Abstract

Phenotypes that might otherwise reveal a gene’s function can be obscured by genes with overlapping function. This phenomenon is best-known within gene families, where an important shared function may only be revealed by mutating all family members. Here we describe the ‘Green Monster’ technology enabling the precise deletion of many genes. In this method, a population of deletion strains with each deletion marked by an inducible green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, is subjected to repeated rounds of mating, meiosis, and flow-cytometric enrichment. This results in the aggregation of multiple deletion loci within single cells. The Green Monster strategy is potentially applicable to assembling other engineered alterations in any species with sex or alternative means of allelic assortment. To demonstrate the technology, we generated a single broadly drug-sensitive strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae bearing precise deletions of all 16 adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporters within clades associated with multi-drug resistance.

Introduction

Robustness of biological systems to genetic insults is widespread. Synergistic sick or lethal interactions are observed for over 75% of non-essential genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae1,2. Moreover, interactions involving three or more genes (for example, the seven-gene genetic interaction involving oxysterol binding protein genes3) are likely to outnumber pairwise genetic interactions1. Gene families with members related by sequence may frequently harbor a multi-gene interaction, but few of the 80 yeast gene families with six or more genes (Supplementary Table 1 online)4 have been entirely deleted to identify important underlying shared functions.

Functional redundancy complicates pharmaceutical development. For example, adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette (ABC) transporters overlap in the drugs they export. To isolate the activities of individual transporters, a yeast strain (AD12345678; hereafter termed “AD”) was generated with mutations in nine genes, including seven ABC transporter genes 5. This strain is hypersensitive to many compounds, facilitating many studies of drug mechanism6 and offers a simplified genetic background for characterizing exogenous transporters7. However, the two ABC transporter gene clades implicated in drug efflux contain a total of 16 genes8,9, motivating further deletions within this family.

In yeast, gene deletion is accomplished by replacement with a selectable marker via homologous recombination10. However, engineering strains bearing many unlinked deletions presents challenges: (1) If deletions are sequentially introduced, the time required scales linearly with the number of target genes. (2) If specific subsets of deletions are lethal in combination, different ‘dead ends’ may be reached depending on the order of deletion, so that achieving the greatest tolerable number of deletions may be impracticable. (3) Finally, there are a limited number of useful selectable markers.

All commonly used methods suffer from the first two problems, but some have addressed the third by removing markers before re-use. Unfortunately, each marker-removal method has additional problems. In the hisG method, flanking bacterial hisG sequences recombine to excise the deletion cassette11, but remnant hisG sequences accumulating in the genome cause mistargeting of subsequently introduced knock-out fragments12,13. The Cre/lox method improves marker excision efficiency and leaves a shorter remnant sequence14,15. However, Cre recombinase also catalyzes massive genome rearrangements between non-adjacent loxP sites (E. Boles, personal communication 15,16. In the ‘delitto perfetto’ method, a short fragment with homology specific to each locus is used for excision of each marker17. Because yeast transformation is required twice per cycle, this method is time-consuming. Here we describe the ‘Green Monster’ technology which addresses all three problems. Using this technology, we generated broadly drug-sensitive ‘ABC16-monster’ strains lacking 16 ABC transporter genes in clades implicated in multi-drug resistance.

