Health care in America is always making news. Rising costs, uneven quality, and limited access are the grist of headline after headline. And beyond these core issues, stories about fraud and abuse, drug and device recalls, and medical malpractice bob up to the front page nearly as often.

A solution to these ills has become a sort of Riemann Hypothesis for public policy analysts and everyone—management professors like Michael Porter and Regina Herzlinger, politicians such as Newt Gingrich and Hillary Clinton, businessmen like Steve Case—is pitching in with suggestions.

These and many other earnest, smart and creative people have offered answers—pay-for-performance, focused factories, electronic medical records, chronic disease management, preventive medicine and wellness, consumer-directed health plans and many others.

As health professionals know all too well, despite the best of intentions, these strategies will only yield some of the answers. The daunting issues facing American medicine won't be solved with a sudden stroke of genius but rather it will require tough decisions and sacrifice by all following a national debate about priorities. And rather than the marketplace, many of these decisions must be made in the political arena, probably after some historic battles.

As they gird themselves for these confrontations, where do the politicians stand? When faced with such problems, most will turn for advice and counsel to those steadiest of friends—the public opinion polls—with some predictable questions.

What is the public say in these debates? Where do they stand on rising health care costs? What is America's commitment to the uninsured? What's their take on uneven quality and patient safety?

There is certainly no shortage of organizations glad to offer their help, either supporting or conducting polls—nonprofits such as the Commonwealth Fund, Public Agenda, Kaiser Family Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Center for Studying Health System Change; universities like Chicago, Quinnipiac, the Roper Center at the University of Connecticut; private concerns such as Lake Snell Perry, Mathematica, the Gallup and Harris Polls; and the press including the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, USA Today and television networks.

Not surprisingly, from 35,000 feet, the polling results don't look so good at this point. Compared with five other public issues, health care, at 34% satisfaction, is viewed the most negatively (the Constitutional system—77%; overall quality of life—77%; present government—54%; economy—54%; environment—51%). Americans even view the Canadian health care system better than their own (34% vs 49%).1

Drilling down a bit, between costs, access and quality, concerns about costs generally predominate. In response to the question “Are you generally satisfied or dissatisfied with the total cost of health care in this country?,” 78% of Americans expressed dissatisfaction, compared with satisfaction in 21%.2

In a 2005 study by the nonpartisan Public Agenda, only the war in Iraq (51%), terrorism (49%), and education (44%) had higher ratings of extreme importance than health care costs (42%).3

Improving access by increasing health insurance coverage is regarded as very important by 79% of the public (exceeded only by lowering costs at 82%). Nearly 60% worry a great deal about providing insurance for those Americans who cannot afford it. More than 80% support requiring businesses to provide insurance, expanding government programs such as Medicaid, and increasing government support of community health programs.4

Since the 1999 Institute of Medicine report, Too Err is Human,5 the public has been much more attuned to the issue of quality and patient safety. A 2002 study in Colorado found an overwhelming majority had concerns about quality, the lack of attention paid to safety and the absence of a reporting system.6

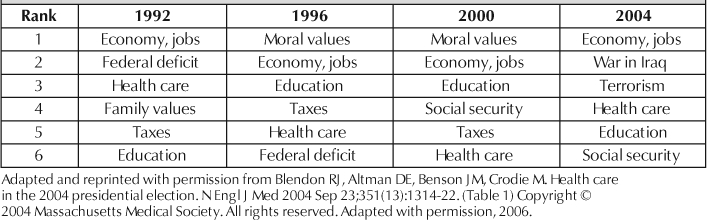

As informative as these polls are, there are many caveats in interpreting these data. First, unexpected political and economic events can change things in a hurry. In Table 1, two new factors in electoral decision making emerged between 2000 and 2004.7 Because of the attacks of September 11, 2001, terrorism and the war in Iraq understandably rose to the top of public concerns, and resources, both tangible and emotional, had to be diverted from social programs to national defense.

Table 1.

