Abstract

This study investigates the role of two processes, cue enhancement (learning to attend to acoustic cues which characterize a speech contrast for native listeners) and cue inhibition (learning to ignore cues that do not), in the acquisition of the American English tense and lax ([i] vs.[I]) vowels by native Spanish listeners. This contrast is acoustically distinguished by both vowel spectrum and duration. However, while native English listeners rely primarily on spectrum, inexperienced Spanish listeners tend to rely exclusively on duration. Twenty-nine native Spanish listeners, initially reliant on vowel duration, received either enhancement training, inhibition training, or training with a natural cue distribution. Results demonstrated that reliance on spectrum properties increased over baseline for all three groups. However, inhibitory training was more effective relative to enhancement training and both inhibitory and enhancement training were more effective relative to natural distribution training in decreasing listeners’ attention to duration. These results suggest that phonetic learning may involve two distinct cognitive processes, cue enhancement and cue inhibition, that function to shift selective attention between separable acoustic dimensions. Moreover, cue-specific training (whether enhancing or inhibitory) appears to be more effective for the acquisition of second language speech contrasts.

Keywords: Phonetic learning, non-native speech perception, English, Spanish, vowels

1.0 Introduction

The process of phonetic learning in both first and second language acquisition may be understood through the operation of mechanisms of selective attention (Francis, Kaganovich & Driscoll-Huber, 2008; Francis & Nusbaum, 2002; Kuhl & Iverson, 1995; Iverson & Kuhl, 1995; Jusczuk, 1994; Pisoni, Lively, & Logan, 1994) formalized in terms of a class of models that may be called attention-to-dimension models (Francis & Nusbaum, 2002; Goldstone, 1994; 1998; Nosofsky, 1986). These models represent perceptual space in terms of a multidimensional structure where each dimension corresponds to a feature along which categorization is made. Perceptual similarity is treated in terms of distance along a particular dimension: Tokens that are perceived to be similar appear close together while tokens that are perceived as different are farther apart from each other.

Two mechanism of selective attention are able to change or “warp” the structure of this space. Enhancement of attention to a particular dimension (or sections of a dimension) results in “stretching” or increase of the perceptual distance between tokens, reflecting increasing differentiability of the tokens in a process of acquired distinctiveness. In contrast, inhibition or withdrawal of attention “shrinks” unimportant dimensions (or sections of dimensions) resulting in decreased perceptual distance between tokens and poorer differentiation in a process of acquired similarity (Gibson, 1969; Liberman, 1957; Goldstone, 1994; Francis, et al. 2008; Francis & Nusbaum, 2002).

The transition in infants’ perception from general auditory processing schemes to a more language specific mode of perception (Aslin, Pisoni, Hennessy & Perey, 1981; Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992; Werker, Guilbert, Humphrey, & Tees, 1981; Werker & Tees, 1984) may be understood in terms of allocating more attention to those cues which are relevant for distinguishing native language speech contrasts and withdrawing attention from those that are not (Jusczyk, 1990; Jusczyk, 1994). Research on infant-directed speech provides support for this view. For example, mothers produce vowels with exaggerated formant frequencies in order to enhance infants’ attention to specific vowel contrasts in their native language (Burnham, Kitamura, & Vollmer-Conner, 2002; Kuhl et al., 1997; Liu, Kuhl, & Tsao, 2003). Simultaneously, the lack of exposure to those acoustic cues that are not phonetically distinctive in the native language (e.g. vowel duration) results in inhibition of attention and a loss of sensitivity towards them (Iverson et al., 2003; Kuhl et al., 2008; Nenonen, Shestakova, Huotilainen, & Naatanen, 2003; Werker et al., 2007).

Because of such experience-induced changes in the distribution of attention, the auditory space of adult listeners is restructured or “warped” with respect to that of infants and adult speakers of other languages (Best, 1995; Iverson & Kuhl, 1995; Kuhl & Iverson, 1995; Pisoni et al., 1994) leading to significant difficulties in distinguishing second language (L2) phonetic contrasts that are not employed in their native language. For example, previous research demonstrated that Japanese listeners paid attention primarily to the frequencies of the second (F2) formant that allowed them to distinguish three /r/, /l/ and /w/ categories on a synthesized English /r/ and /l/ continuum (Yamada & Tohkura, 1992). Iverson et al., (2003) found that Japanese listeners ignored the variability along the third formant (F3) that is employed as a primary cue for the differentiation of /r/-/l/ contrast by native English listeners. That is, although Japanese listeners were sensitive to, and could detect, within-category differences along the F3 dimension, their attention was directed to the F2 frequency with the result that they used this dimension for categorization instead of F3, interfering with their ability to recognize these non-native speech sounds in an English-like manner (Iverson et al., 2003). Consequently, in order to achieve English-like perception of this contrast, many researchers have argued that native Japanese listeners have to learn to redirect (enhance) their attention to the under-attended F3 formant frequencies (Bradlow, Pisoni, Akahane-Yamada, & Tohkura, 1997; Bradlow, Akahane- Yamada, Pisoni, & Tohkura 1999; Iverson, Hazan, & Bannister, 2005; McCandliss, Fiez, Protopapas, Conway, & McClelland, 2002). In this sense, the enhancement of attention towards acoustic cues that are relevant in a second language (but not in the native language) could parallel the operation of the mechanism of enhancement of attention involved in first language acquisition (Pisoni et al., 1994).

Similarly, adult non-native listeners have to actively overcome interference from too much attention directed towards specific acoustic cues that are detrimental in the target language. For example, the successful acquisition of the American English /r/ and /l/ categories by native Japanese listeners might involve not only enhancement of attention towards the under-attended F3 formant frequencies, but also a simultaneous inhibition of attention towards the frequencies of the second (F2) formant, which is not employed by native American listeners for this contrast (Iverson et al., 2005).

Most current research, with the exception of two recent studies (Goudbeek, Cutler, & Smith, 2008; Iverson et al., 2005: see below), has focused primarily on enhancement without considering the possibility of the simultaneous operation of inhibitory processes in the acquisition of non-native sounds (Jamieson & Morosan, 1986, 1989; McCandliss, et al., 2002; Pruitt, Jenkins, & Strange, 2006). With this in mind, the present study was designed to investigate the operation of mechanisms of both enhancement and inhibition by comparing the outcomes of three short-term laboratory training techniques. The aim of this training was to increase native Spanish listeners’ attention to spectral properties as compared to duration, cues that can both be used for the categorization of American English tense and lax vowel contrast (e.g. [i] as in sheep and [I] as in ship) but that have different importance for native English listeners.

In English tense and lax vowels can be distinguished primarily along two acoustic dimensions: Spectrum (vowel quality, related mainly to the first three formant frequencies) and duration (vowel length). Tense vowels are longer than lax vowels and are more peripheral in the acoustic vowel space (have lower F1 and higher F2 and F3 values) relative to lax vowels (Hillenbrand, Getty, Clark, & Wheeler, 1995; Ladefoged & Maddieson, 1996). Native English speakers have been shown to rely predominantly on spectral properties when identifying these vowels, with vowel duration playing only a secondary role (Hillenbrand, Clark, & Houde, 2000).

However, numerous studies have demonstrated that inexperienced Spanish listeners tend to rely predominantely on vowel duration for the identification of English tense and lax vowels (Bohn, 1995; Escudero & Boersma, 2004; Escudero, 2006; Kondaurova & Francis, 2008). These findings are accounted for by several hypotheses. Bohn (1995) proposed that because native Spanish listeners are not exposed to an English-like tense and lax contrast, they become linguistically “desensitized” to its spectral differences and, instead, employ vowel duration due to its greater psychoacoustic salience in comparison to spectral properties. In contrast, Escudero and Boersma (2004) suggested that the primary reliance of native Spanish listeners on vowel duration can be accounted by the application of an L1 acquisition mechanism that detects the statistical distribution of duration in English productions. They argue that, as native Spanish listeners do not have duration-based categories in their native language, categorization along the duration dimension is not impeded by their native phonological system, whereas categorization according to spectral properties is. Finally, Morrison (2008, 2009) hypothesized, based on of the observation that native Spanish listeners’ responses show a positively correlated use of duration and a negatively correlated use of spectral properties (a so-called reversal response) that there is an earlier stage of perception even than the duration-based stage proposed by Escudero and colleagues. This is described as a multidimensional-category-goodness-difference stage in which vowels that are perceived as good matches for Spanish /i/ (those with shorter duration, lower F1 and higher F2) are labeled as English [I] vowels. Vowels that are perceived as poor matches (those with either longer duration, or higher F1 and lower F2, or both) are labeled as English /i/. Thus, since only duration cues are positively correlated with English speakers’ productions, native Spanish listeners use them for learning this contrast.

In general, as previous studies suggest (Bohn, 1995; Escudero & Boersma, 2004; Escudero, 2006; Kondaurova & Francis, 2008; Morrison, 2008; 2009) the acquisition of English tense and lax vowel contrast would appear to be difficult for native Spanish listeners, and therefore could provide an ideal context for evaluating consequences of several training methods that are intended to induce a shift of attention between acoustic cues.

In the present study, two auditory training methods, adaptive training (Jamieson & Morosan, 1986, 1989; Iverson, et al., 2005; McCandliss et al., 2002) for cue enhancement, and high variability along the irrelevant dimension (Goudbeek, et al., 2008; Holt & Lotto, 2006; Iverson, et al., 2003) for cue inhibition, were employed in order to restructure listeners’ perceptual space. A third group of Spanish listeners was also trained with a native English-like distribution in which spectrum and duration cues covaried in a condition simulating exposure to a more natural type of cue distribution.

