Abstract

The M2 proton channel from influenza A virus transmits protons across membranes via a narrow aqueous pore lined by water and a proton sensor, His37. Near the center of the membrane, a water cluster is stabilized by the carbonyl of Gly34 and His37, the properties of which are modulated by protonation of His37. At low pH (5–6), where M2 conducts protons, this region undergoes exchange processes on the microsecond to second timescale. Here, we use 2D IR to examine the instantaneous conformational distribution and hydration of G34, and the evolution of the ensemble on the femtosecond to picosecond timescale. The channel water is strongly pH dependent as gauged by 2D IR which allows recording of the vibrational frequency autocorrelation function of a 13C = 18O Gly34 probe. At pH 8, where entry and exit of protons within the channel are very slow, the carbonyl groups appear to adopt a single conformation/environment. The high-pH conformer does not exhibit spectral dynamics near the Gly34, and water in the channel must form a relatively rigid ice-like structure. By contrast, two vibrational forms of G34 are seen at pH 6.2, neither of which is identical to the high-pH form. In at least one of these low-pH forms, the probe is immersed in a very mobile, bulk-like aqueous environment having a correlation time ca. 1.3 ps at pH 6.2. Thus, protonation of His37 at low pH causes liquid-like water molecules to flow into the neighborhood of the Gly34.

Keywords: M2 channel influenza, transmembrane protein, water dynamics, infrared, two-dimensional

Transmembrane (TM) channels are ubiquitous and essential components of cells: They transport ions, water, or essential nutrients to and from and between cells (1). This paper focuses on the water molecules that are incorporated into such channels. Many configurations of water can be present, ranging from liquid-like, single-file, wire-like structures to various clusters in which the water density might be significantly reduced from that of the bulk (2). A more detailed experimental verification of these dynamic structures is needed. The three-dimensional hydrogen-bonded networks that define conventional liquid water undergo femtosecond timescale hydrogen-bond variation, exchange, and charge rearrangement processes. Although the channel water is not necessarily liquid, the dynamics of the water configurations that do occur may still be sufficiently transient that essential properties may not be exposed by conventional methods. Nevertheless, the mechanism of the transport requires knowledge of both the protein conformations and the properties of the confined water configurations. In most TM channels, the structures form by interactions of water molecules with the polar peptide units that line the interior of the channel. Such water structures can be defined by methods that allow the determination of structural features as a function of time, such as is the case for the two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy used in the present report.

Ultrafast Vibrational Responses

Ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy as used here is a unique approach to the challenge of characterizing the motions of water in the proton channel M2, which is described in the next section: It brings a unique perspective on the structural dynamics of the channel water. The 2D IR spectra create residue level images of both instantaneous conformational distributions as well as fast dynamics in proteins (3–6) by means of 13C = 18O labeling of helix backbone amide units (7, 8), which act as probes of local solvent spectral density through measures of the frequency–frequency correlation function of the amide-I vibration. The motion of water molecules around the amide groups in proteins and peptides causes fluctuations in the amide-I vibrational frequencies. The correlations of these fluctuations can be obtained from the 2D IR spectra, by identifying spectral changes as a function of the waiting time delay (T) between the second and third pulses of the nonlinear experiment. Frequency correlations of model amides and peptides in aqueous solution (9–11) have been shown to decay on a 1-ps timescale, similar to the main frequency relaxation process in liquid water (12–14). The isotope labeling strategies isolate the amide vibrational transitions of specific residues of the peptides without causing significant perturbation of the structure. Because the vibrational frequency of isotopically substituted amides depend mainly on their local environments, they act as probes of the microscopic structure and dynamics of fluctuating charges near different regions of the channel.

The M2 Proton Channel

The M2 channel is found in the influenza viruses. The channel is activated at low pH to transport protons across the membrane to acidify the viral interior—a process that is vital to the replication of the influenza A virus (15, 16). The protein is a homotetramer consisting of N-terminal, TM, and cytoplasmic domains. The 25 residue TM domain (M2TM), residues 22–46, forms four-helix bundles that conduct protons and bind amantadine, an antiviral drug that blocks the channel pore (17, 18). It is therefore a biologically relevant model for structural analyses and understanding the conduction mechanism of M2. Models of M2 have been based on mutagenesis (19), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (20–22), spectroscopic studies (23–25), and most recently from X-ray diffraction (26, 27) and solution NMR studies (28). Protonation of the His37 residues in the TM domain activates the protein to conduct protons (19). The high-resolution structures from NMR and X-ray diffraction show that M2 alters its conformation as the pH is reduced, and this change is correlated with conditions for transporting protons across the channel. The channel is suggested to be more accessible to the aqueous phase than to the viral interior at higher pH (22). The equilibrium is shifted toward a conformation which is more open to the viral interior on protonation of the His37 residues. This cycle must cause water to flow and ebb in the two gated conformations. One view has been that M2 is a classically gated channel, where protonation of His37 at low pH opens up a continuous pore occupied by a single water wire which can facilitate the transport of protons into the viral interior (29, 30). Another has suggested that His37 has a direct role in proton conduction by becoming protonated then deprotonated for every proton transported across the channel (19, 31–33). A kink in the helical structure close to Gly34 has been proposed to occur when the histidines become protonated (26, 34–36). This kink could disturb the hydrogen bonding of the Gly34 carbonyl to its neighboring N-H in the helical structure, making it possible for the C = O to form hydrogen bonds with the channel water. The mechanism whereby hydronium ions in water first form His+ states, which can then direct hydronium ions into the virus, remains a puzzle whose solution could unlock the key to a wide range of processes involving water and ions interacting with proteins.

