Abstract

Functional neuroimaging relies on the robust coupling between neuronal activity, metabolism and cerebral blood flow (CBF) to map the brain, but the physiological basis of the neuroimaging signals is still not well understood. Here we applied a pharmacological approach to separate spiking activity, synaptic activity, and the accompanying changes in CBF in rat cerebellar cortex. We report that tonic synaptic inhibition achieved by topical application of γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) (muscimol) or GABAB (baclofen) receptor agonists abolished or reduced spontaneous Purkinje cell spiking activity without affecting basal CBF. The magnitude of CBF responses evoked by climbing fiber stimulation decreased gradually over time after exposure to muscimol, being more pronounced in the superficial than in the deep cortical layers. We provide direct evidence in favor of a laminar-specific regulation of CBF in deep cortical layers, independent of dilatation of surface vessels. With prolonged exposure to muscimol, activity-dependent CBF increments disappeared, despite preserved cerebrovascular reactivity to adenosine and preserved local field potentials (LFP). This dissociation of CBF and LFPs suggests that CBF responses are independent of extracellular synaptic currents that generate LFPs. Our work implies that neuronal and vascular signals evoked by glutamatergic pathways are sensitive to synaptic inhibition, and that local mechanisms independent of transmembrane synaptic currents adjust flow to synaptic activity in distinct cortical layers. Our results provide fundamental insights into the functional regulation of blood flow, showing important interference of GABAA receptors in translating excitatory input into blood flow responses.

Variations in neuronal activity are accompanied by robust changes in brain metabolism or perfusion (1). This relationship is exploited by functional neuroimaging techniques that use changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) or in the blood-oxygenation level-dependent signal (BOLD) to track brain function. Recently, we reported that combined electrical stimulation of two neuronal networks, one excitatory and one inhibitory, in the cerebellar cortex projecting to the same target cell produced changes in CBF and local field potentials (LFP) that were context sensitive (2). Our work implied that hemodynamic changes evoked by activation were driven by subthreshold synaptic activity and, in particular, that the balance between synaptic excitation and inhibition, as well as the electroresponsive properties of the targeted nerve cells themselves, controlled the amplitudes of the neuronal and vascular signals. In that study, we used stimulation of the cerebellar parallel fibers to produce strong synaptic γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic inhibition of the Purkinje cells (PCs) that produces a clear dissociation of the CBF response from the spiking activity in the cerebellar cortex (3). The idea of dissociating spikes, synaptic activity, and signals used in functional neuroimaging is essential to understand its neurophysiological basis (4–6). One limitation of our approach is that this type of inhibitory stimulation is possible only in the cerebellar cortex because of its unique neuronal organization. We aim to study the influence of inhibition in other brain regions as well, but this requires an experimental protocol that is independent of the local neuronal network. We here report the feasibility of an approach to study the influence of inhibition in the cerebellar cortex by replacing the net inhibitory input to PCs from parallel fiber (PF) stimulation with topical application of GABA agonists. The applicability of the presented approach to other brain regions is presently being examined in a separate study.

Our main findings were that topical application of the GABAA agonist, muscimol, resulted in the dissociation of PC spiking and CBF under nonstimulated (basal) conditions, and of synaptic activity and CBF under stimulated conditions. The effect of baclofen, a GABAB agonist, was less pronounced. The study disclosed independent laminar control of CBF and suggests that changes in CBF to excitatory input are strongly influenced by synaptic inhibition.

Methods

Experiments were performed in 24 male Wistar rats (250–350 g). All studies were in full compliance with the guidelines set forth in the European Council's Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes and were approved by the Danish National Ethics Committee.

Anesthesia was induced by halothane (Vaporizer, Fluotec 3 Cyprane, Keighley, U.K.; 3.5% induction, 1.5% surgery, and 0.7% maintenance) or isoflurane (Vaporizer 19.3, Drägerwerk AG, Lübeck, Germany; 5.0% induction, 2.0% surgery, and 2.0% maintenance) in 30% O2/70% N2O. The corneal reflex and response to toe or tail pinch were used to monitor the level of anesthesia. The trachea was cannulated for mechanical ventilation and catheters were placed into the left femoral artery and vein, which were continuously perfused with physiological saline. Continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure and hourly blood samples of arterial pH, pO2, and pCO2 assured maintenance of basic physiological parameters. The head was fixed in a stereotaxic frame. We used an open cranial window preparation as described (2). The brain was superfused continuously with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at 37°C, aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (123.00 mM NaCl/2.8 mM KCl/22.00 mM NaHCO3/1.45 mM CaCl2/1.00 mM NaHPO4/0.876 mM MgCl2/3.00 mM glucose). A small craniotomy exposed the vermis region, and the dura was carefully removed.