Enhancement of listeners’ attention to a category-relevant dimension was targeted with adaptive training (Terrace, 1963; Jamieson & Morosan, 1986, 1989; Iverson et al., 2005). In this method, training starts with clearly distinguishable stimuli with values exaggerated in comparison to normal acoustic differences. Gradually, the perceptual difference between the stimuli is reduced so that the task to identify a specific contrast is never too difficult and there are few errors but perceptual acuity gradually improves over the course of training. Perceptual fading has been employed successfully for remediating language-processing deficits in children with specific language impairment (Merzenich, Jenkins, Johnson, Schreinder, Miller, & Tallal, 1996; Tallal, et al., 1996) and in second-language acquisition studies (Jamieson & Morosan, 1986, 1989; Iverson, et al., 2005; McCandliss, et al., 2002; Pruitt, et al., 2006).

However, second language acquisition studies using adaptive training method have thus far examined only a limited number of contrasts, such as the perception of the English fricatives /θ/ as in thin and / ð / as in the by native French listeners (Jamieson and Morosan, 1986, 1989), the identification of American English /r/ vs. /l/ by native Japanese listeners (Iverson, et al., 2005; McCandliss, et al., 2002) and the perception of the Hindi dental vs. retroflex place contrast by native English and Japanese listeners (Pruitt, et al., 2006). The present study extends the application of this method to the perceptual learning of English vowels, a contrast that has not been trained before using these techniques.

Inhibitory training introduces irrelevant variability along the initially more-attended dimension, encouraging listeners to ignore it in categorization (Francis, Baldwin, & Nusbaum, 2000; Holt & Lotto, 2006; Melara, Marks, & Potts, 1993). Only two studies thus far have used inhibitory methods to train perception of non-native speech sounds. Iverson et al., (2005) investigated the acquisition of the English /r/-/l/ contrast by native Japanese listeners and Goudbeek, et al. (2008) examined the acquisition of Dutch high front rounded/unrounded vowels by Spanish and American English listeners. Although both studies found this method generally effective, a number of questions still remain. For example, although Iverson et al., (2005)compared inhibition training to adaptive and high variability phonetic training, no clear differences were found between these techniques, perhaps because of the large number of secondary acoustic cues that were involved in the study. Similarly, although participants in the study by Goudbeek et al., (2008) gave less weight on the posttest to the dimension they were trained to inhibit, some of them already did not employ this dimension on the pretest. Therefore, the present study is designed to extend the application of this training technique to another vowel contrast and under conditions that provide stricter control over both available secondary cues and participants’ pretest performance.

Finally, a third method of training is used here to provide listeners with examples clustered around prototypical values (Pisoni, Aslin, Perey, & Hennesy, 1982; Wade, Jongman, & Sereno, 2007) for both duration and spectrum cues. This method was designed to be comparable to the High Variability Phonetic Training technique (HVPT) (Bradlow et al., 1997; 1999; Lively, Logan, & Pisoni, 1993; Logan, Lively, & Pisoni, 1991) but with some limitations. The present study did not introduce the variability due to different talkers or different phonetic environments as the true HVPT does, because the goal of this research was to identify consequences of two distinct processes, enhancement and inhibition of attention. The true HPVT, however, combines the two, as the exposure to stimuli produced by different talkers in different environment both enhances attention to relevant dimensions and inhibits it to irrelevant ones (Logan et al., 1991), making it difficult to identify the operation of one in isolation from the other.

In order to better evaluate changes in the structure of perceptual space of Spanish listeners as a result of training, the transfer of training to a new phonetic context and to naturally produced words was also to be assessed. Successful transfer of training suggests that participants have learnt some characteristics of a contrast which they can generalize to new stimuli or tasks, meaning that robust learning has occurred (Logan & Pruitt, 1995).

It is predicted, based on previous studies, that all training methods employed in the current study should redirect Spanish listeners’ attention away from duration and towards spectral properties although there could be differences in specific details of what dimensions are affected, and how. For example, enhancement training of spectral properties should increase attention of native Spanish listeners towards this cue (Jamieson & Morosan, 1986, 1989; Iverson, et al., 2005; McCandliss, et al., 2002), but it is not clear to what extent this would simultaneously affect the withdrawal of attention from duration. In contrast, in inhibitory training where spectral properties are the only available dimension for categorization, attention towards duration should be decreased to some degree, although it is not clear whether it can be eliminated entirely (Francis, et al., 2000; Goudbeek, et al., 2008; Iverson et al., 2005). Finally, training with prototypical exemplars may increase attention to spectrum if this method is sufficiently similar to high variability training (Bradlow et al., 1997; 1999; Lively et al., 1993; Logan et al., 1991). However, there are no clear predictions from previous literature about what might happen with duration using this training technique. If short-term laboratory training is successful, it could result in robust learning as seen from the generalization to a new phonetic context (Francis, et al., 2000 McCandliss, et al., 2002; McClausky, Pisoni, & Carrell, 1983; Pruitt, et al., 2006) and possibly to naturally produced words (Jamieson and Morosan, 1986), although what training method will be most effective as seen from generalization remains to be determined.

2.0 Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were native speakers of American English (6 women, 4 men) and Spanish (25 women, 36 men) as determined by a language background questionnaire prior to testing. The American English participants were undergraduate and graduate students at Purdue University, mean age 23.1 years, who grew up in the Midwest United States with some exposure to other languages. Spanish participants were undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and/or instructors at Purdue University from 13 Latin American countries and Spain, with the majority from Mexico, Colombia, Spain and Chile. Out of 61 Spanish speakers who participated in initial prescreening, 29 participants (12 women and 17 men, mean age 27.4 years) were chosen for further training based on their prescreening results. They were randomly assigned to three groups (Inhibition N = 9, Adaptive N = 10 and Natural Correlation N = 10). Average demographic and language background data on all Spanish participants are presented in Table 1 (Appendix A) and separate data on each Spanish training group are presented in Table 2 (Appendix B). All participants reported no history of speech or hearing disability and passed a standard hearing test using an M 120 Beltone Audiometer (pure tone audiometry, binaural, at octave intensities from 500 Hz to 8 kHz at 20 dB of hearing level). All participants were paid for their participation in the experiment under a protocol approved by the Committee for Human Research Subjects at Purdue University.

2.2 Stimuli

2.2.1. Synthetic Stimuli

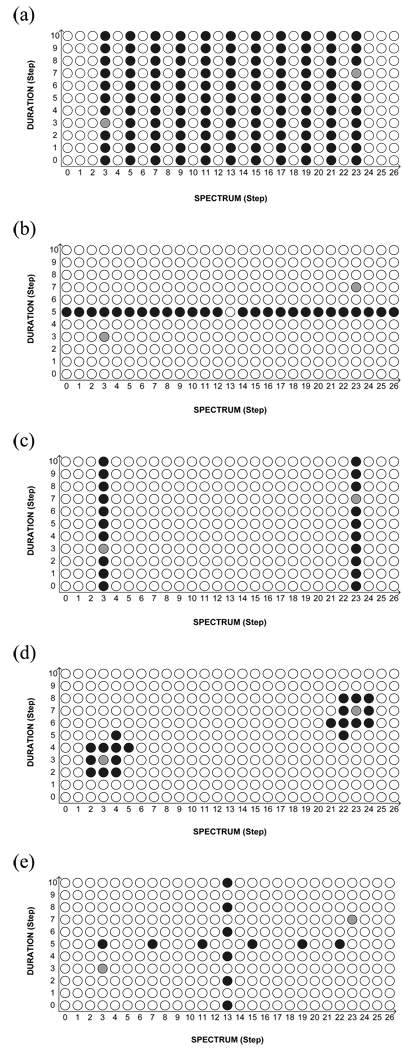

A set of 297 sheep-ship and beat-bit tokens was created out of which several subsets were extracted for subsequent tasks as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Identification task: 121 tokens (black and grey circles). Spectrum steps (spectral properties of the vowel, F1–F4, Hz) range from sheep/beat (Step 0) to ship/bit (Step 26). Duration steps (vowel duration) range from 198.5 ms (Step 0) to 71 ms (Step 10) for sheep-ship continua and from 225 ms (Step 0) to 97.5 ms (Step 10) for beat-bit continua. The two grey colored circles (Spectrum Step 3 and Duration Step 3; Spectrum Step 23 and Duration Step 7) are stimuli with natural spectral and duration values.

(b) Adaptive Training: 26 tokens (black circles). Duration Step 5 (vowel duration) is 134.5 ms. The two grey colored circles are stimuli with natural spectral and duration values and are given for reference but were not used for training in this set.

(c) Inhibition Training: 22 tokens (black circles and two grey circles). Spectrum steps (spectral properties of the vowel, F1–F4, Hz) have natural sheep (Step 3) and ship (Step 23) values. The two grey colored circles are stimuli with natural spectral and duration values.

(d) Natural Correlation Training: 22 tokens (black circles and two grey circles). The two grey colored circles are stimuli with natural spectral and duration values.

(e) Discrimination task: 12 tokens (black circles). The two grey colored circles are stimuli with natural spectral and duration values and are given for reference but were not used for training in this set

All tokens consisted of a synthetic vowel ranging from [i] to [I] that was inserted between a naturally produced [∫] and [p] (sheep-ship set) or [b] and [t] (beat-bit set). The 297 original stimuli were created according to the following procedure: A 34-year-old male native speaker of a Midwestern dialect of American English produced several examples of the words sheep and beat in isolation. All tokens were recorded in a double-walled sound booth (IAC Inc.) in the hearing clinic at Purdue university using a Marantz digital audio recorder (PMD 660) and a hypercardioid microphone (Audio-Technica D1000HE) positioned on a boom approximately 20 cm in front and 45° to the right of the talker's lips. Recordings were made at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz with 16-bit quantization rate (QR), and were subsequently peak-amplitude normalized to the maximum QR using the Praat 4.1.21 program running on a Dell Optiplex/Windows XP computer with a Sound Blaster Live! sound card.

From the recorded set one token of sheep and beat were selected using the criterion that there be no abrupt changes in formant movement throughout the periodic portion of the signal, no abrupt changes in fundamental frequency, no clicks and minimal extraneous noise (to facilitate resynthesis) throughout the recording. In addition, the final consonant closure in both sheep and beat tokens should be fully released.

