Abstract

Background

Decision support to facilitate informed consent is increasingly important for complicated medical tests. Here, we test a theoretical model of factors influencing decisional conflict in a study examining the effects of a decision support aid that was assigned to assist patients at high risk for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer deciding whether to pursue the microsatellite instability test.

Methods

Participants were 239 colorectal cancer patients at high familial risk for a genetic mutation who completed surveys before and after exposure to the intervention. Half of the sample was assigned to the CD-ROM aid and half received a brief description of the test. Structural equation modeling was employed to examine associations among the intervention, knowledge, pros and cons to having MSI testing, self- efficacy, preparedness and decisional conflict.

Results

The Goodness of Fit for the model was acceptable [FIML Chi-Square (df=280) =392.24;p=0.00]. As expected, the paths to decisional conflict were significant for post-intervention pros of MSI testing (t=−2.43; p<0.05), cons of MSI testing (t=2.78; p<0.05), and preparedness (t=−7.27; p<0.01). The intervention impacted decisional conflict by increasing knowledge about the MSI test and knowledge exerted its effects on decisional conflict by increasing preparedness to make a decision about the test and by increases in perceived benefits of having the test.

Conclusion

Increasing knowledge, preparedness, and perceived benefits of undergoing the MSI test facilitate informed decision making for this test.

Impact

Understanding mechanisms underlying health decisions is critical for improving decisional support.

Individuals with Lynch syndrome have an elevated lifetime risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Risk of Lynch syndrome may be assessed with a tumor-based screening test [microsatellite instability (MSI) testing or immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining]. Individuals with positive MSI or IHC results have a high likelihood of a germline genetic mutation consistent with Lynch syndrome. The Bethesda criteria distinguish important elements of personal, family, and clinical history to guide providers considering offering Lynch screening (1).

Informed consent is routinely obtained prior to DNA-based cancer predisposition genetic testing. Informed consent should educate patients about the risks, benefits, and alternatives of tests and prepare them to make the decision about testing (2–4). Provision of sufficient information is important prior to MSI testing. First, MSI testing may indicate the need for further genetic counseling and germline mutation analysis. Second, the outcome of Lynch testing may have implications for family members. Finally, genetic risk information can be difficult to understand and thus adequate preparation about family risk for cancers associated with Lynch syndrome is necessary. Unfortunately, research suggests that CRC patients have little knowledge of the MSI test (5).

Decision support aids (DAs) have been shown to facilitate decision making in a variety of clinical contexts including cancer-related genetic testing (6–8). Decisional conflict is a key construct from the Ottawa Decision Support Framework (9), and reducing decisional conflict is a primary goal for DAs (10). Most DAs target decisional conflict reduction by addressing contributors to uncertainty including providing information about benefits and risks for options. Nonetheless, little is known about the mechanisms whereby DAs affect decisional conflict. A greater understanding of mechanisms may have implications for development of more effective DAs.

