Abstract

The ability of directionally selective (DS) retinal ganglion cells to respond selectively to stimulus motion in one direction is a classic unresolved example of computation in a local neural circuit. Recent evidence indicates that DS responses occur first in the retina in the dendrites of starburst amacrine cells (interneurons presynaptic to the ganglion cells). We report that the directional responses of starburst-cell dendrites and DS ganglion cells are highly sensitive to the polarity of the transmembrane chloride gradient. Reducing the transmembrane chloride gradient by ion substitution or by blocking the K–Cl cotransporter resulted in the starburst cells responding equally to light moving in opposite directions. Conversely, increasing the chloride gradient by blocking the Na–K–Cl cotransporter eliminated responses to light moving in either direction. Moreover, in each case, blocking the chloride cotransporters or reducing the transmembrane chloride gradient eliminated the directional responses of DS ganglion cells in a manner opposite that of the starburst cells. These results indicate that chloride cotransporters play a key role in the generation of direction selectivity and that the directional responses of starburst cells and DS ganglion cells are exquisitely sensitive to the chloride equilibrium potential. The findings further suggest that the directional responses of DS ganglion cells are mediated in part by the directional release of γ-aminobutyric acid from starburst dendrites and that the asymmetric distribution of the two cotransporters along starburst-cell dendrites mediates direction selectivity. A model of direction selectivity in the retina that incorporates these and other findings is discussed.

Neural coding of the direction of image motion occurs in the vertebrate visual system in a type of retinal ganglion cell. Directionally selective (DS) ganglion cells respond strongly to stimulus motion in one (preferred) direction, but they respond little or not at all to motion in the opposite (null) direction. Although DS ganglion cells were first described almost four decades ago (1), the cellular mechanisms that underlie the phenomenon are still largely unknown. In the rabbit retina, there are two distinct types of DS ganglion cell that give either ON–OFF or ON–center responses to stationary flashing illumination. Pharmacological studies indicate that the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediates null direction inhibition of ON–OFF rabbit DS ganglion cells by activation of GABA type A (GABAA) receptors (2, 3). Starburst amacrine cells (SACs) are an essential component of the mechanism that generates direction selectivity because selective elimination of this cell type eliminates the directional light responses of ON–OFF DS ganglion cells (4) and because the dendrites of SACs generate directional light responses (5, 6).

Activation of GABAA and GABA type C (GABAC) receptors opens chloride channels. In the retina and elsewhere in the CNS, two types of cation–chloride cotransporter, the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters, have been identified (7, 8). These cotransporters are the primary means by which the intracellular chloride concentration is regulated. The K–Cl cotransporter extrudes chloride from neurons, whereas the Na–K–Cl cotransporter transports chloride into cells. GABA hyperpolarizes neurons when the chloride equilibrium potential (ECl) is more negative than the resting membrane potential because of the action of the K–Cl cotransporter (7, 9). In contrast, GABA depolarizes neurons when the ECl is more positive than the resting membrane potential because of the action of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter (9). Thus, depending on the activity of chloride cotransporters in a retinal neuron, GABA will either hyperpolarize or depolarize the cell.

We report here that blockade or inhibition of chloride cotransporters or reducing the transmembrane chloride gradient eliminates direction selectivity in SACs and DS ganglion cells, indicating that chloride cotransporters mediate direction selectivity and that direction selectivity is highly sensitive to the chloride gradient. In addition, we demonstrate that the dendrites of SACs respond selectively to stimulus movement away from their somata, compared with stimulus movement toward their somata, and that this response difference is eliminated by (i) blockade of chloride cotransporters and (ii) a small reduction in the transmembrane chloride gradient. Our results suggest that the directional release of GABA from SAC dendrites mediates in part the directional responses of DS ganglion cells. Finally, a model of direction selectivity that incorporates these and other findings is proposed.

