Abstract

Plasmid origins of replication are rare in bacterial chromosomes, except in multichromosome bacteria. The replication origin of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II (chrII) closely resembles iteron-bearing plasmid origins. Iterons are repeated initiator binding sites in plasmid origins and participate both in replication initiation and its control. The control is mediated primarily by coupling of iterons via the bound initiators (“handcuffing”), which causes steric hindrance to the origin. The control in chrII must be different, since the timing of its replication is cell cycle-specific, whereas in plasmids it is random. Here we show that chrII uses, in addition to iterons, another kind of initiator binding site, named 39-mers. The 39-mers confer stringent control by increasing handcuffing of iterons, presumably via initiator remodeling. Iterons, although potential inhibitors of replication themselves, restrain the 39-mer–mediated inhibition, possibly by direct coupling (“heterohandcuffing”). We propose that the presumptive transition of a plasmid to a chromosomal mode of control requires additional regulators to increase the stringency of control, and as will be discussed, to gain the capacity to modulate the effectiveness of the regulators at different stages of the cell cycle.

Keywords: replication control, DNA chaperone

Stable chromosome maintenance in proliferating cells requires restricting initiation of replication to once per cell cycle and to a specific stage of the cell cycle (1). This paradigm is not generally followed by bacterial plasmids, where the control system is meant for adjusting deviations from the mean. If cells are born with too many plasmid copies, then most copies do not replicate in that cell cycle. If cells are born with too few copies, some replicate more than once to regain the mean copy number. This process of adjustments spreads plasmid replication throughout the cell cycle. How the deviations are adjusted in bacterial chromosome replication remains largely unknown.

Bacteria usually have one chromosome, which must replicate in each cell cycle once and only once to avoid chromosome loss by underreplication and chromosome damage, which overreplication can cause (2). There seems to be some fundamental difference between the chromosome and plasmid replication controls because plasmids, although widespread in bacteria, are seldom found to drive chromosomal replication. Exceptions so far have been found in secondary chromosomes (those with fewer essential genes) of multichromosome bacteria (3).

Our knowledge of multiple chromosome maintenance in bacteria comes largely from studies of Vibrio cholerae (4). Of its two chromosomes, chromosome I (chrI) has many similarities to the Escherichia coli chromosome, including at the replication origin. The origin of the secondary chromosome (chrII) is similar to the well-studied iteron-bearing plasmid origins. However, unlike plasmids, chrII initiates replication at a specific time of the cell cycle, like other bacterial chromosomes (5–7). Here, we have studied control of chrII replication to understand how a plasmid-like replicon acquired the replication characteristics of a chromosome.

Iterons feature prominently in the origin of chrII (oriII) and outside of it, as they do in plasmids. Iterons are initiator binding sites and are required for replication initiation. They also exert negative control by two means: competition for initiator (titration) and handcuffing, which is coupling with each other via initiator bridges. Handcuffing appears to be the primary mechanism that restrains origin function (8). The iterons outside of the origin (present in a locus called inc) serve as negative regulators by increasing titration and by handcuffing with origin iterons. The extra iterons thus lower plasmid copy number.

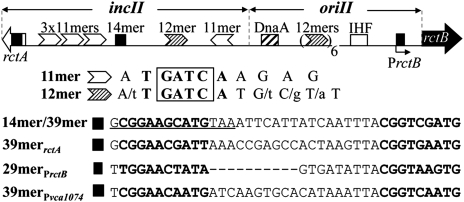

Whereas chrII and plasmids are similar in the origin, the inc locus of chrII (incII) is more complex (4). Within incII are five iterons (a 12-mer and four 11-mers), one 14-mer and a transcribed ORF (rctA) (9) (Fig. 1). These features are conserved in other Vibrio species. We have been studying these features for their likely role in revealing how the chrII system might have diverged from a simpler plasmid system (10).

Fig. 1.

A map of V. cholerae chrII region relevant to replication initiation. Also shown are sequences that bind RctB. Two genes, rctB (black arrow) and rctA (white arrow), flank the region. rctB encodes the chrII-specific replication initiator RctB, whereas rctA is transcribed only. PrctB and PrctA are promoters, both regulated by RctB (9, 11). oriII is the minimal region capable of autonomous replication in the presence of RctB in E. coli. incII controls oriII activity. Other than the binding sequences for DnaA and IHF, the rest of the elements are binding sites for RctB. The white and shaded arrowheads represent the iterons (11- and 12-mers with a guanine/adenine/thymine/cytosine (GATC) sequence). The black square in the middle of incII, originally called a 14-mer (the underlined sequence), is found here to be a part of a 39-mer, which can bind RctB; it consists of two direct repeats (shown in bold letters), linked by an AT-rich region. Also shown are three other 39-mer–like sites present in chrII, although in one case the AT-rich region was 9-bp, instead of 19-bp, long (29-merPrctB).

