Abstract

Breast cancer frequently metastasizes to bone, where tumor cells receive signals from the bone marrow microenvironment. One relevant factor is TGF-β, which up regulates expression of the Hedgehog (Hh) signaling molecule Gli2 which in turn increases secretion of important osteolytic factors such as parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP). PTHrP inhibition can prevent tumor-induced bone destruction, whereas Gli2 over expression in tumor cells can promote osteolysis. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that Hh inhibition in bone metastatic breast cancer would decrease PTHrP expression and therefore osteolytic bone destruction. However, when mice engrafted with human MDA-231 breast cancer cells were treated with the Hh receptor antagonist cyclopamine, we observed no effect on tumor burden or bone destruction. In vitro analyses revealed that osteolytic tumor cells lack expression of the Hh receptor, Smoothened, suggesting an Hh-independent mechanism of Gli2 regulation. Blocking Gli signaling in metastatic breast cancer cells with a Gli2-Repressor gene (Gli2-Rep) reduced endogenous and TGF-β-stimulated PTHrP mRNA expression, but did not alter tumor cell proliferation. Furthermore, mice inoculated with Gli2-Rep-expressing cells exhibited a decrease in osteolysis, suggesting that Gli2 inhibition may block TGF-β propagation of a vicious osteolytic cycle in this MDA-231 model of bone metastasis. Accordingly, in the absence of TGF-β signaling, Gli2 expression was down regulated in cells, whereas enforced over expression ofGli2 restored PTHrP activity. Taken together, our findings suggest that Gli2 is required for TGF-β to stimulate PTHrP expression, and that blocking Hh-independent Gli2 activity will inhibit tumor-induced bone destruction.

Keywords: Gli, PTHrP, Osteolysis, Breast cancer, Hedgehog, Cyclopamine, Bone Metastasis

Introduction

Despite advances in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer, it remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women (2009, ACS Cancer Facts & Figures), which is in part due to its propensity to metastasize to distant organs such as lung and bone. Breast cancer patients who develop bone metastases suffer increased morbidity and mortality, with increased fracture risk and the possibility of hypercalcemia among other complications (1, 2). Although survival rates among breast cancer patients with controlled local disease remain high, patients with advanced disease suffer from a 71% decrease in survival (3). Therefore, it is critical that new approaches be generated for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer metastasis to bone.

Breast cancer metastasis to bone begins with initiation of a “vicious cycle” of bone destruction, commencing upon tumor cell establishment in the bone marrow and resulting in increased bone resorption, or osteolysis. Tumor cells receive signals from the bone marrow environment (e.g. transforming growth factor-β; TGF- β), which up-regulates expression of the Hedgehog signaling transcription factor, Gli2, and leads to increased expression and secretion of the osteolytic factor parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP)(3). PTHrP propagates the vicious cycle via PTH-receptor binding on osteoblasts, leading to increased RANKL expression, which induces osteoclastogenesis. As the bone is resorbed, active TGF-β is released from the bone matrix stimulating further tumor growth and PTHrP expression (4). Inhibition at any point in this process should reduce bone destruction. For example, neutralizing antibodies against tumor production of PTHrP inhibits osteolytic bone destruction and tumor burden in vivo (5, 6). While a humanized anti-PTHrP antibody was developed in 2003, no official report has been made about the success of this antibody in patients (7, 8). Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that the Hedgehog signaling transcription factor Gli2 positively regulates PTHrP expression and secretion in osteolytic breast tumor cells (9).

Canonical Hedgehog (Hh) signaling occurs through Hh ligand binding to the membrane receptor Patched (Ptc), which releases inhibition of a second membrane receptor, Smoothened (Smo). This release initiates a downstream signaling cascade resulting in translocation of the Gli family proteins to the nucleus, where they can initiate transcription (10). Gli protein activation has been demonstrated in numerous tumor types and results from a variety of mutations that occur throughout the Hedgehog signaling pathway (11). In these tumor types, Hh receptor antagonists like cyclopamine have been used successfully to prevent Gli over-expression (12).

While all Gli family members bind to the same binding sequence, they have separate and discrete functions in mammalian cells (13). We have shown that Gli2, but not the other Gli family members, enhances PTHrP expression. Furthermore, expression of Gli2 appears limited to tumor cells that have high metastatic potential, especially to bone resulting in osteolytic lesions (9).

Taken together these data suggest that inhibition of Gli2 is a potential target for the development of therapeutics aimed at preventing and treating bone metastases. Therefore, we hypothesized that inhibition of Gli2 in bone metastatic lines would decrease PTHrP expression and therefore osteolytic lesions.

Materials and Methods

Cells

The human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 was obtained from ATCC and a bone metastatic variant generated in our lab was used for all in vitro and in vivo experiments, as previously published (5, 9). MDA-MB-231 cells, the human squamous non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line RWGT2 (14), and human metastatic prostate cancer cell line PC3 (ATCC), were maintained in DMEM (Cell-gro) plus 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Mediatech). The murine chondrocyte cell line TMC23 and human non-osteolytic breast cancer cell line MCF-7 were cultured in α-MEM (Invitrogen) plus 10% FBS and 1% P/S. All cell lines are routinely tested for changes in cell growth and gene expression. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with either Gli2-His, GFP, pcDNA (empty vector) or Gli2-Rep, by Lipofectamine transfection reagent and Plus reagent (Invitrogen), per manufacturer’s instructions, and stable cell lines were selected for antibiotic resistance into single cell clones by limiting dilutions or pooled colonies under 400μg/ml G418 selection medium and maintained in culture medium supplemented with 200μg/ml G418.