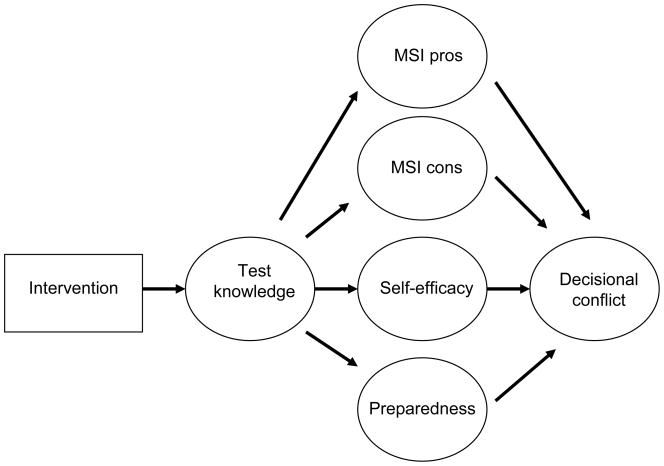

The current study tests a theoretical model (Figure 1) of factors contributing to decisional conflict about having the MSI test. The most consistent effects of DAs are upon improved knowledge about test purpose and test outcomes (6,7,11,12).Therefore, we proposed that the primary influence of the DA would be on knowledge about the MSI and IHC tests. We propose four mediating influences on the association between knowledge and conflict: perceived benefits of MSI testing, perceived barriers to MSI testing, preparedness for making the decision, and self-efficacy. Greater knowledge is predicted to lower decisional conflict by helping patients feel more informed about the test’s benefits and barriers/risks (13,14). In line with previous literature, improved knowledge would increase satisfaction with the level of decision making preparation (15). A possible mediating influence of preparedness on the association between knowledge and conflict has not previously been evaluated. A final mediator is self-efficacy defined as the level of confidence in one’s ability to understand the procedure and outcomes. DAs have been shown to increase self-efficacy (16). However, whether self-efficacy is a mechanism for the effects of improved knowledge on reduced decisional conflict has not been studied.

Figure 1.

Proposed Model of Associations between Knowledge, Attitudes, and Decisional Conflict

In the following analysis, we employed structural equation modeling to examine a mediational model of associations among knowledge, attitudes, and decisional conflict using baseline and follow-up data collected from a randomized trial of a CD-ROM intervention designed to facilitate informed consent for MSI testing (5,14).

Methods

Overview of the Randomized Study

Details of the methods are reported previously (14). Briefly, participants were 239 individuals with CRC meeting the Revised Bethesda criteria (1) who were offered MSI testing. Participants were excluded if they met more stringent “Amsterdam criteria” (17). Informed consent was signed and the participant completed the baseline survey. Participants were then assigned to either Education (E) only or E + CD-ROM. For E participants, the health educator provided a brief, standardized description of the MSI and IHC tests. For E + CD-ROM participants education was followed by viewing the CD-ROM. Participants were permitted to review the CD-ROM at their own pace. Median usage time was 24 minutes (range 10–106 minutes). Two weeks later, the follow-up assessment was completed. Of the 319 patients approached, 239 consented, completed the baseline survey (75%) and 208 (75%) completed the follow-up survey. Approximately 90% of participants were white, 44% were college educated, and 69% were married.

Measures of MSI knowledge (17-item face valid true-false measure) and IHC knowledge (8-item face valid true-false measure) were developed by the investigative team. A 14-item Benefits of MSI testing measure and a 10–item Cons of MSI testing measure were adapted from a BRCA1/2 measure (18). A 4-item Self-Efficacy scale was modeled after O’Connor’s work (19). Satisfaction with Preparation was measured with the 9-item Satisfaction with the Decision-making Process Questionnaire (20). A 10 item Completeness of Preparation scale was developed to examine how prepared participants felt to make the decision whether to have the MSI test. Decisional Conflict was assessed using the 16-item Decisional Conflict Scale (21).

Overview of the Analytic Strategy

Initially, all variables were assessed for normality. All were normally distributed with no outliers. A latent variable structural equation model (SEM) was used to test the theoretical framework (Figure 1). Prior to conducting the SEM, individual items representing each latent construct were randomly combined into item parcels reflecting that particular construct. Two item parcels for each construct were developed. The five theoretically relevant subscales for decisional conflict were used as its manifest indicators.

The analyses employed LISREL v.8.8. Because of the small amount of missing data (8.85%), Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) parameter estimation was used. In the missing data case, Goodness of Fit Indicators (GFIs) include Chi-Square and the point estimate of the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). RMSEA is used in a GFI significance test. Good fit is indicated by a non-significant Chi-Square and a non-significant RMSEA which should be less than .08 (22).

Results

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics and alphas for model variables.

Table I.

