Abstract

Background

The present study sought to identify predictors of outcome for a comprehensive cognitive therapy (CT) developed for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Methods

Treatment was delivered over 22 sessions and included standard CT methods, as well as specific strategies designed for subtypes of OCD including religious, sexual and other obsessions. This study of 39 participants assigned to CT examined predictors of outcomes assessed on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. A variety of baseline symptom variables were examined as well as treatment expectancy and motivation.

Results

Findings indicated that participants who perceived themselves as having more severe OCD at baseline remained in treatment but more severe symptoms were marginally associated with worse outcome for those who completed therapy. Depressed and anxious mood did not predict post-test outcome, but more Axis I comorbid diagnoses (mainly major depression and anxiety disorders), predicted more improvement, as did the presence of sexual (but not religious) OCD symptoms, and stronger motivation (but not expectancy). A small rebound in OCD symptoms at 1-year follow-up was significantly predicted by higher scores on personality traits, especially for schizotypal (but not obsessive-compulsive personality) traits.

Conclusions

Longer treatment may be needed for those with more severe symptoms at the outset. CT may have positive effects not only on OCD symptoms but also on comorbid depressive and anxious disorders and associated underlying core beliefs. Findings are discussed in light of study limitations and research on other predictors.

Keywords: cognitive therapy, obsessive-compulsive disorder, treatment, comorbidity, motivation, expectancy

Various forms of cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Response rates for individuals who complete exposure and response prevention (ERP), a first-line treatment for OCD (e.g., [1]), are as high as approximately 85% (e.g., [2]). However, because ERP requires patients to engage in prolonged exposure to their feared stimuli while refraining from compulsions, the prospect of ERP is intimidating and the emotional toll of treatment can be difficult to tolerate. Drop-out and refusal rates for ERP are therefore relatively high. Notwithstanding the unambiguous evidence base for this treatment, there is a clear need for alternative therapeutic approaches.

Cognitive therapy (CT) appears to be an efficacious alternative to ERP. According to cognitive models, intrusive thoughts themselves are not pathological; rather, OCD is the result of a pattern of maladaptive beliefs about those thoughts and their meaning (e.g., [3]). Individuals with OCD tend to perceive intrusive thoughts as dangerous and significant, leading to anxiety and compensatory compulsions. Particular domains of belief that are related to OCD include importance and control of thoughts, inflated responsibility, intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism, and overestimation of threat [4]. During CT, patients learn to notice their maladaptive patterns of thinking, reevaluate their beliefs, and ultimately modify them to alleviate distress and reduce obsessions. Patients also conduct behavioral experiments to test predictions based on beliefs in order to correct their assumptions and alter their behavior accordingly. Although these experiments are a form of exposure, they are not designed to induce prolonged discomfort and promote habituation as it typical of ERP.

A number of studies provide evidence supporting the efficacy of CT for OCD (e.g., [5, 6]). Following these studies, our group developed a CT protocol for OCD to be delivered in a flexible, modular format tailored to the belief domains most relevant to individual patients' idiographic presentations [7]. In a small open trial, modular CT was associated with moderate decreases in OCD symptoms, especially among patients who had not received previous behavior therapy [8]. The results of a waitlist controlled trial revealed that individuals who received CT experienced large decreases in OCD symptoms that were largely maintained for at least 12 months [9].

A primary impetus to develop multiple efficacious treatments for a given disorder is to accommodate individual differences in treatment response and patient preference. Hence, efforts to identify predictors of treatment outcome can improve patient care by guiding treatment selection. The aim of this study is to identify potential predictors of treatment outcome using data from both the pilot study and waitlist controlled trial of modular CT for OCD [9]. Based on clinical experience and previous research on predictors of outcome for various OCD treatments, we identified several potential predictor variables as detailed below. Although guided by informed hypotheses, this investigation is exploratory.

Pre-treatment OCD severity predicted worse post-treatment outcome in several studies of various forms of CBT [2, 10-13], although not in others (cf. [14-16]). However, even if pre-treatment severity predicts post-treatment symptom severity, participants may improve at the same rate over time regardless of initial severity. Hence, one aim was to evaluate the impact of pre-treatment severity on the rate of improvement from CT over the course of treatment.

The relationship between Axis I comorbidity and treatment outcome is equivocal. The results of several investigations of depression or depressive symptoms are mixed and few studies have examined any other comorbid disorders (for a review see [17]). Several studies, however, have found that although the presence of comorbidity was associated with increased pre-treatment severity in various internalizing disorders, it did not adversely affect treatment outcome [18-20]. In light of these studies, another aim was to evaluate the impact of Axis I comorbidity on treatment outcome in CT for OCD.

