Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine the role of spousal bereavement and positive emotion in naturally occurring levels of daily cortisol.

Methods

Analyses were conducted using data from the Midlife in the United Sates (MIDUS) survey and the National Study of Daily Experiences (NSDE). Baseline assessments of extraversion, neuroticism, trait positive emotion, and trait negative emotion were obtained, as were reports of demographic and health behavior covariates. Salivary cortisol levels were measured at wakeup, 30 min after awakening, before lunch, and at bedtime on each of four successive days.

Results

Multilevel growth curve analyses indicated that independent of age, gender, education, extraversion, neuroticism, negative emotion, medication use and smoking, spousal bereavement was associated with lower levels of cortisol at wakeup and a flattening of the diurnal cortisol rhythm. Mediation analyses revealed that prospective changes in positive emotion accounted for the impact of bereavement on diurnal cortisol slopes.

Conclusion

The current prospective study is among the first to provide evidence for a role for positive emotion as a mechanism by which bereavement influences HPA-axis dysregulation in older adults.

Keywords: bereavement, positive emotion, diurnal cortisol, spousal loss

The death of a spouse or life partner is associated with increase prevalence of physical illness and psychiatric morbidity, as well as excess risk of mortality in later adulthood (Christakis & Allison, 2006; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). Accumulating evidence suggests that the health consequences of bereavement are associated with changes in underlying neuroendocrine stress response systems, particularly the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. More specifically, bereavement has been linked with various patterns of cortisol dysregulation, including increased stressor reactivity, lower cortisol awakening responses, and attenuated cortisol diurnal slopes (Hagan, Luecken, Sandler, & Tein, 2010; Luecken, 1998; Meinlschmidt & Heim, 2005). Alterations in HPA-axis function resulting from bereavement, in turn, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g., Pfeffer, Altemus, Heo, & Jiang, 2009; Tyrka, et al., 2008). Despite findings of a link between bereavement and changes in HPA-axis activity, the emotion regulatory mechanisms by which the loss of a partner contributes to long-term patterns of cortisol dysregulation remain largely unexplored.

The current study examines the extent to which deficits in positive emotion following spousal loss contribute to cortisol dysregulation in later adulthood. Cortisol levels are typically highest in the morning upon awakening, increase, on average, 50–60% in the first 30–40 min post-awakening (the cortisol awakening response, or CAR), drop rapidly in the next few hours, and then decline gradually across the day to near-zero levels by bedtime (Kirschbaum & Hellhammer, 1989, 1994). Emerging evidence suggests a link between positive emotion and favorable diurnal cortisol functioning. For instance, naturally occurring cortisol levels, both total output and the awakening response, have consistently been shown to be lower among individuals with higher levels of trait positive emotion (e.g., Polk, Cohen, Doyle, Skoner, & Kirschbaum, 2005; Smyth, et al., 1998; Steptoe, O’Donnell, Badrick, Kumari, & Marmot, 2008; Steptoe, Wardle, & Marmot, 2005). Moreover, a recent prospective study revealed that compared with married controls, recently widowed individuals experienced a significant decline in positive emotion following spousal loss (Ong, Fuller-Rowell, & Bonanno, 2010). Deficits in positive emotion, thus, may play an important role in the pathway leading from spousal loss to diurnal cortisol dysregulation.

With respect to the neuroendocrine effects of positive emotion among bereaved adults, surprisingly few studies have been conducted. Furthermore, despite empirical research demonstrating an association between positive emotion and HPA-axis activity, evidence regarding the extent to which associations between cortisol and positive emotion are independent of negative emotion has been inconsistent (Jacobs, et al., 2007; van Eck, Berkhof, Nicolson, & Sulon, 1996). Accounting for potential confounding variables may be especially relevant in the context of bereavement research. Psychological morbidity, particularly psychological distress, increases the risk of death among recently bereaved partners independent of age or bereavement (Schulz, Beach, & Ives, 2000; Unutzer, Patrick, Marmon, Simon, & Katon, 2002). The study of bereavement and cortisol has likewise been hampered by inadequate assessment and control of demographic (e.g., age, gender), personality (e.g., extraversion and neuroticism), and health behavior covariates (e.g., smoking), which might be associated with HPA-axis dysregulation (Adam & Kumari, 2009; Almeida, Piazza, & Stawski, 2009; Luecken & Appelhans, 2006; Nicolson, 2004).