Descriptive Statistics and Factor Loadings for Variables Used in Structural Equation Analysis

| Descriptive Statistics | Factor Loadings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| M | SD | alpha | M | SD | alpha | |||

| MSI Knowledge | ||||||||

| Indicator 1 | 1.35 | 1.67 | .75 | 4.17 | 2.94 | .85 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indicator 2 | 1.64 | 2.18 | .81 | 4.07 | 2.25 | .75 | .85 | .86 |

| IHC Knowledge | ||||||||

| Indicator 1 | 1.24 | 1.06 | .47 | 1.00 | ||||

| Indicator 2 | 1.06 | 1.01 | .55 | .68 | ||||

| MSI Pros | ||||||||

| Indicator 1 | 21.89 | 3.56 | .74 | 23.03 | 4.07 | .81 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indicator 2 | 23.32 | 4.09 | .85 | 21.30 | 3.78 | .73 | .77 | .95 |

| MSI Cons | ||||||||

| Indicator 1 | 7.97 | 2.72 | .74 | 8.72 | 2.94 | .71 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indicator 2 | 9.24 | 2.85 | .68 | 9.24 | 3.18 | .80 | .77 | .79 |

| Self-Efficacy | ||||||||

| Indicator 1 | 3.94 | 1.69 | .68 | 5.42 | 1.68 | .71 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indicator 2 | 3.89 | 1.81 | .77 | 5.57 | 1.89 | .84 | .89 | .91 |

| Preparedness | ||||||||

| Completeness | 30.91 | 6.06 | .90 | 1.00 | ||||

| Satisfaction | 30.24 | 7.47 | .95 | .86 | ||||

| Decisional Conflict | ||||||||

| Uncertain | 5.57 | 2.22 | .83 | 1.00 | ||||

| Uninformed | 5.60 | 1.96 | .81 | .87 | ||||

| Unsupported | 5.28 | 1.84 | .72 | .91 | ||||

| Quality | 6.91 | 2.39 | .91 | .87 | ||||

| Unclear | 5.97 | 2.34 | .90 | .88 | ||||

Given the centrality of post-intervention knowledge in the theoretical framework (Figure 1), we examined knowledge variables predicted by treatment arm and baseline MSI and IHC knowledge. The GFIs indicated a good fit to the data [Chi-Square (df = 20) = 28.20; p = 0.10, RMSEA = 0.041 (90% C.I. 0.0, 0.074); p = 0.63)]. As reported previously (29), treatment arm was a significant predictor of post-intervention MSI and IHC knowledge (t = 2.29; p < 0.05; t = 3.03; p < 0.05, respectively). However, contrary to expectations, post-IHC knowledge was not predicted by its baseline counterpart. Removal of this path continued to yield a good fit (baseline IHC was deleted from subsequent model assessments).

Since the GFIs indicated a reasonably good fit to the data, Modification Indices (MIs) were examined to determine if conceptually supported model changes could be identified. The MIs suggested that pre-intervention MSI knowledge should predict post-intervention IHC knowledge. Freeing this path continued to yield a good fit [Chi-Square (df = 9) = 10.92; p = 0.28, RMSEA = 0.030 (90% C.I. 0.0, 0.082); p = 0.68]. The path was positive and significant (t = 3.06; p < 0.05).

Next, we examined intervening variables hypothesized to be predictors of decisional conflict. The introduction of pre- and post-intervention MSI pros yielded a well fitting model [Chi-Square (df = 37) = 33.26; p = 0.64, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% C.I. 0.0, 0.039); p = 0.99]. However, post-intervention IHC knowledge did not predict post-intervention MSI pros. Constraining this path to zero continued to yield a good model. The path from post-intervention MSI knowledge was positive and significant (t = 2.43; p < 0.05).

MSI cons were examined next. The model continued to fit well [Chi-Square (df = 77) = 86.23; p = 0.22, RMSEA = 0.02 (90% C.I. 0.0, 0.044); p = 0.99]. However, neither post-intervention MSI nor post-intervention IHC knowledge predicted post-intervention MSI cons. Nonetheless, the model GFIs remained acceptable.

