Abstract

A review of empirical literature reveals improvements in service utilization and outcomes for women when substance abuse and child welfare services are integrated. The increased use of substances by women involved in the child welfare system has resulted in a call for integrated, coordinated, evidence-based practices. Since the late 1990s, specific system- and service-level strategies have been developed to coordinate and integrate the provision of substance abuse and child welfare services such that women are remaining in treatment longer and are more likely to reduce substance use and be reunited with their children. The strategies reviewed provide useful guidelines for developing components of effective, evidence-based programs for substance-involved women in the child welfare system.

Keywords: integrated services, substance abuse, child welfare, wome

Estimates of the percentage of parents involved in the child welfare system with serious substance abuse problems range as high as 50–80% and have resulted in a variety of service models and service system modifications to address the problem of parental substance abuse in child welfare. More than 10 years ago, Young, Gardner, and Dennis (1998) outlined the challenges associated with identifying and meeting the service needs of substance abusing parents in the child welfare system. Aspects of the challenges those authors identified remain, but a growing body of evidence now demonstrates that improvements in child welfare service utilization and outcomes result when substance abuse and child welfare services are integrated within the same service setting. Child welfare service systems have identified strategies at both the systems level and the service delivery levels to integrate services, including collaborative working relationships with substance abuse treatment and child welfare administrators and service providers, child welfare worker training to better identify substance abuse problems, processes to facilitate parents’ entry and engagement in substance abuse treatment, and working relationships with family courts (Lee, Esaki, & Green, 2009; McAlpine, Marshall, & Doran, 2001; Lee, Esaki, & Green, 2009; Osterling & Austin, 2008; Ryan, Choi, Hong, Hernandez, & Larrison, 2008; Semidei, Radel, & Nolan, 2001; Worcel, Furrer, Green, Burrus, & Finigan, 2008). The purpose of this paper is to review the service system and service delivery context as well progress that has been made in the development of integrated services for substance abusing parents involved in the child welfare system.

Background and Context

The public substance abuse and child welfare service systems were each developed under distinct legislative, administrative, and financing structures. The public substance abuse service system was developed in the 1970s to address a growing concern with drug “epidemics” and to respond to the service needs of stigmatized, drug-using populations. Women substance users were of special concern in consideration of the potential deleterious effect of their substance abuse on their children (Marsh, Colten, & Tucker, 1982; Colten & Marsh, 1983; Marsh & Miller, 1985). The public substance abuse service system was largely built on existing private, non-profit agencies and expanded when states receive federal funds through categorical block grants. The public child welfare system, in comparison, developed in response to a series of legislative mandates concerned with safety, permanency, and well-being of children. The public system also was built on an existing private system and expanded in the 1950s and 1960s when financing became available to states through Title IVE of the Social Security Act.

The existence of distinct service systems has created barriers to the provision of evidence-based practices to substance-abusing parents in the child welfare system. Only in the 1990s, as the extent of substance involvement by parents in the child welfare system was documented, did policy analysts, practitioners, and researchers begin to call for and develop integrated service strategies (Young et al., 1998). At the same time, analysts and researchers began to assess the system and service level barriers to effective treatment for this service group (Feig, 1998). At least four aspects of child welfare and substance abuse service systems and service strategies created difficulties in developing programs incorporating evidence-based knowledge about recovery from substance abuse disorders in child welfare settings: (1) regulatory environments and administrative structures in two systems, (2) treatment philosophies and time frames, (3) assessment strategies, and (4) standards of success and failure.

Regulatory environment and administrative structures

Despite the fact that substance abuse and child welfare systems often serve the same clients, distinct goals and philosophies and work force requirements have led to separate administrative structures within state-level human service organizations. Although variation occurs across states, substance abuse and child welfare agencies invariably involve distinctive state-level leadership, licensing and quality assurance mechanisms, and separate management information systems that do not cross-communicate.

Treatment goals and philosophies

Perhaps the greatest distinction between substance abuse and child welfare systems results from their treatment goals and philosophies. The philosophy surrounding substance abuse treatment has been heavily influenced by recovery movements which emphasize the idea of abstinence through supportive, self-policing peers and paraprofessionals (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous) (Burnam & Watkins, 2006). While substance abuse treatment models are increasingly evidence-based and the workforce increasingly professionalized, the influence of the recovery movement can be found in treatment goals that are abstinence-oriented and reinforced by a paraprofessional workforce.

The rehabilitation orientation of the substance abuse service system contrasts distinctly with the regulation orientation of the child welfare system. Further, in the child welfare system, parents of children found to be abused or neglected are regulated by the child welfare system, and the children are the primary recipients of treatment resources. The history and structure of the child welfare system reflect an emphasis on protecting children by separating them from their families rather than supporting families to preserve the family unit. Child welfare services are largely driven by legislation designed to protect children rather than to treat or rehabilitate parents.