We have found the following: (i) Whereas plasmid initiators bind to iterons only, the chrII initiator binds in addition to a second kind of site, the 39-mers. One of the 39-mers includes the 14-mer, which by itself has no detectable function; (ii) the 39-mers are the key negative regulators of oriII. They function through iterons, primarily by promoting their handcuffing; and (iii) the iterons restrain the 39-mer, and thereby promote replication, whereas inc iterons of plasmids play only an inhibitory role. The chrII control system thus has evolved considerably from its apparent plasmid beginning. How the changes could make chrII replication more stringent and align the replication with the cell cycle will be discussed.

Results

A 39-mer Regulator of oriII.

The origin region of chrII is about 3 kb long and contains a negative control locus (incII, ∼0.6 kb), an origin (oriII, ∼0.4 kb), and the gene for the chrII-specific initiator (rctB, ∼2 kb) (Fig. 1). Except for the 14-mer locus of incII (defined as a regulatory sequence conserved among sequenced Vibrio genomes), other elements of incII appear to be binding sites of RctB (4, 9–11). The mechanism of the 14-mer function was unknown.

Here, we have studied the 14-mer function in E. coli. It was shown earlier that E. coli expressing RctB supports replication of plasmids with oriII as their sole origin (4). The surrogate host was chosen to avoid possible effects of the regulators on chromosome replication and growth of the native host. We used a three-plasmid system to study the 14-mer (10) (Fig. S1). One plasmid carried oriII, another supplied RctB at near physiological level (Fig. S2, lanes 1 and 4), and the third carried the elements of incII, including the 14-mer. In this assay system, the 14-mer did not change the copy number of the oriII plasmid (Fig. S1, fragment 1). However, a longer sequence, a 39-mer, which included 25 bp to the right of the 14-mer, reduced the copy number drastically, indicating that the sequence has the capacity to be a negative regulator (fragment 2). The 39-mer contains GC-rich direct repeats at its two ends with an AT-rich 19-bp intervening sequence. The repeats are conserved in other sequenced members of the Vibrio family (Fig. S3). The intervening sequence is not conserved but is AT rich in all cases. Both partial deletion and scrambling of repeat sequences compromised the activity (fragments 3–12, except 6). The length of the intervening DNA also appears important because an insertion of 5 or 10 bp, or a deletion of 5 bp, compromised the activity (fragments 13, 14, 15, and 17). In contrast, a deletion of 10 bp still retained about half the activity (fragments 16 and 18). Therefore, both the repeats and their relative positions are important for 39-mer function.

A homology search revealed three additional 39-mer–like sequences in chrII: one within rctA, one overlapping PrctB, and one upstream of vca1074 (Fig. 1). The first two sequences could be identified in other Vibrio family members (Fig. S3). All three sequences could lower oriII copy number (Fig. S1, last three fragments). Hereafter, the sequence originally found in the middle of incII will be called the 39-mer.

39-mer Binds RctB.

EMSA showed that the 39-mer binds RctB (10). Compared with the iterons, RctB bound to the 39-mer with a slightly higher affinity (Fig. S4). The binding caused both the sites to bend about 40°. Thus, the 39-mer, despite its distinct sequence and organization, is a binding site for RctB, and titration could be one mechanism of its function as a negative regulator.

Iterons and the 39-mer Titrate RctB.

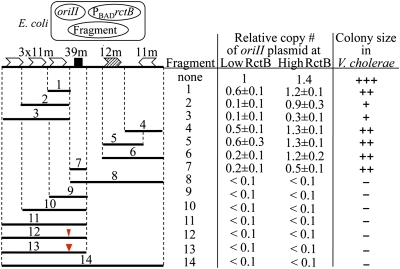

The three-plasmid system (Fig. S1) was used to compare the regulatory strength of different incII fragments. The 39-mer caused a greater reduction in the copy number of the oriII plasmid than single iterons (Fig. 2, fragments 1, 4, 5, and 7). The reduction was less when RctB supply was increased (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2). These results support initiator titration as a mechanism to inhibit replication by both kinds of sites because increasing the initiator could reverse the inhibition. When multiple binding sites were present in the incII fragment, the copy number decreased further, particularly when the 39-mer was included (e.g., fragments 8–14). The combined effect of the two kinds of sites was more than additive, suggesting that the sites cooperate to inhibit oriII (fragments 1 and 7 vs. 9). Moreover, inhibition by the 39-mer containing fragments was only poorly relieved by increased RctB production (fragments 7–14). This insensitivity implicated handcuffing in plasmid replication control (12, 13). The inhibitory activity of the two kinds of sites was maintained when their separation was increased by a half and a full turn of the DNA helix (fragments 12 and 13). The cooperation thus may not involve their direct physical contact. As discussed later, initiator remodeling upon 39-mer binding that promotes handcuffing best explains these results.

Fig. 2.

