Abstract

Abdominal cocoon is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction usually diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy. The cause and pathogenesis of the condition have not been elucidated. It primarily affects adolescent girls living in tropical and subtropical regions. Several earlier cases have been reported in males. We describe an 82-year-old man presenting with small bowel obstruction without history of previous abdominal surgery. He was treated by warfarin following aortic valve replacement. Abdominal cocoon was detected at laparotomy. Excision of membrane and lysis of adhesions led to relief of obstruction. Abdominal cocoon is a rare pathology that may be found in all kinds of populations. It may be a rare form of small bowel obstruction diagnosed during surgery in elderly patients.

Keywords: Intestinal obstruction, Abdominal cocoon, Sclerosing peritonitis, Encapsulating peritonitis, Adults

Introduction

Intestinal obstruction is a common surgical emergency in adults, usually occurring secondary to adhesions, bands, incarcerated hernias, or obstructed tumors. Abdominal cocoon, also known as sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis, is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction, characterized by a complete or partial encasement of the small bowel by a fibrocollagenic cocoon-like sac. The etiology of this condition is not well understood; however, it is a form of chronic irritation and inflammation. A history of previous abdominal surgery or peritonitis, chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, prolonged use of the β-blocker practolol, liver cirrhosis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ovarian tecoma have been suggested as causative factors [1]. It has been reported in patients who underwent ventriculoperitoneal or peritoneovenous shunts, and liver transplantation [2]. These patients usually present with features of recurrent episodes of acute or subacute small bowel obstruction.

In most patients preoperative diagnosis is difficult and usually made at laparotomy. We report a case of an octogenarian man who presented with acute small bowel obstruction caused by abdominal cocoon. To our knowledge, this case is of the oldest patient treated with anticoagulants described with this pathology.

Case Report

An 82-year-old man was admitted to our department with acute small bowel obstruction. He had experienced colicky pain during 4 days in addition to vomiting and constipation. He had no previous history of similar complaints, abdominal trauma, or previous abdominal surgery. He was known to have ischemic heart disease and a history of duodenal ulcer. He underwent aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis 14 years ago, and was treated with anticoagulants (warfarin). He never received β-blockers.

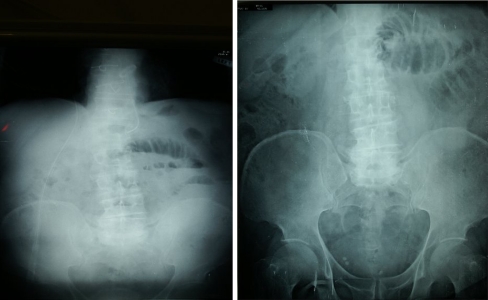

At presentation he was apyrexial and normotensive. Physical examination revealed a mild abdominal distention, mild upper abdomen tenderness, and hyperactive bowel sounds in pitch and frequency. No organomegaly or external hernias were present. Rectal examination was unremarkable. Laboratory blood analyses including complete blood count and biochemistry were within normal limits. INR was increased and consisted with 2.28. An abdominal X-ray showed dilated loops of small bowel with air-fluid levels (Fig. 1). Diagnosis was confirmed by gastrograffin swallow showed stop of the contrast in small bowel loops (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal plan film shows small bowel obstruction

Fig. 2.

Gastrograffin swallow shows stop in jejunum 2 hours later

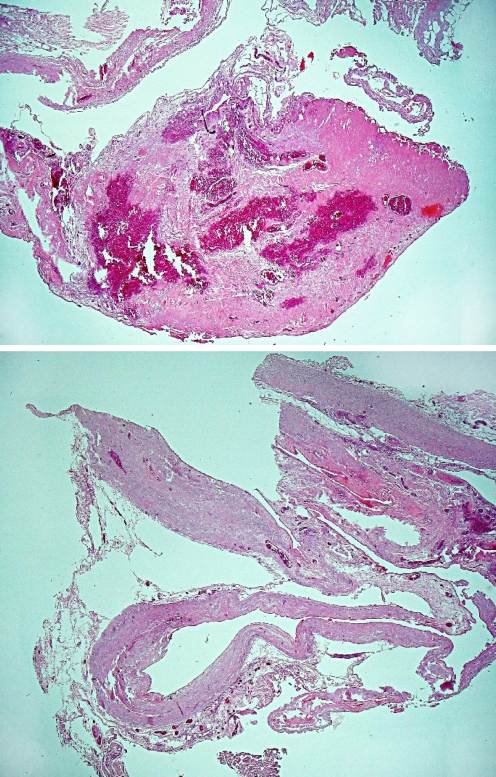

The patient was prepared for surgery. Diagnostic laparoscopy was initially planned. Abdominal palpation revealed a non-tender 10 cm mass in the left abdomen after induction. Laparotomy was determined to be the best approach for this finding. No intra-abdominal fluid was found on exploration. An abdominal cocoon involving the ileum and mid-jejunum was found during surgery. Intestinal loops contained intraluminal fluid and a bezoar-like material possibly contributing to the mechanism of bowel obstruction. Lysis of membrane and adhesions was performed. Histology of the membrane revealed hyalinized fibro-adipose tissue with vascular congestion (Fig. 3). Postoperative course was complicated by rapid atrial fibrillation on day five which was successfully treated by Verapamil (Ikacor) 120 mg daily. He was discharged after 10 days when fully returned to oral anticoagulants.