Initial and final consonants from one sheep and one beat token were manually extracted. In the sheep token, the [ ∫ ] was defined as starting at the beginning of frication noise and ending at the end of the frication noise before the start of the vowel periodic portion. The start of the periodicity was defined as a point at the first zero crossing where the first period of the waveform began. The duration of the [ ∫ ] was 216 ms. Then the [p] consonant was extracted starting from the beginning of the salient gap to the end of the release of the closure. The beginning of the silient gap was defined as a point at the last zero crossing of the last period of the vowel waveform. The release of the closure was defined as a sharp spike of noise visible in the wide-band spectrogram. The duration of the [p] was 125 ms. In the beat token, the [b] was extracted from the beginning of closure to the end of the [b] burst and the [t] was extracted starting from the beginning of the silent gap to the end of the release of closure. The duration of the [b] was 13 ms and the duration of the [t] was 215 ms.

Then, for the following resynthesis, a periodic portion of the vowel waveform was manually extracted from the beat token starting from the end of the [b] burst to the last zero crossing of the vowel waveform before the silent gap. The vowel in this token was chosen as it was used successfully for resynthesis in a previous study (Kondaurova & Francis, 2008).Vowel duration, intensity and the first four formants (F1, F2, F3 and F4) were measured using the standard LPC analysis settings implemented in Praat 4.1.21. The vowel duration was 171 ms, the first formant was 254 Hz, the second formant was 2076 Hz, the third formant was 2962 Hz and the forth formant was 3478 Hz. The average intensity was 76 dB.

Manipulation of Source

As a tense vowel source is different from a lax vowel source, the aim of the manipulation was to create the same source so that when filtered, it would not affect the perception of a vowel as tense or lax. A resynthesized source was created using Praat 4.2.21 with the following procedure. First, an artificial intensity tier (contour) was created with the following parameters: the duration of the contour was 171 ms, with the intensity increasing to 30 dB from 0 to 30 ms, rising to 70 dB from 30 to 161 ms, and then falling back to 30 dB from 161 to 171 ms. The aim of creating an artificial intensity contour was to make intensity equal in all vowels along the sheep-ship and beat-bit continua and to avoid audible clicks at the beginning and end of the vowel when its filter characteristics were resynthesized. After creating the intensity contour, a source was extracted from the naturally produced vowel in the beat token. Using the extracted source, a pitch tier was created and turned into a new glottal source signal. After this procedure the newly created glottal source signal was multiplied by the artificial intensity tier (contour) in order to create a new artificial source with neutral properties.

Manipulation of Filter

The artificial filter was created using Praat 4.2.21. The frequency and bandwidth values for the initial ([i]) endpoint were specified as following: F1: 300 Hz, F2: 2410 Hz, F3: 3087 Hz, F4: 3657 Hz and F5: 4500 Hz, with bandwidths of 50, 100, 100, 50 and 50 Hz, respectively. These values were chosen by trial and error so that, after all steps of resynthesis were complete, the vowel formant values were measured to be close to those reported by Hillenbrand et al., (1995). The newly created artificial source was filtered through the new filter to create a synthetic vowel. Then the vowel was peak-amplitude normalized.

Manipulation of Formant Steps

The first four formant center frequencies of the synthetic vowel after resynethesis were extracted using the standard LPC analysis settings implemented in Praat 4.2.21. These values were converted to mel (Taylor, Caley, Black, & King, 1999), and 27 values were calculated for each formant ranging in equal mel steps between the tense and lax values starting from the F1–F4 formant frequencies for tense [i] and ending with those for lax [I] as taken from Table V in Hillenbrand et al. (1995). Each step was approximately one half of one just noticeable difference (JND) for English listeners (Kewley-Port & Watson, 1994), resulting in 10 JNDs between stimuli with formant values for prototypical [i] and [I] (Hillenbrand et al., 1995). Along the spectral continuum, the first three steps (steps 0, 1, 2) and the last three steps (steps 24, 25, 26) had formant values exaggerated beyond the prototypical values reported by Hillenbrand, et al (1995). Step 3 along the spectrum continuum had formant values of a prototypical tense vowel [i], and step 23 had formant values of a prototypical lax vowel (Hillenbrand et al., 1995). Starting with step 0, one version of the syllable (sheep or beat) was resynthesized for each of the 27 formant frequency steps following methods described in the Praat 4.2.21 manual entry for source-filter resynthesis.

Table 5.

Mean values of spectrally-tuned (Beta Spectrum) and duration-tuned (Beta Duration) beta coefficients for native Spanish and English participants

| Beta Spectrum | s.d. | Beta Duration | s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | ||||

| Inhibition | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.15 |

| Adaptive | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| English | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.07 |

| Posttest | ||||

| Inhibition | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Adaptive | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

Manipulation of Duration Steps

From each of the 27 steps along the vowel quality continuum, a continuum ranging in vowel duration was created. For the sheep/ship continuum the duration ranged from 198.5 to 71 ms and for the beat/bit continuum the duration ranged from 225 to 97.5 ms. These endpoints were chosen to allow for 11 duration steps (12.75 ms per step) where steps 0, 1 and 2 and steps 8, 9 and 10 were exaggerated in duration in relation to prototypical tense and lax vowels. Thus, each step equaled half of one JND for native English listeners (Klatt, 1976) resulting in 2 JNDs along the duration continuum between the prototypical stimuli (Hillenbrand et al., 1995).

Generation of Discrimination Task stimuli

For the discrimination set (Figure 1e), the same procedure was carried out creating a set of 297 sheep-ship stimuli as for the identification task, but only 12 of these stimuli were extracted for the task. The formant values (F1, F2, F3 and F4) of the 297 new base stimuli were shifted with respect to the original 297 stimuli described above by 5 Hz along the spectral continuum and their duration was lengthened by 10 ms, ranging from 208.5 to 81 ms, in order to avoid using the same stimuli for discrimination that were employed in the Identification and Training tasks.

2.2.2. Natural Stimuli

For the natural tense/lax words, eight monosyllabic minimal pairs were recorded produced in citation form where each pair consisted of one word with a tense vowel and one word with a lax vowel (Table 3, Appendix C). The words were produced by the same speaker who produced the natural tokens for the generation of the sheep-ship and beat-bit sets. Each pair was recorded three times. Then, one instance of each pair was chosen based on the same criteria as for selecting the initial sheep-ship and beat-bit tokens.

Vowel duration, intensity and the first four formant frequencies (F1, F2, F3 and F4) of each token were measured using the standard LPC analysis settings implemented in Praat 4.1.21. For purposes of measurement, the vowel portion was defined (a) after stops as starting from the end of the burst to the last zero crossing of the vowel waveform before the silent gap; (b) after fricatives and affricates starting from the end of the frication to the last zero crossing of the vowel waveform before the silent gap and (c) in read/rid, from the end of the consonant-vowel formant transitions to the last zero crossing of the vowel waveform before the silent gap.

2.3 Procedure

Control programs for the Identification task (using sheep-ship, beat-bit and natural words stimuli) and for Inhibition, Adaptive and Natural Correlation Training tasks (using sheep-ship stimuli) and for the Discrimination task (using shifted tokens from the sheep-ship set) were generated using E-Prime Version 1.1. All participants were seated in individual cubicles, equipped with a Dell Optiplex/Windows XP computer and a Model RB-620 response pad (Cedrus Corporation). Stimuli were presented via a Soundblaster Live! Soundcard through headphones (Sennheiser, HD 25-1) at a comfortable listening level of 60–65 dBA. Identification and Discrimination tasks were completed on the first and second days (pretest) and again on the seventh day (posttest). Training was carried out on the third to sixth days. Prior to the beginning of the experiment, it was determined that each participant knew all of the words they would be presented with.

In the Identification task, on each trial the listener heard one stimulus (up to 636.5 ms) from the sheep-ship set. The total duration of each stimulus was calculated as a sum of the duration of the initial [ ∫ ] consonant (216 ms), the duration of the periodic (vowel) portion (between 71 and 198.5 ms), and the duration of the [p] consonant (127 ms), plus a 25 ms silence interval before and a 75 ms silence interval after the token. The duration of silence intervals was chosen by trial and error so that the stimulus sounded natural, without an abrupt beginning and/or end. There was also a simultaneous presentation of sheep and ship pictures on the screen. Pictures were chosen instead of written words to avoid a previously noted orthographic effect: Written English “i” that often represents an [I] sound (e.g. in bit) is associated by literate Spanish listeners with the Spanish [i] sound because, in Spanish orthography, “i” represents the sound [i] (Flege et al., 1997; Escudero, & Boersma, 2004).

The pictures remained on the screen until the listener pressed a button on the response pad corresponding to either sheep (left button) or ship (right button) response alternatives1. Then there was a short pause (250 ms) followed by a blink of the screen (250 ms) to indicate the start of a new trial. Each trial was self paced with no limit on time to respond. In total, there were 605 trials, presented in 5 blocks of 121 trials per block (121 different stimuli per block). All trials within a block were presented in random order. Before the experiment began, there was a practice session using the words cat and cut where responses were not recorded. The duration of the Identification task was 30 minutes total.

The structure of the Identification task using the beat-bit and natural words sets was exactly the same as for the sheep-ship set except for the stimulus duration (in both tasks) and the number of trials in the natural words set. The duration of one stimulus for the beat-bit set was up to 485 ms, calculated as the sum of the durations of the initial [b] (13 ms), the duration of the periodic (vowel) portion (97.5 to 225 ms), the duration of the [t] (215 ms), and the duration of two silent intervals, each approximately 16 ms before and after the token. The duration of one stimulus in natural words set was up to 509 ms depending on the length of the recorded words. In the natural words set, in total, there were 400 trials, presented in 5 blocks of 80 trials per block (16 stimuli repeated 5 times each). In both the beat-bit and natural words sets, participants saw written words where beat or a naturally produced word with a tense vowel (e.g. deed) always corresponded with the left button and bit or a naturally produced word with a lax vowel (e.g. did) always corresponded with the right button. The order of the presentation of the stimuli sets in the identification task was fixed. First, participants heard the sheep-ship set, then the beat-bit set and, finally, the natural words set.