Materials and Methods

Experiments were performed on superfused retinal eyecups obtained from pigmented and New Zealand White rabbits ≈2.5 kg in weight, as described (10). Briefly, rabbits were deeply anesthetized by i.p. injection with urethane (1.5 g/kg), and an eye was enucleated after additional local intraorbital injections of 2% Xylocaine. Deeply anesthetized rabbits were killed by injection of 4 M KCl into the heart. The care and use of rabbits followed all federal and institutional guidelines. In most of the experiments, Ames medium, including organics and amino acids but excluding horse serum, was used. In the chloride substitution and patch-clamp experiments, however, the control superfusate contained 117.0 mM NaCl, 3.1 mM KCl, 10.0 mM glucose, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 30.0 mM Na HCO3, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, and 0.1 mM l-glutamate. The filling solution of the patch-clamp pipettes contained 14.0 mM KCl, 100.0 mM K-gluconate, 5.0 mM EGTA, 5.0 mM Hepes, 3.0 mM MgATP, 0.5 mM Na3GTP, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 20.0 mM Na2Pcr, and 4.1 mM NaHCO3. All chemicals and test drugs were purchased from Sigma. Extracellular recordings of single ON–OFF DS ganglion cells from pigmented rabbits and extracellular and whole-cell patch clamp recordings of displaced SACs from New Zealand White rabbits were obtained by using standard techniques. All statistical comparisons were made by using Student's unpaired t test.

SACs were labeled by intraocular injection of 0.3 μg of 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, made under xylazine–ketamine anesthesia 1 day before each experiment (11, 12). Displaced SACs were identified by the small diameter of their somata (≈10 μm) and by their preferential labeling with the fluorescent dye 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, as seen during brief fluorescence illumination. When SACs were identified, microelectrode manipulation was achieved by using infrared illumination. The identity of SACs was confirmed in some cases by injection of biocytin tracer.

Results

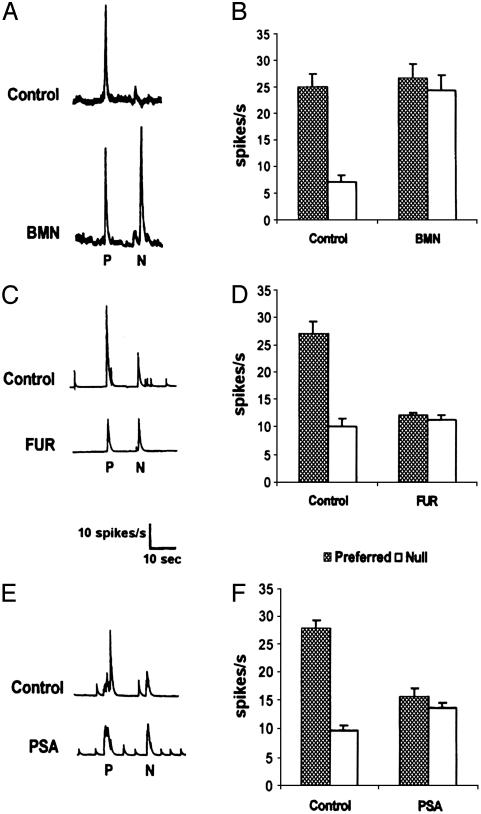

The effects of the loop diuretics, bumetanide (BMN) and furosemide (FUR), were studied to determine whether the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters mediate direction selectivity. At low micromolar concentrations (e.g., 10 μM), BMN is a selective blocker of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter (9). At low micromolar concentrations (e.g., 25 μM), FUR is a selective blocker of the K–Cl cotransporter (7, 9). Superfusion of BMN (10–200 μM) eliminated the directional responses of ON–OFF DS ganglion cells by increasing the response to stimulus movement in the null direction. A representative example of the effect of 10 μM BMN (Fig. 1A) and the averaged effect of BMN (Fig. 1B) are shown. Superfusion of 10 μM and 200 μM BMN had similar effects on the directional responses of the DS cells, except that the lower concentration took ≈10 times longer to achieve its effect (20 min vs. 2 min). In contrast, FUR (25–50 μM) also eliminated directional selectivity, but it did so by decreasing the response to stimulus movement in the preferred direction. A representative example (Fig. 1C) and averaged effect (Fig. 1D) of FUR are shown.

Fig. 1.

Blockade of chloride cotransport or reduction of transmembrane chloride gradient eliminates the directional responses of rabbit ON–OFF DS ganglion cells. (A) Application of 10 μM BMN eliminated direction selectivity by increasing the response to stimulus movement in the null (N) direction. (B) Average responses to stimuli moving in preferred (P) and null directions before and after BMN application demonstrate that the average response size to stimuli moving in the null direction was significantly greater during BMN application (P < 0.01; n = 10). (C) Application of 25 μM FUR eliminated direction selectivity by decreasing the response to stimulus movement in the preferred direction. (D) Average responses to stimuli moving in preferred and null directions before and after FUR application illustrate that the average response size to stimuli moving in the preferred direction was significantly smaller during FUR application (P < 0.01; n = 6). (E) Reducing the transmembrane chloride gradient by replacing 15 mM Cl- with PSA, an anion that does not flow through Cl- channels, eliminated direction selectivity by decreasing the response to stimulus movement in the preferred direction. (F) Average responses to stimuli moving in preferred and null directions before and after PSA substitution illustrate that the average response size to stimuli moving in the preferred direction was significantly smaller during PSA substitution (P < 0.01; n = 6). Spike activity of single ganglion cells to slits of light (1.0 × 0.3 mm) moving at 1.2 mm/s is shown as spikes per second (A, C, and E). Responses to a single movement of the slit stimulus in the preferred and null directions before and after test drug applications are shown.