RESULTS

The Green Monster strategy

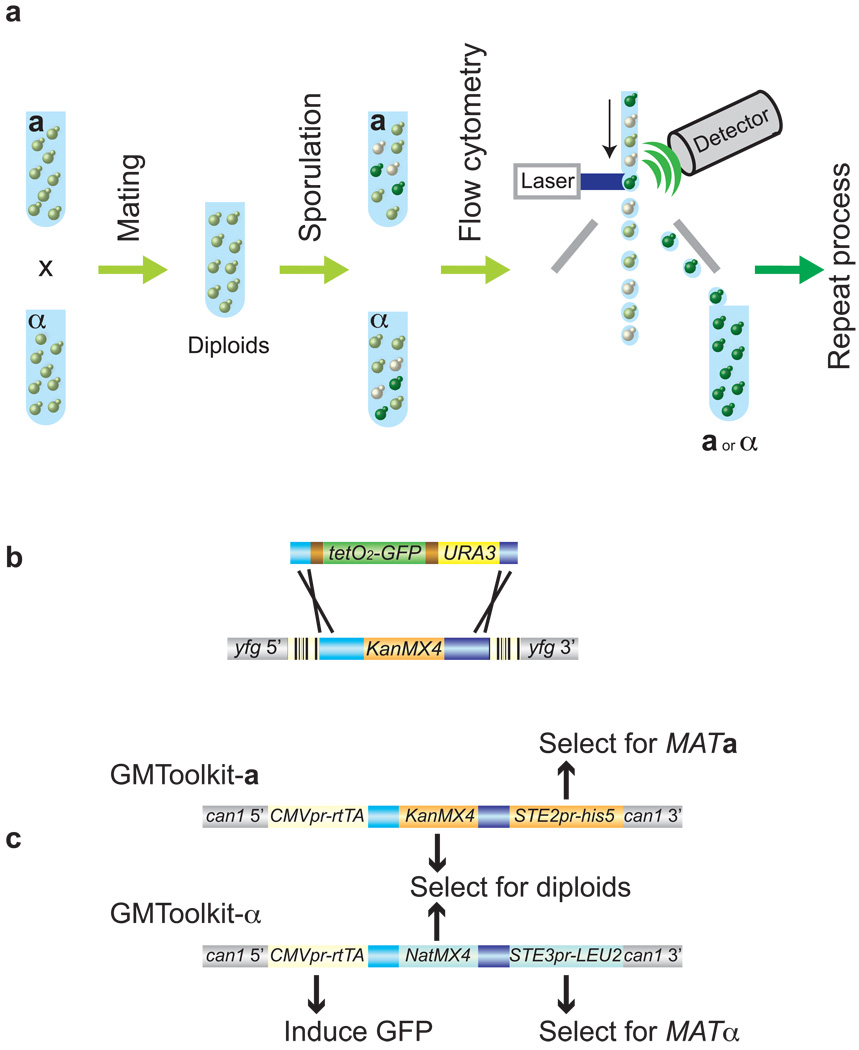

The core idea of the Green Monster strategy is that multiple genetic alterations—each constructed in a separate strain and each labeled with a quantitatively selectable marker such as the green fluorescent protein (GFP)—can be assembled into a single strain. Assembly is done via repeated rounds of sexual assortment and enrichment of progeny bearing an ever-increasing number of altered loci (Fig. 1a). The strategy is general to any species for which individual loci can be engineered and marked to allow selection or efficient screening on the basis of gene dosage, and alleles can be reassorted via mating or its equivalent (such as viral transfection or bacterial conjugation). Here we implement the strategy for the yeast S. cerevisiae.

Figure 1.

Design of the Green Monster process. (a) Schematic overview of the process In yeast, crossing different haploid single-mutants generates 0-deletion (off-white), 1-deletion (light green), and 2-deletion (dark green) cells. From this mixture, flow cytometry enriches for 2-deletion cells. Higher-order multi-mutants are assembled via repeated rounds of sexual assortment and enrichment. (b) Universal GFP deletion cassette replaces KanMX4 in 'your favorite gene' (YFG) via recombination within TEF subsequences, while maintaining barcodes (stripes) intact. The inducible tetO2 promoter allows titration of GFP expression. Transcriptional terminators (brown) and the TEF promoter (light blue) and terminator (dark blue) are shown. Selectable marker: URA3.. (c) GMToolkits, inserted at the CAN1 locus, contain rtTA21, either KanMX4 and STE2pr-Sp-his5 (GMToolkit-a) or NatMX4 20 and STE3pr-LEU2 19 (GMToolkit-α).

The initial ingredient is a set of ‘ProMonster’ strains, each carrying an identical inducible GFP reporter replacing one of the target genes (‘your favorite genes’ or YFGs; Fig. 1b). To facilitate repeated sexual assortment of these deletions, ProMonsters of mating types (MATs) a and α carry the GMToolkit-a and GMToolkit-α constructs, respectively, at the CAN1 locus (Fig. 1c). Each GMToolkit contains: (1) one of two markers allowing selection of haploids of the appropriate mating type—either Schizosaccharomyces pombe his5 (known to complement S. cerevisiae his3 mutations)18 under the control of the MATa-specific STE2 promoter, or LEU2 driven by the MATα-specific STE3 promoter19; (2) one of two drug-selectable markers—either KanMX4 conferring resistance to G418 (G418R) or NatMX4 conferring resistance to nourseothricin (NatR)20— collectively allowing selection for MATa/MATα diploid cells carrying both GMToolkits, and (3) the Tet activator rtTA21 for GFP induction enabling flow cytometric enrichment. Deletion strains can either be pooled (in the en masse process) or be isolated and genotyped before each cross to maintain specific deletions with reduced fitness in the population.