Issues for voters in 1992, 1996, 2000, 2004 Presidential elections

Public opinion can also be quickly swayed by advertising or derogatory publicity. In 1950, in less than 18 months, opposition to President Truman's national health insurance plan grew from 38% to 61% because of fierce lobbying. As a result of the negative “Harry-and-Louise” ads and other lobbying attacks in 1994, support for President Clinton's health proposal dwindled from 59% to 40% in barely a year.8

The public's perception of health threats also changes, often dramatically. For instance, in 1999, AIDS was viewed as the nation's number one health problem, identified so by a third of the population. Five years later, it was considered that important by only 5% of Americans, well behind costs, access, cancer and obesity.9 On occasion, the public's opinion is contradictory. In a Kaiser/Harvard poll in 2005, half of the respondents believed that the government was not doing enough to ensure the safety of pharmaceuticals, but 80% thought that prescription drugs were safe.4

The wording of a question, frequently not reported in a news sound bite, can make all the difference in the response. Consider the following example:

Which would you prefer: the current health insurance system in the US in which most people get their health insurance from private employers, but some have no insurance, or a universal health insurance program in which everyone is covered under a system like Medicare that's run by the government and financed by taxpayers?

Sixty-two percent respond with universal coverage.

Would you favor or oppose a national health plan, financed by taxpayers, in which all Americans would get their insurance from a single government plan?

Fifty-five percent oppose the plan.10 Polling is also confounded by the complexity of medical care with its intricate science and arcane language. For instance, the public has expressed little concern about infectious diseases as a health problem, but regards ebola, mad cow disease, and West Nile virus as major worries.11

Finally, the one issue that is difficult to tease out of the polling is a unique type of selection bias. That is, while the polls carefully select a representative sample of the general population, this group may have a skewed view of health care. For example, 5% of the public consume 50% of health care dollars annually with the other half spread out among the healthier 95%.12 Is it realistic to think that the healthy half is as experienced as their unhealthy neighbors? As concerned about costs? Disturbed by poor quality?

Although 5% consume half of health care resources, one in five Americans spends nothing annually for medical care. When polled, suppose all of the unhealthy 5% believed that the quality of health care was terrible, the costs outrageous and access wretched. And the 20% who spent nothing thought everything was fine. That would mean that four times more Americans were satisfied than dissatisfied, but would this be an accurate reflection of the status of health care?

Despite these shortcomings of public polls, over the long term, truisms emerge. One is the declining faith of the people in the government's ability to solve complex social problems. From 1958 to 2000, the percentage of those who trusted Washington to do what is right only some or none of the time rose from 23% to 69%.7

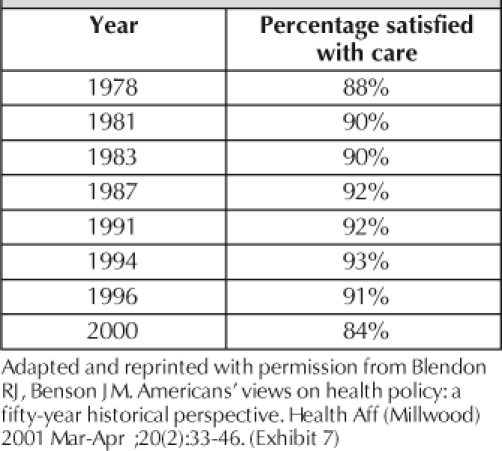

Another touchstone is the enduring public faith in individual physicians and hospitals. For all the foibles of medicine, Americans still steadily hold both in high regard with 84%-93% expressing satisfaction with their own personal medical care (Table 2).7

Table 2.

American's satisfaction with their own medical care, 1978-2000

Finally, how much has public opinion really changed? How much of the debate is strum und drang generated by the press, or a genuine groundswell of public opinion that will precipitate real change?