Clinical experience and empirical data suggest that symptoms of personality disorders can interfere with treatment. Most clear is the relationship between traits of schizotypal personality disorder and negative outcome in OCD treatments (e.g., [21-23]), although other studies implicate other personality clusters, as well (e.g., [10, 24, 25]). We therefore examined the relationship between personality disorder traits and outcome.

A number of studies have found that sexual and religious obsessions are associated with poor outcome in CBT and pharmacotherapy ([12, 26-28]; but see [29]). Among many possible reasons, sexual and religious obsessions may be difficult to treat because they are associated with greater reluctance on the part of patients to risk moral consequences, difficulty designing in vivo exposures that confront such consequences, poor insight, and especially distorted thinking (e.g., [17, 30, 31]). Some have suggested that CT is particularly well-suited for sexual and religious obsessions (e.g., [7, 8]). In contrast, the presence of contamination and washing symptoms may predict worse response to CT [7]. We therefore investigated the relationships between treatment outcome and sexual, religious, and contamination obsessions.

Patient motivation and expectancy have also been implicated as potential moderators of outcome. Clinical experience suggests that patient motivation is a critical prerequisite for treatment success, particularly in intensive ERP (e.g., [32]). Indeed, several studies have found that motivation predicted positive treatment outcome in both CBT and pharmacotherapy for OCD (e.g., [10, 11, 33]; but see [34]), and at least two studies are in progress to investigate the utility of adding motivational enhancement techniques to improve outcome [35, 36]. In addition, some have argued that a sizable portion of variance in treatment effects can be attributed to patient expectations (e.g., [37]). However, expectancy did not predict treatment outcome in four studies of CBT for OCD [34, 38-40]. In light of these studies, we also examined patient motivation and expectancy as possible predictors.

Finally, in light of the notable relationship between OCD and disability (e.g., [41]) and previous studies showing poor functioning to be a predictor of negative outcome (e.g., [42]), we investigated whether pre-treatment disability was related to CT outcome.

Analyses of three domains were conducted to identify factors that may impact the effectiveness of CT on OCD: 1) predictors of early drop-out; 2) predictors of change in OCD symptom severity during treatment; and 3) predictors of change in OCD symptom severity at follow-up.

Method

Participants

Participants were 39 adults (age 18 or older) with a primary DSM-IV diagnosis of OCD (but not primary hoarding) and a Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale score greater than 16. Participants came from an uncontrolled pilot trial (n = 10) and a waitlist controlled trial (n = 29) that followed. Exclusion criteria were Tourette's disorder, severe cognitive dysfunction, mental retardation, dementia, brain damage, or symptoms requiring psychiatric hospitalization, including current psychotic or suicidal symptoms. In addition, participants were excluded if they were currently engaged in psychotherapy, had received CT for OCD, or 10 sessions of behavior therapy for OCD. Individuals in the waitlist but not the pilot trial were permitted to receive pharmacotherapy provided the dosage was stable for two months before and throughout the study. Two additional participants who enrolled but were later found to have been ineligible were excluded from analyses. As both samples were similar, they were combined to increase power.

The sample was 54% women, predominantly Caucasian (37 Caucasian, 1 Asian, 1 Hispanic), and with mean age of 32.6 (SD = 10.1). Thirteen were taking medications, including antidepressants (n = 12) and benzodiazepines (n = 4). Nineteen participants (49%) had at least one current comorbid axis I disorder, including major depression (n = 12), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 5), social phobia (n = 5), specific phobia (n = 5), body dysmorphic disorder (n = 2), dysthymic disorder (n = 2), binge-eating disorder (n = 2), and panic disorder (n = 1). Of the 39 participants, 2 refused treatment and 9 others dropped out during treatment, leaving 28 who attended the post-treatment evaluation and at least one follow-up visit. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the procedures were explained.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Patient Version (SCID-P)

The SCID-P [43] is a clinician-administered, semi-structured interview to assess DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders. In the controlled trial, reliability data indicated a kappa of 1.00 for OCD diagnosis based on 20% of taped assessments rated by an independent doctoral level clinician [9].

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)

The Y-BOCS [44] is a 10-question clinician-administered measure of OCD symptom severity for which a score of 16 indicates clinically meaningful OCD. The Y-BOCS is sensitive to change over the course of treatment [45]. Internal consistency for baseline scores in the current sample was α = .78. Inter-rater reliability for participants in the CT controlled trial was r = .97 for 20% of taped interviews rated independently.

