Abstract

The relationship between brain natriuretic peptide and cardiopulmonary bypass has not been examined sufficiently. In this study, we prospectively examined brain natriuretic peptide levels in the plasma of 26 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Brain natriuretic peptide measurements were carried out at 4 times: preoperatively, 3 hours after institution of cross-clamping, 24 hours after institution of cross-clamping, and on the 5th postoperative day. In addition, we measured individual variables and compared them to brain natriuretic peptide levels.

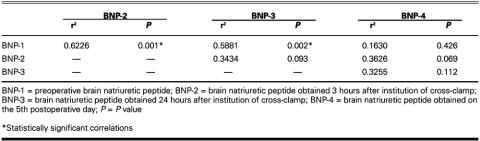

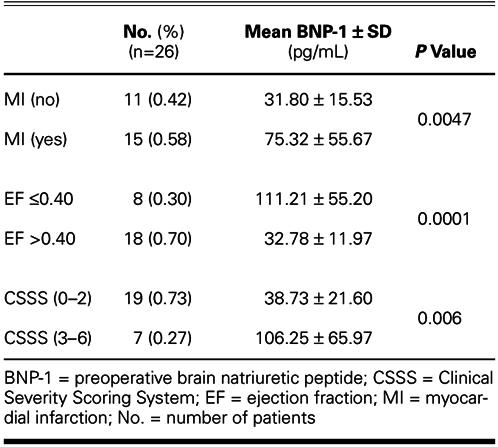

Mean preoperative brain natriuretic peptide levels were significantly higher in patients with histories of myocardial infarction (P = 0.0047) and heart failure (ejection fraction ≤0.40) (P = 0.0001). There was a significant correlation between preoperative brain natriuretic peptide levels and cross-clamp times (P = 0.028), and an inverse correlation between those levels and preoperative cardiac indices (P = 0.001). The preoperative brain natriuretic peptide level also correlated inversely with left ventricular ejection fraction before (P = 0.001) and 5 days after (P = 0.01) operation. When the Clinical Severity Scoring System was applied, preoperative brain natriuretic peptide plasma concentrations in 19 patients with risk scores of 0–2 were significantly lower than in the 7 patients whose risk scores were 3–6 (P = 0.006). There was also a significant relationship between preoperative brain natriuretic peptide plasma concentrations and the postoperative requirement for inotropic agents (P = 0.027).

This study suggests that plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration could be one of the predictors of risk in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. (Tex Heart Inst J 2003;30:298–304)

Key words: Cardiopulmonary bypass; coronary artery bypass; natriuretic peptide, brain; nerve tissue proteins/blood; predictive value of tests; prospective studies

The heart is not only a pump but also an endocrine organ, which synthesizes and secretes 2 different natriuretic peptides: atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Atrial natriuretic peptide is so named because it is derived from the myocytes of the atria, 1–3 and BNP is so named because it originally was isolated from the porcine brain. 4 However, both ventricles of the human heart also secrete BNP. 4–6Both of these cardiac hormones have biologic actions, including natriuresis, diuresis, and vasodilation. 7,8

The plasma concentration of BNP is markedly elevated in patients with congestive heart failure, in proportion to the severity of their disease. 8–10 In addition, many recent studies have revealed that some clinical events, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 11 acute myocardial infarction, 12 dietary sodium loading, 13 exercise, 14,15 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 16 increase the level of plasma BNP. Previous studies 17–21 have reported that changes in plasma ANP concentrations are associated with cardiac surgery, but plasma BNP concentrations have not been established as a prognostic factor for patients who undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Our current prospective study was designed to examine plasma concentrations of BNP during the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods in patients undergoing CABG, and to discover the relationships between plasma BNP levels and various clinical parameters.

Patients and Methods

Twenty-six patients (6 women [23%] and 20 men [77%]; mean age, 58.92 years; range, 42–75 years) who were undergoing CABG surgery were included in the research. Patients who had sustained a myocardial infarction during the past 3 weeks and those who had unstable angina pectoris were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for participation in the study. Only 1 patient was using a β-blocker; no patient was using digitalis. The renal, hepatic, and respiratory functions of all patients were within normal limits. (Previous studies have revealed that abnormal hepatic, renal, and pulmonary functions inversely affect BNP levels. 7,22,23) Neither clinically nor echocardiographically significant cardiac valvular disease was detected in the patients.