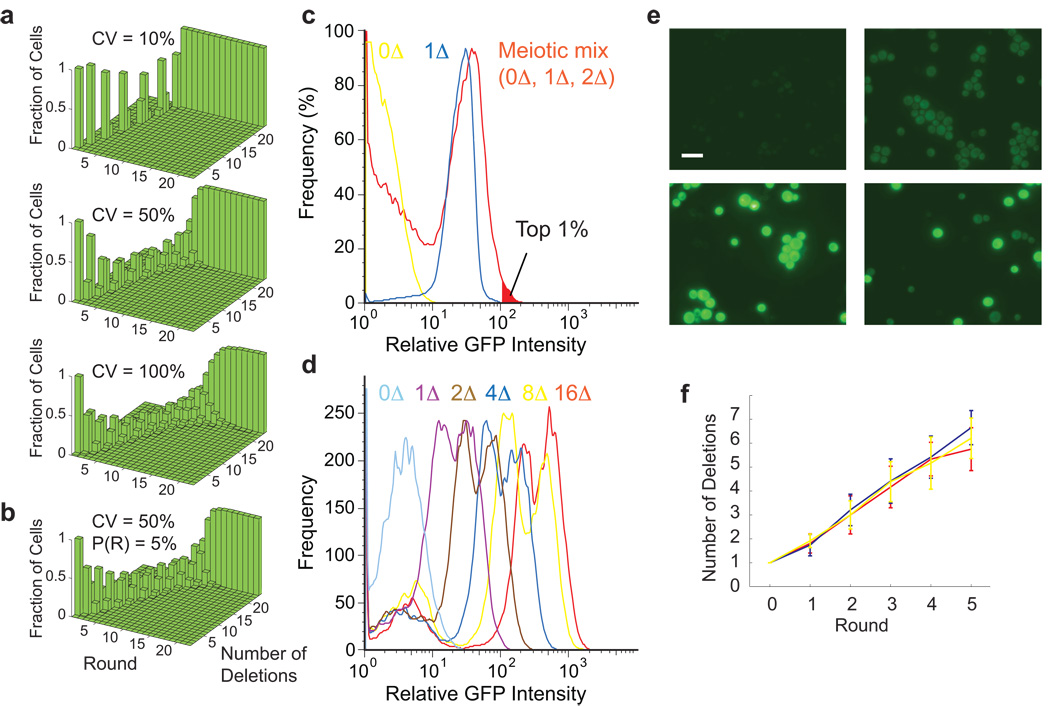

Simulation of the Green Monster process

GFP intensity varies even within isogenic cell populations. To gauge the impact of this variation on our ability to separate cells by GFP gene dosage, we performed Monte Carlo simulations of the en masse process. Simulations initiated with 24 ProMonsters of each mating type yielded a population with 99% of cells deleted in all 24 genes in 12 rounds (Fig. 2a). It may seem counterintuitive that cells carrying 24 GFP copies could be separated from cells carrying 23 GFP copies when GFP expression at each locus can vary amongst cells by 50%; however, the extreme high-intensity tail of the distribution should be dominated by the cells carrying the most GFP copies.

Figure 2.

Demonstration of the Green Monster process. (a) Simulations showing that >99% of a cell population accumulate all 24 deletions in eight (top), 12 (middle), or 19 rounds (bottom), with greater efficiency for lower coefficient of variation (CV) of GFP intensity (achievable using internal standard to control for noise (b) Simulation showing that 24 linked deletions with the meiotic crossover probability between adjacent loci (P(R)) of 5% can assemble in 16 rounds when the GFP CV is 50%. (c) Cell sorting strategy. Histograms (y-axis: the percentage of maximum cell number) are shown for GFP intensity in no-GFP cells (0Δ), single-GFP cells (1Δ), and a haploid ‘meiotic mix’ resulting from a cross of two single-GFP strains, with an expected 1:2:1 ratio of no-GFP, one-GFP, and two-GFP cells. The brightest 1% of the cells in the meiotic mix were collected (red filled area). (d) GFP intensity of multi-mutants. Histograms are shown for no-GFP, 1-GFP, 2-GFP, 4-GFP, 8-GFP and 16-GFP ‘ABC16-monster’ cells (isogenic populations). (e) Fluorescence micrographs showing non-mutant (top left), double-mutant (top right), the ABC16-monster (bottom left), and a mixture of double mutant and ABC16-monster (bottom right) cells. Identical exposure, brightness, and contrast settings were used for images. Scale bar indicates 10 µm. (f) The en masse Green Monster process. Average deletion numbers for each round from three independent processes are plotted (red, blue, and yellow). Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 21 – 34).