Padua Inventory-Revised (PI-R)

The PI-R [46] is a 41-item self-report measure of OCD symptom severity. Some participants received a 60-item version of the measure [47], which contains all of the items in the PI-R for which scores were derived. Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .85.

Obsessive Compulsive Checklist Rating Scales

This measure [7] was derived from the Y-BOCS Symptom Checklist in order to rate the severity of specific types of obsessions and compulsions [48]. Participants rate the severity of symptoms on an 11-point scale from no problem to very severe (frequency & distress). For the purposes of this investigation, we examined patient ratings of sexual, religious, and contamination obsessions.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The BDI [49] and BAI [50] are well known, 21-item, self-report measures of the severity of depressive and anxious symptoms. Both have high internal consistency, test-retest reliability and construct validity. Internal consistency for baseline scores in the current sample was α = .89 for the BDI and α = .93 for the BAI.

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4th edition (PDQ-4)

The PDQ-4 [51] is a 99-item self-report measure of personality disorder traits. Its psychometric properties have not been well characterized, but there is some evidence that the PDQ-4 has utility as a screening measure for the potential presence of a personality disorder (e.g., [52]). Of particular interest were the total score denoting overall personality disturbance, and the schizotypal and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) subscales.

Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)

The SDS [53] is a 3-item self-report measure on which participants rate work, social and family disability on an 11-point scale. The SDS has acceptable reliability and validity [54] and has been used in OCD samples (e.g., [55]).

University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire (URICA)

The URICA [56] is a 32-item self-report questionnaire that measures motivation to change. The URICA yields four subscales: Precontemplation, Contemplation, Action, and Maintenance. To improve internal reliability of the Action subscale, questions 10 and 17 for the pilot participants, and question 20 for the waitlist control participants were excluded because they were negatively correlated with other questions in the subscale. Internal consistency for these modified scales was α = .69 for Precontemplation, α = .71 for Contemplation, α = .67 for Action, and α = .82 for Maintenance. We calculated Readiness-to-Change (RTC), an overall estimate of motivation to change (e.g., [34]), by subtracting the mean Precontemplation score from the sum of the mean scores for the other three subscales. The URICA was administered after session 4 or 6 (for pilot and waitlist control participants, respectively) to ensure that participants fully understood the goals and strategies of CT. It was examined as a predictor of Y-BOCS change from that point forward.

Expectancy Rating

Patients completed 4 questions about the credibility of the treatment rationale and their expectations of change due to treatment [57]; these were summed to create a composite expectancy score. Two versions of the expectancy measure (on 9-point and 10-point scales, respectively) were administered to different patients; scores based on 10-point scales were multiplied by 0.9 and rounded to the nearest integer. Like the URICA, the measure of expectancy was completed after session 4 or 6 to ensure that participants fully understood the therapy goals and strategies, and was examined as a predictor of Y-BOCS change from that point forward.

Treatment

Treatment consisted of 22 sessions of CT based on Beck's model [7] conducted by clinicians in training who were supervised weekly. The first 20 sessions were held weekly for one hour and the final two sessions were spaced two weeks apart. The first 4 sessions included a detailed assessment of patients' OCD symptoms, psychiatric and social history, and OCD-relevant misinterpretations. Also included was educational information about applying the cognitive model of OCD to patients' current symptoms and thought records to illustrate the model. During sessions 5 through 20 the therapist selected treatment modules relevant to each patient's particular beliefs. Over these 16 weeks, most patients covered 4 to 5 treatment modules. The final two sessions focused on relapse prevention, including reviewing CT techniques learned during treatment, identifying common triggers for OCD symptoms and strategies to help maintain gains, and planning adaptive activities to fill time formerly occupied by obsessions and rituals. Ratings of therapist adherence and competence in the waitlist controlled trial are reported elsewhere and were excellent [9].

Statistical Methods

Baseline candidate predictors examined included: Y-BOCS total and insight scores; PI-R; major depressive episode (Yes/No); BDI; BAI; Axis I comorbidity (Yes/No); PDQ-4 total; PDQ-4 schizotypal traits (categorized as 0, 1-2, 3-6) and schizotypal diagnosis (Yes/No); PDQ-4 number of OCPD symptoms and OCPD diagnosis (Yes/No); SDS Work, Social, and Family scores; OC Checklist scores for sexual, religious, and contamination obsessions (categorized by tertile due to lack of linearity); use of psychiatric medications at baseline (Yes/No). URICA (categorized by tertile due to lack of linearity) and expectancy scores were administered at session 4 or 6 and examined as predictors of change from that point forward. Composite scores were calculated if fewer than 10% of questions were unanswered, in which case missing values were set to the mean of all questions in that (sub-)scale. Drop-out (Yes/No) was defined as completing at least 18 sessions of treatment or terminating treatment earlier following marked improvement (the case for one patient). Logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of drop-out.