Electrophysiological Recordings. We used single-barreled glass microelectrodes filled with 2 M saline (impedance, 2–3 MOhm; tip, 2 μm). Single unit activity (spikes) and extracellular LFP of PCs were recorded with a single glass microelectrode at a depth of 300–600 μm in the cerebellar cortex of vermis segments 5 or 6. An Ag/AgCl ground electrode was placed in the neck muscle. The preamplified (×10) signal was A/D converted, amplified, and filtered (spikes, 300–2,400 Hz bandwidth; LFP, 1–1,000 Hz bandwidth), and digitally sampled by using the 1401plus interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, U.K.) connected to a personal computer running the SPIKE 2.3 software (Cambridge Electronic Design). Digital sampling rates were at 20 kHz for spikes and 5 kHz for LFP.

Climbing Fiber (CF) Stimulation. A coated, bipolar stainless-steel electrode (SNEX 200, RMI, Woodland Hills, CA, 0. 25-mm contact separation) was stereotaxically lowered into the caudal part of the inferior olive as described (2). Positioning was optimized by means of the maximal response of LFP in the cerebellar vermis region to continuous low-frequency stimulation (0.5 Hz). Pulses of 200-μs constant current with an intensity of 0.15 mA (ISO-flex, AMPI, Jerusalem) were used at 2, 5, and 10 Hz for 30 s.

PF Stimulation. A coated, bipolar stainless-steel electrode of the same make as above was also used for PF stimulation. The electrode was carefully positioned to lightly touch the surface of the vermis. The recording glass microelectrode and the laser-Doppler flowmetry (LDF) probe were placed “on-beam” in close proximity to the stimulating electrode. Pulses of 200-μs biphasic current with an intensity of 1.50 mA (ISO-flex) were used at frequencies of 0.5 and 30 Hz for 30 s. To record field potentials, we used the stimulus frequency of 0.5 Hz because stimulation at this low frequency resulted in large and reproducible LFPs, optimally describing the total extracellular current in the area examined. To record large and reproducible CBF responses during parallel fiber stimulation, we used the stimulus frequency of 30 Hz.

Drug Application. Agonists were applied to the vermis by topical superfusion. We used muscimol to activate GABAA receptors and baclofen to activate GABAB receptors. Each drug was dissolved in artificial CSF at a concentration of 0.2 mM. Adenosine (0.1 mM) was applied for 5 min before and after the experiment to demonstrate the unchanged reactivity of the vasculature.

Laser-Doppler Measurements. CBF was recorded by using a double-wavelength LDF probe employing green and red laser light (custom made, Perimed, Stockholm; green channel, 543-nm wavelength with 140-μm fiber separation; red channel, 780-nm wavelength with 250-μm fiber separation). Because of the physical properties of laser light and the geometry of the LDF probe, the channel employing green laser light registered CBF in the upper cortex down to a depth of 250 μm, whereas the channel employing red laser light measured CBF down to a depth of 1,000 μm. The probe was placed on the cortical surface of a region devoid of large vessels (>100 μm) as close as possible to the registering microelectrode. The LDF signal was sampled at 10 Hz, A/D converted (Periflux 4001 Master, Perimed, Sweden), and recorded by using SPIKE 2.3 software (Cambridge Electronic Design).

Data Analysis and Statistics. Values are expressed as means ± SEM, with levels of significance determined by Wilcoxon matched pairs test between groups. Changes were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Shape and amplitude identified PC spikes before data acquisition. Automatic online and offline spike sorting was used to remove noise contributions to the calculated spiking rate (SPIKE 2.3 software). The LFPs were averaged and amplitudes were calculated as the difference between peak and baseline, defined as the mean of the 15 ms before stimulation onset.

