Abstract

Objective of the study was to report the clinical spectrum, investigative profile and management of breast tuberculosis patients attending a tertiary care hospital. Breast tuberculosis is an uncommon form of tuberculosis. Knowledge of its varied clinical presentation and diagnostic modalities help in diagnosing this easily treatable disease. Retrospective data of 63 consecutive patients with breast tuberculosis was analyzed and information regarding demographic details, clinical presentation, cytology, histopathology and management was noted. Breast tuberculosis is essentially a disease of females (98.41%). 49.20% patients were below 30 years of age and 68.25% were from rural areas. Incidence of tubercular mastitis increases with parity (71.42% with p > 2). Commonest presentation was with painless lump (73%). Nodulocaseous tubercular disease was found in 74.60% patients whereas, 6.3% were of disseminated variety. Primary focus was detected in lungs in 11.1% patients, while 46.03% presented with loco-regional lymph nodes. FNAC was found to be a sensitive tool of diagnosis in 74.60% patients; however 25.39% cases were diagnosed with biopsy. ATT remained mainstay of treatment with surgical intervention as and when required. Breast tuberculosis despite being uncommon is not rare. Although diagnosis is not difficult but one should know where to suspect. Once confirmed treatment outcome is often rewarding.

Keywords: Breast tuberculosis, Cytology, Biopsy

Introduction

Tuberculosis is an age old disease. It continues to be a major health hazards along with new diseases like HIV, which resulted in resurgence of extra pulmonary tuberculosis. In 1993, WHO declared tuberculosis to be a global emergency. It is among top ten infectious causes of global mortality with an incidence rate of 150 cases per 100,000 people in 2005 [1]. Currently, one person becomes newly infected every second world wide [2]. Despite high prevalence of tuberculosis, mammary cells offer great resistance to the survival and multiplication of mycobacterium tuberculosis [3]. Sir Astley cooper was the one who reported first case of mammary tuberculosis in 1829 and named it “scrofulous swelling of bosom”, since then there are off and on few cases reported in the literature [4]. The incidence of breast tuberculosis varies from 0.1%–3% of all breast diseases [5]. Significance of breast tuberculosis is due to its rare occurrence and mistaken identity with breast cancer and chronic pyogenic breast abscess. Disease remains elusive for long time but exist without doubt.

Material and Methods

Clinic records of 63 patients attending the breast clinic at Maharana Bhupal hospital attached to Rabindra Nath Tagore Medical College, Udaipur (Rajasthan) between 1992–2008 were analyzed retrospectively. Out of total 5200 cases who attended the clinic, 63 were diagnosed as mammary tuberculosis (Table 1). Apart from routine investigations, all patients of breast lump and nipple discharge underwent ultrasonography and in patients above 35 years of age mammography was also done. Diagnosis of mammary tuberculosis was confirmed by combination of clinical suspicion, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and histopathology findings.

Table 1.

Total cases examined in breast clinic from 1992–2008

| Registered cases | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total cases | 5200 | 100 |

| Breast cancer cases | 924 | 17.76 |

| Routine examination | 541 | 10.40 |

| B.B.D. other than Tb | 3672 | 70.61 |

| Tubercular breast disease | 63* | 1.21 |

*one male patient

Results

Out of 63 patients 62 were females and one was male. It was predominantly a disease of young females with 31 patients below 30 years of age and 14 were lactating. The mean age of patients was 32.28 ± 11.84 years (range16 to75 years). Majority (68.25%) of patients were from rural area and mostly were multiparous (71.42% with p > 2). It was found to be essentially a unilateral disease in majority of patients (96.82%), 42 had involvement of single quadrant and 16 had multiquadrant involvement. Constitutional symptoms were negligible except in patients who had pulmonary tuberculosis (11.1%). Commonest mode of clinical presentation was breast lump, in 46 patients. This was followed by ulcer/sinuses in 13 patients (Fig. 1) and four patients had only nipple discharge (Table 2). Associated loco-regional lymphadenopathy was present in 27 patients.

Fig. 1.

Multiple tubercular ulcer/sinuses with breast lump involving all quadrants of breast

Table 2.