Predictors of change in Y-BOCS were identified through longitudinal models with random effects for the slope and intercept. Such methods make use of data at all time points and implicitly control for baseline values. Models of change in Y-BOCS during treatment included scores at baseline, week 4/6, week 8, week 12, week 16/18, and week 24; models of change in Y-BOCS during follow-up included scores at week 24 and months 3, 6, and 12. Due to limited power, univariate models were first examined to identify significant predictors at α = .05, and multivariate analyses and variable selection were then conducted at α = .10. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients and potential confounding in multivariate analyses were also examined.

Results

Table 1 summarizes baseline demographics, and Table 2 summarizes the significant predictors for all analyses. To ensure that all potentially important variables are identified for future study, variables that predicted outcome at α = .10, univariately, are also reported.

Table 1. Baseline Demographics.

| Baseline Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Axis I comorbidity | 19 (49%) |

| Current major depressive episode | 12 (31%) |

| PDQ-4 Schizotypal Diagnosis | 3 (8%) |

| PDQ-4 OCPD Diagnosis | 18 (46%) |

| Current use of psychiatric medications | 13 (33%) |

| mean (SD) | |

| Y-BOCS Total | 25.54 (4.30) |

| Y-BOCS Insight | 0.81 (1.01) |

| Padua Total | 57.77 (22.82) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 13.23 (8.67) |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 13.91 (11.25) |

| PDQ-4 Total | 27.53 (12.24) |

| Sheehan Disability Scale – Work | 4.25 (2.78) |

| Sheehan Disability Scale - Social/Leisure | 4.44 (2.43) |

| Sheehan Disability Scale - Family/Home | 4.29 (2.46) |

Note. PDQ-4 = Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4th edition; OCPD = obsessive-compulsive personality disorder; Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale.

Table 2. Predictors of Drop-Out and Y-BOCS Change during CT Treatment and in Follow-Up.

| Outcome | Univariate Predictor | Estimate | Standard Error | DF | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drop-out (Yes vs. No) | PI-R Total Score | -0.042 | 0.0208 | 1 | 0.046 |

| Y-BOCS Change (Tx) | Time * Sexual Obsessions | - | - | 2, 91 | 0.0071 |

| ≥4 vs. 0 | -0.31 | 0.107 | 0.0043 | ||

| 1-3 vs. 0 | 0.12 | 0.160 | 0.47 | ||

| Time * Comorbidity (Yes vs. No) | -0.22 | 0.0996 | 1, 95 | 0.032 | |

| Time * SDS Work Score | 0.032 | 0.0185 | 1, 92 | 0.083 | |

| Y-BOCS Change (Tx) (week 4/6 onward) |

Time * URICA RTC Score | - | - | 2, 55 | 0.043 |

| 10.4–11.3 vs. ≥11.4 | 0.25 | 0.130 | 0.057 | ||

| ≤10.3 vs. ≥11.4 | 0.31 | 0.129 | 0.021 | ||

| Y-BOCS Change (FU) | Time * PDQ-4 Total Score | 0.0043 | 0.00150 | 1, 42 | 0.0064 |

| Time * PDQ-4 Schizotypal | - | - | 1, 42 | 0.011 | |

| 3+ vs. 0 | 0.096 | 0.0343 | 0.0074 | ||

| 1-2 vs. 0 | 0.094 | 0.0376 | 0.017 |

Note. PI-R = Padua Inventory – Revised; Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; URICA RTC = University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire Readiness-to-Change; PDQ-4 = Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4th edition; Tx = post-treatment; FU = follow-up.

Drop-Out

Eleven patients (28%) dropped out early, completing an average of 8 sessions (range = 0 – 17), including 2 participants who refused to begin treatment altogether. As seen in Table 2, the only significant predictor of drop-out was the PI-R. A 10-point lower baseline PI-R score resulted in a 52% greater likelihood of dropping out early (OR [95% CI] = 1.52 [1.0 – 2.3]). Thus, patients who perceived their symptoms to be more severe were more likely to complete treatment.