In the present study, we used prospective data from a national sample of adults to examine the relationship between positive emotion and neuroendocrine function, as measured by diurnal salivary cortisol levels, among bereaved spouses and non-bereaved controls. We tested the hypothesis that spousal bereavement is associated with variation in multiple parameters of diurnal cortisol activity, including lower levels of cortisol at wakeup, higher cortisol awakening responses (CAR), and flatter cortisol slopes across the waking day. Additionally, we examined a potential mechanism that may account for the relationship between spousal bereavement and disruptions in the abovementioned parameters characterizing the diurnal cortisol rhythm. We hypothesized that the effect of spousal loss on each cortisol parameter (wakeup level, CAR, diurnal slope) would be mediated by pre- to post-loss changes in positive emotion.

Methods

The data for this study are from (a) the National Survey of Midlife Development (MIDUS), a two-wave panel survey of adults between the ages of 25 and 74 in 1994/1995 in the coterminous United States and (b) the National Study of Daily Experiences, a telephone diary study of a representative subsample of the MIDUS survey participants. Phone interviews and self-administered questionnaires were conducted in 1995–1996 (Wave 1) and again in 2004–2006 (Wave 2). Wave 1 MIDUS data is comprised of four subsamples: a national random digit dialing (RDD) sample (n = 3,487); oversamples from five metropolitan areas (n = 757); siblings of individuals from the RDD sample (n = 950); and a national RDD sample of twin pairs (n = 1,914). A longitudinal follow-up was conducted in 2004–2006 (Wave 2). Of those who participated in Wave 1, 4,963 completed a Wave 2 telephone interview (70% response rate; 75%, when adjusted for mortality), and 81% of individuals who completed the telephone interview also completed self-administered questionnaires. A subset of participants from Wave 2 of the MIDUS (n = 2,022) was assessed in the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences, which is the source of data for the present analyses (see Almeida, McGonagle, & King, 2009 for a more detailed description).

Sample

Between 1994 and 2006, 132 adults in the sample experienced the death of a spouse. In the current study, inclusion criteria for the bereaved group consisted of individuals who were (a) widowed within three years of the follow-up interview,1 (b) unmarried at the time of recruitment in Wave 2 (2004–2006), and (c) included in the second wave of the National Study of Daily Experiences. Of the total 132 bereaved spouses, 22 met eligibility criteria; average time since loss was approximately 17.5 months (SD = 10.3 months). We compared this group of individuals (bereaved group) to a random sample of 22 continuously married controls (control group). Control participants from the Wave 1 sample were selected to match the widowed respondents in age, gender, and education. The final sample consisted of 44 (14% male) adults between the ages of 48 and 80 years (M = 65.8, SD = 8.9), with a little over a third (36%) having completed some college or more. The majority were White/Caucasian (93.2 %), with the remainder being Black/African American (4.5 %) or Other (2.3 %).

Measures

Positive and Negative Emotion

Assessments of positive emotion and negative emotion were obtained by self-administered questionnaires (Mroczek & Kolarz, 1998). Participants rated the amount of time they experienced various emotional states over the past 30 days on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). The six-item positive emotion scale (e.g., “cheerful,” “extremely happy,” “calm and peaceful”) was comprised of items from several well-validated measures of positive affect including the Affect Balance Scale (Bradburn, 1969) and General Well-Being Schedule (Fazio, 1977). The scale demonstrated excellent reliability in the MIDUS samples (Cronbach’s alpha for the six-item scale at Wave 1 and 2 was .91 and .90, respectively). Negative emotion was assessed with the following six items: “so sad nothing could cheer you up,” “nervous,” “restless or fidgety,” “hopeless,” “that everything was an effort,” “worthless” (α = .88; items were recoded so that higher scores indicated more negative emotion).

Extraversion and Neuroticism

Personality markers for extraversion and neuroticism were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). Extraversion was assessed with the following items: “outgoing,” “friendly,” “lively,” “active,” “talkative” (α = .79). Neuroticism was assessed with the items “moody,” “worrying,” “nervous,” and “calm” (α = .77; items were recoded so that the higher scores indicated greater neuroticism). These personality scales were developed from a pool of established Big Five trait adjectives (Goldberg, 1992) and have been used in a number of prior studies (e.g., Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002; Staudinger, Fleeson, & Baltes, 1999).