Clinical presentation

| Presentation | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Lump | 46 | 73.01 |

| Ulcer/Sinus | 13 | 20.63 |

| Nipple discharge | 4 | 6.3 |

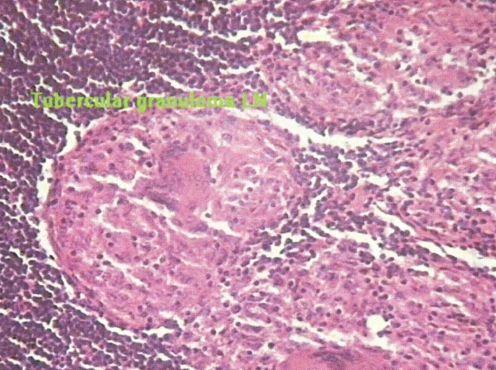

Diagnoses were confirmed by FNAC. Amongst inconclusive FNAC, biopsy supported the final diagnosis of breast tuberculosis. Although FNAC was sensitive in diagnosing tubercular breast cases (47 cases), but 16 cases were diagnosed by biopsy (Fig. 2). Ulcer/sinus cases (9 cases) were subjected only to biopsy. Nipple discharge patients had smear examination, 3 out of 4 had Ziehl Nelsen (ZN) staining +ve for Acid Fast Bacilli (AFB) and PCR (Polymerase chain reaction) for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis was +ve in 2 patients. Chest X-ray of 7 patients showed the findings of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Fig. 2.

Epitheloid granuloma with caseous necrosis and langhans type giant cells (hematoxylin and eosin stained)

All patients were given DOTS Cat-III (2 HRZ + 7 HR) for 9 months. In addition aspiration of abscess was done in 6 patients, excision of lump in 34 patients, drainage of abscess in two patients and one patient was subjected to simple mastectomy for disseminated disease.

Discussion

Despite high prevalence of tuberculosis in developing countries, very few cases of breast tuberculosis have been reported; probably these cases get missed in hype of breast cancer. Breast tuberculosis accounts for up to 3% of surgically treatable breast conditions in India [6, 7]. In our study tubercular mastitis comprised 1.21% of breast diseases and was approximately 14 times less common than breast carcinoma. Mammary tuberculosis is said to be primary if no other focus of tuberculosis exists and secondary in the presence of a demonstrable focus. This primary focus could be in lungs or lymph nodes including axillary, paratracheal and internal mammary lymph nodes [8]. It has been stated that disease is designated as primary erroneously most of the time, when clinicians are unable to detect the underlying focus. Only in rare instances primary breast tuberculosis occurs [9, 10]. Primary forms result from infection of breast tissue through abrasions or through infection of lactiferous ducts in the nipple [11]. Secondary spread could be through hematogenous route, lymphatic route or via spread from contiguous structures. Most widely accepted hypothesis is retrograde lymphatic extension from axillary lymph nodes [12, 13]. Studies report axillary lymph node enlargement in 50%–70% cases of mammary tuberculosis which supports this hypothesis [14]. Axillary lymph nodes were enlarged in 27 of our patients. Although there is no way to demonstrate whether axillary lymph nodes were the site of primary infection or got involved secondary to tubercular mastitis. Further pulmonary tuberculosis as diagnosed on chest X-ray was present in 7 patients thus secondarily infecting the breast tissue. This is in accordance with the study of Afridi et al [15].

Although mammary tuberculosis is much more common in females, it has been also reported in males [7]. In the current article; out of 63 patients one was male. It is seen that lactating females are more susceptible to develop breast tuberculosis. This could be due to increased vascularity of breast during lactation which facilitates infection and dissemination of bacilli. Shinde et al and Banerjee et al reported 7% and 33% of their patients to be lactating at the time of initial presentation [3, 16]. Coincidental tuberculosis of faucial tonsils of suckling infants could be the cause of spread of breast tuberculosis through lacticiferous ducts [4, 17]. In our series 22.2% of the females were lactating when they first presented to us. Breast tuberculosis predominantly affects young multiparous women with most patients between age group 20–40 years [15, 18, 19]. Similar to other studies our 49.2% patients were below 30 years of age. Duration of symptoms as reported by Sharma et al ranged from 6 months–2 years [14]. This is similar to our study with 54 patients having disease duration of 6 months–2 years.