Animals

All animal protocols were approved by Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted according to NIH guidelines. Female, 4-week old athymic nude mice (n=8, vehicle; n=13, cyclopamine and n=10, empty vector; n=7, Gli2-Rep) were anesthetized by continuous isoflurane and inoculated with 100,000 MDA-MB-231, MDA-231-cntrl, or MDA-231-Gli2-Rep cells re-suspended in PBS via intracardiac injection into the left cardiac ventricle using a 27-gauge needle, as previously described (9, 15, 16). Mice were imaged weekly and sacrificed 4 weeks post-tumor cell inoculation. For mammary fat pad injections, female4-week old athymic nude mice (n=8/group) were anesthetized by continuous isoflurane and an incision was made on the ventral lower abdomen. The left inguinal mammary gland was inoculated with 1,000,000 MDA-231-Gli2-Rep or MDA-231-cntrl cells re-suspended in PBS. Tumor size was assessed by caliper measurements twice per week. Mice were sacrificed three weeks after tumor cell inoculation, and tumors excised, measured, and weighed.

Radiographic Imaging

Mice were radiographically-imaged weekly beginning one-week post-tumor cell inoculation using a Faxitron LX-60. Specifically, mice were anesthetized deeply with ketamine/xylazine and laid in a prone position on the imaging platform. Images were acquired at 35 kVp for 8 seconds. Lesion area and number were measured using quantitative image analysis software (Metamorph, Molecular Devices, Inc.) by region of interest analysis. All data are represented as mean lesion area and number per mouse.

TGF-β/Cyclopamine Treatments

Cyclopamine (LC Labs) was re-constituted in (2-Hydroxypropyl)-beta-cyclodextrin solution 45% (w/v) in HOH (Sigma-Aldrich). Beginning two weeks post-tumor cell inoculation, mice were treated daily with either 10mg/kg cyclopamine or control tomatadine analog by i.p. injection, as previously published (12).. For in vitro studies, 1–10μM (with data from 3μM shown) cyclopamine or tomatadine was added to cell culture medium and cells were harvested 24 hours later. Recombinant TGF-β(R&D Systems, Inc) was re-constituted in 4mM HCl and 1mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), and added at 5ng/ml to cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (or as indicated in text).

Histology/Histomorphometry

Hind-limb specimens (tibiae and femora) were removed during autopsy and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific) for 48 hours at room temperature. Bone specimens were decalcified in 10% EDTA for 2 weeks at 4°C and embedded in paraffin. 5μm-thick sections of bone were stained with hematoxylin & eosin, orange G, and phloxine. Tumor burden in the femora and tibiae was examined under a microscope and quantified using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Inc.) and region of interest analysis.

Reverse-transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAgen), per manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) and random hexamers from 1–5μg of total RNA per manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA (1.0μl) was used for RT-PCR using Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was conducted for the human homologues of the Hedgehog signaling receptors Patched (Ptch) and Smoothened (Smo). Primers for amplifying hPtch are as follows: F, 5′-CGCCTATGCCTGTCTAACCATGC-3′; R, 5′-TAAATCCATGCTGAGAATTGCA-3′. PCR was performed on the Bio-Rad iCycler with the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 2min, (94°C for 30sec, 66°C for 1min, 72°C for 30sec) ×35 cycles, 72° for 2min. Primers for hSmo amplification are as follows: F, 5′-TTACCTTCAGCTGCCACTTCTACG-3′; R, 5′-GCCTTGGCAATCATCTTGCTCTTC-3′. PCR was performed with the following cycling conditions: 94°C for 4min, (94°C for 30sec, 56°C for 1min, 72°C for 45sec)×35 cycles, 72° for 2min.

Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR (Q-PCR)

PTHrP, Gli2, and 18s mRNA expression were measured by Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (Q-PCR). After 48hr incubation, cells were harvested for mRNA, and a complimentary DNA (cDNA) strand was generated as described above. cDNA was serially diluted to create a standard curve, and combined with TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and primer: TaqMan PTHLH (Hs00174969_m1), TaqMan Gli2 (Hs00257977_m1), or TaqMan Euk 18S rRNA (4352930-0910024; Applied Biosystems). Samples were loaded onto an optically clear 96-well plate (Applied Biosystems) and the Q-PCR reaction was performed under the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2min, 95°C for 10min, (95°C for 15sec, 60°C for 1min) x40 cycles on the 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Q-PCR reactions were quantified using the 7300 Real-Time PCR Systems software (Applied Biosystems).

Cell Proliferation Assay

In vitro cell proliferation was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Promega). Briefly, 2,000 cells/well were plated in 96-well plates in quadruplicate, and growth was measured at days indicated spectrophotometrically at 450nm on aSynergy2 plate reader, per manufacturer’s instructions.

Western Blot

Cells were harvested for protein into a 1X radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (ThermoScientific) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Roche). Equal protein concentrations were prepared for loading with Laemmli sample buffer and electrophoresis was performed on SDS-PAGE Mini-Protein II ready gels (Bio-Rad). Separated proteins were then transferred to Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) in transfer buffer [25 mmol/L Tris, 192 mmol/L glycine, 20% (v/v) methanol (pH 8.3)] at 100V at 4°C for 1 hour. Membranes were blocked with1XTBS buffer containing 1% Tween 20 (1XTBST) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with a 1:200 dilution of Omni-probe α-His antibody(Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in blocking buffer. The membrane was washed with 1XTBST and signal was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham). Membrane was stripped using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific), washed with 1XTBST, and re-probed with a 1:5000 dilution of β-actin antibody (Sigma) as a loading control.

Micro-Computed Tomography (MicroCT)

Tibiae were analyzed using the Scanco μT40. Specifically, 100 slices from the proximal tibia were scanned at 12 micron resolution. Images were analyzed using the Scanco Medical Imaging software to determine the Bone Volume/Total Volume (BV/TV), Trabecular Number and Thickness, and Connectivity Density.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using InStat version 3.03 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and p-values determined using unpaired t-test, where*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001unless otherwise stated.