Salivary cortisol

Samples of salivary cortisol were collected four times on each of four successive days using salivette collection devices (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany). The cortisol collection occurred, on average, three to six months after the questionnaire assessment. Sixteen numbered and color-coded salivettes were included in the collection kit. In addition to written instructions that accompanied each collection kit, telephone interviewers reviewed the collection procedures and answered participant questions. Respondents provided 4 saliva samples per day on Days 2–5 of the 8-day study period that were later assayed for cortisol. Saliva was collected once upon awakening, 30 minutes after waking, before lunch, and at bed time. Cortisol concentrations were quantified with a commercially available luminescence immunoassay (IBL, Hamburg, Germany), with intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variations below five (Polk, et al., 2005). Compliance data on the exact time respondents provided each saliva sample was determined by both nightly telephone interviews and paper-pencil logs sent with the collection kit (see Almeida, McGonagle, et al., 2009; Almeida, Piazza, et al., 2009). Cortisol values were natural logarithmically transformed prior to analysis to correct for positive skew in the cortisol distribution.

Demographic and health behavior covariates

Prior to the telephone diary study, demographic and health behavior covariates including age, gender, education, smoking status, and medication use were obtained. Smoking status was determined by respondents identifying themselves as regular smokers as well as by the number of cigarettes individuals reported consuming on a daily basis during the study period. A dichotomous variable (0 = nonsmoker, 1 = smoker) was used as an index of smoking status.

Medication use was determined by participants reporting their current use of medications known to influence cortisol, including steroid inhalers, steroid medications, medications containing cortisone, birth control pills, other hormonal medications, and antidepressant or antianxiety medications. A dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether a participant reported taking any of the abovementioned medications (0 = did not use medications, 1 = used medications).

Analytic Strategy

A three-level hierarchical growth curve analysis (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was used to estimate latent diurnal (daytime) cortisol profiles for each person, and to examine predictors of the key parameters defining individual differences in diurnal cortisol activity. Analyses control for the effects of extraversion, neuroticism, negative emotion, demographic variables, and health behavior covariates. Use of multilevel modeling adjusts for the nonindependence of observations associated with nested data structures, thereby permitting the simultaneous modeling of the shape of the diurnal cortisol rhythm for each individual, along with an examination of day-level and person-level factors predicting differences in these rhythms (for a discussion, see Adam, 2006; Hruschka, Kohrt, & Worthman, 2005). In these models, levels of cortisol for each person at each moment was the criterion variable, and was predicted by moment-level predictors (Level 1), day-level predictors (Level 2), and person-level predictors (Level 3).

The individual growth of cortisol at time t on day i of person j is shown below in:

| [1.10] |

where

Corttij is the outcome at time t on day i of person j;

π0ij, the intercept, represents a latent estimate of each person’s average cortisol level at wake-up;

(Time Since Waking)tij reflects a latent estimate of linear change in each person’s diurnal cortisol rhythm across the day;

(Time Since Waking2)tij represents a latent estimate of the acceleration or the rate of curvilinearity in each person’s diurnal cortisol rhythm across the day;

(CAR)tij, the cortisol awakening response, reflects a latent estimate of the average magnitude of each person’s change in cortisol 30 minutes after waking.

Time of day values were expressed as number of hours since awakening for each person each day. The CAR was coded as a dummy variable (with 1 as the second cortisol sample taken approximately 30 minutes after waking and 0 for the other samples). Scaling time and the awakening response in this manner defines the intercept at the time of waking and allows for the diurnal slope to be unaffected by the magnitude of the awakening response (Adam, Hawkley, Kudielka, & Cacioppo, 2006; Adam & Kumari, 2009).

The level-2 model represents the variability in each of the level 1 intercept and growth parameters across days within individuals:

| [2.10] |

| [2.11] |

| [2.12] |

| [2.13] |

where

β00j is the mean cortisol intercept for person j;

β10j is the mean linear rate of decline in cortisol for person j;

β20j is the mean deceleration in the rate of decline in cortisol for person j;

β30j is the mean cortisol awakening (30 min post-awakening) for person j;

β31j is the mean deviation in cortisol level at wakeup time for person j;

Thus, each person’s intercept, wakeup level, response to awakening, and afternoon slope parameters on a given day, are predicted by each person’s average intercept and slope across the four days, as well as a person-centered time-varying covariate (wake-up time).