Adaptive, Inhibition and Natural Correlation Training had the same structure as the Identification task with a few small differences. In training, there was an upper time limit on responses set at 3000 ms from the start of a stimulus. After a participant responded (or after 3000 ms), feedback appeared informing the participant about her/his performance. The feedback remained on the screen until participants pressed any button on the response pad in order to continue with the experiment. After they pressed a button, they again heard the same stimulus with a simultaneous visual presentation of the correct picture/answer. Then a screen appeared informing participants how many trials they have completed (1100 ms), followed by the presentation of a burst of white noise (1250 ms) to mask echoic memory of the feedback token. After the noise was presented, a new trial started. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible.

In Inhibition and Natural Correlation Training, in each session, there were 330 trials, presented in 3 blocks of 110 trials per block (22 stimuli repeated 5 times each). All trials within a block were presented in random. Each session averaged 30 minutes with 2 hours of training in total.

In the Adaptive Training task, each block consisted of 20 randomly ordered trials each containing one of the two tokens. The first block contained step 3 and step 23 tokens. If the participant was more than 80% correct on that block, the program switched to a block with tokens that were closer to each other along the spectrum dimension (e.g. steps 4 and 22). However, if a participant was less than 80% correct, the program switched to a block containing stimuli that were farther apart (e.g. steps 2 and 24). Finally, if any given block was completed more than two times, the program stopped and was started again manually at steps 3 and 23. This continued until the total running time of each Adaptive Training session was 30 minutes (2 hours total).

In the Discrimination task, where only tokens from the sheep-ship continuum were used, on each trial listeners heard two stimuli, each no longer than 646 ms (with the total duration calculated in the same manner as for the Identification task stimuli, but with the duration of the vowel portion increased by 10 ms) and separated by a short (500 ms) inter-stimulus interval.

The presentation of the first stimulus was accompanied by a simultaneous visual presentation of two words same and different on the computer screen. The words same and different remained on the screen until after participants pressed a button on the response pad corresponding to either same (left button) or different (right button). After a response was made, there was a short pause (250 ms) followed by a blink of the screen (250 ms) to indicate the start of a new trial. Participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible, but each trial was self paced with no limit on time to respond.

In the Discrimination task there were a total of 110 trials, divided between five blocks which had identical structure. In each block, there were six pairs (repeated twice) of same stimuli. Participants also heard five different pairs (presented once in each order, or 10 pairs in total). Consequently, there were twenty two pairs (12 same and 10 different) in each block. All pairs were presented in random order within each block. The average running time was 7 minutes. Before the experiment began, there was a practice session consisting of four trials with naturally recorded tokens of the words cat and cut The structure of the practice session was identical to the actual experiment but responses were not recorded.

3.0 Results

3.1 Prescreening

3.1.1. Assignment to training groups

Identification (ID) functions for the sheep-ship set were calculated for each subject as the proportion of [I] responses to all 11 stimuli sharing a given duration or spectrum value (Bohn, 1995;Escudero & Boersma, 2004; Kondaurova & Francis, 2008). Then, the difference between the low and high ends of the ID functions for each dimension was calculated by subtracting the proportion of [I] responses at the low end (step 3 for spectrum or step 0 for duration) from that at the high (step 23 for spectrum and step 10 for duration). These differences were named “spectrum reliance” and “duration reliance” respectively. Then the ratio of the absolute values of these measures (the “spectrum-to-duration ratio”) was calculated by dividing spectrum reliance by duration reliance. Absolute values were chosen due to the fact that some native Spanish participants demonstrated negative signs for the endpoint difference along either spectrum or duration dimension or both. The negative sign for both spectrum and duration dimensions suggests that they confused the labels referring to tense (sheep) and lax (ship) tokens. This finding agrees with previous observations (Escudero & Boersma; 2004; Flege, 1991; Morrison, 2008), although it is beyond the scope of the present study to analyze which factors underlie such a pattern of responses. However, as the negative sign does not affect the weight given to a specific dimension, absolute values were used for further statistical analysis.

Thirty native Spanish participants were identified as having a spectrum-to-duration ratio less than 1 (indicating that the listener weighted duration greater than spectrum) and 31 as having a ratio greater than 1 (indicating that they weighted spectrum greater than duration). Appendix D presents an analysis of which individual background factors might contribute to the relative weighting of spectral and duration cues by all 61 Spanish listeners who participated in the pretest before the experiment began.

Twenty-four native Spanish participants whose spectrum to duration ratio was less than 1 agreed to continue with the training portion of the experiment. Five additional participants whose ratio was close to 1 (indicating an equal reliance on duration and spectrum) were also invited to participate in order to increase the overall number of trained participants. All twenty-nine participants were randomly assigned to one of three training groups, Inhibition (M ratio = 0.45, SD = 0.53), Adaptive (M ratio = 0.41, SD = 0.49) and Natural Correlation (M ratio = 0.40, SD = 0.42). In contrast, the mean absolute ratio for the American English group was 10.65 (SD = 8.61), suggesting that these listeners relied predominantly on Spectrum.

3.1.2. Individual Background Factors

In order to examine whether participants assigned to the Adaptive, Inhibition and Natural Correlation Training groups (see Table 2, Appendix B) differed in terms of individual background factors that might influence training results, a series of one-way ANOVAs with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive, Natural Correlation) was run separately for each factor.

The results demonstrated a strong significant effect of Age between the three groups, F (2,26) = 4.72, p = 0.017. Post Hoc analysis showed a significant difference, p = 0.016 between Inhibition (M = 29.6 years, SD = 3.3) and Natural Correlation (M = 24.8 years, SD = 4.13) groups. A significant difference was also found in the age at which participants started education in the USA (Start of US education), F (2,26) = 7.155, p = 0.005, with the Inhibition group starting at 26.08 years (SD = 4.65), the Adaptive group at 26.20 years (SD = 2.18) and the Natural Correlation group at 21.12 years (SD = 1.1). Post Hoc analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the Natural Correlation and Adaptive groups, p = 0.008 and between the Natural Correlation and Inhibition groups, p = 0.016. Finally, the self-reported percent of English daily use on a 100% scale (English daily use, %) was different between some groups, F (2,26) = 4.75, p = 0.017. Post Hoc analysis showed that there was a significant difference between the Natural Correlation (M = 63 %, SD= 25.73 %) and the Adaptive group (M = 31 %, SD = 22.21 %) meaning that participants in the Natural Correlation group reported using English more often than participants in the Adaptive Training group. However, the Inhibition group (M = 41%, SD = 22.88%) did not differ significantly from either the Natural Correlation group or the Adaptive Training group.

In general, the comparison of background factors showed that participants in the Natural Correlation group were younger, started their education in the USA at an earlier age and self-reportedly used English to a greater daily extent as compared to Inhibition and/or Adaptive Training groups. Because all of these variables are associated with improved L2 speech learning, the Natural Correlation Training group may have been at advantage in comparison to other two groups with respect to training outcomes.

3.2 Assessment of Training Performance

3.2.1 Training Results

In order to determine whether there was any effect of training (sheep-ship set), the proportion of correct responses and response time to correct responses (Table 4) on each day of training was analyzed. Repeated measures ANOVAs were used, with one within group factor, Day (Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4) for each training group.

Table 4.

Proportion of correct responses and response time to correct responses averaged over each training group

| Proportion of correct responses | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | s.d.a | Day 2 | s.d. | Day 3 | s.d. | Day 4 | s.d. | |

| Inhibition | 0.94 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Adaptive | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.05 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.01 |

| Response time (ms.) to correct responses | ||||||||

| Day 1 | s.d. | Day 2 | s.d. | Day 3 | s.d. | Day 4 | s.d. | |

| Inhibition | 862 | 105 | 772 | 118 | 750 | 117 | 761 | 127 |

| Adaptive | 865 | 171 | 870 | 195 | 846 | 142 | 862 | 139 |

| Natural Correlation | 861 | 99 | 810 | 154 | 819 | 173 | 782 | 115 |

s.d. – standard deviation

For the proportion of correct responses, all groups performed well on Day 1, giving more than 80 % correct responses, and also improved their performance on subsequent days. This improvement was significant for all three groups: Inhibition: F (3, 27) = 5.66, p = 0.004; Natural Correlation: F (3,27) = 4.1, p = 0.015 and Adaptive Training: F (3,27) = 3.24, p = 0.04. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD, all significance levels reported at p <.05 level or better) showed a significant difference between Day 1 and Day 4 for the Inhibition and Adaptive Training group, and between Day 1 and Day 3 for the Natural Correlation group.

For response time to correct responses, there was a significant effect of Day only for the Inhibition group, F (3,27) = 7.31, p = 0.001, not for the Natural Correlation, F (3,27) = 1.55, p = 0.22 or Adaptive groups, F(3,27) = 0.12, p = 0.95. Post Hoc analysis demonstrated a significant difference between Day 1 and Day 2 for the Inhibition group suggesting that the response time decreased only during the first two days probably reaching its critical minimum already on Day 2.

In summary, there was an improvement in performance in all three training groups as assessed by changes in the proportion of correct responses and response time to correct responses. However, while it is possible to explain the increase in the proportion of correct responses in terms of the redistribution of attention for the Inhibition and Adaptive Training groups because their training stimuli were constructed so that improvement could only be achieved by decreasing attention to duration (Inhibition group) or increasing attention to spectrum (Adaptive Training group), it is not possible to conclude from these results alone whether the Natural Correlation group improved due to enhanced attention to spectral or duration dimensions as both could be used for the identification of their stimuli.

The lack of significant decrease in response time in the Adaptive Training group is expected as this training task increased in difficulty with every subsequent successful trial. However, the absence of a decrease in response time in the Natural Correlation group suggests that Natural Correlation training may not have been as successful.