Results

Effects of GABAA and GABAB Receptor Activation on Cerebellar PC Spike Rate and Basal CBF. The effect of tonic synaptic inhibition on electrical activity and blood flow in the cerebellar cortex was detected by extracellular recordings of activity of individual PCs (spike rate) or groups of neurons (LFP), combined with laser Doppler flowmetry on a real time basis. The specific GABAA agonist muscimol and GABAB agonist baclofen were used to elicit tonic inhibition.

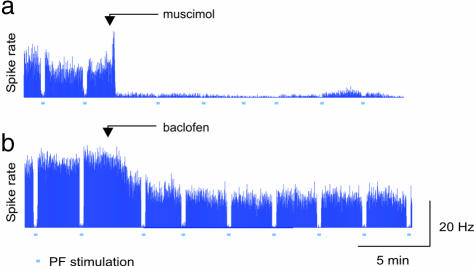

Muscimol reduced the spontaneous spike rate by 93 ± 2% of control levels within 30 seconds of application (Fig. 1a) in five of six rats, whereas the spike rate in the last rat decreased by 43%. Baclofen application reduced the spontaneous spiking level by 49 ± 6% of the control level (see Fig. 1b) in four of six rats. In two rats, the basal spiking rate was too unstable for a proper quantification. In all rats, the basal CBF level remained constant during the entire period of drug application for both muscimol and baclofen, demonstrating that pharmacologically relevant doses of GABAA and GABAB agonists have no effect on the baseline level of CBF. The data suggest that basal CBF is independent of neuronal signaling.

Fig. 1.

GABA receptor activation decreased spontaneous spike activity in PCs. (a) GABAA receptor activation by topical application of 0.2 mM muscimol (starting point indicated by arrow) abolished spontaneous spike activity with 93 ± 2% (n = 5). (b) Activation of GABAB receptors reduced the spontaneous spike rate by 49 ± 6% (n = 4). Horizontal bars indicate periods of PF stimulation. Synchronized stimulation of parallel fibers results in net inhibition of the PCs due to the release of GABA from the inhibitory stellate and basket cells. This inhibition is similar to the inhibition achieved by GABAA receptor activation (Upper) and can transiently shut down PC spiking on top of the GABAB receptor activation.

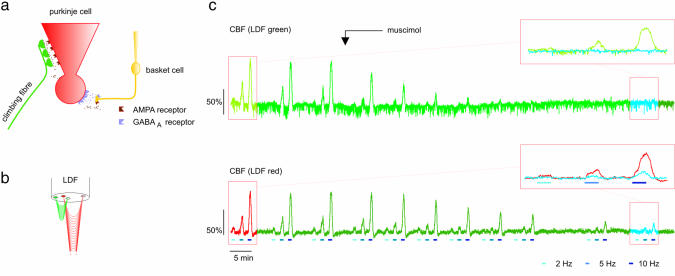

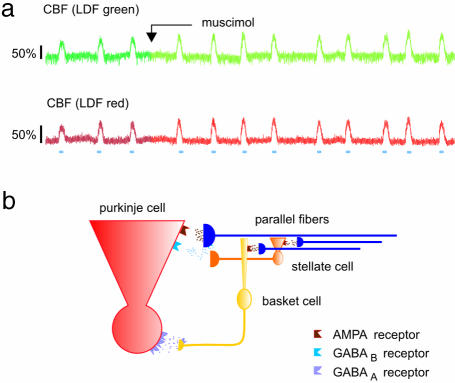

LFPs and Evoked Increases in CBF in the CF–PC System. Climbing fibers project to the proximal dendrites of PCs (Fig. 2a) and elicit a large, all-or-none excitatory postsynaptic potential that is recorded as the LFP. The presynaptic action potentials in the CFs do not contribute significantly to the amplitude of the LFP because of the slenderness and low density of these structures (7). CF activation also mediates heterosynaptic presynaptic inhibition of basket cells via an α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor. This results in inhibition of GABA release and is proposed to reinforce transmission of the afferent input from CF to PCs (8). CF stimulation at 2, 5, and 10 Hz evoked LFP amplitudes of 4.1 ± 0.5, 4.3 ± 0.7, and 5.2 ± 0.4 mV, respectively, under control conditions (n = 7). Blood flow responses were recorded with a two-channel laser probe containing both green and red laser light for blood flow measurements in different depths (Fig. 2b; see Methods). The corresponding CBF responses amounted to 15.5 ± 1.7, 53.6 ± 11.7, and 92.0 ± 17.6% of baseline (n = 12) as monitored with the green LDF channel, and 18.6 ± 2.3, 57.7 ± 10.8, and 90.4 ± 13.1% of baseline (n = 12) as monitored with the red LDF channel.