The level-3 model represents the variability among persons in each of the level 2 intercept and slope parameters. In addition to the primary predictor variables of spousal loss and pre- to post-loss changes in positive emotion, the level-3 model included extraversion, neuroticism, negative emotion, and demographic and health covariates (i.e., age, gender, level of education, smoking status, and medication use). As shown below, level-3 predictors were included in models estimating the three main criterion variables: the average level of cortisol at wakeup (β00j), the average linear slope of the diurnal cortisol curve (β10j), and the average magnitude of the cortisol awakening response (β30j).

| [3.10] |

| [3.11] |

| [3.12] |

| [3.13] |

| [3.14] |

All models were fitted using HLM software, version 6.08 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2004).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Of a possible 704 person-observations days (44 persons × 4 observations × 4 days), participants provided time-logged cortisol samples on 636 person-observations days (90%). Bereaved and non-bereaved participants did not differ significantly in their reports of baseline positive emotion, negative emotion, extraversion, neuroticism, or health behavior covariates. The first set of descriptive analyses examined the distribution of cortisol values across moments, days, and persons. These analyses are referred to as fully unconditional because no predictor variables are specified at any level. The ratio of between- to within-person variance (i.e., the intraclass correlation) for this model is ρperson=.13. Thus, most of the explainable variation in cortisol occurred at Levels 1 and 2 (within days and persons). Moreover the variance components for the intercept (u00j = .114), slope (u10j = .004), and awakening response (u30j = .034) were all significantly different from zero (p < .05), implying that there exists variations to be potentially explained by adding predictor variables to the model (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Comparison of the variance components between the fully unconditional model and the partially unconditional model (described in Equation 1.10) revealed that 72% of the total within-person variance in cortisol was accounted for by the level-1 model parameters (i.e., linear slope, quadratic coefficient, and the cortisol awakening response).

Multilevel Growth Curve Analyses

Multilevel growth curve analyses of key parameters defining the shape of the diurnal cortisol curve are presented in Table 1. The outcome of interest, cortisol level, was transformed by natural logarithm; thus the effect sizes for all coefficients can be interpreted as a percent change per one unit change in the independent variable, after applying the following transformation: B% change = [exp (Braw)] − 1 (Adam, 2006; Adam, et al., 2006). As illustrated in model 1, participants showed the expected diurnal cortisol pattern. Cortisol levels, on average, were appropriately high at wakeup (γ000 = 2.65, p < .001; equivalent to 14.11 nmol/L),2 and was followed by a 53% rise 30 min after awakening (γ300 = .423, p < .001; equivalent to 1.53 nmol/L). As expected, cortisol levels decreased throughout the day at a rate of 12% per hour at wakeup time (γ100 = −.125, p < .001; equivalent to 0.88 nmol/L), with a significant declining rate of change thereafter due to the positive quadratic effect (γ200 = .003, p < .01), reflecting a greater rate of deceleration in the diurnal cortisol slope.

Table 1.

Multilevel Growth Curve Model of Diurnal Cortisol Parameters

| Fixed Effects | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Wake-up cortisol, π0 | ||||||

| Average wake-up level, β00 | ||||||

| Intercept, γ000 | 2.647*** | .084 | 2.756*** | .083 | 2.762*** | .082 |

| Age, γ001 | .050 | .066 | .062 | .062 | .039 | .058 |

| Gender, γ002 | −.044 | .166 | −.0376 | .181 | .010 | .179 |

| Education, γ003 | −.111 | .110 | .118 | .103 | −.119 | .100 |

| Smoker, γ004 | .557* | .204 | .675** | .205 | .689** | .196 |

| Medication, γ005 | .017 | .101 | −.008 | .087 | .003 | .086 |

| Extraversion, γ006 | .071 | .076 | .101 | .077 | .105 | .073 |

| Neuroticism, γ007 | −.017 | .091 | −.037 | .084 | −.043 | .083 |

| Negative Affect, γ008 | −.244* | .109 | −.207* | .086 | −.232** | .081 |

| Spousal loss, γ009 | -- | -- | −.233* | .090 | −.266** | .086 |

| Δ in Positive Emotion, γ010 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.054 | .038 |