Although there are no structured and acccepted classifications of breast tuberculosis but many authors in their literature have grouped it under three clinical varieties namely nodulocaseous tubercular mastitis, disseminated/ confluent tubercular mastitis and tubercular breast abscess. Nodulocaseous form present as well defined slowly growing painless mass which progressively involves the overlying skin forming sinuses and ulcers. It is this form which is very difficult to differentiate from fibroadenoma in early stage and carcinoma in late stage. This remains the most common variety of breast tuberculosis till date [14, 16, 20]. 47 (74.6%) patients in our series were of nodulocaseous tubercular mastitis. Disseminated breast tuberculosis is characterized by presence of multiple foci throughout the breast tissue which caseates and form sinuses and painful ulcers with overlying skin thickening. Associated axillary lymphadenopathy is mostly present which at times are matted together [16]. In the present study 4 (6.3%) patients were of disseminated tubercular mastitis. Presentation as breast abscess (Fig. 3) was found in 8 (12.6%) patients, suspicion arose when abscesss were recurrent, didn’t heal despite using antibiotics and pus found was sterile in nature. Four patients in our series presented only with nipple discharge (Fig. 4) and could not be classified into any of the above varieties (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Tubercular abscess involving both upper quadrants

Fig. 4.

Seropurulent nipple discharge

Table 3.

New proposed clinical classification

| Type | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Nodulocaseous form | 47 | 74.60 |

| Disseminated form | 4 | 6.3 |

| Tubercular abscess | 8 | 12.6 |

| Nipple discharge | 4 | 6.3 |

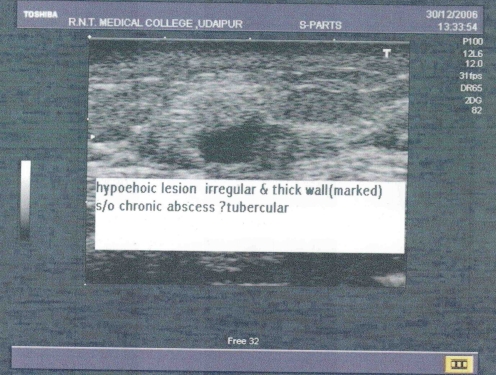

Breast tuberculosis is often misdiagnosed and patients are subjected to extensive investigations before a definite diagnosis is made. Apart from clinical examination FNAC, mantoux test, biopsy, mammography and ultrasonography may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis. FNAC must be done in all cases of breast lump as it usually clinches the diagnosis. Kakkar et al could diagnose breast tuberculosis in 73% of patients and Khanna et al in 100% of their patients on the basis of aspiration cytology [8, 21]. We found FNAC sensitive in 47 patients and rest 16 were diagnosed by biopsy. Mycobacterium culture though the gold standard for diagnosis of tuberculosis requires a lot of time and frequently gives negative results. Nucleic acid amplification test such as PCR is rapid and specific but has low sensitivity [22]. Overall rate of possibility of AFB in Nipple discharge in several studies was 12.00–22.5% [23]. However in our study, 3 out of 4 cases were positive. Chest X-ray should be done in all patients to identify underlying pulmonary tuberculosis. In seven patients of our series pulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed on the basis of chest X-ray (Table 4). Apart from chest X-ray, other radiological investigations like mammography and ultrasonography (Fig. 5) are not very helpful in making the diagnosis, these may however help in defining the extent of lesion but are unreliable in distinguishing tubercular mastitis from carcinoma [11, 24].

Table 4.

Coexisting tuberculosis of other organs

| Organ involved | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Chest | 7 | 11.1 |

| Regional lymph nodes | 29* | 46.03 |

| Genital tuberculosis | 1 | 1.58 |

*axillary lymph nodes:27,supraclavicular lymph nodes:2

Fig. 5.

Ultrasonography showing hypoechoic lesion with irregular and thickened wall

Success rate approaches 95% in most series with 6 months of anti tubercular therapy (2 HRZ + 4HR) [13]. Daali et al recommended ATT for 9 months [18]. All our patients were started on DOTS cat-III (2HRZ + 7HR. In addition excision of lump was done in 34 patients, aspiration of abscess in 6 patients and drainage of abscess in 2 patients (Table 5) Despite ATT, surgical management was required in 45(75.43%) cases. This is well supported by Afridi et al [15].