Results

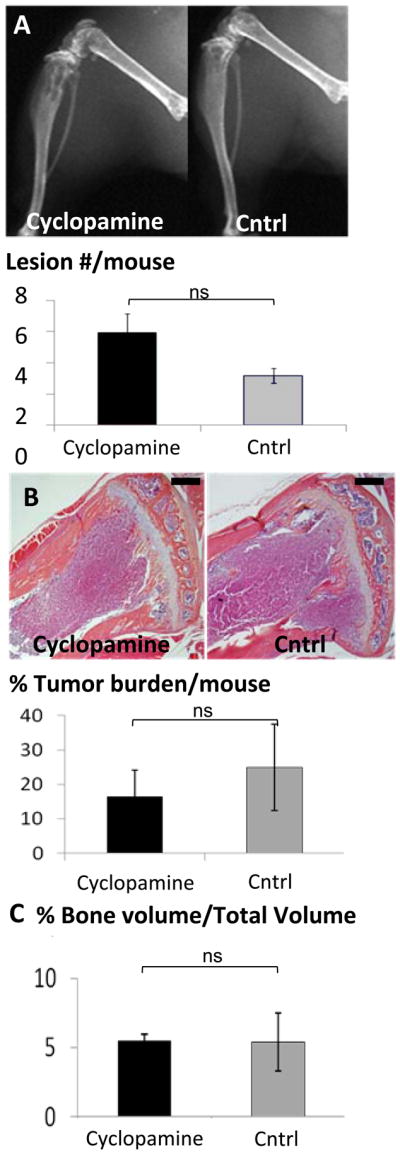

Cyclopamine treatment does not prevent tumor-induced bone destruction in vivo

Cyclopamine treatment has previously been reported to block Hh signaling and inhibit tumor growth in some in vivo models (17) through its action as a Smo antagonist (18). Therefore, we first proposed to determine the effects of cyclopamine treatment on osteolytic bone metastases. Mice inoculated with MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were treated with 10mg/kg cyclopamine or control tomatadine analog daily, beginning two weeks post-inoculation and after tumor cells had seeded to bone, similar to previously published treatment regimens which successfully inhibited tumor growth (19). Surprisingly, cyclopamine inhibited neither tumor growth nor cancer-induced bone disease in the bone metastasis model. Indeed, examination by radiography (Figure 1a) indicated that there was a slight increase in osteolytic lesion number in mice treated with cyclopamine when compared to tomatadine-treated mice. After sacrifice, bones were collected from tumor bearing mice from both treatment and control groups for histology and histomorphometry. Histologically, cyclopamine treatment had little or no effect on tumor burden in bone (Figure 1b) or trabecular bone volume at multiple sites commonly examined by histology (Figure 1c). It was concluded that the Hh receptor antagonist cyclopamine is ineffective treatment for osteolytic bone metastases in this experimental model of breast cancer-induced bone destruction.

Figure 1. Cyclopamine does not reduce osteolysis or tumor burden.

Mice were treated daily with 10mg/kg cyclopamine (n=13) or control tomatadine analog (n=8) and imaged radiographically weekly. (a) Faxitron analyses indicate no significant difference (ns) in lesion number in cyclopamine-treated versus non-treated mice. There was no significant (ns) change in (b) tumor burden detected by % tumor area, or (c) bone volume measured as trabecular bone volume/total volume; BV/TV, on histomorphometric analyses of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections. The black bar on the histological sections represents a length of 500μM. Values = mean ±standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p<0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

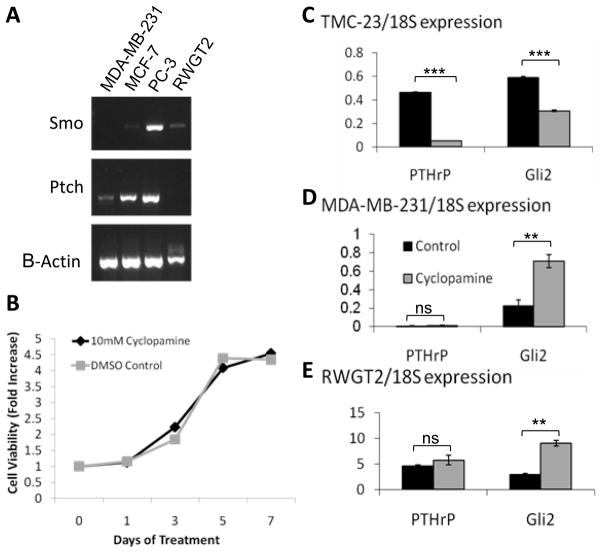

Canonical Hh signaling does not regulate Gli2 in MDA-MB-231 cells

To determine why MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells are not inhibited by cyclopamine, we next examined the expression of Hh signaling receptors. MDA-MB-231 cells, which express both Gli2 and PTHrP and are known to cause osteolysis, did not express Smo mRNA, and MCF-7 breast cancer cells (non-osteolytic) and RWGT2, a squamous non small cell lung carcinoma cell line, expressed low levels of Smo mRNA (Figure 2a). In contrast, PC-3 prostate cancer cells were found to express Smo mRNA, consistent with findings by another group that showed these cells are inhibited by cyclopamine (Figure 2a) (12).

Figure 2. Gli2 is regulated by a Hedgehog independent mechanism.