The ejection fraction (EF) was greater than 0.40 in 20 patients (77%), as determined by angiography. The remaining 8 (30%) had an EF of 0.40 or lower. Saphenous veins and internal thoracic arteries were used for coronary artery bypass grafts in all cases, and the mean number of grafts was 2.9 per patient. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and the Cleveland Clinic's Clinical Severity Scoring System (CSSS) 24 were used for the evaluation of all patients. Echocardiographic studies were performed preoperatively and on the 5th postoperative day.

Operation. Patients were transported to the operating room in a supine position. All hemodynamic parameters—electrocardiography (ECG), heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), mean pulmonary artery pressure (MPAP), central venous pressure (CVP), cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), systemic vascular resistance (SVR), left ventricular stroke work index (LVSWI), right ventricular stroke work index (RVSWI), left cardiac work (LCW), right cardiac work (RCW), systemic vascular index (SVI), pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP), systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI), left car diac work index (LCWI), and right cardiac work index (RCWI)—were monitored via the radial artery, Swan-Ganz catheters, and a computerized system (Horizon XL, Mennen Medical Corp.; Trevose, Pa). The operative procedure was standard (median sternotomy, aorta–bicaval cannulation, blood cardioplegia warm induction, then cold blood cardioplegia complemented by warm blood “hot shot” hyperkalemic reperfusion, membrane oxygenator, and mild hypothermia) in all cases, and anesthetic management was the same for all patients.

Sampling. Preoperative blood sampling (BNP-1) was carried out from the radial artery cannula while the patient was at rest on the operating table before anesthetic induction. The 2nd samples (BNP-2) were obtained 3 hours after institution of cross-clamping, and the 3rd samples (BNP-3) were obtained 24 hours after institution of cross-clamping while the patients were in the intensive care unit. The final sampling (BNP-4) was carried out from the radial artery on the 5th postoperative day, after the patient had rested for 1 hour in a supine position. Because other studies 14,15 had revealed that BNP plasma levels can rise as a result of exercise, samples were taken while the patients were at bed rest. According to Haug and coworkers, 25 BNP plasma concentrations in the femoral vein are about 10% lower than they are in the left ventricle, so we used the radial artery to obtain samples.

Blood samples were collected into Vacutainer™ tubes, which contain EDTA (disodium ethylene-diaminetetra-acetic acid). Immediately, the tubes were rocked gently several times for the purpose of anticoagulation. Then they were transported to a laboratory in a refrigerated container. The blood samples were transferred into centrifuge tubes containing aprotinin and rocked gently several times to inhibit the activity of proteinases. Then the blood samples were centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 15 minutes at +4 °C (Rotanta 96 R centrifuge; Hettich, Germany), and the plasma was collected. The tubes containing the plasma were sealed with paraffin and stored at −70 °C until the plasma was analyzed for BNP levels.

The brain natriuretic peptide-32 (BNP-32, human) RIA (radioimmunoassay) kit (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Mountain View, Calif) was used in the extraction of peptide from plasma. A Packard Cobra B 5002 gamma counter (Packard Instrument Co.; Meriden, Conn) was used for the analysis of the spec imens. Preparations of specimens for analysis and calculations of results were all carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assay was based upon the competition of 125I-peptide and peptide (either standard or unknown) binding to the limited quantity of antibodies specific for peptide in each reaction mixture. As the quantity of standard or unknown peptide in the reaction increases, the amount of125I-peptide able to bind to the antibody is decreased. The sensitivity of the kit was IC50 20 pg/tube.

Statistical Analysis. Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical results were obtained via SPSS version 4.0. A value of P <0.05 was considered significant. Comparisons of BNP levels between different periods were made by the Wilcoxson matched-pairs signed rank test. Correlations between plasma BNP levels and hemodynamic or clinical or echocardiographic parameters were calculated by the Spearman rank correlation test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to calculate the dif ferences in BNP levels between opposite clinical groups, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the data for multiple groups.

Results

The mean BNP-1 level was 85.08 ± 59.06 pg/mL in women and 48.46 ± 42.42 pg/mL in men. The difference was not significant (P = 0.059). Likewise, there was no relationship between preoperative BNP levels and the age of the patients (r2, 0.0713; P = 0.729). Neither angina classification nor effort classification of patients correlated with preoperative BNP levels (P <0.05). The relationships between BNP-1 levels and patient characteristics are shown in Table I.

