Abstract

Salicylic acid (SA) is a critical hormone for signaling innate immunity in plants. Here we present the purification and characterization of SA-binding protein 2 (SABP2), a tobacco protein that is present in low abundance and specifically binds SA with high affinity. Sequence analysis predicted that SABP2 is a lipase belonging to the α/β fold hydrolase super family. Confirming this prediction, recombinant SABP2 exhibited lipase activity against several synthetic substrates. Moreover, this lipase activity was stimulated by SA binding and may generate a lipid-derived signal. Silencing of SABP2 expression suppressed local resistance to tobacco mosaic virus, induction of pathogenesis-related 1 (PR-1) gene expression by SA, and development of systemic acquired resistance. Together, these results suggest that SABP2 is an SA receptor that is required for the plant immune response. We further propose that SABP2 belongs to a large class of ligand-stimulated hydrolases involved in stress hormone-mediated signal transduction.

Mounting evidence suggests that the innate immune system of plants shares many parallels with that of vertebrates and insects (1-3). In plants, the ability to recognize a pathogen and activate an effective defense is often governed by an interaction (direct or indirect) between the products of a plant resistance gene and a pathogen avirulence gene (4, 5). After this gene-forgene interaction, the inoculated leaves may exhibit ion fluxes, the production of reactive oxygen species, salicylic acid (SA), nitric oxide, and increased expression of defense-associated genes, including those encoding pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins (1, 6, 7). In addition, the cells surrounding the site(s) of pathogen entry usually undergo apoptotic-like cell death, thereby forming the necrotic lesions characteristic of the hypersensitive response (8, 9). Generally, the pathogen is restricted to these lesions. Subsequent to the local responses, plants frequently develop a broad-based long-lasting resistance to secondary pathogen infection known as systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Concurrent with SAR development, the systemic leaves accumulate SA and PR gene transcripts. The correlation between PR gene expression and systemic resistance makes these genes excellent markers for SAR.

Many studies have demonstrated that SA is a critical signal for the activation of both local and systemic resistance responses. For example, tobacco and Arabidopsis plants that are SA-deficient or are unable to accumulate SA after infection fail to develop SAR, do not express PR genes in the uninoculated leaves, and display enhanced susceptibility to pathogen infection (7, 10-12). Recent evidence suggests that SA also regulates cell death, possibly via a positive feedback loop that involves reactive oxygen species (13-15). Additionally, SA cross regulates the ethylene and jasmonic acid-dependent defense pathways (12, 16).

To investigate how SA exerts its effects, several putative effector proteins have been identified, including catalase (17, 18), ascorbate peroxidase (19), and carbonic anhydrase (20). All three bind SA with low to moderate affinity (Kd of 14-3.7 μM) and appear to have antioxidant activity. In comparison, SA-binding protein 2 (SABP2) was identified as a very low-abundance (10 fmol/mg) soluble protein of ≈25 kDa that exhibits high affinity for SA (Kd = 90 nM) (21). This binding was reversible and specific to SA and its SAR-inducing analogs. Here we report the purification of SABP2 and cloning of its encoding gene. Furthermore, we demonstrate that SABP2 has SA-stimulated lipase activity and that SABP2 is required for full local and systemic resistance to pathogen infection.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material, Pathogen Infection, and Chemical Treatments. All plants were grown and inoculated with tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), as described (22). Induction of PR-1 expression was performed by infiltrating leaves with 0.25 mM SA (pH 7.0).

Purification of Tobacco SABP2. Fully expanded leaves from 7- to 8-wk-old tobacco plants were powderized in liquid N2 and homogenized in 3 vol (wt/vol) of buffer A [20 mM sodium citrate/5 mM MgSO4/1 mM EDTA, pH 6.3/14 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylflouride (PMSF)/1mM benzamidine-HCl] with 1.5% (wt/wt) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone. The homogenate was filtered and then centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant was fractionated by ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2SO4] precipitation, as described (21). The 50-75% fraction was applied to a Sephadex G-100 column [Amersham Pharmacia (AP)] in buffer A. Fractions with high [3H]SA-binding activity were concentrated by precipitation with 75% (NH4)2SO4. Further chromatographic steps were carried out by using a FPLC system (AP). The concentrated protein from Sephadex G-100 step was resuspended and desalted by using buffer B (10 mM bicine, pH 8.5/14 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1 mM PMSF/1 mM benzamidine-HCl) and applied to a Q Sepharose column (AP) preequilibrated with buffer B. The bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 15-180 mM (NH4)2SO4 in buffer B. To the fractions with high [3H]SA-binding activity, (NH4)2SO4 was added to a concentration of 1 M and applied to a Butyl Sepharose column (AP) preequilibrated with 1.2 M (NH4)2SO4 in buffer B. The bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of decreasing (NH4)2SO4 (1-0 M). The fractions with high binding activity were again concentrated, desalted, and applied to a Mono Q column (HR 5/5, AP). The bound proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 15-180 mM (NH4)2SO4 in buffer B. Fractions with high binding activity were concentrated, desalted, and loaded onto a Superdex 75 column (HR 10/30, AP), preequilibrated with buffer C (buffer B plus 150 mM [NH4]2SO4). The proteins were eluted with buffer C. Fractions containing high binding activity were further purified on a Mono Q column after concentration and desalting in buffer B.