Fig. 2.

Magnitude of evoked increases in CBF was gradually reduced after GABAA-receptor activation. (a) Diagram showing neural elements including receptors for AMPA and GABAA in the CF–PC network. (b) Drawing of the two-channel LDF probe (LDFgreen and LDFred) that recorded blood flow (CBF) to depths of 250 μm and 1,000 μm, respectively. (c) Original sample trace of CBF in response to CF stimulation during control stimulations and after topical application of muscimol (starting point indicated by arrow). (Upper) CBF measured with LDFgreen. (Lower) CBF measured with LDFred. Evoked CBF responses at 2, 5, and 10 Hz (indicated by colored bars) were gradually reduced over time after exposure to muscimol. Red boxes to the upper right of each CBF trace depict an expanded superimposition of the marked stimulation sequences from the original traces. Red or green trace represents CBF during control, and blue trace represents CBF after exposure to muscimol.

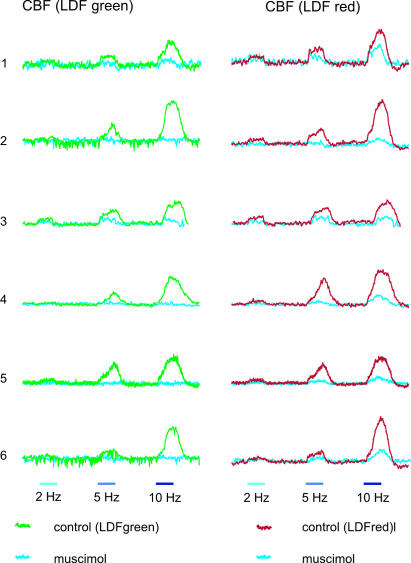

GABAA Receptor Activation Unmasks Layer Specificity of Evoked CBF Responses. In the presence of muscimol, the magnitude of evoked CBF responses diminished gradually over time (Fig. 2c). In all rats studied, this reduction occurred more rapidly in the superficial layer of the cortex (n = 6; P < 0.05; Fig. 3). Superimposed traces of evoked CBF responses at 2, 5, and 10 Hz measured before and after 50 min of exposure to muscimol show that four of the six rats exhibited complete abolition of the evoked CBF responses in the upper cortical layer (green channel) while having a preserved, albeit small, CBF response in the deeper layer (red channel) (Fig. 4). This finding suggests that local mechanisms adjust flow to match synaptic activity in distinct cortical layers.

Fig. 3.

Time course of reduction of evoked CBF increases at 2, 5, and 10 Hz measured with LDFgreen (Upper) and LDFred (Lower). Graphs show that evoked changes in CBF were reduced faster in the upper layer of the cortex as compared to the deeper layer. Each point represents the mean ± SEM. (n = 6).

Fig. 4.

Superimposition of individual traces of CBF responses obtained for each animal. (Left) Measurements obtained with LDFgreen. (Right) Measurements obtained with LDFred. Green trace in Left and red trace in Right represent increases in CBF in response to control stimulations, and blue traces in both panels represent CBF responses to the same stimulations 50 min after muscimol application.

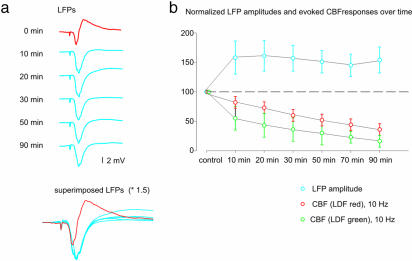

Dissociation of LFPs and Evoked CBF Responses in the CF–PC System. The amplitude and profile of the evoked LFPs changed immediately in response to muscimol application as indicated in Fig 5a. The late positive wave disappeared, whereas the negative phase increased in amplitude (see superimposed LFPs in Fig. 5a). No further alterations in the LFP occurred over time. The comparative time course of effect of muscimol on field potentials and CBF are summarized in Fig. 5b and show a clear dissociation between LFPs and changes in CBF after exposure to muscimol.

