Abstract

The frequency of peripheral artery aneurysms in the upper extremities is much less than in the lower extremities. Diagnosis and surgical treatment are important, because upper extremity aneurysms can cause severe decreases in function and lead to the loss of an arm or of fingers.

We performed aneurysmal resection together with saphenous vein graft interpositioning in 9 patients with a diagnosis of post-traumatic brachial pseudoaneurysm from January 1995 through February 2003. Of these patients, 7 were men (77%). The mean age was 38.2 years (range, 26–46 years. Four patients had gunshot wounds (44%) and 5 had stab wounds (56%). The mean duration from injury to hospital admission was 26.7 months (range, 17 months–7 years). All patients underwent color-flow arterial Doppler ultrasonography and selective upper extremity digital subtraction angiography.

In all patients, we performed aneurysmal resection and saphenous vein graft interpositioning. There was no instance of death or ischemic extremity loss. Patients were discharged from the hospital a mean of 3.2 days after surgery (range, 2–6 days). Early and late graft patency rates were 100%. We followed the patients' cases for a mean of 3.4 years (range, 1 month–7 years).

Very rarely, post-traumatic upper extremity pseudoaneurysms show symptoms after a long period of time. Diagnosis is very easy with a review of the patient's history and a physical examination; surgical reconstruction is the preferred treatment for such patients. (Tex Heart Inst J 2003;30:293–7)

Key words: Aneurysm, false; brachial artery injuries/surgery; wounds, penetrating/complications

Post-traumatic pseudoaneurysm development is very rare in the peripheral arteries and is generally a late sequela of trauma.

The frequency of peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms is much less in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. 1 Their diagnosis and surgical therapy are very important, because they can cause severe disabilities, including upper extremity and finger loss. Peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms in distal locations, particularly in the brachial artery with localization at the forearm, cause thromboembolic complications in the hands and fingers. 2

When treatment is delayed, hemorrhage, venous edema at the extremity, cutaneous erosion, and, especially, adjacent neurologic structure compression can develop due to enlargement of the pseudoaneurysm. 3 The 1st symptoms of upper extremity aneurysms can be nerve injury or adjacent nerve compression. 4 Care must be taken not to injure the nerves and veins adjacent to a pseudocapsule or scar tissue during surgical procedures. 3

Patients and Methods

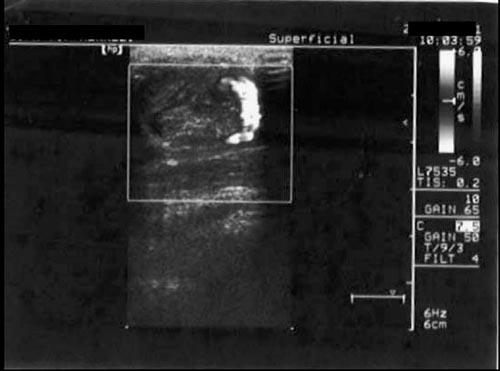

From January 1995 through February 2003, we performed reconstruction with aneurysmal resection and saphenous vein graft interpositioning in 9 patients because of post-traumatic brachial artery pseudoaneurysms. Seven were men (77%) and 2 were women (23%). The mean age was 38.2 years (range, 26–46 years). The patients presented with a pulsating mass at the brachial artery level, which had developed in the late post-traumatic period. We evaluated the upper extremities for ischemia, asked the patient for a medical history, and performed a physical examination, all of which contributed to the diagnosis (Fig. 1). The causes of the pseudoaneurysms were gunshot wounds in 4 patients (44%) and stab wounds in 5 (56%). The mean duration between the date of injury and admission to our clinic was 26.7 months (range, 17 months–7 years). No patient had manifested a vascular problem at the time of injury. Physical examination in all patients showed a mass with systolic souffle in the region of the elbow. Radial and ulnar pulses of the affected upper extremities could be detected manually. Results of the Allen test were negative in all cases. Seven patients (77%) experienced pain and swelling of the forearm, hand, and fingers, especially in winter. Results of routine biochemical, bleeding, and coagulation time tests were within the normal ranges. We performed selective upper extremity arteriography with digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (Fig. 2). In addition, we performed Doppler ultrasonography preoperatively (Fig. 3) and during the late postoperative period (after 3 months). No patient had an arteriovenous fistula. A common result of the postoperative evaluation was arterial flow delay at the hand and wrist level. Preoperative demographic features and previous injuries are shown in Table I. Each patient underwent surgery after the diagnosis of late post-traumatic brachial artery pseudoaneurysm was made.