If chloride cotransporters mediate direction selectivity, then the directional responses of DS ganglion cells should depend on the transmembrane chloride gradient. We tested this hypothesis by substituting 15 mM Cl- in Ringer's solution with 15 mM pentanesulfonic acid (PSA), an anion that does not traverse Cl- channels. This small reduction in the chloride gradient eliminated direction selectivity by decreasing the response to stimulus movement in the preferred direction (Fig. 1E), an effect similar to that of FUR (Figs. 1 C and D). The averaged effect of PSA is shown in Fig. 1F.

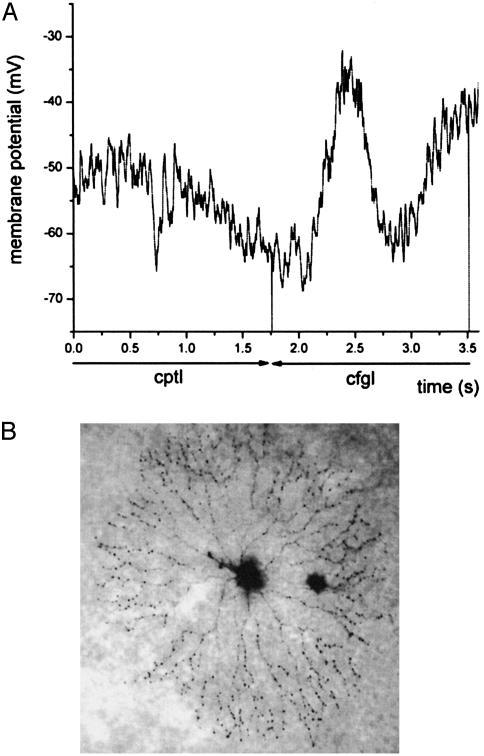

Chloride cotransporters and the transmembrane chloride gradient also mediate the directional responses of displaced SACs to moving stimuli. We found that SAC dendrites exhibited directional light responses, as reported (5, 6), That is, the SACs depolarized and generated spikes to slit stimuli that moved centrifugally from their somata to the periphery, but the cells hyperpolarized and did not spike to stimuli that moved centripetally from the periphery to their somata (Figs. 2 and 3). Fig. 2 A illustrates the typical directional light responses of SACs recorded under whole-cell current-clamp mode. Fig. 2B illustrates a representative example of a SAC that generated directional responses after filling with biocytin. Fig. 3 illustrates that displaced SACs, which have been reported to spike in response to visual stimuli and depolarizing current injections (12–14; see refs. 15 and 16), generated directional spiking consistently when their light responses were recorded extracellularly. Although we did not observe light-evoked spiking when recording SACs in current clamp mode, depolarizing current injections consistently evoked spikes that were ≈20 mV in amplitude (data not shown). The failure to observe light-evoked action potentials under whole-cell current clamp mode is likely due to the disruption of the intracellular milieu.

Fig. 2.

SAC dendrites exhibit DS light responses. (A) SACs recorded under whole-cell current-clamp mode depolarized (mean = 8.9 ± 0.6 mV; n = 27) when slit stimuli moved centrifugally (cfgl) from their somata to the periphery and hyperpolarized (mean = -11.3 ± 1.0 mV; n = 27) when slit stimuli moved centripetally (cptl) from the periphery to their somata, indicating that the dendrites of SACs generate DS light responses. When whole-cell recording commenced, the average resting potential of the cells was -51.0 ± 1.2 mV (n = 27). (B) Representative example of a SAC that generated directional responses illustrated after filling with biocytin tracer. Slits of light (0.5 × 0.03 mm) were moved at 0.5 mm/s in the centripetal and centrifugal directions without stopping (see also Figs. 3 and 4). Responses to a single movement of the slit stimulus in the centrifugal and centripetal directions are shown (see also Figs. 3 and 4).

