Abstract

The peptidoglycan (PGN)-recognition protein LF (PGRP-LF) is a specific negative regulator of the immune deficiency (Imd) pathway in Drosophila. We determine the crystal structure of the two PGRP domains constituting the ectodomain of PGRP-LF at 1.72 and 1.94 Å resolution. The structures show that the LFz and LFw domains do not have a PGN-docking groove that is found in other PGRP domains, and they cannot directly interact with PGN, as confirmed by biochemical-binding assays. By using surface plasmon resonance analysis, we show that the PGRP-LF ectodomain interacts with the PGRP-LCx ectodomain in the absence and presence of tracheal cytotoxin. Our results suggest a mechanism for downregulation of the Imd pathway on the basis of the competition between PRGP-LCa and PGRP-LF to bind to PGRP-LCx.

Keywords: Drosophila , innate immunity, structural biology

Introduction

Antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production by immune competent cells is an essential part of the insect immune response. By using Drosophila genetics, it has been possible to progressively decipher the signalling cascades that mediate AMP production upon microbial infection (Ferrandon et al, 2007). It is now established that two nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-dependent signalling cascades control the regulation of most of the immune-induced genes in Drosophila. The Toll pathway is mainly activated by Gram-positive bacteria during the systemic immune response (Lemaitre et al, 1996). Detection of Lys-type peptidoglycan (PGN)—which is present in most of the Gram-positive bacteria cell walls—by the circulating pattern-recognition receptor PGRP-SA, ultimately leads to Spätzle maturation and Toll activation (Michel et al, 2001). Gram-negative bacteria and their diaminopimelic acid (DAP)-type PGNs trigger another NF-κB-dependent cascade—the immune deficiency (Imd) pathway—through the transmembrane receptor known as PGN-recognition protein LC (PGRP-LC; Choe et al, 2002, 2005; Gottar et al, 2002; Ramet et al, 2002; Leulier et al, 2003). Alternative splicing at the PGRP-LC loci results in three receptor isoforms, in which different PGRP domains—LCa, LCx and Lcy—are fused to a common invariant cytoplasmic domain. For reasons that remain unclear, it seems that the Drosophila immune system uses different PGRP receptor combinations to detect monomeric and polymeric PGN. Biochemical experiments have shown that LCa alone does not have affinity to polymeric PGN or to its monomeric derived muropeptides, tracheal cytotoxin (TCT). However, it has been shown that PGRP-LCa is important in the DAP-type PGN receptor complex. The current model is that TCT binds to and is presented by the LCx ectodomain for recognition by the LCa ectodomain (Mellroth et al, 2005; Chang et al, 2006). The PGRP-LCx isoform recognizes polymeric PGN, and it has been proposed that PGRP-LCx forms clusters on this polymeric ligand.

Activation of the immune response is energetically expensive, and inappropriate activation is detrimental to the host. Consistent with this idea, overactivation of the Imd pathway in wild-type flies is lethal. To keep the immune response properly modulated, the activation of the Imd pathway is tightly regulated at many levels. This includes the control of availability of the ligand by amidases (Bischoff et al, 2006; Zaidman-Remy et al, 2006), the control of membrane localization of the PGRP-LC receptor by the Pims protein (Lhocine et al, 2008) and the control of occupancy of the NF-kB-binding site on immune-induced promoter genes by the Caudal transcription factor (Ryu et al, 2008). Two recent studies have shown that the transmembrane protein PGRP-LF, also acts as a specific negative regulator of the Imd pathway (Persson et al, 2007; Maillet et al, 2008). PGRP-LF contains a 23-amino-acid intracellular tail, a transmembrane domain and two extracellular PGRP motifs (LFw and LFz) that have strong sequence similarity to the PGRP domains of PGRP-LCa and -LCx. Reduction in PGRP-LF levels in vivo, in the absence of infection, is sufficient to trigger Imd pathway activation. Consistent with this finding, overexpression of PGRP-LF in flies blocks the induction of AMP synthesis after microbial challenge. Two models have been proposed to account for these immune phenotypes. The first model proposes that by interacting with PGRP-LC, PGRP-LF prevents spontaneous PGRP-LC dimerization and therefore avoids spontaneous Imd pathway activation. The alternative hypothesis is that PGRP-LF binds to PGN and by doing so reduces or titrates out the endogenous stimulatory PGN. The latter model is supported by Persson et al (2007), who have reported that a tagged recombinant PGRP-LF is able to bind to insoluble PGN.

