Abstract

A five-step total synthesis of the antibiotic marinopyrrole A (1) is described. The developed synthetic technology enabled the synthesis of several marinopyrrole A analogues whose antibacterial properties against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus TCH1516 were evaluated.

Keywords: marine natural products, total synthesis, atropisomers, Clauson-Kaas reaction

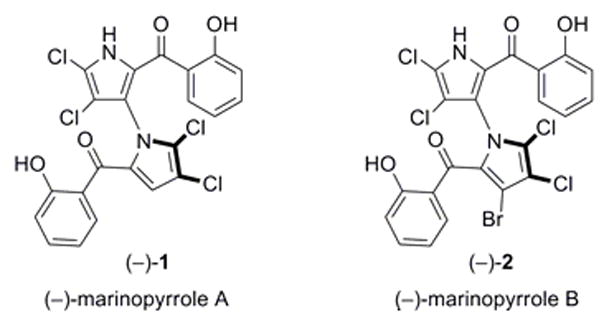

Marinopyrroles A and B (1 and 2, Figure 1) are two recently reported alkaloids endowed with promising antibiotic activities against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1 Isolated from an obligate marine Streptomyces (strain CNQ-418, collected from the sea floor near La Jolla, CA), these structurally unusual molecules exist as enantiopure M-(−)-atropisomers at ambient temperature. The absolute structure of (−)-2 was established through X-ray crystallographic analysis, and (−)-1 through spectroscopic comparisons. Due to their novel molecular structures and promising biological properties, the marinopyrroles have attracted significant attention. The preparation of several semisynthetic analogues,2 a study of the mode of action,3 and a total synthesis4 of marinopyrrole A [(±)-1] have been reported. A recent evaluation of the pharmacological properties of marinopyrrole A revealed potent anti-MRSA activity and favorable in vitro kinetics.5 We set out to develop a total synthesis that could deliver large amounts of material and would be flexible enough to allow construction of a wide range of analogues for probing structure–activity relationships (SARs). We report herein a short and efficient total synthesis of marinopyrrole A (1) and a series of analogues, as well as their biological evaluation.

Figure 1.

Marinopyrroles A (1) and B (2).