3.2.2 Pre and Posttest Identification Task (sheep-ship continuum)

Analysis

A logistic regression analysis was employed to examine each participant’s response data. Logistic regression analysis is a statistical procedure that has been successfully applied in previous speech perception studies (Goudbeek, et al., 2008; Nearey, 1997). This procedure avoids two problems inherent in previously used end-point difference score quantification (Bohn, 1995; Escudero & Boersma, 2004): A ceiling effect and a susceptibility to noise. It also takes into consideration a non-normal distribution of response data (Morrison, 2005; Morrison & Kondaurova, 2009).

Logistic regression fits a model with bias (intercept) and stimulus-tuned (slope) coefficients, where bias coefficients are employed to calculate boundary locations and the values of the stimulus-tuned coefficients can be used as a measure of the perceptual weight of respective acoustic cues (Nissen, et al., 2005). Thus, when a logistic regression model is fitted to each listener’s proportion of [I] responses, it provides a bias coefficient (α) and spectrally- and duration-tuned coefficients (β spec and β dur), tuned by the duration and spectral properties of the stimuli (x dur and×spec) (see Eq. (1)). The beta-coefficients reflect the perceptual weight assigned to spectral or duration dimensions by each participant: the greater the value of the coefficient, the more weight is given to an acoustic dimension

| (1) |

The deviance statistics G2 was used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of a logistic regression model for each participant’s data in both pretest and posttest. For the explanation of the deviance statistics and its’ application see Morrison (2007) 2.

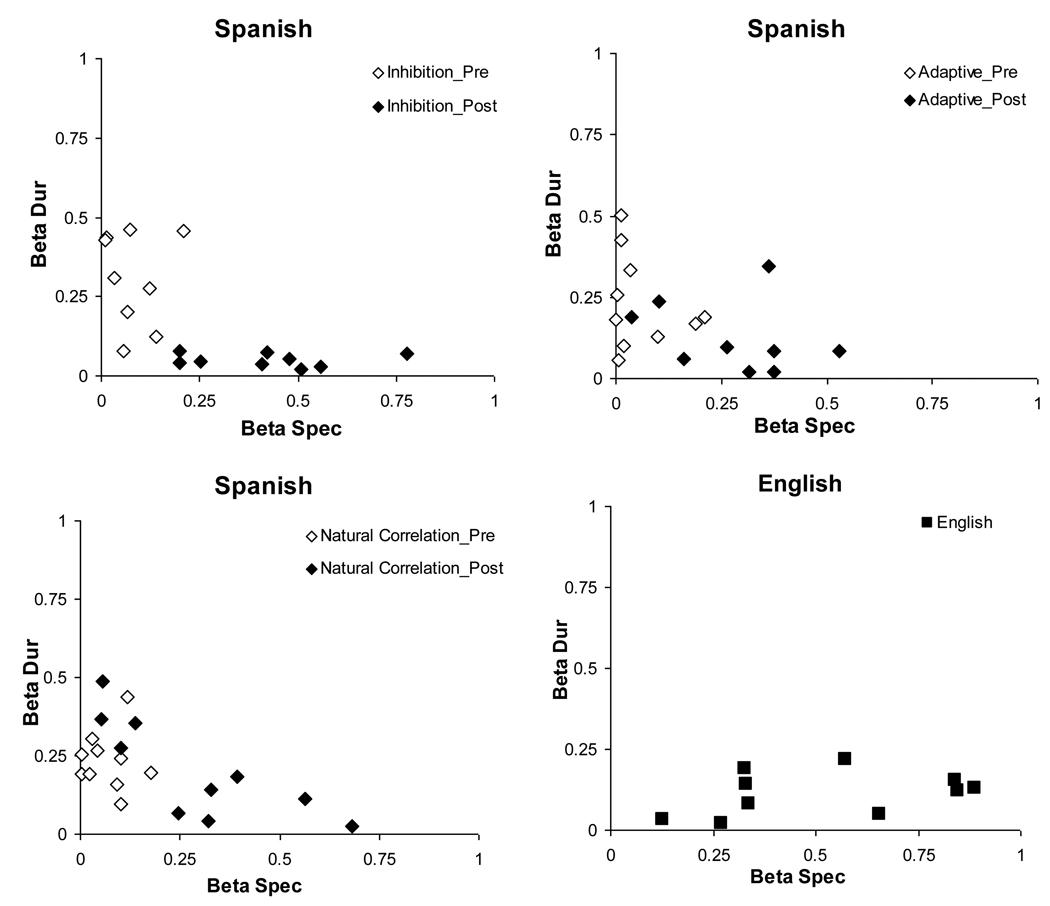

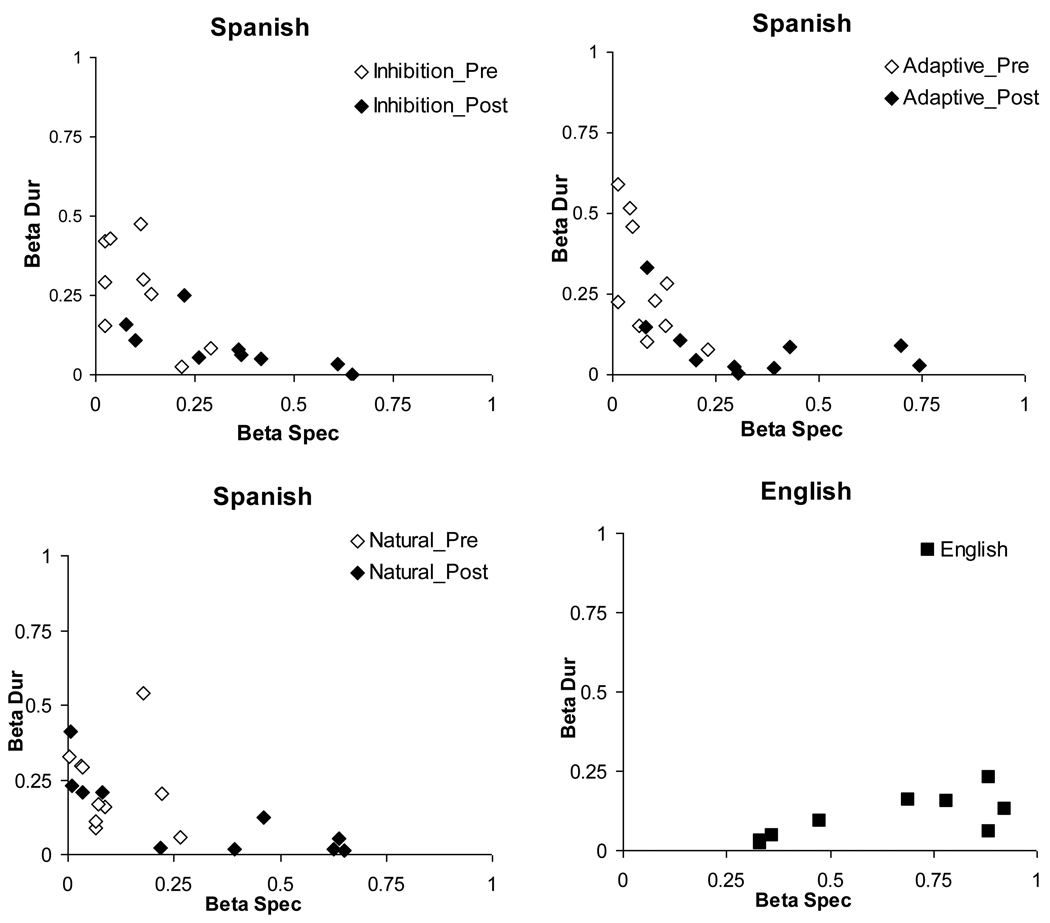

Fig 2 provides a scatterplot of spectrally-tuned (β spec) and duration-tuned (β dur) coefficient values for each native Spanish listener3. English listeners’ results are plotted for reference. Table 5 presents means and standard deviations for each group.

Figure 2.

Native Spanish and English spectrally-tuned (Beta Spec) and duration-tuned (Beta Dur) logistic regression coefficients on the pre- and posttest Identification Task (sheep-ship set).

Results

The first question examined whether training resulted in the change of weighting of spectral and duration dimensions from pretest to posttest in each of the three groups. For each group, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) and one within-group factor Test (Pretest, Posttest) was run on spectrally- and duration-tuned beta coefficients. Along spectrum dimension, results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.63, p = 0.53, a significant effect of Test, F (1, 26) = 45.43, p < 0.001, and no Group×Test interaction, F (2, 26) = 0.73, suggesting an increase in the perceptual weighting of the spectral dimension after training in each group. Along duration dimension, results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.67, p = 0.51, a significant effect of Test, F (1,26) = 20.46, p < 0.001 and a significant Group×Test interaction, F (2, 26) = 4.99, p = 0.01. Planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.05/3 = 0.016 after Bonferroni correction)4 demonstrated a significant difference between pretest and posttest in Inhibition, F (1, 26) = 23.6, p < 0.001 and Adaptive, F (1, 26) = 5.29, p = 0.02, but not in Natural Correlation, F (1, 26) = 0.03, p = 0.58 groups, suggesting that only Inhibition and Adaptive Training methods resulted in a decrease in attention to duration.

The second question investigated which training method was better able to increase attention to spectrum and decrease attention to duration. To answer this question, first, a one-way ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) was run on the difference scores (see Table 6) between spectrum-tuned beta-coefficients at pretest and posttest. Results demonstrated no effect of Group on mean difference scores for spectrum-based beta-coefficients, F (2, 26) = 0.73, p = 0.48, suggesting that all three training methods were similarly effective in increasing attention to spectral properties. Next, a two-tailed t-test with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive) was run on the difference scores between duration-tuned beta-coefficients at pretest and posttest. Difference scores along duration dimension were compared only between the Inhibition and Adaptive Training groups because only these two groups demonstrated significant changes between pretest and posttest in these coefficients.

