Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the nutritional advantages of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) in comparison with distal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis (DG) in early gastric cancer (EGC). Between 2005 and 2007, 24 patients underwent PPG and 30 underwent DG. Subjective global assessment, objective data assessment, and endoscopic findings of the remnant stomach were compared between the two groups. Two years after surgery, the patients’ body weights recovered to 97% in PPG, but they continued to decrease in DG. Postoperative blood lymphocyte counts remained low in DG, but recovered to preoperative levels 6 months after surgery in PPG. Food residue in the gastric remnant was frequently observed in PPG (71.4%) than in DG (15.8%, P = 0.001). In nutritional aspect, PPG may be a more ideal operation than DG. However, food residue in the gastric remnant should be considered in PPG.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12262-010-0167-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Gastrectomy, Gastric cancer, Pylorus, Surgical procedures, Treatment outcome

Introduction

Distal gastrectomy is the most common surgical method for gastric cancer. However, this procedure often leads to nutritional disadvantages, such as weight loss [1]. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy (PPG) was originally used as a surgery for gastric ulcer patients to prevent dumping syndrome and duodenal juice reflux [2]. Recently, this surgical technique has been performed in patients with early gastric cancer located in the middle third of the stomach as one of the limited number of operations for gastric cancer [3]. Thus, now we have two surgical methods for patients diagnosed with early gastric cancer in the middle third of the stomach: conventional distal gastrectomy (DG) and PPG. However, the nutritional assessment of patients who have undergone gastrectomy has not been well studied.

In the present study, in order to determine whether there is a nutritional advantage of the PPG method, we retrospectively evaluated and compared postoperative subjective and objective nutritional assessments between two patients’ groups, those who underwent DG and those who underwent PPG.

Methods

Patients

The indications for PPG include the following criteria: (1) a diagnosis of early gastric cancer, (2) tumor located in the middle third of the stomach, (3) no lymph node metastasis, and (4) tumor less than 5.0 cm in diameter. Between January 2005 and December 2007, 24 patients were diagnosed preoperatively by computed tomography as having early gastric cancer in the middle third of the stomach without lymph node metastasis. These patients underwent PPG. Also, in the same period, 30 patients were diagnosed with early gastric cancer in the lower third or lower to middle third of the stomach without lymph node metastasis, and underwent DG with Billroth I anastomosis. A total of 54 patients were enrolled in this study. The preoperative diagnosis of gastric cancer was established by endoscopic and histopathological examinations. The depth of invasion was evaluated by endosonography. All patients were followed until October 2009 at our hospital.

Surgical Procedure

In conventional DG, D1 or D2 lymphadenectomy has been performed. In order to conserve pyloric function and to retain the blood flow to the remnant antral segment, the pyloric and hepatic branches of the vagus nerve and the right gastric artery were preserved in PPG. As a result, the No. 5 and 12 lymph nodes were not dissected in the PPG group. When PPG was performed, a 3-cm length of antral segment was preserved and the proximal stomach was divided at a point approximately 3 cm distant from the primary tumor. End-to-end anastomosis was performed using the Gambee suture technique.

Clinicopathological Findings

The histopathological findings, stage classification, depth of tumor invasion, lymph node grouping, and curability of gastric resection were reported according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma [4].

Patients’ Postoperative Nutritional Assessment

The subjective global assessment (SGA) [5] and laboratory blood data were completed every 6 months postoperatively for 24 months in every patient, as the patients’ subjective and objective nutritional assessments, respectively. Subjective findings, such as food intake, regurgitation, stasis, and postprandial dumping syndrome were scored according to the level of disturbance, 0: no disturbance, 1: slight disturbance, 2: mild disturbance and 3: severe disturbance. Scores 0 and 1 were classified as the ‘not disturbed’ group and scores 2 and 3 were classified as the ‘disturbed’ group. Also, objective findings such as postoperative body weight, serum albumin, serum total cholesterol, and blood lymphocyte count were compared with those of preoperative levels.

Endoscopic Evaluation

A total of 33 patients (DG: 19 and PPG: 14) received gastrointestinal endoscopy at 24 months after gastrectomy. The Los Angeles Classification was used to diagnose and describe erosive esophagitis [6]. The degree of residual gastritis and the amount of food residue in the gastric remnant were classified according to a previous report [7].