Fig. 5.

GABAA-receptor activation dissociated LFPs and CBF responses evoked by CF stimulation. (a) Averaged traces of control and conditioned LFPs in response to CF stimulation (n = 6). Red trace represents averaged LFPs during control stimulation; blue traces represent averaged LFPs during stimulation at different time points after drug application. All traces are superimposed below. (b) Comparative time course of normalized LFP amplitudes and normalized changes in CBF evoked at 10 Hz.

In the presence of baclofen, the amplitudes of the evoked LFPs and CBF responses remained constant during climbing fiber stimulation (Table 1). Increasing the concentration of baclofen from 0.2 mM to 1 mM in two rats did not change this result (data not shown).

Table 1. Effect of GABA receptor agonists on CBF responses and LFP amplitudes during CF and PF stimulation.

| Data set | Control | Muscimol | Control | Baclofen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | ||||

| CBF increase (LDF green, 10 Hz), % | 92.0 ± 17.6 | 45.3 ± 7.6* | 66.5 ± 8.0 | 58.2 ± 11.2 |

| LFP amplitude (2 Hz), mV | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 1.3* | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

| PF | ||||

| CBF increase (LDF green, 10 Hz), % | 41.4 ± 5.2 | 45.3 ± 7.6 | 39.6 ± 8.6 | 38.1 ± 5 |

| LFP amplitude (2 Hz), mV | 0.51 ± 0.1 | 0.53 ± 0.2 | 0.39 ± 0.2 | 0.72 ± 0.3* |

, P < 0.05

LFPs and Evoked Increases in CBF in the PF–PC System. We then assessed the effects of tonic inhibition on the LFPs and CBF responses evoked by stimulation of the cerebellar PFs. Fig. 6a depicts CBF traces recorded from one animal during intermittent stimulation at 30 Hz showing similar CBF responses before (41.4 ± 5.2%) and after (45.3 ± 7.6%) application of muscimol (P > 0.5; n = 7). In separate experiments, we also examined the effect of muscimol on CBF responses evoked by PF stimulation at 5 Hz and 10 Hz and found no effect at these lower frequencies either (data not shown). Nor did muscimol affect LFP amplitude or shape during PF stimulation (Table 1). Baclofen activates GABAB receptors located both presynaptically on parallel fibers and postsynaptically on PC dendrites at the site of synaptic input from the parallel fibers (Fig. 6b). Baclofen had no effect on the evoked CBF responses, but did have a slight effect on the LFP amplitude, which increased from 0.4 ± 0.2 mV to 0.7 ± 0.3 mV (P = 0.02, n = 4, Table 1). Finally, we observed that tonic synaptic inhibition had no effect on cerebrovascular reactivity because the CBF responses to topical application of 0.1 mM of adenosine remained constant in the presence of muscimol and baclofen as compared to baseline conditions.

Fig. 6.

No effect of muscimol on CBF in the PF–PC pathway. (a) Original traces of CBF during control stimulations and after topical application of muscimol (starting point indicated by arrow) measured with LDFgreen (Upper) and LDFred (Lower) in response to PF stimulation. Horizontal bars indicate stimulation periods. (b) Diagram showing neural elements including receptors for AMPA, GABAA, and GABAB in the PF–PC network.

Discussion

One of the most exciting issues in basic neurophysiology of functional neuroimaging is the relationship between excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity in activated brain regions, the resulting neuronal firing and synaptic activity, and the associated vascular and metabolic signals (5, 6). In this study we explored the effect of inhibition on the vascular coupling by using topical application GABA agonists.

The inhibitory GABAergic synapses at PCs are endowed with ionotropic GABAA receptors and metabotropic GABAB receptors (see Figs. 2a and 6b) (9, 10). GABAA receptor activation results in the opening of a chloride conductance leading to a fast inhibitory postsynaptic potential that provides robust suppression of neuronal output with fast temporal control (11). GABAB receptor activation decreases neuronal excitability by opening G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (12, 13), which provides more prolonged inhibitions with long latencies by increasing the threshold for spiking (14, 15).