Regulatory activity of incII elements in trans. The incII activity was measured using a three-plasmid system in E. coli (Upper). One plasmid (pTVC35) carries oriII, as shown in Fig. 1. A second plasmid, PBAD-rctB plasmid (pTVC11), supplies RctB at low and high concentrations using arabinose at 0.002% and 0.2%, respectively. The low level approximated the physiological level of RctB (Fig. S2). The third plasmid (pTVC158 derivatives) supplied the fragments from the incII region, whose coordinates are shown. These were electroporated into E. coli BR8706 carrying the other two plasmids, and into V. cholerae CVC250. The last three columns show the oriII plasmid copy number in E. coli or the growth of V. cholerae cells in the presence of the incII fragments. Colony sizes of V. cholerae transformants were recorded as large (+++), medium (++), or small (+). In some cases no colonies were obtained (−). The narrow and wider red triangles in fragments 12 and 13 indicate 5- and 10-bp inserts, respectively.

The incII fragments were also tested in V. cholerae (Fig. 2, Right). The fragments that reduced oriII plasmid copy number in E. coli the most also reduced the growth of V. cholerae the most. The properties of chrII replication were also maintained faithfully in the surrogate host in earlier studies (10, 11, 14).

39-mer Activity Is Restrained by Iterons in cis.

In plasmids, decreasing the number of control (inc) iterons in cis or in trans to the origin always increased the plasmid copy number (15, 16). In contrast, the copy number of oriII plasmids decreased by deleting 3 × 11-mers in cis (10). To better understand the function of incII iterons, they were mutated by base substitution without altering their relative positions.

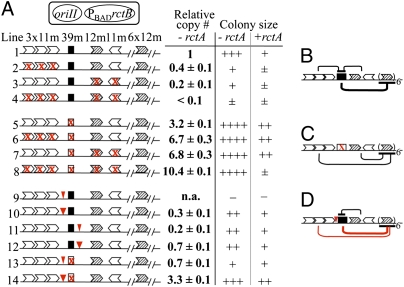

As before, the copy number of oriII plasmids decreased as more and more iterons were mutated, and was lowest when none of the iterons were intact (Fig. 3A, lines 1–4, and Fig. S5A). These results suggest that the 39-mer does not require the incII iterons to be active; on the contrary, its activity is restrained by the iterons (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Regulatory activity of incII elements in cis. (A) A two-plasmid system was used where one plasmid supplied the incII elements in cis to oriII and another (pTVC11) supplied RctB, using 0.2% arabinose. The oriII regions (with and without rctA) were cloned in a R6Kγ origin plasmid and the plasmids were maintained in CVC553. Plasmids in lines 1–14 carrying rctA were derivatives of pTVC210, and the corresponding plasmids lacking rctA were derivatives of pTVC211. Mutated sites are marked with red crosses, and 5- and 10-bp insertions as narrow and wider red triangles, respectively. The insertions were at chrII coordinate 444 in plasmids 9, 10, 13, and 14, and at coordinate 496 in plasmids 11 and 12. The plasmids were electroporated into BR8706/pTVC11, and colony sizes of the transformants were recorded as very large (++++) to barely growing (±). In some cases no colonies were obtained (−). The copy number of oriII plasmids was measured in the set without rctA, except for plasmid 9 (n.a., not applicable), where no transformants were obtained. The copy number of 1 is about 4× more than the chrII copy number (Experimental Procedures). (B –D) Models. The lines above the map of the oriII region show functional interactions among the incII elements, and the lines below, the interactions with origin iterons. Thicker lines signify stronger interaction, and red lines the interactions that are enhanced upon the 5-bp insertion. The models show the dual role of incII iterons as facilitators of replication by restraining the 39-mer and as inhibitors of replication by interaction with the origin (B). In the absence of 39-mer, iterons act only as inhibitors and additively (C). The 5-bp insertion changes the relative disposition of the three 11-mers so that they fail to interact with the 39-mer but become better disposed to inhibit the origin (D).

Mutating the 39-mer alone increased the copy number (Fig. 3A, lines 1 and 5), which indicates that even after restraint by the iterons, significant 39-mer activity remains, otherwise the copy number in line 5 should have been same or even lower than in line 1 (Fig. 3B). The copy number increased further as the iterons were mutated (lines 5–8), indicating that, as in plasmids, the iterons are potential inhibitors themselves (Fig. 3C).

Inversion of the 39-mer or its substitution with an iteron had the same effect as its inactivation (Fig. S5B, lines 5, 23, and 24, and lines 6, 25, and 26). The orientation-dependent activity of the 39-mer suggests that it interacts with other sites in cis. Inversion of the 39-mer possibly makes it more susceptible to restraint by the iterons (lines 1 and 3 vs. lines 24 and 26) and/or less susceptible to interaction with the origin (lines 27 and 31 vs. lines 30 and 34).

Cells transformed with oriII plasmids that included rctA exhibited reduced growth in all cases (Fig. 3A, –rctA vs. +rctA colony sizes). Because of the severity of the growth defect and frequent appearance of larger colony-forming revertants, copy number measurement proved futile or unreliable. In better growers, colony size and oriII plasmid copy number were correlated. The reduction of colony size when rctA was the only intact element of incII suggests that, like the 39-mer, rctA alone can be an effective negative regulator (Fig. 3A, line 8). The rctA activity could also be antagonized by iterons; the colony size increased upon their addition (lines 5 and 8). Most likely, a 39-mer is also responsible for the regulatory activity of rctA (39-merrctA; Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). In summary, rctA and the 39-mer are clearly the two most powerful negative regulators of oriII, and their activities are restrained by the incII iterons.