(a) PCR analyses -for Patched (ptch) and Smoothened (Smo) receptor expression in osteolytic and non-osteolytic cell lines show MDA-MB-231 cells do not express Smo. (b) MDA-MB-231 cells treated with 3 μM cyclopamine exhibit no significant (ns) difference in tumor cell growth by MTS assay. Tumor cells treated with 3μM cyclopamine (gray bars) were compared to control tomatadine treatment (black bars) and examined after 24hrsfor Gli2 and PTHrP mRNA expression by Q-PCR. (c) Chondrocyte cell line TMC-23,(d) MDA-MB-231, and (e) RWGT2 cells. Values = mean ± standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

Treatment ofMDA-MB-231 cells with cyclopamine in vitro did not alter tumor cell growth over a 7-day treatment period (Figure 2b), indicating that Hh signaling does not play a significant role in the growth of these cancer cells. RWGT2 cell growth was also not inhibited by cyclopamine, despite low levels of Smo expression (data not shown). We next examined cyclopamine-treated MDA-MB-231 and RWGT2 cells for PTHrP and Gli2 expression by Q-PCR. As a positive control, we also tested the cyclopamine-treated chondrocyte cell line, TMC-23. Blocking Hh signaling had no effect on PTHrP mRNA expression in either of the tumor cell lines, and cyclopamine treatment did not inhibit and in fact increased Gli2 mRNA in both the MDA-MB-231 and RWGT2 cells (Figure 2d&e). Since Hh signaling is known to regulate PTHrP expression in proliferating chondrocytes (20), we reasoned that TMC-23cells would be inhibited by cyclopamine, and as expected, PTHrP expression was indeed inhibited by cyclopamine treatment in TMC-23 cells (Figure 2c). Together, these data confirm that the compound was active and suggests that osteolytic tumor cells rely on an alternative mechanism for PTHrP expression. Thus, Hh signaling inhibition by cyclopamine appears ineffective towards breast tumor cell growth or expression of osteolytic factors by tumor cells, and we conclude that elevatedGli2 expression levels in MDA-MB-231 cells is not due to enhanced Hh signaling through the canonical pathway.

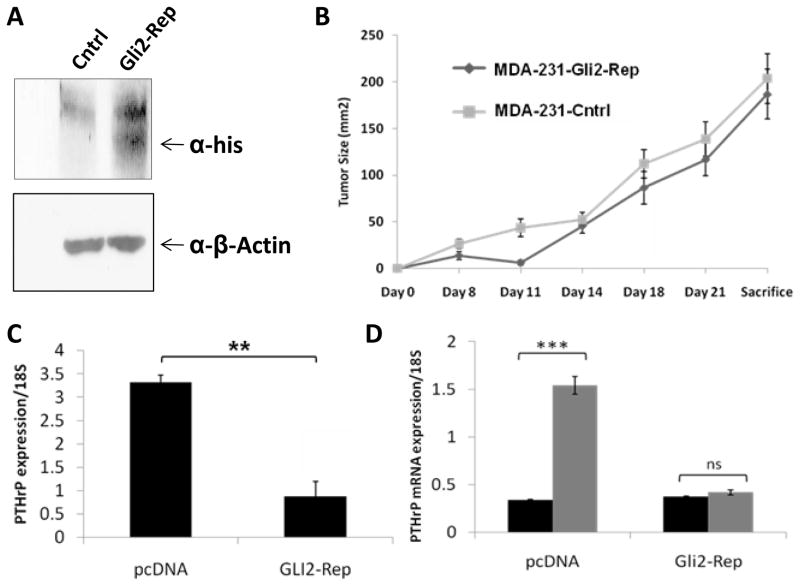

Gli2 inhibition in human bone metastatic breast cancer cells

Since cyclopamine treatment was ineffective at blocking downstream Gli2 expression in osteolytic tumor cells, targeted Gli2 inhibition was explored. To specifically inhibitGli2 expression, tumor cells were transfected with a Gli2-Repressor construct (Gli2-Rep) in which the activation domain of the Gli2 promoter has been replaced with the engrailed repressor domain as previously described (21). We have found that this construct efficiently knocks down Gli2 activity in vitro (9). After generating stable cell lines, positive cells were selected based on neomycin resistance, with both single cell clones and pools of transfectants generated. Because of concerns that single cell clones may result in a selection of a population with a constitutive decrease in PTHrP or a decrease or increase in aggressiveness, we focused on the pooled populations for these studies. However, similar results were obtained for all populations tested. Positive cells were screened for the expression of Gli2-Rep with an anti-His-tag antibody by Western blot (Figure 3a). Interestingly, expression of Gli2-Rep had no effect on tumor cell growth in vivo when cells were injected orthotopically into the mammary fat pad of athymic nude mice (Figure 3b). Consistent with our previous observation that Gli2 stimulates PTHrP expression, the expression of Gli2-Rep caused a reduction in endogenous PTHrP mRNA expression inMDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3c).

Figure 3. Gli2-Rep blocks downstream PTHrP, but not tumor growth directly.

Pooled populations of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with the Gli2-Rep construct and selected for antibiotic resistance were examined by (a) Western blot to verify efficient expression of Gli2-Rep. (b) MDA-231-Gli2-Rep (n=8)or MDA-231-cntrl (n=8) cells injected into the mammary fat pad of mice and sacrificed after3 weeks to determine tumor cell growth in vivo. (c) MDA-231-Gli2-Rep cells grown in culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and examined for PTHrP mRNA expression by Q-PCR have reduced PTHrP mRNA expression. (d) MDA-231-cntrl or MDA-231-Gli2-Repcells grown in serum free medium and treated with 5ng/mL exogenous TGF-β. Values = mean ± standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

Since others and we have previously shown that TGF-β stimulates Gli2 and PTHrP expression (9, 22, 23), we hypothesized that blocking Gli2 activity would inhibit the ability of TGF-β to increase PTHrP expression. We therefore treated MDA-231-Gli2-Rep cells and MDA-231-cntrl (empty vector-transfected) cells with 5ng/ml TGF-β in serum-free medium and measured PTHrP expression by Q-PCR. Inhibition ofGli2 activity completely blocked the TGF-β-induced increase in PTHrP expression (Figure 3d). Importantly, the basal level of PTHrP in MDA-MB-231 cells was not affected by Gli2 inhibition when cells were grown in serum free medium (Figure 3d), as compared to its effect on cells grown in 10% fetal bovine serum containing biologically active TGF-β (Figure 3c). Our data suggests that direct Gli2 inhibition can attenuate TGF-β induction of PTHrP, and thereby abrogate subsequent PTHrP-mediated bone destruction.