Fig. 1 View of a brachial artery pseudoaneurysmal mass at the medial right elbow, which appeared 7 years after gunshot injury.

Fig. 2 Right upper extremity angiogram shows brachial pseudoaneurysm after gunshot injury. The half-moon image of contrast material filling an area approximately 2 cm wide on the medial epicondylus of the humerus is consistent with the lesion.

Fig. 3 Doppler ultrasonogram of the patient in Figure 2 shows a pseudoaneurysm at the medial right elbow, 4.5 × 3.5 cm, with an 80% thrombosed lumen. The half-moon opaque segment in the angiogram correlates with the 20%-patent segment of the lumen with turbulent flow.

TABLE I. Demographic Characteristics and Injuries of All 9 Patientsa,b

Surgical Technique

Bupivacaine was used for axillary anesthesia. We performed our standard “S” incision over the pulsating mass to the brachial region. A double layer of skin covering the aneurysm was detached. Exploration was completed by retracting the proximal and then the distal part of the brachial artery with nylon tape (Fig. 4). In the same fashion, the surgical region was controlled by retracting the brachial vein and nerve. After administering 1 cc heparin (5,000 IU) intravenously, we clamped the proximal and distal vascular structures and opened the capsule of the pseudoaneurysm with a direct incision. Organized thrombus in the aneurysm was removed. The capsule was dissected and evaluated histopathologically and microbiologically. In order to avoid increasing the risk of major hemorrhage or nerve injury, we did not resect the aneurysmal pouch completely. We limited the resection by preserving the adjacent tissues. After retrograde flow was restored, a 5- to 6-cm arterial segment that included the pseudoaneurysmal region was resected. Saphenous vein graft interpositioning was then performed, because none of the patients had a vascular structure that was conducive to end-to-end anastomosis. A closed drainage system was placed in the aneurysmal pouch. After hemostasis was achieved, the incision was closed.

Fig. 4 Photograph shows exploration of the pseudoaneurysmal sac during surgery.

Results

There was no instance of death or ischemic extremity loss. Histopathologic evaluation of the pseudoaneurysmal capsules showed that they were all hematomas, with extravasation in the vessel wall lumen, inflammatory infiltration, and hyalinization (Fig. 5). Results of microbiologic examination of the aneurysmal capsule were negative for microorganisms. One patient who was admitted to our clinic 7 years after a gunshot injury had undergone an unsuccessful percutaneous thrombin injection a year before at another institution. In all cases, pulsation was positive upon digital examination at the radial and ulnar arteries during the early postoperative period. No patient required embolectomy in the early or late postoperative period. The late postoperative follow-up examinations were performed at our clinic, and Doppler ultrasonography was performed after 3 months. The early and late graft patency rate was 100%, and we found no other sequelae during the late period. The mean follow-up was 3.4 years (range, 1 month–7 years), and the mean time to discharge was 3.2 days (range, 2–6 days).

Fig. 5 Resected aneurysmal wall material shows lymphocytic inflammatory infiltration and hyalinization (H&E, orig. ×40). There are regions of hematoma with extravasation.

Discussion

Aneurysms can develop in all arteries of the human body. 5 Aneurysms at less common locations are generally due to major trauma, syphilis, Marfan syndrome, or infection. Atherosclerotic aneurysms are often seen in large arteries and in patients of advanced age, but pseudoaneurysms due to penetrating or blunt trauma are seen in patients of every age and at any location. 6,7

Frequency of pseudoaneurysms in the upper extremities is much lower than that in the lower extremities. However, as lifespans increase and diagnostic and evaluation processes improve, the detection of such pseudoaneurysms is becoming more common. 8 Infection, polyarteritis nodosa, congenital arterial defects, and especially trauma play a role in the pathogenesis of upper extremity pseudoaneurysms. Atherosclerotic aneurysm of the brachial artery is very rare. 8 If the only causal factor is trauma, the aneurysm takes the form of a pseudoaneurysm.