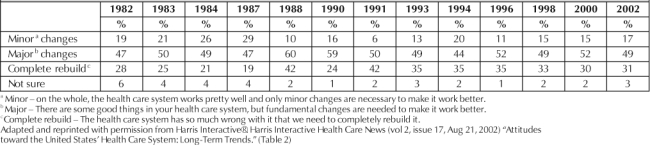

For more than half a century, medical care has been the focus of tumultuous politics, starting with the controversy surrounding President Truman's initial proposal for national health insurance in 1945; the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965; Nixon's mandatory insurance plan of 1970; Clinton's Health Security Act in 1994. Yet in many ways the public's view remains remarkably stable (Table 3). Annual surveys of public attitudes about total health spending between 1973 and 1998 found that those who believed the spending was “too much” varied only from 2% to 5%.13

Table 3.

Public attitudes toward health care system, selected years, 1982-2002

Much to their dismay and peril, policymakers, rather than having a clear public mandate, may have a fuzzy dashboard while confronting these difficult issues.

Footnotes

Michael J Pentecost, MD, is a member of the Permanente Medical Group of the Mid-Atlantic States. This article is reprinted and adapted from his November 2005 “Washington Watch” column in the Journal of the American College of Radiology with permission. The views expressed here are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of The Permanente Journal or the MAPMG.

References

- Harris Interactive. Americans rate Canadian health care better than US system. Health Care News [serial on the Internet] 2004 Aug 30 [cited 2006 Jan 11];4(14) [about 3 p]. Available from: www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters_healthcare.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda.org [homepage on the Internet] New York: Public Agenda; 2005 [cited 2006 Jan 24]. Health care: people' s chief concerns: Most Americans say they are dissatisfied with the overall cost of health care in the US, but more than half say they are satisfied with what they personally pay; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.publicagenda.org/issues/pcc_detail.cfm?issue_type=healthcare&list=3. [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda.org [homepage on the Internet] New York: Public Agenda; 2005 [cited 2006 Jan 24]. Health care: people' s chief concerns: Most Americans say health care costs should be a high legislative priority in 2005; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.publicagenda.org/issues/pcc_detail.cfm?issue_type=healthcare&list=2. [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda.org [homepage on the Internet] New York: Public Agenda; 2005 [cited 2006 Jan 24]. Health care: red flags; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.publicagenda.org/issues/red_flags_detail.cfm?issue_type=healthcare&list=2&area=1. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To err is human: Building a safer health system [monograph on the Internet] In: Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2000 [cited 2005 Feb 23]. Available from: www.nap.edu/openbook/0309068371/html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AR, Hohmann KB, Rifkin JI, et al. Physician and public opinion on quality of health care and the problem of medical errors. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Oct 28;162(19):2186–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Altman DE, Benson JM, Brodie M. Health care in the 2004 presidential election. New Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1314–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa042360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Americans' views on health policy: a fifty-year historical perspective. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001 Mar–Apr;20(2):33–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda.org [homepage on the Internet] New York: Public Agenda; 2005 [cited 2006 Jan 24]. Health care: people' s chief concerns: Cost and access to health care are the most urgent health problems in the eyes of the public, compared to 1999 when AIDS and cancer topped the list; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.publicagenda.org/issues/pcc_detail.cfm?issue_type=healthcare&list=1. [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda.org [homepage on the Internet] New York: Public Agenda; 2005 [cited 2006 Jan 24]. Health care: red flags: Support for a health plan covering all Americans and financed by taxpayers can vary depending on question wording; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.publicagenda.org/issues/red_flags_detail.cfm?issue_type=healthcare&list=4&area=2. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon RJ, Scoles K, DesRoches C, et al. Americans' health priorities: curing cancer and controlling costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001 Nov–Dec;20(6):222–32. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorson GC. Commentary—Current MSA theory: well-meaning but futile. Health Serv Res. 2004 Aug;39(4 Pt 2):1119–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Interactive. Attitudes toward the United States' health care system: Longterm trends. Health Care News [serial on the Internet] 2004 Aug 21 [cited 2006 Jan 11];2(17) [about 6 p]. Available from: www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters_healthcare.asp. [Google Scholar]