TABLE I. BNP-1 Levels and Patient Characteristics

The mean cross-clamp time was 53.42 min (range, 24–114 min). There was a statistically significant correlation between the mean BNP-1 level and the cross-clamp time (r2, 0.4297; P = 0.028), and also between the mean BNP-2 level and the cross-clamp time (r2, 0.4149; P = 0.035).

The relationships between BNP-1 levels and postoperative clinical parameters are shown in Table II. There was a significant relationship between BNP-1 levels and the postoperative requirement for inotropic agents (P = 0.027).

TABLE II. BNP-1 Levels and Postoperative Clinical Parameters

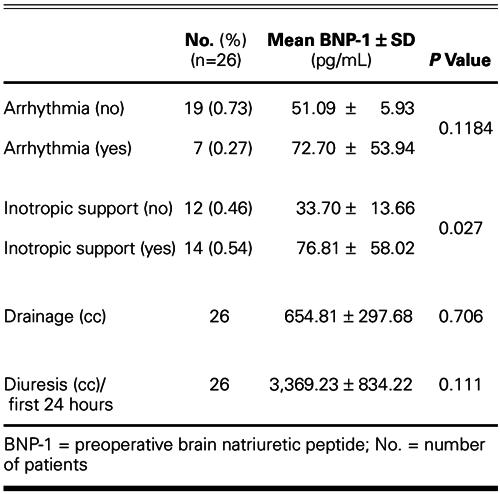

The mean BNP levels in each period were as follows: BNP-1, 56.92 ± 48.10 pg/mL; BNP-2, 90.36 ± 82.94 pg/mL; BNP-3, 144.2 ± 112.43 pg/mL; and BNP-4, 211.32 ± 133.97 pg/mL. The correlations of BNP levels between different periods are shown in Table III.

TABLE III. Correlations of BNP Levels between Different Periods

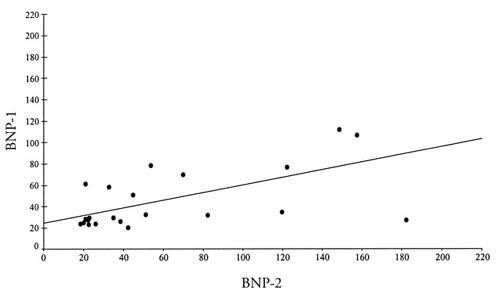

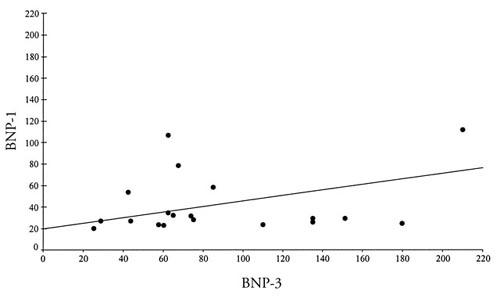

Positive correlations were detected between BNP-1 levels and BNP-2 levels, and also between BNP-1 levels and BNP-3 levels (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Positive correlations between BNP-1 and BNP-2 concentrations.

BNP-1 = preoperative brain natriuretic peptide levels; BNP-2 = brain natriuretic peptide levels 3 hours after institution of cross-clamping

Fig. 2 Positive correlations between BNP-1 and BNP-3 concentrations.

BNP-1 = preoperative brain natriuretic peptide levels; BNP-3 = brain natriuretic peptide levels 24 hours after inst itution of cross-clamping

None of the BNP levels correlated with cardiac enzyme assays that were taken simultaneously (creatine phosphokinase [CPK], isoenzyme of creatine kinase with muscle and brain subunits [CK-MB], and aspartate aminotransferase [AST]). Preoperative and postoperative measurements of cardiac parameters such as HR, MAP, MPAP, PCWP, CI, SVI, SVRI, PVRI, LCWI, LVSWI, RCWI, and RVSWI were all calculated and compared with BNP levels. Among these values, only cardiac index correlated inversely with BNP-1 levels (r2,−0.5919; P <0.05). However, neither BNP-2 levels nor BNP-3 levels correlated with the parameters measured at the same time with their samplings.