Most pseudoaneurysms are the result of penetrating injuries. 6 Minor blunt trauma may cause pseudoaneurysms in patients who are prone to hemorrhage. 9 Sometimes, as in our series, patients are admitted to hospitals with pseudoaneurysms months or years after the trauma. 1,6,10,11

The mean diameter of brachial artery aneurysms in our patients was 4.6 cm (range, 3–8 cm). All patients in our series had a pulsating mass, and 77% had swelling and pain of the forearm, hand, and fingers, especially in winter. Pain and edema develop in the hand and fingers of patients with expanded pseudoaneurysms because of adjacent neurologic structure compression, distal arterial thrombus, and venous edema of the extremity. 3,12 In the series by Cakir and associates, 12 36% of patients had venous edema distal to the pseudoaneurysm. In our patients, hand and finger pain were due to venous edema and adjacent neurologic structure compression. There was no distal arterial embolus in our patients, and Doppler ultrasonography of the hand and finger circulation showed a normal pattern. After aneurysmal resection, pain and paresthesia due to compression were no longer present (at either early or late follow-up). There were no sympathetic neuralgia symptoms. The patients still experienced an increase in pain and swelling in winter. We attributed these symptoms to the effects of the cold on the skin capillaries, because there was no vaso-spastic or obstructive pattern in the distal arteries.

If no neurologic or thromboembolic complications develop, aneurysms of 2 cm or less in diameter can be silent or asymptomatic during a long enlarging period. 13 Such aneurysms can be diagnosed easily by completing a medical history and physical examination. Color-flow Doppler ultrasonography is a noninvasive method that can provide sufficient diagnostic information to plan the surgical procedure.

Upper extremity arterial Doppler ultrasonography and magnetic resonance angiography can be used as diagnostic tools, but the gold standard is selective upper extremity arteriography. 11,14 Doppler ultrasono -graphic evaluation is sufficient for late postoperative follow-up evaluation. 11

Treatments for pseudoaneurysms that can be performed under color-Doppler ultrasonographic guidance are manual compression, ligation, endovascular graft implantation, embolization, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, and surgical reconstruction. 2,6,8,10,12,13 If the procedure is for a lesion in a noncritical distal vessel and does not cause severe ischemia, or if it is clear that the collateral circulation will be sufficient after ligation, then distal and proximal ligation and resection of the pseudoaneurysm can be performed. 15 In addition, these procedures can be performed for pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms that have developed after pancreatitis. 16

A single small aneurysm distal to the brachial bifurcation can be ligated. However, if there is more than 1 aneurysm at the brachial truncus or in the distal region, reconstruction is necessary for the viability of the extremity, as in our patients. 7,10,11

Endovascular graft implantation is a new, minimal ly invasive intervention, and it can be used for aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of the peripheral arterial system and for arteriovenous fistulas. 17 The technique, however, is expensive, and its long-term results are not yet known.

Other methods, such as embolization and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, are not widely used for pseudoaneurysm therapy. Embolization of pseudoaneurysms can be achieved only by embolization of the sac: the pedicle of the sac must be small, and the aneurysm must not disturb the distal circulation to any great extent. Another method—embolization of the artery from the distal and proximal arterial segments—can be used if the collateral circulation is sufficient. 18,19

For many vascular problems, endovascular techniques (or, as in one of our patients, percutaneous thrombin injection, which failed) have been used. Traditional surgery is still considered to yield the best results. 2,11 However, the most convenient method (surgery, obstruction with a percutaneous balloon, em bolization, or a combination stent-graft) must be selected according to the location, size, pathogenesis, and accessibility of the pseudoaneurysm. 11 If the pseudoaneurysm originates from an arterial side branch or an unimportant artery, the arterial entrance and aneurysm can be occluded without excessive concern for the blood supply to the distal tissues. 17,20 Aneurysms situated in larger branches, such as the brachial artery (which is convenient for graft interposition), can be treated by resection of the diseased part and end-to-end anastomosis or with graft interpositioning. 14,15,21 To maintain arterial continuity and to save the extremity, most pseudoaneurysms of the upper extremity, especially of the brachial region, should be treated with reconstruction using saphenous vein interposition. Special care must be taken with regard to brachial artery ligation, which can lead to amputation. 21,22 The amputation rate is more than 50% after brachial artery ligation versus 6% after reconstruction. 22 When pseudoaneurysms are at the brachial bifurcation and proximal to it, saphenous vein graft interpositioning is preferred to maintain arterial continuity and the viability of the extremity. 2,8,11 For these reasons, we used saphenous vein interpositioning for all our patients.