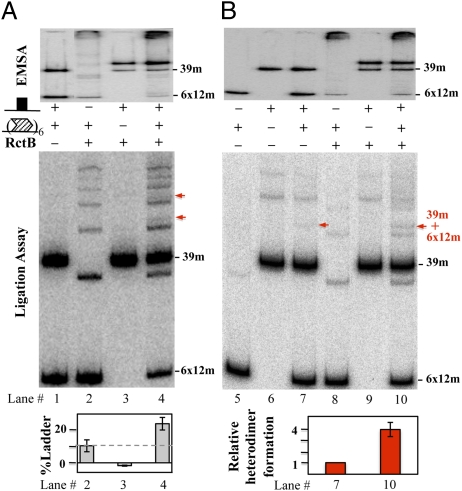

39-mer Enhances Handcuffing of Iterons.

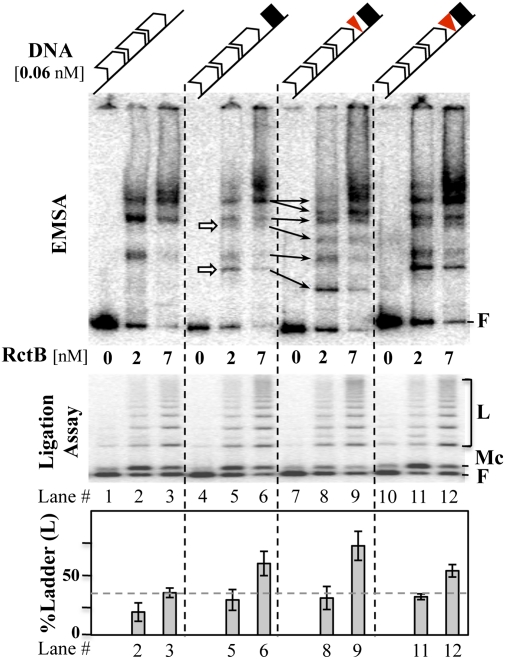

When the separation between the iterons and the 39-mer was increased by 5 bp, as opposed to 10 bp, the copy number of the oriII plasmid decreased significantly (Fig. 3A, lines 9–14). This phasing-dependent effect is usually taken as evidence for interactions between the sites flanking the insert (17, 18). Evidence for interactions between the 11- and 39-mers was sought initially by EMSA. In fragments carrying the 39-mer and the set of three 11-mers, new bands appeared, probably representing fragments where the 39-mer was bound to RctB (Fig. 4, arrows in lane 4 vs. 6). Insertion of 5 bp between the 11- and 39-mers increased the migration of all of the 39-mer bound species (arrows connecting lanes 7 and 9). Insertion of 10 bp made the migration similar to that of the fragment with no insert (lanes 5–7 vs. lanes 11–13).

Fig. 4.

EMSA and ligation assay with fragments carrying 3 × 11-mers and the 39-mer. (Upper) Fragments. The symbols are the same as in Fig. 3A. The fragments (Left to Right) were excised from pTVC-248, -255, -256, and 257, respectively, which added 100-bp vector DNA on both flanks. In EMSA (5% PAGE), the white arrows represent some of the new bands that appeared in 39-mer–carrying fragments. The other arrows connecting lanes 7 and 9 most likely represent identically bound species, but migrating differently because of the 5-bp insertion. (Lower) Ligated products of the binding reactions (1.2% agarose). Percent ladder [L, all bands above free (F) DNA and monomer circles (Mc)] was estimated for each lane as the intensity of L compared with the total intensity of DNA after subtracting the background ladder intensity without the initiator (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10). The gray dotted line in the bar diagram shows the level of ladder formation without the 39-mer (lane 3), so that the increase in the level due to the presence of 39-mer becomes more obvious. The error bars represent one SD and are derived from four different experiments.

Faster migration is usually attributed to relatively straight, as opposed to bent, DNA (19). Because all sites bend upon RctB binding, the 5-bp insert could have reduced overall bending of the complexes. The relatively straight structure of the complexes might thwart interactions between the two kinds of sites, favoring their interaction with the origin iterons and thereby more effective inactivation of the origin (Fig. 3D).

To determine whether the sites interact in vitro, ligase was added to the binding reactions. Handcuffing is indicated if the initiators increase the rate of formation of ligated products (12, 20). We expected that if the 5-bp insertion made the sites more open, their interactions in trans should be favored. In the presence of RctB, ladders of linear products increased in all iteron-carrying fragments, suggesting that RctB is capable of mediating handcuffing (Fig. 4). The ligated products, however, increased in all 39-mer carrying fragments, not just in the fragment with the 5-bp insert (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4 vs. 6–13).