The residue Gly34 is a pore lining residue in the TM domain of M2, whose conformation, dynamics, and hydration depend on protonation state of His37. The residues Gly34 and His37 are also conserved in all transmissible influenza M2 sequences. Fig. 1 illustrates the water structure in the vicinity of Gly34 in a 1.65-Å resolution X-ray structure of the protein at 100 K, probably in the +2 state (with two of the four His37 residues in the tetramer protonated) (27). Well-ordered water molecules bridge between Nδ of His37 and the carbonyl of Gly34 from a neighboring helix. An additional pair of waters bridge the opposite face of the His37 tetrad, forming hydrogen bonds to the Nε of the imidazoles. MD simulations suggest that this structure is partly maintained at room temperature; also solid-state NMR (SSNMR) (32, 37) of the TM domain of M2 in phospholipid bilayers shows that in frozen water the histidine–water hydrogen bonding is highly responsive to the degree of protonation of the four His37 residues. Water above the histidines (in the sense of Fig. 1), and therefore nearby to the Gly34, forms strong hydrogen bonds to Nδ of His37 at both low and high pH, whereas the more distal Nε of His37 associate strongly with water only at lower pH. It has also been suggested that a low-barrier imidazole-imdazolium hydrogen bond is present in the +2 state of M2, based on the presence of exchange broadening in the NMR spectrum, and this interaction breaks in the +3 state (25).

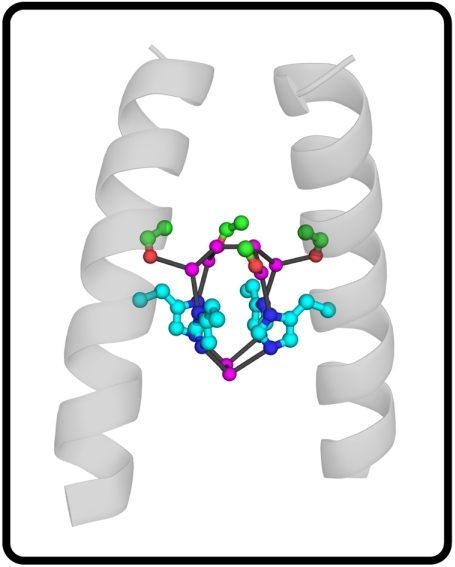

Fig. 1.

Structure of the M2 channel and associated water clusters from X-ray crystallographic experiments (Protein Data Bank ID 3LBW). Only two helices are shown for clarity. The water oxygens are shown in purple, the Gly34 residues in green, and the amide oxygen in red. The His37 residues are shown in light blue, and the ring nitrogens (Nδ and Nε) are shown in dark blue. The carbonyl oxygen and nearby water oxygens are connected by black lines.

Considerable evidence supports a proton conduction mechanism in which His37 alternates between different protonation states, most probably alternating between the +2 and +3 forms. Near neutral pH, the doubly protonated form predominates; as the pH on the outside of the virus (pHout) is lowered, protons enter the channel and generate the +3 state, which increases the hydration of the interior region of the channel. The increased hydration appears essential to allow protons to move from His37 into the interior of the channel, regenerating the +2 state and initiating another step in the conduction cycle. This increase in conformational heterogeneity of the +3 state has been studied at equilibrium by solution and SSNMR, which shows evidence for increased dynamics on the microsecond to millisecond timescale. However, it is difficult to characterize individual members of the conformational ensemble, given the dynamic processes involved. Two-dimensional IR, which provides information concerning the instantaneous conformational distribution as well as the hydration of Gly34 amide, is ideally suited to probe the process.

Here, we report linear and 2D IR experimental results on isotopically labeled (SSN24PLVVAASIIG∗34ILH37LILWILN44RL, where G* implies 13C = 18O substitution of the Gly34 amide carbonyl) and unlabeled M2TM (SSN24PLVVAASIIG34ILH37LILWILN44RL) in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles as a function of pH. Because the Asp carboxylate absorbs in the same region of the infrared as the 13C = 18O backbone isotope label, and has an extinction coefficient similar to that of an amide-1 transition (38), Asp24 and Asp44 were changed to Asn in this peptide. Also, the lack of other protonatable side chains in the sequence allows one to correlate spectral changes with changes in the protonation of His37. Both of these replacements are seen in natural variants of the protein, and the mutant D44N has been well characterized (39), because it is present in the Rostock form of the influenza A virus. This substitution increases the overall conduction of the channel and increases the activation and conduction pKa values by about 0.5 pKa units.

