Abstract

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) recurrence with accelerated fibrosis following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is a universal phenomenon. To evaluate mechanisms contributing to HCV induced allograft fibrosis/cirrhosis, we investigated HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells and their induction in OLT recipients with recurrence utilizing 51 HCV+ OLT recipients, 15 healthy controls and 9 HCV- OLT recipients. Frequency of HCV specific CD4+ Tcells secreting IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-10 was analyzed by ELISpot. Serum cytokines and chemokines were analyzed by LUMINEX. Recipients with recurrent HCV induced allograft inflammation and fibrosis/cirrhosis demonstrated a significant increase in frequency of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells. Increased pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-17, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1), decreased IFN-γ, and increased IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10 levels were identified. OLT recipients with allograft inflammation and fibrosis/cirrhosis demonstrated increased frequency of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) that inhibited HCV specific CD4+Th1 but not Th17 cells. This suggests that recurrent HCV infection in OLT recipients induces an inflammatory milieu characterized by increased IL-6, IL-1β and decreased IFN-γ which facilitates induction of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells. These cells are resistant to suppression by Tregs and may mediate an inflammatory cascade leading to cirrhosis in OLT recipients following HCV recurrence.

Keywords: transplantation, viral, T cell, inflammation

Introduction

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) recurrence is universal following orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) with an accelerated rate of fibrosis in the allograft compared to that in the native liver in chronic HCV(1, 2). T cell immunity to HCV structural and non-structural antigens determine the outcome following HCV infection (3, 4) and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are important effector arms in HCV immunity. In contrast to other viral infections, CD8+ T cells response to HCV is less significant in viral clearance(5, 6). This is substantiated by persistent HCV in patients with high HCV specific CD8+ T cells which display poor lytic capacity and impaired IFN-γ and TNF-α production (7). In contrast, CD4+ T cells play an important role in HCV immunity by secreting cytokines which stimulate CD8+ T and B cells (8–10). Several reports (11, 12), including from our laboratory (13) suggest that patients who exhibit multi-specific CD4+ T helper type 1 (Th1) responses against HCV have increased resistance to cirrhosis, and patients who exhibit T helper type 2 (Th2) responses demonstrate enhanced allograft fibrosis.

T helper type 17 (Th17) cells are implicated in inflammatory conditions associated with liver fibrosis (14–19). IL-17, the cytokine secreted by CD4+Th17 cells, is pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic (20, 21). It stimulates IL-8 and growth related oncogene alpha (Gro-α) from hepatic stellate cells promoting neutrophil influx into the liver (14). Inflammatory mediators which are over expressed in patients with HCV induced hepatic inflammation and fibrosis also enable the accumulation of mononuclear infiltrates. (22–26). The role of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells in recurrent HCV following OLT has not been characterized. Our objective was to determine the role of inflammatory cytokines in inducing HCV specific Th17 cells and characterize their role in recurrent HCV induced allograft inflammation and fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

Fifty-one OLT recipients (OLTr) for HCV cirrhosis who developed HCV recurrence and five non transplant chronic HCV patients were enrolled. HCV recurrence was confirmed by HCV+ RNA quantitative PCR (detection limit of 50 IU/mL - Cobas Amplicor, Roche Diagnostics), anti-HCV Ab by ELISA (Abbot Laboratories, Chicago) and liver histology. Patients with HBV and/or HIV were excluded. Patients were at least 12 months post-OLT to avoid confounding effect of early post-transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury. Blood samples and protocol biopsy was obtained concurrently on the same day of follow up. Fifteen HCV- healthy subjects and 9 non HCV OLTr were included as controls.

Histology

Pathologists classified liver biopsy based on Scheuer’s scoring system for necroinflammatory activity (Grade, G) and fibrosis (Stage, S) into 3 groups. Group 1 -patients with absent/minimal evidence of allograft fibrosis (S0-S2) and varying grades of allograft inflammation (G0-G4). Group 2 with moderate/severe fibrosis/cirrhosis (S3-S4) and either absent/minimal lobular/portal inflammatory activity and interface hepatitis (G0-G2) and Group 3 with moderate/severe fibrosis/cirrhosis (S3-S4) and moderate/severe interface hepatitis and hepatocellular damage (G3-G4).

Isolation of Serum and PBMCs

Serum and PBMCs were isolated from blood as described previously (13). Cells were used for experiments immediately after isolation or frozen in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide until use.

Antigen Stimulation

Recombinant HCV CORE, NS3, NS4, NS5 antigens (Viral Therapeutics, Ithaca), PHA (Sigma, St. Louis) HIV Gp120 (Biosynthesis Inc, TX) were tested by LAL assay (Charles Rivers, Charleston) as endotoxin-free. PBMCs were stimulated overnight with antigens (5μg/mL) in 24-well plates (Corning Incorporated, NY) in humidified 5% CO2 at 37°C.

ELISpot

IFN-γ, IL-17 and IL-10 ELISpot assays were performed using CD4+ T cells purified from PBMCs by negative selection using immunomagnetic separation cocktails (Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) with > 95% enrichment. CD4+ T cells (3×105 cells/well in triplicates) were incubated with autologous irradiated (3000 rads) CD4 depleted PBMCs as APCs (1:1 ratio) and antigen (5μg/mL) for 48–72hrs in 5% CO2 at 37°C. IFN-γ and IL-10 (BD biosciences, San Jose) and IL-17 ELISpot (eBioscience, San Diego) were performed per manufacturer’s instructions. Spots were analyzed in ImmunoSpot Image Analyzer (Cellular Technology, Cleveland). Cells cultured in medium (Cellular Technology, Cleveland) and irrelevant peptide (HIV Gp120 – Biosynthesis, TX) was used as negative control, and PHA as positive control for each sample. Spots in the experimental wells greater than two standard deviations of that obtained in the negative control wells were considered significantly positive and were expressed as spots per million cells (spm).

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Unconjugated and fluorochrome-conjugated mouse anti-human CD3, CD4, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD25, CD127 and isotype control Abs were obtained (BD Biosciences, San Jose). CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells were stained (eBioscience, San Diego) and analyzed using BD LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose). Purified CD4+ T cells labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45RA and APC conjugated anti-CD45RO Abs were sorted into CD3+CD4+CD45ROhighCD45RA-(Memory) or CD3+CD4+CD45RO-CD45RAhigh (Naïve) T subsets using BD Aria II High Speed Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose) with purity of >95%. CD4+ T cells were incubated with HCV CORE antigen (5μg/mL) and APCs in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated AB- human sera for 48hrs. Monensin (1μg/mL) was added during last 6 hours of stimulation. Surface staining was performed with flurochrome conjugated Abs and cells were permeabilized to stain intracellular PE conjugated anti-IL-17 Ab (eBioscience, San Diego) and fixed and analyzed. Analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tristar, San Carlos).