Our findings are consistent with these events: muscimol application abolished PC spiking activity completely within tens of seconds, whereas baclofen resulted in a reduction of PC spiking activity, which was variable in magnitude. Thus, GABAB receptor activation fine-tuned the excitability of PC dendrites rather than producing overall inhibition. This finding is strongly supported by the conclusions of others who have examined the role of GABAB receptors in the cerebellar cortex (11, 16, 17).

The baseline level of CBF remained constant in the presence of the two GABA agonists despite the reduction or the abolishment of PC spiking. This finding suggests that GABA agonists in vivo have no influence on the cerebral vessels and that production of action potentials contributes little to basal CBF, if indeed contributing at all. It should be noted that spikes were recorded from PCs only, whereas spiking activity of the inhibitory interneurons was not recorded. However, because interneurons possess autoreceptors for GABA, we presume that outgoing spike activity from interneurons and PCs was blocked equally during exposure to muscimol. Our finding of a clear dissociation between spikes and basal CBF is consistent with our recent report showing that strong deactivation of cerebellar PCs by functional ablation of the contralateral cerebral cortex had no or only minimal effect on basal CBF in the contralateral cerebellar hemisphere (18). The lack of effect of the GABA agonists on basal CBF is consistent with studies showing that bicuculline and picrotoxin, powerful inhibitors of GABAA receptors, have no effect on basal or evoked increases in CBF despite proven synaptic disinhibition in the cerebellar cortex (3, 19). Our data are at variance with a report that showed that penetrating arterioles in hippocampal slices dilated in response to GABA or muscimol, whereas constricting in response to baclofen (20). However, vessels in slices are not pressurized and are therefore without vascular tone, which might be essential if in vitro data are to be extrapolated to in vivo conditions. On this background, we question a direct regulatory role for GABA on cerebral blood vessels.

GABA Receptor Activation in the CF–PC System. During synaptic inhibition by GABAA receptor activation, the amplitude of the LFPs evoked by CF stimulation increased while the shape changed slightly. The amplitude of a synaptic current depends on the synaptic driving force, i.e., the distance of membrane potential from the synaptic reversal potential (21). Opening of a chloride conductance in response to GABAA receptor activation hyperpolarizes the cell and increases the driving force for the transmembrane synaptic currents as the reversal potential for chloride is ≈-72 mV (12). This may result in larger extracellular synaptic currents in response to CF stimulation and consequently larger LFPs.

Normally, there is a tight coupling between synaptic activity, i.e., LFPs on the one hand, and evoked CBF responses (3, 22, 23) and BOLD signals (24) on the other. The transmembrane synaptic current may represent the metabolic “workload” that triggers the rise in CBF and in turn the BOLD signal. However, we found that the CBF response to CF stimulation gradually diminished with continued exposure to muscimol despite the increased amplitude of the LFPs. This dissociation between synaptic activity and CBF responses in face of preserved vascular reactivity supports the view of a more complex relation that is independent of current flow in the extracellular space.

An inherent property of the CF–PC pathway is that CF stimulation under normal conditions evokes large and widespread increases in intracellular calcium in PC dendrites, whereas under conditions of synaptic inhibition, these increases are spatially restricted and small, or even absent (25–27). We postulate that the absence of an intracellular increase in calcium could form the basis for the uncoupling of synaptic activity and CBF in the CF system under conditions of tonic synaptic inhibition: lack of a [Ca2+]i increase during CF stimulation might attenuate downstream signaling pathways crucial for the production and release of substances that mediate the vascular reaction. Signaling to the Bergman glial cells could also be attenuated because the astrocyte is considered to be a key player in the coupling of synaptic activity and CBF (28, 29). Our hypothesis is consistent with the fact that NO and cyclooxygenase products, which mediate part of the CBF increment evoked by stimulation (30–32), depend on phasic rises in [Ca2+]i (33, 34). Future studies could address this issue by direct measurements of changes in [Ca2+]i in response to activation of the structures examined in the present study. Furthermore, the dissociation between LFP and CBF may imply a dissociation of neurometabolic coupling as well, which could affect BOLD- and CBF-based neuroimaging methods differentially. Pet measurements (CMRO2 plus CBF) or MRI-based approaches measuring BOLD and CBF simultaneously could be used to elucidate whether this is the case.