| Time since waking, π1 | ||||||

| Average linear slope, β10 | ||||||

| Intercept, γ100 | −.125*** | .016 | −.133*** | .017 | −.132*** | .017 |

| Age, γ101 | −.002 | .008 | −.004 | .007 | −.008 | .007 |

| Gender, γ102 | .012 | .015 | .011 | .012 | .019 | .012 |

| Education, γ103 | −.007 | .009 | −.007 | .009 | −.006 | .008 |

| Smoker, γ104 | −.007 | .020 | −.017 | .020 | −.016 | .019 |

| Medication, γ105 | −.013 | .010 | −.011 | .011 | −.009 | .011 |

| Extraversion, γ106 | −.008 | .007 | −.011 | .007 | −.010 | .007 |

| Neuroticism, γ107 | −.020 | .011 | −.018 | .011 | −.019 | .010 |

| Negative Affect, γ108 | .019* | .009 | .016 | .008 | .011 | .008 |

| Spousal loss, γ109 | -- | -- | .021* | .009 | .016 | .009 |

| Δ in Positive Emotion, γ110 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.009** | .003 |

| Time since waking squared, π2 | ||||||

| Average curvature, β20 | ||||||

| Intercept, γ200 | .003** | .001 | .003** | .001 | .003** | .001 |

| Awakening response, π3 | ||||||

| Average awakening response, β30 | ||||||

| Intercept, γ300 | .423*** | .068 | .394*** | .082 | .392*** | .081 |

| Age, γ301 | −.054 | .066 | −.060 | .067 | −.043 | .074 |

| Gender, γ302 | −.169 | .140 | −.169 | .143 | −.196 | .151 |

| Education, γ303 | .196 | .103 | .200 | .105 | .195 | .101 |

| Smoker, γ304 | −.192 | .161 | −.221 | .173 | −.221 | .174 |

| Medication, γ305 | −.063 | .103 | −.057 | .103 | −.058 | .104 |

| Extraversion, γ306 | −.107 | .075 | −.114 | .073 | −.118 | .068 |

| Neuroticism, γ307 | −.119 | .097 | −.115 | .096 | −.109 | .095 |

| Negative Affect, γ308 | .271* | .100 | .262* | .097 | .266* | .103 |

| Spousal loss, γ309 | -- | -- | .063 | .100 | .077 | .094 |

| Δ in Positive Emotion, γ310 | -- | -- | -- | -- | .025 | .042 |

| Waking time, β31 | −.199** | .067 | −.199** | .067 | −.200** | .067 |

Note. All momentary-level (Level 1) predictors are uncentered; Day-level (Level 2) and person-level (Level 3) predictors are grand mean centered.

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05.

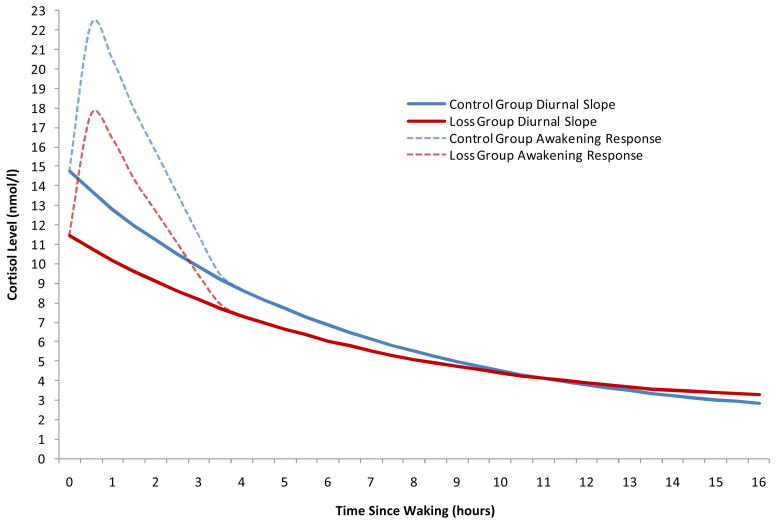

Spousal Loss and Salivary Cortisol Patterns

Table 1 provides a summary of the multilevel growth curve models. Of the health behavior covariates, only smoking status was significantly associated with wakeup levels of cortisol. Compared with nonsmokers, smokers exhibited significantly higher cortisol levels at wakeup (75% higher, γ004 = .557, p < .05; equivalent to 1.75 nmol/L). Furthermore, baseline levels of negative emotion were significantly associated with basal salivary cortisol activity, with higher levels of negative emotion predicting lower levels of cortisol at wakeup (22% lower, γ008 = −.244, p < .05; equivalent to 0.78 nmol/L). As shown in model 2, spousal loss demonstrated distinct associations with several diurnal cortisol parameters. Compared with non-bereaved controls, bereaved respondents demonstrated significantly lower average wakeup levels of salivary cortisol (21% lower, γ009 = −.233, p < .05; equivalent to .79 nmol/L). As illustrated in Figure 1, the slope of the diurnal cortisol curve was significantly flatter among bereaved spouses (γ109 = .021, p < .05; equivalent to 1.02 nmol/L). There was no main effect of spousal loss on the size of the CAR (γ309 = .063, p =.551).