Echocardiographic Studies. There was a significant inverse correlation between preoperative left ventricular EF and BNP-1 level (r2, −0.6676; P = 0.001). Likewise, BNP-1 level inversely correlated with left ventricular EF measured on the 5th postoperative day (r2, −0.5365; P = 0.01). In addition, BNP-1 levels correlated with both preoperative left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) and preoperative left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) (r2, 0.6925; P = 0.001; and r2, 0.6005; P = 0.002, respectively). However, BNP-4 levels did not correlate with LVESV and LVEDV. Although there were statistically significant relationships between BNP-1 levels and both LVESV and LVEDV, there was no correlation between BNP-1 levels and left ventricular diameters.

Discussion

Plasma norepinephrine, 26,27 adrenomedulline, 26 renin activity, 10 vasopressin, 28 endothelin-1, 27 tumor necrosis factor-α, 29 atrial natriuretic factor, 1–3,30,31 and recently brain natriuretic factor have all been studied as biochemical markers of cardiac performance. 32,33

Tsutamoto and coworkers reported that BNP levels correlate with age, heart rate, right atrial pressure, PCWP, MPAP, and left ventricular EF. 34 In an echo-cardiographic study, the positive relationship between BNP levels and MPAP in the neonatal period of premature infants was shown. 35 Correlations have been reported between BNP levels and PCWP in congestive heart failure, and also between BNP levels and left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVI) on the 7th day after infarction. 36 In contrast to these reports, we couldn't find any correlation between BNP levels and PCWP, despite having obtained a statistically significant correlation between BNP and left ventricular volumes. Brain natriuretic peptide levels increase as left ventricular volumes increase, as pointed out by previous authors, 37–39 but if the patients who participated in those studies are scrutinized, it is evident that they had either severe valvular disease, like mitral regurgitation, or cardiac failure for various reasons. Therefore, their PCWP values were abnormally high. However, in our patients, the PCWP levels were acceptable, so we could find no correlation between PCWP and BNP. Furthermore, the high sensitivity of BNP to volume changes is demonstrated by the fact that we obtained a statistically significant correlation between BNP and left ventricular volumes despite small volume changes that did not affect the PCWP. We conclude that BNP is both specific and highly sensitive to volume change, even if the change is in small increments. Moreover, there is a correlation between our study and a study by Buhre and co-authors, 40 which reports that changes in cardiac filling pressure do not indicate changes in indices of cardiac volume in patients after coronary bypass surgery.

Changes in BNP levels due to cardiopulmonary bypass have been researched to a lesser extent. Ationu and colleagues 41 studied patients with congenital heart disease, and Mair and associates 42 researched the relationships between BNP levels and cross-clamp effect. Morimoto's group 8 researched perioperative BNP changes in 30 patients who underwent cardiac surgery, but only 7 of those patients had coronary artery bypass grafting. We could not find any study in the English-language literature regarding the preoperative predictive value of BNP in the risk assessment of patients undergoing open heart surgery for coronary artery disease, or comparisons between preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative BNP levels in patients who have undergone CABG. This study was designed to explore these relations.

The patients in this study were examined for operative risks according to Cleveland Clinic's CSSS. The preoperative BNP plasma concentrations among patients with risk scores of 0, 1, or 2 (n=19) were significantly lower than those among patients whose score was 3, 4, 5, or 6 (n=7) (P = 0.006). Thus, the preoperative BNP plasma level could be a significant predictor of the risk of coronary artery bypass surgery.

Although some studies 43 have mentioned a positive correlation between the NYHA classification of patients with chronic mitral stenosis and their plasma BNP concentrations, we could find no correlation between BNP levels and either angina classification or effort classification. Because of our study protocol—which focused on the effect of open heart surgery by excluding patients with additional disease that might lead to volume overload, patients in cardiac failure, and patients with any unstable condition—we did not encounter high levels of BNP in our study. If one compares the BNP levels that we encountered with those reported by Maisel, 39 it is possible to see that the BNP levels among our patients were similar to those among his patients in NYHA class I.

Fifteen of our patients had preoperative myocardial infarction, and their preoperative BNP concentrations correlated with this history. This finding is similar to those of other studies 12,36 and indicates that high BNP concentrations in the presence of preoperative ventricular injury could be an additional indicator of high risk for CABG.

The usual cardiac enzymes did not display statistically significant correlations with BNP levels.

According to the recent literature, troponin has some features that are superior to those of previous markers. As Sabatine and coworkers 44 have pointed out, troponin—together with BNP and CRP (C-reactive protein)—will in future replace the estab lished markers of acute coronary syndrome. We believe that the findings of our present study will also be of help in new investigations.