To discriminate between these hypotheses and to understand the structural basis of the unique role of PGRP-LF in negatively regulating the Imd pathway, we determined the crystal structure of the two PGRP domains that form the ectodomain of PGRP-LF.

Results

Overall structure of LFz and LFw domain

Drosophila PGRP-LF is a type II membrane protein composed of 369 amino-acid residues, with a very short amino-terminal cytoplasmic domain (residues 1–23) followed by a transmembrane segment (residues 24–46). The extracellular part of the protein is composed of two PGRP domains, LFz and LFw. The LFz domain (residues 52–225; Fig 1) was expressed in Drosophila S2 cells and its crystal structure was determined at 1.72 Å resolution. The crystals contain two copies of the protein in the asymmetrical unit, designated as chain A and chain B. LFz comprises a central β-sheet composed of six β-strands surrounded by three α-helices and two 310 turns (Fig 2A). LFz contains one disulphide bridge (Cys94–100), that tethers the helix α1 to the loop β1–β2.

Figure 1.

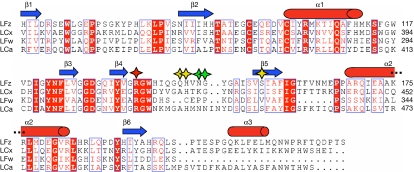

Sequence alignment of the LFz, LFw, LCx and LCa peptidoglycan-recognition protein domains. Secondary structure elements are indicated above the sequences as blue arrows and red cylinders. Conserved residues are boxed and strictly conserved residues are shown in white with a red background. The conserved arginine residue determinant for the DAP-type specificity is marked with a red star. Important residues that are responsible for the lack of the binding of LFz and LFw to PGN are marked with yellow and green stars, respectively. DAP, diaminopimelic acid; PGN, peptidoglycan; PGRP, peptidoglycan-recognition protein.

Figure 2.

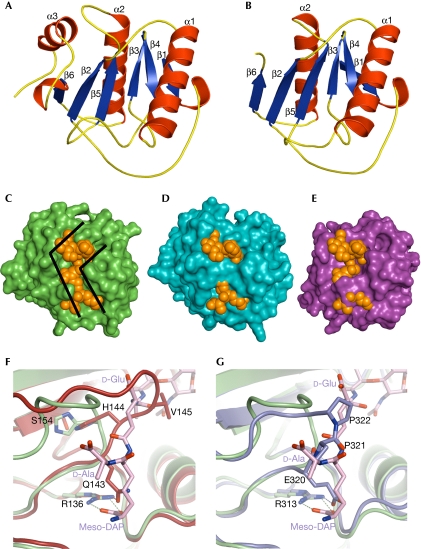

Structures of LFz and LFw. (A,B) LFz and LFw structures are shown in ribbon representation, with the strands coloured in blue and the helices coloured in red. The secondary structure elements are labelled. LFw is shorter than LFz and lacks the α3 helix. (C–E) Molecular surfaces of LCx, LFz and LFw are shown in green, blue and purple, respectively. The TCT is represented in space-filling mode and shown in orange. The position of the TCT at the molecular surfaces of LFz and LFw was given by the superimposition of the structure of LCx in complex with TCT on that of LFz and LFw, respectively. The L-shape crevice present at the surface of LCx (C) is disrupted in LFz (D) and LFw (E), preventing the binding of TCT. (F) The structures of LFz and LCx in complex with TCT are superimposed and shown in red and green, respectively. The TCT bound to LCx is represented as sticks coloured according to atom type (carbon, pink; nitrogen, blue; oxygen, red). The interaction between H 144 and S 154 pushes away the β4–β5 loop of LFz, which takes the position occupied by the second amino acid (D-Glu) of the TCT stem peptide. Q 143 binds to the crucial arginine R 136 with hydrogen bonds, preventing the interaction with meso-DAP of the TCT. (G) The structures of LFw and LCx in complex with TCT are superimposed and shown in purple and green, respectively. Two proline residues (P 321 and P 322) of the β4–β5 loop in LFw take the place of the second and forth amino acid (D-Glu and D-Ala) of the TCT stem peptide. E 320 of LFw has the same role as Q 143 of LFz. DAP, diaminopimelic acid; TCT, tracheal cytotoxin.