Multiplex bead Immunoassays

Serum cytokines (IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-2R, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF) and chemokines (MIP-1c, MIP-1b, IP-10, MIG, Eotaxin, RANTES, MCP-1) were measured using Multiplex Bead immunoassays (Invitrogen, Carlsbad) (31). Luminex xMAP™ system was used to read plates (Fisher, Pittsburgh). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of experimental wells was compared against a standard curve for concentration and expressed in pg/mL.

Co-culture assays

CD4+CD25+ Tregs were separated from PBMCs using immunomagnetic separation (Stem cell Technologies, Canada). CD4+ T cells were negatively purified using non-CD4 depletion mixture followed by positive selection of CD25+ Tregs with purity of >95 %. CD4+CD25+ Tregs were activated overnight with anti-CD3/CD28 Abs (Dynal Biotech). CD4+ T cells were depleted of CD25+ T cells using additional anti-CD25 magnetic bead with purity of resulting CD4+CD25- T cell (Teff) >95%. PBMCs depleted by anti-CD25 beads and irradiated at 3000 rads were used as APCs. Activated Tregs and Teff (3×105 cells/well) were incubated with autologous irradiated APCs and individual antigens (5μg/mL) at varying Treg:Teff ratios (0:1,1:16, 1:8, 1:4,1:2, 1:1) for 48–72hrs and analyzed by ELISpot.

Neutralization studies

mAbs to human IL-10 (clone 25209), IFN-γ (clone 25723), IL-6 (clone 1936), IL-1β (clone 8516) and corresponding isotype controls were obtained (R&D systems, Minneapolis). PBMCs were incubated with irradiated APCs and antigen (5μg/mL) with anti-IL 10, anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-6 or IL-1β (all at 10μg/mL) in 24 well plates for 8–10 days in 5% CO2 at 37°C. HCV antigen specific CD4+ T cell responses were determined using ELISpot.

Induction of HCV CORE specific IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in vitro

PBMCs from patients (Group1 and 2, n=5 each) and controls (n=5) were incubated with HCV CORE (5μg/mL) for 8–10 days in 5% CO2 at 37°C with 25% pooled sera derived from Group 3 (n=5) in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2mM L-glutamine, 20mM HEPES, 100U/mL penicillin, and 100μg/mL streptomycin in 24 well plates (Corning Incorporated, NY). PBMCs incubated with 25% autologous sera or normal AB negative sera served as controls. PBMCs in experimental and control cultures were incubated in separate wells with combination of neutralizing Abs to IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-1β (all at 10μg/mL) or matched isotype control Abs. Controls were used to rule out the possibility of interference by the active HCV particles during the measurement of HCV CORE specific responses. At end of culture, CD4+ T cells were selected by immunomagnetic separation (Stem Cell Tech, Canada) and HCV specific CD4+ T cell responses were evaluated via ELISpot.

Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

RNA was extracted from sorted CD4+ T cells with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized with Superscript IIITM First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Quantitative real time PCR was performed with Taqman to determine RORC and Foxp3 expression using Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression Probes (Applied Biosystems) (27). GAPDH was used to normalize expression levels of target gene. Relative target gene expression was calculated using 2-ΔΔCt method.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism v5.0b (La Jolla, CA), SAS v9.2, and Enterprise guide v2.2 (Cary, NC) software was used. Continuous variables were compared using Kruskal Wallis test with post-hoc Dunn’s multiple comparisons while categorical variables were compared using Fischer’s exact tests. Mann-Whitney test determined differences in frequency of CD4+ T cells or cytokine levels between two groups and correlation analyses were performed using Spearman rank test. Two-sided level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Of 51 patients, 23 (Group 1) demonstrated histological evidence of no/minimal to moderate allograft fibrosis (S0-S2) with varying grades of allograft inflammation (G0-G4). Severe fibrosis or cirrhosis (S3-S4) was noted in 28 patients (Groups 2 and 3). Of the 28, 15 (Group 2) demonstrated low grade allograft inflammation (G0-G2) while 13 (Group 3) demonstrated high grade inflammation (G3-G4) consistent with moderate/severe hepatic inflammation and/or bridging confluent necrosis. No significant difference was noted in clinical demographics; however, Group 3 had higher levels of transaminases (ALT; p=0.001, AST; p=0.007) (Table 1). Mean age and follow up (time of obtaining patient sample and biopsy) were similar (Table 1). Co-existent alcohol intake was seen in 7(30%), 4(26%) and 4(30%) of the patients in groups 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Serum and PBMCs from 15 healthy individuals and 9 non-HCV OLTr were included as controls (alcohol (4), cryptogenic (2), cholangiocarcinoma (1) and primary biliary cirrhosis (2)).

Table 1.

Clinico-demographic profile of OLT recipients with HCV recurrence in Group 1 (Scheuer G0-4 S0-2), Group 2 (Scheuer G0-2, S3-4), Group 3 (Scheuer G3-4, S3-4)

| Group 1 (n=23) | Group 2 (n=15) | Group 3 (n=13) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 54.1±3.8 | 54.6 ±4.3 | 53.5±3.9 | 0.80 |

| Gender (M:F) | 13:10 | 7:8 | 8:5 | 0.77 |

| Ethnicity | 0.91 | |||

| Caucasian | 13 | 9 | 7 | |

| African-American | 7 | 3 | 3 | |

| Others | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Mean Follow up time since OLT (mo) | 18.3±4.5 | 20.6±5.6 | 17.5±4.5 | 0.29 |

| Fibrosis stage(S) | 0–1 | 2–4 | 2–4 | |

| Inflammatory Grade (G) | 0–4 | 0–2 | 3–4 | |

| HCV genotype | 0.82 | |||

| 1 | 13 | 9 | 6 | |

| Non-1 | 10 | 6 | 7 | |

| HCV load (log IU/ml) | 6.3±1.6 | 6.2±0.9 | 6.4±1.5 | 0.54 |

| Pre-transplant CTP scores | 0.97 | |||

| 5–6 | 8 | 7 | 4 | |

| 7–9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | |

| 10–15 | 6 | 2 | 3 | |

| ALT [Mean(range)] IU/ml | 111(45–326) | 124(39–439) | 272(50–620) | 0.001 |

| AST [Mean(range)] IU/ml | 103(26–271) | 93(31–280) | 182(61–415) | 0.007 |

| Coexistent Alcohol | 7(30.4%) | 4(26.7%) | 4(30.7%) | 1.00 |

| CMV status | 0.99 | |||

| D+R− | 1(4%) | 1(6%) | 0(0%) | |

| D−R+ | 5(21.7%) | 4(26.7%) | 4(30.7%) | |

| D+R+ | 9(39.1%) | 6(40%) | 5(38.5%) | |

| D−R− | 8(34.7%) | 4(26.7%) | 4(30.7%) | |

| No. of acute rejection | 6(26%) | 4(26.7%) | 5(38.5%) | 0.73 |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| Tacrolimus | 17(73.91%) | 10(66.67%) | 9(69.23%) | 0.85 |