SA Binding, Protein Estimation, and SDS/PAGE Analysis. SA binding, in the absence or presence of its analogs, was measured as described (20, 21). Protein concentration was determined by Bradford analysis, and SDS/PAGE analysis was performed on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels by using Laemmli's protocol followed by Coomassie blue R-250 or silver staining to visualize the proteins.

Amino Acid Sequencing. Fractions from the second Mono Q column containing peak [3H]SA-binding activity were separated by SDS/PAGE and stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue R-250. The protein bands that copurified with SA-binding activity were excised and sequenced at the Biotechnology Resource Center, Cornell University, after in-gel digestion with trypsin.

Cloning SABP2, Sequence Alignments, and Database Searches. Based on the amino acid sequences of the tryptic peptides, several degenerate oligonucleotides were custom synthesized (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from DNase-treated total RNA extracted from young leaves by using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and the universal oligo-dT(14) with an adapter sequence. A combination of degenerate primer ACWCARTTYTTRCCHTAYGG (W, A or T; R, A or G; Y, C or T; H, A, C, or T), and the universal adapter primer (GACTCGAGTCGACATCGA) was used to PCR amplify the SABP2 cDNA. The amplified products were cloned into pGEMT (Promega), and several independent clones were sequenced and analyzed. The full-length SABP2 gene was cloned by performing 5′ RACE by using the SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech). Sequence comparisons were carried out with the dna star software (DNAstar, Madison, WI). Multisequence alignments were constructed with the clustalw program of the European Bioinformatics Institute, and database searches were performed with the blast program from National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Expression of Recombinant SABP2 (rSABP2) in Escherichia coli. Full-length tobacco SABP2 was PCR amplified to introduce BamH1 enzyme sites at both ends by using the primers F2 (CGCGGATCCATGAAGGAAGGAAAACACTTTG) and F3 (GCGGGATCCAGATCAGTTGTATTTATGGGC). The amplified product was cloned into the BamH1 site of pET28a (Novagen) and sequenced. rSABP2 was synthesized as a soluble protein in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) and affinity purified by Ni-NTA agarose chromatography (Novagen) as described by the manufacturer. rSABP2 was further purified on a Mono Q column as described earlier.

Lipase Activity Assay. The lipase activity assay was performed as described (23) with modifications to allow SA binding to SABP2. The standard 1-ml assay mixture consisted of 1 mM substrate in 50 mM bicine, pH 8.0, 0.05% Triton X-100. After a 60-min preincubation on ice in the absence or presence of 1 mM SA, the reaction was allowed to proceed at 24°C for 60 min. A 100 mM stock solution of para-nitrophenyl myristate (p-NPM) or para-nitrophenyl palmitate (pNPP) was prepared in acetonitrile. Lipase activity was estimated colorimetrically (Unicom UV1, Spectronic Unicom, Cambridge, U.K.) by measuring the liberation of para-nitrophenol from p-NPP or p-NPM at 410 nm. Measurements from control reactions without SABP2 were subtracted from each reaction. For non SA-binding conditions, Tris·HCl, pH 8.0 (50 mM), was used in place of bicine buffer.

Plasmid Construction and Plant Transformation. The RNAi-SABP2 construct was made in the pHANNIBAL vector (24) by inserting a 404-bp fragment corresponding to the 5′ portion of SABP2. The fragment corresponding to the sense arm of the hairpin loop was generated by using the primers F6 (CCGCTCGAGATGAAGGAAGGAAAACACTTG) and F7 (GGGGTACCAGATCAGTTGTATTTATGGGC) and cloned in the XhoI-KpnI site. The fragment for the antisense arm was generated by using the primers F2 and G2 (GCGGGATCCCTGAGTATCCAACCAATTCTCGG) and was cloned into the BamH1 site. The NotI fragment from pHANNIBAL containing SABP2 was then subcloned into binary vector pART27 and transformed into Agrobacterium strain LBA4404. Plant transformations and regeneration and maintenance of the transgenic lines were carried out as described (25).

RNA Blot Analysis and RT-PCR Analysis. Total RNA was extracted from tobacco leaves as described in ref. 26. Ten micrograms of total RNA per lane was used for RNA blot analyses. Blots were hybridized with desired probes as specified in Figs. 4 and 5 legends. Hybridizations were carried out as described (27) and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen.