To combine deletions on the same chromosome, a meiotic crossover must occur between deleted loci. When simulating an extreme case where all deletions are on one chromosome spaced ~15 kb apart, the final multi-mutant dominated the population in 16 rounds (Fig. 2b), as opposed to 12 rounds if each deletion locus were independently assorting. Therefore, genetic linkage between deletion loci is not problematic (and may be an advantage in later rounds in that, once linked, altered loci will tend to stay together).

Generating and testing Green Monster reagents

To implement the Green Monster strategy, we constructed universal tetO2pr-GFP deletion cassettes (Fig. 1b), as well as GMToolkit-a and GMToolkit-α (Fig. 1c). Given the existing library of KanMX4 deletion strains, these cassettes enable targeting of any locus without any locus-specific reagents (by virtue of flanking sequences with homology to KanMX4). This replacement retains the barcode sequences that uniquely identify each locus in this library. In testing this strategy (Online Methods, we correctly inserted the GFP cassette in all Ura+ G418-sensitive transformants (n = 24). We also generated a cassette with HphMX420 instead of URA3. Should GFP expression saturate the production capacity of cells or become toxic, the tetO2 promoter allows GFP expression to be reduced by lowering doxycycline concentration. For essential target genes, tetO2pr-GFP cassettes can be linked to temperature-sensitive22 or other informative alleles23.

To assess each component, we mated a MATa strain carrying the HphMX4 tetO2pr-GFP cassette with MATα cells carrying both a URA3 tetO2pr-GFP cassette at a different unlinked locus and GMToolkit-α (Online Methods). The resulting diploids were then sporulated. Assuming normal meiotic segregation of two unlinked genes, we expected MATα GMToolkit-α cells selected from this meiotic mix to be a 1:2:1 mixture of no-GFP, 1-GFP and 2-GFP cells. We collected the most fluorescent cells (Fig. 2c) and genotyped them using HphMX4 and URA3 markers. Unsorted cells were 25% double-mutant (n=60) as expected, whereas sorted cells were 92% double-mutant (n=60), demonstrating selection of multi-mutants using GFP intensity.

Deleting 16 ABC transporter genes

To test the scalability of the Green Monster process, we targeted all 16 genes within the ABCC and ABCG clades in the S. cerevisiae ABC transporter family (these clades contain multiple genes associated with multi-drug resistance)8,9. For each of the 16 targets, we generated both MATa and MATα ProMonster strains. When we combined all strains in a pool and treated them with one round of the process (Supplementary Fig. 1 online), 100% (n=12) of the resultant haploids were double mutants (~25% would be expected from random segregation). Genotyped double-mutant strains were crossed—either in pools or individually—with opposite mating-type strains (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 online). In 16 out of 21 crosses throughout the lineage, the average number of deletions in sorted strains exceeded the number expected for unsorted strains (Supplementary Table 2 online). This measure of enrichment is conservative in that expectations did not account for potential under-representation of higher-order mutants due to reduced fitness. Because many crosses can proceed in parallel, the total time required scales not with the total number of crosses, but with the greatest number of rounds in any lineage from ProMonster to the final multi-mutant.

We obtained ‘ABC16-monsters’ with all 16 transporter genes deleted with no more than 11 rounds along any lineage. Because each round of the Green Monster process requires 13 days (Online Methods), 143 days would thus be sufficient for construction of the ABC16-monsters given this protocol,. We estimate that the Green Monster process reduced the time required for strain construction using the hisG, Cre/lox, or delitto perfetto method by about 40%, without taking into account other limitations of these approaches (Online Methods). We confirmed both the absence of coding sequences and the presence of the deletion cassette using PCR at all 16 loci. While ectopic reciprocal recombination is seen with the Cre/lox method (E. Boles, personal communication)15,16, the ABC16-monster had no recognizable karyotype defects (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Consistent with the absence of ectopic rearrangement, PCR primers external to the deletion cassette loci for each of the targeted loci amplified fragments of the expected size (Supplementary Fig. 4 online; Online Methods). Analysis of the ABC16-monster and other strains showed a near-linear correlation between fluorescence intensity and number of deletions, both in flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 2d) and in micrographs (Fig. 2e). The level of GFP expression in these cells—even with high levels of the inducer doxycycline—did not affect growth rates (Supplementary Table 3 online).