The LFw domain (residues 230–369; Fig 1) of PGRP-LF was produced in E. coli and its crystal structure was determined at 1.9 Å resolution. As for LFz, the final refined model contains two molecules in the crystallographic asymmetrical unit designated as chain A and chain B. The structure of the LFw domain is similar to that of LFz except for the carboxy-terminal part (Fig 2B). Although LFw has most of the classical structural features of the family—such as the central β-sheet and the conserved disulphide bridge (Cys271–277)—it contains only two α-helices and one 310 turn, making it the shortest Drosophila PGRP domain.

LFz and LFw have a modified PGN-binding groove

All previously reported PGRP structures, with the exception of PGRP-LCa, contain a conserved L-shaped cleft that forms the PGN-binding pocket. The bottom of this groove is formed by the central β-sheet, whereas the walls are constituted on one side by the β6–α3 and β4–β5 loops and on the other by the C-terminal part of the α1 helix and the beginning of the α1–β3 loop. Residue insertions in the β6–α3 and β4–β5 loops disrupt the PGN-binding site in PGRP-LCa, explaining its inability to bind to PGN. To estimate whether PGRP-LF is a PGN-binding protein, the crystal structure of PGRP-LCx (Chang et al, 2006) in complex with TCT was superimposed on LFz and LFw structures. These superimpositions indicate that LFz structure is similar to that of LCx as 135 Cα of the 165 Cα (82%) of the model have equivalent positions in both molecules, with the distance between the superimposed Cα atoms being <1 Å. However, a structural difference distinguishes LFz from LCx: the β4–β5 loop adopts a different conformation in LFz, leading to complete obstruction of the putative PGN-binding site (Fig 2C,D). We believe that the orientation of the LFz β4–β5 loop is not due to a packing effect, as no symmetry-related molecule is found nearby. Moreover, an extensive network of hydrogen bonds maintains the position of the β4–β5 loop. The main consequence of this conformational change is that the LFz β4–β5 loop protrudes into the crevice, taking the position that the D-Glu of the TCT stem peptide occupies in an LCx–TCT interaction (Fig 2F). In addition, Q143OE1 forms a hydrogen bond with R136NH2, and blocks access to this arginine, which engages in an electrostatic interaction with TCT that is essential for an efficient LCx–TCT interaction (Chang et al, 2006; Lim et al, 2006).

For LFw, 95 out of 135 residues have equivalent positions in LCx (distance between the superimposed Cα atoms: <1 Å), giving a structural similarity of 70%. The main differences between the two domains are in the C-terminal part of the molecule. The β5–α2 loop (334–338) is six residues shorter in LFw than in other PGRP domains. As a consequence, the α2 helix and β6 strand (residues 339–363) are slightly displaced, accounting for many of the non-equivalent residues. Differences also occur in the crucial β4–β5 loop, which is two residues shorter than in LCx (Fig 1). The shortening of the domain together with the presence of two contiguous proline residues (Pro 321 and Pro 322) explains why the β4–β5 loop adopts a unique folding conformation in LFw (Fig 2E,G). As a consequence, the two proline residues located at the tip of the loop occupy a position that the D-Glu of the TCT stem peptide would fill in a functional LCx–TCT interaction. In addition, Glu 320 forms a hydrogen bond with Arg 313 and has a similar role to Gln 143 in LFz.

Altogether, the analyses of LFw and LFz crystal structures indicate that neither of the PGRP domains of PGRP-LF is able to directly interact with PGN or its derivatives.