Results

Isolating the 13C = 18O Gly34 Probe Vibration.

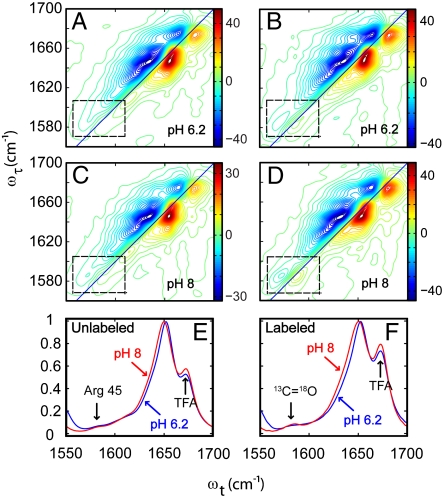

The linear IR spectra of the amide-1 region (Fig. 2 E and F) of the unlabeled and labeled peptides provide important baseline information because they identify significant changes with pH for M2TM. The Gly34 isotope label amide-I transitions are barely discernible as weak bands near 1,580 cm-1, in which region there is also background absorption from arginine (see SI Text). On the contrary, the 2D IR spectra of the 13C = 18O label are remarkable in their clarity as shown below.

Fig. 2.

Two-dimensional IR and linear FTIR spectra of labeled and unlabeled M2TM. (A and C) Two-dimensional IR spectra of unlabeled M2TM at pH 6.2 and pH 8, respectively. (B and D) Two-dimensional IR spectra of M2TM with C13 = O18 labeled Gly34 at pH 6.2 and pH 8, respectively. The dashed rectangle represents the C13 = O18 isotope transition region. (E and F) Linear FTIR spectra of unlabeled and labeled M2TM, respectively, at pH 6.2 and pH 8.

Two-Dimensional IR Reveals pH-Dependent Correlations in M2.

The overview 2D IR spectra shown in Fig. 2 A–D survey the same wide spectral region as displayed in the linear spectra (Fig. 2 E and F). The signals arise from the v = 0 → v = 1 transitions, shown as red in Fig. 2 A–D, and the oppositely signed v = 1 → v = 2 transitions, which are shown in blue. The presence of correlated frequency distributions is immediately evident in 2D IR spectra by the elongation of the signals along the diagonal. The amide-I 2D IR transitions of Arg45, seen clearly in the unlabeled spectra, and those of the 13C = 18O edited Gly34 residue are outlined as weak contour levels within the dashed rectangles near 1,585 cm-1 in Fig. 2 A–D. The signals from the labeled peptide in this highlighted region are dominated by the 13C = 18O amide-I transitions. The signal-to-noise ratio in these nonlinear experiments is such that enlargements of the highlighted spectral region in Fig. 3 show very robust spectral signatures of the protein conformations.

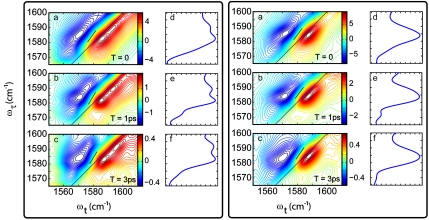

Fig. 3.

Two-dimensional IR spectra at three waiting times for pH 6.2 (Left) and pH 8 (Right). For each set (A–C), 2D IR spectra of the isotope label region at waiting times 0, 1, and 3 ps. The slopes are illustrated by black lines. The corresponding diagonal traces are plotted in D–F.

Fig. 3 shows the (13C = 18O) Gly34 tetramer band at two pH values and three selected waiting times. The differences with pH and waiting time are considerable: At pH 6.2, there are clearly two bands from the G34 label, whereas there is only one dominant band at pH 8. The ratio of the lower (1,581 cm-1) to higher (1,591 cm-1) frequency peak heights at pH 6.2 is 1.8 ± 0.2. At pH 8, the band is centered at 1,585 cm-1 and is distinct from the bands in the low-pH spectrum, indicating that together they represent three distinct conformations or configurations wherein the Gly34 is modified. The 2D IR spectra of the labeled peptide at pH 8 show negligible change in shape with increasing waiting times as is evident from Fig. 3. However, for the lower pH there is an obvious evolution of the 2D spectral shapes occurring on the picosecond timescale as seen in Fig. 3. The presence of picosecond time-dependent spectral changes of the labeled residue in the 2D IR spectrum are very likely to be caused by fluctuations in the amide-I mode frequency induced by movements of its surrounding water.