The addition of pre- and post-decisional self-efficacy demonstrated that post-intervention MSI knowledge did not predict post-intervention decisional self-efficacy. However, model fit was still quite acceptable [Chi-Square (df = 139) = 157.00; p = 0.14, RMSEA = 0.023 (90% C.I. 0.0, 0.040); p = 1.00]. Constraining this path to zero still yielded an acceptable fit. The relationship between post-IHC knowledge and post-intervention self-efficacy was positive (t = 5.84; p < 0.01].

The introduction of preparedness into the model indicated that the path linking post-intervention IHC knowledge to preparedness was non-significant. Its removal led to an acceptable [Chi-Square (df= 174) = 219.21; p = 0.011, RMSEA = 0.033 (90% C.I. 0.017, 0.046; p = 0.99] fit.

Although the model in Figure 1 represents the hypothesis that the path from treatment arm to preparedness is only indirect (i.e. working through the knowledge constructs), the MIs suggested a direct path as well. Freeing the direct path demonstrated that it was significant (t = 2.74; p < 0.05). Greater preparedness was reported by those in the E + CD condition compared to those in the E condition. Model fit was still acceptable [Chi-Square (df=173) = 212.24; p = 0.023, RMSEA = 0.031 (90% C.I. 0.012, 0.044); p = 0.99].

A test of the full model depicted in Figure 2 showed that model GFI was quite acceptable [Chi-Square (df= 280) = 392.24; p = 0.00, RMSEA = 0.041 (90% C.I. 0.031, 0.050); p = 0.99]. As expected, the paths to decisional conflict were significant for post-intervention MSI pros (t = −2.43; p < 0.05), MSI cons (t = 2.78; p < 0.05), and preparedness (t = −7.27; p < 0.01). Less decisional conflict was reported by those reporting more MSI pros, better preparedness, and fewer MSI cons. However, while post-intervention IHC knowledge predicted greater decisional self-efficacy, the latter did not predict decisional conflict. Our model had a lower (i.e. a better fit) AIC(23) than an alternate model in which decisional conflict predicted MSI pros, MSI cons, and preparedness.

Figure 2.

Results of Structural Equation Model of Associations between Knowledge, Attitudes, and Decisional Conflict

Discussion

The structural equation model explained 47% of the variance in decisional conflict suggesting that the intervention along with knowledge and decisional processes played a strong role in predicting conflict. The intervention increased MSI knowledge which, in turn, influenced preparedness and pros, and both knowledge and preparedness mediated associations with decisional conflict. In this context, obtaining knowledge helped patients feel more prepared to make the decision and to appreciate the possible benefits of the MSI test.

However, our hypothetical model was not completely supported by the data. First, although MSI cons contributed to decisional conflict, neither the intervention nor MSI and/or IHC knowledge reduced perceived cons. One possible explanation is that the content of the CD-ROM did not address some testing barriers such as the lack of desire to learn about familial risk and concerns about insurance discrimination. A second way the model was not supported regarded associations among the intervention, IHC knowledge, and self-efficacy. The intervention increased IHC knowledge which then increased self-efficacy. However, neither IHC knowledge nor self-efficacy was associated with other decisional processes or decisional conflict. Two contributing factors may include that there was less informational content about IHC in the CD-ROM, and that the pros, cons, and preparedness items asked about MSI testing, making IHC knowledge a less critical component of the decision-making process evaluated here.

In terms of limitations, although our approach was strengthened by the incorporation of longitudinal data, any approach that searches for a best fitting model by using modification indices such as SEM is susceptible to capitalization on chance (24). Replication with another sample would be necessary. Also, because decisional conflict and follow-up mediator variables were measured at the same time point, causality cannot be proven but only inferred by the superior AIC of the final model. Although we tested an alternative model which did not fit as well as the proposed model, it is still possible that reduced decisional conflict leads to increased perceptions of preparedness and greater pros. Important limitations to the study's sample also exist as it is not representative of the US cancer population by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and treatment at an academic medical center.