| Cyclosporine | 3(13.04%) | 2(13.33%) | 2(15.38%) | |

| Sirolimus | 3(13.04%) | 3(20%) | 1(7.6%) | |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil (Cellcept) | 13(56.5%) | 8(53.34%) | 8(61.5%) | 0.42 |

| Mycophenolate Sodium (Myfortic) | 2(8.6%) | 2(13.33%) | 1(7.6%) | |

| Prednisone | 23(100%) | 15(100%) | 13(100%) | 1.00 |

Increased serum levels of IL-17, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8 and MCP-1 in recipients with high grade allograft inflammation and fibrosis/cirrhosis

Serum cytokines and chemokines were measured by immunoassays and analyzed using LUMINEX (Table 2). In contrast to Groups 1 and 2, Group 3 demonstrated significantly increased levels of IL-17, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8 and MCP-1. Serum IFN-γ levels were significantly decreased in both Groups 2 and 3. Levels of Th2 cytokines: IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10 were significantly elevated in both Groups 2 and 3. No difference was noted in levels of other cytokines and chemokines (data not shown).

Table 2.

Serum Cytokine and Chemokine profile in OLT recipients with recurrent Hepatitis C – (Group 1 – Scheuer G0-4, S0-2; Group 2 Scheuer G0-2, S3-4; Group 3 Scheuer G3-4, S3-4). Concentrations expressed as mean ± SEM pg/mL

| Controls | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-17 | 43±18 | 60±19 | 26±18 | 187±39 | 0.001 |

| IL-6 | 89±51 | 178±40 | 185±73 | 832±198 | <0.0001 |

| IL-1β | 67±42 | 346±71 | 237±50 | 738±227 | 0.002 |

| IL-8 | 51±41 | 158±73 | 98±49 | 255±47 | 0.013 |

| MCP | 78±31 | 264±55 | 123±34 | 360±128 | 0.003 |

| IFN-γ | 53±22 | 311±78 | 128±38 | 114±29 | 0.008 |

| IL-4 | 71±35 | 85±64 | 220±103 | 157±62 | 0.035 |

| IL-5 | 45±21 | 56±21 | 220±58 | 241±86 | 0.042 |

| IL-10 | 65±57 | 110±42 | 294±133 | 290±73 | 0.039 |

Increased frequency of HCV specific CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-17 in recipients with high grade allograft inflammation and fibrosis

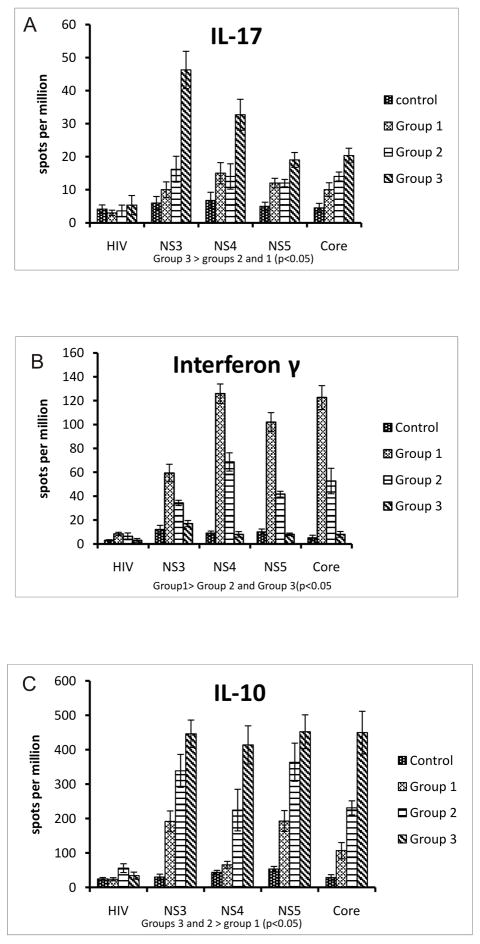

Frequencies of CD4+T cells specific to HCV antigens (NS3, NS4, NS5, CORE), irrelevant peptide (HIV Gp120 – negative control) and PHA (positive control) that secrete IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-10 were analyzed by ELISpot. When compared to controls, Group 1, and Group 2 OLTr in Group 3 demonstrated significant increases in frequency of CD4+ T cells secreting IL-17 in response to HCV antigens (mean ± SEM spots per million(spm) NS3: 6 ± 1.95 vs. 10 ± 2.36 vs. 16.2 ± 3.91 vs. 46.23 ± 5.63 p<0.05, NS4: 6.7 ± 2.4 vs. 15 ± 3.2 vs. 14 ± 3.83 vs. 32.67 ± 4.69 p<0.05, NS5: 5 ± 1.22 vs. 12 ± 1.46 vs 12 ± 1.10 vs 19 ± 2.25 p<0.05, CORE: 4.5 ± 1.35 vs. 10 ± 2.1 vs. 14 ± 1.34 vs 20 ± 2.34 p<0.05) (Figure 1A). Frequency of CD4+ T cells that secreted IL-17 in response to the irrelevant peptide and PHA did not differ among groups

Figure 1. Increased HCV specific IL17 and IL10 and decreased INF-γ CD4+ Tcell responses in HCV OLT recipients with recurrent HCV induce allograft fibrosis and high grade inflammation.

ELISpot comparing CD4+Tcell IL17(A), INF-γ(B) and IL10(C) response to HCV antigens (NS3, NS4, NS5, CORE) and non specific peptide (HIV Gp120) among four groups - Controls (Normal healthy patients and Non HCV OLT recipients), Group 1(Scheuer G 0-4, S 0-2), Group 2 (Scheuer G0-2, S3-4), Group 3 (Scheuer G3-4, S3-4). Values represented as mean ± SEM spots per million (spm) and significance calculated using Mann Whitney test. 3×105 CD4+ T cells were used per well and each antigen was cultured in triplicate.

Decreased frequency of HCV specific INF-γ secreting CD4+ T cells in recipients with allograft fibrosis

When compared to controls and Groups 2 and 3, patients in Group 1 demonstrated increased frequencies of HCV specific CD4+ Th1 cells that secrete IFN-γ against all HCV antigens (mean ± SEM spm; NS3: 12.45 ± 3.5 vs 34.33 ± 2.203 vs 17 ± 2.6 vs 59.4 ± 7.31, p<0.05, NS4: 9.77 ± 1.76 vs 68.76 ± 7.66 vs 8 ± 2.3 vs 125 ± 8.16 p<0.05, NS5: 10.86 ± 2.47 vs 41.67 ± 2.43 vs 8 ± 1.1 vs 102 ± 7.95 p<0.05, CORE: 5.63 ± 2.29 vs 52.6 ± 10.66 vs 8 ± 2.4 vs 122.6 ± 9.99 p<0.05) (Figure 1B).