Table 6.

Mean difference scores of native Spanish participants between spectrally-tuned (Beta Spectrum) and between duration-tuned (Beta Duration) coefficients at pretest and posttest

| Beta Spectrum | s.d. | Beta Duration | s.d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.15 |

| Adaptive | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.22 | 0.21 |

Results demonstrated a significant difference between Inhibition and Adaptive Training difference scores for duration-tuned beta-coefficients, t (17) = 2.1 , p = 0.04 suggesting that Inhibition Training was more effective than Adaptive Training in decreasing attention to the duration dimension.

In summary, the examination of pre- and posttest identification task results demonstrated that all three training methods were successful at inducing listeners to increase the weight given to the spectrum dimension. In this respect, Inhibition Training was also more successful than was Adaptive Training.

Finally, in order to examine whether the perceptual weighting of spectral and duration cues was different between native Spanish and English listeners at pretest and/or posttest, we compared the means of their spectrally-tuned and duration-tuned beta-coefficients using a one-way ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation). At pretest, along the spectral dimension, there was a significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 21.8, p < 0.001 suggesting that mean values of spectrally-tuned coefficients were different between some groups. Planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.05/3 = 0.016 after Bonferroni correction)5 demonstrated a significant difference between English and every training group (Inhibition, F (1,35) = 39.57, p < 0.001; Adaptive Training, F (1, 35) = 45, p < 0.001, Natural Correlation, F (1,35) = 43.86, p < 0.001), suggesting that Spanish listeners relied on spectrum before training to a much lesser extent than did native English listeners. Along the duration dimension, there was also a significant effect of Group, F (3,35) = 4.45, p = 0.008, with planned comparison of means (Bonferroni-corrected α-level = 0.016) showing a significant difference between the English and Inhibition, F (1,35) = 13.06, p < 0.01, between the English and Adaptive Training, F (1,35) = 5.33, p = 0.02 and between the English and Natural Correlation, F (1,35) = 5.23, p = 0.02, groups. These results suggest that, prior to training, all three native Spanish listener groups weighted duration dimension to a greater extent than native English listeners.

At posttest, no effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 1.43, p = 0.24 was found for spectrally-tuned beta coefficients, suggesting that there was no difference in the perceptual weighting of the spectral dimension between any Spanish training group and native English listeners. In contrast, for the duration dimension, there was a significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 3.73, p = 0.01. However, the planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.016) demonstrated no significant difference between the English and any Spanish group. The effect of Group was due to a significant difference between the Inhibition and Natural Correlation groups, p = 0.01 as demonstrated by Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) (α-level = 0.05).6 These results suggest that at posttest native Spanish listeners’ perceptual weighting of both spectral and duration dimensions were found to be not significantly different from native English listeners.

3.2.3 Pre and Posttest Discrimination Task

In order to examine changes in the structure of perceptual space as a result of the redistribution of attention due to three different short-term laboratory training methods, signal detection analysis was used to calculate the sensitivity parameter (d’; Macmillan and Creelman, 2005) between pairs of stimuli distributed along the spectrum and duration dimensions. A difference, whether an increase or decrease, in sensitivity between neighboring pairs of stimuli may indicate the category boundary location (Goldstone, 1996; Liberman, Harris, Hoffman, & Griffith, 1957; Studdert-Kennedy, Liberman, Harris, & Cooper, 1970)

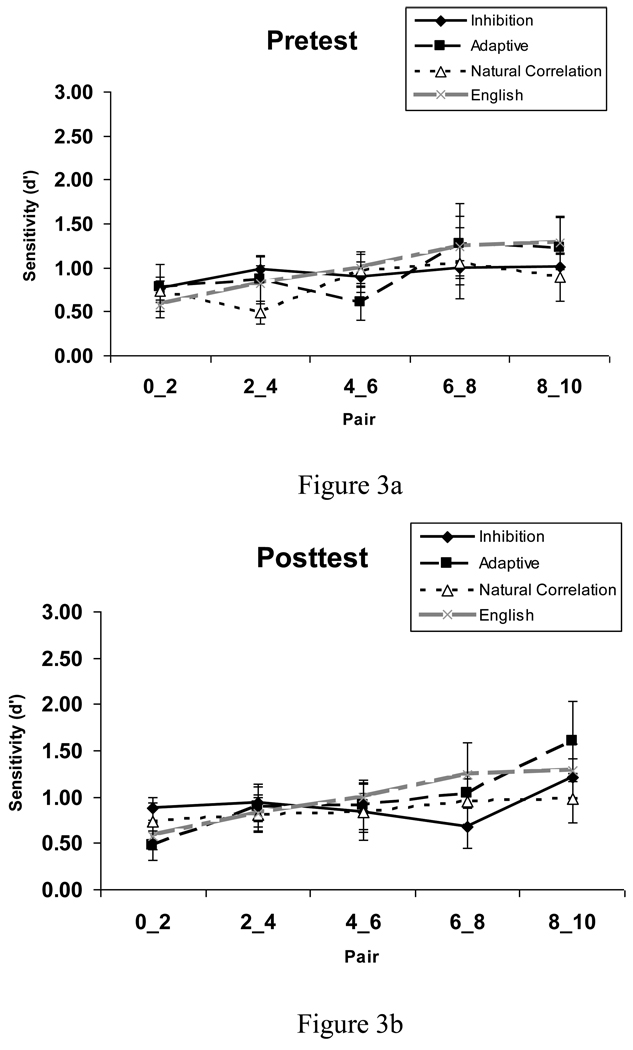

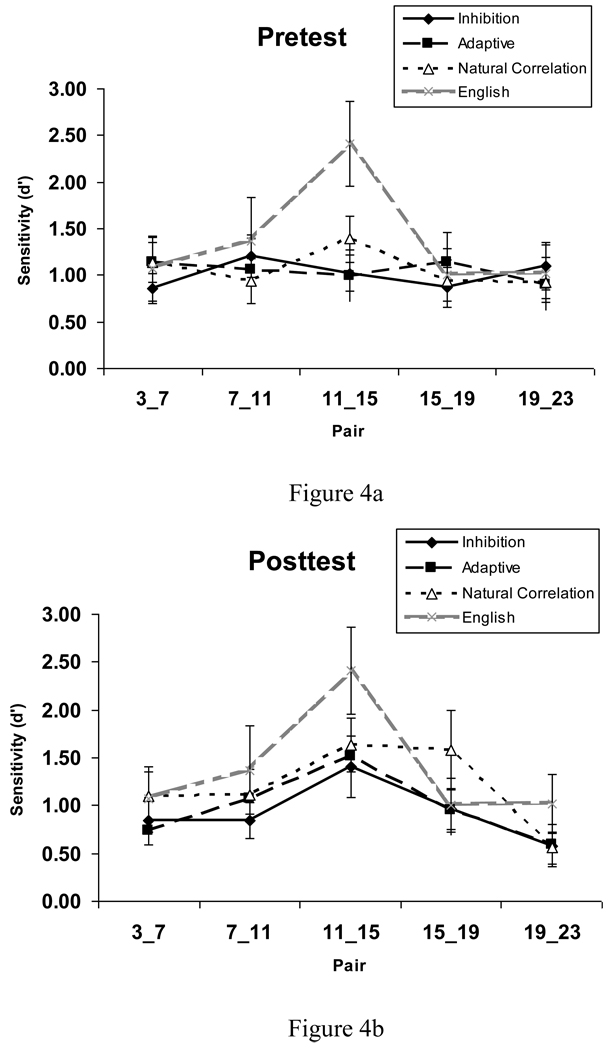

Pretest and posttest d’ scores averaged for each group of listeners are shown in Figure 3 (Duration) and Figure 4 (Spectrum) respectively. The same English listeners’d’ scores are repeated in the pretest and posttest graphs.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity (d’) along the Duration dimension on the (a) pretest and (b) posttest. Note that English listeners’ scores are repeated in each graph for reference.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity (d’) along the Spectrum dimension on the (a) pretest and (b) posttest. Note that English listeners’ scores are repeated in each graph for reference.

Duration

In order to examine whether d’ was different between any pair in any group, that would suggest a category boundary location, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between group factor, Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) and one within group factor, Pair (Pair 0_2, Pair 2_4, Pair 4_6, Pair 6_8, Pair 8_10) was run on d’ scores for duration on the pretest and posttest. On the pretest, results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 1.2, p = 0.322, or Pair, F (4, 140) = 1.94, p = 0.1 and no significant interaction between Pair and Group, F (12, 140) =0.41, p = 0.95 suggesting that listeners in each group were equally sensitive to differences between every pair.

On the posttest, results demonstrated no effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 0.23, p = 0.87, a significant effect of Pair, F (4, 140) = 4.30, p = 0.002, and no interaction between Pair and Group, F (12, 140) = 0.66, p = 0.78. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrated a significant difference in d’ scores between pair 8_10 (M = 0.57, SD = 0.1) and pair 4_6 (M = 0.52, SD = 0.07), p = 0.04, between pair 8_10 and pair 2_4 (M = 0.52, SD = 0.05), p = 0.02, and pair 8_10 and pair 0_2, (M = 0.5, SD = 0.05), p < 0.001. As pair 8_10 is found at the end of the testing continuum relative to other pairs, it is unlikely that the increased d’ score at this pair results from the location of a category boundary. Rather, it may be related to a psychophysical anchoring effect associated with continuum endpoints (Macmillan, 1986). Consequently, the source of this difference and will not be investigated further.