PGRP domains of PGRP-LF do not bind to DAP-type PGNs

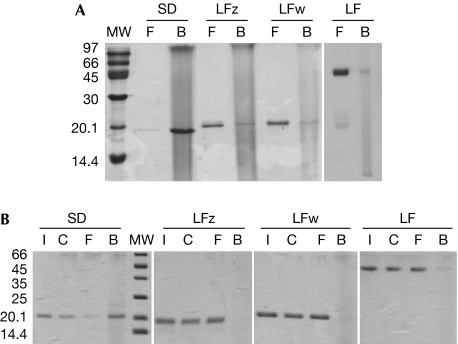

To confirm our structural data, we tested the ability of the LFz and LFw domains to bind to DAP-type PGN, by using pull-down experiments with insoluble PGNs isolated from the Gram-negative bacteria, Escherichia coli. Our results demonstrate that neither LFz or LFw domains are PGN-binding domains. By using the same assay, it was shown that the DAP-type PGN-binding protein PGRP-SD (Leone et al, 2008) binds to PGN (Fig 3A). Pull-down assays performed with the full-length ectodomain comprising the two PGRP domains, to investigate a potential cooperative effect, yielded identical results (Fig 3A). As the pull-down method does not analyse complexes at equilibrium, fast-dissociating complexes might not be detected by this method. PGN binding to PGRP-LF domains was therefore evaluated by using the hold-up technique. Again, we showed that LFz, LFw and the full-length ectodomain are unable to bind to PGN, even transiently (Fig 3B). The biochemical results presented above confirm the hypothesis made as a result of the structural analyses, and allow us to conclude that PGRP-LF does not interact directly with PGN. Pull-down assays were performed with proteins for which the V5-His tag was removed by limited proteolysis. V5-His-tagged proteins gave different results (supplementary Fig S1 online), that resemble those obtained by Persson et al (2007). This might suggest interferences between the tag and the PGN in the pull-down assay.

Figure 3.

Binding experiments with insoluble peptidoglycan from Escherichia coli. (A) The binding of LFz, LFw and LF (full-length ectodomain) was assayed by pull-down assay with insoluble PGN from E. coli. Recombinant SD protein was used as a positive control. The lanes are labelled as follows: MW=molecular weight markers, F=free (not bound) fraction present in the supernatant, B=bound fraction in the pellet. LFz, LFw and LF are found in the unbound fraction in contrast to the positive control protein (SD). Pull-down assays were performed more than five times. (B) Hold-up assays were performed to analyse the binding of LFz, LFw and LF (full-length ectodomain) to insoluble PGN. Recombinant SD protein was used as positive control. The lanes are labelled as follows: MW=molecular weight markers, I=input, C=control with no PGN in the well, F=free (unbound) fraction, B=bound fraction. LFz, LFw and full-length LF do not bind to PGN, in contrast to the positive control protein (SD). Holdup assays were performed twice. PGN, peptidoglycan.

PGRP-LF ectodomain interacts with PGRP-LC ectodomains

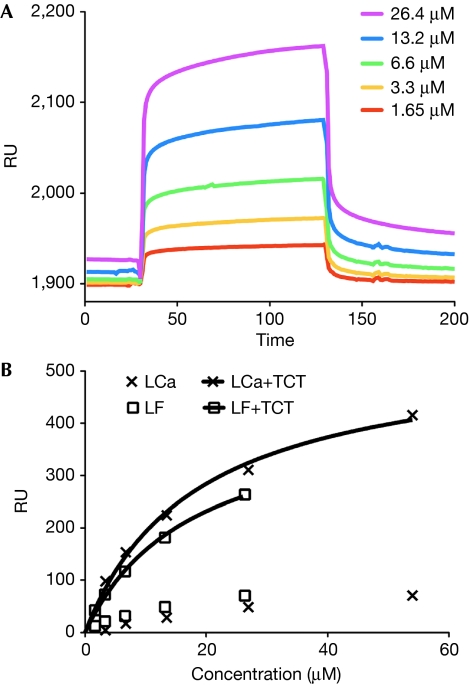

If PGRP-LF does not bind to PGN, how does it interfere with PGRP-LC signalling? An alternative hypothesis is that it interacts with the signalling receptor itself, instead of the ligand. To identify a putative PGRP-LF–PGRP-LC interaction, we used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) imaging, with LCx immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip. The binding properties of LF and LCa domains were evaluated in the presence or absence of TCT. We demonstrate that, in the absence of TCT, LF displays the same weak affinity for LCx as LCa does for LCx. The same series of concentrations of LCa with a constant amount of TCT resulted in an increased response (approximately sevenfold). The affinity constant, Kd, of LCa–LCx binding was 18.3±8.3 μM (95% confidence interval). When the same experiment was performed with LF in the presence of TCT, the responses were similar to those measured with LCa, with a calculated Kd of 17.6±6.1 μM (Fig 4). Injection of TCT alone or the Lys-type PGN-binding protein PGRP-SA (20 μM), in the presence and absence of TCT, gave negligible responses (10–20 refractive units). In conclusion, SPR imaging studies confirm that TCT strongly enhances interactions with LCx, and show that LF interacts with LCx in a similar way to LCa, in the absence and presence of TCT.