A reason for this phasing-independent increase of ladder formation was suggested when it was found that the 39-mer does not handcuff with itself (Fig. 5, lane 1 vs. 3 and 6 vs. 9), and handcuffs weakly with iterons (Fig. 5, red arrows in lanes 4 and 10). The weak interaction was also seen in vivo (Fig. S6). If the 39-mer contributes so little to handcuffing directly, its contribution may be largely indirect (e.g., by remodeling the initiator to a handcuffing proficient form).

Fig. 5.

Effect of the 39-mer on handcuffing of origin iterons (6 × 12-mer) when the sites are in trans. (A) The 39-mer and 6 × 12-mer–containing fragments were used both at 0.03 nM and RctB at 7 nM. The fragments were excised from plasmids pTVC151 and pTVC228, which flanked the 39-mer with 300 bp and the 6 × 12-mer with 100 bp of vector DNA on both sides. The red arrows show the heteroligation products between the 6 × 12-mer and the 39-mer (lane 4). A 5% PAGE was used for both EMSA and the ligation assay. Percent ladder was estimated as in Fig. 4. (B) Same as A except that ladder formation by the 6 × 12-mer fragments was reduced by using twofold less DNA. The plot shows the intensity of the heteroligation product (red arrows) in lanes 7 and 10 (without and with RctB, respectively). The error bars representing one SD were derived from three different experiments.

To test for the latter possibility, the 39-mer and the iterons were used in separate fragments in the handcuffing reaction. The handcuffing of iterons was still enhanced (Fig. 5, lane 2 vs. 4 and 8 vs. 10). The increase in handcuffing, therefore, may not involve the 39-mer directly. It is also apparent that the interiteron (homo-) handcuffing dominates over 39-mer iteron (hetero-) handcuffing (Fig. 5, lane 4). When “homohandcuffing” was reduced by lowering iteron concentration, its level became comparable to the level of heterohandcuffing (Fig. 5, lane 10). The 39-mer also increased handcuffing of fragments with all of the origin iterons (Fig. S7A) or all of the control iterons (Fig. S7B).

In summary, our findings suggest that the 39-mer and the iterons influence activities of each other in three processes: RctB titration (Fig. 2), homohandcuffing, and heterohandcuffing (Figs. 3 and 5).

Discussion

In bacteria, the mechanisms that control chromosome and plasmid replication are generally different, which is also reflected in the organization of their origins. The paucity of plasmid origins in bacterial chromosomes and chromosomal origins in plasmids also suggest that some basic difference in the requirements of the two replication systems has selected against exchange of origins. This is surprising in view of the rampant horizontal gene transfer that has shaped bacterial genome evolution, and the fact that under laboratory conditions integrated plasmid origins can drive chromosomal replication (integrative suppression), and chromosomal origins can function in a plasmid (oriC minichromosomes). It should be noted that whether integrated or not, each origin retains its character and does not behave like the other in the ectopic context.

Plasmids and chromosomes differ in two respects from the perspective of replication control: Chromosomes are maintained usually in one to two copies, whereas plasmid copy numbers are usually higher, suggesting that the chromosomal control is more stringent. The chromosomal origins fire at a particular time of the cell cycle rather than at random times, which is characteristic of plasmid origins (7). A natural example of a plasmid-like origin in V. cholerae chrII provided an opportunity to understand how a typical plasmid origin could serve in chromosomal replication (3). We find that despite the similarity in the origins, the replication control system of the two has diverged significantly.

The basic mechanisms of plasmid copy number control are initiator autoregulation, initiator titration, and handcuffing. The chrII replication control system has retained all three, but has extra features. (i) The iterons have a built-in Dam methylation site, and its full methylation is required for binding the chrII-specific initiator RctB (21). Because of methylation, the chrII iterons are subjected to sequestration by SeqA, which binds to hemimethylated sister origins following replication (21). During the sequestration period of the cell cycle, the iterons cannot bind RctB. (ii) The presence of methylation-independent binding sites, the 39-mers, in three locations (Fig. 1). (iii) The 39-mers, not the iterons, are the key inhibitors; they appear to remodel RctB, which increases handcuffing of iterons, thus enhancing the stringency of control. (iv) The iterons partially restrain the inhibitory activity of 39-mers. Having a powerful inhibitor and also a mechanism to restrain it make sense in the context of the cell cycle, as discussed below.

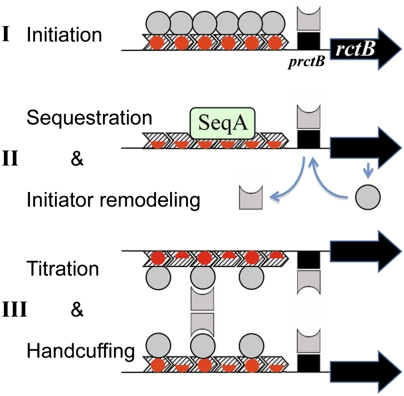

ChrII Replication in the Cell Cycle.

