000 heroin users receiving treatment (National Narcotic Control Commission, 2009). The programs have been well received, and over the next several years, China plans to develop more than 1,000 MMT clinics providing drug treatment to more than 300,000 heroin addicts. Despite showing considerable promise, there is still considerable room for improvement in the MMT programs in China: Retention averages <50% at six months and, despite reductions in drug use and HIV risks, many patients continue with these behaviors while still in MMT or reengage in them immediately after discontinuing treatment (Pang et al., 2007; Tang and Hao, 2007) .

One strategy for improving both short- and long-treatment outcomes associated with MMT is to provide effective drug and HIV risk reduction counseling along with MMT. Currently, however, methadone programs in China provide very little or no drug counseling (Pang et al., 2007; Tang and Hao, 2007), in part because of the difficulties of finding, hiring, training and supervising counselors and also because of the lack of data supporting the feasibility, efficacy or cost-effectiveness in China of providing drug counseling as part of MMT.

Consequently, this study set out to evaluate the feasibility and potential efficacy of providing a CBT-based drug counseling approach, Behavioral Drug and HIV Risk Reduction Counseling (BDRC), along with MMT in China. BDRC is premised on social learning theory and uses a small-step/small-success approach to behavioral changes aimed at engaging patients in rewarding activities and interactions that are unrelated to or incompatible with drug use. In prior studies in Malaysia, China, Thailand, and Iran, BDRC has been readily adapted to address the specific cultures, needs, and circumstances of participants, and available nursing or other personnel with limited or no prior experience in counseling or drug treatment have been trained to provide BDRC effectively (Chawarski et al, 2008).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Treatment seeking volunteers eligible for and entering methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) were enrolled after providing informed, voluntary consent at two MMT clinics in Wuhan, China. All individuals eligible for MMT were eligible to participate in the study. 86 individuals expressed interest in study participation; 54 completed the screening process; 9 were excluded because of their imminent plans to move in search of a new job; 45 individuals signed informed consent and were enrolled into the protocol. The first 8 study participants, 4 at each MMT clinic, 2 for each counselor, were training cases assigned to the MMT+BDRC condition in order to give the nurse counselors an opportunity to continue improving their mastery of the newly learned BDRC intervention. The remaining 37 participants were randomly assigned to either Standard MMT (n=17) or MMT+BDRC (n=20) using a simple randomization procedure (a computer generated randomization list in the US was used and randomization codes were provided to the research personnel in China on the day of randomization).

The study protocol was approved by the Human Investigation Committee (HIC) for the Yale University School of Medicine and the Wuhan Branch of China Preventive Medicine Association Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study was conducted in two outpatient MMT programs in Wuhan, China, between April 2008 and January 2010.

2.2. Methadone dosing

All study participants received methadone doses from their MMT programs, following the standard dosing protocols in the MMT programs in Wuhan. The average daily dose of methadone was 45 mg; the dose of methadone did not differ between the randomization groups, and all doses were dispensed at the clinics under the direct observation of the clinic staff.

2.3. Medical and psychosocial services

All study participants received an initial medical evaluation by a MMT physician not associated with the study to determine their MMT eligibility and overall health status provided. During MMT treatment, MMT patients were able to schedule brief visits with a physician, nurse, or a counselor on an “as needed” basis to address concerns or a crisis.

Participants assigned to MMT+BDRC also received weekly, manual-guided BDRC in individual sessions lasting 45-60 minutes. BDRC is suitable for provision by trained nursing personnel in medical offices, clinics and other health care settings. It provides education about heroin addiction and MMT and is directive and prescriptive about behavioral changes that facilitate abstinence and long-term recovery. BDRC counselors use short-term behavioral contracts aimed at improving treatment adherence and helping patients to make initial lifestyle changes, including cessation/reduction of drug use and cessation/reduction of drug- and sex-related risk behaviors. BDRC counselors also provides immediate feedback and positive reinforcement of patient progress, using exclusively a positively- or gain-framed communication style to increase the likelihood of patient adherence to treatment recommendations and engagement in behavioral change (Rothman and Salovey, 1993; Rothman et al., 1997). While initial stages of BDRC focus on behavioral changes necessary to achieve and maintain drug abstinence, later treatment stages help link the patient’s progress made in treatment with longer term recovery goals.