To confirm the effectiveness of flow cytometry in enriching for strains with more than a few deletions, we crossed the ABC16-monster with a non-mutant strain, and genotyped both sorted and unsorted haploid progeny resulting from one round of the Green Monster process. By sorting the 1% brightest cells, we obtained a greater average of 9.6 ± 0.3 (s.e.m.) deletions (n = 24 for all samples), as compared with 7.6 ± 0.5 deletions for the unsorted sample (P = 0.002). Sorting the top 0.1% of cells achieved an average deletion number of 10.3 ± 0.4 (P = 0.0002).

To evaluate the generality of the Green Monster process, we applied it to assemble another ‘Green Monster’ comprising deletions in six genes that are unrelated to ABC transporters: YER042W, YCL033C, YDL242W, YDL227C (HO), YKL069W, and YOL118C (V. M. L. and V. N. G., unpub. data). We completed the generation of this six-deletion strain in three rounds (Supplementary Table 4 online). Because YDL242W and YDL227C are separated by only 27 kb, we used these loci to assess whether recombination is elevated between nearby deletion cassettes. PCR using primer pairs external to each GFP cassette yielded bands of the expected sizes, whereas PCR designed to detect a cassette-mediated recombination between loci did not detect any rearrangement (Supplementary Fig. 5; Methods).

Evaluating the en masse Green Monster process

The processes described above exploited both GFP fluorescence and genotyping to enrich for multi-mutants. To evaluate the Green Monster process as implemented without the benefit of enrichment via genotyping, we carried out three independent lines of the process (Supplementary Fig. 6 online), such that heterogeneous pools of deletion strains emerging from each fluorescence-based selection were taken directly into the next round and mated together en masse. The Green Monster process was highly efficient in selecting the correct cell type (haploid or diploid) in each step (Supplementary Table 5 online). To monitor progress in terms of number of deletion alleles, we genotyped a sample of strains from the sorted pools. The average deletion numbers ascended in each round to reach six in only five rounds of the Green Monster process (Fig. 2f; Supplementary Table 6 online). Moreover, the final populations included eight- and nine-deletion strains. The rapid en masse option for allele assembly without isolating and genotyping strains can reduce each round time from 13 to 11 days and reduce the number of processes that are run in parallel. It could be widely applicable, particularly where multi-mutant fitness effects are limited. Single-mutant fitness defects are limited for the majority of deletions24, and can be further limited via the use of reduced-function23, conditional22 alleles, or by ectopic expression of target genes during strain construction. However, PCR-based genotyping can maintain the presence of alleles with reduced fitness or fluorescence intensity, is not labor-intensive, and reveals progress during the process.