The most recent legislation affecting child welfare services is the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) of 1997. ASFA was passed, in part, to address the perceived impact of parental substance abuse in the child welfare system. In the 1990s, child welfare administrators, caseworkers, and commentators argued that child welfare policies were allowing parents too many chances and too much time to meet reunification requirements and, as a result, children were lingering in foster care and being denied permanency (Bartholet, 1999; Gelles, 1997). Based on child developmental research pointing to the importance of stability and predictability in children’s lives (Goldstein, Solnit, Goldstein, & Freud, 1996), ASFA instituted shorter deadlines for establishing return home versus adoption permanency goals. ASFA developed specific timelines to insure that children achieved permanent and stable living situations and established a foster care time limit after which states could initiate efforts to terminate biological parental rights. The AFSA service philosophy clearly prioritized child permanency over parental rehabilitation and family preservation.

Assessment strategies

Both the substance abuse and child welfare service systems have applied relatively narrow processes of problem assessment. Although it is well-documented that clients of both service systems have multiple co-occurring problems (Brady & Ashley, 2005; Clark, 2001; Dore & Doris, 1998; Grella, Hser, & Huang, 2006; Hser & Niv, 2006), substance abuse programs have often limited the focus of assessment at treatment entry to substance abuse problems, while child welfare programs have traditionally focused primarily on parenting. Until recently, for example, standard family assessment tools used by child welfare workers included only general observations rather than specific questions about substance abuse (Dore, Doris, & Wright, 1995).

The evidence is overwhelming, however, that clients served in both substance abuse and child welfare service systems have multiple problems. A recent study of parents with substance abuse problems involved with the child welfare system indicated only 8% had only a substance abuse problem; 30% had at least one other problem (i.e., mental health, domestic violence, housing); 35% had two other problems; and 27% had three (Marsh, Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006). Similarly, a study of pregnant or parenting women who received residential substance abuse treatment indicated that 49% had mental health problems, 77% were victims of abuse, 50% had criminal justice involvement, and 60% had physical health problems (Porowski, Burgdorf, & Herrell, 2004). Another study of parents involved with child protective services and the courts indicated that 59% of these parents had mental health problems as well (Stromwall et al., 2008). Despite the overwhelming evidence that substance-involved families in the child welfare system are dealing with multiple problems, assessment strategies focus narrowly on either substance abuse or child welfare issues. As a result, both service systems are ill-equipped to identify the broad range of client problems or to provide comprehensive services designed to address them.

Standards of success and failure

Both substance abuse and child welfare service systems also have applied relatively narrow standards of service impact. Through the influence of the recovery movement, substance abuse has focused on abstinence from substance use as an absolute measure of success. However, as neuroscience reveals addiction to be a chronic brain disease characterized by relapse, outcome measures in the substance abuse field have broadened to include relapse prevention, controlled substance use, and improved social functioning (McLellan, 2002; McLellan, McKay, Forman, Cacciola, & Kemp, 2005; Tatarsky, 2003). In child welfare, “satisfactory” progress toward service plan goals is the standard measure of success and failure. When parents have substance abuse problems, satisfactory progress is typically indicated by abstinence (demonstrated through random-interval urine screens) as well as completion of substance abuse treatment according to deadlines consistent with regulatory requirements of ASFA, but inconsistent with research supporting addiction as a chronic brain disease. ASFA regulatory time frames also conflict with evidence linking longer treatment stays to greater chances of attaining lasting positive outcomes (Connors, Grant, Crone, & Whiteside-Mansell, 2006; National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2009). Thus, parents with substance abuse problems who become involved with the child welfare system face deadlines and expectations about the nature of addiction as well as outcome measures that are inconsistent with the research evidence.

Consequences of a Fragmented Service Context

Increasingly, research has documented the damage to children and families when child welfare and substance abuse service systems lack coordination and integration. For example, children from substance-abusing families are more likely to be placed in out-of-home care than in-home or community care (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 1999). Parents can face delays and other obstacles to treatment entry that negatively affect child welfare assessments (Gregoire & Schultz, 2001; McAlpine, Courts-Marshall, & Harper-Doran, 2001; Young, Gardner, & Dennis 1998). Further, the faster reunifications and case closures experienced by substance-involved families following ASFA may be less stable than slower ones (Rockhill, Green, & Furrer, 2007; Wulczyn, Harden, & George, 1997; Wulczyn, 2004). A study that specifically examined re-entry to foster care rates for cases involving parental substance abuse found that cases moving quickly to reunification and disallowing sufficient time for ongoing services and monitoring had especially high re-entry rates (Terling, 1999). Another study indicated that substance-using parents in the child welfare system are skeptical about the effectiveness of a fragmented service system and, as a result, may be hesitant to accept services. A longitudinal qualitative study addressing parents’ perspectives on the challenges they face in overcoming addiction and attaining favorable child welfare decisions found that the parents were reluctant to enter treatment because they had concluded that available substance abuse treatment options did not offer sufficient hope for recovery from addiction or reunification of their children from foster care (Rockhill, Green, & Newton-Curtis, 2008).