Statistical Analysis

The Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact probability tests were used to compare the distribution of individual variables between the patient groups. Differences in the data between the two groups were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients. Patient age in the PPG group was younger (mean 61 years) than in the DG group (mean 68 years). The percentage with submucosal cancer in the DG group was much higher than in the PPG group. However, the length of postoperative hospital stay and the tumor stages were not different between the two groups. No patient died after surgery. Postoperative complications were detected in 3 of 30 in the DG group (anastomotic stenosis: 2 and stasis: 1), and in 1 of 24 in the PPG group (stasis: 1). Occurrence of complications after DG was not different from that after PPG (P = 0.416).

Table 1.

Back ground of the patients

| DG | PPG | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 30 | 24 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 68 ± 13 | 61 ± 12 | 0.022 |

| Sex (male/female) | 18/12 | 13/11 | 0.667 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days, mean + SD) | 15.1 ± 7.8 | 13.5 ± 6.4 | 0.446 |

| Depth of tumor invasion | |||

| m | 0 | 13 | <0.001 |

| sm | 30 | 10 | |

| mp | 0 | 0 | |

| ss | 0 | 1 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| No | 29 | 23 | 0.895 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | |

| Stage | |||

| IA | 28 | 22 | 0.816 |

| IB | 2 | 2 | |

SD: standard deviarion

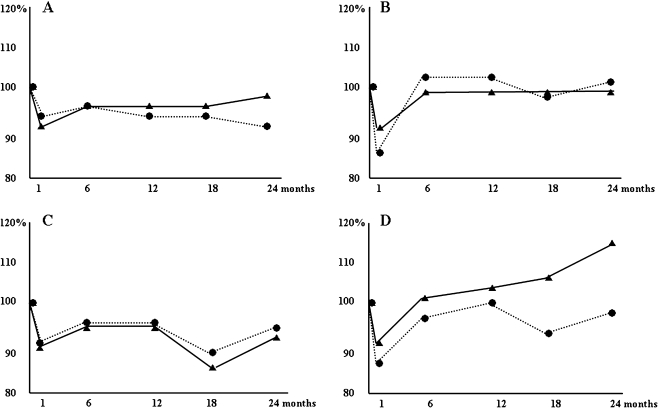

Subjective findings 24 months after surgery are indicated in Table 2. Even though no significant differences were found, food intake disturbance and postprandial dumping syndrome were frequently found in the DG group. Patients’ body weights in the DG group continued to decrease even after 24 months postoperatively. On the other hand, in the PPG group, patients’ body weights recovered to 97% of their preoperative weight at 24 months after surgery (Fig. 1a). But, the difference was not significant (P = 0.377). Postoperative levels of serum albumin and serum total cholesterol of patients in the PPG group were almost the same as those in the DG group (Fig. 1b, c). However, when we compared the patients’ postoperative blood lymphocyte counts with preoperative levels, we found that the levels were still at preoperative levels in the DG group even 24 months after surgery, (1 month; 86%, 6 months; 97%, 12 months; 99%, 18 months; 93%, and 24 months; 98%). In contrast, the PPG patients’ blood lymphocyte counts recovered to the preoperative levels after 6 months, and the level continued to increase gradually (1 month; 88%, 6 months; 101%, 12 months; 103%, 18 months; 106%, and 24 months; 115%). However, the difference between the groups was not significant 24 months after surgery (P = 0.149, Fig. 1d).

Table 2.

Subjective findings after 2 years from the operation

| No disturbed | Disturbed | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food intake | DG | 24 | 6 (20) | 0.231 |

| PPG | 22 | 2 (8.3) | ||

| Regurgitation | DG | 29 | 1 (3.3) | 0.367 |

| PPG | 24 | 0 | ||

| Stasis | DG | 27 | 3 (10) | 0.416 |

| PPG | 23 | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Postprandial dumping syndrome | DG | 27 | 3 (10) | 0.111 |

| PPG | 24 | 0 | ||

Fig. 1.

Objective data of 24 patients in the pylorus-preserving gastrectomy group (solid line) and of 30 patients in the distal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis group (dotted line) a: body weight; b: serum albumin; c: serum total cholesterol; d: blood lymphocyte count

We investigated the postoperative condition of the esophagus and the residual stomach in 33 cases by endoscopy. Slight to moderate esophagitis was detected in five of 19 patients in the DG group (26.3%) and in five of 14 (35.7%) patients in the PPG group. Gastritis was detected in 11 of 19 (57.9%) DG patients and in six of 14 (42.9%) PPG patients. The incidence of postoperative esophagitis or gastritis after DG was found to be similar to that after PPG (esophagitis: P = 0.562 and gastritis: P = 0.913). Duodenogastric bile reflux was detected in 11 DG patients with postoperative gastritis, but it was not detected in PPG. On the other hand, food residue in the gastric remnant was more frequently observed in the PPG group (71.4%) than in the DG group (15.8%, P = 0.001, Table 3). And, esophagitis and gastritis after PPG was detected in such cases with food residue in the gastric remnant.