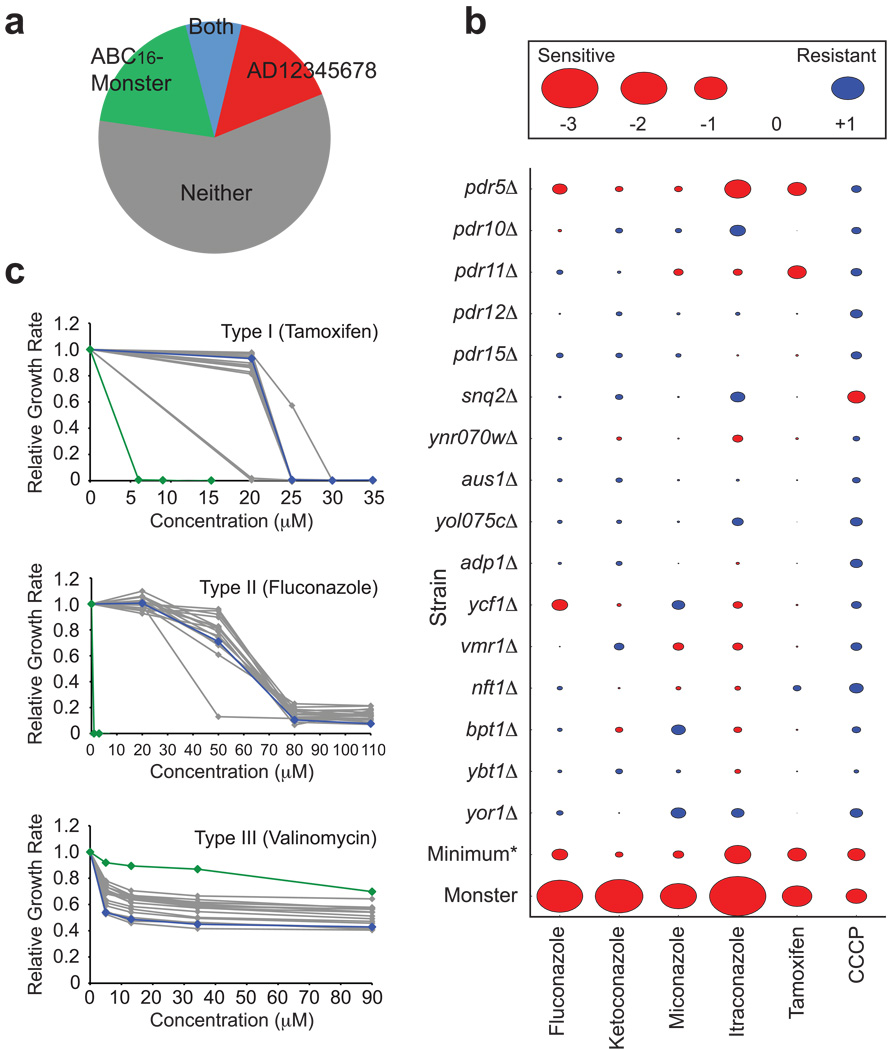

Demonstrating drug sensitivity for ABC16-monsters

To compare drug sensitivity of the ABC16-monster with the previous drug-hypersensitive AD strain5, we measured drug sensitivity in response to a panel of ~400 drugs previously used in human clinical trials (NIH Clinical Collection; Supplementary Table 7 online). The ABC16-monster exhibited sensitivity to a comparable number of drugs as the AD strain (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table 8 online). The strains were complementary in that, for 34% of all drugs tested, only one of the two hypersensitive strains exhibited sensitivity.. The ABC16-monster should, for example, be particularly useful for studying the mechanisms of action for clotrimazole, benidipine, cisapride, and perospirone, each of which inhibited the growth of the ABC16-monster by more than 75%, but had little effect on the growth of AD (Supplementary Table 8 online). Resistance to some drugs, observed for both AD and ABC16-monster strains (e.g., carmofur and rimcazole), may arise from deletion of one transporter gene that triggers resistance via compensatory upregulation of other transporters25.

Figure 3.

Hypersensitivity of the ABC16-monster to drugs. (a) Pie chart showing the number of drugs to which the ABC16-monster or the previously-described drug-hypersensitive AD strain is more sensitive. (b) A comparison of ABC16-monster and single-mutant drug sensitivity. The IC50 for each strain/drug combination relative to that of the corresponding non-mutant/drug combination was calculated. Area of each shape is proportional to this relative IC50 value. *: The minimum value among the relative IC50 values for single mutants is indicated for comparison with the relative IC50 of the ABC16-monster (c) Exponential growth rates of the ABC16-monster (green), non-mutant (blue), and single-deletion strains (grey) as a function of concentration of tamoxifen, fluconazole, and valinomycin.

To evaluate the effects of eliminating multiple genes with overlapping function (‘multi-gene redundancy’), we compared IC50 values of the ABC16-monster with those of single mutants for compounds previously used7 to characterize ABC transporters (Fig. 3b, c; Supplementary Table 9; Methods). At least three patterns of drug response emerge.

In the first pattern, exemplified by tamoxifen and carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), the ABC16-monster was more sensitive than non-mutant and most single-mutant strains tested, but on par with the most sensitive single mutant. This suggests the existence of one or two major transporters for each drug (e.g., Pdr5p and Pdr11p for tamoxifen and Snq2p for CCCP, based on Fig. 3b), with little compensatory activity provided by the other transporters.

The second drug response pattern is exemplified by fluconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, and itraconazole. The ABC16-monster was highly sensitive, similarly to the AD strain7, while single mutants other than pdr5Δ did not have marked sensitivity (Fig. 3b, c). This suggests that transporters beyond Pdr5p are involved in transporting these drugs, such that the effect of deleting each transporter alone is diminished by overlapping activity among the others. The fitness of the ABC16-monster was lower than expected from a multiplicative model of independent effects26 across a range of concentrations for each of these azole drugs, indicating synergistic genetic interaction (Supplementary Table 10 online).

The third pattern of drug response was represented by valinomycin, an ionophore that disrupts mitochondrial function. The ABC16-monster was unexpectedly more resistant than non-mutant or any single mutant to valinomycin (Fig. 3c). Since thirteen single mutants had slight resistance compared to non-mutant cells, the monster may simply have the aggregated effects of single deletions. Previously, increased resistance in ABC-transporter deletion strains was observed for substrates of Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Yor1p25. In this previous example, specific efflux pumps responsible for the resistance were already known. However, our deletion of 16 single mutants potentially defective in drug transport did not reveal an obvious candidate transporter for valinomycin. Potential mechanisms include compensatory upregulation of other proteins capable of valinomycin transport, (for example, antiporters of the major facilitator superfamily) and import of valinomycin by two or more ABC transporters, as suggested for other substrate-transporter combinations27.