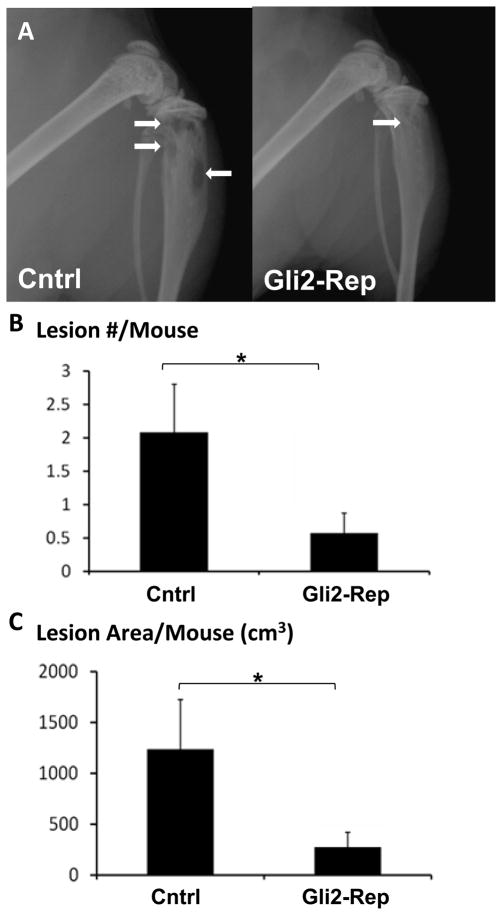

Gli2 Inhibition reduces tumor-mediated osteolytic bone destruction

In order to determine if blocking Gli2 activity could indeed inhibit tumor-induced osteolysis, we inoculated pooled MDA-231-Gli2-Rep and MDA-231-cntrl cells into athymic female nude mice via the left cardiac ventricle. After 4 weeks, extensive osteolytic lesions were visible radiographically in the femora/tibiae of the control mice. In contrast, the Gli2-Rep mice had either small or undetectable lesions (Figure 4a). Quantification of lesion number and size on radiographs indicated that mice bearing MDA-231-Gli2-Rep tumor cells had significantly fewer and smaller lytic lesions than the mice bearing control cells (Figure 4b&c). Similar results were obtained for mice inoculated with Gli2-Rep cells derived from single cell clones (Supplemental figure 1).

Figure 4. Gli2-Rep blocks tumor-induced bone disease.

Mice inoculated with MDA-231-Gli2-Rep (n=7) orMDA-231-cntrl (n=10) cells via intracardiac injection were imaged radiographically weekly. (a) Faxitron images depict fewer lesions in mice inoculated with MDA-231-Gli2-Rep cells. There was a significant reduction in average lesion number/mouse (b) and average lesion area/mouse(c), as measured by region of interest (ROI) analysis. Values = mean ± standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

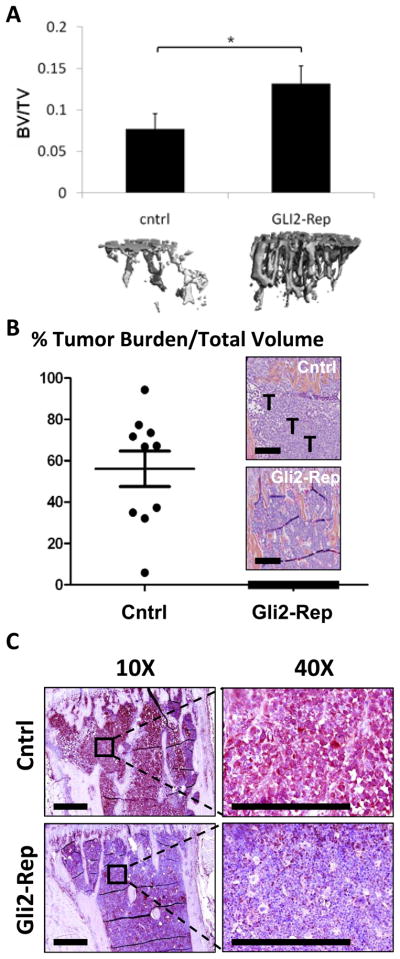

In addition to radiographic analyses, tibiae were examined by ex vivo microCT. There was a significant decrease in trabecular bone volume in the MDA-231-cntrl tumor bearing mice compared to the MDA-231-Gli2-Rep tumor bearing mice (Figure 5a), although there were no other significant changes in microCT parameters such as trabecular number, trabecular thickness, or connectivity density (Supplemental figure 2). Bone volume of mice inoculated with MDA-Gli2-Rep cells was not significantly different from non-tumor bearing age-and sex-matched mice (BV/TV approx. 0.0448-.1518). These data indicate that Gli2 inhibition in MDA-MB-231 cells decreased the ability of the tumor cells to induce bone destruction.

Figure 5. Gli2-Rep reduces osteolysis and tumor burden.

(a) Ex-vivo microCT (Scanco) analyses indicate a significant reduction in osteolysis in MDA-231-Gli2-Rep inoculated mice (n=7tibiae) compared to MDA-231-Cntrl inoculated mice (n=10 tibiae). Histomorphometric analyses of bone sections from these mice show (b) significant inhibition of tumor burden in MDA-231-Gli2-Rep inoculated mice, and (c) decreased immunohistochemical staining for PTHrP in sections from MDA-231-Gli2-Rep mice. The black bar on the histological sections represents a length of 500μM. Values = mean ± standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

Consistent with disrupting TGF-β induced propagation of tumor-induced osteolysis, histomorphometric analyses of the tibiae revealed a significant decrease in tumor burden inGli2-Rep tumor bearing mice relative to empty-vector control tumor-bearing mice (Figure 5b), and this was accompanied by a reduction in detectable PTHrP protein expression identified by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5c).