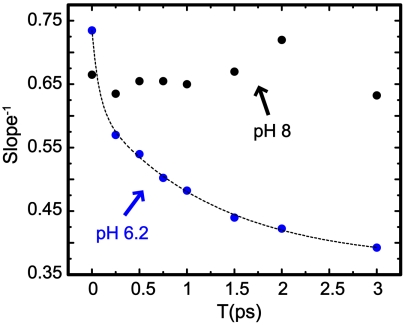

A semiquantitative measure of the spectral dynamics is the slope, S(T), of the nodal line separating the positive and negative contributions to the 2D IR spectrum (40) plotted as in Fig. 4 with ωt as the ordinate. (Additional details on the slope measurement are given in SI Text.) The most robust measures of S(T) at pH 6.2 are those for the conformation having the lower vibrational frequency peak (1,581 cm-1) of the doublet mentioned above. Fig. 4 shows the variation of S-1(T) with T for both the pH values. [The analysis of the 2D spectra did not yield a reliable estimate of S(T) for the higher frequency transition at 1,591 cm-1 at pH 6.2. (See SI Text.)] A fast spectral dynamics is observed at pH 6.2. On the contrary, for pH 8, the value of S-1 is practically constant for waiting times up to 3 ps. This result demonstrates a significant pH-induced change in conformation.

Fig. 4.

Inverse slope vs. T for M2TM G34* at pH 6.2 (blue circles) and pH 8 (black circles). The fit to the pH 6.2 data is shown in dashed lines.

Discussion

Identification of Protonated States of M2.

The results described above for M2TM in micelles indicate that there are significant changes in the vibrational spectrum and its dynamics as a result of the pH changing from ca. 6.2 to 8. The waiting time dependence of the 2D IR spectra indicates that the frequency of the vibrator is undergoing equilibrium fluctuations as exchange occurs between accessible equilibrium conformational states on the measured timescales (3). The SSNMR spectra, many of which are time averaged, also change with pH (25, 37, 39). The 2D IR spectrum gives information and dynamics on timescales as short as a few hundred femptoseconds, allowing one to probe configurations that would be averaged on the nanosecond to second NMR timescales. The frequency shifts of the IR spectral transitions depend on the electric field variations sensed in the spatial region of the vibrational mode. The vibrational frequency dynamics depend on the motions of associated charges such as those on water molecules and nearby charged side chains. The presence of multiple diagonal peaks and the absence of cross-peaks in the 2D IR spectra shows that the structures with different IR spectra are not exchanging much faster than ca. 10 ps.

Amide-I mode frequencies are very sensitive to the backbone structure and to tertiary interactions (38). For example, the frequency of a peptide amide-I vibration is downshifted from the gas phase value by ca. 60 cm-1 by the interactions with the protein backbone and partial charges on the side chains. The interactions with nearby water charges can also shift the transition to lower frequency by as much as ca. 10 cm-1 (41). According to the published structures of M2, the slight structural differences between the helices in the tetramer are such that each 13C = 18O edited amide transition would be expected to be composed of four approximately equal contributions. Deviations from this approximate symmetry must show up as increases in the amide-I mode transition bandwidth and shape over those expected for a typical isolated amide vibrator. Therefore, it is expected that each distinctive conformation of the tetramer, corresponding to one tetrad of Gly34 13C = 18O amide-I mode frequencies, will show one IR absorption band. The presence of more than one such conformation will broaden the IR bandwidth or cause a splitting into multiple transitions. That each amide-I mode for an isolated oscillator has a characteristic bandwidth and shape is based on experiments on transitions for many different proteins, peptides, and their isotopologues (3, 4, 7). Therefore, the observation of one amide-I band with the characteristic width and shape of an isolated amide group is strongly suggestive of there being one peak in the conformational distribution wherein all the glycines have the same frequency (backbone, side chain, and water distribution) within a small range. Such is the present case for M2 at high pH.