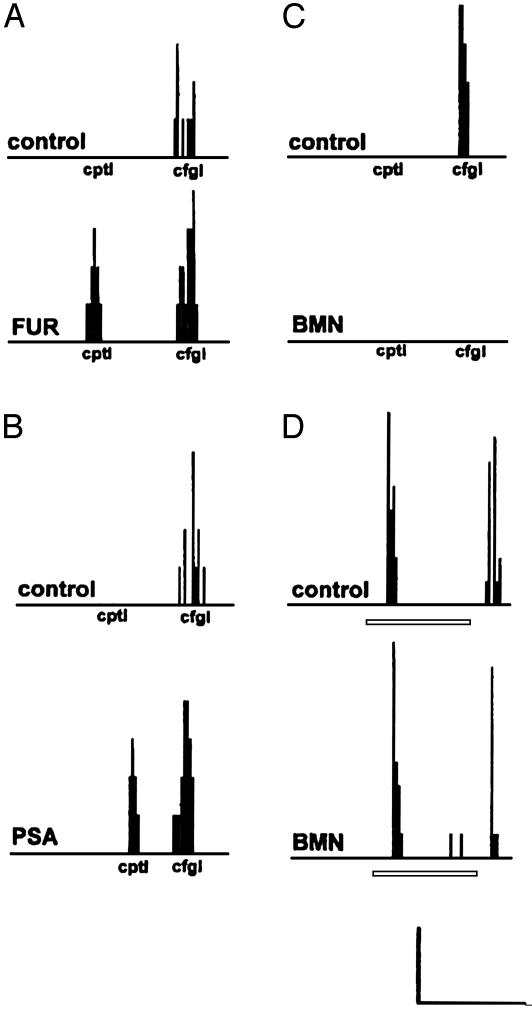

Fig. 3.

Chloride cotransporters and the transmembrane chloride gradient mediate the directional responses of SAC dendrites. SACs generated spikes to slit stimuli that moved centrifugally (cfgl) but not to stimuli that moved centripetally (cptl), indicating that the dendrites of SACs generate DS light responses. (A and B) Superfusion of 25 μM FUR (A) or a small reduction of the transmembrane chloride gradient by replacing 15 mM Cl- in Ringer's solution with 15 mM PSA (B) eliminated this selectivity by introducing a response to stimulus movement from the periphery to the soma. (C) In contrast, superfusion of 10 μM BMN eliminated this selectivity also but did so by decreasing the response to stimulus movement from the soma to the periphery. [Scale bar (bottom of figure) in A–C represents 1 s (x axis) and 2 spikes (y axis).] (D) Although SACs did not respond to moving stimuli after BMN application, they retained their response to stationary flashing spots of light. Horizontal bars represent the time of occurrence of stationary flashing, full-field light stimuli. In A–C, extracellular spike activity of single SACs to slits of light (0.5 × 0.03 mm) that were moved a single time at 0.5 mm/s in the centripetal and centrifugal directions is shown in histogram form (see also Fig. 4). (Scale bar in D: x axis, 2 s; y axis, 3 spikes.)

Superfusion of FUR (25–50 μM) (Fig. 3A) or replacement of 15 mM Cl- with PSA in Ringer's solution (Fig. 3B) eliminated the directional selectivity of SAC dendrites in every case tested (FUR, n = 6; PSA, n = 6), by introducing a response to stimulus movement from the periphery to the soma. In contrast, superfusion of BMN (10–100 μM) also eliminated this selectivity in every case tested (n = 6), but it did so by decreasing the response to stimulus movement from the soma to the periphery (Fig. 3C). Although the displaced SACs did not respond to moving stimuli after BMN application, they retained their ON–OFF response (12, 13) to stationary flashing spots of light (Fig. 3D) as they also did after replacement of 15 mM Cl- with PSA (data not shown). The finding that BMN and FUR acted in opposite ways when they eliminated the directional responses of both DS ganglion cells and SACs is consistent with the selectivity of BMN and FUR for the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters, respectively.