In addition to contributing to ineffective services and poor child welfare outcomes, the lack of coordination and integration of the substance abuse and child welfare systems has meant that clients are not receiving treatments of proven effectiveness. Lundgren, Schilling, and Peloquin (2005) reported that despite evidence about which treatment approaches work best for different types of substance abusers, such knowledge is infrequently used in child welfare service planning. New brain research highlights the importance of treatment approaches that address the full complexity of addiction. Such approaches involve a continuum of care in which parents engage in different treatment modalities as they progress through a recovery process. Such approaches also can incorporate pharmacological therapies or medications in addition to behavioral therapy. Medications such as buprenorphrine for opiate addiction and naltrexone for opiate or alcohol addiction, for example, have been demonstrated to be potentially effective treatment approaches (NIDA, 2007). Yet, parents involved with child welfare services rarely receive them. Choi and Ryan (2006), for example, found that only 24% of heroin users in a child welfare sample had been referred for methadone treatment, despite evidence of methadone’s effectiveness in treating heroin addiction. In sum, the rapid growth in knowledge of evidence-based substance abuse treatment for women has had too little impact on the delivery of child welfare services.

Mothers in Substance Abuse Treatment

Women enter substance abuse treatment with more serious dependencies (Boyd & Mieczkowski, 1990; Kosten, Gawin, Kosten, & Rounsaville, 1993; Halinkas, Crosby, Pearson, & Nugent, 1994; Wechsberg, Craddock, & Hubbard, 1998; Morgenstern & Bux, 2003) and with more health and social problems than do men (Marsh & Miller, 1985; Wechsberg, Craddock, & Hubbard, 1998; Chatham, Hiller, Rowan-Szal, Joe, & Simpson, 1999; Marsh, Cao, & D’Aunno, 2004). Although women and men remain in treatment for comparable periods of time, women are more likely than men to use services available in comprehensive programs (McLellan & McKay, 1998; Grella, Joshi, & Hser, 2000; Ashley, Marsden, & Brady, 2003; Marsh & Cao, 2005) and more likely to benefit from them (Greenfield et al., 2007). Women also report that relationship with their service provider is an important service element enabling them to remain in treatment (Nelson-Zlupko, Dore, Kauffman, & Kaltenbach, 1996). Substance-involved women commonly describe parenting concerns and fears of losing their children to the child welfare system (Magura & Laudet, 1996; Tracy, 1994). In a study of parents of children under 18 in California, 20% of mothers were afraid of losing custody of their children and 32% of mothers reported they were in treatment to regain custody of their children. Although the motivation for the development of services integrated with the child welfare system derived originally from concerns with the well-being of children, a commitment to the development of special services for women also has contributed to efforts to develop effective, evidence-based practices (Marsh, D’Aunno, & Smith, 2000; Marsh, Cao, & D’Aunno, 2004; Olmstead & Sindelar, 2004).

Integrated Services at the System Level

Service integration strategies that have been recommended at the system level include flexible financing, educational strategies, and increased administrative accountability (Burnam & Watkins, 2006; Schroder, Lemieux, & Pogue, 2008; Young, Gardner, & Dennis, 1998). Flexible financing is required to overcome the funding “silos” that characterize human service systems at the state level. Some states have developed inter-agency agreements to jointly fund programs targeted at substance-abusing parents involved in the child welfare system. Some state substance abuse agencies prioritize services for pregnant women or parents in the child welfare system to increase access. And, in Illinois and several other states, the Title IVE Waiver mechanism was used to capture Title IVE funds to support an integrated services research and demonstration program (Ryan, Marsh, Testa, & Louderman, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, 2005; Graham, 2007). In the Illinois example, parents with children in foster care were linked with a substance abuse recovery coach. An evaluation using a randomized control design found that parents with a recovery coach were somewhat more likely than parents receiving typical services to achieve reunification and to avoid a new substance-exposed birth (Ryan et al., 2006; Ryan et al., 2008).

Other significant system-level service integration strategies involve the institution of Family Treatment Drug Courts and service co-location. Modeled on criminal drug courts, Family Treatment Drug Courts serve substance-abusing families in the child welfare system and involve integration of child welfare and substance abuse services via court mandates. Evaluations of Family Treatment Drug Courts have associated them with greater treatment enrollment, faster treatment enrollment, and increased chances of family reunification (Green, Furrer, Worcel, Burrus, & Finigan, 2007; Worcel Furrer, Green, Burris, & Finigan, 2008; Boles, Young, Moore, & DiPirro-Beard, 2007). Another significant system-level service integration involves the placement – or collocation – of substance abuse treatment counselors in child welfare offices. Whereas collocation initiatives are still early in an evaluation process, initial evaluation findings suggest that the approach can lead to increased understanding among child welfare and substance abuse staff, improved relationships among service providers, and better coordination of services for clients (Lee, Esaki, & Green, 2009; McAlpine, Courts-Marshall, & Harper-Doran, 2001). In addition to specific initiatives, broad education and training mechanisms also have been used with major stakeholders such as judges, practitioners, and policymakers to increase knowledge of the value of integrated services. Finally, separate management information systems remain a challenge for many states to assess the need for integrated services and the performance of public systems in providing them.

Integrated Services at Service Level: Comprehensive Services

Although effective service integration takes place at both system and service levels, service-level strategies designed to link clients with comprehensive services are relevant to the development of effective programs. The substantial services research literature connecting the provision of comprehensive services and service linkage to specific substance abuse and child welfare outcomes provides the basis for articulating specific components of a service integration model designed to overcome many of the barriers to service integration discussed above.