The 2D IR measurements show that there is a single species existing at high pH. The protonation of the four histidines of the M2 tetramer are strongly perturbed for functional reasons and occur with apparent pKa values of approximately 8.2 for the first two protonations, and 6.3 and < 5 in lipid bilayers for the third and the fourth (25, 42). Electrophysiological measurements show a similar activation pKa near eight and conduction pKa near six for full-length M2 (39, 43). The wild-type values are shifted upward by half a pKa unit by the D44N mutation. It follows that the state of the D24N, D44N variant studied here is likely predominantly +2 near pH 8, therefore the 2D IR shows that there is only one conformation associated with the +2 protonation state. This conclusion is based on the fact the bandwidth of the pH 8 transition is as expected of a single, conventional (i.e., approximately Gaussian, FWHM ∼15 cm-1) amide transition. At pH 6.2, the 2D IR transition of the pH 8 species decreases below detection (< 5%) and two new transitions, representing two different species having a signal ratio of 1.8∶1, appear at lower frequency. Because (i) the measurements are performed in equilibrated samples, (ii) the only protonatable side chains are the His37 residues, and (iii) the peaks change with the activity of hydrogen ions, it follows that both low-pH forms must represent a higher protonation state than observed at pH 8. Given the values of the third and fourth pKa for the tetramer, only a three protonated state should be present, suggesting that there are two conformations of His +3 present in an equilibrium population ratio of 2∶1. Each of these must present different environments to the carbonyl of G34. In an analogous situation, two different conformations of an α-helix in solution have been reported to show different IR spectra for the same 13C = 18O substitution (8). The two peaks observed are unlikely to correspond to perturbed Gly34 environments associated with a single tetrameric structure because the population ratio is neither of the predicted 1∶1 nor 3∶1 for such a scenario. Moreover, because the solvent rearrangements are fast, these environments cannot be two solvent structures, which would be clearly manifested in the 2D IR spectra as exchange peaks. The two conformations must exchange much more slowly than the experimental timescale. Thus the presence of two 2D IR transitions at low pH indicates that there are two distinct His + 3 conformations differing significantly in the environment near Gly34. Because we have not measured the degree of protonation of His37 for this peptide under the present experimental conditions, we will refer to the bands as the high-pH1585, low-pH1581, and low-pH1591 bands. A less likely possibility would be that the pH1585 form is neutral, and the low-pH1581 and low-pH1591 bands are +2 and +3, respectively. Finally, in the +3 state, various tautomeric forms of His37 lift the symmetry within the tetramer channel, and model calculations show that a splitting of the amide transitions may occur (SI Text). Such computations using the amide-I field maps of Skinner and coworkers (41) for the “open” His3+ crystal structure (see SI Text) involved analysis of vibrational frequency distributions for a τ and a π tautomer of the single neutral histidine. The computed frequencies indicate that the 32 amide transitions from the equally weighted eight tautomeric states show a double peaked distribution, providing one possible interpretation of the two low-pH transitions.

The pH Dependence of the Water Dynamics: Ebb and Flow at Gly34.

For an anharmonic oscillator, the decay of the inverse of the slope S(T) is a measure of the picosecond decay of the frequency–frequency correlation function (3, 40). Its decay tracks those frequency correlations that decay considerably slower than the inverse bandwidth of the IR transition. With increasing waiting time, the spectra become more upright (S≫1) as the initial inhomogeneous distribution undergoes spectral diffusion. The relative contribution to the spectra from homogeneous and inhomogeneous broadening components is also an important component of the slope dynamics with a purely homogeneous transition having an inverse slope of zero. The variations of the inverse slope with waiting time T between unity and zero is expected to measure the decay of the correlations between the coherence and detection time measurements of the vibrational frequency (44, 45).

The 2D IR spectral shape of the 1,581 cm-1 peak of M2 at pH 6.2 is distinctly dependent on the waiting time T as seen in Fig. 3, which indicates that the formal and partial charges that dominate the electric fields sensed by the Gly34 amide unit are mobile on the timescale of these experiments. To obtain a semiquantitative measure of these spectral dynamics, we plotted in Fig. 4 the T dependence of the inverse slopes of the 2D IR spectra.

The decay of the inverse slope is much faster for the low-pH1581 transition than for the high-pH form. It will be argued below that these results indicate a significant amount of mobile water has come within hydrogen bond range of the Gly34 carbonyl at low pH, whereas the pH1585 band does not reveal any water motions.

In Fig. 4, the pH 6 data are fitted (dashed lines) to a model frequency correlation function:

At T = 0, the model correlation is set at 0.74, implying that there is a homogeneous dephasing contribution. The 75-fs and 1.26-ps relaxation times are observed in the experiment because they are not motionally narrowed. The contribution from relaxation processes that are much longer than the times that are accessed in the experiments are also seen clearly in the slope measurements. The 1.25-ps decay for pH 6.2 is very similar to the H-bond making and breaking relaxation time observed for amides and small peptides in water (9). The faster component in the experiment, which is in reality an estimate, is typical of the contribution of small motions of charged side chains of the peptide backbone and librations of nearby water molecules which may or may not be directly bonded to the C = O of Gly34. At pH 8, the correlations decay much more slowly, with virtually no spectral dynamics occurring up to a waiting time of 3 ps. The pH dependence and the ultrafast relaxation arising from fluctuations of the water suggests that the number of water molecules in the channel has significantly increased at pH 6 compared with pH 8. Recent spin diffusion NMR results (37) indicate that residues between Val27 and Gly34 are more accessible to water at low pH than at high pH and that the water is less mobile (on a millisecond timescale) at high pH. These observations are consistent with the 2D IR results. The deduced pH dependent change in the properties of water near Gly34 gives some insight into the proton conducting properties of M2. A key factor in proton transport in TM channels is recognized to be solvation of the proton by the water embedded or confined in the channels (46). For M2 at low pH, the channel pore is sufficiently hydrated to stabilize a hydronium ion, whereas at high pH, the water density drops and we see that nuclear motions of any remaining water structure is frozen on the 10-ps timescale. Indeed the frequency relaxation of Gly34 in the His2+ state at pH 8 is slowed to longer than 10 ps and its Gly34 amide-I vibrational frequency is blue shifted from the pH1581 band. These dynamics imply that there is no bulk-like water near Gly34 at high pH, but that it is present in the activated low-pH form. Water molecules have been identified in diffraction (27) and SSNMR experiments (47). Such an immobilized structure of water may not allow the channel to undergo motions required for the diffusion of protons beyond His34 and Trp41, thereby preventing the flow of protons until the low-pH conformation is generated.