We speculate that the sequence of events of chrII replication cycle is as follows (Fig. 6). (i) Initiation occurs when the origin iterons are fully methylated and saturated with initiators. At that stage, the incII iterons restrain the 39-mers maximally to help initiation (Fig. 3B). (ii) Upon initiation, the origin iterons are hemimethylated and sequestered, which prevents their full methylation and binding to RctB. The hemimethylation period covers more than half the cell cycle. During this period, the 39-mers are the only sites that can bind RctB and remodel them, making the remodeled form a significant fraction of the initiator. (iii) When the sister origins come out of sequestration, they compete for RctB binding (titration) and get handcuffed efficiently due to the abundance of remodeled RctB. The capacity of 39-mers to remodel the initiator apparently plateaus due to competition from the iterons for initiator binding. In this scenario, initiation in the next cell cycle awaits the level of newly synthesized RctB, not remodeled by 39-mers, to become high enough to compete away the handcuffs. Apparently, the transition from plasmid-like to cell cycle-specific replication of chrII required both methylation-dependent and methylation-independent sites so as to allow initiation at one point of the cell cycle but switch off initiation in other times: The 39-mers dominate during the switch-off period, and the iterons during the switch-on.

Fig. 6.

A model of chrII replication cycle. For simplicity, the incII region is omitted from the diagrams. (I, Top) Initiation requires RctB initiators (circles) to saturate the origin iterons. The iterons bind only when they are fully methylated (marked by red circles). RctB changes form (circle to square with one semicircular edge) when it serves as an autorepressor by binding to a 39-mer–like sequence (black rectangle). (II, Middle) Iterons get hemimethylated (marked by red semicircles) following initiation, and become substrates for SeqA binding. The 39-mer remains binding competent and maintains autorepression throughout the cell cycle. The basal level of synthesis accumulates RctB in the remodeled form due to interactions from the three 39-mers of the origin region. (III, Bottom) As the iterons become fully methylated, they regain RctB binding proficiency. Initiation is prevented by distribution of the initiators to the two sister origins, so that none can be saturated (titration), and handcuffing of the sister origins. The handcuffing is mediated proficiently by the remodeled RctB, which serves as a bridging molecule. The tetrameric protein bridge is invoked because this is believed to be the case in handcuffing of plasmids (8). The RctB-bound iterons and 39-mers also handcuff directly (heterohandcuffing; Fig. 5). Later in the cell cycle, unmodified RctB dominates and eventually saturates the origin, causing initiation to ensue. In this model, the change in proportion of two forms of the initiator at different stages of the cell cycle is central to the replication switch.

Initiator Autorepression.

RctB is limiting for chrII replication (11, 14) (Fig. 2), and autorepression limits its synthesis. Iterons serve as operators for autorepression in plasmids. In chrII, a 39-mer–like sequence overlapping the rctB promoter (29-merPrctB; Figs. 1 and 6) is the likely operator. The site binds RctB in vivo (Fig. S1), and without a GATC in the sequence, it is expected to remain binding competent throughout the cell cycle. The autorepression is maintained in dam mutant cells (11). If the iterons were the operators in chrII, the promoter would be fully on during the long hemimethylation period. Involvement of methylation appears to have necessitated an operator to allow restraint of RctB throughout the cell cycle. The autorepression is, however, leaky. The basal level of synthesis apparently allows accumulation of the two forms of the protein at different stages of the cell cycle (Fig. 6).

Arguments for Initiator Remodeling.

An intriguing feature of the 39-mer is its ability to enhance handcuffing of iterons (Figs. 4 and 5 and Fig. S7). The 39-mer most likely acts as a DNA chaperone that remodels RctB to a form that enhances protein–protein interactions involved in handcuffing. Protein remodeling upon interaction with DNA is well known (22–24). It has been shown also for the two initiators of the iteron-bearing plasmids (23, 25) and for the E. coli initiator (26). Increased handcuffing could explain the potency of 39-mer–carrying fragments in reducing oriII copy number (Fig. 2, fragments 8–14). Inserts of 5 and 10 bp next to the 39-mer in these experiments were inconsequential, which is consistent with the remodeling hypothesis (Fig. 2, lines 12 and 13). RctB also needs remodeling by molecular chaperones to bind efficiently to both iterons and 39-mers (Figs. 2–5 and Figs. S4, S5, and S7) (10).

Restraint of 39-mer Activity by Iterons.

A major finding of this study is that the 39-mers are the key negative regulators of chrII replication. A single 39-mer could suppress oriII firing almost completely (Fig. 3, line 8 vs. 4). In contrast, the five iterons of incII could drop the copy number only about threefold (Fig. 3, line 8 vs. 5). The level of inhibition is apparently excessive, requiring their restraint by iterons. The restraint could be by direct coupling of the 39-mer with incII iterons (heterohandcuffing; Fig. 5 and Fig. S6). Direct interaction is also likely because inversion of the 39-mer made the site less effective (Fig. S5, line 27 vs. 30 and 31 vs. 34), and insertion of 5 bp made it more effective (Fig. 3, lines 9–14). It is important to note that the 39-mer and rctA remain effective inhibitors despite iteron-mediated restraint.