Table 3.

Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus and residual stomach at 2 years after the gastrectomy

| DG | PPG | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 19 | 14 |

| Esophagitis | ||

| No esophagitis | 14 | 9 |

| Grade A | 3 | 4 |

| B | 0 | 1 |

| C | 2 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 0 |

| Degree of gastritis | ||

| Grade 0 | 8 | 8 |

| 1 | 6 | 1 |

| 2 | 5 | 3 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Residual food | ||

| No residual food | 16 | 4 |

| Small amount of residual food | 1 | 2 |

| Moderate to grate amount of residual food | 2 | 8 |

The correlation between endoscopic findings (food residue in the gastric remnant) and subjective findings (food intake disturbance, regurgitation, and stasis) was analyzed. One of 13 patients with food residue in the gastric remnant (7.7%) complained of stasis, also one of 20 patients without food residue in the gastric remnant (5%) complained of food intake disturbance. The difference was not significant (P = 0.752).

Discussion

Many previous reports have focused on the functional aspects of PPG compared with the traditional DG. Dumping symptoms were reported in 4–46% of DG patients, but only in 0–13% of PPG patients [8–10]. Hotta et al. [11] reported that nutritional status and serum albumin and hemoglobin levels were better in PPG than in DG patients. Park et al. [12] reported that gastritis, bile reflux, and gallbladder stones were not observed in PPG patients and were observed only in DG patients. These results strongly suggested that patients with early gastric cancer who underwent PPG appeared to have many advantages in quality of life (gastrointestinal symptoms, nutritional status, and gallbladder stone incidence) compared to those who underwent DG. Also, PPG could prevent progressive body weight loss after gastrectomy unlike DG. Unfortunately, we could not find obvious nutritional benefits of PPG compared with DG in the present study. Postoperative serum albumin and serum total cholesterol levels in the PPG group were similar to those of the DG group.

It is well known that circulating lymphocytes play an important immunological role in various carcinomas [13, 14]. In gastric cancer, peripheral lymphocyte subsets were reported to be suppressed to different degrees [15]. Also, Gwak et al. [16] demonstrated that the peripheral neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio might indicate individual immunity after gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. After gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer, the peripheral lymphocyte count was suppressed in many patients [17]. In the present study, we found that the number of peripheral lymphocytes was suppressed for a long time in patients who underwent DG even in early gastric cancer. In contrast, in patients who underwent PPG, the number of peripheral lymphocyte recovered within 1 month after operation to the preoperative level. Also, the number of peripheral lymphocytes continuously increased during the 2 years after surgery in the PPG group. This finding may suggest an immunological benefit after PPG for patients with early gastric cancer.

In PPG, to retain pyloric function, the pyloric branch of the vagal nerve was preserved. However, our present data and other previous studies demonstrated, with postoperative endoscopy, a large amount of residual food in the gastric remnant in PPG patients [18, 19]. Nishikawa et al. [20] demonstrated by scintigraphy that gastric emptying was delayed in PPG patients compared to DG patients after vagal pyloric branch preservation. These results indicated that to keep pyloric function normal, vagal pyloric branch preservation may not be enough. Residual food in the remnant stomach may disturb the endoscopic follow-up of patients after PPG. Thus, we may overlook secondary cancer developing in the remnant stomach because of the presence of residual food [21]. Even, we found no duodenogastric bile reflux in PPG patients, we found the esophagitis or gastritis in 30 ∼ 40% of PPG patients, and such patients had residual food in their remnant stomach. Thus, this residual food in the remnant stomach may cause the esophagitis or gastritis in PPG patients.

Recently, it has been reported that preservation of the celiac branch of the vagal nerve at gastrectomy improved postoperative gastrointestinal movement including that in the residual stomach [22]. Thus, in the future, we need to investigate the functional benefit of preservation of the celiac branch of the vagal nerve in patients who are selected for PPG.