TGF-β regulation of Gli2 signaling in human osteolytic breast cancer cells

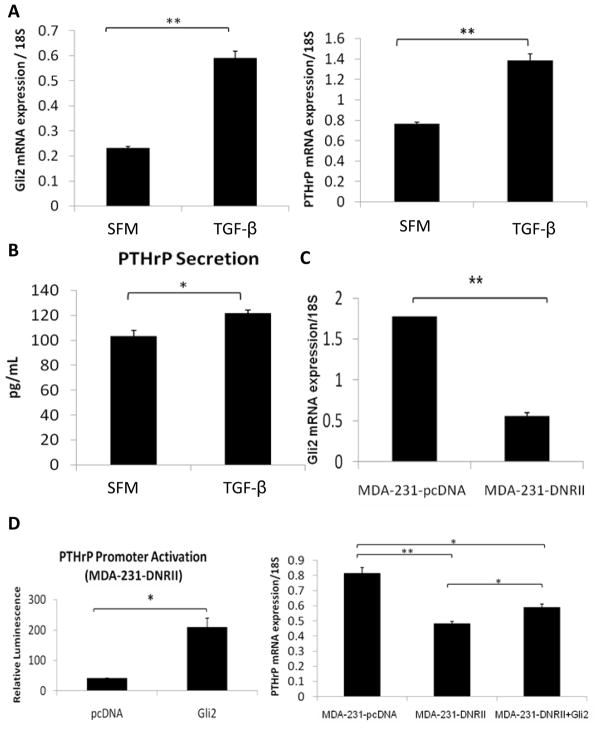

Since TGF-β is known to regulate PTHrP, and other groups have shown that TGF-β regulatesGli2 expression in hepatocarcinoma cells (23), we set out to determine if TGF-β stimulates Gli2 expression in osteolytic tumor cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were tested to determine if TGF-β enhances Gli2 mRNA expression following treatment with 5ng/mL exogenous TGF-β for48 hours. Consistent with previous studies in other cell types, TGF-β significantly enhanced Gli2and PTHrP mRNA expression (Figure 6a) in MDA-MB-231 cells by Q-PCR. As expected, TGF-β also increased PTHrP protein secretion (Figure 6b).

Figure 6. TGF-β regulates Gli2 expression in MDA-MB-231 human osteolytic breast tumor cells.

(a) Gli2 mRNA expression (left panel) increases significantly inMDA-MB-231 cells cultured in serum-free medium (SFM) supplemented with 5ng/mL recombinant TGF-β. As previously published, PTHrP mRNA expression (right panel) increases in MDA-MB-231 cells following 5ng/ml TGF-β treatment. (b) 5ng/ml TGF-β stimulation modestly enhances PTHrP protein secretion in MDA-MB-231 cells. (c) MDA-MB-231 cells stably transfected with the dominant-negative TGF-β receptor type II (DNRII) construct, which abrogates TGF-β signaling, have reduced Gli2 mRNA when compared to empty vector control pcDNA-expressing MDA-MB-231. (d) MDA-231-DNRII cells exhibit low levels of PTHrP promoter activity, but when Gli2 is overexpressed by transfection with a Gli2-expression vector, PTHrP promoter activation is significantly enhanced (left panel) and PTHrP mRNA expression (right panel) is partially restored. Values = mean ± standard error, and p-values were determined using unpaired t-test. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<0.001.

In order to determine if TGF-β signaling is necessary for Gli2 up-regulation in bone metastatic breast cancer cells, we disrupted this signaling pathway through over-expression of a dominant negative TGF-β receptor type II (DNRII) construct in the MDA-MB-231 cells, as previously published (16). When TGF-β signaling was abolished in this way, both Gli2 (Figure 6c) and PTHrP mRNA expression (Figure 6d, right panel) were significantly decreased. These data suggest that Gli2 inhibition impairs the ability of TGF-β to stimulate PTHrP production, resulting in abrogation of tumor-induced bone destruction. Additionally, over-expression of Gli2 protein in the MDA-231-DNRII cells resulted in a dramatic increase in PTHrP promoter activation, and a partial rescue of PTHrP mRNA expression (Figure 6d), further suggesting that Gli2 expression is downstream of TGF-β signaling. The stimulatory effect of TGF-β on PTHrP expression is thus likely to be mediated through Gli2.

Discussion

Our results suggest for the first time that Gli2 inhibition can prevent the formation of breast cancer bone metastases. Many tumor types have mutations that lead to a constitutive activation of Gli proteins, demonstrating a clinical need for identifying targets to inhibit this pathway. Current therapeutic approaches focus primarily on the development of Smo antagonists, such as cyclopamine analogs. However, our data suggest that at least in some cancers, cyclopamine analogs are unlikely to be effective in tumor-induced osteolysis and that direct inhibition of Gli2 activity downstream of Hh receptors has better therapeutic potential for tumor-induced bone disease.