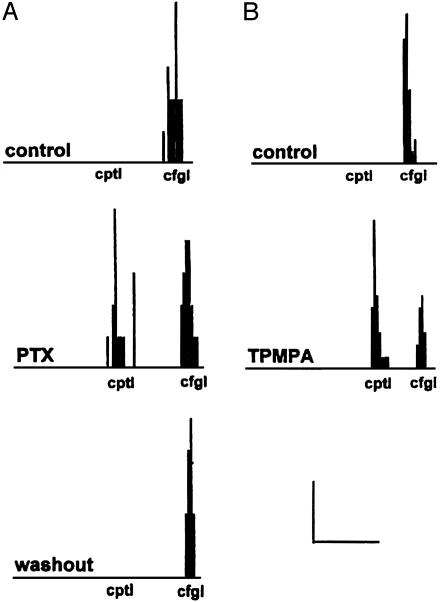

Because stimulus movement in the centripetal direction hyperpolarizes SACs (Fig. 2A) and the directional responses of SAC dendrites are highly sensitive to the transmembrane chloride gradient (Fig. 3), we also tested whether the directional responses of SACs are mediated by GABAA and GABAC receptor activation. As shown in Fig. 4, picrotoxin (50–100 μM; n = 5), a GABAA and GABAC antagonist, and TPMPA [(1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid] (50 μM; n = 5), a selective GABAC antagonist, eliminated the directional responses of SAC dendrites in every case tested by introducing a response to stimulus movement from the periphery to the soma. This finding suggests that GABAC receptors mediate the directional responses of SAC dendrites because the GABAA antagonists bicuculline and SR-95531 do not affect their directional responses (5).

Fig. 4.

GABAC receptor activation mediates the directional responses of SAC dendrites. Application of picrotoxin (PTX) (A; 50 μM), a GABAA and GABAC antagonist, or TPMPA [(1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid] (B; 50 μM), a selective GABAC antagonist, eliminated the directional responses of SAC dendrites by introducing a response to stimulus movement from the periphery to the soma. Slits of light (0.5 × 0.03 mm) were moved at 0.5 mm/s in the centripetal and centrifugal directions without stopping (see also Figs. 2 and 3). Responses to a single movement of the slit stimulus in the centrifugal and centripetal directions are shown (see also Figs. 2 and 3). (Scale bar in A: x axis, 1 s; y axis, 2 spikes. Scale bar in B: x axis, 1 s; y axis, 3 spikes.)

Discussion

These results indicate that chloride cotransporters mediate GABA-dependent directional selectivity. That is, blockade of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter with BMN and blockade of the K–Cl cotransporter with FUR eliminated the directional responses of ON–OFF DS ganglion cells and SAC dendrites. In addition, reduction of the transmembrane chloride gradient by replacing 15 mM Cl- with 15 mM PSA also eliminated the directional responses of DS ganglion cells and SACs. These findings demonstrate that direction selectivity is exquisitely sensitive to the ECl and indicate that chloride cotransporters, which regulate the intracellular chloride concentration and thus the transmembrane chloride gradient, play a key role in the generation of direction selectivity.

BMN and FUR eliminated the direction selectivity of starburst dendrites and DS ganglion cells in an opposite fashion for each cell type and in a manner that indicates that SACs provide a GABA-mediated, sign-inverting input to DS ganglion cells. That is, although BMN and FUR increased and decreased the responsiveness of DS ganglion cells to moving stimuli (Fig. 1), respectively, they had opposite effects on SACs (Fig. 3), suggesting that transmission from SACs to DS ganglion cells is mediated by a GABAergic synapse (6).

Although the location of the chloride cotransporters that mediate direction selectivity is not known, the finding that blockade of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters eliminated the directional responses of starburst dendrites in opposite ways suggests that SACs express both types of chloride cotransporter and that the cotransporters are distributed differentially on SAC dendrites. Moreover, the finding that stimulus movement in the centripetal direction evoked a clear hyperpolarization of the SAC (Fig. 2 A) indicates that the directional responses of SAC dendrites cannot be explained solely on the basis of a GABA-mediated shunt of excitation (17) or solely on the basis of the cable properties of their dendrites (18). Rather, our findings indicate that a GABAA receptor- GABAC receptor-evoked hyperpolarization that is K–Cl cotransporter-dependent likely mediates the SAC response to stimulus movement in the centripetal direction.