Figure 4.

Interaction between PGRP-LCx, PGRP-LCa and PGRP-LF measured by surface plasmon resonance (Biacore). (A) Sensorgrams representing the concentration-dependent binding of the ectodomain of PGRP-LF, in the presence of a constant amount of TCT, with the PGRP domain of PGRP-LCx immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip. The contact time (association) was 100 s and the dissociation time was 200 s, with no regeneration step. (B) Non-linear affinity analysis of the binding of PGRP-LCa and PGRP-LF, in the absence of TCT or in the presence of a constant amount of TCT. The concentration ranges were 2.38–54 μM and 1.65–26.4 μM for PGRP-LCa and PGRP-LF, respectively. PGRP, peptidoglycan-recognition protein; RU, refractive units; TCT, tracheal cytotoxin.

Discussion

PGRP-LC, a member of the membrane PGRP family, is required for activation of the Imd pathway in response to Gram-negative bacterial infections. Several studies have shown that overexpression of full-length PGRP-LCa or PGRP-LCx in the absence of PGN is sufficient to trigger downstream signalling, both in vitro (S2 cells) and in vivo (flies). Moreover, Kaneko et al (2004) have shown that all three PGRP-LC isoforms can homo- or hetero-oligomerize in vitro in the absence of PGN. This suggests that in vivo mechanisms prevent spontaneous dimerization of PGRP-LC molecules. Here, we propose a model in which the transmembrane protein PGRP-LF functions to prevent spontaneous Imd pathway activation by forming non-signalling heterodimers with PGRP-LC isoforms. By solving the crystal structures of both PGRP-LF PGRP domains, we show that their putative PGN-binding groove is unable to accommodate a functional interaction with TCT. This was confirmed by pull-down and hold-up experiments. PGRP-LF, together with PGRP-LCa, is the second Drosophila PGRP-domain-containing protein that has been shown to be unable to bind to PGN. The results obtained by SPR show that LF interacts with LCx in the absence of TCT at a level comparable to the interaction between LCx and LCa. However, in addition to confirming the previously reported interaction between LCx and LCa in the presence of TCT, SPR data show that LF also strongly interacts with LCx in the presence of TCT. This unexpected result reflects the high level of structural homology between the PGRP domains of PGRP-LF and PGRP-LC. PGRP-LF could therefore be considered to be a competitor of PGRP-LCa, in the absence or presence of TCT. This suggests a mechanism for Imd downregulation on the basis of the competition between LCa and LF for the binding to LCx. Consequently, it can be inferred that the presence of LF at the cell surface would reduce the probability of forming unwanted signalling LC dimers in the absence of TCT, and would thus contribute to the maintenance of a low background level. This is consistent with the fact that removing PGRP-LF in vivo is sufficient to trigger Imd signalling. The presence of TCT would increase not only the number of LF/TCT/LCx complexes, but also the number of signalling LCa/TCT/LCx complexes, leading to the activation of the pathway. Finally, on the basis of our model, one prediction would be that increasing the number of LF molecules at the cell surface will decrease the number of signalling LC dimers and, in turn, the intensity of the response. This has been reported in flies in which PGRP-LF has been overexpressed. The SPR studies have been performed with TCT. Further studies should be designed to investigate the interaction of PGRP-LF with PGRP-LC isoforms in the presence of polymeric PGN.

Methods

Crystallization and structure determination. LFz and LFw were overexpressed in Drosophila S2 cells and in E. coli, respectively, and purified with affinity chromatography followed by gel filtration. The V5-His tag of LFz was removed by limited proteolysis. Crystallization was performed at 20°C, by hanging-drop vapor-diffusion. After flash-freezing at 100 K in liquid nitrogen, data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Both structures were solved by molecular replacement with PHENIX (Adams et al, 2002), using the structure of PGRP-LCx and PGRP-LCa as starting models (PDB code: 2F2 L chain X and chain A). Refinement was performed using PHENIX.REFINE (Adams et al, 2002) and Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004). Structural analysis was performed using the program Turbo-Frodo (Roussel & Cambillau, 1991). Atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org) under the accession codes 2XZ4 and 2XZ8. The crystallographic parameters of the two structures are listed in Table 1. All structure figures were prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org). Further details can be found in the supplementary information online.