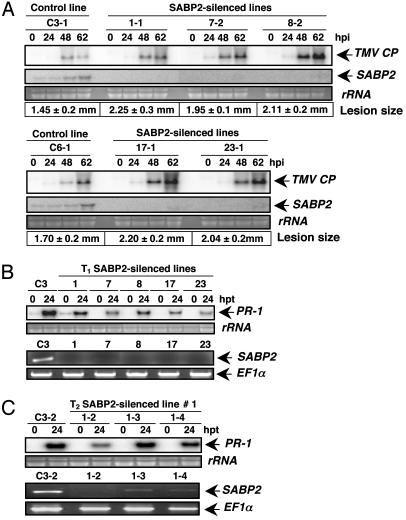

Fig. 4.

Silencing of SABP2 suppresses local resistance to TMV and SA-induced PR-1 expression. (A) RNA blot analysis of TMV CP and SABP2 transcript accumulation in control plants (transformed with empty vector) and various SABP2-silenced lines from the T2 generation. Total RNA was isolated from TMV-inoculated leaves harvested at the indicated time points. After transfer, the membrane was hybridized with probes for the SABP2 and TMV CP. The size of TMV-induced lesions presented is an average of 50 lesions per line. Lesion diameter is presented ± standard deviation. (B) Comparison of SA-induced PR-1 expression and SABP2 silencing in the T1 generations of control and SABP2-silenced lines. Total RNA was isolated from all lines at 0 and 24 h posttreatment (hpt) with 0.25 mM SA. PR-1 expression was monitored by RNA blot analysis, whereas SABP2 expression was determined by RT-PCR analysis by using cDNA generated from untreated plants. The level of EF1α product was monitored as an internal control to normalize the amount of cDNA template. Please note that PR-1 induction by SA was tested at least twice in two independent experiments for both the T1 and T2 generations to confirm the difference in SA responsiveness. (C) Comparison of SA-induced PR-1 expression and SABP2 silencing in three different T2 generation plants for line 1; see B for details.

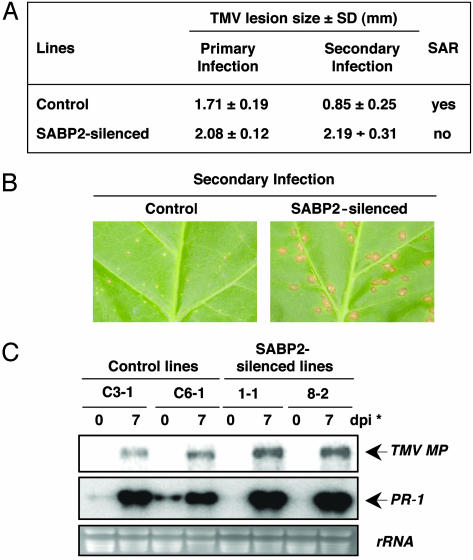

Fig. 5.

Silencing SABP2 expression blocks SAR development. (A) The size of primary lesions developed by TMV-inoculated control and SABP2-silenced plants (T2 generation) was measured at 7 dpi. Seven days after the primary TMV infection, the upper previously uninoculated leaves received a secondary inoculation with TMV. The diameter of the secondary lesions was then measured 7 days after challenge infection. Each value represents the average size (in mm ± standard deviation) of 50 lesions per line. (B) Morphology of TMV-induced lesions in control and SABP2-silenced tobacco. The leaves were photographed 7 days after secondary infection with TMV. (C) RNA blot analysis of TMV MP and PR-1 transcript accumulation in control and SABP2-silenced T2 lines. Total RNA was isolated from systemic leaves before (0 day) or 7 days after a secondary inoculation with TMV (*). After transfer, the membrane was hybridized with probes for the TMV MP and PR-1.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using 2 μg of total RNA isolated from control and silenced plants as described above. Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed by using 1 μl of the cDNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing primers G6 (TGGCCCAAAGTTCTTGGC) and E6 (AGAGATCAGTTGTATTTATG), which anneal outside the region used for silencing SABP2 expression. Control reactions to normalize RT-PCR amplifications were run with the primers derived from constitutively expressed translation elongation factor 1α (EF1α) (forward, TCACATCAACATTGTGGTCATTGGC; reverse, TTGATCTGGTCAAGAGCCTCAAG). PCR was performed for 30 cycles at 55°C annealing temperature.

Results

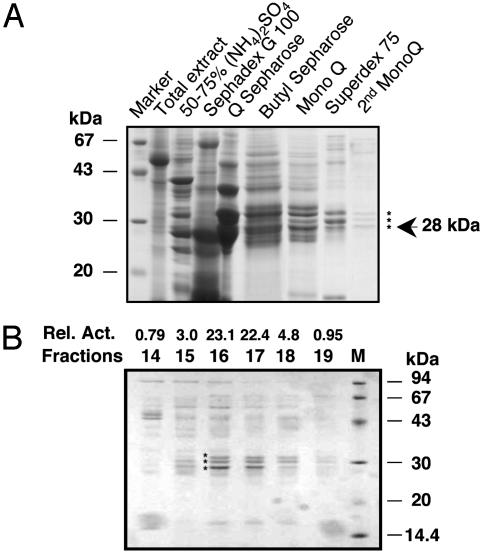

Purification of SABP2. The tobacco SA-binding activity was purified ≈24,000-fold from 7.5 kg of leaves after a seven-step protocol (Table 1). The partially purified SA-binding activity was not due to catalase (CAT) or carbonic anhydrase (CA) (SABP3), because CAT was precipitated in the 0-50% (NH4)2SO4 fractions, and CA activity eluted from the Sephadex G-100 column in different fractions from those containing SABP2.