Many studies 6,32 have suggested that plasma levels of BNP provide a better estimate of left ventricular EF than ANP or adrenomedulline. In our study, we found that patients whose left ventricular EF was 0.40 or less had higher BNP plasma concentrations.

Sayama and coworkers 45 reported that patients with atrial fibrillation had significantly higher levels of ANP and BNP than did patients with sinus rhythm. All of our patients were in sinus rhythm preoperatively. We did not find any relationship between BNP levels and postoperative arrhythmias.

This study also revealed that high preoperative BNP levels significantly correlated with the requirement for postoperative inotropic support. In other words, preoperative plasma BNP concentration could be a predictor of cardiac function in patients who undergo coronary artery bypass surgery.

A significant positive correlation was also found between preoperative BNP levels and aortic cross-clamp times: higher BNP-1 levels and longer cross-clamp times are both associated with more extensive coronary artery disease. We speculate that BNP release rises in response to an increase in myocardial interstitial fluid (edema). As demonstrated by previous studies, 46 interstitial fluid increases in the myocardium during the period of intraoperative cardiac ischemia, despite cardioplegic protection. According to Ferreira and colleagues, 46 both mild mitochondrial edema and mild cytosolic and intermyofibrillar edema were observed in the preischemic samples. In postperfusion samples, that group observed moderate or marked cytosolic and intermyofibrillar edema, together with moderate or severe mitochondrial edema, indicating a higher level of myocardial damage.

In our study, the echocardiographic evaluations demonstrated that BNP-1 levels correlated with preoperative left ventricular volumes (both end-systolic and end-diastolic volume), but not with preoperative left ventricular diameters (end-systolic and end-diastolic diameter). As we mentioned above, this is evi dence of the specificity of BNP to changes in volume, but another conclusion can be inferred: the measurement of ventricular diameters is not as useful a tool for preoperative prediction as is the measurement of ventricular volumes.

In conclusion, this study supports the hypothesis that plasma BNP, secreted mainly by the ventricles, is a biochemical marker of left ventricular dysfunction or damage and points out a further association between markedly elevated plasma BNP concentrations and coronary artery bypass surgery. We tentatively conclude that a high plasma BNP concentration is a predictor of risk in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting, when it is considered in addition to echocardiographic and other known indicators during preoperative evaluation. Therefore, patients with high preoperative plasma BNP concentrations should be managed aggressively and monitored carefully for heart failure after cardiac surgery. New investigations could provide evidence that the routine preoperative measurement of plasma BNP is a useful noninvasive method of assessing risk in coronary artery bypass surgery.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Dr. Osman Saribulbul, 234/1 Sokak No:5, Ersoz B Blok Daire:5, 35040 Bornov a–Izmir, Turkey

E-mail: osaribulbul@yahoo.com

Dr. Coskun is now working in the Dept. of Pediatric Cardiology, Celal Bayar University, Manisa, Turkey.