Table 5.

Treatment

| Treatment | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative Treatment (ATT) | 18 | 28.57 |

| Surgical Treatment | ||

| Aspiration + ATT | 6 | 9.52 |

| Drainage + ATT | 3 | 4.76 |

| Primary excision + ATT | 35 | 55.55 |

| Simple Mastectomy + ATT | 1 | 1.58 |

| Total | 63 | 100 |

Conclusion

Despite one person becoming infected with tuberculosis every second worldwide, tuberculosis of Breast remains uncommon. As the disease has come under better medical control in developed countries, it is becoming a rare entity. However it has shown resurgence with increasing number of HIV cases. Although diagnosis is not difficult but one should know where to suspect. So we thought, it is proper to put an effort and study this interesting, uncommon yet difficult disease of breast.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding nil

Conflict of Interest nil

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopes AD. Global burden of disease. Lancet. 1997;349:1269–1276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet/fs104/en/index.html

- 3.Banerjee SN, Ananthakrishnan N, Mehta RB, Prakash S. Tuberculous Mastitis: a continuing problem. World J Surg. 1987;11:105–109. doi: 10.1007/BF01658471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson TS, Macgregor JW. The diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the breast. Can Med assoc. 1963;89:1118–1124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalali U, Rasul S, Khan A, Baig N, Khan A, Akhter R. Tuberculous mastitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:234–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamit HF, Ragsdale TH. Mammary tuberculosis. J R Soc Med. 1982;75:764. doi: 10.1177/014107688207501002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akcay MN, Saglam L, Polat P, Erdogan F, Albayrak Y, Povoski S. Mammary tuberculosis – importance of recognition and differentiation from that of a breast malignancy. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna R, Prasanna GV, Gupta P, Kumar M, Khanna S, Khanna AK. Mammary tuberculosis: report on 52 cases. Post grad Med J. 2002;78:422–424. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.921.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassilakos P. Tuberculosis of the breast: cytological findings with fineneedle aspiration: a case clinically and radiologically mimicking carcinoma. Acta Cytol. 1973;17:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sen M, Gorpeligoglu C, Bozer M. Isolated primary breast tuberculosis- report of three cases and review of literature. Clinics. 2009;64:607–610. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000600019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: diagnosis, clinical features and management. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domingo C, Ruiz J, Roig J, Texido A, Aguilar X, Morera J. Tuberculosis of the breast: a rare modern disease. Tubercle. 1990;71:221–223. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(90)90081-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baharoon S (2008) Tuberculosis of the breast. Ann Thorac Med 3:110–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sharma PK, Babel AL, Yadav SS. Tuberculosis of breast (study of 7 cases) J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afridi SP, Memon A, Rehman SU. Spectrum of breast tuberculosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:158–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinde SR, Chandawarkar RY, Deshmukh SP. Tuberculosis of the breast masquerading as carcinoma. World J Surg. 1995;19:379–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00299163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Gupta AS, Duggal N. Tubercular mastitis. Int Surg. 1982;67:422–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kedar GP, Bophate SK, Kherdekar M. Tuberculosis of breast. Ind J Tub. 1985;32:146. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsiddig KE, Khalil EA, Elhag IA, Elsafi ME, Suleiman GM, Elkhidir IM, et al. Granulomatous mammary disease: ten years experience with fine needle aspiration cytology. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Popli MB. Pictorial essay: tuberculosis of the breast. Indian J Radiol Imag. 1999;9:127–312. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakkar S, Kapila K, Singh MK, Verma K. Tuberculosis of the breast: a cytomorphological study. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:292–296. doi: 10.1159/000328467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sriram KB, Moffatt D, Stapledon R. Tuberculosis infection of the breast mistaken for granulomatous mastitis. Cases J. 2008;1:273. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mirsaeidi SM, Masjedi MR, Mansouri SD, Velayati AA. Tuberculosis of the breast: report of four clinical cases and literature review. Health J. 2007;13:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zandrino F, Monetti F, Candolfo N. Primary tuberculosis of breast. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:61–63. doi: 10.1080/028418500127344768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]