Table 1. Purification of SABP2 from tobacco leaves.

| Fraction | Total protein, mg | Total activity, dpm | Specific activity, dpm·mg-1 | Purification, fold | Recovery, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 31,626.250 | 7,509,343 | 237 | 1.0 | 100 |

| 50–75% (NH4)2SO4 | 4,723.252 | 1,892,720 | 400 | 1.7 | 25 |

| Sephadex G-100 | 2,216.825 | 1,385,625 | 625 | 2.6 | 18.4 |

| Q Sepharose | 56.925 | 1,023,300 | 17,976 | 75.8 | 13.6 |

| Butyl Sepharose | 4.398 | 123,840 | 28,158 | 118.8 | 1.6 |

| Mono Q | 0.368 | 1,386,700 | 3,762,930 | 15,877.3 | 18.4 |

| Superdex 75 | 0.013 | 55,460 | 4,160,420 | 17,554.5 | 0.7 |

| Mono Q | 0.008 | 45,515 | 5,689,375 | 24,005.8 | 0.6 |

Analysis of fractions from the last two chromatography steps revealed three proteins of 32, 30, and 28 kDa that copurified with the SA-binding activity (Fig. 1A). Careful comparison of the prevalence of these proteins in fractions from the final Mono Q column with the level of SA-binding activity in each fraction suggested that the 28-kDa protein was SABP2 (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this conclusion, a prior purification scheme identified a 28- but not a 30- or a 32-kDa protein that copurified with SA-binding activity (data not shown). Partial amino acid sequence analysis of tryptic peptides from both 28-kDa proteins indicated that they are the same. Gel filtration chromatography also indicated that the native molecular weight of SABP2 is ≈25-30 kDa (data not shown; ref. 21). Based on this result, SABP2 appears to be a monomeric protein.

Fig. 1.

Protein profiles from the purification of tobacco SABP2. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of fractions from each step of the SABP2 purification protocol. Aliquots from pooled fractions containing peak SA-binding activity were analyzed by SDS/PAGE on a 12.5% gel that was subsequently stained with Coomassie blue. After the final Mono Q chromatography step, three proteins (indicated by *) copurifed with the SA-binding activity. An arrow marks the putative SABP2 protein, which is 28 kDa. (B) Protein profiles and SA-binding activity in fractions from the final Mono Q chromatography step. SA-binding activity (dpm, ×1,000) is shown above each fraction. The three proteins copurifying with the SA-binding activity are marked by *.

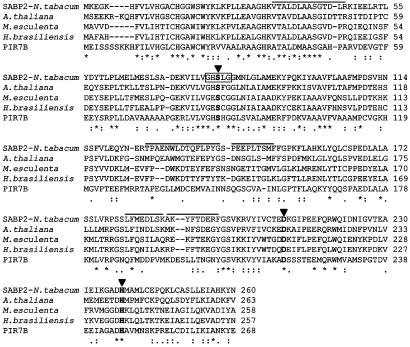

Cloning and Characterization of the SABP2 Gene. To identify the gene encoding this 28-kDa protein, RT-PCR was performed by using a degenerate primer derived from the partial amino acid sequence and a universal adapter primer. The RT-PCR-amplified 639-bp product was found to contain a complete 3′ untranslated region and a polyA tail. Using 5′ RACE, an ≈850-nt product containing the missing 5′ portion of the SABP2 gene was obtained. Combined sequence analysis of the 5′ RACE product and the original cDNA clone indicated that the SABP2 mRNA contains a single large ORF encoding a 260-aa protein with a calculated molecular mass of 29.3 kDa (Fig. 2). Sequence analysis indicates that SABP2 is a member of the α/β fold hydrolase super family, whose members contain a catalytic triad consisting of Ser, Asp, and His. SABP2 shares substantial homology to several members of this super family, including plant α-hydroxynitrile lyases and esterases. SABP2 also contains the lipase signature sequence GXSXG (amino acid residues 79-83) found in lipases belonging to this super family.

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of the tobacco SABP2 with related proteins. Aligned from top to bottom are the deduced amino acid sequences of the tobacco SABP2 and putative α-hydroxynitrile lyases (hnls) from Arabidopsis thaliana (GenBank accession no. AAO22676), Manihot esculenta (CAA11219), Hevea brasiliensis (P52704), and an esterase from Oryza sativa, Pir7b (Q43360). The residues of the catalytic triad are shown in bold and are indicated by arrowheads; the lipase signature sequence of SABP2 is boxed. The sequences corresponding to the five tryptic peptides obtained by microsequencing the 28-kDa protein are overlined. Sequence alignment was performed by using the clustalw program. The symbols used to show the degree of conservation are: *, residues identical in all sequences in the alignment;:, conserved substitutions;., semiconserved substitutions; and no symbol, nonconserved substitutions.