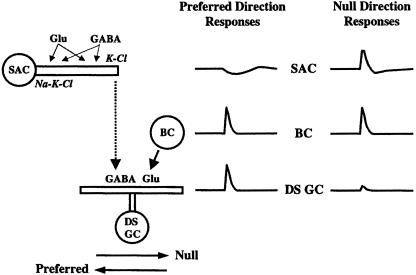

The Fig. 5 model, which is based on proposals in refs. 17 and 19, incorporates the above findings and observations, accounts for the directional responses of ON–OFF DS ganglion cells and SACs, and is consistent with the extant literature on these cells. The model incorporates the DS ganglion cell, a nondirectional bipolar cell that provides excitatory, glutamate-mediated input to the ganglion cell (20), and the SAC that provides GABA-mediated DS, inhibitory input to the ganglion cell that shunts the excitatory input from the bipolar cell. Fig. 5 illustrates directional signaling to a DS ganglion cell from a SAC dendrite pointing in the null direction of the ganglion cell (6). In the model, the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters are located on the proximal and distal portions of the SAC dendrites, respectively. In addition, the SAC expresses GABA (21) and glutamate (22, 23) receptors, which are located along the entire length of its dendrites, and releases GABA (24–26) from the distal tips of its dendrites (20, 27, 28) onto the DS ganglion cell. The glutamatergic bipolar cell and GABAergic amacrine cell that provide input to the SAC are not depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Model of direction selectivity consistent with the present data and the extant literature on rabbit ON–OFF DS ganglion cells and SACs. A nondirectional bipolar cell (BC) provides excitatory glutamate-mediated input to the ganglion cell (GC), and the SAC provides GABA-mediated DS inhibitory input to the ganglion cell that shunts the excitatory input from the bipolar cell. Directional signaling from a SAC dendrite to a dendrite of its recipient DS ganglion cell is illustrated. The Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters are located on the proximal and distal portions of the SAC dendrites, respectively. In addition, GABA release from the SAC is primarily from the distal tips of its dendrites. Circles represent cell bodies, and rectangles represent dendritic processes. See Discussion for details.

According to Fig. 5, when a stimulus moves across the receptive field of the SAC, both glutamate and GABA will be released onto it. If the stimulus moves from left to right, the null direction for the DS ganglion cell illustrated in Fig. 5, the SAC dendrite will initially be depolarized and then hyperpolarized as GABA is released initially onto the proximal and then onto the distal dendrite of the cell. The initial depolarization and subsequent hyperpolarization of the distal tip of the SAC is illustrated to the right of the cell in Fig. 5. This biphasic response occurs because GABA depolarizes neurons when ECl > ERP (the resting membrane potential) because of the action of the Na–K–Cl cotransporter (9) and hyperpolarizes neurons when ECl < ERP because of the action of the K–Cl cotransporter (7, 9). The GABA-evoked depolarization to stimulus movement in the centrifugal direction may also be augmented by the depolarizing effect of glutamate. As the initial depolarizing wave reaches the distal dendrite of the SAC, GABA will be released from the distal dendrite. The response of the DS ganglion cell to excitatory input from the bipolar cell will be shunted when it receives the coincident GABA input, so that a null direction response is generated, as shown to the right of the DS ganglion cell in Fig. 5. In contrast, if a slit of light moves from right to left, the preferred direction for the DS ganglion cell, the distal dendrite of the SAC will be hyperpolarized because of the activity of the K–Cl cotransporter. The hyperpolarization is shown to the right of the SAC in Fig. 5. GABA release from the distal tip of the SAC dendrite will, therefore, be minimal. As a result, excitatory input from the bipolar cell will dominate and the ganglion cell will produce a preferred-direction response, as shown to the right of the DS ganglion cell in Fig. 5.

The difference in the response of the SAC to stimulus movement in the centrifugal and centripetal directions may be enhanced by the presence of GABAC, rather than GABAA, receptors (Fig. 4) along the length of the SAC dendrite. The response kinetics of GABAC receptors are slower than that of GABAA receptors (29), so that the GABA-evoked depolarization and hyperpolarization of the SAC dendrite to stimulus movement in the centrifugal and centripetal directions, respectively, may be relatively sustained. In fact, the relatively long duration of the hyperpolarization that is evoked by centripetal motion (Fig. 2 A) may be a key component in the generation of the directional responses of SAC dendrites. In contrast, the relatively faster depolarization that is evoked by centrifugal motion (Fig. 2 A) may occur because this response is mediated in part by glutamate receptor activation (23).

Therefore, GABA release from the distal dendrite of the SAC occurs primarily in the null direction and significantly less in the preferred direction because in the null, but not in the preferred, direction the distal tip of the SAC dendrite is depolarized by Na–K–Cl cotransporter-mediated GABA-evoked chloride efflux. Thus, according to the model, directional responses in the DS ganglion cell are generated by two asymmetries along the length of the SAC dendrite: one in the differential distribution of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters and one in the location of the GABA release site at the distal tip of the starburst dendrite. These asymmetries produce a DS release of GABA from the SAC onto the DS ganglion cell dendrite. Recent evidence suggests that nonvesicular, carrier-mediated GABA release, which may be the primary mechanism of GABA release from SACs (26), may be sensitive to small changes in membrane potential (30).