BDRC was provided by four nurse counselors, all with minimal prior drug counseling experience. All four nurses who initiated training completed training in BDRC (consisting of several didactic workshops, case conferences and treating two closely supervised BDRC practice cases). During the study, the fidelity of counseling and counselors’ adherence to the manual was monitored via regular group supervision sessions involving the study team in China, as well as via conference calls and occasional visits by the author of the BDRC manual (MCC).

2.4. Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures, specified in advance, were reductions in self-reported HIV risk behaviors, reductions in illicit opiate use, and treatment retention. The short version of AIDS Risk Inventory, assessing drug-related and sexual risk behaviors associated with HIV transmission (Chawarski et al., 1998), was administered at baseline and 3 and 6 months after study enrollment. A Mandarin Chinese version of this assessment, translated by native Mandarin Chinese-speaking co-investigators in previous studies in Malaysia and China and then back translated and checked for accuracy and equivalence, has been used in several previous studies (Chawarski et al., 2008, Schottenfeld at al., 2008). Illicit drug use was measured by at least monthly urine testing using rapid/instant urine tests for opiates (morphine). Treatment retention was defined as continuing to receive methadone treatment at 6 months.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups were compared using the chi-square and t-test as appropriate. Changes in self reported HIV risk behaviors and in illicit opiate use were analyzed using a MIXED Models repeated measures analysis of variance procedure evaluating between group differences (Standard MMT vs. MMT + BDRC), time effects (baseline, 3 months, 6 months) and their interaction. Treatment retention was evaluated by comparing proportion of patients remaining in MMT treatment at 6 months.

Statistical analyses were planned in advance, and all randomized patients were included in the analyses.

3. Results

There were no significant baseline differences between the two groups on demographic or drug use characteristics, including mean (SD) age (37.0 (7.5) and 36.4 (7.0) years) and the proportions male (88%, 75%), with less than high school education (71%, 90%), unemployed (47%, 75%), married (35%, 35%), or with current IDU (88%, 70%), for the standard MMT or MMT+BDRC groups, respectively.

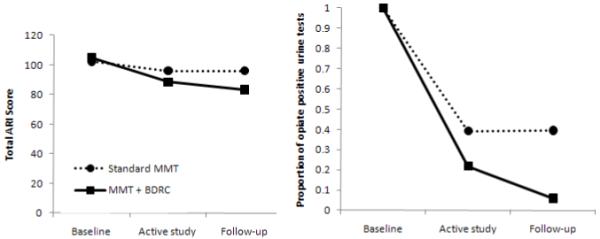

Both groups significantly reduced HIV risk behaviors from baseline (F(2, 65)=33.13, p<0.001), and the reductions were significantly larger for the MMT+BDRC group than for the Standard MMT group (F(2, 65)=7.17, p<0.01) (Figure 1, left panel). Although both groups also significantly reduced opiate use from baseline (F(2, 74)=206.21, p<0.001), the overall reduction of opiate use over time was significantly greater in the MMT+BDRC group than in the Standard MMT group (F(2, 74)=7.18, p<0.001) (Figure 1, right panel).

Figure 1.

Changes in HIV risk behaviors (left panel) and reductions in illicit opiate use (right panel) during the active study phase and the follow-up

Retention in MMT at six months was 80% in the MMT+BDRC group and 76% in the standard MMT group (p=0.8).

4. Discussion

The results of this pilot randomized clinical trial support the feasibility and potential efficacy of providing behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (BDRC) in MMT programs in China. HIV risk behaviors and illicit opiate use decreased over time for both groups, and the reductions were significantly greater for patients who were provided BDRC in addition to standard MMT services.