Our studies indicate that several osteolytic tumor cell lines, including human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, either do not express Smo or express it at very low levels, providing an explanation for the observed failure of cyclopamine to inhibit PTHrP expression or tumor-induced bone disease. In light of this data, the expression levels of Hh receptors Smo and Ptc would have been useful prior to in vivo studies. However, it is generally assumed that elevated Gli expression is mediated primarily via upstream Hh receptor activation. Although recently Smo-independent mechanisms have been described in prostate cancer (24), this is the first report with regards to bone metastases of Gli over-expression mediated via a Smo-independent mechanism. Surprisingly, we found that cyclopamine treatment actually increased Gli2 expression, though these results were not significant in some osteolytic tumor cells. While the mechanism of this increase remains unclear, Zhang et al. recently reported that cyclopamine has ‘off-target’ effects on other signaling pathways (25). In addition, other groups have reported that cyclopamine impacts normal bone marrow cell compartments (26–30). Since cyclopamine had no significant effect on overall bone disease in our model, it is unlikely that the compound had any effect on other cells in the bone-tumor microenvironment. However, since duration of treatment in our experiments was relatively short, we cannot rule out that longer-term treatments may alter cells within the bone marrow. These data suggest that Smo antagonists are unlikely to be effective and may even have detrimental effects in some cases of tumor metastasis to bone. It will be necessary to establish how commonly breast and other bone-metastasizing cancers are deficient in Smo expression. These studies are on-going in our laboratory.

Since Smo was not expressed in MDA-MB-231 cells, our alternative approach was to inhibitGli2 activity directly using a Gli2-repressor construct. In this construct, which was previously used to study muscle development in developing organisms, the activation domain of Gli2 has been replaced with the repressor domain of the engrailed protein, resulting in a repression of Gli target genes (21). Inhibiting Gli2 activity in this way reduced PTHrP expression and inhibited tumor-induced bone destruction, which is reflected in the reduction in average osteolytic lesion area as well as number of osteolytic lesions in experiments utilizing populations of MDA cells overexpressing Gli2-Rep derived from single cells (Supplemental Figure 1). To eliminate the possibility that these changes may have been due to constitutive variation in PTHrP expression in individual MDA-MB-231 cells and not due to the inhibition of Gli2 activity, we demonstrated similar results in pooled populations of cells expressing the Gli2-Rep construct (Figures 4&5).

The inhibition of bone destruction and tumor growth observed in the Gli2-Rep tumor bearing mice identifiesGli2 as a promising target for developing therapeutic approaches in the prevention and treatment of tumor-induced bone disease. Postnatal expression of Gli2 is primarily limited to the growth plate (31) and the hair follicle (32, 33), making Gli2 an ideal clinical target with low potential for significant off target effects in adult patients. While there are several reports of potential compounds that inhibit Gli activity (10, 18, 24, 34, 35) only those that inhibit downstream of Smo will be beneficial in cells deficient in Smo, such as those used in this work. One promising group of small molecules is the Gli-Antagonist (GANT) compounds, which inhibit Gli function irrespective of the mutation leading to the activation of Gli (24). However, perhaps due to limited availability as a result of lack of large-scale synthesis of these compounds, they have been tested in relatively few models (24, 36). Importantly, given the frequency of Smo-independent Hh activation in prostate cancer, Smo antagonists are unlikely to be effective in nearly 50% of prostate tumors. The frequency of Hh activation in clinical samples of primary breast cancer (37) and in bone metastases from any primary tumor type is currently unclear, but pre-clinical studies suggest an important role for Hh in tumor-bone disease (9, 38). While ultimately, we and others will need to examine the frequency of Hh mutations in tumors that metastasize to bone in clinical samples.

We observed a decrease in tumor burden at sites of bone metastases in the Gli2-Rep intracardiac model, although tumor growth was unaltered in the Gli2-Rep orthotopic mammary fat pad model. Since canonical Hh signaling did not appear to be regulating Gli2 expression, and recent reports suggested that TGF-β could regulate Gli2 signaling, we reasoned that the observed decrease in tumor growth was caused by indirect blockade of TGF-β stimulation of PTHrP. In this study, we demonstrated that Gli2 is in fact required for TGF-β to increase PTHrP expression. Importantly, this suggests that whenGli2is not activated, TGF-β in the bone matrix will no longer have a stimulatory effect on PTHrP secretion from breast cancer tumor cells and consequently tumor cell growth and bone resorption will be inhibited. While our data indicates that Gli2 is required for TGF-β regulation of PTHrP, this does not exclude other signaling pathways in the regulation of Gli2 and PTHrP. In fact, Dennler et al. recently demonstrated that a combination of Wnt and TGF-β signaling regulates Gli2 transcription (23). Our current efforts are aimed at identifying and characterizing Hh signaling-independent regulators of Gli2 expression in tumor cells that have metastasized to bone.

Overall, this work demonstrates that Gli2 inhibition reduces tumor growth and bone destruction, suggesting that targeting Gli2 may be a valid approach to inhibit bone metastases. Studies are on-going to determine pathways that regulate Gli2 and PTHrP and to test the efficacy of small molecule inhibitors of Hh signaling that target downstream of Hh receptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. T. John Martin for his scientific critiques and help with editing the manuscript, Dr. Daniel Perrien and Mr. Steve Munoz for their assistance with microCT analyses, Mr. Joshua Johnson for assistance with histology, and Mrs. Barbara Rowland for animal assistance. We are grateful to Dr. Ilona Skerjanc from the University of Western Ontario for providing the Gli2-Rep construct.

Funding sources: NIH CA40035-19 (GRM), CA126505-02 (GRM), AR051639 (JAS), NIH F32 (JAS), San Antonio Area Foundation (JAS), NIH CA054174 (SSP), TMENU54 CA126505 (LMM), 5T32CA009592-23 (LMM)