Conclusions

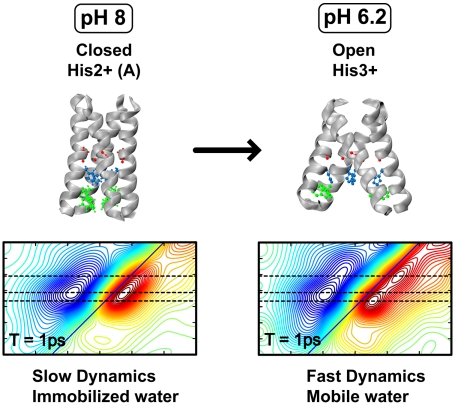

Summarizing, it has been shown that 2D spectroscopy uniquely reveals different structural properties of conformers of the M2 proton channel at ambient temperature and that the characteristics of the water in the channel is strongly pH dependent, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The Gly34 probe senses mobile bulk-like water at pH 6 but not at pH 8. The single conformer identified at pH 8 very likely corresponds to a resting state of the channel. In this state, Gly34 does not exhibit any sub-10-ps spectral dynamics, which suggests the absence of water that can participate in making and breaking of hydrogen bonds on a timescale comparable with liquid water. Any remaining water sensed by the Gly34 residue must be immobilized on the ca. 10-ps timescale. This finding, however, does not in any way contradict the possibility of a more rigid water structure, which could have a role in the transmission of protons to His37, particularly on the long timescale (millisecond) associated with proton transport through M2. Decreasing the pH to 6.2 leads to the formation of two new features, indicating that they represent different, more highly protonated species. The lower frequency oscillator (low pH1581) shows vibrational dynamics on a timescale of amide modes in aqueous solutions. These findings are in excellent agreement with previous SSNMR, MD, and crystallographic studies, which have shown expansion of the channel near the cellular interior and/or increased hydration at low pH. Both of these changes should facilitate the accommodation of more water molecules in the neighborhood of the Gly34. The occurrence of the fast vibrational dynamics confirms that water flows into an open state of the channel. Thus, the scenario that emerges is one in which the protein, when at low protonation level, lies in a relatively rigid state capable of binding one or more excess protons with high affinity. However, once the high-affinity sites are saturated and the +3 state is generated, the protein develops new conformations whose constituent pore water becomes more liquid, allowing diffusion past the gate-keeping His37/Trp41 pairs, and increases the rate of diffusion of the proton to the virus interior. Although we have focused on equilibrium measurements in this work, the electrical and chemical gradients experimentally encountered in proton conduction are generally modest (one to a few kBT), indicating that these same states and processes that are observed under equilibrium in spectroscopic studies are quite likely to hold for the vectoral proton transfer, as shown through the success of structure-based models for proton conduction through M2 (28, 43).

Fig. 5.

Functional model of M2 as revealed by 2D IR. The Protein Data Bank structures 2RLF and 3C9J were used to represent the closed and open states, respectively. The residues Gly34, His37, and Trp41 are shown in red, blue, and green, respectively.

Materials and Methods

Standard solid phase synthesis was used to make the modified M2TM peptide having sequence SSNPLVVAASIIGILHLILWILNRL. Fmoc-protected amino acids and rink amide resins were obtained from NovaBiochem. 13C-isotope labeled Glycine, H2O18 and D2O were bought from Cambridge Isotope. Fmoc-protected 13C18O-Gly was prepared with published procedures (48). The peptide was cleaved with TFA, purified with a Vydac prep column on Varian HPLC system, and its purity tested with a Vydac analytical column on an Agilent analytical HPLC system. Pure peptide was lyophilized and stored as dry powder. A fresh ethanol stock solution of the peptide was made before each experiment. Its concentration was determined by Trp absorbance. DPC was obtained from Avanti Lipids and prepared as an ethanol stock. Methanol-D4 was obtained from Isotec.

Sample Preparation.