Post-Treatment

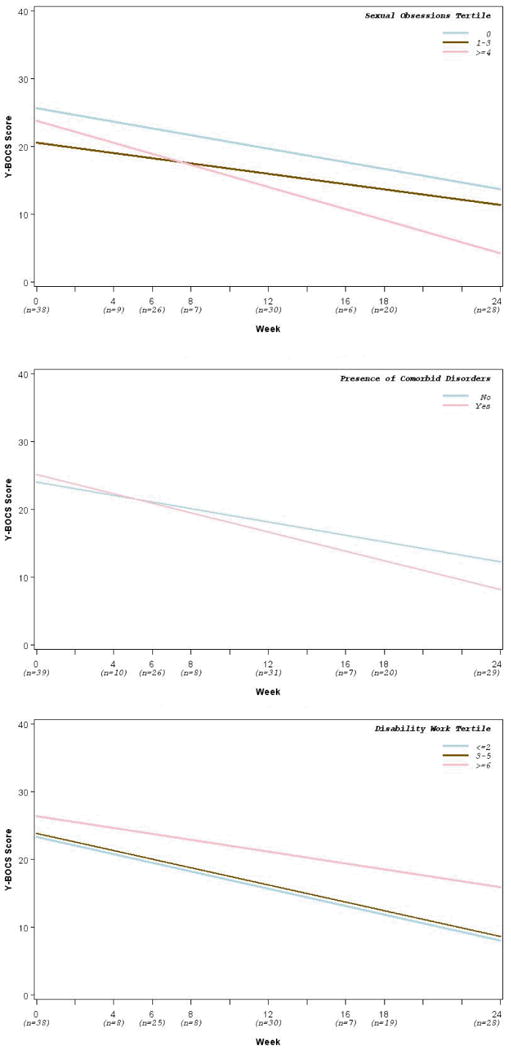

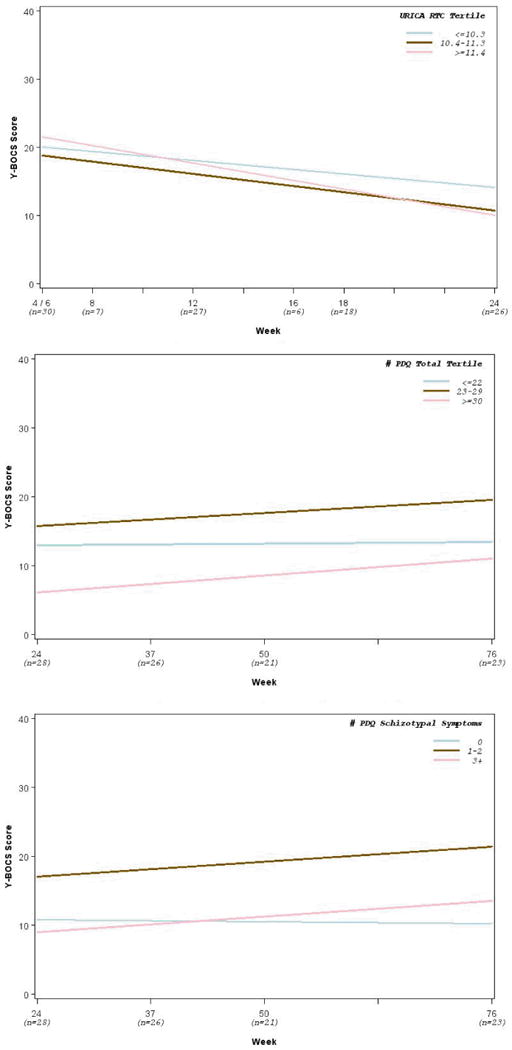

Over the course of treatment, total Y-BOCS scores decreased by 14 points on average (p < .0001). Baseline Y-BOCS score was a borderline significant predictor of change following treatment, with higher baseline severity resulting in less improvement over time (correlation between random effects: r = .49, p = .057). Significant predictors included the presence of sexual obsessions and Axis I comorbidity, both predicting greater improvement. As evident in Figure 1, patients with a score of 4 or more on sexual obsessions had a 7.5 point greater decrease in Y-BOCS (95% CI = [2.4 – 12.6]) over treatment compared to patients without such obsessions. Patients with 1 or more comorbid disorders had a 5.2 point greater decrease in Y-BOCS (95% CI = [0.5 – 10.0]) over treatment compared to patients with no comorbidity. Although there was little correlation between the two significant predictors (ρ = .039), confounding was observed in a multivariate model, and so Table 2 reports the effects from univariate models. Neither BDI nor BAI baseline scores predicted outcomes at post-treatment (ps > .32). SDS Work was a marginally significant predictor; a 3-point higher baseline Work score resulted in a 2.3-point smaller decrease in Y-BOCS score over treatment, on average. Neither religious (p = .78) nor contamination obsessions (p = .30) were significant predictors of improvement, nor were the SDS Social (p = .49) and Family (p = .58) scores.