Pretest vs. Posttest. Duration

In order to compare changes in d’ from pretest to posttest, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between- group factor, Group (Inhibition, Adaptive, Natural Correlation) and two within-groups factors, Session (Pretest, Posttest) and Pair (Pair 0_2, Pair 2_4, Pair 4_6, Pair 6_8, Pair 8_10) were run on pretest versus posttest d’ scores. The results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.9, p = 0.38, no significant effect of Session, F (1, 26) = 0.04, p = 0.83, but a significant effect of Pair, F (4, 104) = 3.21, p = 0.01. No significant interactions (Session×Group, Pair×Group, Session×Pair or Session×Pair×Group) were found, suggested that there were no changes in mean d’ scores depending on the session. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) comparing pair means demonstrated a significant difference, p = 0.01 between pair 8_10 (M = 0.56, SD = 0.09) and 0_2 (M = 0.51, SD = 0.05) and a significant difference, p = 0.04 between pair 8_10 and pair 2_4 (M = 0.51, SD = 0.05).

Pretest: Spectrum

First, in order to examine whether d’ was different between any pair in any group, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between-group factor, Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) and one within-group factor, Pair (Pair 3_7, Pair 7_11, Pair 11_15, Pair 15_19, Pair 19_23) was run on d’ scores for spectrum.

Results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 1.28, p = 0.29, a significant effect of Pair, F (4, 140) = 2.88, p = 0.02, and no interaction between Pair and Group, F (12, 140) = 1.52, p = 0.12. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrated a significant difference in d’ scores between pair 11_15 (M = 1.47, SD = 1.05) and pair 15_19 (M = 1.01, SD = 0.75), p = 0.04, and between pair 11_15 and pair 19_23 (M = 0.95, SD = 0.74), p = 0.01, suggesting the location of category boundary was at pair 11_15.

The visual analysis of d’ scores along the spectrum dimension (Figure 5), however, suggested that, in the English group, (a) sensitivity to pair 11_15 was different from that in other pairs, implying the presence of a category boundary along the spectral dimension. As repeated measures analysis compares overall means taking into consideration all three groups in a model, this type of analysis can obscure the actual data when the aim is to find whether there is a difference in only one level (e.g. pair 11_15) as compared to all other levels (e.g. all other pairs) in each group. As a result, it was decided to run a one-way ANOVA with one between-group factor Pair (Pair 3_7, Pair 7_11, Pair 11_15, Pair 15_19, Pair 19_23) separately for each group to examine whether d’ measure is different between any pairs.

Figure 5.

Native Spanish and English spectrally-tuned (Beta Spec) and duration-tuned (Beta Dur) logistic regression coefficients on the pre- and posttest Identification Task (beat-bit set).

The results demonstrated that, as expected, there was a significant effect of Pair in the English group, F (4, 45) = 3.11, p = 0.02 with Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrating a significant difference between pair 11_15 (M = 2.41 , SD = 1.38) and pair 15_19 (M = 1, SD = 0.84), p = 0.03, between pair 11_15 and pair 19_23 (M = 1.02, SD = 0.9), p = 0.04, and between pair 11_15 and pair 3_7 (M = 1.07 , SD = 1.02), p = 0.05. These results suggest the location of a category boundary along spectral dimension at pair 11_15 in the English group. However, there was no significant effect of Pair in any other group (Inhibition, F (4, 40) = 0.4, p = 0.74; Adaptive, F (4, 45) = 0.34, p = 0.84; Natural Correlation, F (4, 45) = 0.7, p = 0.59) suggesting that there was no category boundary in any native Spanish group along the spectrum dimension.

Next, in order to examine whether d’ scores for pair 11_15 were different for the English as compared to the three Spanish training groups, a one-way ANOVA with one between group factor Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training and Natural Correlation) was run on d’ for pair 11_15 alone. This analysis demonstrated a significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 4.71, p = 0.007. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) showed a significant difference between the English group (M = 2.41, SD = 1.38) and each of the three Spanish groups (Inhibition (M = 1.02, SD = 0.58), p = 0.01; Adaptive (M = 0.99, SD = 0.83), p = 0.01, Natural Correlation (M = 1.39, SD = 0.76), p = 0.05), suggesting that English listeners were indeed more sensitive to the differences between the two members of this pair than were any of the Spanish listeners.

Posttest: Spectrum

On the posttest, the same repeated measures ANOVA with one between-group factor, Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) and one within-group factor, Pair (Pair 3_7, Pair 7_11, Pair 11_15, Pair 15_19, Pair 19_23) was run in order to examine whether d’ scores were different between any pair in any group. For the English group, d’ scores from pretest were employed in this analyses.

Results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 1.24, p = 0.3, a significant effect of Pair, F (4,140) = 12.85, p < 0.01 and no interaction between Pair and Group, F (12, 140) = 1, p = 0.44. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrated a significant difference in d’ scores between pair 11_15 (M = 1.79, SD = 1.06) and all other pairs (pair 3_7 (M = 0.93, SD = 0.71), p < 0.001, pair 7_11 (M =1.11, SD = 0.89), p < 0.001, pair 15_19 (M = 1.12, SD = 0.87), p < 0.001, and pair 19_23 (M = 0.68, SD = 0.63), p < 0.001) suggesting that the location of a category boundary was at pair 11_15 as indicated by increased d’ scores.

Next, one-way ANOVAs with one between-group factor Pair (Pair 3_7, Pair 7_11 Pair 11_15, Pair 15_19, Pair 19_23) were run separately for each group to examine whether d’ scores were different between any pairs in each separate Spanish training group. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Pair only in the Adaptive group, F (4, 45) =4.53, p = 0.003, with Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrating a difference in d’ scores in pair 11_15 (M = 1.51, SD = 0.57) and pair 3_7 (M = 0.74, SD = 0.37), p = 0.01, and pair 11_15 and pair 19_23 (M = 0.59, SD = 0.37), p = 0.002. There was also a marginally significant effect of Pair in the Natural Correlation group, F (4, 45) = 2.16, p = 0.08 with Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) demonstrating a marginally significant difference between pair 11_15 (M = 1.63, SD = 0.85) and 19_23 (M = 0.56 , SD = 0.51), p = 0.09. However, there was no significant effect of Pair in the Inhibition group, F (4, 40) = 1.61, p = 0.18. Overall, these results suggest that, at posttest, elevated d’ scores at pair 11_15, which indicate the category boundary location along the spectral dimension were found only in the Adaptive group and (with marginal significance) the Natural Correlation group.

In addition, in order to examine whether d’ scores for pair 11_15 were different for the English as compared to the three Spanish training groups a one-way ANOVA with one between group factor Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training and Natural Correlation) was run on d’ scores at pair 11_15 only. In contrast to the pretest, results now showed no significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 1.84, p = 0.15, suggesting that the d’ at pair 11_15 no longer differed between the English group and any of the Spanish training groups.

Pretest vs. Posttest. Spectrum

Finally, in order to compare changes in d’ from pretest to posttest, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between- group factor, Group (Inhibition, Adaptive, Natural Correlation) and two within-groups factors, Session (Pretest, Posttest) and Pair (Pair 3_7, Pair 7_11, Pair 11_15, Pair 15_19, Pair 19_23) was run on pretest versus posttest d’ scores. The results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.3, p = 0.7, no significant effect of Session, F (1, 26) = 0.01, p = 0.9, but a significant effect of Pair, F (4, 104) = 4.95, p = 0.00. Results of a Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) comparing overall d’ pair means (effect of Pair) demonstrated that there was a significant difference, p = 0.03, between pair 11_15 (M = 1.36, SD = 0.84) and pair 3_7 (M = 0.96, SD = 0.63) and a significant difference, p < 0.001, between pair 11_15 and pair 19_23 (M = 0.74, SD = 0.63). There was also a significant Session×Pair interaction, F (4, 104) = 4.16, p = 0.003, suggesting that mean d’ scores in some pairs were different and the difference in mean d’ scores depended on the session. No other interactions (Session×Group, Pair×Group, Session×Pair×Group) were significant. As the Session×Pair interaction was significant, further analysis was conducted. However, because the only comparison of apriori interest were changes from pretest to posttest, planned comparisons of means (α-level = 0.05/5 = 0.01 after Bonferroni correction) were conducted in order to examine changes in d’ scores in pairs 3_7, 7_11, 11_15, 15_19 and 19_23. The results demonstrated that there was a marginally significant difference in d’ scores from pretest to posttest, F (1, 26) = 4.9, p = 0.03 in pair 11_15 (pretest: M = 1.16, SD = 0.74; posttest: M = 1.57, SD = 0.89) suggesting an increased sensitivity at this pair after training. There was also a marginally significant difference, F (1, 26) = 4.2, p = 0.04, in pair 19_23 (pretest: M = 0.93, SD = 0.71; posttest: M = 0.55, SD = 0.5) suggesting a decreased sensitivity at this pair after training.

In summary, the discrimination task results demonstrated that both in English and Spanish listeners the perceptual space was warped only along the spectral dimension (in English, due to native language experience and in Spanish due to short-term laboratory training). The results of the native Spanish group were unexpected because the identification results from the pretest suggested that duration was the only dimension employed by Spanish listeners for categorization, suggesting that they might exhibit a category boundary (i.e. heightened sensitivity to cross-boundary pairs in the discrimination task) along the duration dimension.

The discrimination results along spectral continuum demonstrated, that, unlike untrained native Spanish listeners, English participants had an increased sensitivity in the middle of the continuum suggesting a category-boundary effect on spectral difference due to their native language experience. However, after training some indication of changes in the perceptual space of Spanish listeners were found, manifested as an increase in d’ scores in pair 11_15 as compared to all other pairs and from pretest to posttest. These results suggest that trained listeners were beginning to develop a category boundary along the spectrum continuum between tense and lax vowels in a process of acquired distinctiveness. Simultaneously, a decrease in d’ scores in pair 19_23 from pretest to posttest was observed suggesting a decreased perceptual sensitivity after training in the process of acquired similarity.

The current analysis suggests that there was no difference between training methods in terms of the restructuring of perceptual space along both duration and spectrum dimensions. That is, the d’ scores did not differ between the groups along either dimension. However, given that the Adaptive and Natural Correlation groups showed a significant difference in d’ posttest scores for pair 11_15 along the spectrum dimension while the Inhibition group did not, it seems possible that the complete lack of variability along the spectrum in the Inhibition training condition may have reduced the effect of perceptual learning of the contrast along this dimension for this group, at least with respect to the development of a clear category boundary along it.