Both peptide and DPC (for final concentrations of 10 mM peptide and 350 mM DPC) were dried from ethanol stocks with nitrogen flow. Methanol-D4 (100 uL) was added to the dried film, equilibrated for 30 min, and dried with nitrogen flow again. Residue solvent was removed by lyophilization for 3 h. A D2O buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate and 500 mM sodium chloride) was prepared fresh for each sample and used to solvate the dry film of peptide and DPC mixture. Three repeats of 30-s vortexing followed by 1-min bath sonication were used to reduce inhomogeneous aggregates. For each sample, a blank of DPC only was prepared using exactly the same methods: These samples provided baselines for the infrared experiments. Experiments were conducted at two pD values: 6.64 and 8.44. The corresponding pH values quoted in the text are 8 and 6.2, because pD = pH + 0.44 (49). All experiments were in D2O, often referred to as “water” in the paper. The amide-I mode is often referred to as amide-I’ when the N-H is deuterated as is the case here. Furthermore, it is known that the M2 channel conducts protons when the extracellular solvent is switched to D2O from H2O (30).

Two-Dimensional IR Spectroscopy.

The details of the 2D IR experimental scheme have been described elsewhere. In short, the sample is excited with a sequence of three infrared pulses at ca. 6 μm having wavevectors k1, k2, and k3; a fourth pulse, the local oscillator, heterodynes the signal, in the phase matched direction -k1 + k2 + k3, at a detector at the focal plane of a monochromater. All pulses had spectral bandwidth of approximately 200 cm-1 and were chosen to have the same electric polarization. The data were collected by varying the delay (τ) between the first two pulses from -2.75 to 3.25 ps in steps of 2 fs. A Fourier transform along τ yields the variation with ωτ and the final 2D spectrum consists of plots of ωτ, the “pump,” versus the monochromator frequency ωt, which acts as the “probe.”. All data were collected at 300 K.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation-Chemistry and the National Institutes of Health through Grants GM12592 and P41 RR01348 (to R.M.H.) and Grants AI74571 and GM56423 (to W.F.D.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103027108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de Groot BL, Grubmüller H. The dynamics and energetics of water permeation and proton exclusion in aquaporins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasaiah JC, Garde S, Hummer G. Water in nonpolar confinement: From nanotubes to proteins and beyond. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2008;59:713–740. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.59.032607.093815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YS, Liu L, Axelsen PH, Hochstrasser RM. 2D IR provides evidence for mobile water molecules in beta-amyloid fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17751–17756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909888106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganim Z, et al. Amide I two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:432–441. doi: 10.1021/ar700188n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YS, Liu L, Axelsen PH, Hochstrasser RM. Two-dimensional infrared spectra of isotopically diluted amyloid fibrils from A beta 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7720–7725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802993105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolano C, Helbing J, Kozinski M, Sander W, Hamm P. Watching hydrogen-bond dynamics in a beta-turn by transient two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy. Nature. 2006;444:469–472. doi: 10.1038/nature05352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang C, Senes A, Cristian L, DeGrado WF, Hochstrasser RM. Amide vibrations are delocalized across the hydrophobic interface of a transmembrane helix dimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16740–16745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608243103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backus EHG, et al. 2D-IR study of a photoswitchable isotope-labeled alpha-helix. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:3735–3740. doi: 10.1021/jp911849n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeCamp MF, et al. Amide I vibrational dynamics of N-methylacetamide in polar solvents: The role of electrostatic interactions. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:11016–11026. doi: 10.1021/jp050257p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YS, Wang J, Hochstrasser RM. Two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of the alanine dipeptide in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:7511–7521. doi: 10.1021/jp044989d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Hochstrasser RM. Characteristics of the two-dimensional infrared spectroscopy of helices from approximate simulations and analytic models. Chem Phys. 2004;297:195–219. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loparo JJ, Roberts ST, Tokmakoff A. Multidimensional infrared spectroscopy of water. I. Vibrational dynamics in two-dimensional IR line shapes. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194521.1–194521.13. doi: 10.1063/1.2382895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loparo JJ, Roberts ST, Tokmakoff A. Multidimensional infrared spectroscopy of water. II. Hydrogen bond switching dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:194522.1–194522.12. doi: 10.1063/1.2382896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fecko CJ, Eaves JD, Loparo JJ, Tokmakoff A, Geissler PL. Ultrafast hydrogen-bond dynamics in the infrared spectroscopy of water. Science. 2003;301:1698–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.1087251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinto LH, Lamb RA. The M2 proton channels of influenza A and B viruses. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8997–9000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Influenza virus proton channels. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5:629–632. doi: 10.1039/b517734k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salom D, Hill BR, Lear JD, DeGrado WF. pH-dependent tetramerization and amantadine binding of the transmembrane helix of M2 from the influenza A virus. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14160–14170. doi: 10.1021/bi001799u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duff KC, Ashley RH. The transmembrane domain of influenza-A M2 protein forms amantadine-sensitive proton channels in planar lipid bilayers. Virology. 1992;190:485–489. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91239-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinto LH, et al. A functionally defined model for the M-2 proton channel of influenza A virus suggests a mechanism for its ion selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11301–11306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong QF, Newns DM, Pattnaik P, Lear JD, Klein ML. Two possible conducting states of the influenza A virus M2 ion channel. FEBS Lett. 2000;473:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sansom MSP, Kerr ID, Smith GR, Son HS. The influenza A virus M2 channel: A molecular modeling and simulation study. Virology. 1997;233:163–173. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khurana E, et al. Molecular dynamics calculations suggest a conduction mechanism for the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1069–1074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811720106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeuchi H, Okada A, Miura T. Roles of the histidine and tryptophan side chains in the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:35–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manor J, et al. Gating mechanism of the influenza A M2 channel revealed by 1D and 2D IR spectroscopies. Structure. 2009;17:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu J, et al. Histidines, heart of the hydrogen ion channel from influenza A virus: Toward an understanding of conductance and proton selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6865–6870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601944103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stouffer AL, et al. Structural basis for the function and inhibition of an influenza virus proton channel. Nature. 2008;451:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya R, et al. Structure and mechanism of proton transport through the transmembrane tetrameric M2 protein bundle of the influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15075–15080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnell JR, Chou JJ. Structure and mechanism of the M2 proton channel of influenza A virus. Nature. 2008;451:591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature06531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smondyrev AM, Voth GA. Molecular dynamics simulation of proton transport through the influenza A virus M2 channel. Biophys J. 2002;83:1987–1996. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73960-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mould JA, et al. Mechanism for proton conduction of the M-2 ion channel of influenza A virus. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8592–8599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiorin G, Carnevale V, DeGrado WF. The flu’s proton escort. Science. 2010;330:456–458. doi: 10.1126/science.1197748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu FH, Luo WB, Hong M. Mechanisms of proton conduction and gating in influenza M2 proton channels from solid-state NMR. Science. 2010;330:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.1191714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma M, et al. Insight into the mechanism of the influenza A proton channel from a structure in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2010;330:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1191750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cady SD, Mishanina TV, Hong M. Structure of amantadine-bound M2 transmembrane peptide of influenza A in lipid bilayers from magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR: The role of ser31 in amantadine binding. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu J, et al. Backbone structure of the amantadine-blocked trans-membrane domain M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Biophys J. 2007;92:4335–4343. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi MG, Cross TA, Zhou HX. Conformational heterogeneity of the M2 proton channel and a structural model for channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906553106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo WB, Hong M. Conformational changes of an ion channel detected through water-protein interactions using solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2378–2384. doi: 10.1021/ja9096219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barth A, Zscherp C. What vibrations tell us about proteins. Q Rev Biophys. 2002;35:369–430. doi: 10.1017/s0033583502003815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balannik V, et al. Functional Studies and modeling of pore-lining residue mutants of the influenza A virus M2 ion channel. Biochemistry. 2010;49:696–708. doi: 10.1021/bi901799k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwac K, Cho MH. Molecular dynamics simulation study of N-methylacetamide in water. II. Two-dimensional infrared pump-probe spectra. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:2256–2263. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YS, Shorb JM, Mukherjee P, Zanni MT, Skinner JL. Empirical amide I vibrational frequency map: Application to 2D-IR line shapes for isotope-edited membrane peptide bundles. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:592–602. doi: 10.1021/jp807528q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma CL, et al. Identification of the functional core of the influenza A virus A/M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12283–12288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905726106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polishchuk AL, et al. A pH-dependent conformational ensemble mediates proton transport through the influenza A/M2 protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10061–10071. doi: 10.1021/bi101229m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwac K, Cho M. Two-color pump-probe spectroscopies of two- and three-level systems: 2-dimensional line shapes and solvation dynamics. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:5903–5912. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roberts ST, Loparo JJ, Tokmakoff A. Characterization of spectral diffusion from two-dimensional line shapes. J Chem Phys. 2006;125:084502.1–084502.8194521.13. doi: 10.1063/1.2232271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burykin A, Warshel A. What really prevents proton transport through aquaporin? Charge self-energy versus proton wire proposals. Biophys J. 2003;85:3696–3706. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74786-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cady SD, et al. Structure of the amantadine binding site of influenza M2 proton channels in lipid bilayers. Nature. 2010;463:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature08722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres J, Adams PD, Arkin IT. Use of a new label C-13 = O-18 in the determination of a structural model of phospholamban in a lipid bilayer. Spatial restraints resolve the ambiguity arising from interpretations of mutagenesis data. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:677–685. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krezel A, Bal W. A formula for correlating pK(a) values determined in D2O and H2O. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.