Increased frequency of HCV specific CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-10 in recipients with allograft fibrosis

When compared to controls and Group 1, Groups 2 and 3 demonstrated increased frequency of CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-10 in response to HCV antigens (mean ± SEM spm; NS3: 30 ± 8.3 vs 192 ± 30.3 vs 338 ± 47.8 vs 446 ± 39.8 p<0.05, NS4: 43.8 ± 6.01 vs 66 ± 9.86 vs 224.8 ± 60.44 vs 414 ± 55.48 p<0.05, NS5: 53.46 ± 7.73 vs 193 ± 30.4 vs 363.8 ± 55.4 vs 452.3 ± 48.98 p<0.05, CORE: 29.2 ± 7.99 vs 107 ± 23.5 vs 231.2 ± 20.45 vs 449.67 ± 61.96 p<0.05) (Figure 1C).

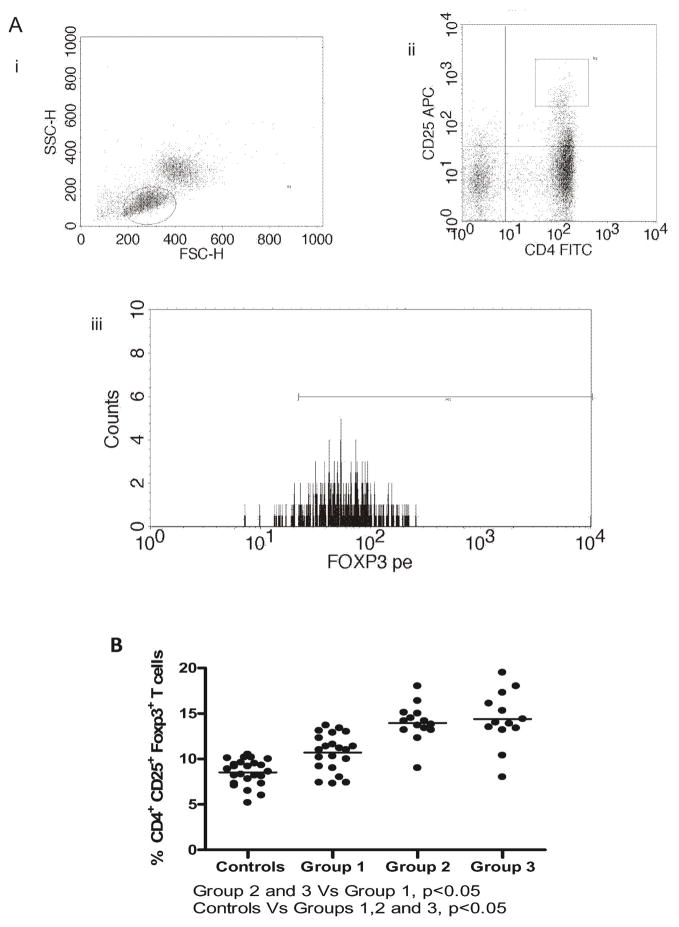

Increased frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory T cells (Tregs) in recipients with allograft fibrosis

Frequency of Tregs was assessed by FACS (Figure 2A). CD4+CD25+T cells with high intracellular Foxp3 were gated as Tregs. OLTr with HCV recurrence demonstrated increased frequency of Tregs compared to controls and non HCV OLTr (p<0.05). In sub-group analysis, increased frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells was demonstrated in Groups 2 and 3 compared to Group 1 and control.

Figure 2. Increased frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory T cells in OLT recipients who developed allograft fibrosis/cirrhosis following HCV recurrence.

(A) Schematic gating for CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. PBMCs were gated for leukocyte population(i) CD4(FITC) CD25(APC) double positive cells were gated(ii) Foxp3(PE)+ cells in the gated population were enumerated(iii) (B) Increased frequency of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in OLT recipients with HCV recurrence compared to non-HCV OLT and controls. OLT recipients with HCV induced allograft fibrosis (Group 2 – Scheuer G0-2 S3-4, Group 3 –Scheuer G3-4 S3-4) demonstrated increased frequencies of Tregs compared to OLT recipients with no/minimal allograft fibrosis (Group 1) (p<0.05). No statistically significant difference in the frequency of Tregs was observed between Groups 2 and 3.

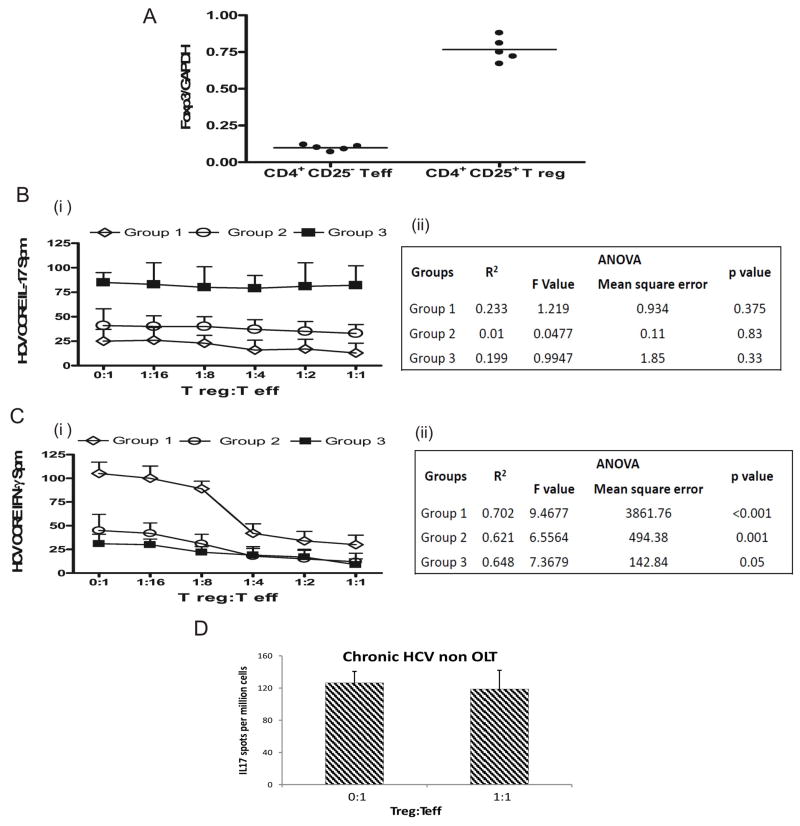

HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells but not CD4+Th1 cells demonstrate resistance to Treg and IL-10 mediated suppression