Figure 1. Mean Baseline and Change in Y-BOCS by Levels of Predictors.

In analyses examining predictors of Y-BOCS change from week 4/6 onward, motivation significantly predicted improvement as indexed by the composite RTC score. Patients in the highest tertile of the RTC score had a 7.4 point greater decrease (95% CI = [1.2 – 13.6]) in Y-BOCS over the course of treatment compared to patients in the lowest tertile, and a 6.1 point greater decrease compared to patients in the middle tertile. There was no difference between patients in the lower two tertiles. Expectancy did not predict Y-BOCS change (p = .68).

Follow-Up

During the 1-year follow-up, total Y-BOCS score increased by an average of 2.6 points (p = .0084). This rebound was significantly predicted by PDQ-4 total and schizotypal scores. A 10-point higher baseline PDQ-4 total score resulted in a 2.2 point increase (95% CI = [0.7 – 3.8]) in Y-BOCS after treatment cessation. Compared to patients with 0 baseline schizotypal symptoms, those with 1-2 or 3+ symptoms experienced about a 5-point greater increase in Y-BOCS over the 1 year of follow-up after treatment completion. There was no significant difference in the increase in Y-BOCS during follow-up for patients with 1-2 and with 3+ schizotypal symptoms.

Discussion

The present study aimed to identify predictors of drop-out, post-treatment outcome, and follow-up outcome for patients treated with CT for OCD. In the present sample, more severe OCD symptoms on the PI-R predicted lower rates of drop-out. Interestingly, the Y-BOCS did not significantly predict drop-out. This may suggest that only self-perceived, but not clinician-rated, severity has a bearing on motivation and investment in treatment, although it is possible that this finding occurred by chance.

Consistent with previous studies, lower baseline Y-BOCS scores were marginally associated with better outcome. More severe participants appeared to benefit from treatment at a slower rate than did those who were less severe at baseline. Perhaps modifying more severe OCD symptoms with cognitive strategies requires more time, or severe patients find it more difficult to engage in treatment. Patients with severe OCD may benefit from longer or more intensive treatment protocols, whereas those with milder cases may respond more quickly to standard courses of therapy. Flexibility in therapy duration may be an important key for successful outcomes (see also [39]).

In this sample, continuous measures of depressed and anxious mood did not predict outcome. In contrast, comorbid Axis I disorders significantly predicted greater improvement in Y-BOCS scores during treatment. This finding contradicts clinical lore, although the empirical literature on comorbidity is more equivocal (e.g., [17-20]). One possibility is that comorbidity indicates higher overall levels of distress and impairment which may translate to greater motivation. Another possibility is that cognitive strategies also worked for comorbid conditions, especially the commonly co-occurring major depression and anxiety disorders, leading to more relief of overall distress. A third possibility is that participants with comorbid disorders had more negative core beliefs that were also responsive to the CT methods. This finding merits attention in larger trials that can examine how both primary and secondary diagnoses respond to treatment.

Although the presence of sexual obsessions has predicted worse outcomes for patients with OCD, more severe sexual obsessions predicted greater improvement in this sample. This finding is consistent with our clinical impression that CT provides a promising approach to sexual obsessions. In CT, patients are taught to evaluate sexual obsessions more objectively, disconnect their obsessions from negative core beliefs, and eventually let the thoughts come and go naturally. Ratings of religious obsessions, however, did not predict treatment outcome. Religious obsessions may differ from sexual ones in that they do not easily lend themselves to gathering disconfirming evidence, and the therapist may not be considered an authority over the religious implications of certain thoughts. In contrast, the patient may be better able to learn that intrusive, sexual thoughts are common and meaningless.

In the current study, work disability marginally predicted less improvement during active treatment. Perhaps work disability provoked increased distress that interfered with treatment, although why this might be true for work but not social or family disability is unclear. Alternatively, work disability may have interfered with motivation if financial benefits might be lost.

Measures of motivation collected during the first 4 to 6 weeks of therapy significantly predicted improvement, consistent with some studies (e.g., [10, 11, 33]; but see [34]). However, the relationship between motivation and outcome was not linear. Participants with the highest levels of motivation improved much more than did those with moderate or low motivation. This finding suggests that patients below a certain threshold of motivation would benefit from motivational strategies before starting active treatment. Studies of motivational aspects of OCD treatment are ongoing [35, 36].

Treatment gains from CT for OCD were not contingent upon expectations of improvement. This is consistent with several OCD trials in which expectancy did not predict outcome [34, 38-40]. It is worthy of note, however, that treatment expectancy assessed as late as the 6th week of therapy is likely influenced by early symptom improvement. For this reason we examined Y-BOCS change only from that point forward, but it remains possible that pre-treatment expectancy predicts during-treatment improvement.