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| LFz | LFw | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | ||

| Radiation source | ESRF ID14-2 | ESRF ID14-2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9330 | 0.9330 |

| Spacegroup | P21212 | P6522 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 74.80, 113.44, 37.53 | 82.24, 82.24, 178.62 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 45.17–1.72 (1.81–1.72) | 37.82–1.94 (2.04–1.94) |

| Total observations | 121,143 (14,103) | 108,012 (15,720) |

| Unique reflections | 34,205 (4,806) | 27,070 (3,832) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.6 (96.5) | 99.4 (98.9) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 (2.9) | 4.0 (4.1) |

| Rmerge* | 5.2 (36.1) | 7.8 (39.9) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 15.3 (2.9) | 12.5 (3.8) |

| Refinement and model statistics | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.75–1.72 (1.78–1.72) | 35.61–1.94 (2.01–1.94) |

| Proteins per AU | 2 | 2 |

| Number of reflections used | 34,162 (3,261) | 27,026 (2,625) |

| Rwork (%)‡/Rfree (%)§ | 16.36/20.14 (21.53/23.71) | 17.4/21.0 (19.9/22.1) |

| Average B-values (Å2) | ||

| All atoms | 27.1 | 30.6 |

| Protein chain A atoms | 22.7 | 28.5 |

| Protein chain B atoms | 29.4 | 30.4 |

| Cu2+ atom | 34.1 | |

| Na+ atom | 37.0 | |

| Ethylene glycol atoms | 44.3 | |

| PEG300 atoms | 39.3 | 53.7 |

| Water atoms | 37.6 | 39.8 |

| Root mean square deviation from ideality | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.084 | 1.015 |

| Dihedral angles (°) | 13.708 | 16.086 |

| Ramachandran analysis (% of residues) | ||

| Favoured/allowed/outliers | 97.5/2.5/0.0 | 97.0/2.3/0.7 |

| Number of atoms | ||

| Protein chain A | 1,319 | 1,042 |

| Protein chain B | 1,295 | 1,032 |

| Cu2+ | 1 | |

| Na+ | 1 | |

| Ethylene glycol | 20 | |

| PEG300 | 14 | 34 |

| Water | 228 | 181 |

| *Rmerge=∑h∑i∣Ih,I–〈I〉h∣/∑h∑i Ih,i where 〈I〉h is the mean intensity of the symmetry-equivalent reflections. | ||

| ‡Rwork=∑h∣∣Fo∣–∣Fc∣∣/∑h∣Fo∣ where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively, for reflection h. | ||

| §Rfree is the R-value for a subset of 5% of the reflection data, which were not included in the crystallographic refinement. | ||

PGN-binding assays. As well as the standard pull-down assay, an equilibrium-binding assay was designed following the hold-up technique presented by Charbonnier et al (2006). The hold-up assay is based on the principle of comparative retention. To have reproducible results and treat the samples and controls simultaneously, we automated this assay on a Tecan robot, using a protocol modified from Vincentelli et al (2005). Further details can be found in the supplementary information online.