Co-occurring service needs are common among women seeking substance abuse treatment, but co-occurring needs are especially characteristic of women with substance abuse problems involved with the child welfare system (Grella, Hser, & Huang, 2006). Compelling evidence points to the potential of comprehensive services to improve child welfare outcomes for mothers involved with the child welfare system (Mullins, Bard, & Ondersma, 2005; Osterling & Austin, 2008; Marsh Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006). Comprehensive services also have been shown to lead to better substance abuse treatment outcomes (McLellan, Arndt, Metzger, Woody, & O’Brien, 1993; McLellan et al., 1998), especially for women (Marsh, Cao, & D’Aunno, 2004; Grella, Needell, Shi, & Hser, 2009). Research examining the relation between comprehensive services and positive child welfare outcomes includes an Illinois study indicating reunification rates were highest for parents who had addressed other pressing mental health, housing, and domestic violence problems (Marsh, Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006). A California study found that mothers who attended treatment programs providing more comprehensive services to address multiple service needs were more likely to achieve reunification than were mothers who attended programs offering fewer ancillary support services (Grella, Needell, Shi, & Hser, 2009).

Whereas such findings are encouraging, and most published studies of comprehensive service programs find positive child welfare outcomes, caution is nonetheless warranted, and more research is needed. One recent evaluation of a comprehensive substance abuse services program for parents with children in foster care found that program participants took longer to reunify and were more likely to reenter foster care than were comparison families who received standard services (Brook & McDonald, 2007).

A Comprehensive Service Model

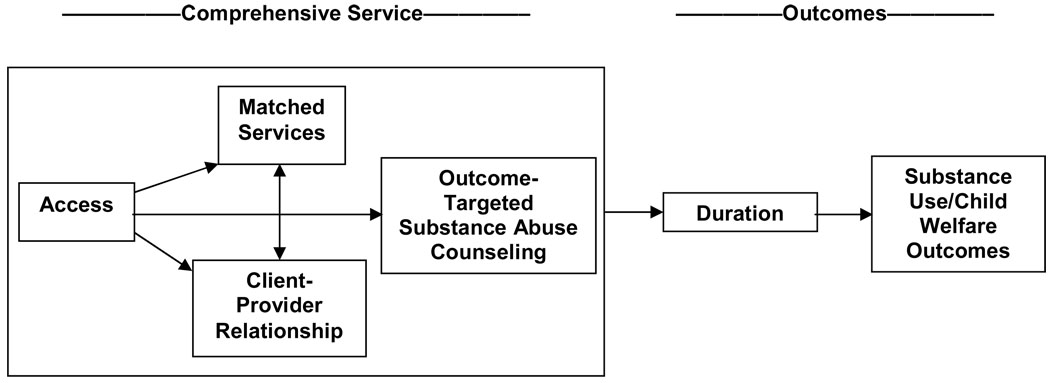

Potentially important services and service mechanisms have been identified in the analysis of comprehensive substance abuse treatment approaches where ancillary health and social services are provided along with substance abuse counseling and child welfare services (McLellan et al., 1998; Friedmann, Alexander, Jin, & D’Aunno, 1999; Friedmann, Hendrickson, Gerstein, & Zhang, 2004; Marsh, Cao, Guerrero, & Shin, 2009; Marsh, Shin, & Cao, in press; Marsh, Cao, & Shin, 2009). This empirical research provides the basis for developing a comprehensive service model with four key ingredients or service mechanisms and two types of outcome. The structure of these services and service mechanisms in relation to service outcome is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Components of Comprehensive Service Model

Service mechanisms

The service mechanisms include (1) access services designed to increase linkage to substance abuse services, (2) outcome-targeted services or substance abuse counseling, (3) matched services, i.e., services received by clients that match their descriptions of need, and (4) client-provider relationship.

Access services represent any service that increases the likelihood that a client will be able to reach or obtain the services they need. Lack of access to substance abuse treatment has been a greater problem for women than men, and recent research has shown that specific linkage or access services designed to reduce specific barriers that limit access for women – such as lack of child care or transportation – enable them to remain in treatment and reduce post-treatment drug use (Marsh, D’Aunno, & Smith, 2000; Marsh, Cao, & Shin, 2009; Olmstead & Sindelar, 2004; Smith, Marsh, & D’Aunno, 1998). Access services can include a variety of service types (D’Aunno, 1997). Recent research in child welfare has shown that transportation, child care, and intensive case management are access services that can enable clients to receive services and ultimately to reduce substance use and increase reunification rates (Marsh, et al., 2000; Marsh, Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006).

Outcome-targeted services are those directly focused on the outcome of interest. In substance abuse treatment, substance abuse counseling is a service specifically designed to reduce substance use. Treatment effectiveness research provides consistent evidence of the impact of substance abuse counseling on reduced substance use (Egertson, Fox, & Leshner, 1997). In child welfare, a primary treatment tool is parent training designed to increase the capacity of the parent to provide a safe and stable environment for the child. While there are numerous evaluations of parent training programs, there have been limited studies of the specific impact of parent training in the child welfare system on child welfare outcomes of safety, permanency and well-being (Barth, Gibbons, & Guo, 2005; Berry, 1988). Researchers and practitioners should explore further the potentially fruitful approach of promoting stronger parent-child bonds and bolstering parents’ confidence as a step toward also addressing substance abuse problems. Traditionally in child welfare settings, substance abuse treatment is viewed as a means to safer parenting. Perhaps better parenting can be a means to substance abuse recovery (Barth, 2009; Testa & Smith, 2009).