Taken together, our analysis of drug sensitivity in ABC16-monsters shows that the removal of confounding activities in large gene families with overlapping function can reveal phenotypes that would be otherwise obscured.

DISCUSSION

The Green Monster process was enabled by quantitative markers such as GFP that allow simultaneous selection for the presence of multiple altered loci. Markers that permit selection for gene dosage have been employed to select for segmental amplification at a given locus, but not to select for alleles at multiple distinct loci. The marker system used in the Green Monster process to ‘drive’ cells through the sexual cycle may enable other studies, such as laboratory evolution using a sexually recombining cell population.

Illustrating the potential value of this technology, an ABC16-monster strain we constructed is complementary to a previous drug hyper-sensitive strain (AD) in that it reveals sensitivity that is not present in either wild-type or the AD strain for 19% of all drugs tested. ABC16-monster strains should facilitate characterization of diverse compounds that are efficiently exported from wild-type or AD yeast cells. Somatic or germline mutations in at least ten human ABC transporter genes affect drug sensitivity28. Yeast has proven to be useful for characterizing polymorphisms in the human ABCB1 gene29. Given that most known human drug transporters belong to the ABCC or ABCG subfamilies that were entirely deleted in the ABC16-monster, this strain provides a cleaner genetic background for identifying human ABC transporter substrates or inhibitors.

The Green Monster process has advantages not found in some other technologies for strain construction: it can engineer multiple loci in each round; it can avoid local maxima in the number of tolerable deletions by sampling many construction paths in parallel; and it circumvents constraints imposed by the limited number of useful selectable markers. The process of assembling Green Monsters yields many more intermediate strains than would be produced in more linear construction approaches. These intermediate strains could prove useful for exploring complex genotype-phenotype relationships.

The Green Monster process shares limitations with all other strategies. Where genes are essential (either individually or in combination) the process cannot proceed without the use of hypomorphic, conditional, or ectopically-expressed ‘covering’ alleles. Like other methods, it is subject to the appearance of adaptive mutations. However, the Green Monster process may be less subject to aneuploidies (present in at least 8% of deletion strains30), given that the strains it produces must repeatedly survive meiosis.

The Green Monster process has limits not shared by other methods. Combining otherwise-viable deletions in genes required for mating, sporulation, or GFP expression will be problematic. The total number of such genes is unknown but we expect is fewer (perhaps much fewer) than 15% of all genes. We saw no evidence for ectopic recombination after isolation of the original colony, outgrowth to generate a frozen glycerol stock, and subsequent thawing and outgrowth for analysis of genomic integrity. However, Green Monster strains are in theory more susceptible to ectopic recombination so that strains should be examined periodically for instability.

The core requirements of the Green Monster technology—a quantitatively selectable marker and the ability to combine alleles through sexual assortment or its equivalent—are met by many species. Although the specific schemes will necessarily differ, we can already envision application of the strategy in three important model organisms (Supplementary Fig. 7 online provides an overview in E. coli, C. elegans, and mouse).