OLTr with fibrosis and high grade inflammation demonstrated increased IL-17 and decreased IFN-γ secreting CD4+ T cells specific to HCV, and increased Foxp3+ Tregs. To investigate the immunomodulatory role of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs on HCV specific Th1 and Th17 responses, we measured frequencies of HCV specific CD4+ T cells secreting IFN-γ or IL-17 using ELISpot by co-culturing CD25 depleted CD4+ effector T cells (Teff) and activated CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) (3×105 Teff cells per well and varying ratio of Tregs 0:1, 1:16, 1:8, 1:4, 1:2 and 1:1) in the presence of HCV CORE and autologous irradiated APCs. In order to avoid effects of alcohol and CMV status on HCV specific responses, patients from Group 1 (S0-S2, G0-G4), Group 2 (S3-S4, G0-G2), Group 3 (S3-S4, G3-G4) were selected only if they had no coexistent alcohol use and Donor-/Recipient- CMV status. CD4+CD25+ Tregs used for co-culturing expressed high levels of Foxp3 (Figure 3A). Addition of Tregs at varying ratios to Teff resulted in significant decrease in frequency of HCV CORE specific Teff secreting IFN-γ but not IL-17 (Figure 3B, C) in the 3 groups analyzed. We also performed a linear regression analysis and ANOVA to compare the Treg concentration dependant changes of the INF-γ and IL-17 responses. The suppression of INF-γ responses was significant (p<0.001, Figure 3B, C). Addition of Tregs even at higher ratios (10:1 or 20:1) did not alter IL-17 secretion (data not shown). We performed analysis on non transplanted chronic HCV patients (co-culturing Teff and Tregs at ratio 1:1) and found no decrease in HCV CORE specific IL-17 response in this group (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. HCV specific CD4+ Th17 cells but not CD4+ Th1 cells demonstrate resistance to Treg mediated suppression.

Five patients each (who had no confounding factors of co-existent alcohol intake and were both donor and recipient CMV negative) were selected from Group 1 (Scheuer G0-4 S0-2), Group 2(Scheuer G0-2, S3-4), Group 3 (Scheuer G3-4, S3-4). CD25 depleted CD4+ effector T cells (Teff) (3×105 cells/well) were co cultured with activated CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells(Treg) at varying ratios in the presence of HCV CORE antigen and autologous irradiated APCs and IL17 and INF-γ response measured using ELISpot. (A) - High Foxp3 expression(normalized with GADPH) in the isolated CD4+CD25+ T regulatory compared to CD4+CD25- T effector subsets using real time PCR before co-culture experiments. (B, C) - Tregs at increasing concentrations suppress the frequency of IFN-γ but not IL-17 secreting HCV CORE specific Teff in all the three groups analyzed. (B ii, C ii) – Results of Linear regression analysis and ANOVA to determine Treg number dependant change in responses. Decrease in INF-γ responses significant. (D) Tregs co cultured with Teff cells do not suppress HCV specific IL17 response in non transplant chronic HCV patients. Values in B (i), C (i), D represented as mean ± SEM in spots per million (spm)

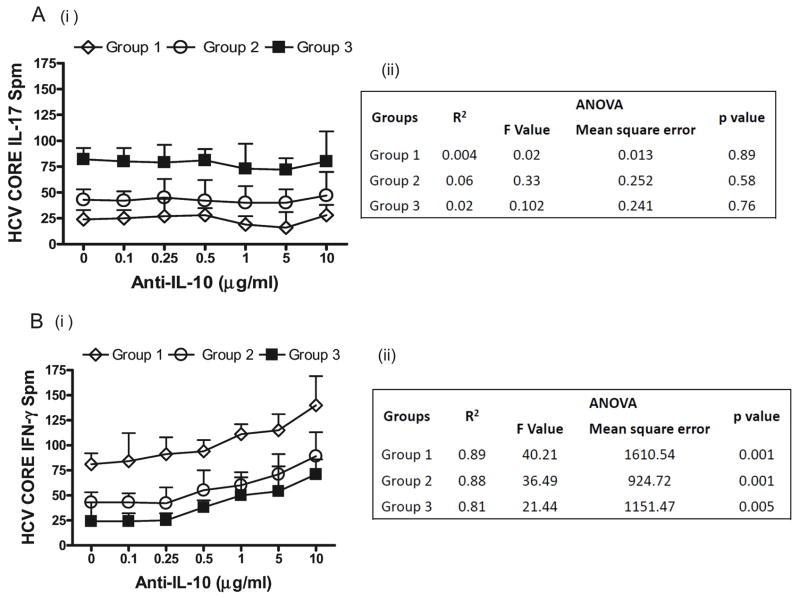

We also evaluated the frequencies of CD4+ T cells that secrete either IFN-γ or IL-17 in response to HCV CORE by ELISpot following addition of either anti-IL-10 neutralizing Abs (10μg/mL) or isotype control. Anti-IL-10 abs increased the frequency of HCV CORE specific IFN-γ but not IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in all three groups. Linear regression analysis revealed significant increase in INF-γ with increasing anti IL-10. This indicates that HCV specific CD4+ Th17 cells but not IFN-γ secreting CD4+Th1 cells demonstrate significant resistance to IL-10 mediated suppression during recurrent HCV infection post OLT (Figure 4).

Figure 4. In contrast to CD4+ Th1 cells, HCV specific CD4+ Th17 cells demonstrate resistance to IL-10 mediated suppression.

Frequencies of CD4+ T cells that secrete either IL-17(A) or INF-γ (B), in response to HCV CORE antigen were evaluated by ELISpot following addition of either anti-IL-10 neutralizing Abs (10μg/mL) or matched isotype control Abs. Anti-IL-10 neutralizing increase the frequency of HCV CORE specific IFN-γ but not IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in all the three groups analyzed. (An ii, B ii) Results of linear regression analysis and ANOVA to determine anti-IL-10 concentration dependant change in responses. Increasing anti-IL10 increased INF-γ responses. Values in A (i), B (i) represented as mean ± SEM spots per million cells.