Evidence also is accumulating that when services are matched to specific client-identified needs, comprehensive services are most effectively delivered as part of substance abuse treatment (Friedmann, Hendrickson, Gerstein, & Zhang, 2004; Smith & Marsh, 2002; McLellan et al., 1997; Marsh et al., 2009; Marsh, Cao, & Shin, 2009). Providing services to clients with multiple problems requires the capacity to ask the client to define their problems or service needs and then to respond with the needed services. As noted above, a fundamental barrier to service integration has been the failure conduct a comprehensive assessment, to obtain the client’s perspective.

The client-provider relationship also has been found to be an important element in substance abuse treatment. A set of recently reviewed studies indicates that client-provider relationship is a reasonably consistent predictor of retention in treatment, but an inconsistent predictor of post-treatment substance use (Dakof et al., 2003; Meier, Barrowclough, & Donmall, 2005). Overall, evidence indicates each of these factors – access services, substance abuse services, matched services, and client-provider relationship – can serve as a mediator or a mechanism through which positive substance abuse outcomes are achieved.

Intermediate and ultimate outcomes

In the evaluation of social services, it is beneficial to examine both intermediate and ultimate outcomes. Intermediate outcomes are the more immediate effects of treatment, such as treatment completion or time spent in treatment, while ultimate outcomes are measures of client functioning in the long term. Since a necessary condition to achieving ultimate outcomes is to remain in treatment long enough to benefit from service elements, time spent in treatment, i.e., treatment duration or retention, is a common intermediate outcome in both child welfare and substance abuse services research. Child welfare research has shown a correlation between remaining in treatment or treatment completion and child welfare outcome of family reunification (Green, Rockhill, & Furrer, 2007; Grella, Needell, Shi, & Hser, 2009; Marsh, Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006). And, substance abuse services research has shown treatment duration is a robust predictor of positive substance abuse treatment outcomes (Price, 1997; Simpson, 1979; Simpson, Joe, & Brown, 1997; Zhang, Friedmann, & Gerstein, 2003). An analysis of three large substance abuse treatment studies found that about half (46%–59%) of women who did not complete treatment or stayed for less than three months were abstinent one year after discharge, compared to 76% of those who either completed treatment or stayed for more than six months (Greenfield et al., 2004). Zhang et al. (2003) found a linear relation between duration and drug use improvement for typical treatment stays in methadone maintenance, outpatient, and long-term residential modalities.

Ultimate outcomes in both substance abuse and child welfare measure longer-term effects of services related to client functioning. In child welfare, effects of services on client functioning have been measured in terms reunification of the child with the family or whether the child has achieved some other form of permanency (through adoption or subsidized guardianship) as well as whether he or she is on a positive developmental trajectory. In substance abuse, ultimate outcomes are increasingly measured in terms of reductions in drug use as well mental, physical, and social functioning.

This comprehensive service model promotes service integration and addresses barriers preventing integration in several ways. First, by incorporating access or linkage services as a distinct service component, the model recognizes the difficulties that women, more than men, have had in connecting with services. It acknowledges that access services such as transportation, child care, and intensive case management – specifically designed to facilitate linkage to services – are especially beneficial for women. Unless a service model incorporates a component to actively facilitate access to services, clients will be less likely to receive them and to benefit. Service intensity, dosage (or the amount of service that a client receives) has been evaluated in a variety of ways in services research, including counts of the number of different services a client receives, counts of any service contact regardless of type of service, or measures of length of services or service duration. The comprehensive service model described here promotes service integration by sorting services received into outcome-targeted services and matched services. By specifying outcome-targeted services, the provider is required to be clear that services are in place that are specifically designed to impact the outcome of interest. While substance abuse counseling, including the use of medications, has a well-documented relation to reductions in substance use, child welfare interventions which have consisted primarily of parent training have had a less well-documented impact on child welfare outcomes of reunification and enhanced child well-being. In general child welfare interventions are less specified and less targeted on specific outcomes. Nonetheless, by specifying the inclusion of outcome-targeted services in the model, service providers are encouraged to design services that optimize achievements of the outcomes of interest – whether those outcomes are child welfare or substance use. Similarly, the inclusion of matched services acknowledges that clients have co-occurring problems and that in order to address those problems it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the broad range of client service needs (ideally from the perspective of the client) and then specifically to match services to the client-identified problem. Thus, the matched service component of the model is a measure not only of service intensity but of service targeting and appropriateness. The matched service component promotes service integration by acknowledging that clients benefit from services provided across service systems and that child welfare outcomes improve when clients’ health, mental health, housing, and educational needs are met. Finally, by including client-provider relationship, the model recognizes the relationship between provider and client is a key element of service delivery and that most interventions are conveyed in the context of a relationship. The character and quality of this relationship affect outcomes as much or more than the receipt of specific services. Overall, the comprehensive service model promotes integration at the service delivery level by promoting a comprehensive assessment that documents all the co-occurring health and social problems and systematically matches service needs to problems in the context of a positive client-provider relationship.