During prolonged exposure to muscimol, the CBF response to CF stimulation disappeared in the superficial cortical layers (0–250 μm), whereas a local response, albeit attenuated, still remained at the cortical depth of 250–1,000 μm. This finding points toward a layer-specific regulation of CBF and is intriguing in view of recent studies by others and ourselves that describe the distribution of stimulus-evoked changes of BOLD or CBF responses within specific cortical layers by using fMRI or laser-Doppler techniques with high temporal resolution (35, 36). The observation that a local increase in CBF may exist at a certain cortical depth without any rises in CBF in the layers superficial to that level is counterintuitive: stimulus-evoked dilatation of surface arterioles with initial filling of superficial layers is thought to be a prerequisite for activity-dependent CBF increases in deeper layers. Our present finding of a layer-specific regulation of CBF may be explained by pericytes at precapillary arterioles believed to regulate capillary blood flow (37, 38) or by local dilatation of type III cortical arterioles that penetrate deep within the cortex without contributing to the superficial capillary network (38, 39). We expect that real-time studies of the laminar distribution of evoked hemodynamic responses will prove useful in the identification of the vascular mechanisms that underlie both CBF and BOLD signals.

Baclofen had no effect on the LFP amplitude evoked by CF stimulation. This is consistent with the preserved excitability of PCs in the face of GABA activity (14) and the fact that there is no documentation for a physiological role of the GABAB receptor in the CF system in vivo. Nevertheless, the effect on the spontaneous spike rate suggests that baclofen does have an effect on neuronal excitability, possibly by limiting the spatial extent of the excitatory afferent input.

GABA Receptor Activation in the PF–PC System. Evoked CBF responses and LFP amplitudes in response to PF stimulation were not affected by topical application of muscimol. This may be explained by occlusion, i.e., exogenous GABA does not add to the response properties of the PF–PC system in which synchronized stimulation of the parallel fibers results in net-inhibition of the PCs due to the release of GABA from the inhibitory stellate and basket cells (7). Thus, occupation of GABAA receptors by muscimol does not contribute further to the inhibition induced by PF stimulation (see Fig. 1). The CBF increase evoked by PF stimulation is partially mediated by other mechanisms than the CBF response evoked by CF stimulation (3). A substantial part of the CBF increase evoked by PF stimulation is caused by excitation of the inhibitory interneurons that are present at high density with an estimated 16–17 stellate cells present for each PC (40). The activity-dependent increases in [Ca2+]i in interneurons may still be present during exposure to muscimol and thus account for the unaltered CBF response. Also, the inhibitory effect of muscimol on the calcium influx into the PC is less pronounced in response to PF stimulation compared to CF stimulation (26). The evoked LFPs in response to PF stimulation were unaffected by the simultaneous presence of the GABAA agonist.

Baclofen did induce a slight increase in the LFP amplitude compared to control conditions but had no effect on CBF. Presynaptic PF terminals are endowed with GABAB receptors that function to reduce the synaptic release of glutamate. However, in vitro and at low concentrations, baclofen augments mGluR1-mediated excitatory synaptic currents produced by PF stimulation and enhances mGluR1-mediated excitatory transmission at PF–PC synapses (41). Conversely, in vivo studies reveal a weak inhibitory potency of baclofen in the cerebellar cortex (16). Thus, the effect of baclofen is complex, but the slight increase in the LFP amplitude observed in this work is not explained by data from the literature.

In conclusion, here we provide evidence that topical application of GABA receptor agonists to the cerebellar cortex makes it feasible to study the coupling between synaptic activity and CBF in the absence of spontaneous or evoked postsynaptic spike activity with preserved afferent input function. We suggest that the different effects of the GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists observed relate to the functional anatomy of the neuronal circuits and the different mechanisms of action of the two receptors. We postulate that the amplitude of the CBF responses is controlled by vascular mechanisms that are distributed across the cortex in accordance with the known functional anatomy of the cerebral vasculature. We further postulate that, in the cerebellum, the amplitude of the CBF responses are not directly dependent on the extracellular synaptic currents, and we suggest that cellular mechanisms downstream from synaptic excitation, possibly rises in intracellular messengers such as Ca2+, trigger the synthesis of the substances that constitute the basis of the neurovascular coupling in the pure glutamatergic CF–PC system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lillian Grøndahl for expert technical assistance. This study was supported by The Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish Medical Research Council, and The NOVO-Nordisk Foundation.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CBF, cerebral blood flow; CF, climbing fibers; LFP, local field potentials; PF, parallel fibers; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; BOLD, blood-oxygenation level-dependent; LDF, laser-Doppler flowmetry; PC, Purkinje cell.