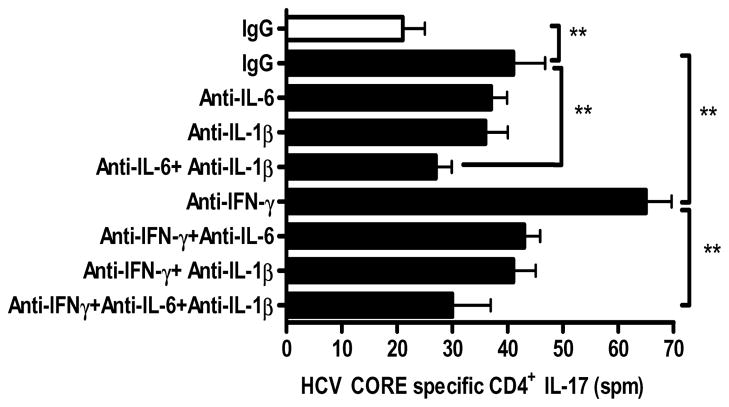

IFN-γ down modulates while IL-6 and IL-1β synergistically promote induction of HCV specific Th17 cells

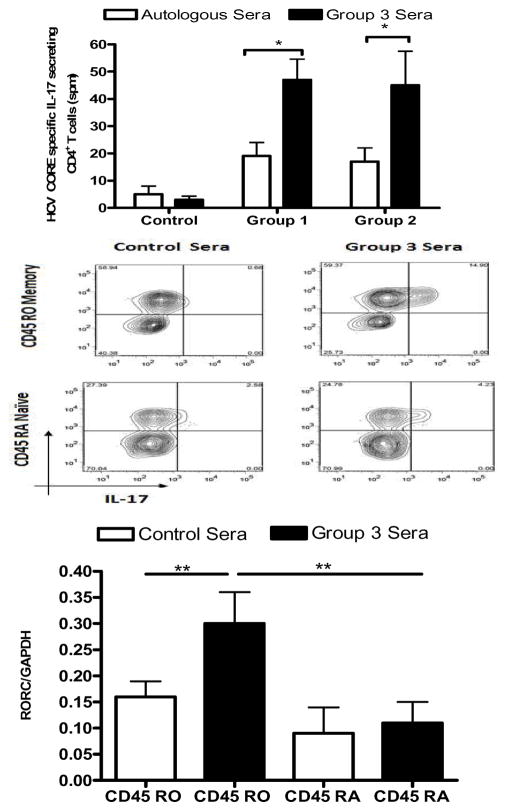

To evaluate the role of IFN-γ, IL-6 and IL-1β on the induction of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells, we used ELISpot to determine frequency of HCV CORE specific CD4+ T cells secreting IL-17 induced in vitro following neutralization of IFN-γ or IL-6 or IL-1β with appropriate mAbs. We induced HCV CORE specific CD4+Th17 cells in vitro using PBMCs from Group 1 (n=5) and Group 2 (n=5) (without co-existent history of alcohol use and D-/R- CMV status) and stimulating with HCV CORE for 8–10 days in 25% pooled sera derived from Group 3 patients that contained high levels of pro-Th17 associated factors, including IL-6 and IL-1β or in 25% autologous or AB- sera (control). PBMCs from healthy subjects served as control. Frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells derived from both Group 1 and 2 patients was significantly increased by 45.2±6 % in cultures incubated with 25% pooled sera derived from Group 3 patients when compared to those incubated in 25% control sera. CD4+ T cells from controls did not show significant change in frequency of HCV CORE specific IL-17 secreting cells (Figure 5A). Flow cytometric analysis was performed to assess phenotype of IL-17 secreting HCV CORE specific CD4+ T cells. Cells were first gated for CD4 positivity, and subsequently, analyzed for CD45RO-APC or CD45RA-FITC and IL17-PE double positivity. IL-17 secreting HCV CORE specific Th17 cells induced in vitro using Group 3 sera were enriched in memory T cell compartment (CD4+CD45ROhighCD45RAlow) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Induction of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells in vitro using sera derived from Group 3 patients containing high levels of pro-Th17 factors.

HCV CORE specific Th17 cells stimulated in vitro with HCV CORE antigen for 8–10 days in 25% pooled sera derived from Group 3 patients (Scheuer G3-4, S3-4; filled boxes) or 25% normal AB negative or autologous sera used as a control medium (open boxes) were measured by ELISpot using PBMCs derived from patients of Group 1(Scheuer G0-4 S0-2;n=5), Group 2 (Scheuer G0-2, S3-4; n=5) and control individuals (non HCV). Values represented as mean ± SEM spots per million cells (A) Increased HCV CORE specific Th17 response in Group 1 and Group 2 cultured in Group 3 sera when compared to those cultured in autologous serum or control individuals (B) IL-17 secreting HCV CORE specific Th17 cells induced in vitro using Group 3 sera were enriched in the memory T cell compartment (CD45ROhighCD45RAlow) when assessed by flow cytometry. (C) CD45ROhighCD45RAneg (Memory) and CD45ROnegCD45RAhigh (Naïve) T cells were sorted from HCV CORE specific CD4+ T cells from Group 1 and 2 patients incubated with either control medium or Group 3 sera. ROR-C expression was quantified using real time PCR (values represented normalized to GADPH expression). Memory cells when incubated with Group 3 sera were noted to express significantly higher ROR- C transcripts. * p value <0.05, ** p<0.01

CD3+CD4+CD45ROhighCD45RA-(Memory) and CD3+CD4+CD45RO-CD45RAhigh (Naïve) T cells were sorted from HCV CORE specific CD4+ T cells from both Group 1 and 2 patients. They were incubated with either control medium or Group 3 sera and evaluated for retinoic acid related orphan receptor (ROR-C) expression by quantitative real time PCR. CD4+CD45ROhighCD45RA-memory T cells which secreted IL-17 in response to HCV CORE following incubation with Group 3 sera significantly over-expressed ROR-C transcripts compared to CD4+memory T cells derived from control sera and CD45RAhigh CD45RO-T cells (Figure 5C). Addition of either anti-IL-6 or anti- IL1-β to cultures incubated in Group 3 sera reduced frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells in both Group 1 and 2 patients by 15.6±3.2% and 16.2±2.9% respectively (Figure 6). Combined blockade of IL-6 and IL-1β decreased frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells by 37.4±4.6% (p<0.01) than either alone, indicating the synergistic role for IL-6 and IL-1β in the induction of HCV specific Th17 cells. In contrast, cultures treated with anti-IFN-γ which were incubated in Group 3 sera demonstrated a 30.5±4.2% increase (anti-IFN-γ: 65±8, Isotype: 41±11 spm, p<0.01) in frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells compared to cultures treated with isotype control. Addition of anti-IFN-γ increased frequency of HCV specific Th17 cells in cultures treated with anti-IL-6, anti-IL1β or both by 10.5±1.7%, 12.3±2.4%, and 14.2±3.8%, respectively.

Figure 6. IFN-γ down modulates and IL-6, IL-1β synergistically promote the induction of HCV specific Th17 cells in OLT recipients with HCV recurrence.