Summary and Implications

A review of empirical literature reveals improvements in service utilization and outcomes when substance abuse and child welfare services are integrated. Since the late1990s, specific system- and service-level strategies have been developed to coordinate and integrate the provision of substance abuse and child welfare services such that women are remaining in treatment longer and are more likely to reduce substance use and be reunified with their children. The strategies reviewed provide useful guidelines moving forward for developing components of effective, evidence-based programs for substance-involved women in the child welfare system.

The need for continued commitment to the provision of effective and appropriate services for women remains. Despite the evidence that comprehensive health and social services increase chances for more favorable substance abuse, health, mental health, and child welfare outcomes, studies have found that comprehensive services for women have diminishing availability, and parents in the child welfare system are left with unmet service needs (Campbell & Alexander, 2006; DuCharme, Mello, Roman, Knudsen, & Johnson, 2007; Grella & Greenwell, 2004; Smith & Marsh, 2002). Further, despite the gains reported in studies reviewed here, women continue to experience reduced access compared to men (Wechsberg, Luseno, & Ellerson, 2008) and to reunify with their children at very low rates nationally (Brook & McDonald, 2007; Marsh, Ryan, Choi, & Testa, 2006).

Child welfare systems have made substantial progress in identifying and responding to parental substance abuse problems. More work is needed to assure that parents receive treatment of demonstrated effectiveness. Some child welfare systems will need to shift from an emphasis on compliance with standard service packages and treatment approaches toward evidence-based strategies incorporating pharmacological therapies, levels of care, and comprehensive health and social services responding to a range of service and concrete needs. Child welfare researchers, policy makers, and practitioners must continue to support and evaluate these shifts as well as to direct public attention to the larger social and economic conditions that adversely affect so many families involved with child welfare services.

Acknowledgments

This research was completed with support from a grant to the first author from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA018741-03).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jeanne C. Marsh, University of Chicago

Brenda D. Smith, University of Alabama

References

- Ashley OS, Marsden ME, Brady TM. Effectiveness of substance abuse treatment programming for women: A review. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):19–53. doi: 10.1081/ada-120018838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP. Preventing child abuse and neglect with parent training: Evidence and opportunities. The Future of Children. 2009;19(2):95–118. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Gibbons C, Guo S. Substance abuse treatment and the recurrence of maltreatment among caregivers with children living at home: A propensity score analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;30:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholet E. Nobody’s children: Abuse and neglect, foster drift, and the adoption alternative. Boston: Beacon Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. A review of parent training programs in child welfare. Social Service Review. 1988;62(2):302–323. [Google Scholar]

- Boles SM, Young NK, Moore T, DiPirro-Beard S. The Sacramento drug dependency court: Development and outcomes. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:161–171. doi: 10.1177/1077559507300643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, Mieczkowski T. Drug use, health, family and social support in “crack” cocaine users. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15(5):481–485. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90035-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady TM, Ashley OS, editors. Women in substance abuse treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2005. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3968, Analytic Series A-26) [Google Scholar]

- Brook J, McDonald TP. Evaluating the effects of comprehensive substance abuse intervention on successful reunification. Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:664–673. [Google Scholar]

- Burnam A, Watkins KE. Substance abuse with mental disorders: Specialized public system and integrated care. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):648–658. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CI, Alexander JA. Availability of services for women in outpatient substance abuse treatment: 1995–2000. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2006;33(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11414-005-9002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatham LR, Hiller ML, Rowan-Szal GA, Joe GW, Simpson DD. Gender differences in admission and follow-up in a sample of methadone maintenance clients. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999;34(8):1137–1165. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Ryan JP. Completing substance abuse treatment in child welfare: The role of co-occurring conditions and drug of choice. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:313–325. doi: 10.1177/1077559506292607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HW. Residential substance abuse treatment for pregnant and postpartum women and their children: Treatment and policy implications. Child Welfare. 2001;80:179–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colten ME, Marsh JC. A sex roles perspective on drug and alcohol use by women. In: Widom CS, editor. Sex roles and psychopathology. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 219–248. [Google Scholar]