References

- 1.Raichle, M. E. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 765-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caesar, K., Gold, L. & Lauritzen, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 4239-4244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathiesen, C., Caesar, K., Akgoren, N. & Lauritzen, M. (1998) J. Physiol. 512, 555-566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith, A. J., Blumenfeld, H., Behar, K. L., Rothman, D. L., Shulman, R. G. & Hyder, F. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10765-10770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logothetis, N. K. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 3963-3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauritzen, M. & Gold, L. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 3972-3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eccles, J. C., Ito, M. & Szentågothai, J. (1967) The Cerebellum as a Neuronal Machine (Springer, New York).

- 8.Satake, S., Saitow, F., Yamada, J. & Konishi, S. (2000) Nat. Neurosci. 3, 551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilkin, G. P., Hudson, A. L., Hill, D. R. & Bowery, N. G. (1981) Nature 294, 584-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowery, N. G., Hudson, A. L. & Price, G. W. (1987). Neuroscience 20, 365-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreurs, B. G., Sanchez-Andres, J. V. & Alkon, D. L. (1992) Brain Res. 597, 99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaneda, M., Wakamori, M. & Akaike, N. (1989) Am. J. Physiol. 256, C1153-C1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sodickson, D. L. & Bean, B. P. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 6374-6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connors, B. W., Malenka, R. C. & Silva, L. R. (1988) J. Physiol. 406, 443-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batchelor, A. M. & Garthwaite, J. (1992) Eur. J. Neurosci. 4, 1059-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Billard, J. M., Vigot, R. & Batini, C. (1993) Neurosci. Res. 16, 65-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vigot, R. & Batini, C. (1997) Neurosci. Res. 29, 151-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold, L. & Lauritzen, M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7699-7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, J. & Iadecola, C. (1994) Neuropharmacology 33, 1453-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fergus, A. & Lee, K. S. (1997) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 17, 992-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaeger, D., De Schutter, E. & Bower, J. M. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 91-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngai, A. C., Jolley, M. A., D'Ambrosio, R., Meno, J. R. & Winn, H. R. (1999) Brain Res. 837, 221-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuura, T. & Kanno, I. (2001) Neurosci. Res. 40, 281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logothetis, N. K., Pauls, J., Augath, M., Trinath, T. & Oeltermann, A. (2001) Nature 412, 150-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Midtgaard, J., Lasserross, N. & Ross, W. N. (1993) J. Neurophysiol. 70, 2455-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Midtgaard, J. (1994) Trends Neurosci. 17, 166-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callaway, J. C., Lasser-Ross, N. & Ross, W. N. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 2777-2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zonta, M., Angulo, M. C., Gobbo, S., Rosengarten, B., Hossmann, K. A., Pozzan, T. & Carmignoto, G. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson, C. M. & Nedergaard, M. (2003) Trends Neurosci. 26, 340-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akgoren, N., Mathiesen, C., Rubin, I. & Lauritzen, M. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 273, H1166-H1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, G. & Iadecola, C. (1998) Stroke 29, 499-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dirnagl, U., Lindauer, U. & Villringer, A. (1993) Neurosci. Lett. 149, 43-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attwell, D. & Iadecola, C. (2002) Trends Neurosci. 25, 621-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauritzen, M. (2001) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 21, 1367-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen, A. & Lauritzen, M. (2001) J. Physiol. 533, 773-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva, A. C. & Koretsky, A. P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 15182-15187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ehler, E., Karlhuber, G., Bauer, H. C. & Draeger, A. (1995) Cell Tissue Res. 279, 393-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harrison, R. V., Harel, N., Panesar, J. & Mount, R. J. (2002) Cereb. Cortex 12, 225-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duvernoy, H., Delon, S. & Vannson, J. L. (1983) Brain Res. Bull. 11, 419-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito, M. (1984) The Cerebellum and Neural Control (Raven, New York).

- 41.Hirono, M., Yoshioka, T. & Konishi, S. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1207-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]