In conclusion, pseudoaneurysm distal to the axillary artery is rare and is frequently the result of a gunshot or stab wound. Axillary and distal peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms of the upper extremity are less dangerous than are thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms. However, thromboembolisms of the extremity can lead to gangrene and amputation; therefore, surgical treatment is important. We recommend not delaying surgical therapy but performing surgical repair routinely for aneurysms and performing revascularization selectively if necessary.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Op. Dr. Ufuk Yetkin, 1379 Sok. No: 9, Burc Apt. D: 13, 35220 Alsancak – Izmir, Turkey

E-mail: ufuk_yetkin@yahoo.fr

References

- 1.Wielenberg A, Borge MA, Demos TC, Lomasney L, Marra G. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery. Orthopedics 2000;23(12):1250,1322–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Nugud OO, Hedges AR. Axillary artery pseudoaneurysm. Int J Clin Pract 2001;55:494–9. [PubMed]

- 3.Robbs JV, Naidoo KS. Nerve compression injuries due to traumatic false aneurysm. Ann Surg 1984;200(1):80–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Ergungor MF, Kars HZ, Yalin R. Median neuralgia caused by brachial pseudoaneurysm. Neurosurgery 1989;24(6):924–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Crawford ES, De Bakey ME, Cooley DA. Surgical considerations of peripheral arterial aneurysms. Arch Surgery 1959;78:226–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, Shah DM, Hollier L, Stanley JC. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on Reporting Standards for Arterial Aneurysms, Ad Hoc Committee on Reporting Standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg 1991;13:452–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Yilmaz AT, Arslan M, Demirkilic U, Ozal E, Kuralay E, Tatar H, Ozturk OY. Missed arterial injuries in military patients. Am J Surg 1997;173(2):110–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Napolitano AM, Napolitano L, Francomano F, Colalongo C, Ucchino S. Aneurysms of the subclavian artery: clinical experience [in Italian]. Ann Ital Chir 1998;69:311–6. [PubMed]

- 9.Kumar S, Agnihotri SK, Khanna SK. Brachial artery pseudoaneurysm following blood donation [letter]. Transfusion 1995;35(9):791. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Haimovici H. Peripheral arterial aneurysms. In: Haimovici H, Ascer E, Hollier LH, Strandness DE Jr, Towne JB, editors. Haimovici's vascular surgery. Cambridge (MA): Blackwell Science; 1996. p. 893–909.

- 11.Tetik O, Yetkin U, Yilik L, Ozsoyler I, Gurbuz A. Right axillary pseudoaneurysm causing permanent neurological damage at right upper limb: A case report. Turk J Vasc Surg 2002;2:102–4.

- 12.Cakir O, Balci AE, Eren S, Ozcelik C, Eren N. Traumatic arteriovenous fistulas. Turk J Vasc Surg 2001;1:28–31.

- 13.Crawford DL, Yuschak JV, McCombs PR. Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery from blunt trauma. J Trauma 1997;42(2):327–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ho PK, Weiland AJ, McClinton MA, Wilgis EF. Aneurysms of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg [Am] 1987;12:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Clark ET, Mass DP, Bassiouny HS, Zarins CK, Gewertz BL. True aneurysmal disease in the hand and upper extremity. Ann Vasc Surg 1991;5:276–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Stabile BE, Wilson SE, Debas HT. Reduced mortality from bleeding pseudocysts and pseudoaneurysms caused by pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1983;118:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Parodi JC, Schonholz C, Ferreira LM, Bergan J. Endovascular stent-graft treatment of traumatic arterial lesions. Ann Vasc Surg 1999;13:121–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mitchell PJ, Tress BM. Management of cerebral aneurysms: current best practice. Med J Aust 1999;171:121–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, Michelini M, Filliung D, Baubly MP, Baker WH. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2000;31(2):289–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Althoff M, Schulte E, Ranft J, Rudofsky G. Occlusion of peripheral aneurysms by arterial stent implantation in inoperable patients—a methodologic alternative [in German]? Vasa Suppl 1992;35:184–5. [PubMed]

- 21.Rudolphi D. An update on the peripheral pseudoaneurysm. J Vasc Nurs 1993;11(3):67–70. [PubMed]

- 22.Rich NM, Baugh JH, Hughes CW. Significance of complications associated with vascular repairs performed in Vietnam. Arch Surg 1970;100(6):646–51. [DOI] [PubMed]