Finally, the Green Monster strategy could be readily extended to allow insertion of exogenous genes, and therefore permit the construction of exogenous or synthetic pathways in yeast or other model organisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants R01 HG003224 and R21 CA130266 to F.P.R. O.D.K. was supported by an NRSA Fellowship from the NIH/NHGRI. Micrographs were generated at Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School. We are grateful for yeast strains from C. Boone (University of Toronto) and A. Goffeau (Université catholique de Louvain), and for advice and assistance from M. Al-Shawi, B.J. Andrews, C. Baisden, R. Balasubramanian, W. Bender, C. Boone, R. Brost, S. Buratowski, D. Chowdhury, G. M. Church, D. Coen, E. Craig, E. Elion, M. Fenerjian, D. Gibson, J. Glass, A. Goffeau, R. Grene, C. Hutchison, S. Iwase, M. Johnston, B. Karas, K. Kono, K. Kuchler, J. Li, D. Morgan, S. Moye-Rowley, J. Murai, S. Oliver, F. Ozbek, Y. Pan, D. Pellman, A. Ramon, J. Rine, A. Rowat, P. Silver, H. Smith, M. Springer, K. Struhl, C. Tagwerker, M. Takahashi, B. Turcotte, D. Weitz, and S. Yoshida. We also thank members of the Roth Lab, especially M. Tasan, J. Mellor, J. Komisarof, J. MacKay, A. Derti, and S. Komili, and members of the Dana-Farber Center for Cancer Systems Biology, especially P. Braun, A. Dricot, D. Hill, Q. Li, and H. Yu.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Y. S. and F. P. R., Green Monster method development and manuscript preparation; R. P. St. O., A. H., J. L., and Y. S., drug sensitivity measurement; R. M., growth curve analysis; O. D. K., simulation of the process; L. V. Z., C. N., and G. G., advice on method design; A. H. Y. T., V. M. L., V. N. G., and M. V., reagents and advice; W. C. and L. P., technical support; P. S. and Y.S., flow cytometry.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT: The authors have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tong AH, et al. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science. 2004;303:808–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1091317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costanzo M, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beh CT, Cool L, Phillips J, Rine J. Overlapping functions of the yeast oxysterol-binding protein homologues. Genetics. 2001;157:1117–1140. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pruess M, et al. The Proteome Analysis database: a tool for the in silico analysis of whole proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:414–417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decottignies A, et al. ATPase and multidrug transport activities of the overexpressed yeast ABC protein Yor1p. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12612–12622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Entwistle RA, Winefield RD, Foland TB, Lushington GH, Himes RH. The paclitaxel site in tubulin probed by site-directed mutagenesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae beta-tubulin. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2467–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura K, et al. Functional expression of Candida albicans drug efflux pump Cdr1p in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain deficient in membrane transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3366–3374. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3366-3374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decottignies A, Goffeau A. Complete inventory of the yeast ABC proteins. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:137–145. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst R, Klemm R, Schmitt L, Kuchler K. Yeast ATP-binding cassette transporters: cellular cleaning pumps. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:460–484. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothstein RJ. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alani E, Cao L, Kleckner N. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics. 1987;116:541–545. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.541.test. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akada R, et al. PCR-mediated seamless gene deletion and marker recycling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2006;23:399–405. doi: 10.1002/yea.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson JF, Schiestl RH. Mis-targeting of multiple gene disruption constructs containing hisG. Curr. Genet. 2000;38:188–190. doi: 10.1007/s002940000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guldener U, Heck S, Fielder T, Beinhauer J, Hegemann JH. A new efficient gene disruption cassette for repeated use in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2519–2524. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delneri D, et al. Exploring redundancy in the yeast genome: an improved strategy for use of the cre-loxP system. Gene. 2000;252:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wieczorke R, et al. Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:123–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01698-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storici F, Lewis LK, Resnick MA. In vivo site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:773–776. doi: 10.1038/90837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wach A, Brachat A, Alberti-Segui C, Rebischung C, Philippsen P. Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast (Chichester, England) 1997;13:1065–1075. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1065::AID-YEA159>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Boone C. In: Methods in Microbiology. Stansfield I, Stark MJR, editors. Vol. 36. Elsevier Ltd.; 2007. pp. 369–386.pp. 706–707. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein AL, McCusker JH. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast (Chichester, England) 1999;15:1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gossen M, et al. Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science (New York, N.Y. 1995;268:1766–1769. doi: 10.1126/science.7792603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Aroya S, et al. Toward a comprehensive temperature-sensitive mutant repository of the essential genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow DK, et al. A comprehensive strategy enabling high-resolution functional analysis of the yeast genome. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:711–718. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winzeler EA, et al. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science. 1999;285:901–906. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolaczkowska A, Kolaczkowski M, Goffeau A, Moye-Rowley WS. Compensatory activation of the multidrug transporters Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Yor1p by Pdr1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St Onge RP, et al. Systematic pathway analysis using high-resolution fitness profiling of combinatorial gene deletions. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:199–206. doi: 10.1038/ng1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;10:218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dean M. ABC transporters, drug resistance, and cancer stem cells. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2009;14:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeong H, Herskowitz I, Kroetz DL, Rine J. Function-altering SNPs in the human multidrug transporter gene ABCB1 identified using a Saccharomyces-based assay. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes TR, et al. Widespread aneuploidy revealed by DNA microarray expression profiling. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:333–337. doi: 10.1038/77116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brachmann CB, et al. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast (Chichester, England) 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belli G, Gari E, Piedrafita L, Aldea M, Herrero E. An activator/repressor dual system allows tight tetracycline-regulated gene expression in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:942–947. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gossen M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urlinger S, et al. Exploring the sequence space for tetracycline-dependent transcriptional activators: novel mutations yield expanded range and sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:7963–7968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.