To rigorously establish that the 28-kDa protein purified by the seven-step protocol was SABP2, its encoding cDNA was expressed in E. coli as a His-6-tagged fusion protein. The purified rSABP2 exhibited high affinity for [3H]SA (Table 2). Moreover, this binding was effectively competed by a large molar excess of unlabeled SA or its biologically active analogs, which induce PR gene expression and resistance. By contrast, biologically inactive SA analogs were poor competitors for SA binding.

Table 2. Specificity of SA-binding activity of recombinant SABP2.

| Assay | Bound [3H]SA, dpm | Biological activity of competitor |

|---|---|---|

| rSABP2 + no competitor | 140,206 | — |

| rSABP2 + 1 mM unlabeled SA | 160 | Active |

| rSABP2 + 1 mM unlabeled 5-CSA | 260 | Active |

| rSABP2 + 1 mM unlabeled 2,6-DHBA | 924 | Active |

| rSABP2 + 1 mM unlabeled 2,5-DHBA | 90,839 | Inactive |

| rSABP2 + 1 mM unlabeled 4-HBA | 95,634 | Inactive |

5-CSA, 5-chlorosalicylic acid; 2,6-DHBA, 2,6-dihydroxybenzoic acid; 2,5-DHBA, 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid; 4-HBA, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid.

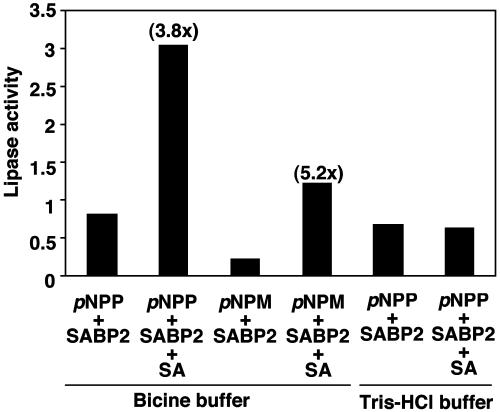

SABP2 Exhibits Lipase Activity. Because SABP2 contains the catalytic triad and the lipase signature sequence, the recombinant protein was tested for lipase activity. Highly purified rSABP2 exhibited lipase/esterase activity with 4-methylumbelliferone butyrate in an in-gel assay, and with para-nitrophenyl (pNP) butyrate in a solution assay (data not shown). rSABP2 also cleaved esters containing long carbon chains such as pNP palmitate (C-16) and pNP myristate (C-14) (Fig. 3), thereby demonstrating true lipase activity. Addition of SA to the reaction stimulated lipase activity 3- to 6-fold (Fig. 3). This stimulation required SA binding to rSABP2, because it was abolished in reaction conditions that prevented SA binding. In contrast to rSABP2, the lipase from Mucor meihei did not exhibit stimulation by SA, indicating that SA stimulation of lipase activity is not a general phenomenon (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

SA stimulates the lipase activity of recombinant SABP2. Results from lipase assays using pNP palmitate (para-nitrophenyl palmitate) as the substrate in the presence or absence of SA are presented as an average with three separate preparations of rSABP2, whereas those using pNP myristate (para-nitrophenyl myristate) as the substrate were done with one preparation of rSABP2. Lipase activity detected in each sample is presented in relative units, and fold stimulation by SA is shown in parentheses above the bars. One relative unit is the amount of enzyme that releases 0.017 μmol/min p-nitrophenol. Note that when 50 mM bicine is replaced with 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0, SABP2 does not bind SA.

SABP2 Expression Is Required for Complete Local and Systemic Resistance to TMV. To assess the role of SABP2 in defense signaling, SABP2 expression was silenced by using RNA interference (RNAi) (28). RNA blot analysis of 16 independently generated T1 lines expressing the RNAi-SABP2 construct revealed that SABP2 expression was suppressed >75% compared with the empty vector control plants (data not shown). Strikingly, the TMV-induced lesions on these plants were 41% larger than those observed on the empty vector control plants. RNA blot analysis of five independent T2 lines similarly revealed little SABP2 transcript accumulation before or after TMV infection, and the lesions were on average 34% larger than those on the control lines (Fig. 4A). Moreover, transcripts for the TMV coat protein (CP) accumulated to higher levels in the inoculated leaves of SABP2-suppressed lines as compared with control plants.