- Connors NA, Grant A, Crone CC, Whiteside-Mansell L. Substance abuse treatment for mothers: Treatment outcomes and the impact of length of stay. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakof DA, Quille TJ, Tejeda MJ, Alberga LR, Bandstra E, Szapocznik J. Enrolling and retaining mothers of substance-exposed infants in drug abuse treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:764–772. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aunno TA. Linking substance-abuse treatment and primary health care. In: Egertson JA, Fox DM, Leshner AI, editors. Treating drug abusers effectively. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 1997. pp. 311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Dore MM, Doris JM. Preventing child placement in substance-abusing families: A child welfare challenge. Child Welfare. 1998;77:407–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore MM, Doris JM, Wright P. Identifying substance abuse in maltreating families: A child welfare challenge. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:531–543. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuCharme LJ, Mello HL, Roman PM, Knudsen HK, Johnson JA. Service delivery in substance abuse treatment: Reexamining “comprehensive” care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34(2):121–136. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egertson JA, Fox DM, Leshner AI. Treating drug abusers effectively. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Feig L. Understanding the problem: The gap between substance abuse programs and child welfare services. In: Hampton RL, Senatore V, Gullotta TP, editors. Substance abuse, family violence, and child welfare: Bridging perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 62–95. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Alexander JA, Jin L, D’Aunno TA. On-site primary care and mental health services in outpatient drug abuse treatment units. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 1999;26(1):80–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02287796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann PD, Hendrickson JC, Gerstein DR, Zhang Z. Designated case managers as facilitators of medical and psychosocial service delivery in addition treatment programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2004;31(1):86–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02287341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ. The book of David: How preserving families can cost children’s lives. New York: Basic Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J, Solnit AJ, Goldstein S, Freud A. The best interests of the child: The least detrimental alternative. New York: The Free Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Graham E. Overview of the state substance abuse child welfare waiver demonstrations. Presentation at the National Conference on Substance Abuse, Child Welfare, and the Courts; January 31, 2007; Anaheim, CA. 2007. PowerPoint presentation. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Furrer CJ, Worcel SD, Burrus SWM, Finigan MW. How effective are family drug treatment courts? Results from a four-site national study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:43–59. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Rockhill A, Furrer C. Does substance abuse treatment make a difference for child welfare case outcomes? A statewide longitudinal analysis. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:460–473. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Rockhill A, Furrer C. Understanding patterns of substance abuse treatment for women involved with child welfare: The influence of the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:149–176. doi: 10.1080/00952990500479282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86(5):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield L, Burgdorf K, Chen X, Porowski A, Roberts T, Herrell J. Effectiveness of long-term substance abuse treatment for women: Findings from three national studies. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:537–550. doi: 10.1081/ada-200032290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire KA, Schultz DJ. Substance-abusing child welfare parents: Treatment and child placement outcomes. Child Welfare. 2001;80:433–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Greenwell L. Substance abuse treatment for women: Changes in the settings where women received treatment and types of services provided, 1987–1998. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2004;31:367–383. doi: 10.1007/BF02287690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Hser Y, Huang Y. Mothers in substance abuse treatment: Differences in characteristics based on involvement with child welfare services. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:55–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser Y. Program variation in treatment outcomes among women in residential drug treatment. Evaluation Review. 2000;24(4):364–383. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0002400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Needell B, Shi Y, Hser Y. Do drug treatment services predict reunification outcomes for mothers and their children in child welfare? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:278–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halinkas JA, Crosby RD, Pearson VL, Nugent SM. Psychiatric co-morbidity in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. American Journal of Addictions. 1994;3(1):25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y, Niv N. Pregnant women in women-only and mixed-gender substance abuse treatment programs: A comparison of client characteristics and program services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2006;33(4):431–442. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Gawin FH, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Gender differences in cocaine use and treatment response. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10:63–66. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90100-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Esaki N, Green R. Collocation: Integrating child welfare and substance abuse services. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2009;9:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren LM, Schilling RF, Peloquin SD. Evidence-based drug treatment practice and the child welfare system: The example of methadone. Social Work. 2005;50:53–63. doi: 10.1093/sw/50.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Laudet A. Parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: Review and implications for intervention. Children and Youth Services Review. 1996;18:193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D. Parents in substance abuse treatment: Implications for child welfare practice. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005;27(12):1259–1278. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D, D’Aunno TD. Gender differences in the impact of comprehensive services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(4):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D, Guerrero E, Shin HC. Need-service matching in substance abuse treatment: Racial/ethnic differences. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2009;32(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Cao D, Shin HC. Closing the need-service gap: Gender differences in matching services to client needs in comprehensive substance abuse treatment. Social Work Research. 2009;33(3):183–192. doi: 10.1093/swr/33.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Colten M, Tucker B. Women’s use of drugs and alcohol: New perspectives. Journal of Social Issues. 1982;38:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, D’Aunno TD, Smith BD. Increasing access and providing social services to improve drug abuse treatment for women with children. Addiction. 2000;95(8):1237–1247. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.958123710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Miller NA. Female clients in substance abuse treatment. International Journal of the Addictions. 1985;20:995–1019. doi: 10.3109/10826088509047762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J, Ryan J, Choi S, Testa M. Integrated services for families with multiple problems: Obstacles to family reunification. Children and Youth Services Review. 2006;28(9):1074–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JC, Shin HC, Cao D. Gender differences in client-provider relationship as an active ingredient in substance abuse treatment. Evaluation and Program Planning. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.07.016. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine C, Courts-Marshall C, Harper-Doran N. Combining child welfare and substance abuse services: A blended model of intervention. Child Welfare. 