Fig. 3.

Histology of the membrane revealed hyalinized fibro-adipose tissue with vascular congestion

Discussion

Postoperative adhesions are the most common frequent cause of small bowel obstruction. Despite previous surgery, abdominal cocoon is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction in adults. It characterized by a thick fibrotic membrane that wraps the bowel in a concertina-like fashion. The condition was first observed by Owtschinnikow [3] in 1907 and called “peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata”. The “abdominal cocoon” was first described and so named by Foo et al. [4] in 1978. It is an acquired condition that is often idiopathic. A history of previous abdominal surgery and peritonitis, peritoneovenous or ventriculoperitoneal shunts, chronic abdominal peritoneal dialysis, and liver transplantation have been reported in patients with abdominal cocoon [2]. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis was described in association with treatment by practolol and methotrexate [5], intraperitoneal drug instillation, sarcoidosis, lupus, liver cirrhosis, tuberculosis, endometrial cyst, and ovarian tumors [1]. Geographically, it tends to be confined to the tropical and subtropical regions. It is generally found exclusively in females, although about 10 cases in adult males have been reported in the literature [6–8]. Our case presented an older male Ashkenazi Jewish immigrant from Russia, who had lived in Israel for 15 years. Anticoagulant treatment was not proposed as a cause of abdominal cocoon. We hypothesize that spontaneous intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal bleeding and mild unknown blunt abdominal trauma in patients taking anticoagulants may lead to fibrosis and cocoon formation.

Patients with abdominal cocoon usually present with recurrent episodes of acute or subacute small bowel obstruction, weight loss, nausea, and anorexia, at times with palpable abdominal mass. Most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy performed for obstructive symptoms. However, preoperative diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion. Plain radiographs of the abdomen may suggest features of intestinal obstruction. CT findings of abdominal cocoon include signs of obstruction and clustered small bowel loops encased by a thin soft tissue density mantle [9]. The classic barium meal finding, described by Sieck et al. [10] of a concertina-like or “cauliflower” configuration of dilated small bowel loops, is not always present.

Urgent surgery is indicated for the patient with acute intestinal obstruction without previous abdominal scars. Minimal investigating tools are used preoperatively in such cases. In the virgin abdomen the cause of obstruction should be sought. Laparoscopy is a nice diagnostic tool that may visualize the source of obstruction, which is why the different expensive and time-consuming investigations may be excluded from the preoperative work-up. However, abdominal mass requires conversion in most laparoscopic procedures. This was the basis for the decision for open surgery in our patient.

Surgery remains the cornerstone in the management of abdominal cocoon. The operative procedure of choice is simple membrane dissection and extensive adhesiolysis for release of the entrapped intestine. Resection is indicated only for nonviable bowel and associated with increased morbidity. Surgical complications have been reported including intra-abdominal infection, enterocutaneous fistula, perforated bowel, and partial bowel resections. The long-term prognosis of abdominal cocoon after lysis of adhesions is usually excellent and no recurrence has been described.

Conclusion

Abdominal cocoon is a rare pathology that may be found in all kinds of populations. It may be a rare form of small bowel obstruction diagnosed during surgery in elderly patients. Decortication of membrane and adhesiolysis successfully released the intestinal obstruction.

References

- 1.Kaushik R, Punia R, Mohan H, Attri AK. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon—a report of 6 cases and review of the Literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:18. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maguire D, Srinivasan P, O’Grady J, Rela M, Heaton ND. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 2001;182:151–154. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(01)00685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owtschinnikow PJ. Peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata. Arch Klin Chir. 1907;83:623–634. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427–430. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800650617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdev A, Usatoff V, Thaow C. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis and methotrexate. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46:58–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajagopal AS, Rajagopal R. Conundrum of the cocoon: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1141–1143. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burstein M, Galun E, Ben-Chetrit E. Idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis in a man. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:698–701. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199012000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda C, Fujii Y, Kamiya T, et al. Idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis in a man. Intern Med. 1993;32:552–555. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.32.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hur J, Kim KW, Park MS, Yu JS. Abdominal cocoon: preoperative diagnostic clues from radiologic imaging with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:639–641. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sieck JO, Cowgill R, Larkworthy W. Peritoneal encapsulation and abdominal cocoon. Case reports and a review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:1597–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]