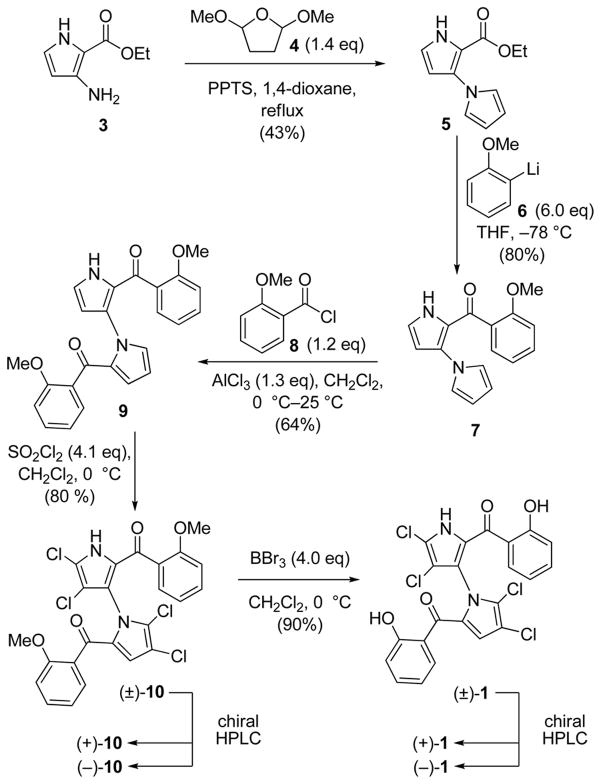

Although a direct, late-stage dimerization of two fully elaborated pyrrole units could be imagined, such a route might be limiting in terms of substrate scope and coupling efficiency. An alternative approach involving early construction of the bis-pyrrole system followed by site-specific introduction of the benzenoid rings and chlorine residues would allow easy access to a variety of designed analogues. Scheme 1 summarizes the developed five-step route to marinopyrrole (−)-1 (natural) and (+)-1 (unnatural) from the readily available building blocks aminopyrrole 36 and 2,5-dimethoxytetrahydrofuran (4; commercially available). Thus, a PPTS-promoted Clauson-Kaas reaction7 between 3 and 4 in refluxing 1,4-dioxane furnished bis-pyrrole 5 in 43% yield, establishing the crucial C–N bond. The latter compound underwent smooth mono-addition of lithiated anisole 6, in THF at −78 °C, to afford tricycle 7 in 80% yield. Friedel–Crafts arylation of 7 with acid chloride 8, mediated by AlCl3 in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C, led to the marinopyrrole core structure 9 in 64% yield. Despite multiple potential chlorination sites, compound 9 underwent selective pyrrole tetra-chlorination with 4.1 equivalents of sulfuryl chloride8 (SO2Cl2) in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C to generate dimethyl marinopyrrole A derivative (±)-10 in 80% yield.4 Exposure of tetrachloride (±)-10 to additional SO2Cl2 or other chlorination reagents [e.g. N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS)] led to para-chlorination of the aryl moieties. Similarly, attempts to brominate the remaining pyrrole position to prepare methyl-protected (±)-2 led only to para-bromination of the aryl rings. That compound 10 exists as two stable atropisomers was confirmed by chiral HPLC separation (4:1 hexanes:i-PrOH, Chiralcel® OD-H) of the two enantiomers [(+)-10 and (−)-10]. These enantiomers demonstrated remarkable thermal stability, showing no detectable racemization in DMF at 120 °C after 24 h. In contrast, marinopyrrole A (1) racemizes completely at that temperature.2 Finally, cleavage of the methyl ethers of (±)-10 (BBr3, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 90% yield) delivered racemic marinopyrrole A [(±)-1] in five steps and 16% overall yield from aminopyrrole 3. The two enantiomers of (±)-1 were separated by chiral HPLC under the published conditions (19:1 hexanes:i-PrOH, Chiralcel® OD-H)1 to afford (+)-1 and (−)-1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of marinopyrrole A [(+)-1 and (−)-1].

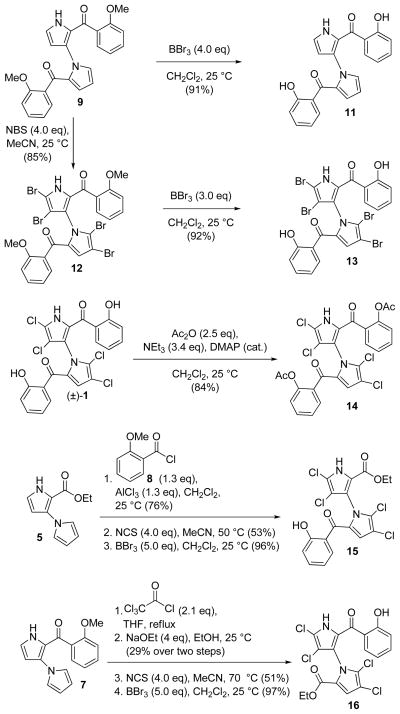

The developed technology for the total synthesis of marinopyrrole A was employed for the synthesis of designed analogues 11–16 as summarized in Scheme 2. Thus, demethylation of compound 9 (BBr3, CH2Cl2, 91% yield) gave dehalogenated marinopyrrole A 11.4 Treatment of bis-pyrrole 9 with 4.0 equivalents of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) led to selective tetra-bromination on the pyrrole rings to afford 12 in 85% yield. As observed with tetrachloride 10, exposure of 12 to further amounts of NBS led to para-bromination of the aryl moieties. Compound 12 was then demethylated (BBr3, CH2Cl2, 92% yield) to provide tetrabromomarinopyrrole 13. Acetylation of the phenolic oxygens of (±)-1 proceded readily with acetic anhydride and NEt3 in the presence of catalytic amounts of DMAP, furnishing diacetylmarinopyrrole A 14 in 84% yield.2,3 Mono-arylated marinopyrrole 15 was prepared from bis-pyrrole 5 through a three-step sequence involving a Friedel–Crafts C-arylation with acid chloride 8, tetra-chlorination with NCS in MeCN at 50 °C, and demethylation with BBr3 in CH2Cl2 to afford 15 in 39% overall yield. Similarly, 16 was prepared from 7 in 14% overall yield though a four-step sequence involving C- C-acetylation with trichloroacetylchloride in refluxing THF, trichloromethyl displacement with NaOEt in EtOH, tetra-chlorination (NCS, MeCN, 70 °C), and cleavage of the methyl ethers (BBr3, CH2Cl2). Although compounds 12–16 likely exist as enantiomeric atropisomers stable at room temperature, no chiral HPLC separation was undertaken prior to their testing due to the potency equivalence of the two marinopyrrole A enantiomers (see Table 1, entries 2 and 3).1