3.2.4 Transfer of Training

3.2.4.1. Beat-Bit Continuum

The same logistic regression analysis previously employed for the examination of Spanish and English listeners’ proportion of [I] responses in the sheep-ship set (see paragraph 3.2.2.) was used to analyze responses for the beat-bit set as well. Fig 5 provides a scatterplot of spectrum-based (β spec) and duration-based (β dur) coefficient values for each native Spanish listener (comparable to Figure 2). English listeners’ results are plotted for reference. Table 7 presents means and standard deviation for each group.

Table 7.

Mean values of spectrally-tuned (Beta Spectrum) and duration-tuned (Beta Duration) beta coefficients for native Spanish and English participants

| Beta Spectrum | s.d | Beta Duration | s.d. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | ||||

| Inhibition | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.16 |

| Adaptive | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| English | 0.68 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Posttest | ||||

| Inhibition | 0.34 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Adaptive | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

Results

The first question examined whether training resulted in the change of weighting of spectral and duration dimensions from pretest to posttest in each of the three groups. For each group, a repeated measures ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation) and one within-group factor Test (Pretest, Posttest) was run on spectrally- and duration-tuned beta coefficients. Along the spectrum dimension, results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.04, p = 0.95, a significant effect of Test, F (1, 26) = 27.12, p < 0.001, and no Group×Test interaction, F (2, 26) = 0.08, suggesting an increase in the perceptual weighting of the spectral dimension after training in each group. Along the duration dimension, results demonstrated no significant effect of Group, F (2, 26) = 0.008, p = 0.99, a significant effect of Test, F (1, 26) = 21.06, p < 0.001 and no significant Group×Test interaction, F (2, 26) = 0.84, p = 0.44 suggesting a decrease in the perceptual weighting of the duration dimension after training in each group. It is worth noting that additional two-tailed t-tests examining changes in duration-tuned beta coefficients from pretest to posttest separately in each of the three groups demonstrated a significant difference between pretest and posttest coefficient values only for the Inhibition, t (16) = 2.11, p = 0.006 and Adaptive, t (18) = 2.11, p = 0.009, but not for the Natural Correlation group t (18) = 2.1, p = 0.14. These results are comparable to those conducted on the sheep-ship data.

The second question investigated which training method resulted in better transfer to a new phonetic environment. First, a one-way ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive, Natural Correlation) was run on the difference scores between spectrum-tuned beta-coefficients at posttest and pretest (see Table 8). The results demonstrated that there was no effect of Group between mean difference scores for spectrum-based beta-coefficients, F (2,26) = 0.08, p = 0.91, suggesting that the transfer of training resulted in the increase of attention to spectral properties in all three training groups, regardless of the training method. Next, as there was a trend suggested by separate t-tests that only Inhibition and Adaptive groups demonstrated a change between pretest and posttest coefficient values, a two-tailed t-test with one between-group factor Group (Inhibition, Adaptive) was run on the difference scores only in these groups. The results demonstrated no significant difference between Inhibition and Adaptive difference scores for duration-tuned beta-coefficients, t (17) = 2.1, p = 0.91 suggesting that the transfer of training was comparable in both groups.

Table 8.

Mean difference scores of native Spanish participants between spectrally-tuned (Beta Spectrum) and between duration-tuned (Beta Duration) coefficients at pretest and posttest

| Beta Spectrum | s.d | Beta Duration | s.d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.19 |

| Adaptive | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Natural Correlation | 0.21 | 0.22 |

In summary, results demonstrated a successful transfer of training to the perception of the same vowel in a new phonetic context for all three training groups along the spectral dimension. However, the type of the training seems to affect the degree of the generalization of learning along the duration dimension: Exposure to stimuli varying in two correlated dimensions, in the Natural Correlation group, resulted in poorer transfer to a new phonetic environment than in the other two groups.

Finally, in order to examine how the transfer of training affected native Spanish listeners’ responses in comparison to the English listener group, we compared their spectrally-tuned and duration-tuned beta-coefficients at both pretest and posttest using a one-way ANOVA with one between-group factor Group (English, Inhibition, Adaptive Training, Natural Correlation). At pretest, along the spectral dimension, there was a significant effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 32.2, p < 0.001 suggesting that mean values of spectrally-tuned coefficients were different in some groups. Planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.05/3 = 0.016 after Bonferroni correction) demonstrated a significant difference between the English group and every training group (Inhibition, F (1,35) = 59.26, p < 0.001; Adaptive Training, F (1, 35) = 67.86, p < 0.001, Natural Correlation, F (1,35) = 64.13, p < 0.001) suggesting that, before training, Spanish listeners relied on spectrum to a lesser extent than did native English listeners. Along the duration dimension, results also demonstrated a significant effect of Group F (3,35) = 3.15, p = 0.03 with planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.016) showing a significant difference between the English and the Inhibition groups, F (1,35) = 6.4, p = 0.01, and between the English and the Adaptive Training group, F (1,35) = 7.54, p = 0.009, and a marginally significant difference between the English and the Natural Correlation group, F (1,35) = 3.64, p = 0.06. These results suggest that all three training groups weighted the duration dimension to a greater extent than native English listeners before the training started.

At posttest, there was an effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 4.75, p = 0.006 for spectrally-tuned beta coefficients suggesting that there was a difference in the perceptual weighting of spectral dimension in some groups. Planned comparison of means (α-level = 0.016) showed a significant difference between English and Inhibition, F (1,35) = 8.54, p = 0.006, English and Adaptive, F (1,35) = 9.04, p = 0.004, and English and Natural Correlation, F (1,35) = 10.56, p = 0.002 groups. These results imply that although native Spanish listeners increased their attention to spectral properties as demonstrated by an increase in difference scores, it was not enough to transfer it to a new beat-bit set in the same manner as in the sheep-ship set as they were still different from native English listeners. For the duration dimension, however, there was no effect of Group, F (3, 35) = 0.4, p = 0.74 suggesting that all training groups decreased reliance on duration in the new beta-bit set and were not different from native English listeners.

3.2.4.2. Natural Words

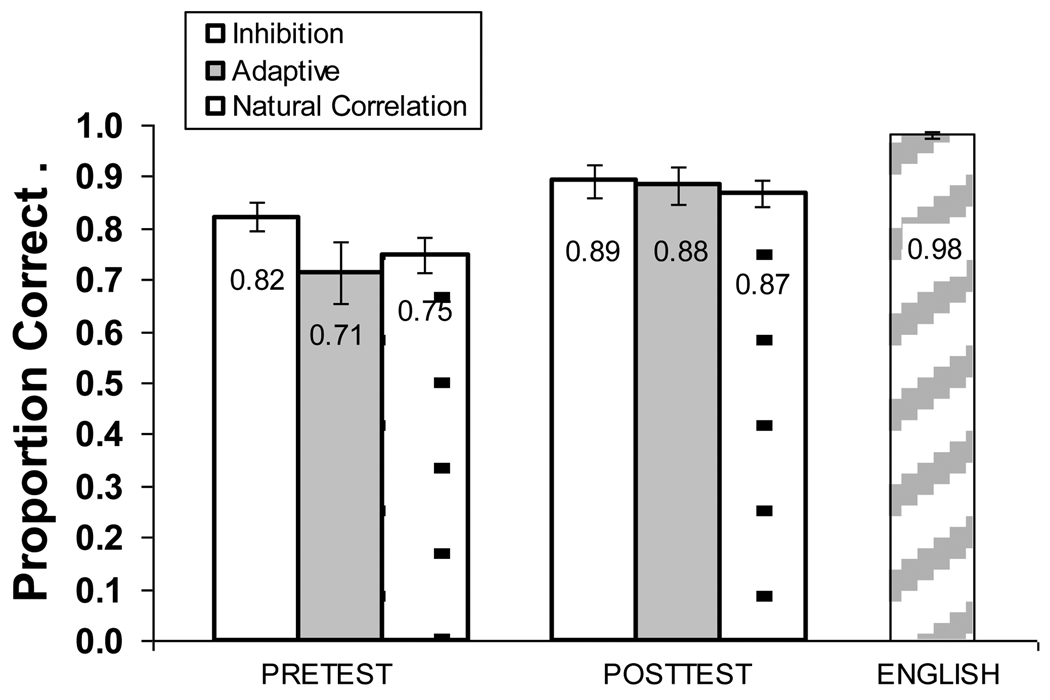

In order to determine whether training transferred to natural words, proportion of correct responses to all naturally produced words was calculated for each listener and averaged within groups (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proportion correct in the identification of naturally produced words with tense and lax vowel for each of the three training groups and the native English comparison group. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

A one-way ANOVA with one between group factor Group (English, Inhibition ,Adaptive Training and Natural Correlation) was run on the proportion of correct responses given to all words on the pretest. Results showed a significant effect of Group, F (3,35) = 10, p < 0.001 with Post Hoc tests (Tukey HSD) demonstrating a difference between the English (M = 0.98, SD = 0.02) and Inhibition (M = 0.82, SD = 0.08), p = 0.02, groups, between the English and the Adaptive Training (M = 0.71, SD = 0.19), p < 0.001, groups, and between the English and the Natural Correlation groups (M = 0.75, SD = 0.11), p < 0.001. However, there were no differences between the three training groups on the pretest.

Similarly, a one-way ANOVA of the posttest results demonstrated a significant effect of Group, F (3,35) = 3.52, p = 0.02 suggesting that there was a difference in the proportion of correct responses between some groups. Post Hoc analysis (Tukey HSD) revealed a significant difference between the English and Natural Correlation groups (M = 0.87, SD = 0.08), p = 0.02, and a marginally significant difference between the English and the Adaptive Training groups (M = 0.88, SD = 0.12), p = 0.07, but no difference between the English and the Inhibition groups (M = 0.89, SD = 0.1) groups, p = 0.13. There was also no difference in posttest scores between the three training groups.