There is precedence for the idea that the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters are distributed differentially in neurons. In the retina, the Na–K–Cl cotransporter is restricted to the dendrites of rod bipolar cells, whereas the K–Cl cotransporter is located on their axon terminals (8), suggesting that GABA depolarizes the dendritic processes of these cells and hyperpolarizes the axon terminals. Elsewhere in the adult CNS, GABAA and GABAC receptor activation can evoke both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing postsynaptic potentials from the same neuron (31). Moreover, different compartments of a single neuron have been reported to contain different intracellular chloride concentrations (32, 33) in a manner that is consistent with the differential distribution of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters in the membranes of the proximal and distal portions of the dendrites, respectively. In addition, SAC dendrites exhibit a differential distribution of synaptic proteins because synaptic specializations are present on the distal, and not proximal, portions of their dendrites (20, 27, 28).

The BMN and FUR results necessitate that the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters are in a location that is presynaptic to the DS ganglion cell, such as on the SAC. If they were on the DS ganglion cell itself, then BMN and FUR would produce effects opposite from those obtained in our study. For example, if the ganglion cell expressed the Na–K–Cl cotransporter, then BMN application would have reduced its light responses, a finding opposite to the finding that we obtained. Similarly, if the ganglion cell expressed the K–Cl cotransporter, then FUR application would have increased its light responses, a finding also opposite to the finding that we obtained. The Fig. 5 model incorporates a GABA-mediated shunting inhibition on the DS ganglion cell itself that is not mediated by the K–Cl cotransporter and, thus, not sensitive to FUR. A recent study has shown that an increase in intracellular chloride in the DS ganglion cell or depolarization of the DS ganglion cell alters the degree of direction selectivity (34). This finding is consistent with the idea illustrated in Fig. 5 that GABA input to the DS ganglion cell is itself directional and that GABA input to the DS ganglion cell during stimulus movement in the null direction shunts coincident excitatory input.

The Fig. 5 model is consistent with the BMN, FUR and chloride replacement results reported here. As described above (Fig. 1), BMN eliminated the directional responses of DS ganglion cells by increasing the responses to motion in the null direction. According to the model, BMN, which blocks Na–K–Cl cotransporter activity, would result in the SAC hyperpolarizing to stimulus motion in all directions. Fig. 3C illustrates that BMN had this effect on the SAC. The DS ganglion cell, which receives nondirectional excitatory input from the bipolar cell and sign-inverting GABA-mediated inhibition from the SAC, would then be excited by stimulus motion in all directions, as shown in Fig. 1 A and B. In contrast, FUR, which blocks K–Cl cotransporter activity, would result in the SAC depolarizing to stimulus motion in all directions. Fig. 3A illustrates that FUR had this effect on the SAC. The DS ganglion cell would then respond to a lesser extent to stimulus motion in all directions, as shown in Fig. 1 C and D. In addition, the Fig. 5 model is consistent with the finding that replacing superfusate Cl- with PSA, an anion that does not traverse Cl- channels, would lower the driving force of Cl- into cells and thus increase Cl- efflux, an effect similar to that of FUR. Thus, the similar results obtained with PSA and FUR on DS ganglion cells (Fig. 1) and on SACs (Fig. 3) support the view that 25–50 μM FUR selectively blocks K–Cl cotransport and that, by doing so, it reduces the driving force of Cl- into cells. Moreover, although it has been reported that FUR selectively antagonizes α6 and α4 subunit-containing GABAA receptors, compared with other GABAA receptor types (35), it is unlikely that the effects of FUR reported here are mediated by GABAA receptor antagonism. This is because (i) the effect of FUR on DS ganglion cells is opposite that of picrotoxin (Fig. 1) and (ii) the directional response of SAC dendrites is mediated by GABAC, rather than GABAA, receptors (Fig. 4).