SA induction of PR-1 expression, which is associated with local resistance to TMV, was also affected in SABP2-silenced plants. Suppression of SA-induced PR-1 expression was readily detected in the T1 generation of the five lines of SABP2-silenced plants in which little, if any, SABP2 transcripts could be detected by RT-PCR under the conditions used (Fig. 4B). In the T2 generation of these five lines, the level of SABP2 silencing was more variable (Fig. 4C and data not shown). In plants in which SABP2 transcript was undetectable, SA induction of PR-1 expression was suppressed (see Fig. 4C, e.g., transgenic 1-2). However, in plants in which silencing was less effective, suppression of PR-1 induction was poor (e.g., transgenic 1-3 and 1-4). These results suggest that silencing was less effective in the T2 generation and that suppression of SA-induction of PR-1 expression depended on the level of SABP2 silencing.

Whether SAR development also is suppressed in the SABP2-silenced lines was then assessed. In control plants, the lesions formed after a secondary infection were ≈50% smaller than those produced after a primary infection (Fig. 5 A and B); this reduction in secondary lesion size is a common marker for SAR. By contrast, the lesions formed on secondarily inoculated SABP2-silenced plants were as large as those formed after a primary infection and 2.5-fold larger than those exhibited by control plants. SABP2-silenced plants also exhibited increased viral replication, as indicated by higher levels of TMV movement protein (MP) transcript in the systemic leaves of SABP2-silenced plants than control plants after secondary inoculation (Fig. 5C). In addition, systemic expression of the PR-1 gene, another common marker for SAR, was reduced in SABP2-silenced plants. Unlike control plants, whose uninoculated leaves accumulated low-to-moderate levels of PR-1 transcript after a primary infection (Fig. 5C), the systemic leaves of SABP2-silenced plants contained little to no PR-1 mRNA. After a secondary infection with TMV, however, the challenge-inoculated leaves of SABP2-silenced plants accumulated more PR-1 transcripts than those of control plants.

Taken together, these results suggest that SABP2 plays a role(s) in restricting viral replication/spread in TMV-inoculated leaves, as evidenced by increased lesion size and greater accumulation of transcripts for TMV CP. They also indicate that SABP2 expression is required for systemic PR-1 expression and the characteristic reduction in lesion size and viral replication associated with SAR.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the purification, cloning, and characterization of tobacco SABP2. SABP2 is a previously undescribed member of the α/β fold hydrolase super family. This super family consists of proteins with diverse enzymatic activities that, despite limited sequence homology, share structural homology (29). The presence of a lipase signature sequence, combined with SABP2's ability to hydrolyze artificial lipase substrates, argues that this protein is a lipase. Intriguingly, SABP2's lipase activity is enhanced by the binding of SA.

Is SABP2 a Resistance-Signaling Receptor for SA? The combined observations that SABP2 binds SA with high affinity, is present in exceedingly low concentrations, and displays SA-stimulated enzymatic activity suggest that it might be a receptor for SA. Further supporting this hypothesis, local and systemic resistance in SABP2-silenced plants was disrupted at least as effectively as in SA-deficient tobacco expressing the nahG transgene. After a primary infection with TMV, the lesions formed on T1 and T2 generations of SABP2-silenced plants were on average 41% and 34% larger, respectively, than those of control plants, whereas those formed on NahG tobacco were only 23% larger on average (30). In addition, neither SABP2-silenced nor nahG-expressing plants developed SAR. Further arguing that SABP2 is an SA receptor is the reduced ability of SA to induce PR-1 expression in plants effectively silenced for SABP2. Interestingly, SABP2 silencing was more variable and generally less effective in T2 vs. T1 plants. Less effective silencing of SABP2 correlated with poor suppression of PR-1 induction, suggesting that the residual SABP2 level in these T2 plants is at or above a threshold required for SA induction of PR-1, whereas in the T1 plants and a minority of T2 plants (e.g., transgenic 1-2 in Fig. 4C), it is below this level. Because local and systemic resistance was impaired in all T2 plants tested, the level of SABP2 required for resistance appears to be higher than that needed for PR-1 gene activation. However, the efficiency of SABP2 silencing did appear to influence how severely resistance was impaired, because the primary TMV lesions on T2 plants were not as large as those on T1 plants.

The reduction in local resistance, inability to activate SAR, and loss of SA responsiveness exhibited by SABP2-silenced plants is very similar to the phenotype of SA-insensitive SAR-defective npr1/nim1/sai1 Arabidopsis mutants (31-34). NPR1 is an important signal transducer that functions downstream of SA in the defense signaling pathway. This protein contains ankyrin repeats and shares limited homology with the IκBα subclass of transcription factors/inhibitors in animals, which regulate immune and inflammatory responses (35, 36). Recent studies have revealed that NPR1 is maintained in the cytoplasm as an oligomer formed through intermolecular disulfide bonds (37). Treatment with SA (or its analog 2,6-dichloro isonicotinic acid) or infection with pathogens alters the cellular reduction potential, thereby promoting monomerization of NPR1; these monomers then are translocated to the nucleus, a prerequisite for PR-1 gene activation (37, 38). Although these findings provide one mechanism of action for SA, an additional mechanism(s) also must exist to account for the poorer induction of PR-1 expression and disease resistance in transgenic npr1-1 mutant Arabidopsis that constitutively accumulate monomeric, nuclear-localized NPR1 than in 2,6-dichloro isonicotinic acid-treated WT plants (37). Furthermore, NPR1 was recently shown to regulate SA-mediated suppression of jasmonic acid signaling via a mechanism that does not require nuclear localization (39). Future analyses with an Arabidopsis knock-out mutant(s) lacking the SABP2 ortholog(s) are needed to elucidate the respective contributions and locations of NPR1 and SABP2 in the SA signaling pathway(s). Nonetheless, the similarities between SABP2-silenced and npr1/nim1/sai1 plants strongly argue that SABP2 is an important component of this pathway that functions at a point downstream of SA.