References

- 1.Anderson JV, Donckier J, McKenna WJ, Bloom SR. The plasma release of atrial natriuretic peptide in man. Clin Sci (Lond) 1986;71(2):151–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Yamada H, Saito Y, Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Yasue H, Ban T, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of atrial natriuretic polypeptide (ANP) in human atrial and ventricular myocardiocytes. Histochemistry 1988;89(5):411–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Berger R, Strecker K, Huelsmann M, Moser P, Frey B, Bojic A, et al. Prognostic power of neurohumoral parameters in chronic heart failure depends on clinical stage and observation period. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003;22(9):1037–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sudoh T, Kangawa K, Minamino N, Matsuo H. A new natriuretic peptide in porcine brain. Nature 1988;332:78–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wei CM, Heublein DM, Perrella MA, Lerman A, Rodeheffer RJ, McGregor CG, et al. Natriuretic peptide system in human heart failure. Circulation 1993;88(3):1004–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Motwani JG, McAlpine H, Kennedy N, Struthers AD. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as an indicator for angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1993;341(8853):1109–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mitaka C, Hirata Y, Nagura T, Tsunoda Y, Itoh M, Amaha K. Increased plasma concentrations of brain natriuretic peptide in patients with acute lung injury. J Crit Care 1997;12(2):66–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Morimoto K, Mori T, Ishiguro S, Matsuda N, Hara Y, Kuroda H. Perioperative changes in plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentrations in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Surg Today 1998;28(1):23–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Hosoda K, Suga S, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, et al. Brain natriuretic peptide as a novel cardiac hormone in humans. Evidence for an exquisite dual natriuretic peptide system, atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide. J Clin Invest 1991;87:1402–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Grantham JA, Borgeson DD, Burnett JC Jr. BNP: pathophysiological and potential therapeutic roles in acute congestive heart failure. Am J Physiol 1997;272(4 Pt 2):R1077–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hasegawa K, Fujiwara H, Doyama K, Miyamae M, Fujiwara T, Suga S, et al. Ventricular expression of brain natriuretic peptide in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1993;88:372–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mukoyama M, Nakao K, Obata K, Jougasaki M, Yoshimura M, Morita E, et al. Augmented secretion of brain natriuretic peptide in acute myocardial infarction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1991;180:431–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lang CC, Coutie WJ, Khong TK, Choy AM, Struthers AD. Dietary sodium loading increases plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels in man. J Hypertens 1991;9:779–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Itoh H, Sagawa N, Nanno H, Mori T, Mukoyama M, Itoh H, Nakao K. Impaired guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate production in severe pregnancy-induced hypertension with high plasma levels of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides. Endocr J 1997;44(3):389–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Steele IC, McDowell G, Moore A, Campbell NP, Shaw C, Buchanan KD, Nicholls DP. Responses of atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure and normal control subjects. Eur J Clin Invest 1997;27(4):270–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lang CC, Contie WJ, Struthers AD, Dhillon DP, Winter JH, Lipworth BJ. Elevated levels of brain natriuretic peptide in acute hypoxaemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992;83:529–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lehot JJ, Piriz H, Carry PY, Gauquelin G, Gharib G, Villard J, et al. Influence of cardiac surgery on atrial natriuretic factor. J Cardiothorac Anesth 1989;3(5 Suppl 1):63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Asari H, Kondo H, Ishihara A, Ando K, Marumo F. Extracorporeal circulation influence on plasma atrial natriuretic peptide concentration in cardiac surgery patients. Chest 1989;96(4):757–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Agnoletti G, Scotti C, Panzali AF, Ceconi C, Curello S, Alfieri O, et al. Plasma levels of atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) and urinary excretion of ANF, arginine vasopressin and catecholamines in children with congenital heart disease: effect of cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1993;7(10):533–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hayashida N, Chihara S, Kashikie H, Tayama E, Yokose S, Akasu K, et al. Biological activity of endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide during cardiopulmonary bypass. Artif Organs 2000;24(10):833–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Roth-Isigkeit A, Dibbelt L, Eichler W, Schumacher J, Schmucker P. Blood levels of atrial natriuretic peptide, endothelin, cortisol and ACTH in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Endocrinol Invest 2001;24(10):777–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Morimoto A, Nishikimi T, Takaki H, Okano Y, Matsuoka H, Takishita S, et al. Effect of exercise on plasma adrenomedullin and naturiuretic peptide levels in myocardial infarction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1997;24(5):315–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Jensen KT, Carstens J, Ivarsen P, Pederson EB. A new, fast and reliable radioimmunassay of brain natriuretic peptide in human plasma. Reference values in healthy subjects and in patients with different diseases. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1997;57(6):529–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Higgins TL, Estafanous FG, Loop FD, Beck GJ, Blum JM, Paranandi L. Stratification of morbidity and mortality outcome by preoperative risk factors in coronary artery bypass patients. A clinical severity score [published erratum appears in JAMA 1992;268(14):1860]. JAMA 1992;267:2344–8. [PubMed]