BDRC focuses on a limited number of problem areas and offers a prescriptive approach for addressing specific key problems with short-term goal-setting and behavioral contracts. With good efficacy when provided by nursing or other medical personnel who do not have advanced training in psychology or social work, BDRC seems particularly suitable for China and other developing countries where masters or doctoral level therapists are not available. For this study, all four nurses who initiated training completed the didactic sessions, provided BDRC with at least satisfactory proficiency to two patients under close supervision, and provided BDRC in the pilot randomized clinical trial. The relative ease of recruiting and training nurses in Wuhan to provide BDRC supports the feasibility of providing BDRC as part of routine MMT.

Some limitations of this pilot study include the small sample size, the relatively low dose of methadone provided to participants in both treatment groups, the potential variability of the treatment as usual provided to all participants (since we did not tightly control the standard MMT services provided to participants), the absence of a control for time and attention between the two randomized groups, and infrequent urine sample collection.

The study results support the efficacy of BDRC, even though the counselors in the study had only minimal previous experience in counseling approaches generally or more specifically in drug counseling for opiate dependent individuals. We might anticipate that outcomes with BDRC would become even better as counselors develop greater experience providing it. MMT reduces illicit opioid use and HIV risk behaviors, but providing specialized counseling (BDRC) may improve its effectiveness. Replication of these results in a larger study in China enrolling a more diverse sample of patients; identification of specific patient subgroups that do or do not need (or respond to) enhanced services; and evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the components of enhanced or standard services are all needed to improve evidence-based guidelines for MMT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chawarski MC, Mazlan M, Schottenfeld RS. Behavioral drug and HIV risk reduction counseling (BDRC) with abstinence-contingent take-home buprenorphine: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarski MC, Pakes J, Schottenfeld RS. Assessment of HIV risk. J Addict Dis. 1998;17:49–59. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Wu Z, Duc TT, Stephens D, Sullivan S, Liu W, Chen Y, Ngu D, Des Jarlais DC. ‘Social evils’ and harm reduction: the evolving policy environment for human immunodeficiency virus prevention among injection drug users in China and Vietnam. Addiction. 2007;103:137–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JT, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Wang N, Lau M, Tsui HY, Zhang J, Cheng F. Changes in the prevalence of HIV-related behaviors and perceptions among 1832 injecting drug users in Sichuan, China. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:325–35. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181614364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Wang X. Drug addiction in China. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1141:304–317. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Fang Y, Wang X. Drug abuse in China: Past, present and future. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:479–490. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Zhao D, Bao YP, Shi J. Methadone maintenance treatment of heroin abuse in China. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2008;34:127–31. doi: 10.1080/00952990701876989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Narcotic Control Commission . Annual Report on Drug Control in China. Beijing: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pang L, Hao Y, Mi G, Wang C, Luo W, Rou K, Li J, Wu Z. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):103–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P. Shaping Perceptions to Motivate Healthy Behavior: The Role of Message Framing. Psychol Bull. 1997;121:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ, Salovey P, Antone C, Keough K, Martin DC. The Influence of Message Framing on Intentions to Perform Health Behaviors. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1993;29:408–433. [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld RS, Chawarski MC, Mazlan M. Maintenance treatment with buprenorphine and naltrexone for heroin dependence in Malaysia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2192–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60954-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SG, Wu Z. Rapid scale up of harm reduction in China. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YL, Hao W. Improving drug addiction treatment in China. Addiction. 2007;102:1057–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Overview of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, scientific research and government responses in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):3–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304690.24390.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang N, Wang L, Li D, Jia M, Gao X, Qu S, Qin Q, Wang Y, Smith K. The 2007 Estimates for People at Risk for and Living With HIV in China: Progress and Challenges. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2009;50:414–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]