ChrII Provides a Unique Example of Replication Control.

E. coli aside, chromosome replication has been studied in detail in Bacillus subtilis and Caulobacter crescentus (27). The negative control mechanisms differ in these bacteria. Here, we find in chrII of V. cholerae yet another mode of replication control. ChrII thus provides a unique handle to understand once-per-cell-cycle replication initiation. An understanding in chrII is likely to benefit understanding of similar chromosomes in other members of the Vibrio family and how multiple chromosomes are maintained in bacteria.

Experimental Procedures

Strains and Plasmids.

V. cholerae and E. coli strains, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2. oriII fragments were amplified from N16961 (CVC205) DNA by PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity polymerase (New England Biolabs). In some cases, short fragments were obtained by annealing complementary oligonucleotides (10).

For Fig. 2, PCR-derived fragments (except for fragment 7, which was made of oligonucleotides) were cloned as in Fig. S1, and the cloned fragments were subsequently transferred to a lower copy-number vector, pTVC158, to reduce incompatibility. The resulting plasmids carrying fragments 1–14 were pTVC-179, -178, -94, -154, -153, -96, -202, -98, -177, -176, -175, -360, -361, and -155, respectively. For plasmids used in Fig. 3A and Fig. S5, to maintain and confirm orientations of all cloned fragments, a promoterless lacZ gene as a SmaI/DraI fragment was positioned downstream of the PrctB promoter in pTVC20 (10). The resulting plasmid, pTVC210 (line 1 with rctA in Fig. 3A), was used to construct all other mutant plasmids. These were created by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis (28). The mutations were as follows: 5-bp insertion (5′-TACTG-3′), 10-bp insertion (5′-TACTGATGAT-3′), substitution of the first direct repeat with a 12-mer (5′-CGGAAGCATG-3′ to 5′-ATGATCATGCTT-3′), inactivation of the repeat (5′-CGGAAGCATG-3′ to 5′-GCCTTCGTAC-3′), and inactivation of methylation site in 11- and 12-mers (5′-GATC-3′ to 5′-ctaC-3′, except for the 11-mer next to the 39-mer, where the change was to 5′-GtaC-3′). The PCR products were digested with KpnI, and the mutated oriII fragments were used to replace the KpnI fragment of pTVC210. In Fig. S5B, the plasmids had the incII locus variously deleted: Starting from left, the deletions covered rctA only (line 1, pTVC211), up to 3 × 11-mers (line 27, pTVC251), up to the 39-mer (line 35, pTVC253), and the entire locus (line 39, pTVC337). Mutant derivatives of these plasmids were obtained by exchanging the KpnI fragment of WT oriII of pTVC210 with PCR-derived mutant KpnI fragments. All plasmids carried the R6Kγ origin and were maintained in DH5Δlac(λpir) to supply the cognate initiator, π. The plasmids carrying rctA in lines 1–14 of Fig. 3A were pTVC-210, -436, -308, -437, -240, -439, -326, -438, -214, -226, -249, -268, -244, and -440, respectively. The corresponding plasmids lacking rctA were pTVC-211, -441, -318, -442, -247, -444, -335, -443, -246, -355, -299, -356, -389, and -454, respectively.

Plasmid Copy Number Measurements.

E. coli (BR8706), where araE is expressed constitutively from the chromosome, was used as a plasmid host. In Fig. 2 and Fig. S1, the cells were transformed with pTVC11 and pTVC35, maintaining 0.2% arabinose both before and after transformation to ensure RctB supply. The cells were then transformed with incII-bearing plasmids. After overnight growth under selection, the colonies were collected by washing the plates, and the OD600 of the cell suspension was measured. This was necessary because in many instances the transformants showed heterogeneous colony sizes when overgrown or did not grow in liquid culture. For experiments of Fig. 3 and Fig. S5, the procedure was the same except that the cells had only pTVC11, and they were then transformed with oriII plasmids. The plasmid copy number was determined as described (20). In Fig. 3, the copy number of the starting plasmid (called 1, line 1) approximates within 10% the copy number of attP1 locus of the E. coli chromosome at 66.5′, determined using a miniP1 plasmid pSP102 as an internal standard (29). In Fig. 2 and Fig. S1, the copy number of 1 is 8× more. Under this growth condition, E. coli maintains four to eight chromosomes, and V. cholerae one to two copies of chrII (30).

EMSA and Ligation Assays.