Frequency of HCV CORE specific CD4+ T cells secreting IL-17 induced in vitro was evaluated using ELISpot following neutralization of IFN-γ or IL-6 or IL-1β bioactivity by addition of appropriate mAbs (10μg/mL) to cultures incubated with pooled Group 3 sera (filled boxes) or 25% autologous or normal AB negative sera was used as a control (open boxes). Values represented as mean ± SEM. Neutralization of IL-6 or -IL1β reduced the frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells by 15.6±3.2% and 16.2±2.9% respectively. Combined blockade of IL-6 and IL-1β decreased the frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells by 37.4±4.6% (p<0.01) than either alone. Neutralization of IFN-γ demonstrated a 30.5±4.2% (p<0.01) increase in the frequency of HCV CORE specific Th17 cells compared to cultures treated with isotype control Abs. ** p value <0.01

Discussion

Immune status of the OLTr is a critical determinant of graft prognosis (28) and greater than 10% of OLTr may require re-transplantation due to recurrent HCV induced allograft cirrhosis (29). We analyzed frequency of CD4+ T cells specific to HCV structural and nonstructural antigens secreting IL-17, IFN-γ and IL-10 in 51 OLTr with recurrent HCV and 24 controls. Frequencies of CD4+Th17 secreting IL-17 to HCV antigens were significantly increased in OLTr with high grade allograft inflammation and fibrosis/cirrhosis. Increased frequencies of HCV specific Th17 cells and serum IL-17 in these patients was associated with decreased IFN-γ dependent Th1 immunity and increased levels of Th2 cytokines: IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10. These patients also demonstrated elevated levels of cytokines IL-17, IL-6, IL-1β and chemokines IL-8 and MCP-1. Our results extend previous findings of increased IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1β in patients with hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in chronic HCV infection. (22–26).

Development of predominant CD4+Th17 immunity specific to HCV antigens was associated with a lack of optimal CD4+Th1 and increased CD4+Th2 immunity to the virus (Table 2, Figures 1–3). IL-10, a Th2 cytokine, is an important regulator of HCV specific CD4+ T cells that secrete IFN-γ (30). The predominant IL-10 dependent Th2 immunity in OLTr who concurrently demonstrate lack of Th1 immunity suggests that the expansion of IL-10 secreting CD4+T cells is HCV induced. Furthermore, IL-10 mediated inhibition of IFN-γ may represent an important mechanism of immune evasion during HCV recurrence that may lead to allograft cirrhosis (31). We also found that a subset of OLTr (Group 3) demonstrated expansion of HCV specific CD4+ T cells that secrete IL-10 and IL-17. Although neutralization of IL-10 in vitro significantly enhanced frequency of HCV CORE specific INF-γ secreting Th1 cells, frequency of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells remained unaltered (Figure 5). This suggests that HCV induced IL-10 down regulates IFN-γ but has no effect on IL-17 production from HCV specific CD4+ T cells in OLTr with HCV recurrence.

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs, are important for regulation of HCV specific CD4+ T helper cells (32). HCV can alter the frequency of Foxp3+Treg population in intrahepatic and peripheral sites, which is an important immune evasion mechanism (33). We found significantly increased frequency of Tregs in OLTr with HCV recurrence compared to either non HCV OLTr or normal subjects (Figure 4). Patients with severe fibrosis (Groups 2 and 3) had higher number of Tregs compared to Group 1. These results support previous findings demonstrating increased expression of Foxp3 in the allograft following OLT in recurrent HCV (34). Furthermore, addition of Tregs to HCV specific CD4+ T cells derived from OLTr significantly dampened IFN-γ but not IL-17 secretion (Figure 3B). This inability of Tregs to suppress HCV specific Th17 cells was also seen in non transplanted chronic HCV patients (Figure 3D). Thus, HCV infection may alter the immune status in both chronic HCV patients as well as post OLT by promoting expansion of CD4+ T cells with a regulatory phenotype which preferentially inhibit IFN-γ but not IL-17.

Serum IFN-γ and frequency of HCV specific Th1 cells negatively correlate with serum IL-17 and HCV specific Th17 cells respectively, raising the possibility that IFN-γ may negatively regulate the induction of HCV specific Th17 cells. This is also suggested by data that T-bet, the transcriptional factor for CD4+Th1 cells, has a protective role in diseases by limiting development Th17 cells (35, 36). Serum levels of IL-6 and IL-1β were significantly elevated in OLTr with HCV recurrence compared to non HCV and controls. We identified a synergistic role for IL-6 and IL-1β in induction of HCV specific Th17 cells as combined blockade of IL-6 and IL-1β decreased frequency of HCV specific Th17 cells in vitro by 37.4+4.6% (p<0.01) than either alone. Neutralization of IFN-γ augmented the frequency of HCV specific Th17 cells in vitro. This suggests that IFN-γ negatively regulates while IL-6 and IL-1β promote induction of HCV specific CD4+Th17 cells in OLTr with recurrent HCV (Figure 5).

A limitation of our study is the lack of evaluation of intrahepatic T lymphocyte (IHL) responses to HCV. Isolating adequate numbers of lymphocytes from small biopsies to perform in vitro studies without culture is not feasible. Although numerous approaches have been attempted to isolate IHLs by magnetic micro beads and culture (37), these are not standardized, often resulting in skewed T cell responses. Another limitation is that the study is not prospective due to unavailability of serial samples.

In conclusion, results presented in this study demonstrate that induction of HCV specific Th17 cells play an important role in immunopathogenesis of increased necroinflammatory activity and fibrosis following OLT in HCV patients. Suppression of IFN-γ activity due to increased Tregs in conjunction with the increased levels of IL-6 and IL-1β by HCV facilitates induction of HCV specific CD4+Th17 in OLTr leading to enhanced allograft inflammation and cirrhosis. HCV specific Th17 cells may represent an important therapeutic target to improve allograft function in OLTr with recurrent HCV.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Billie Glasscock for her assistance in preparing this manuscript and Lili Wang, MD, MS for her valuable support on statistical analyses.

Funding Source: This publication was made possible by an award from the NIH DK065982 (TM), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. AS and DSN were supported by 5-T32-DK07301-35 and NIH Training Grant T32 HL07776 respectively. TM is supported by the BJC Foundation.