A small but significant rebound in symptoms in the year after therapy was significantly predicted by higher baseline scores on personality disorder traits, especially for schizotypal, but not OCPD, traits. This finding mirrors literature showing an adverse effect of personality disorders (e.g., [58]), specifically schizotypal or Cluster A disorders (e.g., [10, 23, 24]), on CBT for OCD, but mainly for immediate rather than longer-term outcomes (see [25, 59]). In fact, relatively few studies have examined predictors of follow-up outcomes where personality factors that are not improved during therapy may exert their strongest effect.

The implications of this investigation are limited by the exploratory nature of several analyses, as well as the small sample size. Attention to potential predictors significant at α = .10 has the potential to increase the likelihood of Type I error. Thus, the results detailed here await replication and are intended to be heuristic for future research. Furthermore, lack of significance in this analysis may not preclude an association, since the analyses were underpowered. Finally, 11 participants (28%) did not begin or withdrew early from treatment. Considering that the relatively high drop-out and refusal rate for ERP is one impetus for developing alternative treatments, this finding merits further attention.

OCD is often severe and debilitating. Although effective treatments exist, there is still much room for improving outcomes and tailoring treatments to increase the number of patients who benefit. CT for OCD is a promising approach that may be used instead of, or as an adjunct to, traditional exposure-based therapies. In the present study, predictors of outcome were generally consistent with extant literature with some interesting exceptions, including comorbidity and the presence of sexual obsessions. Replication of the current findings may offer some promise in guiding the development of optimal, tailored, and likely flexible treatments for individuals who suffer from OCD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kimberly Wilson, Bethany Teachman, Ulrike Buhlmann, and Elana Golan for their help with this project.

Drs. Wilhelm, Steketee, Chosak, and Fama have received research support from NIMH for this study (NIMH grant MH58804, PI: Wilhelm). Drs. Wilhelm and Steketee received royalties from their CT treatment manual published by New Harbinger Publications.