2001;80(2):129–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT. Editorial: Have we evaluated addiction treatment correctly? Implications from a chronic care perspective. Addiction. 2002;97:249–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. Journal of the American Medical Society. 1993;269(15):1953–1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Grissom GR, Zanis D, Randall M, Brill P, O’Brien CP. Problem-service “matching” in addiction treatment: A prospective study in 4 programs. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(8):730–735. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830200062008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, Gould F, Meyers K, Bencivengo M, et al. Supplemental social services improve outcomes in public addiction treatment. Addiction. 1998;93(10):1498–1499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931014895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR. The treatment of addiction: What can research offer practice? In: Lamb S, Greenlick MR, McCarty D, editors. Bridging the gap between practice and research: Forging partnerships with community-based drug and alcohol treatment. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1998. pp. 147–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, McKay JR, Forman R, Cacciola J, Kemp J. Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: From retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction. 2005;100(4):447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier PS, Barrowclough C, Donmall MC. The role of therapeutic alliance in the treatment of substance misuse: A critical review of the literature. Addiction. 2005;100:304–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Bux DA. Examining the effects of sex and ethnicity on substance abuse treatment and mediational pathways. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(8):1330–1332. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080344.96334.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins SM, Bard DE, Ondersma SJ. Comprehensive services for mothers of drug-exposed infants: Relations between program participation and subsequent child protective services reports. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:72–81. doi: 10.1177/1077559504272101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide. 2nd Ed. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2009. (NIH Publication No. 09-4180) [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. (NIH Publication No. 07-5605) [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Zlupko L, Dore M, Kauffman E, Kaltenbach K. Women in recovery: Their perception of treatment effectiveness. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1996;13:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead T, Sindelar J. To what extent are key services offered in treatment programs for special populations? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterling KL, Austin MJ. Substance abuse interventions for parents involved in the child welfare system: Evidence and implications. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2008;5:157–189. doi: 10.1300/J394v05n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porowski AW, Burgdorf K, Herrell JM. Effectiveness and sustainability of residential substance abuse treatment programs for pregnant and parenting women. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2004;27:191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Price R. What we know and what we actually do: Best practices and their prevalence in substance abuse treatment. In: Egertson JA, Fox DM, Leshner AI, editors. Treating drug users effectively. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 1997. pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill A, Green BL, Furrer C. Is the Adoption and Safe Families Act influencing child welfare outcomes for families with substance abuse issues? Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:7–19. doi: 10.1177/1077559506296139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill A, Green BL, Newton-Curtis L. Assessing substance abuse treatment: Issues for parents involved with child welfare services. Child Welfare. 2008;87:63–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Choi S, Hong SJ, Hernandez P, Larrison CR. Recovery coaches and substance exposed births: An experiment in child welfare. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:1072–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JP, Marsh JC, Testa MF, Louderman R. Integrating substance abuse treatment and child welfare services: Findings from the Illinois Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse Waiver Demonstration. Social Work Research. 2006;30:95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder J, Lemieux C, Pogue R. The collision of the Adoption and Safe Families Act and substance abuse: Research-based education and training priorities for child welfare professionals. Journal of Teaching in Social Work. 2008;28:227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Semidei J, Radel LF, Nolan C. Substance abuse and child welfare: Clear linkages and promising responses. Child Welfare. 2001;80:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD. The relation of time spent in drug abuse treatment to post-treatment outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;136(11):1449–1453. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.11.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Brown BS. Treatment retention and follow-up outcomes in the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study (DATOS) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11(4):294–307. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Marsh JC. Client-service matching in substance abuse treatment for women with children. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Marsh JC, D’Aunno T. Child welfare and substance use: Findings from a collaborative services initiative in Illinois. The Source. 1998;8(2):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Stromwall LK, Larson NC, Nieri T, Holley LC, Topping D, Castillo J, et al. Parents with co-occurring mental health and substance abuse conditions involved in child protection services: Clinical profile and treatment needs. Child Welfare. 2008;87(3):95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Blending perspectives and building common ground: A report to Congress on substance abuse and child protection. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tatarsky A. Harm reduction psychotherapy: Extending the reach of traditional substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;25:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terling T. The efficacy of family reunification practices: Reentry rates and correlates of reentry for abused and neglected children reunited with their families. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23(12):1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa MF, Smith B. Prevention and drug treatment. The Future of Children. 2009;19(2):147–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy EM. Maternal substance abuse: Protecting the child, preserving the family. Social Work. 1994;39:534–540. doi: 10.1093/sw/39.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Synthesis of findings: Title IV-E flexible funding child welfare waiver demonstrations. 2005

- Young NK, Gardner SL, Dennis K. Responding to alcohol and other drug problems in child welfare: Weaving together policy and practice. Washington, D.C.: CWLA Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Craddock SG, Hubbard RL. How are women who enter substance abuse treatment different than men? A gender comparison from the Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study. Drugs and Society. 1998;13(1/2):97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Luseno W, Ellerson RM. Reaching women substance abusers in diverse settings: Stigma and access to treatment 30 years later. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:1277–1279. doi: 10.1080/10826080802215171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worcel SD, Furrer CJ, Green BL, Burrus SWM, Finigan MW. Effects of family treatment drug courts on substance abuse and child welfare outcomes. Child Abuse Review. 2008;17(6):427–443. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn FH, Harden AW, Goerge RM. Foster care dynamics 1983–1994: An update from the Multistate Foster Care Data Archive. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn FH. Family reunification. The Future of Children. 2004;14(1):95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Friedmann PD, Gerstein DR. Does retention matter? Treatment duration and improvement in drug use. Addiction. 2003;98(5):673–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]