Even though, this was retrospective study, this study indicated that PPG should be a more ideal operation than DG, in nutritional or immunological aspects, for patients with early gastric cancer located in the middle third of the stomach. Future larger studies are warranted to investigate this further. In addition, food residue in the gastric remnant should be taken into account after PPG when investigating the presence of secondary cancer in the stomach.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 27 kb)

References

- 1.Katsube T, Konnno S, Murayama M, Kuhara K, Sagawa M, Yoshimatsu K, Shiozawa S, Shimakawa T, Naritaka Y, Ogawa K. Changes of nutritional status after distal gastrectomy in patients with gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1864–1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maki T, Shiratori T, Hatafuku T, Sugawara K. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomy as an improved operation for gastric ulcer. Surgery. 1967;61:838–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morita S, Katai H, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Sasako M. Outcome of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1131–1135. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 2nd English ed. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/PL00011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baccaro F, Moreno JB, Borlenghi C, Aquino L, Armesto G, Plaza G, Zapata S. Subjective global assessment in the clinical setting. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007;31:406–409. doi: 10.1177/0148607107031005406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubo M, Sasako M, Gotoda T, Ono H, Fujishiro M, Saito D, Sano T, Katai H. Endoscopic evaluation of the remnant stomach after gastrectomy: proposal for a new classification. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s101200200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D, Shimoyama S, Kaminishi M. Feasibility of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy with a wider scope of lymphadenectomy. Arch Surg. 1998;133:993–997. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakane Y, Akehira K, Inoue K, Iiyama H, Sato M, Masuya Y, Okumura S, Yamamichi K, Hioki K. Postoperative evaluation of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:590–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata C, Shiiba KI, Funayama Y, Ishii S, Fukushima K, Mizoi T, Koyama K, Miura K, Matsuno S, Naito H, Kato E, Honda T, Momono S, Ouchi A, Ashino Y, Takahashi Y, Fujiya T, Iwatsuki A, Sasaki I. Outcomes after pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: a prospective multicenter trial. World J Surg. 2004;28:857–861. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hotta T, Taniguchi K, Kobayashi Y, Johata K, Sahara M, Naka T, Terashita S, Yokoyama S, Matsuyama K. Postoperative evaluation of pylorus-preserving procedures compared with conventional distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Today. 2001;31:774–779. doi: 10.1007/s005950170046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park DJ, Lee H-J, Jung HC, Kim WH, Lee KU, Yang H-K. Clinical outcome of pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in gastric cancer in comparison with conventional distal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis. World J Surg. 2008;32:1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9441-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milasiene V, Stratilatovas E, Norkiene V, Jonusauskaite R. Lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood as prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. J BUON. 2005;10:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogar P, Sperti C, Basso D, Sanzari MC, Greco E, Davoli C, Navaglia F, Zambon CF, Pasquali C, Venza E, Pedrazzoli S, Plebani M. Decreased total lymphocyte counts in pancreatic cancer: an index of adverse outcome. Pancreas. 2006;32:22–28. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000188305.90290.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong WS, Hong SI, Kim CM, Kang YK, Song JK, Lee MS, Lee JO, Kang TW. Differential depression of lymphocyte subsets according to stage in stomach cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1991;21:87–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jjco.a039451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwak MS, Choi SJ, Kim JA, Ko JS, Kim TH, Lee SM, Park JA, Kim MH. Effects of gender on white blood cell populations and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio following gastrectomy in patients with stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(Suppl):S104–S108. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung IK, Kim MC, Kim KH, Kwak JY, Jung GJ, Kim HH. Cellular and peritoneal immune response after radical laparoscopy-assisted and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:54–59. doi: 10.1002/jso.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imada T, Rino Y, Takahashi M, Hatori S, Tanaka J, Shiozawa M, Chin C, Yamamoto Y, Amano T, Nakamura K. Gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving gastrectomy in comparison with conventional subtotal gastrectomy for early gastric carcinoma. Surg Today. 1998;28:135–138. doi: 10.1007/s005950050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunobu S, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sano T. Symptom evaluation of long-term postoperative outcomes after pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:167–172. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishikawa K, Kawahara H, Yumiba T, Nishida T, Inoue Y, Ito T, Matsuda H. Functional characteristics of the pylorus in patients undergoing pylorus-preserving gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surgery. 2002;131:613–624. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagano H, Ohyama S, Sakamoto Y, Ohta K, Yamaguchi T, Muto T, Yamaguchi A. The endoscopic evaluation of gastric remnant residue, and the incidence of secondary cancer after pylorus-preserving and transverse gastrectomies. Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:54–59. doi: 10.1007/s10120-004-0269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsujii H, Andoh S, Sakakibara K. The clinical evaluation of vagus nerve preserving gastric operation with D2 lymph node dissection for early and advanced gastric cancer (in Japanese) Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2003;36:78–84. doi: 10.5833/jjgs.36.78. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 27 kb)