In addition, we have the following disclosures, which are not directly relevant for this project. Drs. Wilhelm, Fama, Chosak, and Siev, and Ms. Keshaviah have received private donor funding from the David Judah Fund. Drs. Wilhelm and Fama have received research support from the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation. Dr. Wilhelm has also received research support from the FDA and the Tourette Syndrome Association. Forest Laboratories provided her with medication for an NIMH funded study. Drs. Wilhelm, Fama, and Chosak are presenters for the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy in educational programs supported through independent medical education grants from pharmaceutical companies. Drs. Wilhelm and Fama have also received speaking honoraria from various academic institutions. Drs. Wilhelm and Steketee have also received royalties from Guilford Publications and Oxford University Press.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Obsessive-compulsive disorder (National Clinical Practice Guideline 31) London, UK: The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2007, from www.nice.org.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin ME, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, et al. Effectiveness of exposure and ritual prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Randomized compared with nonrandomized samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rachman S. A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group OCCW Cognitive assessment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:667–681. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottraux J, Note I, Yao SN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy versus intensive behavior therapy in obsessive compulsive disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:288–297. doi: 10.1159/000056269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whittal ML, Thordarson DS, McLean PD. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: Cognitive behavior therapy vs. exposure and response prevention. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1559–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilhelm S, Steketee GS. Cognitive therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: A guide for professionals. Oakland, CA US: New Harbinger Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm S, Steketee G, Reilly-Harrington NA, et al. Effectiveness of Cognitive Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Open Trial. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;19:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilhelm S, Steketee G, Fama JM, et al. Modular Cognitive Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Wait-List Controlled Trial. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:294–305. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Haan E, van Oppen P, van Balkom AJLM, et al. Prediction of outcome and early vs. late improvement in OCD patients treated with cognitive behaviour therapy and pharmacotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keijsers GPJ, Hoogduin CAL, Schaap CPDR. Predictors of treatment outcome in the behavioural treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:781–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM, Greist JH, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions as predictors of compliance with and response to behaviour therapy: Results from a controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:255–262. doi: 10.1159/000064812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLean PD, Whittal ML, Thordarson DS, et al. Cognitive versus behavior therapy in the group treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foa EB, Grayson JB, Steketee GS, et al. Success and failure in the behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:287–297. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogduin CA, Duivenvoorden HJ. A decision model in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive neuroses. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:516–521. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rufer M, Fricke S, Moritz S, et al. Symptom dimensions in obsessive- compulsive disorder: Prediction of cognitive-behavior therapy outcome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keeley ML, Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Geffken GR. Clinical predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:118–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis L, Barlow DH, Smith L. Comorbidity and the Treatment of Principal Anxiety Disorders in a Naturalistic Sample. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storch EA, Lewin AB, Farrell L, et al. Does cognitive-behavioral therapy response among adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder differ as a function of certain comorbidities? J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman MG, Przeworski A, Fisher AJ, Borkovec TD. Diagnostic comorbidity in adults with generalized anxiety disorder: Impact of comorbidity on psychotherapy outcome and impact of psychotherapy on comorbid diagnoses. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fricke S, Moritz S, Andresen B, et al. Do personality disorders predict negative treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorders? A prospective 6-month follow-up study. European Psychiatry. 2006;21:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moritz S, Fricke S, Jacobsen D, et al. Positive schizotypal symptoms predict treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minichiello WE, Baer L, Jenike MA. Schizotypal Personality Disorder: A poor prognostic indicator for behavior therapy in the treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1987;1:273–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen B, Vogel PA, Stiles TC, Götestam KG. Influence of co-morbid generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and personality disorders on the outcome of cognitive behavioural treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2007;36:145–155. doi: 10.1080/16506070701259374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steketee G, Chambless DL, Tran GQ. Effects of axis I and II comorbidity on behavior therapy outcome for obsessive-compulsive disorder and agoraphobia. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:76–86. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrão YA, Shavitt RG, Bedin NR, et al. Clinical features associated to refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2006;94:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso P, Menchon JM, Pifarre J, et al. Long-term follow-up and predictors of clinical outcome in obsessive-compulsive patients treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:535–540. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n07a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rufer M, Grothusen A, Maß R, et al. Temporal stability of symptom dimensions in adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Schwartz SA, Furr JM. Symptom Presentation and Outcome of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1049–1057. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huppert JD, Siev J. Treating scrupulosity in religious individuals using cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolin DF, Abramowitz JS, Kozak MJ, Foa EB. Fixity of belief, perceptual aberration, and magical ideation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2001;15:501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foa EB, Franklin ME. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. 3rd. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 209–263. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinto A, Pinto AM, Neziroglu F, Yaryura-Tobias JA. Motivation to change as a predictor of treatment response in obsessive compulsive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19:83–87. doi: 10.1080/10401230701334747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel PA, Hansen B, Stiles TC, Götestam KG. Treatment motivation, treatment expectancy, and helping alliance as predictors of outcome in cognitive behavioral treatment of OCD. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2006;37:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCabe RE, Rowa K, Antony MM, et al. In: Using motivational interviewing to augment treatment outcome with exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder: Preliminary findings. Westra HA, editor. Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Orlando, FL: 2008. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simpson HB, Zuckoff A. Using motivational interviewing to enhance treatment outcome in people with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.009. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg RP, Constantino MJ, Bruce N. Are patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:657–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Başoğlu M, Lax T, Kasvikis Y, Marks IM. Predictors of improvement in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1988;2:299–317. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freeston MH, Ladouceur R, Gagnon F, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive thoughts: A controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:405–413. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lax T, Başoğlu M, Marks IM. Expectancy and compliance as predictors of outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1992;20:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mancebo MC, Greenberg B, Grant JE, et al. Correlates of occupational disability in a clinical sample of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steketee G. Social support and treatment outcome of obsessive compulsive disorder at 9-month follow-up. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1993;21:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- 43.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Version. 2nd. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Landau P, Katz R. Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder with clomipramine. Psychiatric Annals. 1989;19:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Oppen P, Hoekstra RJ, Emmelkamp PMG. The structure of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0010-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanavio E. Obsessions and compulsions: The Padua Inventory. Behav Res Ther. 1988;26:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(88)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilhelm S, Baer L. Obsessive Compulsive Checklist Rating Scales (Clinical version, Patient version) Boston: Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Depression Inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hyler SE. Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ-4+) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okada M, Oltmanns TF. Comparison of three self-report measures of personality pathology. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31:358–367. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9130-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York: Scribner's; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: The Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:39–45. doi: 10.1002/da.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenstein DK, Franklin ME, McGuffin P. Measuring motivation to change: An examination of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire (URICA) in an adolescent sample. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1999;36:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kempe PT, van Oppen P, de Haan E, et al. Predictors of course in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Logistic regression versus Cox regression for recurrent events. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:201–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dreessen L, Hoekstra R, Arntz A. Personality disorders do not influence the results of cognitive and behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11:503–521. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]