Our results suggest that DAs affect decisional conflict through multiple pathways including knowledge-dependent and knowledge-independent paths, attitude changes, and improved feelings of preparation. Further research to understand the importance of different pathways while varying decisional context (difficult vs easy) and the decision maker (educated vs uneducated) may better elucidate the decision process. Future DAs may also have a greater impact if content addressed more barriers. As noted by Farrell and colleagues (25), attitudes about testing should be taken into account when counseling patients about test benefits and risks. From a clinical perspective, these findings illuminate the important role of knowledge, preparedness, and perceived benefits of testing in reducing uncertainty in the decision making context.

Acknowledgments

Funded by grant CA109332 from the National Cancer Institute and P30 CA006927 to Fox Chase Cancer Center, and by an Established Investigator in Cancer Prevention and Control Award to Sharon Manne by the NCI (K05 CA109008). We would like to thank Mary Daly, Jason Driesbaugh, Zhora Catts, Maryann Krayger, Deborah Lee, Cheri Manning, Kristen Shannon, Hetal Vig, Marianna Silverman, Stacy McConnell, and Sara Worhach. We also thank the physicians at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Christiana Care Health System for referring patients to this study.

References

- 1.Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(4):261–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology Policy statement update: Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21:2397–2406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Annas GJ. The rights of patients. 3. New York: NYU Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manne SL, Chung DC, Weinberg DS, et al. Knowledge and attitudes about microsatellite instability testing among high-risk individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(10):2110–7. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwhistle W, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D, Holmes-Rovner M. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decision. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(2):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green MJ, Peterson SK, Baker MW, et al. Effect of a computer-based decision aid on knowledge, perceptions, and intentions about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(4):442–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mancini J, Nogues C, Adenis C, et al. Impact of an information booklet on satisfaction and decision-making about BRCA genetic testing. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(7):871–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Connor A, Drake E, Fiset V, Graham I, Laupacis A, Tugwell P. The Ottawa patient decision aids. Effective Clin Pract. 1999;2:163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor AM. Decisional conflict. 2. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolan J, Frisina S. Randomized controlled trial of a patient decision aid for colorectal cancer screening. Med Decis Making. 2002;22(2):125–39. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0202200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer. JAMA. 2004;292:435–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephens RL, Xu Y, Volk RJ, et al. Influence of a patient decision aid on decisional conflict related to PSA testing: a structural equation model. Health Psych. 2008;27(6):711–21. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manne SL, Meropol NJ, Weinberg DS, et al. Facilitating informed decisions regarding microsatellite instability testing among high-risk individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(8):1366–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laupacis A, O'Connor A, Drake E, et al. A decision aid for autologous pre-donation in cardiac surgery- A randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:458–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride C, Bastian L, Halabi S, et al. A tailored intervention to aid decision making about hormone replacement therapy. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92:1112–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.7.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasen HF, Mecklin JP, Khan PM, Lynch HT. The International Collaborative Group on Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rect. 1991;34(5):424–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02053699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lerman C, Biesecker B, Benkendorf JL, et al. Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(2):148–57. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunn H, O'Connor A. Validation of client decision-making instruments in the context of psychiatry. Can J Nursing Res. 1996;28(3):13–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry M, Cherkin D, Chang Y, Fowler F, Skates S. A randomized trial of a multimedia shared decision-making program for men facing a treatment decision for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Dis Management Clin Outcomes. 1997;1:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connor AM. Decisional Conflict Scale. 4. Ottawa: Loeb Health Research Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akaike H. Information theory as an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Akademiai Kiado; Budapest: 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacCallum R, Roznowski M, Necowitz L. Model specifications in covariance structure analysis: The problem of capitalization on chance. Psychol Bulletin. 1992;111:490–504. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell M, Murphy M, Schneider C. How underlying patient beliefs can affect physician patient communication about prostate specific antigen testing. Effect Clin Pract. 2002;5:120–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]