If SABP2 has a direct role in SA signaling, the question arises why its orthologs were not identified by genetic screens for Arabidopsis mutants displaying enhanced disease susceptibility (7, 11, 12). A likely explanation is that Arabidopsis contains an 18-member gene family whose encoded proteins are 46-71% similar to SABP2. Thus, if some of these proteins are functionally redundant, mutation of a single family member would be unlikely to produce a detectable phenotype. Supporting this possibility, 10 of the Arabidopsis SABP2-like (SABP2L) genes contain the lipase signature sequence and several display specific SA-binding activity (data not shown).

Possible Role(s) for SABP2 During Defense Signaling. The discovery that SABP2 displays SA-stimulated lipase activity and SABP2 is required for local and systemic resistance suggests SABP2's lipase is required to signal resistance. One possible mechanism for resistance-specific SABP2 activation is by means of direct stimulation of its lipase activity by SA. This might be mediated by SA-facilitated displacement of the lid, a surface loop found on many lipases and other α/β fold hydrolases that covers the active site and regulates substrate selection and binding (29). SABP2 activity also may be increased by enhanced gene expression, because SABP2 transcript levels increased in TMV-infected tobacco plants (Fig. 4A).

The mechanism through which SABP2's lipase activity transduces the defense signal is not known. However, there is growing evidence that lipids play an important role in signaling disease resistance. The EDS1 and PAD4 proteins of Arabidopsis, which are putative lipases, are required to transduce the resistance signal after pathogen recognition by a specific class of resistance (R) genes. Although these proteins share little homology with SABP2, all three contain the catalytic triad and the lipase signature sequence (40, 41). Additionally, the ssi2 mutation in Arabidopsis, which impairs fatty acid (FA) desaturase activity and thereby alters cellular FA content, confers constitutive activation of several SA-associated defense responses and suppression of certain jasmonic acid-dependent defenses (42, 43). More recently, a defect in a putative apoplastic lipid transfer protein caused by the dir1-1 mutation was shown to impair systemic, but not local, resistance in pathogen-infected Arabidopsis (44). DIR1 therefore appears to play a role in generating or translocating the SAR signal that moves from inoculated leaves to other parts of the plant. Given that both dir1-1 mutant and SABP2-silenced plants are defective in developing SAR, it is tempting to speculate that SABP2's SA-stimulated lipase activity generates a SAR-inducing lipid (or lipid derivative) that is translocated by the DIR1-encoded lipid transfer protein to the uninoculated parts of the plant.

Because some SABP2L proteins do not bind SA (data not shown), certain family members might bind other ligands, such as stress-associated hormones like jasmonic acid or abscisic acid. Indeed, these proteins may comprise a family of receptors that, on binding their cognate ligand, exhibits enhanced hydrolase (e.g., lipase/esterase) activity. Different members, or sets of members, would likely display distinct substrate specificities, thereby ensuring that the proper response is signaled. Alternatively, sequence similarity between SABP2 and other known proteins, including several plant hydroxynitrile lyases and lecithin (phosphatidylcholine) cholesterol acyl transferase (45) from animals, raises the possibility that some SABP2/SABP2L family members have other enzymatic activities.

In summary, our results suggest that SABP2 is a resistance signaling receptor for SA. The steps activated downstream of this SA effector protein are not yet known. However, the ability of SA to regulate SABP2's lipase activity suggests a mechanism through which lipids/fatty acids are linked to the SA-dependent defense signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

We thank George M. Carman and Sreenivas Avula for helping in the initial lipase assay, Peter M. Waterhouse (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Canberra, Australia) for providing pHANNIBAL and pART27 plasmids, Jihad Attieh for early efforts to purify SABP2, and D'Maris Dempsey for assistance in preparation of the manuscript. This work was partially supported by National Science Foundation Grants IBN-0110272/0241531 and MCB-0110404 and the Triad Foundation through a “Plants and Human Health Grant” to the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research.

Abbreviations: SA, salicylic acid; PR, pathogenesis-related; rSABP2, recombinant SABP2; SABP2L, SABP2-like; SAR, systemic acquired resistance; TMV, tobacco mosaic virus; AP, Amersham Pharmacia.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database [accession nos. AY485932 (SABP2); AAO22676 (A. thaliana), CAA11219 (M. esculenta), P52704 (H. brasiliensis), and Q43360 (O. sativa, Pir7b)].