References

- 1.Wright TL, Donegan E, Hsu HH, Ferrell L, Lake JR, Kim M, et al. Recurrent and acquired hepatitis C viral infection in liver transplant recipients. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(1):317–322. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91129-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenguer M, Lopez-Labrador FX, Wright TL. Hepatitis C and liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;35(5):666–678. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari C, Valli A, Galati L, Penna A, Scaccaglia P, Giuberti T, et al. T-cell response to structural and nonstructural hepatitis C virus antigens in persistent and self-limited hepatitis C virus infections. Hepatology. 1994;19(2):286–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sreenarasimhaiah J, Jaramillo A, Crippin J, Lisker-Melman M, Chapman WC, Mohanakumar T. Lack of optimal T-cell reactivity against the hepatitis C virus is associated with the development of fibrosis/cirrhosis during chronic hepatitis. Hum Immunol. 2003;64(2):224–230. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang KM, Thimme R, Melpolder JJ, Oldach D, Pemberton J, Moorhead-Loudis J, et al. Differential CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell responsiveness in hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):267–276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wedemeyer H, He XS, Nascimbeni M, Davis AR, Greenberg HB, Hoofnagle JH, et al. Impaired effector function of hepatitis C virus-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Immunol. 2002;169(6):3447–3458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruener NH, Lechner F, Jung MC, Diepolder H, Gerlach T, Lauer G, et al. Sustained dysfunction of antiviral CD8+ T lymphocytes after infection with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2001;75(12):5550–5558. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5550-5558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas M, Ulsenheimer A, Pfafferot K, Heeg MH, Gaudieri S, Gruner N, et al. Tracking virus-specific CD4+ T cells during and after acute hepatitis C virus infection. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semmo N, Klenerman P. CD4+ T cell responses in hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(36):4831–4838. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman AJ, Marinos G, Ffrench RA, Lloyd AR. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis C virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2001;79(6):515–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassoba H, Leheta O, Sayed A, Fahmy H, Fathy A, Abbas F, et al. IL-10 and IL-12p40 in Egyptian patients with HCV-related chronic liver disease. Egypt J Immunol. 2003;10(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobue S, Nomura T, Ishikawa T, Ito S, Saso K, Ohara H, et al. Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles and their relationship to clinical features in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(8):544–551. doi: 10.1007/s005350170057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharat A, Barros F, Narayanan K, Borg B, Lisker-Melman M, Shenoy S, et al. Characterization of virus-specific T-cell immunity in liver allograft recipients with HCV-induced cirrhosis. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(6):1214–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemmers A, Moreno C, Gustot T, Marechal R, Degre D, Demetter P, et al. The interleukin-17 pathway is involved in human alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):646–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.22680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang JY, Zhang Z, Lin F, Zou ZS, Xu RN, Jin L, et al. Interleukin-17-producing CD4(+) T cells increase with severity of liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009 doi: 10.1002/hep.23273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harada K, Shimoda S, Sato Y, Isse K, Ikeda H, Nakanuma Y. Periductal interleukin-17 production in association with biliary innate immunity contributes to the pathogenesis of cholangiopathy in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(2):261–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03947.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radstake TR, van Bon L, Broen J, Hussiani A, Hesselstrand R, Wuttge DM, et al. The pronounced Th17 profile in systemic sclerosis (SSc) together with intracellular expression of TGFbeta and IFNgamma distinguishes SSc phenotypes. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen W, Durum SK. Synergy of IL-23 and Th17 Cytokines: New Light on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Neurochem Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabrega E, Lopez-Hoyos M, San Segundo D, Casafont F, Pons-Romero F. Changes in the serum levels of interleukin-17/interleukin-23 during acute rejection in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(6):629–633. doi: 10.1002/lt.21724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):888–898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng W, Li W, Liu W, Wang F, Li Y, Yan W. IL-17 induces myocardial fibrosis and enhances RANKL/OPG and MMP/TIMP signaling in isoproterenol-induced heart failure. Exp Mol Pathol. 2009;87(3):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonelli A, Ferri C, Ferrari SM, Ghiri E, Marchi S, Colaci M, et al. High interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha serum levels in hepatitis C infection associated or not with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28(10):1179–1185. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang YS, Hwang SJ, Chan CY, Wu JC, Chao Y, Chang FY, et al. Serum levels of cytokines in hepatitis C-related liver disease: a longitudinal study. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1999;62(6):327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyanagi Y, Takahashi T, Matsui S, Takahashi S, Boku S, Takahashi K, et al. Enhanced expression of interleukin-6 in chronic hepatitis C. Liver. 1999;19(6):464–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali MA, Koura BA, el-Mashad N, Zaghloul MH. The Bcl-2 and TGF-beta1 levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Egypt J Immunol. 2004;11(1):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bortolami M, Kotsafti A, Cardin R, Farinati F. Fas/FasL system, IL-1beta expression and apoptosis in chronic HBV and HCV liver disease. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15(7):515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayyoub M, Deknuydt F, Raimbaud I, Dousset C, Leveque L, Bioley G, et al. Human memory FOXP3+ Tregs secrete IL-17 ex vivo and constitutively express the T(H)17 lineage-specific transcription factor RORgamma t. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(21):8635–8640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900621106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruener NH, Jung MC, Schirren CA. Recurrent hepatitis C virus infection after liver transplantation: natural course, therapeutic approach and possible mechanisms of viral control. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54(1):17–20. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forman LM. To transplant or not to transplant recurrent hepatitis C and liver failure. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7(3):615–629. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piazzolla G, Tortorella C, Schiraldi O, Antonaci S. Relationship between interferon-gamma, interleukin-10, and interleukin-12 production in chronic hepatitis C and in vitro effects of interferon-alpha. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20:54–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1006694627907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett L, Gallant M, Howley C, Bowmer MI, Hirsch G, Peltekian K. Enhanced IL-10 production in response to hepatitis C virus proteins by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus-monoinfected individuals. BMC Immunol. 2008;28:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bolacchi F, Sinistro A, Ciaprini C, Demin F, Capozzi M, Carducci FC, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV)-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T lymphocytes and reduced HCV-specific CD4+ T cell response in HCV-infected patients with normal versus abnormal alanine aminotransferase levels. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144(2):188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manigold T, Shin EC, Mizukoshi E, Mihalik K, Murthy KK, Rice CM, et al. Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ T cells control virus-specific memory T cells in chimpanzees that recovered from hepatitis C. Blood. 2006;107(11):4424–4432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demirkiran A, Baan CC, Kok A, Metcelaar HJ, Tilanus HW, van der Laan LJ. Intrahepatic detection of FOXP3 gene expression after liver transplantation using minimally invasive aspiration biopsy. Transplantation. 2007;83:819–823. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258597.97468.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutitzky LI, Smith PM, Stadecker MJ. T-bet protects against exacerbation of schistosome egg-induced immunopathology by regulating Th17-mediated inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(9):2470–2481. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan X, Paez-Cortez J, Schmitt-Knosalla I, D’Addio F, Mfarrej B, Donnarumma M, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):3133–3144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morsy MA, Norman PJ, Mitry R, Rela M, Heaton ND, Vaughan RW. Isolation, purification and flow cytometric analysis of human intrahepatic lymphocytes using an improved technique. Lab Invest. 2005;85(2):285–296. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]