Figure 1.

Average cortisol rhythms across the waking day by bereavement status.

Mediating Effect of Positive Emotion

To test the hypothesis that prospective changes in positive emotion would mediate the associations between loss and diurnal cortisol parameters, both bereavement status and pre- to post-loss changes in positive emotion at Level 3 were examined using a 2-2-1 multilevel mediation model (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). Using this model, analyses indicated that prospective changes in positive emotion did not account for the association between spousal loss and participants’ cortisol levels at wakeup, suggesting that this effect is not solely due to intra-individual changes in positive emotion. In contrast, the coefficient for the previously observed spousal loss effect on average diurnal cortisol slopes was reduced in size. Table 2 shows that the coefficient for spousal loss fell from .021 to .016. The latter coefficient is the direct effect of loss on the diurnal cortisol slope, and it is nonsignificant (γ109 = .016, p =.092). The indirect effect of spousal loss through changes in positive emotions is .007 units and reflects how much spousal loss affects changes in the diurnal cortisol slope through positive emotions. The proportion of the indirect effect to the total effect is .29, indicating that pre- to post-loss changes in positive emotion explained 29% of the effect of spousal loss on diurnal cortisol slopes (see MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

The significance of the mediation effect was evaluated following the procedure outlined by Mackinnon and colleagues (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; MacKinnon, et al., 2004).3 Specifically, asymmetric confidence limits (CL) were formed using the upper and lower critical values of the distribution of the product of two standard normal variables (Meeker, Cornwell, & Aroian, 1981). If zero was not in the 95% interval of the upper and lower confidence limits, we concluded that the mediation effect was statistically significant. Using this method, the lower and upper 95% confidence limits based on the distribution of the product were .0011 and .0138, suggesting that the mediated effect of changes in positive emotion is statistically significant.4 This effect was significant even when possible confounding factors, such as awakening time, demographic variables, extraversion, neuroticism, negative emotion, and health covariates were included in the model.

Discussion

This prospective longitudinal study identified significant differences in HPA-axis function and positive emotion among adults recently bereaved by spousal loss compared with non-bereaved controls. Although prior research has examined longitudinal relationships between spousal bereavement and cortisol levels (e.g., Pfeffer, et al., 2009), the current study is among the first to document a potential mechanism (i.e., positive emotion) by which bereavement may affect the diurnal rhythm of salivary cortisol in older adults.

Findings from the current study are consistent with the hypothesis that bereavement is associated with altered diurnal cortisol activity. As predicted, bereaved partners had significantly flatter diurnal cortisol slopes. This finding is in accordance with other research illustrating the chronic impact of bereavement on HPA-axis dysregulation (Hagan, et al., 2010; Tyrka, et al., 2008) and provides further support for flattened diurnal cortisol patterns as a marker of increased vulnerability to stress (Adam & Gunnar, 2001; Elzinga, et al., 2008; Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007; Sephton, Sapolsky, Kraemer, & Spiegel, 2000). Of note, this association was independent of potential confounding factors, including demographic variables (e.g., age, SES), personality (e.g., extraversion and neuroticism), negative emotion, and health behavior covariates (e.g., smoking status), that have been previously found to be related to flatter diurnal slopes (Adam & Kumari, 2009; Cohen, et al., 2006).

In the current investigation, spousal bereavement was associated with lower levels of cortisol at wakeup. Prior evidence for associations between basal cortisol levels and bereavement has been mixed, however, with some studies reporting higher basal cortisol levels, and others reporting no or negative associations with bereavement (Bloch, Peleg, Koren, Aner, & Klein, 2007; Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm, & Schuder, 2001; Pfeffer, Altemus, Heo, & Jiang, 2007). Future studies might address these inconsistencies by examining differences in characteristics of the loss experience (type, duration, intensity), sample composition (developmental age, history of psychiatric illness), and cortisol measurements (variability in awakening time, defining cortisol slopes with vs. without the CAR period).