- 25.Haug C, Metzele A, Kochs M, Hombach V, Grunert A. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide and atrial natriuretic peptide concentrations correlate with left ventricular end-diastolic pressure. Clin Cardiol 1993;16(7):553–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Richards AM, Nicholls MG, Yandle TG, Frampton C, Espiner EA, Turner JG, et al. Plasma N-terminal probrain natriuretic peptide and adrenomedullin: new neurohormonal predictors of left ventricular function and prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998;97(19):1921–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Maeda K, Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Hisanaga T, Kinoshita M. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide as a biochemical marker of high left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in patients with symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Am Heart J 1998;135(5 Pt 1):825–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Francis GS, Benedict C, Johnstone DE, Kirlin PC, Nicklas J, Liang CS, et al. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). Circulation 1990;82:1724–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Nozaki N, Yamaguchi S, Shirakabe M, Nakamura H, Tomoike H. Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors are elevated in relation to severity of congestive heart failure. Jpn Circ J 1997;61(8):657–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lerman A, Gibbons RJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Bailey KR, McKinley LJ, Heublein DM, Burnett JC Jr. Circulating N-terminal atrial natriuretic peptide as a marker for symptomless left-ventricular dysfunction. Lancet 1993;341:1105–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Gottlieb SS, Kukin ML, Ahern D, Packer M. Prognostic importance of atrial natriuretic peptide in patients with chronic heart failure [published erratum appears in J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;14:812]. J Am Coll Cardiol 1989;13:1534–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.McDonagh TA, Robb SD, Murdoch DR, Morton JJ, Ford I, Morrison CE, et al. Biochemical detection of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction. Lancet 1998;351:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kambayashi Y, Nakao K, Mukoyama M, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Shiono S, et al. Isolation and sequence determination of human brain natriuretic peptide in human atrium. FEBS Lett 1990;259(2):341–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Maeda K, Hisanaga T, Maeda Y, Fukai D, et al. Attenuation of compensation of endogenous cardiac natriuretic peptide system in chronic heart failure: prognostic role of plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration in patients with chronic symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 1997;96:509–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ikemoto Y, Nogi S, Teraguchi M, Kojima T, Hirata Y, Kobayashi Y. Early changes in plasma brain and atrial natriuretic peptides in premature infants: correlation with pulmonary arterial pressure. Early Hum Dev 1996;46(1–2):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Nagaya N, Nishikimi T, Goto Y, Miyao Y, Kobayashi Y, Morii I, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide is a biochemical marker for the prediction of progressive ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1998;135:21–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Maki N, Yoshiyama M, Omura T, Yoshimura T, Kawara-bayashi T, Sakamoto K, et al. Effect of diltiazem on cardiac function assessed by echocardiography and neurohumoral factors after reperfused myocardial infarction without congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2001;15(6):493–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nakamura M, Kawata Y, Yoshida H, Arakawa N, Koeda T, Ichikawa T, et al. Relationship between plasma atrial and brain natriuretic peptide concentration and hemodynamic parameters during percutaneous transvenous mitral valvulotomy in patients with mitral stenosis. Am Heart J 1992;124:1283–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Maisel A. BNP—a small peptide promises a big role. Heart Failure Society of America Fifth Annual Meeting. Update on heart failure diagnosis. 2001 September 9–11; Washington, DC.

- 40.Buhre W, Weyland A, Schorn B, Scholz M, Kazmaier S, Hoeft A, Sonntag H. Changes in central venous pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure do not indicate changes in right and left heart volume in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 1999;16(1):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Ationu A, Singer DR, Smith A, Elliott M, Burch M, Carter ND. Studies of cardiopulmonary bypass in children: implications for the regulation of brain natriuretic peptide. Cardiovasc Res 1993;27:1538–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mair P, Mair J, Bleier J, Hormann C, Balogh D, Puschendorf B. Augmented release of brain natriuretic peptide dur ing reperfusion of the human heart after cardioplegic cardiac arrest. Clin Chim Acta 1997;261(1):57–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Curello S, Ceconi C, De Giuli F, Cargnoni A, Alfieri O, Pardini A, et al. Time course of human atrial natriuretic factor release during cardiopulmonary bypass in mitral valve and coronary artery diseased patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1991;5:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Gibson CM, Murphy SA, Rifai N, et al. Multimarker approach to risk stratification in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: simultaneous assessment of troponin I, C-reactive protein, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Circulation 2002;105(15):1760–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Sayama H, Nakamura Y, Saitou N, Doi Y, Matsukura S, Sakurai H, Kinoshita M. Factors that influence the serum of atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide concentrations—is there a specific marker for senile patients [in Japanese]? Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi 1998; 35(11):851–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Ferreira R, Fraga C, Carrasquedo F, Hourquebie H, Grana D, Milei J. Comparison between warm blood and crystalloid cardioplegia during open heart surgery. Int J Cardiol 2003;90(2–3):253–60. [DOI] [PubMed]