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of marinopyrrole A analogues 11–16.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of synthetic marinopyrroles.

| Entry | compound | MIC50a (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (±)-1 | 0.375–0.750 |

| 2 | (+)-1 | 0.189 |

| 3 | (−)-1 | 0.189 |

| 4 | 9 | >96 |

| 5 | (±)-10 | >96 |

| 6 | 11 | 48 |

| 7 | 12 | >96 |

| 8 | 13 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 14 | 0.375 |

| 10 | 15 | 3 |

| 11 | 16 | 1.5 |

Tested against MRSA TCH1516 (ATCC BAA-1717)

The synthesized compounds [(±)-1, (+)-1, (−)-1, and 9, (±)-10, and 11–16] were evaluated for their antibacterial activities against TCH1516, a strain representative of the current epidemic clone of community-acquired MRSA.5 The results are shown in Table 1. Thus, synthetic racemic [(±)-1] and enantiopure [(+)-1 and (−)-1] marinopyrroles (entries 1–3) exhibited antibacterial potencies comparable to those of their naturally-derived counterparts.1 Interestingly, the tetrabrominated congener of marinopyrrole A 13 (entry 8) exhibited comparable potency to marinopyrrole A, while the dehalogenated analogue 11 (entry 6) was significantly less active, indicating the importance of the halogen atoms for biological activity. It was also clear that the free phenolic groups were necessary for activity since dimethylated marinopyrrole derivatives [9, (±)-10, and 12] showed no activity (entries 4, 5 and 7, respectively). bis-Acetylated marinopyrrole 14 (entry 9) showed similar antibacterial potency to marinopyrrole [(±)-1] itself, possibly due to in situ ester hydrolysis within the cell. Excision of one of the two phenolic rings from the marinopyrrole structure led to active, but less potent analogues, as demonstrated by compounds 15 and 16 (entries 10 and 11, respectively). When these compounds were tested in the same assay, but in the presence of 20% normal pooled human serum, they were found to be devoid of antibacterial properties, presumably due to protein adsorption.

In summary, a concise total synthesis of marinopyrrole A (1) that allows for large scale preparation of this novel natural product and its analogues is reported. The synthesized compounds were evaluated for activity against the clinically-important USA 300 clone of MRSA, with several showing strong antibacterial potencies. However, all suffered complete loss of antibacterial activity in the presence of human serum, suggesting utility in topical but not systemic formulations. Further structural modifications, including the design of prodrug-like compounds, may be necessary in order to improve the pharmacological profile of the marinopyrroles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, a National Institutes of Health (U.S.A.) grant and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) (to N.M.H.), and a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship (to N.L.S.).

Footnotes

Further experimental details for the synthesis and biological evaluation of compounds as well as selected physical properties of compounds can be found, in the online version, at doi:---.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Hughes CC, Prieto-Davo A, Jensen PR, Fenical W. Org Lett. 2008;10:629. doi: 10.1021/ol702952n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes CC, Kauffman CA, Jensen PR, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3240. doi: 10.1021/jo1002054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes CC, Yang YL, Liu WT, Dorrestein PC, La Clair JJ, Fenical W. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12094. doi: 10.1021/ja903149u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng C, Pan L, Chen Y, Song H, Qin Y, Li R. J Comb Chem. 2010;12:541. doi: 10.1021/cc100052j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haste NM, Hughes CC, Tran DN, Fenical W, Jensen PR, Nizet V, Hensler ME. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother; In submission. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furneaux RH, Tyler PC. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8411. doi: 10.1021/jo990903e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochais C, Lisowski V, Dallemagne P, Rault S. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:8162. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikuchi H, Sekiya M, Katou Y, Ueda K, Kabeya T, Kurata S, Oshima Y. Org Lett. 2009;11:1693. doi: 10.1021/ol9002306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.