References

- 1.Mundy GR, Edwards JR. PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in hypercalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:672–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007090981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mundy GR, Guise TA. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Am J Med. 1997;103:134–45. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)80047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mundy GR. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. Cancer. 1997;80:1546–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1546::aid-cncr4>3.3.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterling JA, Edwards JR, Martin TJ, Mundy GR. Advances in the biology of bone metastasis: How the skeleton affects tumor behavior. Bone. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.07.015. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guise TA, Yin JJ, Taylor SD, Kumagai Y, Dallas M, Boyce BF, et al. Evidence for a causal role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pathogenesis of human breast cancer-mediated osteolysis. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1544–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI118947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada T, Muguruma H, Yano S, Ikuta K, Ogino H, Kakiuchi S, et al. Intensification therapy with anti-parathyroid hormone-related protein antibody plus zoledronic acid for bone metastases of small cell lung cancer cells in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:119–26. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato K, Onuma E, Yocum RC, Ogata E. Treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia and cachexia with humanized anti-parathyroid hormone-related protein antibody. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:167–73. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito H, Tsunenari T, Onuma E, Sato K, Ogata E, Yamada-Okabe H. Humanized monoclonal antibody against parathyroid hormone-related protein suppresses osteolytic bone metastasis of human breast cancer cells derived from MDA-MB-231. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3817–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton BZ, Peng LF. Small-molecule modulators of the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:44–54. doi: 10.1039/b910196a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauth M, Toftgard R. Non-canonical activation of GLI transcription factors: implications for targeted anti-cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2458–63. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karhadkar SS, Bova GS, Abdallah N, Dhara S, Gardner D, Maitra A, et al. Hedgehog signalling in prostate regeneration, neoplasia and metastasis. Nature. 2004;431:707–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterling JA, Oyajobi BO, Grubbs B, Padalecki SS, Munoz SA, Gupta A, et al. The hedgehog signaling molecule Gli2 induces parathyroid hormone-related peptide expression and osteolysis in metastatic human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7548–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasaki H, Nishizaki Y, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. Regulation of Gli2 andGli3 activities by an amino-terminal repression domain: implication of Gli2 and Gli3 as primary mediators of Shh signaling. Development. 1999;126:3915–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guise TA, Yoneda T, Yates AJ, Mundy GR. The combined effect of tumor-produced parathyroid hormone-related protein and transforming growth factor-alpha enhance hypercalcemia in vivo and bone resorption in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:40–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.1.8325957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallwitz WE, Guise TA, Mundy GR. Guanosine nucleotides inhibit different syndromes of PTHrP excess caused by human cancers in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1559–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI11936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin JJ, Selander K, Chirgwin JM, Dallas M, Grubbs BG, Wieser R, et al. TGF-beta signaling blockade inhibits PTHrP secretion by breast cancer cells and bone metastases development. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:197–206. doi: 10.1172/JCI3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taipale J, Chen JK, Cooper MK, Wang B, Mann RK, Milenkovic L, et al. Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature. 2000;406:1005–9. doi: 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PA. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2743–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez P, Ruiz i Altaba A. In vivo inhibition of endogenous brain tumors through systemic interference of Hedgehog signaling in mice. Mech Dev. 2005;122:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung UI, Lanske B, Lee K, Li E, Kronenberg H. The parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related peptide receptor coordinates endochondral bone development by directly controlling chondrocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13030–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petropoulos H, Gianakopoulos PJ, Ridgeway AG, Skerjanc IS. Disruption of Meox or Gli activity ablates skeletal myogenesis in P19 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23874–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312612200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennler S, Andre J, Alexaki I, Li A, Magnaldo T, ten Dijke P, et al. Induction of sonic hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor-beta: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6981–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennler S, Andre J, Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Cloning of the human GLI2 Promoter: transcriptional activation by transforming growth factor-beta via SMAD3/beta-catenin cooperation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31523–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.059964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lauth M, Bergstrom A, Shimokawa T, Toftgard R. Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Harrington N, Moraes RC, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Lewis MT. Cyclopamine inhibition of human breast cancer cell growth independent of Smoothened (Smo) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:505–21. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao C, Chen A, Jamieson CH, Fereshteh M, Abrahamsson A, Blum J, et al. Hedgehog signalling is essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2009;458:776–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dierks C, Beigi R, Guo GR, Zirlik K, Stegert MR, Manley P, et al. Expansion of Bcr-Abl-positive leukemic stem cells is dependent on Hedgehog pathway activation. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:238–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bar EE, Chaudhry A, Lin A, Fan X, Schreck K, Matsui W, et al. Cyclopamine-mediated hedgehog pathway inhibition depletes stem-like cancer cells in glioblastoma. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2524–33. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peacock CD, Wang Q, Gesell GS, Corcoran-Schwartz IM, Jones E, Kim J, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains a tumor stem cell compartment in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4048–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611682104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trowbridge JJ, Scott MP, Bhatia M. Hedgehog modulates cell cycle regulators in stem cells to control hematopoietic regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604568103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao D, Liu H, Plut P, Niu M, Huo R, Goltzman D, et al. Impaired endochondral bone development and osteopenia in Gli2-deficient mice. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:210–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mill P, Mo R, Fu H, Grachtchouk M, Kim PC, Dlugosz AA, et al. Sonic hedgehog-dependent activation of Gli2 is essential for embryonic hair follicle development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:282–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.1038103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eichberger T, Kaser A, Pixner C, Schmid C, Klingler S, Winklmayr M, et al. GLI2-specific transcriptional activation of the bone morphogenetic protein/activin antagonist follistatin in human epidermal cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12426–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lauth M, Toftgard R. The Hedgehog pathway as a drug target in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8:457–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanton BZ, Peng LF, Maloof N, Nakai K, Wang X, Duffner JL, et al. A small molecule that binds Hedgehog and blocks its signaling in human cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:154–6. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desch P, Asslaber D, Kern D, Schnidar H, Mangelberger D, Alinger B, et al. Inhibition of GLI, but not Smoothened, induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Oncogene. 2010 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visbal AP, Lewis MT. Hedgehog Signaling in the Normal and Neoplastic Mammary Gland. Curr Drug Targets. 2010 doi: 10.2174/138945010792006753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pratap J, Wixted JJ, Gaur T, Zaidi SK, Dobson J, Gokul KD, et al. Runx2 transcriptional activation of Indian Hedgehog and a downstream bone metastatic pathway in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7795–802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.