SPR analysis. Interactions between PGRP-LCx and PGRP-LCa or PGRP-LF, with and without TCT were measured using a Biacore X100. SPR measurements were performed using a Biacore X100 optical biosensor with a research grade CM5 sensor chip (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). PGRP-LCx was immobilized using standard amine-coupling chemistry according to the manufacturer's instructions (Biacore Inc.). The binding experiments were performed by injecting increasing concentrations of proteins. Further descriptions are given in the supplementary information online.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility at Grenoble, France and the beamline ID14 staff in particular, for their assistance. Highly purified TCT was obtained from Dominique Mengin-Lecreulx. We thank Annemarie Lellouch for critical reading. This work was supported by an Action Thematique et Incitative sur Programme (ATIP) programme of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (2005–2010, to A.R.) and by a grant from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche-Microbiologie, Immunologie et Maladies Emergeantes (ANR-MIME, to A.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC (2002) PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58: 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff V, Vignal C, Duvic B, Boneca IG, Hoffmann JA, Royet J (2006) Downregulation of the Drosophila immune response by peptidoglycan-recognition proteins SC1 and SC2. PLoS Pathog 2: e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CI, Chelliah Y, Borek D, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Deisenhofer J (2006) Structure of tracheal cytotoxin in complex with a heterodimeric pattern-recognition receptor. Science 311: 1761–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier S, Zanier K, Masson M, Trave G (2006) Capturing protein–protein complexes at equilibrium: the holdup comparative chromatographic retention assay. Protein Expr Purif 50: 89–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe KM, Lee H, Anderson KV (2005) Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition protein LC (PGRP-LC) acts as a signal-transducing innate immune receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1122–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe KM, Werner T, Stoven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV (2002) Requirement for a peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) in Relish activation and antibacterial immune responses in Drosophila. Science 296: 359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D, Imler JL, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA (2007) The Drosophila systemic immune response: sensing and signalling during bacterial and fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 862–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottar M, Gobert V, Michel T, Belvin M, Duyk G, Hoffmann JA, Ferrandon D, Royet J (2002) The Drosophila immune response against Gram-negative bacteria is mediated by a peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature 416: 640–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Goldman WE, Mellroth P, Steiner H, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Harley W, Fox A, Golenbock D, Silverman N (2004) Monomeric and polymeric gram-negative peptidoglycan but not purified LPS stimulate the Drosophila IMD pathway. Immunity 20: 637–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA (1996) The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 86: 973–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone P, Bischoff V, Kellenberger C, Hetru C, Royet J, Roussel A (2008) Crystal structure of Drosophila PGRP-SD suggests binding to DAP-type but not lysine-type peptidoglycan. Mol Immunol 45: 2521–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leulier F, Parquet C, Pili-Floury S, Ryu JH, Caroff M, Lee WJ, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Lemaitre B (2003) The Drosophila immune system detects bacteria through specific peptidoglycan recognition. Nat Immunol 4: 478–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhocine N, Ribeiro PS, Buchon N, Wepf A, Wilson R, Tenev T, Lemaitre B, Gstaiger M, Meier P, Leulier F (2008) PIMS modulates immune tolerance by negatively regulating Drosophila innate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe 4: 147–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Kim MS, Kim HE, Yano T, Oshima Y, Aggarwal K, Goldman WE, Silverman N, Kurata S, Oh BH (2006) Structural basis for preferential recognition of diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan by a subset of peptidoglycan recognition proteins. J Biol Chem 281: 8286–8295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet F, Bischoff V, Vignal C, Hoffmann J, Royet J (2008) The Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition protein PGRP-LF blocks PGRP-LC and IMD/JNK pathway activation. Cell Host Microbe 3: 293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellroth P, Karlsson J, Hakansson J, Schultz N, Goldman WE, Steiner H (2005) Ligand-induced dimerization of Drosophila peptidoglycan recognition proteins in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 6455–6460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel T, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Royet J (2001) Drosophila Toll is activated by Gram-positive bacteria through a circulating peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature 414: 756–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson C, Oldenvi S, Steiner H (2007) Peptidoglycan recognition protein LF: a negative regulator of Drosophila immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 37: 1309–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramet M, Manfruelli P, Pearson A, Mathey-Prevot B, Ezekowitz RA (2002) Functional genomic analysis of phagocytosis and identification of a Drosophila receptor for E. coli. Nature 416: 644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel A, Cambillau C (1991) Turbo-Frodo. In Silicon Graphics Geometry Partners Directory, p 86. Mountain View, CA, USA: Silicon Graphics [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Kim SH, Lee HY, Bai JY, Nam YD, Bae JW, Lee DG, Shin SC, Ha EM, Lee WJ (2008) Innate immune homeostasis by the homeobox gene caudal and commensal-gut mutualism in Drosophila. Science 319: 777–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincentelli R, Canaan S, Offant J, Cambillau C, Bignon C (2005) Automated expression and solubility screening of His-tagged proteins in 96-well format. Anal Biochem 346: 77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Remy A, Herve M, Poidevin M, Pili-Floury S, Kim MS, Blanot D, Oh BH, Ueda R, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Lemaitre B (2006) The Drosophila amidase PGRP-LB modulates the immune response to bacterial infection. Immunity 24: 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.