Our meditational findings for the diurnal cortisol slopes highlight how positive emotions may play an important role in the pathway leading from bereavement to HPA-axis dysregulation. In particular, deficits in positive emotion following loss fully accounted for the differences in observed diurnal cortisol slopes. As noted, observational studies that have focused on the health effects of positive emotions have often failed to include adequate controls for negative mood states. Thus, it is important to note that consistent with previous research (e.g., Steptoe, et al., 2008; Steptoe, et al., 2005), the associations between positive emotion and cortisol were independent of negative emotion in the current study.

In general, these findings add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that positive emotions confer a wide range of benefits during bereavement (Bonanno & Keltner, 1997; Coifman & Bonanno, 2010; Ong, Bergeman, & Bisconti, 2004). Importantly, the findings also highlight the need for future investigations to clarify the mechanism by which an overall disturbance in positive emotion following loss is linked to later HPA vulnerability. If the failure to mobilize adequate positive emotional resources in the aftermath of loss represents a significant risk factor for the development of HPA dysregulation, then interventions (Luecken, et al., 2010) designed to bolster bereaved individuals’ capacity for emotional awareness and positive emotional engagement during times of stress may prove to be beneficial.

There are several limitations to this study. First, generalizability is limited by a sample of predominantly female Caucasians. Additionally, the data on cortisol were obtained over a 4-day period at a single point in bereavement, on average 17.5 months post-loss. Thus, it will be important for future studies to examine cortisol responses during bereavement at multiple time points, both closer and further away from the loss event. Similarly, data for the current study were based on cortisol awakening responses measured over two occasions (waking and 30 mins later). A recent meta-analytic review (Chida & Steptoe, 2008) found that the association between positive psychological traits (e.g., positive emotion) and cortisol awakening responses (CAR) was moderated by the number of cortisol assessments: positive psychological traits were associated with reduced CAR only in studies that assessed cortisol three or more times across the waking period. Future investigations should include greater number of cortisol assessments to increase measurement reliability. A final limitation of the study is the fact that we could not objectively assess the effects of participant noncompliance with the saliva sampling protocol. Whether compliance is enhanced by research that incorporates monitoring of sample timings using objective devices, such as “smart-cap” salivettes and actigraphy (Adam & Kumari, 2009; Almeida, McGonagle, et al., 2009), remains to be determined.

Despite these limitations, this is the first prospective study, to our knowledge, to examine the effect of spousal bereavement and positive emotion on naturally occurring daily cortisol levels. The pattern of observed findings is consistent with evidence from other studies suggesting that major psychosocial stressors, such as the death of a partner, can produce long-term dysregulation of the HPA axis, and deficits in positive emotion following loss may represent a key mechanism by which bereavement is linked to HPA dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We extend thanks to John Eckenrode, Gary Evans, and Karl Pillemer for their helpful comments on previous versions of this article.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01 AG020166) to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS (Midlife in the U.S.) investigation and a National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH18931). The original study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development.

Footnotes

Because bereavement studies have rarely collected data beyond 2 years postloss (for a review, see Bonanno & Kaltman, 2001), we limit our analyses to data gathered on average 18 months after the death of a spouse.

Due to the logarithmically transformed outcome variable (natural log of cortisol values), the exponential function of that transformation was applied to return the intercept to its original scale of measurement (nmol/L).

The upper and lower confidence limits for the indirect effect were calculated using PRODCLIN (distribution of the PRODuct Confidence Limits for Indirect effects). The SAS and R macro programming languages used to run PRODCLIN are described in MacKinnon et al. (2004).

To ensure that the multilevel coefficients we report are robust, we reanalyzed the data on (1) the full sample of non-bereaved individuals and (2) a random augmented sample of matched non-bereaved controls that was 3 times the bereaved group. We note that the pattern of findings remains unchanged and is virtually identical when using either the full sample (n = 994) or random augmented matched sample (n = 66) of non-bereaved controls. Given this, we opted to select a random sample that was comparable in size to the bereaved group.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea

References

- Adam EK. Transactions among adolescent trait and state emotion and diurnal and momentary cortisol activity in natural settings. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:664–679. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Gunnar MR. Relationship functioning and home and work demands predict individual differences in diurnal cortisol patterns in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:189–208. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Hawkley LC, Kudielka BM, Cacioppo JT. Day-to-day dynamics of experience-cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:17058–17063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Kumari M. Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1423–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, McGonagle KA, King H. Assessing daily stress processes in social surveys by combining stressor exposure and salivary cortisol. Biodemography and Social Biology. 2009;55:220–238. doi: 10.1080/19485560903382338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Piazza JR, Stawski RS. Interindividual differences and intraindividual variability in the cortisol awakening response: An examination of age and gender. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:819–827. doi: 10.1037/a0017910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch M, Peleg I, Koren D, Aner H, Klein E. Long-term effects of early parental loss due to divorce on the HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;51:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. The varieties of grief experience. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:705–734. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Keltner D. Facial expressions of emotion and the course of conjugal bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:126–137. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn NM. The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago: Aldine; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Steptoe A. Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Biological Psychology. 2008;80:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N, Allison P. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:719–730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Schwartz JE, Epel E, Kirschbaum C, Sidney S, Seeman T. Socioeconomic status, race, and diurnal cortisol decline in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:41–50. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195967.51768.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coifman KG, Bonanno GA. When distress does not become depression: Emotion context sensitivity and adjustment to bereavement. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:479–490. doi: 10.1037/a0020113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga BM, Roelofs K, Tollenaar MS, Bakvis P, van Pelt J, Spinhoven P. Diminished cortisol responses to psychosocial stress associated with lifetime adverse events: A study among healthy young subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio A. A concurrent validational study of the NCHS General Well-Being Schedule. 73. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the big-five factor structure. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Morison SJ, Chisholm K, Schuder M. Salivary cortisol levels in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:611–628. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100311x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan MJ, Luecken LJ, Sandler IN, Tein J. Prospective effects of post-bereavement negative events on cortisol activity in parentally bereaved youth. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:394–400. doi: 10.1002/dev.20433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruschka DJ, Kohrt BA, Worthman CM. Estimating between- and within-individual variation in cortisol levels using multilevel models. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:698–714. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs N, Myin-Germeys I, Derom C, Delespaul P, van Os J, Nicolson NA. A momentary assessment study of the relationship between affective and adrenocortical stress responses in daily life. Biological Psychology. 2007;74:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychobiological research: A overview. Neuropsychobiology. 1989;22:150–169. doi: 10.1159/000118611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH. Salivary cortisol in psychoneuroendocrine research: Recent developments and applications. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1994;19:313–333. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ. Childhood attachment and loss experiences affect adult cardiovascular and cortisol function. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1998;60:765–772. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Appelhans BM. Early parental loss and salivary cortisol in young adulthood: The moderating role of family environment. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:295–308. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Hagan MJ, Sandler IN, Tein JY, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA. Cortisol levels six-years after participating in the Family Bereavement Program. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:785–789. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker WQ, Cornwell LW, Aroian LA. Selected tables in mathematical statistics: The product of two normally distributed random variables. VII. Providence: American Mathematical Society; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Meinlschmidt G, Heim C. Decreased cortisol awakening response after early loss experience. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:568–576. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:25–45. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: A developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson NA. Childhood parental loss and cortisol levels in adult men. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1012–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. The role of daily positive emotions during conjugal bereavement. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59B:P168–P176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Bonanno GA. Prospective predictors of positive emotions following spousal loss. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:653–660. doi: 10.1037/a0018870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Altemus M, Heo M, Jiang H. Salivary cortisol and psychopathology in children bereaved by the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer CR, Altemus M, Heo M, Jiang H. Salivary cortisol and psychopathology in adults bereaved by the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2009;39:215–226. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.3.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk DE, Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Kirschbaum C. State and trait affect as predictors of salivary cortisol in healthy adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 6: Hierchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR, Ives DG. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:161–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythms as a predictor of breast cancer survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth J, Ockenfels MC, Porter L, Kirschbaum C, Hellhammer DH, Stone AA. Stressors and mood measured on a momentary basis are associated with salivary cortisol secretion. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:353–370. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger UM, Fleeson W, Baltes PB. Predictors of subjective physical health and global well-being: Similarities and differences between the United States and Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, O’Donnell K, Badrick E, Kumari M, Marmot MG. Neuroendocrine and inflammatory factors associated with positive affect in healthy men and women: Whitehall II study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;167:96–102. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Wardle J, Marmot M. Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardivascular, and inflamatory processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:6508–6512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370:1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier L, Price LH, Ross N, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, et al. Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Patrick DL, Marmon T, Simon GE, Katon WJ. Depressive symptoms and mortality in a prospective study of 2,558 older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002:521–530. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eck M, Berkhof H, Nicolson N, Sulon J. The effects of perceived stress, traits, mood states, and stressful daily events on salivary cortisol. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:447–458. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]