In summary, our findings demonstrate that blockade of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters and reduction of the transmembrane chloride gradient eliminate the directional responses of SAC dendrites and DS ganglion cells. These results indicate that the chloride cotransporters play a key role in the generation of direction selectivity and that direction selectivity is highly sensitive to the transmembrane chloride gradient. Also, the results suggest that the asymmetric distribution of the chloride cotransporters along SAC dendrites mediates direction selectivity by producing a DS release of GABA from the SAC dendrite onto the DS ganglion cell dendrite. Finally, the results suggest that subcellular specializations, such as the differential distribution of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters, can mediate the neural computation of complex information. As occurs in the retina, it is likely that the differential distribution of the Na–K–Cl and K–Cl cotransporters may also mediate neural computations elsewhere in the brain, such as in the midbrain and hippocampus, where the processes of individual neurons exhibit a chloride gradient (32, 33). Indeed, the asymmetric release of GABA from interneurons in the brain at dendrodendritic synapses may be an important means by which the brain processes information.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Chris Strang for help with some of the initial experiments; Drs. Frank Amthor, Michael Brenner, Christophe Ribelayga, and Charles Venglarik for helpful discussions; and Dr. Douglas McMahon for reading an early draft of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants EY014235, EY005102 (to S.C.M.), EY007845 (to K.T.K.), and HD38985; National Science Foundation Grant IBN-9819981 (to S.C.M.); and National Eye Institute CORE Grant EY03039 (to the University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL).

Abbreviations: DS, directionally selective; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GABAA, GABA type A; SAC, starburst amacrine cell; GABAC, GABA type C; ECl, chloride equilibrium potential; BMN, bumetanide; FUR, furosemide; PSA, pentanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Barlow, H. B., Hill, R. M. & Levick, W. R. (1964) J. Physiol. (London) 173, 377-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldwell, J. H., Daw, N. W. & Wyatt, H. J. (1978) J. Physiol. (London) 276, 277-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ariel, M. & Daw, N. W. (1981) J. Physiol. (London) 324, 161-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida, K., Watanabe, D., Ishikane, H., Tachibana, M., Pastan, I. & Nakanishi, S. (2001) Neuron 30, 771-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Euler, T., Detwiler, P. B. & Denk, W. (2002) Nature 418, 845-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried, S., Munch, T. A. & Werblin, F. S. (2002) Nature 420, 411-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne, J. A. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 273, C1516-C1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vardi, N., Zhang, L.-L., Payne, J. A. & Sterling, P. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 7657-7663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell, J. M. (2000) Physiol. Rev. 80, 211-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mangel, S. C. (1991) J. Physiol. (London) 442, 211-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tauchi, M. & Masland, R. H. (1984) Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 223, 101-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen, R. J. (1995) Visual Neurosci. 12, 177-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomfield, S. A. (1992) J. Neurophysiol. 68, 711-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen, E. D. (2001) Visual Neurosci. 18, 799-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor, W. R. & Wassle, H. (1995) Eur. J. Neurosci. 7, 2308-2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters, B. N. & Masland, R. H. (1996) J. Neurophysiol. 75, 469-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borg-Graham, L. J. & Grzywacz, N. M. (1992) in Single Neuron Computation, eds. McKenna, T., Davis, J. & Zornetzer, S. F. (Academic, New York), pp. 347-376.

- 18.Poznanski, R. R. (1992) Bull. Math. Biol. 54, 905-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaney, D. I. (1990) in Progress in Retinal Research, eds. Osborne, N. & Chader, G. (Pergamon, Oxford), Vol. 9, pp. 49-100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Famiglietti, E. V. (1991) J. Comp. Neurol. 309, 40-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandstatter, J. H., Greferath, U., Euler, T. & Wassle, H. (1995) Visual Neurosci. 12, 345-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen, E. D. & Miller, R. F. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1127-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marc, R. E. (1999) J. Comp. Neurol. 407, 47-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaney, D. I. & Young, H. M. (1988) Brain Res. 438, 369-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brecha, N., Johnson, D., Peichl, L. & Wassle, H. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 6187-6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Malley, D. M., Sandell, J. H. & Masland, R. H. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12, 1394-1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Famiglietti, E. V. (1985) J. Neurosci. 5, 562-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandon, C. (1987) Brain Res. 426, 119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian, H. & Ripps, H. (2001) Prog. Brain Res. 131, 295-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu, Y., Wang, W. & Richerson, G. B. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 2630-2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaila, K. (1994) Prog. Neurobiol. 42, 489-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarolimek, W., Lewen, A. & Misgeld, U. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 4695-4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsch, W., Hormuzdi, S., Straube, E. Lewen, A. Monyer, H. & Misgeld, U. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 8339-8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, W. R., Shigang, H., Levick, W. R. & Vaney, D. I. (2000) Science 289, 2347-2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maksay, G., Korpi, E. R. & Uusi-Oukari, M. (1998) Neurochem. Int. 33, 353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]