Assays were performed exactly as described (10, 20), except for preparation of the fragments. The fragments of Fig. S4 were prepared from pBEND2, whereas those of Figs. 4 and 5 and Fig. S7 were prepared from derivatives of pTVC61/pTVC243. pTVC243 derivatives (5 μg) were cut by HpaI and EcoRV, the ends dephosphorylated using shrimp alkaline phosphatase, and the fragments with oriII were gel purified. A total of 1–5 pmol of ends were labeled in 50 μL of 1X T4 kinase buffer (New England Biolabs) with 8.5 pmol [γ-32P] ATP (50 μCi/reaction; Perkin-Elmer) using 30 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase for 30 min at 37 °C. The enzyme was inactivated for 15 min at 65 °C, and the fragments were purified using Sephadex G-50 column (0.8-mL bed volume; Roche Diagnostics). The amount of labeled DNA was determined by TCA precipitation using salmon sperm DNA (20 μg; Invitrogen) as a carrier.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our colleagues Michael Yarmolinsky, Michael Lichten, and Yikang Rong, and one of the reviewers for suggestions to improve the manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Center for Cancer Research of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1013244108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nielsen O, Løbner-Olesen A. Once in a lifetime: Strategies for preventing re-replication in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:151–156. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simmons LA, Breier AM, Cozzarelli NR, Kaguni JM. Hyperinitiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli leads to replication fork collapse and inviability. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:349–358. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan ES, Fogel MA, Waldor MK. Divided genomes: Negotiating the cell cycle in prokaryotes with multiple chromosomes. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1129–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egan ES, Waldor MK. Distinct replication requirements for the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Cell. 2003;114:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00611-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan ES, Løbner-Olesen A, Waldor MK. Synchronous replication initiation of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R501–R502. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen T, Jensen RB, Skovgaard O. The two chromosomes of Vibrio cholerae are initiated at different time points in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 2007;26:3124–3131. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard AC, Helmstetter CE. Replication patterns of multiple plasmids coexisting in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1380–1383. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1380-1383.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulsson J, Chattoraj DK. Origin inactivation in bacterial DNA replication control. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan ES, Duigou S, Waldor MK. Autorepression of RctB, an initiator of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II replication. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:789–793. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.789-793.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkova-Canova T, Srivastava P, Chattoraj DK. Transcriptional inactivation of a regulatory site for replication of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12051–12056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605120103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal D, Venkova-Canova T, Srivastava P, Chattoraj DK. Multipartite regulation of rctB, the replication initiator gene of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7167–7175. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7167-7175.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEachern MJ, Bott MA, Tooker PA, Helinski DR. Negative control of plasmid R6K replication: Possible role of intermolecular coupling of replication origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7942–7946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pal SK, Chattoraj DK. P1 plasmid replication: Initiator sequestration is inadequate to explain control by initiator-binding sites. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3554–3560. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.8.3554-3560.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duigou S, et al. Independent control of replication initiation of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes by DnaA and RctB. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6419–6424. doi: 10.1128/JB.00565-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chattoraj D, Cordes K, Abeles A. Plasmid P1 replication: Negative control by repeated DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6456–6460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abeles AL, Reaves LD, Youngren-Grimes B, Austin SJ. Control of P1 plasmid replication by iterons. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochschild A, Ptashne M. Cooperative binding of lambda repressors to sites separated by integral turns of the DNA helix. Cell. 1986;44:681–687. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miron A, Mukherjee S, Bastia D. Activation of distant replication origins in vivo by DNA looping as revealed by a novel mutant form of an initiator protein defective in cooperativity at a distance. EMBO J. 1992;11:1205–1216. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Zwieb C, Wu C, Adhya S. Bending of DNA by gene-regulatory proteins: Construction and use of a DNA bending vector. Gene. 1989;85:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90459-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das N, Chattoraj DK. Origin pairing (‘handcuffing’) and unpairing in the control of P1 plasmid replication. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:836–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demarre G, Chattoraj DK. DNA adenine methylation is required to replicate both Vibrio cholerae chromosomes once per cell cycle. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruusala T, Crothers DM. Sliding and intermolecular transfer of the lac repressor: Kinetic perturbation of a reaction intermediate by a distant DNA sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4903–4907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Díaz-López T, et al. Structural changes in RepA, a plasmid replication initiator, upon binding to origin DNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18606–18616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Pino A, et al. Allostery and intrinsic disorder mediate transcription regulation by conditional cooperativity. Cell. 2010;142:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abhyankar MM, Reddy JM, Sharma R, Büllesbach E, Bastia D. Biochemical investigations of control of replication initiation of plasmid R6K. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6711–6719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujimitsu K, Senriuchi T, Katayama T. Specific genomic sequences of E. coli promote replicational initiation by directly reactivating ADP-DnaA. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1221–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.1775809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katayama T, Ozaki S, Keyamura K, Fujimitsu K. Regulation of the replication cycle: Conserved and diverse regulatory systems for DnaA and oriC. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:163–170. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito W, Ishiguro H, Kurosawa Y. A general method for introducing a series of mutations into cloned DNA using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1991;102:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90539-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pal SK, Mason RJ, Chattoraj DK. P1 plasmid replication. Role of initiator titration in copy number control. J Mol Biol. 1986;192:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava P, Chattoraj DK. Selective chromosome amplification in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:1016–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.