References

- 1.Dangl, J. L. & Jones, J. D. G. (2001) Nature 411, 826-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt, B. F., III, Hubert, D. A. & Dangl, J. L. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15, 20-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohn, J., Sessa, G. & Martin, G. B. (2001) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 13, 55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flor, H. (1971) Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275-296. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keen, N. T. (1990) Annu. Rev. Genet. 24, 447-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond-Kosack, K. E. & Jones, J. D. G. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 1773-1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dempsey, D., Shah, J. & Klessig, D. F. (1999) Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 18, 547-575. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamb, C. & Dixon, R. A. (1997) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 48, 251-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittler, R., Shulaev, V., Seskar, M. & Lam, E. (1996) Plant Cell 8, 1991-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong, X. (2001) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 309-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glazebrook, J. (2001) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel, B. N. & Brooks, D. M. (2002) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 325-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Camp, W., Van Montagu, M. & Inzé, D. (1998) Trends Plant Sci. 3, 330-334. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draper, J. (1997) Trends Plant Sci. 2, 162-165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirasu, K., Nakajima, H., Rajasekhar, V. K., Dixon, R. A. & Lamb, C. (1997) Plant Cell 9, 261-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devadas, S. K., Enyedi, A. & Raina, R. (2002) Plant J. 30, 467-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, Z., Ricigliano, J. W. & Klessig, D. F. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9533-9537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, Z., Silva, H. & Klessig, D. F. (1993) Science 262, 1883-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durner, J. & Klessig, D. F. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11312-11316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slaymaker, D. H., Navarre, D. A. Clark, D., del Pozo, O., Martin, G. B. & Klessig, D. F. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11640-11645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du, H. & Klessig, D. F. (1997) Plant Physiol. 113, 1319-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo, A., Salih, G. & Klessig, D. F. (2000) Plant J. 21, 409-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, J., Koga, Y., Nakano, H. & Yamane, T. (2002) Protein Eng. 15, 147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith, N. A., Singh, S. P., Wang, M. B., Stoutjesdijk, P. A., Green, A. G. & Waterhouse, P. M. (2000) Nature 407, 319-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah, J. & Klessig, D. F. (1996) Plant J. 10, 1089-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar, D., Verma, H. N., Tuteja, N. & Tewari, K. K. (1997) Plant Mol. Biol. 33, 745-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang, X., Xie, M., Kim, Y. J., Zhou, J., Klessig, D. F. & Martin, G. B. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 15-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wesley, S. V., Helliwell, C. A., Smith, N. A., Wang, M. B., Rouse, D. T., Liu, Q., Gooding, P. S., Singh, S. P., Abbott, D., Stoutjesdijk, P. A., et al. (2001) Plant J. 27, 581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nardini, M. & Dijkstra, B. W. (1999) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9, 732-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaffney, T., Friedrich, L., Vernooij, B., Negrotto, D., Nye, G., Uknes, S., Ward, E., Kessmann, H. & Ryals, J. (1993) Science 261, 754-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao, H., Bowling, S. A., Gordon, A. S. & Dong, X. (1994) Plant Cell 6, 1583-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaney, T. P., Friedrich, L. & Ryals, J. A. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2, 6602-6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glazebrook, J., Rogers, E. E. & Ausubel, F. M. (1996) Genetics 143, 973-982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah, J., Tsui, F. & Klessig, D. F. (1997) Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10, 69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao, H., Glazebrook, J., Clark, J. D., Volko, S. & Dong, X. (1997) Cell 88, 57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryals, J., Weymann, K., Lawton, K., Friedrich, L., Ellis, D., Steiner, H.-Y., Johnson, J., Delaney, T. P., Jesse, T., Vos, P. & Uknes, S. (1997) Plant Cell 9, 425-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mou, Z., Fan, W. & Dong, X. (2003) Cell 113, 935-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinkema, M., Fan, W. & Dong, X. (2000) Plant Cell 12, 2339-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spoel, S. H., Koornneef, A., Claessens, S. M. C., Korzelius, J. P., Van Pelt, J. A., Mueller, M. J., Buchala, A. J., Métraux, J.-P., Brown, R., Kazan, K., et al. (2003) Plant Cell 15, 760-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falk, A., Feys, B. J., Frost, L. N., Jones, J. D., Daniels, M. J. & Parker J. E. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3292-3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jirage, D., Tootle, T. L., Reuber, T. L., Frost, L. N., Feys, B. J., Parker, J. E., Ausubel, F. M. & Glazebrook, J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 13583-13588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kachroo, P., Shanklin, J., Shah, J., Whittle, E. J. & Klessig, D. F. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9448-9453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shah, J., Kachroo, P., Nandi, A. & Klessig, D. F. (2001) Plant J. 25, 563-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maldonado, A. M., Doerner, P., Dixon, R. A., Lamb, C. J. & Cameron, R. K. (2002) Nature 419, 399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonas, A. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1529, 245-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]